Key Points

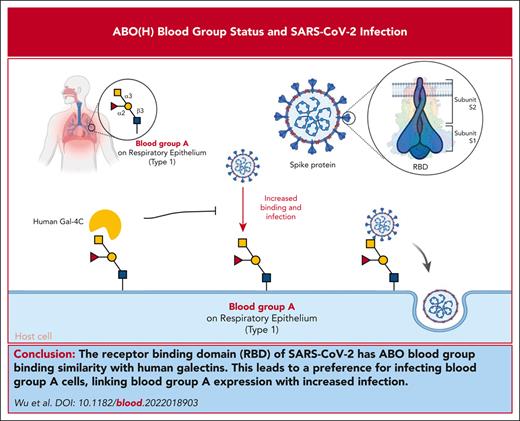

The RBD of SARS-CoV-2 bears sequence and overall ABO blood group binding similarity with human galectins.

SARS-CoV-2 preferentially infects blood group A cells, providing a direct link between blood group A expression and increased infection.

Abstract

Among the risk factors for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), ABO(H) blood group antigens are among the most recognized predictors of infection. However, the mechanisms by which ABO(H) antigens influence susceptibility to COVID-19 remain incompletely understood. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2, which facilitates host cell engagement, bears significant similarity to galectins, an ancient family of carbohydrate-binding proteins. Because ABO(H) blood group antigens are carbohydrates, we compared the glycan-binding specificity of SARS-CoV-2 RBD with that of galectins. Similar to the binding profile of several galectins, the RBDs of SARS-CoV-2, including Delta and Omicron variants, exhibited specificity for blood group A. Not only did each RBD recognize blood group A in a glycan array format, but each SARS-CoV-2 virus also displayed a preferential ability to infect blood group A–expressing cells. Preincubation of blood group A cells with a blood group-binding galectin specifically inhibited the blood group A enhancement of SARS-CoV-2 infection, whereas similar incubation with a galectin that does not recognize blood group antigens failed to impact SARS-CoV-2 infection. These results demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 can engage blood group A, providing a direct link between ABO(H) blood group expression and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) continues to infect millions of individuals worldwide. However, individuals are not equally susceptible to infection.1 Many studies have demonstrated that the first polymorphism described in the human population, ABO(H) blood group antigens, are associated with an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection.2-4 Although conflicting data exist, the most common findings suggest that individuals with blood group A exhibit an increased risk of infection compared with blood group O individuals.3 However, the mechanism by which ABO(H) blood group status influences SARS-CoV-2 infection has remained incompletely defined.

Study design

SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domains (RBDs) and galectins were cloned, purified, and subjected to glycan microarray or flow cytometric analysis, as previously outlined.5-10 Details regarding CHO cells expressing ACE2 and blood group A, Lea, ALeb, or the H antigen (blood group O), SARS-CoV-2 RBD modeling with blood group A, SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan-Hu-1, Delta, and Omicron) infection of blood group A, Lea, ALeb, or O cells, and data sharing are outlined in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website).11,12

Results and discussion

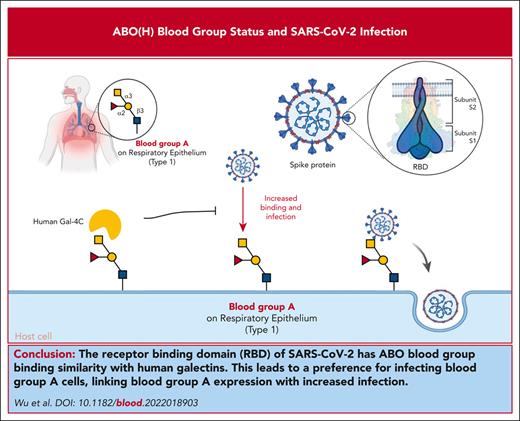

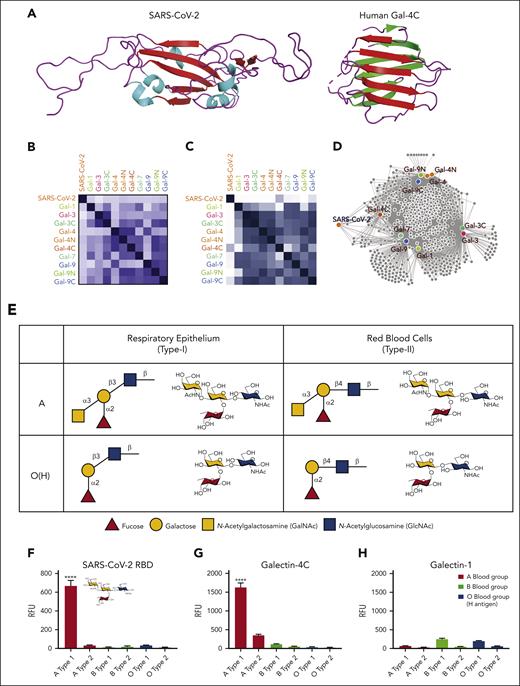

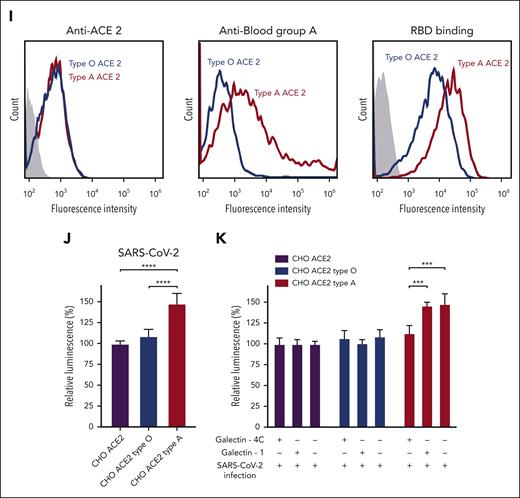

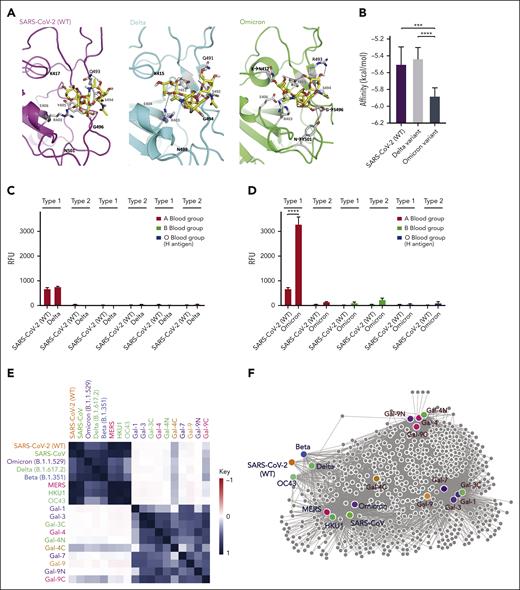

Within the viral surface spike protein, the RBD is responsible for recognizing host ACE2, allowing viral entry and infection.13 However, RBD also has remarkable structural and sequence similarity to an ancient family of proteins called galectins14 (Figure 1A). Galectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins previously shown to engage ABO(H) antigens,6,15 raising the possibility that the RBD may exhibit similar binding characteristics toward ABO(H), as observed for galectins. Sequence analysis of the RBD and galectins demonstrated that some galectins possess up to 11% sequence identity with SARS-CoV-2 WT (Wuhan-Hu-1) (Figure 1B). Although previous data suggested that the WT SARS-CoV-2 RBD may exhibit distinct recognition of ABO(H) antigens,14 to directly compare the glycan-binding specificity of the RBD with human galectins, we analyzed the glycan-binding specificity of the RBD and galectins using a glycan microarray populated with distinct variants of ABO(H) blood group antigens.15,16 The RBD exhibited glycan-binding specificity that overlapped with distinct members of the galectin family (Figure 1C), where the C-terminal domain of galectin-4 (Gal-4C) exhibited the highest level of glycan-binding similarity (Figure 1D). Direct comparison of binding to ABO(H) antigens found on the surface of red blood cells (type 2) or respiratory epithelial cells (type 1) demonstrated that RBD and Gal-4C preferred type 1 blood group A structures found on respiratory epithelial cells17 (Figure 1E,F,G). In contrast, galectin-1 (Gal-1) failed to exhibit any blood group antigen-binding preference (Figure 1H). These results demonstrate that the RBD not only possesses structural similarities to galectins but also exhibits similar glycan-binding preferences to some galectin family members.

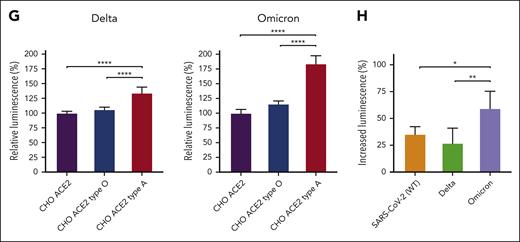

The ability of RBD to recognize blood group A raises the possibility that this interaction could directly influence SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, as blood group and ACE2 expression can be highly variable in primary epithelial cells,18 it can be challenging to specifically test the contribution of blood group A to infection outcomes. To specifically examine the impact of blood group A on SARS-CoV-2 infection, we engineered CHO cells, which have been leveraged for decades to study the impact of glycosylation on cellular processes,19 to express both ACE2 and type 1 blood group A or H antigen (present in blood groups A and O, respectively) normally found on respiratory epithelial cells.17 Using this approach, cells with identical ACE2 levels were generated that possessed either blood group A or H antigen (blood group O) (Figure 1I). Consistent with the increased binding of RBD to blood group A in the glycan microarray, enhanced RBD binding was also observed in blood group A–expressing cells (Figure 1I). To determine whether increased SARS-CoV-2 RBD binding affects cellular sensitivity to infection, we next examined SARS-CoV-2 infection in blood group A or O cells. Blood group A cells were significantly more likely to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 than blood group O cells (Figure 1J). Given the similarities in glycan-binding specificity between Gal-4C and the RBD, we determined whether Gal-4C can modulate SARS-CoV-2 infection20; as a control, Gal-1, which failed to engage blood group antigens, was examined in parallel. Preincubation of cells with Gal-4C specifically inhibited SARS-CoV-2 infection of blood group A–expressing cells, while failing to impact infection of blood group O cells, consistent with the binding profile of Gal-4C (Figure 1K). In contrast, Gal-1, which failed to exhibit any blood group-binding preference, did not affect SARS-CoV-2 infection in the blood group A or O cells (Figure 1K).

Among the variants that have emerged since the onset of the pandemic, many mutations can be found in regions of the RBD predicted to recognize glycans (Figure 2A),21 raising the possibility that these changes may alter glycan recognition. Modeling-based approaches suggest that key residues mutated in variants are predicted to enhance blood group A binding, specifically in the Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) (Figure 2B). To directly test this, we compared the glycan binding of the Delta (B.1.617.2) and Omicron variants to ABO(H) blood group antigens. Consistent with the possibility that Omicron mutations may enhance blood group A recognition, higher binding toward blood group A was observed (Figure 2C-D). Additional analysis of each RBD variant demonstrated distinct alterations in glycan binding (Figure 2E). These changes in glycan preference appeared to be unique to each variant, as similar changes were not observed when examining the binding preferences of SARS-CoV, MERS, or even the common cold strains HKU1 and OC43 RBDs (Figure 2E). Despite subtle differences in glycan-binding specificity between the variants and other cold coronavirus strain RBDs, the glycan-binding specificity of all RBDs analyzed remained more similar to each other than galectins (Figure 2F), suggesting that some conservation in glycan-binding specificity exists. To determine whether the Delta and Omicron strains retain the ability to not only recognize blood group A on the glycan microarray but also exhibit preferential infection of blood group A–expressing cells, we next examined blood group O or blood group A cell sensitivity to infection. Although the Delta strain did indeed exhibit a higher preference for blood group A–expressing cells, the Omicron variant displayed the highest level of blood group A preference (Figure 2G). Compared with the SARS-CoV-2 and Delta strains, the Omicron variant exhibited the highest blood group A selectivity (Figure 2H). Lewis antigens, which can impact SARS-CoV-2 infectious risk,22,23 differentially influenced SARS-CoV-2, Delta, and Omicron RBD binding and infection (supplemental Figure 1). The impact of blood group preference was not limited to type 1 blood group A, as extended glycan array analysis revealed enhanced Delta and Omicron RBD binding to type 3 blood group B (supplemental Figure 1).

These results demonstrate the direct effect of blood group A on viral infection and answer a fundamental question regarding the increased sensitivity of blood group A individuals to SARS-CoV-2. Although blood group A can influence SARS-CoV-2 infection, this increase can vary, ranging from 25% to 50% increase in infection depending on the variant tested. These results largely match clinical observations, where odds ratios range from no impact to a 47% increase in infection among blood group A individuals.2,3 Additional polymorphisms, including Lewis antigens,22,23 may modulate the host sensitivity to SARS-CoV-2. Similarly, although galectin expression at sites of infection remains incompletely understood, host galectin-4 may modulate the influence of ABO(H) on SARS-CoV-2 infection.24 Thus, variations in ACE2 levels, blood group A expression, galectin levels, and other factors are likely to influence the overall risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a given population.25 The present results provide a mechanism by which blood group A itself may directly influence SARS-CoV-2 infectious risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate helpful discussions with Akul Mehta, Patricia Zerra, and Satheesh Chonat.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01 HL138656, R01 HL135575, and R01 HL165975 (S.R.S.), NIH National Cancer Institute grant U01 CA242109 (S.R.S.), and by NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R24GM137763 (R.D.C.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.-C.W., C.M.A., and H.-M.J. designed and conducted key experiments; W.F.G.-B., H.P.V., N.C., A.S.N., and J.D.R. generated key reagents; K.R.P., M.F.R., R.P.J., A.P., C.D.J., D.K., D.R.W., S.R.-N., and R.D.C. provided critical oversight in the design and execution of these studies; and S.-C.W., C.M.A., and S.R.S. wrote the manuscript, which was additionally commented on and edited by the remaining authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.R.S. has consulted for Novartis, Cellics, Argenex, and Alexion and has received speaking honoraria from Grifols. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sean R. Stowell, Joint Program in Transfusion Medicine Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, 630E New Research Building, 77 Ave Louis Pasteur, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: srstowell@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

Data on all reagents will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, Sean R. Stowell (srstowell@bwh.harvard.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.