Introduction: Sickle cell disease (SCD) has the highest U.S. disease burden among Black and Hispanic populations, who more commonly live in urban areas with poor ambient air quality. The effect of air pollution exposure and social environmental factors on health outcomes in SCD have not been extensively studied, especially among children, and may further contribute to health disparities.

Objectives: This study aims to examine the associations between air pollution exposure and acute respiratory and pain events and to determine whether neighborhood-level social disadvantage would modify their associations.

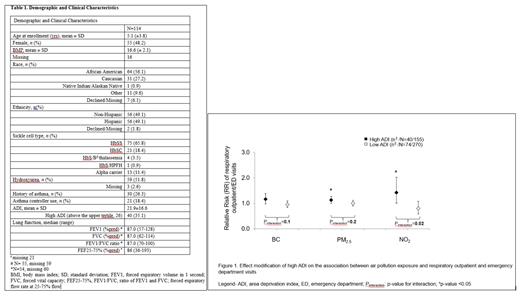

Methods: We collected retrospective data on unscheduled outpatient visits, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospital admissions for respiratory events (i.e., respiratory tract infections, asthma exacerbation, acute chest syndrome) and vaso-occlusive pain crises requiring hospitalization (VOCs) for children with SCD in a tertiary care center in New York City (NYC) from 2015-2018. A total of 114 children with SCD (Table 1) were included in this study and had between 1-4 annual repeated measures of annual average air pollutants (i.e., black carbon (BC), fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), and nitrogen dioxide (NO 2)) with a total of 425 visits. Using home addresses, modeled data from the NYC Community Air Survey data were used to estimate street-level, annual average exposure to air pollution. The area deprivation index (ADI), a composite index of neighborhood-level social disadvantage, was dichotomized at the upper tertile (higher vs lower). Multivariable Poisson regression in generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used to estimate relative risks (RR), after adjusting for potential covariates.

Results: Overall, there were no significant associations between air pollution levels and acute respiratory and pain events among children with SCD. When stratified by ADI, increased exposure to PM 2.5 and NO 2, but not BC, was significantly associated with more frequent respiratory outpatient and ED visits among children residing in higher ADI neighborhoods (RR (95%CI)= 1.13 (1.00, 1.28) and 1.43 (1.01, 2.02) for PM 2.5 and NO 2, respectively, p<0.05 for all), but not among those in lower ADI neighborhoods (P-value for interaction=0.2 and 0.02 for PM 2.5 and NO 2, respectively) (Figure 1). Associations of air pollution with hospital admissions and VOCs were not observed for neither high ADI nor low ADI neighborhoods (p-value>0.05).

Conclusions: Exposure to air pollutants increased respiratory complications among children living in deprived neighborhoods.

Disclosures

Green:AddMedica: Other: Donated study drug for an NIH-funded clinical trial.