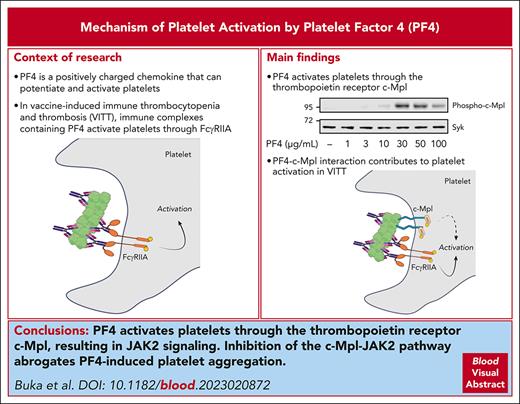

PF4 activates the thrombopoietin receptor c-Mpl in platelets, resulting in JAK2-STAT3/5 signaling.

Inhibition of kinase activity of JAK2 abrogates platelet aggregation by PF4.

Visual Abstract

Platelet factor 4 (PF4) is an abundant chemokine that is released from platelet α-granules on activation. PF4 is central to the pathophysiology of vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT) in which antibodies to PF4 form immune complexes with PF4, which activate platelets and neutrophils through Fc receptors. In this study, we show that PF4 binds and activates the thrombopoietin receptor, cellular myeloproliferative leukemia protein (c-Mpl), on platelets. This leads to the activation of Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) and phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 and STAT5, leading to platelet aggregation. Inhibition of the c-Mpl–JAK2 pathway inhibits platelet aggregation to PF4, VITT sera, and the combination of PF4 and IgG isolated from VITT patient plasma. The results support a model in which PF4-based immune complexes activate platelets through binding of the Fc domain to FcγRIIA and PF4 to c-Mpl.

Introduction

Platelet factor 4 (PF4), also known as C-X-C motif ligand 4, is a 7.8-kDa chemokine that is released from platelet α-granules.1 PF4 forms tetramers with a compact globular structure and a strong equatorial positive charge,2,3 and it binds strongly to negatively charged molecules, including endothelial proteoglycans and infectious agents.4,5 Antibodies to PF4 underlie the pathogenesis of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT)6,7 and vaccine-induced immune thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT)8,9 by forming immune complexes with PF4.

The direct effect of PF4 on platelets has not been extensively studied. PF4 potentiates activation of platelets to threshold doses of thrombin10 and has recently been shown to induce platelet aggregation,11 but the underlying mechanism has not been investigated. In this study, we show that PF4 binds the thrombopoietin (TPO) receptor, c-Mpl, inducing activation of Janus kinase 2 (JAK2). The JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib blocks platelet aggregation to PF4 and to VITT antibodies.

Study design

For a full description of all reagents and methods, see supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website).

Ethical approval

Approval for collecting blood from healthy volunteers was granted by the University of Birmingham’s Internal Ethical Review Committee (ERN_11-0175APP22). Collection of serum and plasma from patients with VITT at University Hospitals Birmingham National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust was authorized by the University of Birmingham Human Bioresource Centre (approval 15/NW/0079). Samples were obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Key reagents

PF4 was obtained from ChromaTec GmbH (Greifswald, Germany), collagen-related peptide (CRP) from CambCol Ltd (Ely, United Kingdom), recombinant human thrombopoietin (TPO) from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL), ruxolitinib from Stratech Scientific (Ely, United Kingdom), recombinant c-Mpl (TpoR; 4444-TR) from Biotechne (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and c-Mpl polyclonal blocking antibody PA5-47042 from Invitrogen (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Light transmission aggregometry

Washed platelets (2 × 108/mL) were prepared as described.12 Platelets were prewarmed to 37 °C and preincubated with PF4 and/or inhibitors for 5 minutes. Agonists were added under stirring conditions (1200 rpm), and aggregation was measured for 7 to 30 minutes.

Protein phosphorylation

Platelets (4 × 108/mL) prewarmed to 37 °C were pretreated with eptifibatide (9 μM). Reactions were terminated after 10 minutes, and samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, electrotransferred, and western blotted. Mass spectrometry was performed by excision of material at ≈95 kDa on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. Full details are included in supplemental Methods.

Data presentation

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and were considered significant at P < .05. Details on statistical packages can be found in supplemental Methods.

Results and discussion

PF4 activates platelets through a c-Mpl-JAK2-STAT3/5 pathway

PF4 stimulated biphasic platelet aggregation over 3 to 100 μg/mL (0.4-12.8 μM) with a gradual initial phase followed by a rapid second phase (Figure 1A). In some donors, the dose-response curve was bell shaped, with the second phase often absent at higher concentrations of PF4 (Figure 1A). Aggregation was abrogated in the presence of eptifibatide, demonstrating that it was mediated through activation of integrin glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (supplemental Figure 1).

PF4 induces aggregation through binding to c-Mpl and activation of the JAK2-STAT3/5 pathway. (A) PF4 dose-response assessed by light transmission aggregometry. Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were stirred at 1200 rpm for 1 minute before addition of PF4. (Ai) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Aii) Quantification of aggregation (area under the curve [AUC] per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 4-13). (B) Phosphorylation of STAT3, STAT5, JAK2, and c-Mpl in PF4-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets (4 × 108/mL) were preincubated with eptifibatide (9 μM) for 10 minutes before PF4 addition. After 10 minutes, platelets were lysed. Protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and analyzed for panphosphotyrosine (4G10), phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; Tyr705), phosphorylated STAT5a/b (pSTAT5a/b; Tyr694/699), phosphorylated c-Mpl (pc-Mpl; Tyr626), and Syk. For JAK2, samples were immunoprecipitated (IP) before western blotting for panphosphotyrosine with 4G10 (pJAK2). (Bi) Representative western blots using monoclonal antibodies to phosphotyrosine (4G10) and to pSTAT3 and pSTAT5a/b. (Bii) Representative western blot using 4G10 after JAK2 IP. (Biii) Representative western blot using an antibody to pc-Mpl. (Biv) Quantification of pixel lane intensities for phosphorylation of STAT3 (dark blue triangles), STAT5 (red circles), c-Mpl (light blue diamonds), and JAK2 (green squares) measured as fold change relative to resting (n = 3). Values are normalized for loading controls. (C) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) showing binding of PF4 to c-Mpl. C-Mpl was conjugated directly onto the chip and PF4 flowed over. All sensograms shown are double reference subtracted, and at least 2 replicates were injected per cycle with experimental replicates of n = 3. RU: response units. Statistical analyses by a 1-way analysis of variance; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001.

PF4 induces aggregation through binding to c-Mpl and activation of the JAK2-STAT3/5 pathway. (A) PF4 dose-response assessed by light transmission aggregometry. Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were stirred at 1200 rpm for 1 minute before addition of PF4. (Ai) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Aii) Quantification of aggregation (area under the curve [AUC] per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 4-13). (B) Phosphorylation of STAT3, STAT5, JAK2, and c-Mpl in PF4-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets (4 × 108/mL) were preincubated with eptifibatide (9 μM) for 10 minutes before PF4 addition. After 10 minutes, platelets were lysed. Protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and analyzed for panphosphotyrosine (4G10), phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; Tyr705), phosphorylated STAT5a/b (pSTAT5a/b; Tyr694/699), phosphorylated c-Mpl (pc-Mpl; Tyr626), and Syk. For JAK2, samples were immunoprecipitated (IP) before western blotting for panphosphotyrosine with 4G10 (pJAK2). (Bi) Representative western blots using monoclonal antibodies to phosphotyrosine (4G10) and to pSTAT3 and pSTAT5a/b. (Bii) Representative western blot using 4G10 after JAK2 IP. (Biii) Representative western blot using an antibody to pc-Mpl. (Biv) Quantification of pixel lane intensities for phosphorylation of STAT3 (dark blue triangles), STAT5 (red circles), c-Mpl (light blue diamonds), and JAK2 (green squares) measured as fold change relative to resting (n = 3). Values are normalized for loading controls. (C) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) showing binding of PF4 to c-Mpl. C-Mpl was conjugated directly onto the chip and PF4 flowed over. All sensograms shown are double reference subtracted, and at least 2 replicates were injected per cycle with experimental replicates of n = 3. RU: response units. Statistical analyses by a 1-way analysis of variance; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001.

These concentrations are higher than the plasma concentration of PF4, which is in the region of 0.8 to 50 ng/mL.13 However, the vast majority of PF4 is contained in platelet α-granules. On the basis of data reporting 500 000 copies of PF4 per platelet,14,15 the whole blood concentration is ≈1.5 μg/mL, with higher local concentrations formed on α-granule release and being concentrated at surfaces through glycosaminoglycan binding. In addition, these are typical concentrations that are used in assays that are widely used in studies of VITT and HIT, as well as in the diagnosis of HIT.16,17

To investigate the mechanism of activation, we measured tyrosine phosphorylation of whole cell lysates by western blotting using the anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody, 4G10. PF4 stimulated a concentration-dependent increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of a prominent doublet at 95 kDa (Figure 1Bi, arrows). Analysis by mass spectrometry revealed the presence of a signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 5a/b peptide phosphorylated at Tyr 694/699 (supplemental data file). These findings were confirmed by western blot analysis using a phosphospecific antibody to STAT5a/b (Figure 1Bi). STAT3 was also identified by mass spectrometry and shown to be phosphorylated on Tyr704 using a phosphospecific antibody (Figure 1Bi).

The STAT family of transcription factors is phosphorylated in platelets downstream of the c-Mpl–JAK2 pathway.18 In line with this, PF4 stimulated dose-dependent phosphorylation of JAK2 (Figure 1Bii) and c-Mpl (Tyr626) (Figure 1Biii). The dose-response relationships for phosphorylation of all 4 proteins were similar to that for aggregation (Figure 1Biv).

Direct binding of PF4 to c-Mpl was shown by surface plasmon resonance with an estimated affinity constant (KD) of PF4 flowed over recombinant c-Mpl of 744 ± 19 nM (corresponding to 5.8 μg/mL) (Figure 1C). The affinity constant represents a net sum of affinity and avidity due to the tetrameric nature of PF4. Modeling of the binding of PF4 to c-Mpl by AlphaFold19,20 (mean predicted local distance difference test (pLDTT) of 69 for both PF4 and TPO models, indicating a reasonable measure of confidence for the models) suggests that the interaction occurs at a site adjacent to that of TPO (supplemental Figure 2A). Consistent with this, we observed reduced, but not complete, blockade of binding of TPO to-c-Mpl in the presence of PF4 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (supplemental Figure 2B).

The JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib inhibits platelet activation by PF4

The effect of the JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib21 on platelet activation by PF4 was investigated. For these studies, we used a concentration of ruxolitinib (100 nM) that had no effect on platelet activation by CRP or thrombin to minimize off-target effects (supplemental Figure 3). In high-responding donor platelets, ruxolitinib inhibited aggregation by PF4 (50 μg/mL) (Figure 2A) and TPO (100 ng/mL) (supplemental Figure 4A), and blocked potentiation of aggregation to a subthreshold concentration of CRP by PF4 (10 μg/mL) (Figure 2B) and TPO (10 ng/mL) (supplemental Figure 4B). The same concentration of ruxolitinib also inhibited phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5a/b by PF4 and TPO (Figure 2C). In contrast, aggregation induced by PF4 was not altered in the presence of the Src kinase inhibitor dasatinib (1 μM) or the Syk inhibitor PRT-060318 (1 μM), whereas both blocked aggregation to CRP (supplemental Figure 5).

JAK2 and c-Mpl blockade inhibit platelet responses to PF4. (A) Inhibition of PF4-induced platelet aggregation with ruxolitinib (Rux). Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were incubated with Rux (100 nM) or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] 0.01%) for 5 minutes and stirred at 1200 rpm before addition of PF4 (50 μg/mL). (Ai) Representative aggregation traces to PF4 (50 μg/mL) and Rux (100 nM). (Aii) Quantification of aggregation (area under the curve [AUC] per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 8) and analyzed by a paired t-test. (B) Enhancement of platelet aggregation to CRP by PF4 and inhibition by Rux. Prewarmed platelets were incubated with Rux (100 nM) for 5 minutes, followed by PF4 (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes before CRP (0.03 μg/mL) addition. (Bi) Representative aggregation traces. (Bii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 15 minutes and analyzed by a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (C) Rux inhibits STAT3 and STAT5a/b phosphorylation induced by PF4 and TPO. Prewarmed platelets (4 × 109/mL) were preincubated with eptifibatide (9 μM) for 10 minutes, then Rux (10-100 nM) for 5 minutes before stirring for an additional minute and PF4 (50 μg/mL) or TPO (100 ng/mL) addition. After 10 minutes, platelets were lysed. Protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and analyzed for panphosphotyrosine (4G10), phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; Tyr705), phosphorylated STAT5a/b (pSTAT5a/b; Tyr694/699), phosphorylated c-Mpl (pc-Mpl; Tyr626), and Syk. (Ci) Representative western blots. (Cii-iii) Quantification of pixel lane intensities for phosphorylation of (Cii) STAT3 and (Ciii) STAT5a/b, measured as percentage change relative to resting (n = 3). Values are normalized for loading controls. (D) PF4 enhancement of platelet aggregation to IgG isolated from a patient with VITT (IgG) and inhibition by Rux. Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were incubated with Rux (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO 0.01%) for 5 minutes, PF4 (10 μg/mL) or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) for 5 minutes, then stirred at 1200 rpm before IgG (100 μg/mL) addition. (Di) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Dii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 7) and analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. (E) PF4 enhancement of platelet aggregation to VITT serum (Serum) and inhibition by Rux. Platelets were prepared as for D with the addition of serum instead of IgG. (Ei) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Eii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 7) and analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. (F) As for E but with serum from a different patient. (G) Effect of polyclonal anti–c-Mpl blocking antibody (Ab) on platelet aggregation to PF4 and PF4 + VITT IgG. (Gi-ii) Washed platelets were incubated with anti–c-Mpl antibody (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes and stirred for an additional minute before PF4 (10 μg/mL) addition. (Gi) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Gii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 6) and analyzed by a paired t-test. (Giii-iv) As for Gi-Gii but preincubated with PF4 (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes after incubation with c-Mpl antibody before stirring and IgG addition. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

JAK2 and c-Mpl blockade inhibit platelet responses to PF4. (A) Inhibition of PF4-induced platelet aggregation with ruxolitinib (Rux). Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were incubated with Rux (100 nM) or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] 0.01%) for 5 minutes and stirred at 1200 rpm before addition of PF4 (50 μg/mL). (Ai) Representative aggregation traces to PF4 (50 μg/mL) and Rux (100 nM). (Aii) Quantification of aggregation (area under the curve [AUC] per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 8) and analyzed by a paired t-test. (B) Enhancement of platelet aggregation to CRP by PF4 and inhibition by Rux. Prewarmed platelets were incubated with Rux (100 nM) for 5 minutes, followed by PF4 (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes before CRP (0.03 μg/mL) addition. (Bi) Representative aggregation traces. (Bii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 15 minutes and analyzed by a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (C) Rux inhibits STAT3 and STAT5a/b phosphorylation induced by PF4 and TPO. Prewarmed platelets (4 × 109/mL) were preincubated with eptifibatide (9 μM) for 10 minutes, then Rux (10-100 nM) for 5 minutes before stirring for an additional minute and PF4 (50 μg/mL) or TPO (100 ng/mL) addition. After 10 minutes, platelets were lysed. Protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and analyzed for panphosphotyrosine (4G10), phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; Tyr705), phosphorylated STAT5a/b (pSTAT5a/b; Tyr694/699), phosphorylated c-Mpl (pc-Mpl; Tyr626), and Syk. (Ci) Representative western blots. (Cii-iii) Quantification of pixel lane intensities for phosphorylation of (Cii) STAT3 and (Ciii) STAT5a/b, measured as percentage change relative to resting (n = 3). Values are normalized for loading controls. (D) PF4 enhancement of platelet aggregation to IgG isolated from a patient with VITT (IgG) and inhibition by Rux. Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were incubated with Rux (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO 0.01%) for 5 minutes, PF4 (10 μg/mL) or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) for 5 minutes, then stirred at 1200 rpm before IgG (100 μg/mL) addition. (Di) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Dii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 7) and analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. (E) PF4 enhancement of platelet aggregation to VITT serum (Serum) and inhibition by Rux. Platelets were prepared as for D with the addition of serum instead of IgG. (Ei) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Eii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 7) and analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. (F) As for E but with serum from a different patient. (G) Effect of polyclonal anti–c-Mpl blocking antibody (Ab) on platelet aggregation to PF4 and PF4 + VITT IgG. (Gi-ii) Washed platelets were incubated with anti–c-Mpl antibody (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes and stirred for an additional minute before PF4 (10 μg/mL) addition. (Gi) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Gii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 6) and analyzed by a paired t-test. (Giii-iv) As for Gi-Gii but preincubated with PF4 (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes after incubation with c-Mpl antibody before stirring and IgG addition. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

Studies were designed to investigate whether PF4’s interaction with c-Mpl contributes to platelet activation in VITT. In this disorder, immune complexes consisting of PF4 and anti-PF4 IgG activate platelets through FcγRIIA.8,22 In most, but not all, cases, strong platelet activation by VITT serum requires the addition of PF4 (10 μg/mL).8,22 This is illustrated using an IgG fraction from the plasma of a patient with VITT, with activation observed only in the presence of PF4 (Figure 2D) and blocked by Syk, Src, and Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and the FcγRIIA blocking F(ab), IV.3, confirming a critical role for the low-affinity immune receptor in mediating activation (supplemental Figure 6A). In contrast, and as expected, Syk and Src inhibitors had no effect on PF4-mediated platelet aggregation or its ability to potentiate the response to a threshold dose of CRP (supplemental Figure 6B).

Strikingly, however, aggregation to VITT IgG and PF4 was also reduced by ruxolitinib (100 nM), suggesting that activation is mediated through synergy between FcγRIIA and c-Mpl (Figure 2D). Moreover, ruxolitinib blocked PF4 enhancement of aggregation to VITT sera from 2 other patients (Figure 2E-F), and reduced aggregation to a VITT serum sample that occurred without exogenous PF4 (Figure 2E). Confirmation that activation of JAK2 is downstream of c-Mpl in this model was shown using a polyclonal c-Mpl blocking antibody. In high-responding donor platelets that aggregated to 10 μg/mL PF4, the c-Mpl antibody completely blocked aggregation (Figure 2Gi-ii). The c-Mpl antibody also reduced platelet aggregation to VITT IgG and PF4 (Figure 2Giii-iv). These results provide evidence that activation of the c-Mpl–JAK2 pathway can contribute to platelet aggregation by anti-PF4 immune complexes.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that high concentrations of PF4 (>10 μg/mL) can induce robust platelet aggregation through the TPO receptor, c-Mpl, and that lower concentrations can potentiate platelet activation through the same pathway. In platelets, c-Mpl signals through the tyrosine kinase JAK2, which lies upstream of STAT3 and STAT5a/b, and several other pathways (namely, p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase,23 extracellular signal-regulated kinase–cytosolic phospholipase A2 ,24 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase).25 The relative contribution of each of these to platelet activation by PF4 is not known.

The findings have significance for the mechanism of platelet activation by VITT and HIT sera, with the binding of PF4 to c-Mpl supporting activation. In the context of VITT, binding of PF4 to c-Mpl might increase the functional affinity of immune complexes for platelet binding and increase the avidity of the antibody-FcγRIIA interaction. These findings may have a similar relevance for HIT, where, in addition, there may be synergy with the activation of platelet endothelial aggregation receptor 1 (PEAR1) by heparin.26 The interactions of these pathways are shown schematically in supplemental Figure 7 and may contribute to the variation in sensitivity of donor platelets to VITT and HIT serum. JAK2 inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, however, are not recommended in the treatment of VITT or HIT because of the associated thrombocytopenia and their partial action relative to the full blockade-inducing agents that target FcγRIIA, such as the monoclonal antibody, IV.3. The present findings may have significance for the ability of PF4 to inhibit megakaryopoiesis,27 which has been attributed to an interaction with low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 but with the underlying mechanism unknown.28 Further studies are required to determine the interplay of PF4 with TPO, c-Mpl, and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Simon Abrams (University of Liverpool, Liverpool, United Kingdom), Joseph E. Aslan (Oregon Health & Science University), Ian Hitchcock (University of York, York, United Kingdom), Alan Parker (University of Wales, Cardiff, United Kingdom), and Julie Rayes (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, United Kingdom) for helpful discussions. The authors thank Jinglei Ju and Todd Mize (University of Birmingham) for phosphoproteomic work, and Adam Cunningham and the late Margaret Goodall (University of Birmingham) for their guidance with IgG isolation from plasma.

This study was funded by the UK Department of Health and Social Care and supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) (NIHR135073). The NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203326) and the British Heart Foundation Accelerator (BHF) (AA/18/2/34218) have supported the Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, where this research is based. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not represent any of the listed organizations. The work was also supported through a BHF Dedicated Scholarship (R.J.B.). S.P.W. holds a BHF Chair (CH03/003).

Authorship

Contribution: R.J.B. and S.J.M. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. L.A.M. and E.M.M. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and revised the manuscript. A.S. interpreted data and revised the manuscript. S.P.W. designed the study, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. P.L.R.N. designed the study, recruited patients, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.J.B. and P.L.R.N. are named investigators on an unrelated research grant from AstraZeneca. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Phillip L. R. Nicolson and Steve P. Watson, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; email: p.nicolson@bham.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

∗R.J.B. and S.J.M. contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding authors. Mass spectrometry data are deposited to the PRoteomics IDEntifications Database (PRIDE) and are available via www.ProteomeXchange.org (identifier PXD043558).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![PF4 induces aggregation through binding to c-Mpl and activation of the JAK2-STAT3/5 pathway. (A) PF4 dose-response assessed by light transmission aggregometry. Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were stirred at 1200 rpm for 1 minute before addition of PF4. (Ai) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Aii) Quantification of aggregation (area under the curve [AUC] per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 4-13). (B) Phosphorylation of STAT3, STAT5, JAK2, and c-Mpl in PF4-stimulated platelets. Washed platelets (4 × 108/mL) were preincubated with eptifibatide (9 μM) for 10 minutes before PF4 addition. After 10 minutes, platelets were lysed. Protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and analyzed for panphosphotyrosine (4G10), phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; Tyr705), phosphorylated STAT5a/b (pSTAT5a/b; Tyr694/699), phosphorylated c-Mpl (pc-Mpl; Tyr626), and Syk. For JAK2, samples were immunoprecipitated (IP) before western blotting for panphosphotyrosine with 4G10 (pJAK2). (Bi) Representative western blots using monoclonal antibodies to phosphotyrosine (4G10) and to pSTAT3 and pSTAT5a/b. (Bii) Representative western blot using 4G10 after JAK2 IP. (Biii) Representative western blot using an antibody to pc-Mpl. (Biv) Quantification of pixel lane intensities for phosphorylation of STAT3 (dark blue triangles), STAT5 (red circles), c-Mpl (light blue diamonds), and JAK2 (green squares) measured as fold change relative to resting (n = 3). Values are normalized for loading controls. (C) Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) showing binding of PF4 to c-Mpl. C-Mpl was conjugated directly onto the chip and PF4 flowed over. All sensograms shown are double reference subtracted, and at least 2 replicates were injected per cycle with experimental replicates of n = 3. RU: response units. Statistical analyses by a 1-way analysis of variance; ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/143/1/10.1182_blood.2023020872/4/m_blood_bld-2023-020872-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1769243487&Signature=UsssePRodjRreeRbRLTORhbYFWVMcEKqbP7kGA9WODOkmcRoqyYQ3WULWM2xak56yU2rd~LOmsDNZAcSoYQE835o9JROUA4VhMZaXXbId-SdUhTGLd3cVlzN3fw08DVeFybQbyENCe4j7o9kBYJzNz9omXtecQlP~VbHql7jGmrK5PSvfp6EmvEUtyckKBDssscCyAfMe9MjRGxjgsT5q7eV7Hr4dIpeUMqsHxvpZei0Q1mP~YgpWiHkAIY0B7dapCJn~zTIHFMEritfMky~lVkAZP9yWu0VNCkCBmZtUnpFgoiS7m-mBKxnmwKFCgG7z1qpP7N4OPhC2MX0KtZrPA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![JAK2 and c-Mpl blockade inhibit platelet responses to PF4. (A) Inhibition of PF4-induced platelet aggregation with ruxolitinib (Rux). Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were incubated with Rux (100 nM) or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] 0.01%) for 5 minutes and stirred at 1200 rpm before addition of PF4 (50 μg/mL). (Ai) Representative aggregation traces to PF4 (50 μg/mL) and Rux (100 nM). (Aii) Quantification of aggregation (area under the curve [AUC] per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 8) and analyzed by a paired t-test. (B) Enhancement of platelet aggregation to CRP by PF4 and inhibition by Rux. Prewarmed platelets were incubated with Rux (100 nM) for 5 minutes, followed by PF4 (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes before CRP (0.03 μg/mL) addition. (Bi) Representative aggregation traces. (Bii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 15 minutes and analyzed by a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (C) Rux inhibits STAT3 and STAT5a/b phosphorylation induced by PF4 and TPO. Prewarmed platelets (4 × 109/mL) were preincubated with eptifibatide (9 μM) for 10 minutes, then Rux (10-100 nM) for 5 minutes before stirring for an additional minute and PF4 (50 μg/mL) or TPO (100 ng/mL) addition. After 10 minutes, platelets were lysed. Protein was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate gel electrophoresis and analyzed for panphosphotyrosine (4G10), phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3; Tyr705), phosphorylated STAT5a/b (pSTAT5a/b; Tyr694/699), phosphorylated c-Mpl (pc-Mpl; Tyr626), and Syk. (Ci) Representative western blots. (Cii-iii) Quantification of pixel lane intensities for phosphorylation of (Cii) STAT3 and (Ciii) STAT5a/b, measured as percentage change relative to resting (n = 3). Values are normalized for loading controls. (D) PF4 enhancement of platelet aggregation to IgG isolated from a patient with VITT (IgG) and inhibition by Rux. Prewarmed platelets (2 × 108/mL) at 37 °C were incubated with Rux (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO 0.01%) for 5 minutes, PF4 (10 μg/mL) or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) for 5 minutes, then stirred at 1200 rpm before IgG (100 μg/mL) addition. (Di) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Dii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 7) and analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. (E) PF4 enhancement of platelet aggregation to VITT serum (Serum) and inhibition by Rux. Platelets were prepared as for D with the addition of serum instead of IgG. (Ei) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Eii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 7) and analyzed by a 1-way ANOVA. (F) As for E but with serum from a different patient. (G) Effect of polyclonal anti–c-Mpl blocking antibody (Ab) on platelet aggregation to PF4 and PF4 + VITT IgG. (Gi-ii) Washed platelets were incubated with anti–c-Mpl antibody (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes and stirred for an additional minute before PF4 (10 μg/mL) addition. (Gi) Representative platelet aggregation traces. (Gii) Quantification of aggregation (AUC per minute) for 30 minutes (n = 6) and analyzed by a paired t-test. (Giii-iv) As for Gi-Gii but preincubated with PF4 (10 μg/mL) for 5 minutes after incubation with c-Mpl antibody before stirring and IgG addition. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/143/1/10.1182_blood.2023020872/4/m_blood_bld-2023-020872-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1769243487&Signature=Lc22IXzBp7AHVjc~rNOsU1Ibds6Dty2vdbv-QfjK87G-TPPfMHpdLZGHrs4CAddaJeRqmajQko6Zi0MR2oumcT6YHMU~9qa-d7oFaZcHSIKGoliI-Jr2lGUi3frfUYqDcNt0mLwRrotflwVbh4pnh3eGrbK6NUU93i9m~VGYPEEv8jpHp~P9reiix4fF6aR3T4HDw2i3gQGD-ol-jt81VdFt2xorEcNs8X8hmtKOj5salXLxGUGB34NwvDaobf59ouxraonXJM43LwlrAxzMBs~w8wyK0kJACCnxnRv28yQ8jDq5c4dupDn9xR~8tdpAOdElPlXu5zQJEFtK0ZJzaA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)