In this issue of Blood, Eichenauer et al1 concludes that contemporary Hodgkin lymphoma–directed treatment is highly active in newly diagnosed early-stage nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL). Their important findings originate from subgroup analyses of 2 randomized Hodgkin lymphoma trials. Owing to the scarcity of NLPHL, large randomized trials are absent. Thus, evidence for treatment decisions is hard to find.

However, as the authors also point out, NLPHL is not a classic Hodgkin lymphoma but rather a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, specifically a CD20+ indolent B-cell lymphoma.2,3 I sometimes compare the old terms Hodgkin vs non-Hodgkin lymphoma to ornithologists separating owls from non-owls. The terminology is good for describing the owl/Hodgkin lymphoma but not for other birds such as hummingbirds and albatrosses.

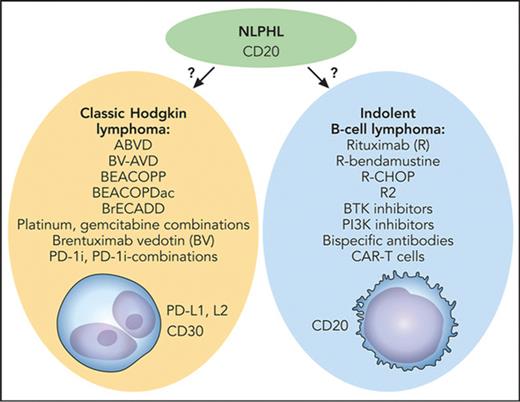

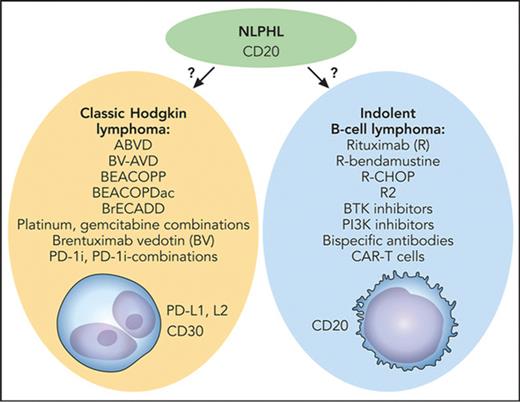

The key question with this rare disease is whether to treat according to the best available clinical evidence in which treatment decisions were driven by tradition (Hodgkin lymphoma–directed therapy) or by biological insights (the indolent B-cell lymphoma character of the disease) paired with clinical evidence that is not as quantitatively impressive (see figure).

Medical therapy for NLPHL: tradition vs biology. The key question is whether to treat with Hodgkin lymphoma–directed therapy (left) or as an indolent B-cell lymphoma (right). BEACOPDac, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, dacarbazine; BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone; BrECADD, brentuximab vedotin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, dacarbazine, dexamethasone; BV-AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin (Adriamycin), vinblastine, and dacarbazine; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Medical therapy for NLPHL: tradition vs biology. The key question is whether to treat with Hodgkin lymphoma–directed therapy (left) or as an indolent B-cell lymphoma (right). BEACOPDac, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, dacarbazine; BEACOPP, bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone; BrECADD, brentuximab vedotin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, dacarbazine, dexamethasone; BV-AVD, brentuximab vedotin plus doxorubicin (Adriamycin), vinblastine, and dacarbazine; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Biologically, there is no doubt of the indolent B-cell lymphoma character of NLPHL, which is also reflected in the alternative naming, NLP B-cell lymphoma.2 This is also consistent with findings of a very good long-term overall survival, despite a lack of plateau in the progression-free survival (PFS) curves.4 The treatment outcome with traditional Hodgkin lymphoma therapy is very good indeed, as shown by Eichenauer et al. At the same time, more and more evidence of CD20-directed therapy is emerging, but there is still a lack of very long-term follow up.5-8 One register-based study has suggested a better overall survival for patients treated with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab.9 Salvage attempts also have been made with BTK inhibitors.10

The authors examined patients with NLPHL treated as classic Hodgkin lymphoma in the large academic randomized clinical trials HD16 (early-stage favorable) and HD17 (early-stage unfavorable). They examined the outcome of early-stage NLPHL treated with contemporary Hodgkin lymphoma therapy and also the role of interim positron emission tomography (PET) in these patients. It was known that Hodgkin lymphoma–directed therapy is effective, but the outcome with the modern approach implemented in these studies was not previously evaluated. The article is well written, and the methodology for answering the questions is solid. Considering the rarity of NLPHL, the size of the cohort is respectable, giving enough power for the necessary statistical analyses. Owing to the fact that patients with NLPHL have 100% overall survival and similar PFS as patients with classic Hodgkin lymphoma, except a tendency to poorer PFS for early-stage patients who were not irradiated, the authors draw the conclusion that classic Hodgkin lymphoma therapy is a suitable option for patients with early-stage NLPHL. The necessity of radiotherapy for early stages, irrespective of interim PET result, is noted and mentioned in the conclusion. There also was an encouraging absence of histological transformation.

The findings in the article are novel, describing modern therapy not previously evaluated for NLPHL. However, there are caveats, the most important being that NLPHL is already treated as an indolent B-cell lymphoma in many countries with a rituximab- and radiotherapy-based approach, using primary chemotherapy only for a limited number of patients. This kind of approach is significantly less toxic than treating all with chemotherapy. Further, as the authors point out in the conclusion, the optimal chemotherapy approach still needs to be defined. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) might be the most proven owing to tradition, but biologically there is no rationale for using Hodgkin lymphoma–directed chemotherapy instead of chemotherapy with better results for indolent B-cell lymphomas.

In conclusion, the results of this study give important further evidence for primary therapy of early-stage NLPHL and advance the field. At the same time, the international trend is to treat more like indolent B-cell lymphoma; however, there is a lack of solid evidence of its superiority. There is certainly a need for a randomized trial specifically for NLPHL, something that would take a substantial international effort to achieve. Also, standard and experimental indolent B-cell lymphoma–directed approaches beyond single rituximab and radiotherapy, such as R-bendamustine, R2, BTK- and PI3K-inhibitors, bispecific antibodies, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells should ideally be tested on relapsing NLPHL. This could be achieved by including patients with NLPHL in relapsed/refractory indolent B-cell lymphoma trials.

You are Mr. Owl. I am Ms. Hummingbird. We maybe came from different species but as long as you're a bird, I'm a bird too.—Glad Munaiseche

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.M. received honoraria from Roche, Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Takeda (not related to this article).