In this issue of Blood, Salmerón-Villalobos et al have elucidated the molecular code of monomorphic posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLDs) in the pediatric population.1 Through an integrated molecular approach including fluorescence in situ hybridization, copy number arrays, and targeted gene sequencing, the study establishes the genetic landscape of monomorphic PTLD with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and Burkitt lymphoma (BL) histology. By comparing pediatric cases of PTLD-DLBCL and PTLD-BL to their counterparts occurring as de novo lymphomas in immunocompetent children and PTLD-DLBCL in adults, this study seeks to better understand the translational biology of pediatric monomorphic B-cell PTLD. It addresses a critical gap in knowledge that may enhance our understanding of the classification of PTLD and expected patterns of treatment response.

Children with advanced-stage, monomorphic PTLD with DLBCL histology can present with clinically aggressive disease including multifocal lymphoid masses, diffuse extranodal involvement, and an alarming disease burden on imaging studies. Selection of the optimal treatment regimen for these patients, particularly those with stage III disease, remains a formidable challenge. Some patients like this are cured with gentle therapeutic approaches, such as reduction of immune suppression, rituximab monotherapy, or low-dose chemoimmunotherapy (as reaffirmed within this cohort). Others, though, resemble clinical scenarios akin to de novo pediatric mature B-cell lymphomas and require intensive multiagent chemoimmunotherapy. Such polarizing heterogeneity in pediatric monomorphic PTLD-DLBCL renders it a high-stakes clinical dilemma, especially considering the potential life-threatening and transplant-threatening complications of intensive chemotherapy.

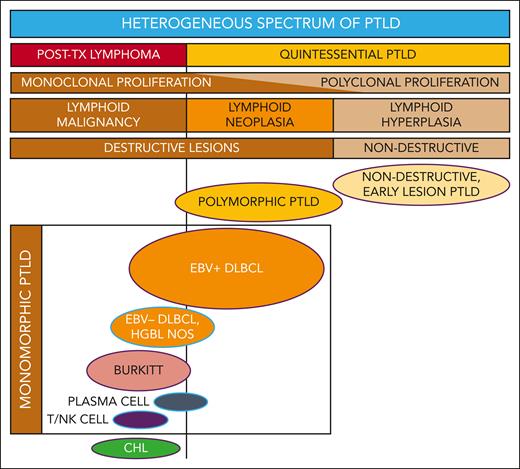

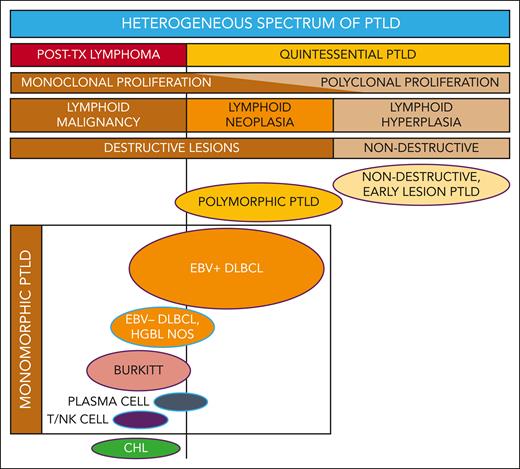

PTLD includes a broad spectrum of lymphoproliferation (see figure) ranging from nondestructive, early lesion PTLD (characterized as polyclonal, reactive B-cell hyperplasia) to polymorphic PTLD (polymorphic, often monoclonal, neoplastic, destructive lesions) to monomorphic and classical Hodgkin lymphoma PTLD (demonstrating transformation to or toward malignant lymphoma).2 It is challenging to unify such a heterogeneous category of disease processes that are characterized by drastically different clinical patterns, therapeutic approaches, and survival outcomes.

Reconceptualizing the framework for categorizing the heterogeneous spectrum of lymphoproliferation in pediatric PTLD. Traditional PTLD classification is based on morphological features stratified as nondestructive, polymorphic, monomorphic, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) PTLD. This revised stratification highlights the heterogeneity of monomorphic PTLD and demarcates a threshold beyond which quintessential EBV-driven lymphoid hyperplasia or neoplasia transforms into malignant lymphoma. EBV+ DLBCL in particular straddles the threshold between quintessential PTLD and posttransplant lymphoma. Ovals with purple borders indicate entities that are typically EBV+, and ovals with blue borders indicate entities that are often EBV−. HGBL NOS, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified and other gray-zone, Burkitt-like mature B-cell lymphomas; PLASMA CELL, plasma cell neoplasm; T/NK CELL, T/NK-cell lymphoma; TX, transplant.

Reconceptualizing the framework for categorizing the heterogeneous spectrum of lymphoproliferation in pediatric PTLD. Traditional PTLD classification is based on morphological features stratified as nondestructive, polymorphic, monomorphic, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL) PTLD. This revised stratification highlights the heterogeneity of monomorphic PTLD and demarcates a threshold beyond which quintessential EBV-driven lymphoid hyperplasia or neoplasia transforms into malignant lymphoma. EBV+ DLBCL in particular straddles the threshold between quintessential PTLD and posttransplant lymphoma. Ovals with purple borders indicate entities that are typically EBV+, and ovals with blue borders indicate entities that are often EBV−. HGBL NOS, high-grade B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified and other gray-zone, Burkitt-like mature B-cell lymphomas; PLASMA CELL, plasma cell neoplasm; T/NK CELL, T/NK-cell lymphoma; TX, transplant.

Nondestructive and polymorphic PTLDs are prototypical Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-driven PTLDs. Such quintessential PTLD in children is conceptually built on a framework in which acquired immune suppression in patients that are often EBV immune-naive creates susceptibility to varying degrees of EBV-driven lymphoproliferation.3 For such patients, restoration of the immune response and EBV-directed therapeutic strategies are often curative.

Monomorphic PTLD is a problematic category because it encompasses an expansive array of posttransplant lymphoid neoplasia that does not neatly fit this conceptual framework. Some patients with EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL have a favorable response to less intensive therapy such as rituximab and thus belong in the spectrum of quintessential PTLD. In contrast, others have relapsing or refractory disease after standard or even novel EBV-directed or low-dose chemoimmunotherapy strategies. For these latter patients, EBV may represent only one of multiple pathogenic factors driving lymphomagenesis. Such patients, plus many with EBV-negative PTLD-DLBCL, are similar to patients with PTLD-BL—they typically require aggressive multiagent chemotherapy for curative outcomes.4,5 Additionally, other rare monomorphic entities, such as PTLD with any mature T-cell or natural killer (NK)-cell lymphoma histology or classical Hodgkin lymphoma PTLD, also require treatment with disease-specific chemotherapy regimens typically given to patients who are immunocompetent.

Successive generations of international clinical trials for pediatric PTLD have repeatedly demonstrated an event-free survival of approximately 70% after treatment with low-dose chemotherapy with or without rituximab.6-8 Data from the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster group demonstrated that 53% of patients could achieve durable complete remission with rituximab alone.9 Throughout these studies, polymorphic PTLD and monomorphic DLBCL have shown similar outcomes, and the only prognostic factors identified were the presence of stage IV disease and BL histology.7,8 Despite the efficacy of rituximab in a significant subset of patients, and despite novel development of EBV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte immunotherapy, event-free survival for pediatric PTLD over the past 20 years has plateaued at ∼70% after treatment with milder, rituximab or low-dose chemoimmunotherapy-based approaches.10 Identification of patients that require intensive multiagent chemoimmunotherapy has remained elusive with neither traditional PTLD morphological or histological classification or clinical criteria reliably identifying this high-risk subset.

This study examined monomorphic PTLD to try to identify which patients can be successfully treated with low-intensity immunotherapy-based interventions and which patients require a full-intensity chemoimmunotherapy approach. Specifically, it demonstrated that pediatric PTLD-DLBCL is genetically less complex and biologically distinct—from both disease in adults as well as de novo pediatric DLBCL—and that somatic alterations in genes involved in cell cycle and Notch pathways were associated with worse outcomes.1 In contrast, they also showed that the mutational profile of PTLD-BL shares biological overlap with de novo EBV-positive BL, thus providing translational evidence supporting the widely accepted practice of treating PTLD-BL with the intensive chemotherapy regimens used for patients that are immunocompetent.5,8 BL, after all, is characterized by its principal molecular feature—C-MYC rearrangement. Results from this study offer evidence that a molecular classification system for pediatric PTLD may have potential to prospectively provide more precise risk stratification and, ideally, tailor therapy.

PTLD classification systems built upon morphological features are generally effective but have some important shortcomings, specifically limitations that pertain to monomorphic DLBCL. These data suggest the need to expand the PTLD classification to integrate molecular characteristics with traditional morphology. Such a new classification should consider distinguishing 2 overarching categories—one being the classic spectrum of quintessential PTLD including nondestructive, polymorphic, and monomorphic EBV+ PTLD-DLBCL, and the second being a heterogenous group categorized as posttransplant lymphomas considered analogous to those occurring in the setting of other underlying (inherited or acquired) immunodeficiency syndromes (see figure). Within this framework, the biologically and clinically heterogeneous entity of PTLD-DLBCL would straddle both categories. Next-generation targeted sequencing studies identified worse outcomes for PTLD-DLBCL in association with somatic mutations in cell cycle and Notch molecular pathways, which suggests a role for molecular diagnostics to categorize individual cases with greater precision. Future studies are needed to prospectively evaluate molecular biomarkers in larger cohorts for clinical validation. Ideally, a risk-stratification system for pediatric PTLD would reliably identify those patients that may be effectively treated with milder, EBV-directed or rituximab-based therapies, thus sparing them the severe toxicities of intensive multiagent chemotherapy. It should simultaneously be capable of identifying the high-risk patients for whom the risks of intensive therapy are justified by significantly improved chances for cure.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.