In this issue of Blood, Chihara et al1 report low real-world utilization, but encouraging efficacy, of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy as third- or later-line therapy for older adults with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The authors interrogated the Medicare Fee-for-Service claims database to evaluate outcomes and health care utilization costs associated with CAR T-cell therapy (CAR-T) with a specific focus on older adult (aged ≥65 years) patients with DLBCL treated over a 2-year period (2018-2020).

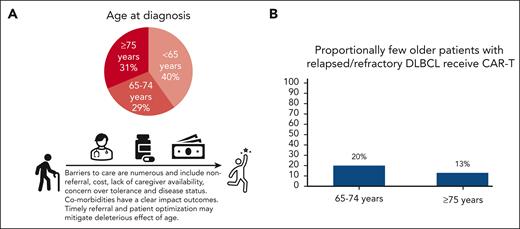

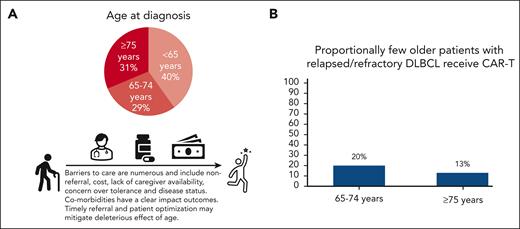

DLBCL predominantly affects older adults, with the majority of patients aged over 60 years and one-third ≥75 years at diagnosis2 (see figure). Historically, outcomes were poor for patients of any age with disease refractory to, or progressive after, frontline therapy. CD19-directed autologous CAR-T has revolutionized care for those patients. Despite improved outcomes with CAR-T, most recently illustrated by randomized trials in the second-line setting,3,4 multifactorial barriers limit uptake in the older adult. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that older patients are more likely to be under- rather than overtreated, and nonreferral is the greatest barrier to specialized treatment for hematologic malignancies.5 Chronological age continues to influence oncologists’ decision making,6 with concerns including uncertainty regarding eligibility, the presence of comorbidities, impaired physical or cognitive function, caregiver support, distance to a specialized treatment center, and potential societal and patient-level costs.5 Although these concerns are valid, they can also result in withholding or attenuation of curative regimens. Given the context, multiple illuminating features of this report warrant attention.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a disease of older adults, yet CAR-T is underutilized in these patients. (A) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program12 data illustrating age breakdown at diagnosis, highlighting that DLBCL predominantly affects older adults, with the majority (60%) aged >65 years and almost one-third aged ≥75 years. (B) Chihara et al report low real-world utilization of CAR-T in third-line or later therapy: 20% of patients aged 65 to 75 years, and 13% of those aged ≥75 years. Improving patient optimization, product selection, and toxicity management will likely lead to better outcomes for older adults and potentially reduce costs.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is a disease of older adults, yet CAR-T is underutilized in these patients. (A) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program12 data illustrating age breakdown at diagnosis, highlighting that DLBCL predominantly affects older adults, with the majority (60%) aged >65 years and almost one-third aged ≥75 years. (B) Chihara et al report low real-world utilization of CAR-T in third-line or later therapy: 20% of patients aged 65 to 75 years, and 13% of those aged ≥75 years. Improving patient optimization, product selection, and toxicity management will likely lead to better outcomes for older adults and potentially reduce costs.

First, of patients with DLBCL identified as needing third- or later-line therapy, only 20% of those aged 65 to 75 years and 13% of those aged ≥75 years received CAR-T. The decreasing numbers for patients aged ≥75 years suggest age alone may be playing into this dismal penetrance, although absence of comparable data in adult patients aged <65 years precludes isolation of age as a variable. Second, the work confirms a high incidence of comorbidities in this age group by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), with higher comorbidity burden (CCI ≥ 5) significantly impacting event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS). Although pivotal trials of CAR-T generally excluded those with moderate to severe comorbidities, real-world evidence has also demonstrated that comorbidities associate with worse efficacy.7 Third, the authors report OS outcomes after CAR-T therapy are similar across age groups in this population.

These results are generally consistent with published data: older patients who receive CAR-T have similar survival outcomes compared with younger patients. Interestingly, the authors report inferior EFS with higher age, whereas real-world registry data with axicabtagene ciloleucel suggest trends toward improved efficacy in older patients.8 Given its more favorable toxicity profile, tisagenlecleucel may be preferred in older patients with comorbidities; however, data suggest tisagenlecleucel has inferior efficacy compared with axicabtagene ciloleucel.9 Information on the specific CAR-T product was not available in the data set analyzed by Chihara et al, potentially confounding the EFS results stratified by age. Finally, Chihara et al report on Medicare claims generated for billing purposes in patients receiving CAR-T. It is noteworthy that the per patient estimates (mean, $352 572) were less than published elsewhere and were numerically lower in the ≥75 years age category despite the expectation for a higher incidence of severe toxicity and prolonged length of stay. Although outpatient CAR-T administration may result in more complete Medicare reimbursement of the CAR-T product, inpatient administration is more common, and Medicare reimbursement of hospitalization is based on a bundle payment by the diagnosis-related group, which is likely lower than the combined price tag of the CAR-T product plus utilization costs. CAR-T products with safety profiles favorable to treatment in the outpatient setting and toxicity management and prophylaxis strategies that decrease rates of severe toxicities will likely reduce health care utilization costs. This may further address a key barrier to access in the older adult, in which cost of therapy can be a major consideration.

Beyond the limitations outlined above, additional deficits in the data set must be considered when interpreting these results. Key prognostic variables illuminated in trials (eg, tumor size) or from prior real-world studies (eg, performance status) could not be corrected for and, therefore, may have confounded the impact of age. In addition, the incidence and severity of known CAR-T toxicities such as cytokine release syndrome, neurological events, and prolonged cytopenias were not available. As these features have been described as increased in severity in older adults, this also could have influenced outcomes. Furthermore, no information on the impact on quality of life (QoL) was available in this analysis, which understandably plays a critical role in health care decision making for older adults. Real-world data in this space is limited but suggest that after an initial decline during the time of hospitalization, older adults treated with CAR-T can anticipate an equivalent improvement above baseline in their QoL reported 3 months postinfusion, similar to their younger counterparts.10 Lastly, as outlined above, the cost of the CAR-T product itself is likely not fully reflected in this data set, and, therefore, it probably underestimates the true per-patient costs to the health care system.

A comprehensive approach to the assessment of older adults being considered for cellular therapies has been adopted by several large centers, with the goal of informing both patient and product selection.11 As a result, selected older patients with medically optimized comorbidities can anticipate potential benefit from this approach, equivalent to their younger counterparts.3,8 Early referral and assessment is key, recognizing that timely collection and controlling disease burden are just as important as optimizing comorbidities and performance status. Novel approaches to predict CAR-T outcomes are emerging to account for assessment of biological (rather than chronological) age, immune-nutritional status, and body composition. Development in this space will likely lead to further improvements in patient selection and determining those most suited to outpatient administration of CAR-T or at greatest need of additional interventions like prophylaxis to limit toxicities.

Overall, these results add to the growing literature that similar outcomes can be achieved using CAR-T to treat optimized older adults. As we continue to refine risk management, expand the pool of eligible patients, and address the unique considerations of geriatric oncology, complex immunotherapies hold great promise for transforming the landscape of lymphoma treatment in this patient population, which in fact comprise the majority treated in a real-world setting. With ongoing efforts in this space, we envision a future in which the potential for cure with an improved quality of life is available for many more older adults with relapsed lymphoma.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.L.F. reports honoraria/consulting fees from BMS, Seattle Genetics, Celgene, AbbVie, Sanofi, Incyte, Amgen, ONK Therapeutics, and Janssen and research funding from BMS, Janssen, and Roche/Genentech. F.L.L. reports a scientific advisory role/consulting fees for Allogene, Amgen, bluebird bio, BMS/Celgene, Calibr, Caribou, Cellular Biomedicine Group, Cowen, Daiichi Sankyo, EcoR1, Emerging Therapy Solutions, GammaDelta Therapeutics, Gerson Lehrman Group, Iovance, Kite Pharma, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Novartis, Sana, Takeda, Wugen, and Umoja; research funding from Kite Pharma (institutional), Allogene (institutional), Novartis (institutional), bluebird bio (institutional), CERo Therapeutics (institutional), and BMS (institutional); patents, royalties, and other intellectual property, including several patents held by the institution in his name (unlicensed) in the field of cellular immunotherapy; and education or editorial activity for Aptitude Health, ASH, BioPharma Communications CARE Education, Clinical Care Options Oncology, Imedex, and Society of Immunotherapy of Cancer.