Abstract

Manufacturing capacity and institutional infrastructure to deliver chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies (CAR-T) are pressured to keep pace with the growing number of approved products and expanding eligible patient population for this potentially life-saving therapy. Consequently, many cell therapy programs must make difficult decisions about which patient should get the next available treatment slot. This situation requires an ethical framework to ensure fair and equitable decision-making. In this perspective, we discuss the application of Accountability for Reasonableness (A4R), a priority-setting framework grounded in procedural justice, to the problem of limited CAR-T slots at our institution. We formed a multidisciplinary working group spanning several hematological malignancies. Through multiple rounds of partner engagement, we used A4R guiding principles to identify 4 main criteria to prioritize patients for CAR-T: medical benefit, safety/risk of complications, psychosocial factors, and medical urgency. Associated measures/tools and an implementation process were developed. We discuss further how ethical principles of fairness and equity demand a consistent approach within health systems that does not disadvantage medically underserved or underrepresented populations and supports overcoming barriers to care. In our commitment to transparency and collaboration, we make our tools available to others, ideally to be used to engage in their own A4R process, adapting the tools to their unique environments. Our hope is that our preliminary work will support the advancement of further study in this area globally, aiming for justice in resource allocation for all potential CAR-T candidates, wherever they may seek care.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) is a breakthrough immunotherapy for the treatment of advanced hematological malignancies1 that is expanding into solid tumors and nonmalignant disease. It is highly active therapy with potential to cure or prolong life in patients with heavily pretreated, refractory disease who would otherwise have limited survival. However, CAR-T is complex, resource intensive, and expensive. Currently, it is performed only at specialized cell therapy referral centers by trained health care providers. In addition, CAR-T has significant risks of severe and possibly fatal complications, requiring in-depth counseling, commitment, and understanding by patients and their families.

CAR-T faces significant barriers to its widespread use, resulting in patient access challenges and the need for patient prioritization to limited treatment slots.2 Critical factors that create such barriers include complex logistics, manufacturing limitations, toxicity concerns, and financial burden.3 Patient populations marginalized by socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, insurance status, and geography (ie, proximity to specialized treatment centers), among others, disproportionately face barriers to CAR-T.4,5 In addition, the requirement for caregiver support, sufficient understanding, and willingness to commit/comply with the complexities of the CAR-T process may limit access for some patients.6 Others may experience financial “toxicity,” where lack of insurance coverage, loss of wages, and out-of-pocket transportation and lodging costs create overwhelming barriers.6,7 Although challenges to accessing this therapy are significant and exist at multiple levels of health care delivery, our ethics initiative focused on the point-of-care delivery at our institution to ensure that patients, once they have been referred to our program, are fairly prioritized for accessing the next available CAR-T slot.

September 2018 marked the regulatory approval of the first CAR-T in Canada for commercial use (Novartis product; tisagenlecleucel), subsequently followed by the approval of a second CAR-T product in February 2019 (Gilead product; axicabtagene ciloleucel). Our center, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM), was then 1 of only 3 hospitals certified to provide CAR-T services in a country of 37 million people, with each institution initially allotted only 1 manufacturing slot per month. There was, and continues to be, no commercial manufacturing site in Canada. Patient waiting lists were agonizingly long and distressing, especially given the relentless pace of disease progression typical of a CAR-T candidate. Although manufacturing capacity for these early CAR-T products has since improved, the introduction of newer CAR-T product approvals with expanding indications, such as multiple myeloma, has once again seen a resurgence of long waiting lists for manufacturing slots. However, even with improved manufacturing capacity, waiting the 4- to 6-week turnaround time from apheresis to final CAR-T cell product manufacture can be an insurmountable hurdle for patients with aggressive disease. At PM, one-third of patients who begin the CAR-T process are unable to complete treatment, primarily because of disease progression or death.8 Bed constraints (notably observed during the bed pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic), nursing shortages (enhanced by the post–COVID-19 burnout exodus), and funding restrictions (a heightened hazard in a publicly funded health care system, such as Canada’s) contribute to delays in providing timely treatment. In this scenario, it is mandatory to prioritize patients for CAR-T, and this unenviable task falls on the shoulders of the health care team. Patient prioritization is complex as it must consider not only the number of treatment spots, but also the clinician’s estimation, often subjective, of medical benefit, risk, and prognosis.

Before our ethical prioritization initiative, allocation of available CAR-T slots was collectively performed through deliberation on an ad hoc basis by a multidisciplinary oncology team, the Cell Therapy Review Committee. Decisions were primarily based on perceived medical need and time on wait list. Heated discussions about whose patient should jump the queue were commonplace, with prioritization largely influenced not by evidence or judicious consideration, but by the vigor of patient advocacy (ie, the “squeaky wheel”). Concern was appropriately raised that this process lacked an ethics-based prioritization framework, thereby risking procedural injustice and inequitable patient access. It was clear that we needed a fair and transparent process for CAR-T patient prioritization in which decision-making uses common language, principles, and criteria.

A theoretical framework

Justice concerns are primarily rooted in distributive justice, which broadly refers to the fair sharing of benefits and burdens among individuals.9 However, for fair allocation of health care resources, there is often moral disagreement, and it can be difficult to reach consensus. When distributive justice concerns are unresolvable, reasonable and fair-minded people “must retreat to a process all can agree is a fair way to resolve disputes.”10(p10) The Accountability for Reasonableness (A4R) approach was hence created, offering a practical decision-making framework for priority setting in various health care contexts. Applying A4R, relevant parties seek agreement on how decisions are made (ie, procedural justice) to ensure the fairness of individual decisions or outcomes (ie, distributive justice).11 A4R has been used extensively in other health care contexts where issues concerning fair resource allocation exist,12,13 such as, most recently, vaccine allocation during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus pandemic.14

A4R provides a framework to support procedural justice, or fair process, based on 5 conditions: relevance, empowerment, revision, publicity, and enforcement (Table 1).11,15 The A4R approach can be operationalized by following a publicly available checklist developed by the University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics that guides parties through the prioritization process.16

The process: applying A4R

Identifying relevant parties and scope of our initiative

Our first step was to establish relevant principles or criteria that should be considered when making decisions about priority resource allocation. To participate in identifying these criteria, relevant partners were solicited to participate in a working group through a call for volunteers from the multidisciplinary Cell Therapy team, including those in research and standard-of-care domains, hematological and solid tumor disease groups, leaders and learners, patients, and others holding clinical, operational, quality, or bioethics roles in the CAR-T process (n = 34). Relevant partners were identified as those who would influence or be impacted by decision-making. Participant engagement rules were clearly outlined to support empowerment, whereby attempts to minimize power differences in decision-making would be made. Partners were asked to disregard titles or perceived power within the organization and to recognize that all have an equal and valid voice. This environment was enabled by having a bioethicist, who is trained in mediating values-conflict within unequal power relations, facilitate the meetings. Patients were key partners and engaged in both the working group and in a separate focus group. The focus group consisted only of patient partners and was led by the bioethicist to facilitate open dialogue in a trusting space removed from medical hierarchy.

For the first task of the working group, and further applying the relevance condition of A4R, the group identified the scope of the ethics initiative to be the establishment of a process for fair allocation of scarce CAR-T slots. Although it was recognized that patients could gain access to CAR-T through clinical trials, the rigidity and intricacies of individual trial eligibility were believed to distract from the primary intent of the project and, therefore, the group decided to focus the scope on standard-of-care CAR-T. It was recognized that a prioritization process could be generalizable across many centers, all constrained by the same CAR-T restrictions. However, because resources and operational policies vary significantly between institutions, it was agreed to focus on our institution alone to start, with intent to share learnings with other sites and partners (eg, specialized cell therapy centers and provincial funders) in the future.

Identifying relevant criteria

For the task of identifying criteria relevant to prioritization, the A4R framework was used, using a deliberative and iterative revision process over several consecutive meetings between September 2020 and January 2021. The initiative was led by the authors of this article, the medical director of PM’s clinical cellular therapy program, and the PM senior bioethicist. Acknowledging the publicity condition of A4R and before deliberations about principles and criteria, the group adopted an established definition of consensus in accordance with methodologic criteria for consensus development, whereby >70% agreement would be sought.17 Where it was not possible to reach consensus, the group agreed at least to work toward a common understanding to move forward.

To start, partners were asked to each identify principles or criteria they thought were important to consider when prioritizing patients for limited CAR-T slots. Partners individually wrote their criteria on yellow sticker notes that were applied to the wall for all to review. Each partner was asked to elaborate on his/her rationale for selected criteria, and the group deliberated and debated on the subjective relevance and importance. If, after deliberation, a criterion lost support based on agreed-on consensus, it was discarded. Similar overlapping criteria were grouped together. In a follow-up exercise, the group was presented with an anonymous virtual poll to “up vote” criteria they believed should be highlighted. Prompts for written feedback about the criteria followed each poll item. If disagreement arose within the poll, discussion was invited as to reasons for the disagreement. Patient partners engaged in a separate focus group to provide narrative comment. The poll results and aggregated narrative comments were then presented back to the full working group (inclusive of patients) at a subsequent meeting.

Criteria with the highest support were medical need/acuity (21%), likelihood of benefit (19%), and tolerance/risk of complications (19%). This was followed by adherence to treatment regimen (compliance) (11%), social/caregiver support (8%), impact on other resources (8%), and length of wait (6%). Criteria with the lowest support were first come, first serve (5%) and exhaustion of all other treatment options (2%) (Table 2).

Rich discussion ensued following the identification of several criteria. In terms of medical need/acuity, it was acknowledged by all that CAR-T candidates are often experiencing aggressive disease progression, requiring prompt and expeditious treatment. This rationale for “medical need/acuity” as a priority criterion, however, was questioned by some who expressed concern that even jumping the queue with the timeliest care may not be sufficient to salvage the patient with explosive disease progression.

The criterion of “likelihood of medical benefit” similarly led to productive discussion. Some expressed concern that patient characteristics, such as life-limiting comorbidities, may result in less benefit from CAR-T, although it was acknowledged that differentiating “less benefit” from “increased risk of complications” was nuanced. The group recognized that the rapid expansion of CAR-T into standard of care was based on impressive, albeit preliminary, early-phase data. As a result, evidence-based patient and disease predictors of poor outcomes were not necessarily available to validate criteria selection. For example, inferior outcomes with “refractory disease” were not well established in the literature, and patients were reluctant to accept this as an indicator of lower medical benefit, citing that patients not responsive to previous therapy may still have a chance of good outcomes even if unlikely or remote. The group discussed that in assessing patient factors influencing medical benefit, age alone should not be a criterion given the paucity of data in elderly patients and the risk of being arbitrary (ie, “what distinguishes a 69-year-old patient from a 70-year-old patient”). Furthermore, patient partners questioned how “medical benefit” was judged, citing that the rationale may lack defensibility because it is seen as a hypothetical: “how will we know who benefits”? This raised the question of whether medical benefit abides by the A4R condition of relevant criteria that reasonable people can accept. Using “curability” as a measure of medical benefit was proposed but criticized for giving precedence to patients with lymphoma in whom cure with CAR-T was better established than in patients with myeloma, thereby creating inequity. Using “enhanced quality of life” as a measure of medical benefit was also questioned by patient partners as subjective and not reliably assessed.

Another area of much deliberation involved compliance and social support. Clinicians in the group believed strongly that ability to understand and comply with the complex, multistep CAR-T process was critical to successful outcomes and that any history of noncompliance should be considered relevant. Others suggested that instead of prejudicially labeling a patient as noncompliant, health care providers should more importantly examine the underlying reasons for prior noncompliance and seek to address them. An example was cited of “a single mother with 3 children who does not attend all appointments because of a lack of childcare.” In addition, patients were concerned that the mandatory caregiver requirement could be discriminatory against those living in isolation or lacking immediate family. Patients and other partners believed strongly that establishing a caregiver should be part of the planning process, and not an inclusion/exclusion criterion for CAR-T. The group emphasized the importance of a social worker as part of the initial assessment team to both understand and overcome any psychosocial challenges.

Broad agreement obtained: emergence of 4 themes

Despite areas of contention, broad agreement was ultimately achieved on relevant criteria, and after extensive revision and discussion, 4 themes or categories emerged: medical benefit, safety/risk of complications, psychosocial factors, and medical urgency (Table 3). Although each category of criteria could be influential in determining patient priority, the group believed there was insufficient data to apply relative weights in importance or value, although application in ordered sequence was crucial. For example, it was agreed that determination of medical benefit should be evaluated as the first consideration. If a patient is deemed to have little or no potential for medical benefit from CAR-T, there should be little rationale to proceed further. Medical benefit assessment would require understanding of the disease and associated literature, best performed by disease-specific experts. If any degree of medical benefit was deemed possible, the patient could proceed to next steps. Safety/risk and psychosocial evaluation would follow, using existing tools (eg, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale) and allowing for summative objectives, when possible. Experts in social, financial, emotional, and functional assessments could be engaged in assessing and addressing psychosocial factors.

Last, medical urgency, as defined by factors such as rapid pace of disease progression, refractoriness to prior therapy, and development of serious disease-related complications, was considered critical in prioritizing patients for therapy. However, the group agreed and cautioned that medical urgency does not equate medical benefit, as patients with rapidly expanding disease and short-term deterioration frequently have dismal outcomes, despite all attempts to expedite their treatment course. In the difficult circumstance where 2 similarly ranked patients with rapidly progressing disease are vying for 1 immediate treatment spot, other options, such as deferral to other centers or clinical trials, should be considered. The Cell Therapy Review Committee may more closely examine each patient’s potential for medical benefit (via a greater number of checked variables on the medical benefit assessment form) and assess this against the potential risks. The tenuous risk-benefit balance in a rapidly progressing patient demands frequent and frank discussions with the patient and family, allowing for evolving patient decision-making. With growing awareness of emergent risks (and potential for declining benefit), a rapidly progressing patient may understandably choose not to proceed. If disagreement or uncertainty persists, tie-breaking options may include consideration of length of time on the wait list or a random lottery draw, recognizing from an egalitarian perspective that these may be the fairest ways to prioritize, ceteris paribus.

Development of a 3-step ethical prioritization process

These ratified criteria anchored the final ethical framework for patient prioritization to CAR-T. It was concluded that prioritization is needed at 2 levels: (1) the disease-site level and (2) the Cell Therapy Review Committee level. For the disease site, patients must be prioritized within each participating disease site (ie, lymphoma, myeloma, and leukemia). For the committee, patients must be prioritized across these disease sites. Recognizing the importance of sequencing in the assessment of criteria, the working group developed a 3-step prioritization process (Table 4). Criteria incorporated into each step are listed to remind clinicians during CAR-T evaluation of relevant criteria to consider in prioritization. The checking off of criteria by tickbox acts as clear documentation (publicity) for discussion and dissemination within the circle of care. Notably, criteria are listed in no particular order, criteria are not weighted in importance, and there is deliberately no final score to avoid oversimplifying priority comparison between patients. It is also important to emphasize that the process and measurement tools we developed were to assist in transparent priority decision-making and flag risks to be addressed or optimized. Specifically, they were not meant to be a list of rigid exclusion criteria for CAR-T.

Step 1

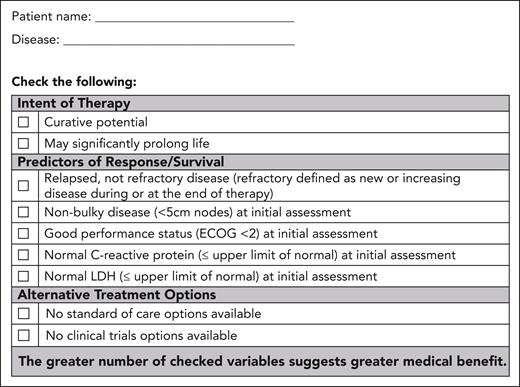

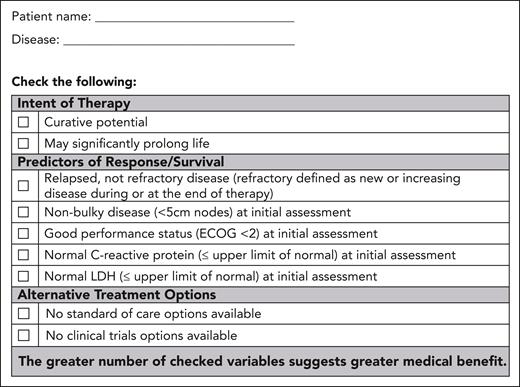

Patients are first assessed for medical benefit by disease site teams, considering the agreed-on criteria and documented on the partner-developed Medical Benefit Assessment Tool A (Figure 1). It is emphasized that criteria indicating any degree of benefit may be adequate to proceed a patient to step 2.

Form A: medical benefit assessment tool. This form enables a standardized assessment of medical benefit and documentation.

Form A: medical benefit assessment tool. This form enables a standardized assessment of medical benefit and documentation.

Step 2

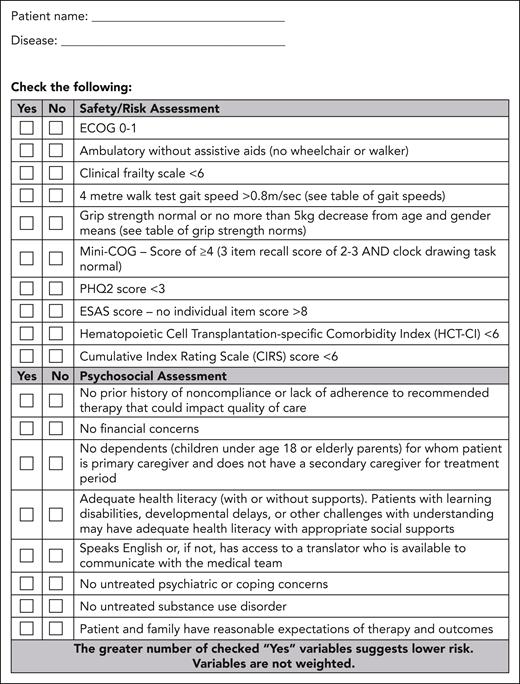

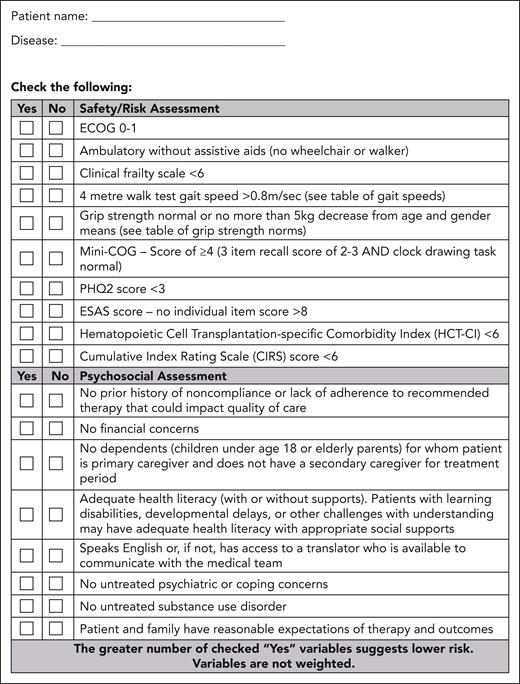

A team, composed of a cell therapy specialist, a cell therapy coordinator, a social worker, a registered nurse, and others as needed (eg, psychiatrist, pharmacist, and organ specialists), performs a standardized assessment to evaluate for functional and psychosocial challenges that may limit optimal CAR-T tolerance. The team will evaluate safety and psychosocial factors using the partner-developed Safety/Risk and Psychosocial Assessment Tool (Figure 2). For example, for the safety/risk assessments, predictive factors for cytokine release syndrome and/or neurotoxicity, as reported in the literature, will be assessed. Caregiver availability will be determined, and any additional supports to enhance caregiver activation will be put in place with assistance from a social worker. It is recognized that predictors of toxicity will vary with disease and product, and change as the CAR-T landscape evolves; therefore, the safety/risk portion of the assessment tool should remain fluid and subject to frequent updates.

Form B: safety/risk and psychosocial assessment tool. This form enables a standardized assessment of safety, psychosocial factors, and documentation. ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; PHQ2, Patient Health Questionnaire-2.

Form B: safety/risk and psychosocial assessment tool. This form enables a standardized assessment of safety, psychosocial factors, and documentation. ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; PHQ2, Patient Health Questionnaire-2.

Step 3

Patients who may gain medical benefit, have reasonable risk of toxicity, and have adequate (or at least optimized) psychosocial support from steps 1 and 2 will proceed to step 3 and be formally discussed as a group at the weekly Cell Therapy Review Committee meetings. At these meetings, the extended Cell Therapy Team, including multiple disease sites, disciplines, and operational and clinical staff, participates in consensus review and prioritization. Although step 3 will give clinicians the voice to advocate for their own patients based on medical urgency, the criteria identified in previous steps and transparently documented on forms A and B will help prevent prejudice toward the squeaky wheel. The employment of a systematic process and documentation is believed to promote procedural justice, aligned with A4R principles.

Conclusion

In a single-payer, universal health care system, such as Canada’s, many challenges to providing timely, efficient CAR-T to needy patients exist. National health systems must provide payment or reimbursement of this expensive therapy using a finite budget across many competing programs. Reliance on public funding for cell therapy infrastructure often means only a few select centers can be supported, given the significant expertise and complexity of resources required for CAR-T service. Inequities in accessing efficient referral to specialized cell therapy centers arise within a system dependent on interprovincial, or even out-of-country, provision of cell therapy care. Indirect and out-of-pocket costs are not covered by government insurance plans in Canada, leaving individual institutions and/or patients responsible to find funding to support treatment. To truly be equitable and reduce access barriers to CAR-T, all of these challenges need to be addressed nationally, in a coordinated approach. However, it is worth emphasizing that the need for ethical allocation of limited CAR-T is independent of a publicly or privately funded health care system. Resource allocation issues arise whenever there is an issue of demand outstripping supply. Restricted health care budgets, coupled with the high cost of CAR-T, contribute to the problem, but as mentioned previously, other factors, such as manufacturing challenges (eg, lentiviral vector shortages), can limit CAR-T supply.

Although there is hope that creative solutions, such as outpatient delivery of CAR-T care or point-of-care manufacturing, will increase capacity and enhance access, in the current state of CAR-T as a limited resource, an ethical framework to ensure equitable patient allocation and fair decision-making is needed. A framework guards against potential biases of clinicians who may be moved by potentially discriminatory beliefs and attitudes. It may also contribute to a climate of patient trust in the health care system by ensuring decision-making is reasonable, fair, and transparent, with opportunity for appeals. On the whole, following an ethical framework contributes to the overall legitimacy of the outputs of the decision-making process and reflects the guiding principle of A4R, procedural justice.

The purpose of this perspective was to describe our approach to applying a well-defined ethical framework, A4R, to the challenges of CAR-T prioritization. We share our learnings and preliminary tools, encouraging other institutions to modify them for their own use. Our hope is that the description of our process will help advance fair and equitable patient access to CAR-T at the program level. For programs adopting our tools or process, we strongly recommend that they implement an A4R approach that engages relevant partners, as specific contexts and perspectives may yield important differences and unique considerations. Involving a bioethicist skilled in the A4R process and democratic deliberation to mitigate pitfalls, such as power imbalances, is an important consideration. There is also a need to develop a transparent formal appeals mechanism and for public regulation of the process to ensure that the publicity and enforcement conditions of A4R are met, conditions that we are still working to achieve.

Next steps at our institution are underway to evaluate the usability and acceptability of the ethical framework and associated prioritization tools. We plan to gain the perspective of end users to inform further refinements and modifications, and to assess the feasibility of clinical implementation of the tools/process in the “real world.”

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the members of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Ethics and Cell Therapy Working Group for their contributions to the patient prioritization to chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy initiative; a complete membership list appears in ”Appendix.”

Authorship

Contribution: C.I.C. and J.A.H.B. conceived the project; and C.I.C., G.A.J., and J.A.H.B. collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data and contributed to the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.I.C. declares consultancy, honoraria, and research funding for Gilead Sciences; consultancy and honoraria for Bristol Myers Squibb; and consultancy for Novartis, AbbVie, and Beigene. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Correspondence: Christine I. Chen, Division of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, 610 University Ave, Office 6-225, Toronto, ON M5G 1Z5, Canada; e-mail: christine.chen@uhn.ca; and Jennifer A. H. Bell, Department of Clinical and Organizational Ethics, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, 585 University Ave, 1 NU-163, Toronto, ON M5G 2N2, Canada; e-mail: jennifer.bell2@uhn.ca.

Appendix

The members of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre Ethics and Cell Therapy Working Group are Nupur Agarwal, Emily Barca, Lyndon Barnes, Rhida Bautista, Philippe Bedard, Jennifer Bell, Sabrina Bennett, Sita Bhella, Marcus Butler, Christine Chen, Sarah Coyle, Michael Crump, Celina Dara, Pamela Degendorfer, Julia Dobbin, Nicola Doyle, Lauren Finlay, Gregory Jeffries, Anthony Keating, Vishal Kukreti, John Kuruvilla, Arjun Law, Cheryl Liverpool, Tim Mt. Pleasant, Sarah Nagel, Giovanni Piza, Anca Prica, Adrian Sacher, Semira Sheikh, Lisa Tinker, Jody Tone, Andrew Winter, Karen Yee, and Christina Zeglinski.

References

Author notes

Presented in abstract form at the 65th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, New Orleans, LA, 12 December 2022.

For original data, please contact jennifer.bell2@uhn.ca.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.