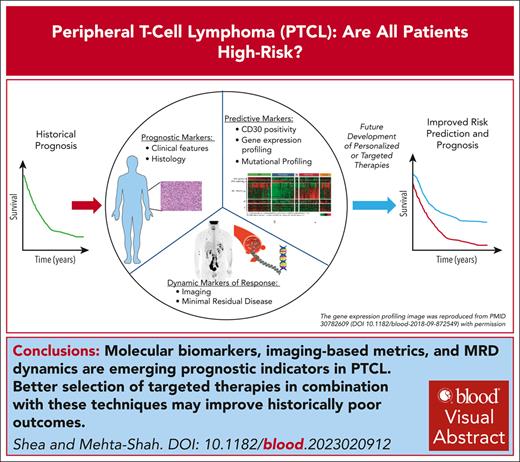

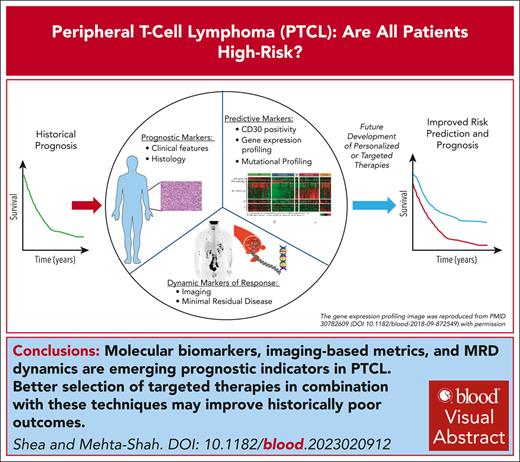

Visual Abstract

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell neoplasms that represent ∼10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Outcomes for the majority of patients with PTCL are poor, and treatment approaches have been relatively uniform using cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone–based therapy. For example, large registry studies consistently demonstrate 5-year overall survival of ∼30% to 40%. However, as our understanding of the biology underpinning the heterogeneity of PTCL improves and as treatments specifically for PTCL are developed, risk stratification has become a more relevant question. Tools including positron emission tomography–computed tomography and minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring offer the potential for dynamic risk stratification. In this review, we first summarize registry data describing outcomes in the most common subtypes of PTCL: PTCL not otherwise specified, nodal T-follicular helper cell lymphoma including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, and anaplastic large cell lymphoma. We describe current clinically based prognostic indices validated for PTCL and highlight emerging tools for prognostication including novel molecular biomarkers, imaging-based metrics, and MRD dynamics.

Introduction

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a heterogeneous group of mature T-cell neoplasms that represent ∼10% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The World Health Organization1,2 and International Consensus Classification3 identify >30 distinct T and natural killer (NK) cell lymphomas, with the most common being peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), nodal T-follicular helper (TFH) cell lymphoma including angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL).4-12 However, as our understanding of the biology underpinning the differences in PTCLs improves and with the subsequent development of treatments directed toward these rare diseases, risk stratification has become a more relevant question. This begs the question: are there T-cell lymphomas that are not quite so high risk? Tools including positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) and minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring offer the potential for dynamic risk stratification that could also improve patient outcomes. In this review, we first summarize registry data describing outcomes in PTCL subtypes and describe current clinicopathologic risk stratification tools. We highlight emerging prognostic and potentially predictive tools, including novel molecular biomarkers, imaging-based metrics, and MRD dynamics.

Prognostic information from T-cell registry data

The overall poor prognosis of patients with PTCL has been demonstrated in several large national and international registry studies and multi-institutional retrospective studies4-10,13 (Table 1), with the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) ranging from 20% to 30% and 5-year OS ranging from 30% to 40%. The exception to this is ALCL expressing the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) protein, which has been proven to be more chemosensitive, with 5- year PFS and OS of 60% and 70%, respectively.5-10,14,15 ALK-positive ALCL is characterized by a younger median age at diagnosis and more favorable distribution of International Prognostic Index (IPI) risk factors.12,14,16 A retrospective analysis of patients with ALCL treated on frontline clinical trials showed that although patients with ALK-positive ALCL had superior PFS and OS relative to those with ALK-negative ALCL, only age and β2 microglobulin levels, and not ALK status, predicted PFS and OS on multivariate analysis.16 Therefore, the favorable prognostic impact of ALK positivity may, in part, be due to its association with other known prognostic factors such as age. The better prognosis for patients with ALCL (both ALK positive and negative) has been further accentuated by the development of brentuximab vedotin (BV)-containing frontline chemotherapy regimens that are particularly effective in this population.17

Current registry data are often not fully representative of all patients with these rare disorders. Patients who are very ill at the time of diagnosis or have limited remaining tumor sample may not be enrolled to such efforts because of tissue requirements or eligibility criteria.4,7,13 Despite these limitations, it is humbling that the outcomes of patients with PTCL, as demonstrated through both US and international registries, have been similar. Current and future registry studies will help us better understand the prognosis of patients after the adoption of BV in frontline therapy, refinement of classification for TFH phenotype lymphomas, and the impact of social determinants of health on prognosis18 (NCT04996706).19,20

Clinical prognostic scoring systems

There have been multiple attempts to identify populations within T-cell lymphoma that are at particularly high and low risk by using prognostic indices based on clinical factors. One of the earliest prognostic scoring systems applied to PTCL-NOS was the IPI, which was originally designed to predict OS in patients with aggressive NHL (both T- and B-cell NHLs) treated with anthracycline-containing chemoimmunotherapy (Table 2).21,25 In an analysis of 340 patients from the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project, the 5-year OS was 50% for those with low-risk (0-1 risk factors) IPI scores vs 11% for those with high-risk (4-5 risk factors) IPI scores.21 Several other prognostic scoring systems were developed to predict both PFS and OS for patients with newly diagnosed PTCL-NOS.10,22-24 The Prognostic Index for T-cell Lymphoma (PIT)22 and the T-cell Score10 included only patients with PTCL-NOS in data sets used for derivation, whereas the modified PIT23 and the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project score24 included both PTCL-NOS and AITL. All of these use similar variables (Table 2), including clinical parameters (age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status [ECOG PS], and stage) and laboratory data (lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], absolute neutrophil count, and platelet count). The modified PIT also includes a histologic variable (Ki67).23 In a comparative analysis of 4 of these scoring systems (including several additional subtypes of PTCL in addition to PTCL-NOS), all were similarly able to predict PFS and OS among treatment-naïve patients with PTCL. Of note, even in the lowest-risk groups (in all 4 scoring systems), long-term PFS was <30%.26

Although patients with ALCL were not included in data sets used to construct the aforementioned prognostic scoring systems, an analysis of 235 patients with ALK-negative ALCL from the International T-cell Project showed that both the IPI and the PIT were able to predict PFS and OS in this population. Five-year PFS and OS were 51% and 60%, respectively, for those with low-risk (0-1 risk factors) PIT vs 21% and 24%, respectively, for those with high-risk (2-4 risk factors) PIT.9 In multivariate analysis, the presence of B symptoms, elevated LDH, ECOG PS ≥2, and platelet count <150 × 109/L were associated with inferior OS whereas the presence of B symptoms, elevated LDH level, and ECOG PS ≥2 were associated with inferior PFS.

Similarly, analysis of the 131 patients with ALK-positive ALCL enrolled in the International T-cell Project confirmed the ability of the IPI and PIT to predict prognosis in this subtype of PTCL. Five-year OS was 75% for those with low-risk (0-1 risk factors) PIT vs 43% for those with high-risk (2-4 risk factors) PIT. On multivariate analysis, elevated LDH level and ECOG PS ≥2 predicted inferior OS whereas elevated LDH level, ECOG PS ≥2, and stage III to IV disease predicted inferior PFS.14 Interestingly, the differences in outcome for those who have ALK-positive vs ALK-negative ALCL are not as pronounced when matched for clinical risk factors. An analysis of the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project showed that the 5-year OS by low (0-1 risk factors), low-intermediate (2 risk factors), high-intermediate (3 risk factors), and high-risk (4-5 risk factors) IPI in ALK-positive and ALK-negative ALCL were 90% vs 74%, 68% vs 62%, 23% vs 31%, and 33% vs 13%, respectively.27

Given the unique clinicopathologic features of AITL, 2 analyses were performed from separate international registries to risk stratify this subset of patients with PTCL. The Prognostic Index for AITL includes age of >60 years, ECOG PS ≥2, extranodal sites >1, B symptoms, and platelets <150 × 109/L stratified patients into low-risk (0-1 risk factors, 30% of patients) and high-risk (≥2 risk factors, 70% of patients) groups with 5-year OS of 44% vs 24%, respectively.15 The AITL score includes age of ≥60 years, ECOG PS >2, and elevated β2 microglobulin and elevated C-reactive protein levels, dividing patients into low- (0-1 risk factors, 17%), intermediate- (2 risk factors, 23%), and high- (3-4 risk factors, 60%) risk groups, with 5-year OS of 63% (low risk), 54% (intermediate risk), and 21% (high risk).8

Clinical prognostic scoring systems have been developed for several rare T-cell NHL subtypes but are not currently used to guide therapeutic decision making. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) is divided into acute, lymphoma, chronic, and smoldering subtypes that differ in clinical manifestations and prognosis.28 Outcomes for all subtypes are poor, with 4-year OS of 11% (acute), 16% (lymphoma), 36% (chronic), and 52% (smoldering) in a large retrospective series (n = 1594).2 Several prognostic scoring systems have been developed for aggressive (acute and lymphoma-type) ATLL2,29,30; and the IPI has been shown to predict outcomes in this patient population.31 In a retrospective analysis of patients with chronic and smoldering ATLL, only soluble interleukin-2 receptor level retained prognostic significance on multivariate analysis, with 4-year OS of 78%, 56%, and 26% in patients with low, intermediate, and high soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels, respectively.32 ATLL is frequently characterized by cutaneous involvement, and skin tumors and erythrodermic eruptions are associated with dismal prognosis (5-year OS 0%, vs ≥40% in those with other cutaneous manifestations).33-35

In extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, the Prognostic Index of NK Lymphoma score predicts OS and PFS of patients treated with nonanthracycline-based chemotherapy.36 Risk factors consist of age of >60 years, stage III or IV disease, distant lymph node involvement, and nonnasal disease, with 3-year OS ranging from 81% (0-1 risk factors) to 25% (≥2 risk factors). Several other prognostic scoring systems have been derived with patients largely treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy with or without radiation37,38; another scoring system was more recently validated for patients treated with nonanthracycline-based chemotherapy.39 Peripheral blood Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA was assessable in a subset of the cohort used to derive the Prognostic Index of NK Lymphoma index and was independently associated with PFS and OS. Importantly, interim positivity for EBV DNA was independently associated with inferior OS in patients with NK/T-cell lymphoma treated with asparaginase-based chemotherapy, whereas baseline EBV titers were not.40 Interim PET–CT was also an independent predictor of PFS in a small prospective study.41 Similarly, PET positivity and detectable EBV DNA at end-of-treatment assessment are associated with inferior PFS and OS.42

Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma are rare subtypes of extranodal T-cell lymphoma with an overall poor prognosis, with a median OS of 7 to 10 months.5,43,44 The PIT and IPI show variable prognostic power in these diseases.5,43,44 In enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, the presence of B symptoms has been associated with a particularly poor prognosis (2-year OS of 0% in 1 retrospective series).43 A prognostic scoring system incorporating the presence of B symptoms in addition to the IPI variables was better able to risk stratify patients. Patient at high risk (presence of B symptoms, regardless of IPI score) had a median OS of 2 months, those at intermediate risk (no B symptoms with an IPI score ≥2) had a median OS of 7 months, and patients at low risk (no B symptoms with an IPI score of 0 or 1) had a median OS of 34 months.43

Molecular prognostic factors

Better understanding of PTCL molecular complexity has not only led to refinement in PTCL classification but has also highlighted important implications on prognosis. In a landmark analysis, Iqbal et al performed gene expression profiling (GEP) on 372 pretreatment PTCL samples.45 Among the 121 cases of PTCL-NOS, unsupervised hierarchical clustering revealed 2 groups of patients, 1 characterized by increased expression of GATA3 and its target genes (GATA3 subgroup) and the other with increased expression of TBX21 and associated genes (TBX21 subgroup). GATA3 and TBX21 are thought to be master regulators of T helper cell type 2 and T helper cell type 1 differentiation and function, respectively, suggesting different cells of origin for these subtypes of PTCL-NOS. The GATA3 subgroup had inferior 5-year OS relative to the TBX21 subgroup (19% vs 38%). Within the TBX21 subgroup, those with increased expression of cytotoxic T-cell associated genes had inferior prognosis, with 5-year overall survival less than 20%, vs ∼50% for TBX21 subgroup cases lacking the cytotoxic T-cell signature.45 An immunohistochemistry-based algorithm distinguishing GATA3 and TBX21 subtypes of PTCL-NOS showed that both high IPI score and GATA3 subtype were independently associated with inferior OS.46 The GATA3 subgroup recurrently has alterations in the tumor suppressors CDKN2A/B and TP53, deletion in PTEN, and activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. In contrast, the TBX21 subgroup showed lower genomic complexity, more frequent alterations in epigenetic regulators including TET2, and activation of the NF-κB pathway.47,48 Cases belonging to the TBX21 subgroup were also characterized by a mixed inflammatory tumor microenvironment.48 If validated, such refined molecular classification of PTCL-NOS has the potential to be not only prognostic but also predictive, suggesting the potential for differential sensitivity to various therapeutics (PI3K inhibitors in the GATA3 subset, epigenetic-based therapies in the TBX21 subset, etc).

As has been observed in several hematologic malignancies, alterations in TP53 have been associated with inferior prognosis in PTCL. In a single-institution study of 132 patients with PTCL treated with frontline cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP)-based therapy, TP53 mutations occurred in 28% of patients with PTCL-NOS, but TP53/chromosome 17p deletions were uncommon.49 The frequency of TP53 mutation varied based on histology, occurring in only 3% of patients with AITL. TP53 mutations were associated with inferior 2-year PFS, 10% in TP53-mutated PTCL vs 32% in TP53 unmutated PTCL. There was no difference in OS between patients with and those without TP53 mutation. They also observed that patients with CDKN2A deletion (n = 9; 7%) had a median OS of 17.6 months vs 56.7 months in those lacking this alteration.49 These novel findings should be further validated in prospective, multi-institution studies.

AITL and other TFH phenotype lymphomas are enriched for mutations in epigenetic regulators.50-52 Additionally, in AITL, expression of a B-cell–related gene signature was associated with superior OS in independent analyses.45,48,52 Whether this observation will hold true for other TFH cell lymphomas remains to be seen.

In patients with ALK-negative ALCL, additional cytogenetic changes have prognostic significance. Rearrangement of the DUSP22 gene, detected in 19% to 30% of ALK-negative ALCL, is a favorable prognostic indicator, whereas rearrangement of the TP63 gene, detected in 2% to 8% of ALK-negative ALCL, portends a poor prognosis.53-55 The 5-year OS was 85% for ALK-positive ALCL, 90% for DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL, 17% for TP63-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL, and 42% for ALK-negative ALCL lacking DUSP22 or TP63 rearrangements.53 GEP revealed that DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL may be biologically distinct, characterized by lack of STAT3 activation and inactivity of the programmed cell death protein 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint.56 Although autologous transplantation consolidation in first remission is frequently considered in ALK-negative ALCL,5,57,58 1 series showed a 5-year OS of 87% for DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL treated with anthracycline-based induction without transplantation consolidation.54 Of note, the favorable prognostic implications of DUSP22 rearrangements were not as pronounced in other relatively large series in which the 5-year PFS and 5-year OS for DUSP22-rearranged ALK-negative ALCL was 40% to 57% and 40% to 67%, respectively.54,55,59-61

Increasing understanding of recurrent molecular alterations is also helping refine prognostication in ATLL. In an analysis of >400 patients, aggressive (acute and lymphoma-type) ATLL was characterized by a higher frequency of mutations and copy-number alterations, particularly IRF4 mutations and CDKN2A, CCDC7, and GPR183 deletions, whereas STAT3 mutations were more common in indolent (smoldering and chronic) ATLL.62 In aggressive ATLL, PRKCB mutation, PD-L1 amplification, age of ≥70 years, and Japanese Clinical Oncology Group prognostic index (poor performance status and/or elevated calcium level) were independently associated with shorter OS. In indolent ATLL, IFR4 mutation, CDKN2A deletion, and PD-L1 amplification predicted inferior OS. Molecular characterization was particularly helpful in risk stratifying patients to the unfavorable chronic subgroup of indolent ATLL, for which the 3-year OS was 31% for patients with 1 of the aforementioned molecular alterations vs 67% for those without.48,62

Using traditional histopathologic diagnostic tools, studies have shown that the diagnosis of PTCL histopathologic subtype is changed in nearly 1 in 4 cases when reviewed at an expert academic center.63 Given that establishing the diagnosis of PTCL can be challenging, one could imagine that artificial intelligence–based diagnostic platforms that integrate GEP, mutational profiling, and histology would aid in diagnosis and patient care and be cost effective in under-resourced areas.64 Such efforts are ongoing for other solid tumors as well.65-67 Although not yet established in PTCL, machine learning represents a promising area of future investigation for diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive tools.

Imaging modalities to risk stratify patients

Although multiomic approaches to delineate risk in PTCL have been helping us better understand the biology of these diseases, in current clinical practice, responsiveness to chemotherapy has been the most useful tool in identifying high-risk populations. This is evidenced by the fact that progression of disease within 24 months of diagnosis has been identified as a powerful prognostic factor, with a 5-year OS of only 6% for those with progression of disease within 24 months of diagnosis vs 63% for those without.8 In the era of the Lugano and response evaluation criteria in lymphoma criteria, interim PET–CT has been demonstrated to be predictive of outcomes in PTCL in 2 large series.68 In a single-center retrospective study of 99 patients with PTCL treated with CHOP-like chemotherapy with intent to pursue consolidative treatment with autologous stem cell transplantation, a positive interim PET by the Lugano criteria predicted for a worse event-free survival and OS (hazard ratio, 3.57; P < .001).69 In this series, 16% of patients had a positive interim PET scan and 84% had a negative interim PET by the Lugano criteria. At 4 years, the OS and PFS in the interim PET-negative group were 83% and 58%, respectively, compared with 0 for the interim PET-positive group. In a separate study, interim PET by the Lugano criteria in 140 patients with PTCL, PET-CTs after 2 cycles (n = 43) and after 4 cycles (n = 95) was examined.70 Patients with a positive interim PET–CT after 2 or 4 cycles had a 2-year OS of 22% and 32%, respectively. Patients with a negative result with PET-CT after 2 or 4 cycles had a 2-year OS of 84% and 85%, respectively (Table 3). These studies demonstrate that positive interim PET–CT by the Lugano criteria is an indicator of poor prognosis. Conversely, the prognosis for those who achieve a complete remission at their interim PET is more favorable. Although these findings are of considerable interest, they should be validated in prospective studies as well.

Additionally, measures to assess the burden of baseline disease such as total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) have also been studied in PTCL. In a retrospective study of 108 patients with PTCL treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy, high TMTV, defined as TMTV >230 cm3, independently predicted worse PFS and OS.71 Those with high TMTV had a 2-year PFS of 26% compared with 60% for those with low TMTV. In a separate study of 99 patients with PTCL, high baseline TMTV, defined as >125 cm3, was associated with significantly worse OS (5 year: OS 63% vs 90%; hazard ratio, 6.025; P = .022; Table 3).69

The combination of PET response and baseline TMTV may have a higher predictive value than either individual parameter. In a retrospective analysis of 140 patients with PTCL, a positive interim and end-of-treatment PET were predictive of significantly worse outcomes.70 Those with a positive interim PET after 2 cycles had a 2-year PFS of 6% compared with 73% in patients with a negative interim PET. Interim PET after 3 or 4 cycles carried a positive predictive value for PFS of 69%. A model combining the baseline TMTV and interim PET was able to further risk stratify patients into 4 subgroups with 2-year PFS ranging from 79% to 0%.70

Another retrospective study of 63 patients with nodal PTCL who had a baseline and interim PET–CT found that high baseline total lesion glycolysis, calculated by multiplying the MTV and the mean standardized uptake values, independently predicted poorer survival.72 Similarly, in a study of 51 patients with PTCL, baseline TMTV and total lesion glycolysis independently predicted PFS and OS in a multivariate analysis and could add to prognostication based on clinical risk factors.73 Therefore, models combining baseline imaging to identify those with lower burden of disease with interim response assessment can identify a subset who have the best prognosis in PTCL.

Interim PET–CT could serve as a clinically relevant tool in PTCL to differentiate which patients could benefit from consolidative transplant strategies or are unlikely to benefit from continued anthracycline-based chemotherapy. Efforts to validate the aforementioned findings are ongoing in the setting of prospective frontline PTCL studies (NCT04803201). Based on these initial series, patients who have complete remission by PET on interim evaluation, and low baseline tumor burden seem to have favorable prognosis. However, these studies were performed in retrospective series and should be validated in prospective cohorts.

MRD techniques

Techniques to quantify MRD in hematologic malignancies have been rapidly improving and are being applied as prognostic and predictive tools in some clinical trials in lymphoma. However, in T-cell lymphomas, applications of MRD are still exploratory. One approach for evaluation of MRD is tracking of the T-cell receptor (TCR). Given that each T-cell lymphoma should have a unique TCR β and γ genetic sequence, identification and quantification of the unique TCR clonotype in the peripheral blood has been investigated as a tool for MRD monitoring. In a prospective study of 41 patients, TCR clonotype was identified in the tumor tissue and then assessed in the peripheral blood at the end of treatment. Unfortunately, at the end of treatment, 80% of patients had a positive TCR clonotype identified in the peripheral blood and this was not associated with complete remission by PET. PFS and OS at 18 months did not differ between those who had TCR MRD-positive or -negative statuses at the end of treatment (OS 64% vs 67%, P = .63; PFS 41% vs 50%, P = .40).74 Interestingly, in this series, 4 patients who underwent consolidative transplant had undetectable TCR in the peripheral blood after transplant, and none relapsed at a median follow-up of 32 months after transplant.75 This observation warrants further study regarding whether posttransplant TCR MRD testing can identify a better risk prognostic group.

Similarly, in a series of 34 patients treated with etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin for PTCL and had an identifiable clonotype at baseline, 11 of 23 (46%) had a detectable TCR clonotype in the blood at the end of treatment. Interestingly, in this series, patients who had undetectable MRD had a trend toward better PFS and OS than those who had detectable disease in the peripheral blood.76

Other MRD techniques to better risk stratify patients with PTCL are currently ongoing, including using error-corrected sequencing mutational profiling. In a single-center prospective study, the mutational profile from plasma cell-free DNA (cf-DNA) and tumor tissue was compared for patients with newly diagnosed T-cell lymphoma and showed high concordance. Trends in cf-DNA correlated with imaging-based response assessments and higher baseline cf-DNA levels were associated with inferior PFS and OS. Follow-up was relatively short in this cohort, and whether end-of-treatment cf-DNA negativity predicts long-term prognosis is an important question for further study.77 Therefore, efforts to understand how to use MRD assays in PTCL are currently exploratory but of considerable interest to the field.

Implications of therapy on prognosis

Although risk stratification has generally been based on clinical parameters in T-cell lymphoma, these have not been influential in guiding treatment, and personalized therapy has been lagging. However, biomarker-driven strategies that are beginning to make some of these lymphomas less high risk have started to move the needle in T-cell lymphomas. The most notable example is the addition of BV to frontline therapy in ALCL. BV is a CD30 monoclonal antibody–drug conjugate linked to monomethyl auristatin E, which inhibits microtubules. The landmark study, ECHELON-2 was a 452-patient international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study comparing BV combined with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CHP) with CHOP for patients with PTCL who had ≥10% CD30 by immunohistochemistry and demonstrated both an improvement in PFS and OS.17 Those treated with BV-CHP demonstrated estimated 5-year PFS and OS of 51% and 71%, respectively, compared with 43% and 61%, respectively, with CHOP.78 Of note, 70% of the patients in this study had ALCL and the improvement in outcomes with BV-CHP was evident only in the ALCL subtype. Although the study was not powered to evaluate the efficacy of other subtypes, in the 54 patients with AITL and 72 with PTCL-NOS, no significant difference in PFS or OS was observed with BV-based therapy. Therefore, the development of BV-CHP in ALCL has led to both ALK-negative and ALK-positive ALCL becoming less high risk.

Similarly, there is increasing evidence that the unique biology of TFH-driven PTCL (including AITL, TFH lymphoma, and PTCL of TFH phenotype) is particularly sensitive to agents targeting the epigenome. Studies of histone deacetylase inhibitors, both as single agents and in combination, have shown higher response rates in AITL, suggesting that incorporation of these agents preferentially in TFH histologies79 could similarly lead to improved outcomes.80-83 Small studies combining romidepsin with duvelisib (overall response rate [ORR], 68%; n = 19),80 lenalidomide (ORR, 100%; n = 7),81 azacitidine (ORR, 100%; n = 3),82 or gemcitabine/oxaliplatin (ORR, 100%; n = 6)83 have all shown high response rates in AITL. Similarly, in the ORACLE study evaluating oral azacitidine in TFH neoplasms, ORR was 33% but there was a trend of PFS and OS benefit in those treated with azacitidine over investigator’s choice.84 Oral azacitidine plus CHOP was evaluated in an exploratory phase 2 study (n = 20) with mostly patients with PTCL-TFH, and demonstrated high ORR and a complete remission rate of 75%.85 Similarly, duvelisib, a PI3K inhibitor, reportedly showed greater benefit in AITL, with an ORR of 67%, compared with 48% in PTCL-NOS and 13% in ALCL.86 Combinations incorporating duvelisib and oral azacitidine with CHOP-based therapy are currently being evaluated in the US Intergroup randomized study ALLIANCE A051902, in CD30-negative PTCL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04803201).

Conclusions

Outcomes for the majority of patients with PTCL, with the exception of ALK-positive ALCL, unfortunately remain poor. Although many clinical scoring systems have been developed to help predict outcomes (Table 2), these have overall not been useful in guiding therapeutic decisions.8 To date, response to therapy, whether evaluated clinically or using imaging, is most telling of prognosis. However, increasing understanding of the molecular mechanisms of PTCL has facilitated development of novel targeted therapies. As evidenced by ECHELON-2, this offers the hope that in the future, we may move beyond a “one size fits all” approach to the selection of therapy based on molecular biomarkers. Ongoing clinical trials testing incorporation of novel agents into frontline therapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04803201) will provide important data to guide future research and practice. Collaborative research efforts are ongoing to develop tools to identify patients at high risk earlier in their treatment course, including baseline PET parameters, interim PET analysis, and MRD monitoring. We are hopeful that with continued research and collaboration, we will incrementally shift survival curves for PTCL. Therefore, although markers of responsiveness to therapy, as well as brentuximab-based strategies for ALCL, have started to delineate a group of patients with lower risk, the majority of patients remain at higher risk. Nevertheless, high risk is only meaningful in the context of available treatments, and with better treatments and better understanding of who benefits most from these therapies, we are hopeful that the outcomes for patients with PTCL will be better in the future.

Acknowledgment

N.M.-S. is a scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia Lymphoma Society.

Authorship

Contribution: N.M.-S. and L.S. performed the research, and designed and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.M.-S. has received institutional clinical trial funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, C4 Therapeutics, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo, Genentech/Roche, Innate Pharmaceuticals, Secura Bio/Verastem, Yingli Pharmaceuticals, and Dizal Pharmaceuticals; and has received compensation for service as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Secura Bio/Verastem, Daiichi Sankyo, C4 Therapeutics, Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin. L.S. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Neha Mehta-Shah, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid, Box 8056, St. Louis, MO 63110; email: mehta-n@wustl.edu.