Abstract

Because of its anticarcinogenic and antimutagenic properties, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) has been proposed for cancer treatment. Here we present a mechanism of action for NAC in cancer. Our data show that NAC (1) induces an early and sustained increase of membrane tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) expression on human stimulated-peripheral blood (PB) T cells and (2) increases membrane TNF-RI and TNF-RII on tumoral cell lines and on T cells after stimulation. These effects result from an early inhibition of both TNFα and TNF-R shedding, as well as a later increase of the respective mRNA expression. Consequently, NAC confers cytotoxic properties to human PB T cells through a membrane TNFα-dependent pathway. In vivo, NAC given orally inhibits tumor appearance in more than a third (18 out of 50) B6D2F1 mice injected with L1210 lymphoma cells. Spleen cells from protected mice killed L1210 lymphoma cells in vitro in a membrane TNFα-dependent manner. Furthemore these mice were resistant to a second inoculation of L1210 cells without further treatment with NAC. Thus, NAC exhibits a potent antitumoral activity by modulating TNFα and TNF-R processing without showing any in vitro and in vivo toxicity.

N-ACETYL-L-CYSTEINE (NAC) is a thiol antioxidant precursor of glutathione (GSH) used in human therapy usually as a mucolytic agent.1 Intracellular GSH is involved in numerous metabolic pathways including cell protection against oxidative injury2 and alkylating agents.3 These thiols appear as promising drugs in cancer prevention as they present antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic properties,4 and they also limit tumor invasion and metastasis.5 In vitro NAC and GSH synergize with different stimuli in increasing proliferation, interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, and CD25 expression by T cells.6,7 They also increase the cytotoxic properties of lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) and natural killer (NK) cells through pathways dependent on IL-2 production and on GSH neosynthesis.8-10 However, the mechanisms involved remain undefined.

TNFα is a pleiotropic cytokine expressed as a membrane or as a soluble protein11 by several cell types including T cells.12 Soluble tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (17 kD) results from the shedding of the membrane form (25 kD) mediated by a Zn++-dependent endopeptidase.13-15 In addition to the potent proinflammatory properties of the soluble form,16-18 membrane and soluble TNFα mediate cell death19,20 and are crucial to initiate an antitumoral response. TNFα-induced signaling is mediated by two receptors, TNF-RI (or p55) and TNF-RII (or p75). Soluble TNF-R, generated by the shedding of the membrane forms,21 22 neutralize the activity of TNFα by inhibiting its binding to the membrane receptors. Thus, several studies are focused on the modulation of TNFα and TNF-R processing in view of increasing the efficiency of antitumoral responses. In this study, we analyzed the effects of NAC on TNFα and TNF-R processing and on TNFα-dependent T-cell cytotoxicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.NAC, captopril, L-cysteine, D-cysteine, L-carnithine, catalase, superoxyde dismutase (SOD), S-methylcysteine (SMC), desferrioxamine, reduced-GSH and oxidized-glutathione (GS-SG), D-penicillamine, and vitamin C were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Dithiothreitol (DTT) and mercapto-propionic acid (MPA) were purchased from Aldrich (Buchs, Switzerland). Compounds were dissolved in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Basel, Switzerland) and adjusted to pH 6.5 before use.

Purification and stimulation of human T lymphocytes.Peripheral blood (PB) T cells were purified by rosetting with sheep red blood cells. The purity, determined with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-human CD3 monoclonal antibody (MoAb; Becton Dickinson, Erembodegem, Belgium) using a FACStar plus cytofluorometer (Becton Dickinson), was greater than 95%. T cells (2 × 106/mL) were cultured in culture medium consisting of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Life Technologies), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 2 mmol/L sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 50 U/mL penicilin (Life technologies). T cells were stimulated from 2 to 96 hours with 1 μmol/L ionomycin (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), immobilized anti-CD3, and/or anti-CD28 MoAb (10 μg/mL; Immunotech, Marseille Luminy, France) with or without 10 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Calbiochem) in the presence or not of the compounds tested.

Cell-surface labeling.Expression of human membrane TNFα, TNF-RI and RII, and mouse membrane TNFα was evaluated using specific rabbit polyclonal Ab (Serotec, Kidlington, UK and Becton Dickinson) detected by a FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) Ab (Morwell Diagnostics, Zurich, Switzerland). Control Ab was purified rabbit IgG (Sigma). In some experiments 100 μmol/L L-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine (BSO; Sigma), an inhibitor of GSH neosynthesis, was added 4 hours before stimulation.23 Results were expressed either as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after subtraction of the MFI obtained with the control or as a percent of MFI increase defined as follows:

where A and B are the MFI values (determined after subtraction of the MFI obtained with the control Ab) obtained with T cells stimulated with and without the compound tested, respectively.

Quantification of soluble human TNFα and TNF-RII.Soluble TNFα and TNF-RII (sTNF-RII) were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in the supernatants of T cells stimulated from 2 to 72 hours in the presence or not of NAC (Innogenetics, Zwijnaarde, Belgium, sensitivity of 4 pg/mL and R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, sensitivity of 0.5 pg/mL, respectively). sTNF-RII was expressed in pg/mL. Soluble TNFα was expressed in percent of increase or decrease of production determined as follows:

where S and R are the concentrations of TNFα produced by T cells stimulated in the presence or not of NAC, respectively.

Analysis of TNFα and TNF-RII mRNA expression by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).Stimulated-T cells were resuspended in 1 mL of Trizol reagent (Life Technologies). After extraction with chloroform, total RNA was precipitated by isopropylic alcohol. The single strand cDNA were synthetized using 5 μg of total RNA by reverse transcription with oligo-dT primers (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden). PCR amplification was performed as previously described24 with an amount of cDNA corresponding to 25 ng of starting total RNA (25 cycles; 30 seconds at 94°C; 1 minute at 60°C and 1 minute at 72°C followed by a final extension at 72°C for 4 minutes). The sequences of the specific oligonucleotides were 5′-CCTTGGTCTGGTAGGAGACG-3′ and 5′CAGAGGGAAGAGTTCCCCAG-3′ for TNFα; 5′-ATGGCGCCCGTCGCCGTCTGGGC-3′ and 5′-GATTGTGGGTTGACAGCCTTG-3′ for TNF-RII; 5′-CATGGATGATGATATCGCCG-3′ and 5′-GCTGGAAGGTGGACAGCGAG-3′ for β-actin. The PCR products were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel by electrophoresis in the presence of ethidium bromide.

In vitro cytotoxic assay against tumoral cells.Human PB T cells, stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin with or without 0.5 to 20 mmol/L NAC, were fixed for 10 minutes with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) to prevent the involvement of cytotoxic pathways other than membrane TNFα, such as soluble TNFα or perforin. The TNFα-sensitive HL60 cells in a resting state (1 × 105 cells/mL, 50 μL/well; ATCC, Rockville, MD) were incubated for 24 hours in culture medium with PFA-fixed T cells at different effector-to-target cell ratios in 96-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) in the presence or not of 20 mmol/L NAC. Cell death was measured by a MTT reduction assay.25 For neutralization assays, 106/mL PFA-fixed T cells were incubated for 2 hours with neutralizing anti-TNFα MoAb (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA or Sigma) or with a control MoAb (Sigma; 100 ng/mL). Results were expressed as a percentage of cytotoxicity defined as follows:

where S and R are the optical density (OD) values obtained with stimulated and nonstimulated T cells, respectively.

Effect of NAC on mouse cytolytic T lymphocyte activity.Cytolytic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay was performed as previously described.26 Briefly, CTL clone PbCSQB7.3.2 was isolated by limiting cloning from a BALB/c mouse immunized with the H-2Kd restricted peptide Plasmodium berghei (Pb) circumsporozoite (CS) 252-260. Cloned cells were maintained in continuous culture by weekly stimulation with peptide pulsed and irradiated P815 cells and irradiated BALB/c spleen cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 5% EL-4 supernatant as a source of IL-2 (30 U/mL). For the cytolytic assay, 1 × 106 tumor P815 cells were labeled with 100 μCi sodium (51Cr) chromate for 1 hour at 37°C and washed three times before exposition to 1 μmol/L peptide PbCS 252-260 during 15 minutes at room temperature. CTL clones, exposed or not to various concentrations of NAC, were washed twice and threefold dilutions of these cells were added to 2 × 103 51Cr-labeled target cells. After 6 hours incubation, the supernatants were harvested for counting. The results were expressed as a percentage of specific lysis determined as follows:

Effect of NAC on tumor development in vivo.B6D2F1 mice (H-2b/H-2d; IFFA-CREDO, Les Oncins, France) were injected intraperitoneally with 5 × 106 L1210 cells (H-2d; ATCC)27 and half then received NAC ad libidum in the drinking water (5 g/L) for 11 consecutive days. The solution of NAC was adjusted to pH 6.5 and changed every day. In a preliminary study, 10 mice that did not receive L1210 cells were treated orally with 5 g/L for 15 consecutive days. NAC was not toxic as assessed by macroscopic observation and autopsy at day 15. To analyze the effect of NAC, the following experiments were performed:

Fifty mice were killed on day 11 to weigh the peritoneal tumors.

Ten mice were killed at days 5, 7, 9, and 11 to evaluate membrane TNFα expression on spleen and tumoral cells, determine the frequency of T cells infiltrating the tumors, and measure the ability of the spleen cells to kill in vitro L1210 cells. Membrane TNFα expression was evaluated by FACS analysis using a rabbit anti-mouse TNFα Ab detected by a FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG Ab (Morwell diagnostics). Murine T cells were detected using a FITC-labeled rat anti-mouse CD3 MoAb (Serotec). The cytotoxic assay was performed as follows: spleen cells were fixed with PFA and incubated with L1210 cells (1 × 105 cells/mL; 50 μL/well) at different effector-to-target cell ratio in 96-well plates with or without a neutralizing rabbit purified IgG anti-mouse TNFα Ab or purified control rabbit IgG (both from Genzyme; 1 μg/mL). Cell death was measured by a MTT reduction assay.

The survival of 50 mice was determined. The eighteen out of 50 NAC-treated mice, which were still alive at day 18, were then reinjected with 5 × 106 L1210 cells without further treatment with NAC.

Statistical analysis.Statistical analysis were performed using Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

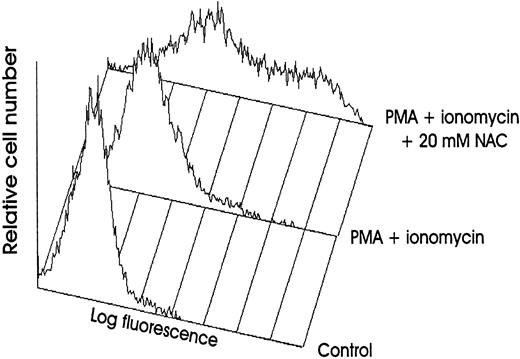

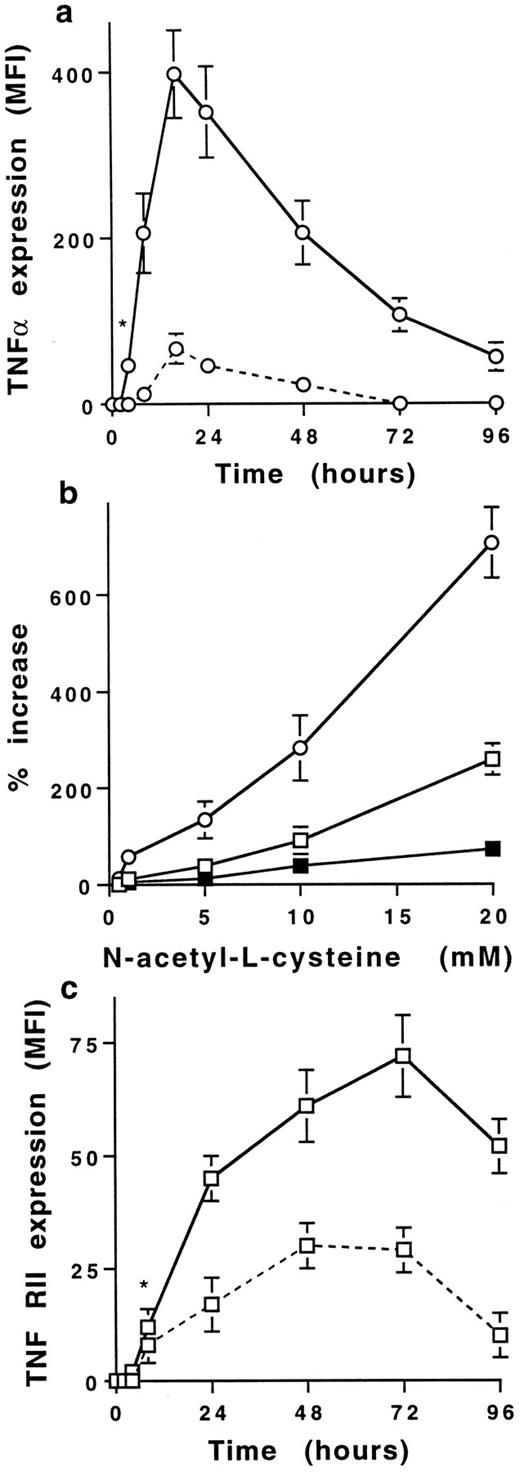

NAC increases membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression on human stimulated T cells.Stimulation of PB T cells with PMA plus ionomycin induced membrane TNFα expression, detectable from 8 to 48 hours with a maximum at 16 hours (MFI = 53 ± 5, mean ± SD, n = 6) (Figs 1 and 2a). NAC induced a dose-dependent increase of membrane TNFα expression on 16-hour-stimulated T cells; the increase was significant with 1 mmol/L (68 ± 34% increase) and maximal with 20 mmol/L NAC (706 ± 112% increase; Fig 2b). This increase was significant from 4 to 96 hours (Fig 2b) and was similar on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (725 ± 78% and 642 ± 86%, respectively, with 20 mmol/L NAC, mean ± SD, n = 6). As previously reported,21 22 TNF-RI was poorly expressed on stimulated T cells (MFI = 8 ± 2 at 48 hours) in contrast to TNF-RII (MFI = 27 ± 4 at 48 hours, mean ±SD, n = 6; Fig 2c). NAC increased in a dose-dependent manner TNF-RII expression and, to a lesser extent, TNF-RI expression (280 ± 75% and 72 ± 19% increase with 20 mmol/L NAC, respectively, mean ± SD, n = 6) on T cells stimulated by PMA plus ionomycin for 48 hours (Fig 2b). The increase of membrane TNF-RII expression was significant from 24 to 72 hours in the presence of 20 mmol/L NAC (P < .01; Fig 2c). The effect of NAC on TNFα and TNF-R expression required a stimulation including PMA (ie, PMA plus ionomycin or PMA plus anti-CD3 MoAb) as no effect was observed on T cells either unstimulated or stimulated with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 MoAbs (data not shown). Whatever the time-point and the stimulus used, the membrane expression of other molecules such as IL-1α, CD3, CD16, CD27, CD29, and CD58 was not affected by NAC (data not shown).

NAC increases membrane TNFα expression on human stimulated T cells. Membrane TNFα expression was determined by FACS analysis on human PB T cells unstimulated or stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin without or with 20 mmol/L NAC.

NAC increases membrane TNFα expression on human stimulated T cells. Membrane TNFα expression was determined by FACS analysis on human PB T cells unstimulated or stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin without or with 20 mmol/L NAC.

NAC increases in a dose- and time-dependent manner membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression on human T cells. (a) Time-dependent increase of membrane TNFα expression on T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 20 mmol/L NAC. Results are expressed in MFI values (mean ± SD, n = 6). *Means P < .01. (b) NAC induces a dose-dependent increase of membrane TNFα (○), TNF-RI (▪), and TNF-RII (□) expression on T cells stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin. Results are expressed in percent of increase (mean ± SD, n = 6). (c) Time-dependent increase of membrane TNF-RII expression by T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 20 mmol/L NAC. Results are expressed in MFI values (mean ± SD, n = 6). *Means P < .01.

NAC increases in a dose- and time-dependent manner membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression on human T cells. (a) Time-dependent increase of membrane TNFα expression on T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 20 mmol/L NAC. Results are expressed in MFI values (mean ± SD, n = 6). *Means P < .01. (b) NAC induces a dose-dependent increase of membrane TNFα (○), TNF-RI (▪), and TNF-RII (□) expression on T cells stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin. Results are expressed in percent of increase (mean ± SD, n = 6). (c) Time-dependent increase of membrane TNF-RII expression by T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the absence (dashed line) or presence (solid line) of 20 mmol/L NAC. Results are expressed in MFI values (mean ± SD, n = 6). *Means P < .01.

Thus, NAC induces an early and sustained increase of membrane TNFα expression and also increases TNF-RII expression on human stimulated PB T cells.

NAC modulates TNFα and TNF-RII expression by acting both at pretranscriptional and posttranscriptional levels.Similar to the membrane expression, the production of soluble TNFα by T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin, detectable at 2 hours (145 ± 35 pg/mL, mean ± SD, n = 6), increased in a time-dependent manner (12.7 ± 1.1 ng/mL at 16 hours). Until 6 hours after stimulation, NAC-increased membrane TNFα expression was associated with an inhibition of soluble TNFα release (Fig 3a) whereas TNFα mRNA expression was unaffected (Fig 3c). After 8 hours, NAC increased membrane and soluble TNFα as well as TNFα mRNA expression (Fig 3a and c). In a similar manner, the early increase of membrane TNF-RII expression induced by NAC was associated with a decrease of sTNF-RII release (Fig 3b) without effect on mRNA expression (Fig 3c). After 24 hours of stimulation, the expression of membrane and soluble TNF-RII and corresponding mRNA were increased (Fig 3b and c).

Effect of NAC on the mRNA and soluble versus membrane form expression of TNFα and TNF-RII. (a) Kinetics expression of membrane and soluble TNFα by T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence of 20 mmol/L NAC. Membrane TNFα (□) is expressed in percent of increase of MFI values and TNFα production (▪) in percent of increase or decrease of TNFα release (mean ± SD, n = 6). (b) Soluble TNF-RII was determined on T cells stimulated for 48 hours with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence (solid line) or the absence (dashed line) of 20 mmol/L NAC. Results are expressed in pg/mL (mean ± SD, n = 6). (c) Kinetics analysis of TNFα and TNF-RII mRNA expression by stimulated T cells in the presence of 20 mmol/L NAC. T cells were stimulated for the indicated time and TNFα, TNF-RII, and β-actin mRNA expression was determined by PCR.

Effect of NAC on the mRNA and soluble versus membrane form expression of TNFα and TNF-RII. (a) Kinetics expression of membrane and soluble TNFα by T cells stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence of 20 mmol/L NAC. Membrane TNFα (□) is expressed in percent of increase of MFI values and TNFα production (▪) in percent of increase or decrease of TNFα release (mean ± SD, n = 6). (b) Soluble TNF-RII was determined on T cells stimulated for 48 hours with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence (solid line) or the absence (dashed line) of 20 mmol/L NAC. Results are expressed in pg/mL (mean ± SD, n = 6). (c) Kinetics analysis of TNFα and TNF-RII mRNA expression by stimulated T cells in the presence of 20 mmol/L NAC. T cells were stimulated for the indicated time and TNFα, TNF-RII, and β-actin mRNA expression was determined by PCR.

Thus, the increase of membrane TNFα and TNF-RII expression induced by NAC on stimulated T cells may be associated with an inhibition of their shedding. Such effect is added to a later increase of the corresponding mRNA expression.

Free thiol-containing molecules increase membrane TNFα and TNF-RII.We have evaluated whether the effect of NAC on membrane TNFα and TNF-RII expression was related to the thiol group or to the antioxidant activity. All the compounds tested presenting a free thiol group increased both membrane TNFα and TNF-RII expression on stimulated T cells with equal potencies (Table 1). In contrast, antioxidants without a thiol group or molecules with a thiol group blocked (GS-SG or SMC) were ineffective. Because compounds with a free thiol group are potentially able to increase the intracellular GSH levels,10 we have evaluated whether the increase of TNFα and TNF-RII expression may result from GSH neosynthesis. As expected,23 BSO prevented the increase of intracellular GSH level induced by NAC in stimulated T cells (data not shown), but did not prevent the increase of membrane TNFα and TNF-RII expression induced by NAC (Table 1). Thus, compounds with a free thiol group increase membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression on stimulated T cells through a mechanism independent of de novo GSH synthesis.

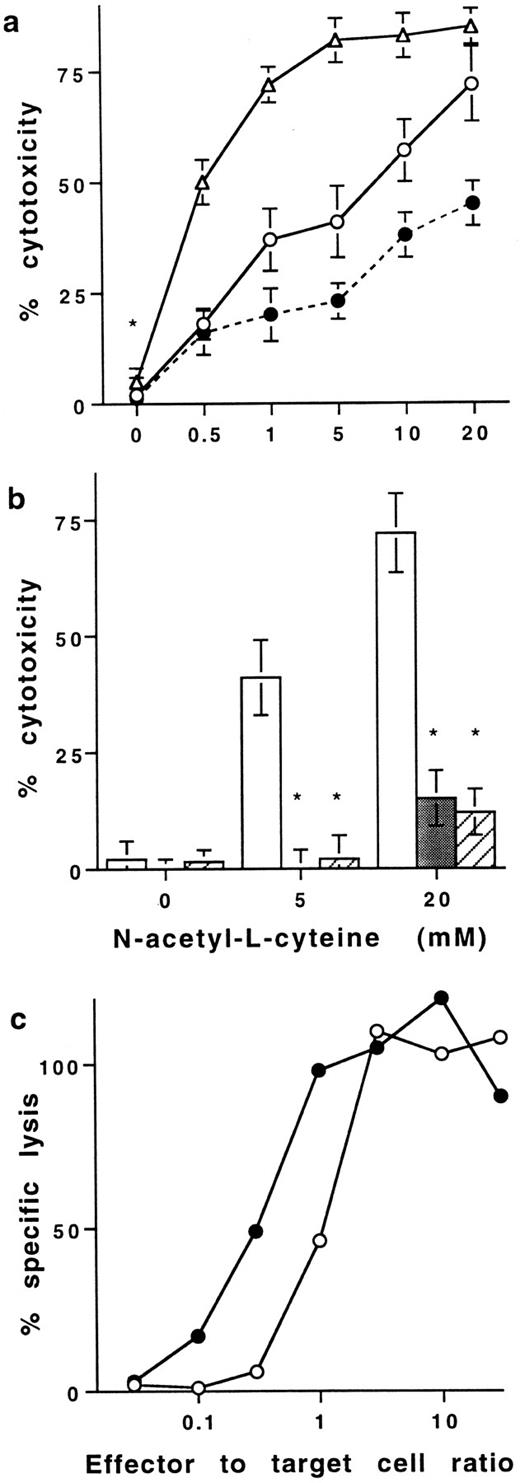

Effect of NAC on T-cell–dependent cytotoxicity.The increase of membrane TNFα induced by NAC on human T cells was found to be of functional significance. Neither resting (data not shown) nor PMA plus ionomycin stimulated PB T cells were cytotoxic for HL60 cells (Fig 4a). Indeed, optical density values were similar (0.65 ± 0.05, 0.68 ± 0.09, and 0.62 ± 0.09; mean ± SD, n = 6) when HL60 cells at a resting state were cultured alone, with PFA-fixed resting T cells, or with T cells treated with PMA plus ionomycin before fixation with PFA, respectively. However, stimulated T cells treated with 20 mmol/L NAC killed 75 ± 9% of HL60 at an effector to target cell ratio of 1:1 (Fig 4a). The concentration of NAC required to kill 50% of HL60 was 6 and 0.6 mmol/L with effector-to-target cell ratios of 1:1 and 10:1, respectively. Two different neutralizing anti-TNFα Ab significantly prevented the killing of HL60 (98 ± 5 and 75 ± 9 inhibition, mean% ± SD, n = 8, P < .05; Fig 4b). Similar results were obtained with K562 (data not shown). Because NAC is known to protect cells against death, we have also evaluated whether NAC modulated target cell sensitivity to TNFα-mediated cell death. When cytotoxic assays were performed in the presence of 20 mmol/L NAC, HL60 cells were partly protected against death induced by NAC-treated T cells. Indeed, with an effector to target cell ratio of 1:1, T cells treated with 20 mmol/L NAC killed 75 ± 9% and 42 ± 5% of HL60 cells when NAC was absent or present during the assay, respectively (Fig 4a). Thus, NAC confers to human PB T cells the ability to kill tumoral cell lines in a membrane TNFα-dependent pathway.

Effect of NAC on T cell–mediated cytotoxicity. (a) Cytotoxic activity of purified human PB T cells stimulated in the presence of NAC against HL60 cells in a resting state. In all the experiments, T cells were stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence of increasing concentrations of NAC and then washed before fixation with PFA. Cytotoxic assays were performed against HL60 cells at the effector to target cells ratio 1:1 (○) and 10:1 (▵). In some experiments performed with an effector to target cell ratio of 1:1, 20 mmol/L NAC were added in the medium during the cytotoxic assays (•). Results are expressed in percent of cytotoxicity (mean ± SD, n = 8). (b) Neutralization of the T cell–dependent cytotoxicity with anti-TNFα Abs. The cytotoxic assays were performed at the effector to target cell ratio of 1:1 with T cells stimulated without or with NAC in the absence (□) or the presence of two different neutralizing anti-TNFα Abs (▨ and ▪). Results are expressed in percent of inhibition of cytotoxicity (mean ± SD, n = 8). *Means P < .01. (c) Effect of NAC on lytic activity of antigen-specific mouse CTL. The effector CTL QB7.3.2 clone was pretreated (•) or not (○) with 20 mmol/L NAC during 3 to 12 hours and then washed but not fixed with PFA. 51Cr-labeled P815 target cells, pulsed with the peptide PbCS 252-260, were incubated with the pretreated CTL at the indicated effector to target cells ratio. Cytotoxic assays were performed in the absence of exogenous NAC. Results are from one out of three representative experiments.

Effect of NAC on T cell–mediated cytotoxicity. (a) Cytotoxic activity of purified human PB T cells stimulated in the presence of NAC against HL60 cells in a resting state. In all the experiments, T cells were stimulated for 16 hours with PMA plus ionomycin in the presence of increasing concentrations of NAC and then washed before fixation with PFA. Cytotoxic assays were performed against HL60 cells at the effector to target cells ratio 1:1 (○) and 10:1 (▵). In some experiments performed with an effector to target cell ratio of 1:1, 20 mmol/L NAC were added in the medium during the cytotoxic assays (•). Results are expressed in percent of cytotoxicity (mean ± SD, n = 8). (b) Neutralization of the T cell–dependent cytotoxicity with anti-TNFα Abs. The cytotoxic assays were performed at the effector to target cell ratio of 1:1 with T cells stimulated without or with NAC in the absence (□) or the presence of two different neutralizing anti-TNFα Abs (▨ and ▪). Results are expressed in percent of inhibition of cytotoxicity (mean ± SD, n = 8). *Means P < .01. (c) Effect of NAC on lytic activity of antigen-specific mouse CTL. The effector CTL QB7.3.2 clone was pretreated (•) or not (○) with 20 mmol/L NAC during 3 to 12 hours and then washed but not fixed with PFA. 51Cr-labeled P815 target cells, pulsed with the peptide PbCS 252-260, were incubated with the pretreated CTL at the indicated effector to target cells ratio. Cytotoxic assays were performed in the absence of exogenous NAC. Results are from one out of three representative experiments.

Similar results were obtained using peptide PbCS 252-260 specific murine CTL clones pretreated with NAC. Results showed that a pretreatment of the CTL clones with 20 mmol/L NAC for 3 or 12 hours before addition to target cells increased their cytotoxic activity. Indeed, the effector to target cell ratios required to kill 50% of the target cells were 1 and 0.15 with CTL clones not treated or treated for 3 hours with NAC, respectively (P < .05). These ratios were 0.8 and 0.1 with CTL clones not treated or treated for 12 hours with NAC, respectively (Fig 4c) (P < .01).

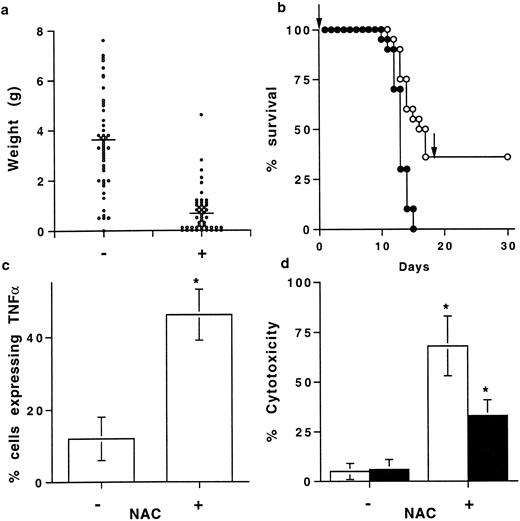

NAC prevents in vivo tumor growth.Based on our in vitro results regarding TNFα and TNF-R processing, the in vivo antitumoral activity of NAC was evaluated in B6D2F1 mice injected with L1210 cells. At day 11 the weight of the intraperitoneal tumors was lower in NAC-treated than in nontreated mice (0.8 ± 0.2 g and 3.1 ± 0.8 g, respectively; mean ± SEM, n = 50, P < .05) (Fig 5a). Surprisingly, 36% of NAC-treated mice did not develop tumors whereas all of the nontreated mice did (Fig 5a). Kinetic experiments showed that NAC only slightly delayed tumor growth (data not shown) and survival (Fig 5b). After day 9, the percentage of TNFα-expressing cells in the tumors and in the spleens was significantly higher in NAC-treated mice developing a tumor than in nontreated mice, while MFI values were not significantly different (data not shown). Indeed, at day 11, 46 ± 7 compared with 12 ± 6 (mean% ± SD, n = 5, P < .05) of cells from the tumors (Fig 5c) and 38 ± 8 compared with 8 ± 5 spleen cells (mean% ± SD, n = 5, P < .05; data not shown) expressed membrane TNFα in NAC-treated and nontreated mice, respectively. In parallel, the frequencies of CD3-positive cells in tumors were 42 ± 12 and 20 ± 10 in NAC-treated and nontreated mice, respectively (mean% ± SEM, n = 5). At day 11, spleen cells from NAC-treated mice without tumor were more efficient than spleen cells from NAC-treated mice with a tumor in killing L1210 cells (68 ± 22 and 36 ± 9 cytotoxicity, respectively, mean% ± SD, n = 8, P < .05), whereas spleen cells from nontreated mice were ineffective (Fig 5d). Moreover, NAC was not toxic in vitro for L1210 cells as assessed by trypan blue coloration and 3H-thymidine uptake (data not shown). L1210 cell death was partially prevented by a neutralizing anti-mouse TNFα Ab (65 ± 8% inhibition; Fig 5d). In addition, NAC prevented tumor appearance in 18 out of 50 mice. These mice, reinjected at day 18 with L1210 cells and not further treated with NAC, were still alive 1 month later (Fig 5b).

NAC prevents in vivo tumoral development. (a) Tumor weight in mice treated orally with 5 g/L NAC. B6D2F1 mice were injected with L1210 cells, treated (+) or not (−) with NAC, and the tumor weight, determined at day 11, was expressed in g (mean ± SEM, n = 50). Bars represent the mean weight. (b) Survival of mice injected with L1210 and treated (•) (n = 50) or not (○) (n = 50) with NAC. Results are expressed in percent of animal survival. Arrows represent the time of L1210 cell injection. (c) Effect of NAC on membrane TNFα expression by cells from the tumors. Membrane TNFα was determined by FACS on cells from the tumors from mice treated (+) or not (−) with NAC. Results are expressed as a percentage of cells expressing membrane TNFα (mean ± SD, n = 5). *Means P < .05. (d) Cytotoxic activity of PFA-fixed spleen cells from NAC-treated mice (+) and not treated mice (−) was determined against L1210, in the presence (▪) or not (□) of a neutralizing anti-TNFα Ab. Results are expressed in percent of cytotoxicity (mean ± SD, n = 8). *Means P < .05.

NAC prevents in vivo tumoral development. (a) Tumor weight in mice treated orally with 5 g/L NAC. B6D2F1 mice were injected with L1210 cells, treated (+) or not (−) with NAC, and the tumor weight, determined at day 11, was expressed in g (mean ± SEM, n = 50). Bars represent the mean weight. (b) Survival of mice injected with L1210 and treated (•) (n = 50) or not (○) (n = 50) with NAC. Results are expressed in percent of animal survival. Arrows represent the time of L1210 cell injection. (c) Effect of NAC on membrane TNFα expression by cells from the tumors. Membrane TNFα was determined by FACS on cells from the tumors from mice treated (+) or not (−) with NAC. Results are expressed as a percentage of cells expressing membrane TNFα (mean ± SD, n = 5). *Means P < .05. (d) Cytotoxic activity of PFA-fixed spleen cells from NAC-treated mice (+) and not treated mice (−) was determined against L1210, in the presence (▪) or not (□) of a neutralizing anti-TNFα Ab. Results are expressed in percent of cytotoxicity (mean ± SD, n = 8). *Means P < .05.

DISCUSSION

Early after stimulation, thiols increase membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression on T cells and inhibit the release of the soluble forms without affecting the mRNA expression. Because the soluble proteins result from the shedding of the membrane forms mediated by divalent cation-dependent protease(s),22 thiols may inhibit the activity of these enzymes. Thiols can modulate the activity of numerous enzymes through different mechanisms such as oxido-reduction of thiol groups or chelation of cations required for enzymatic activity.15,28 This last property could be involved because the effect of thiols on TNFα and TNF-R expression was partly inhibited by adding Zn++ (data not shown). Moreover, in agreement with studies showing that the activation of the TNF converting enzyme required a stimulation with PMA,13,15,22 29 thiols were only effective on PMA-stimulated T cells. T cells do not import extracellular GSH but import the precursor L-cysteine, which is rapidly oxidized in L-cytidine, nonavailable for T cells. In contrast, NAC is easily taken up by the cells and deacetylated intracellularly to allow its incorporation in neosynthetized GSH. Although these thiol-containing molecules differ in their ability to enter into the cells, they all increase membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression on stimulated T cells. These activities of thiols were not mediated through a neosynthesis of GSH, suggesting that they do not need to enter into the cells to modulate TNFα and TNF-R expression. Taken together, these data suggest that thiols may modify the activity of a molecule(s) located at the cell surface.

In addition to inhibiting shedding, which occurs as long as TNFα, TNF-R, and the converting enzymes are expressed, thiols increased the levels of TNFα and TNF-R mRNA later on. This effect could account for the late increase in expression of both membrane and soluble forms induced by NAC. NAC-increased membrane TNFα requires a stimulation including PMA (PMA plus ionomycin or anti-CD3 MoAb), which activates the transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1. However, previous studies have reported that (1) the NF-κB sites located in the human TNFα promoter are not required for transcriptional induction in response to PMA30 and (2) AP-1 elements transduce signals responsible for the transcription of TNFα mRNA in response to a stimulation with PMA.31 Because antioxidants inhibit both DNA-binding and transactivating activities of NF-κB but increase AP-1 activity,32-35 we can hypothetize that the NAC-induced increase of TNFα and TNF-R mRNA expression may result from an increase of AP-1 activity. However, we cannot exclude that in association with other stimuli, NAC may act at both pre- and posttranscriptional levels to regulate TNFα and TNF-R expression and that NAC may prevent TNFα mRNA degradation because this is unstable.36 Thus, the ability of NAC to act at the pretranscriptional and posttranscriptional levels may explain its early and sustained effect on membrane TNFα expression.

Although increasing both TNFα and TNF-R expression, NAC was not cytotoxic for T cells at the concentrations used, as assessed by trypan blue and propidium iodide labeling37 (some data not shown). In contrast, NAC increased IL-2 production, CD25 expression, and proliferation of stimulated T cells.6,7 The ability of NAC to favor TNF/TNF-R and IL-2/CD25 interactions may explain, at least in part, the T cell costimulatory activity of NAC. Indeed, membrane TNFα acts on TNF-R-bearing T cells by increasing IL-2 production, CD25 expression, and proliferation.38 Conversely, IL-2 increases TNF-R expression.21 Thus, the increase of membrane CD25, TNFα and TNF-R expression, and IL-2 production induced by NAC may contribute to its costimulatory activity on human T cells.

NAC confers cytotoxic properties to human PB T cells. NAC induced a rapid increase of membrane TNFα expression followed by a later increase of soluble TNFα production, suggesting that NAC potentiates both these TNFα-dependent cytotoxic pathways. Although the implication of a TNFα-dependent pathway in this activity remains undefined, NAC potentiated the cytotoxic activity of mouse CTL clones through a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-dependent pathway. Experiments are in progress to define the mechanism by which NAC increases the cytolytic activity of these clones. Concerning human T cells, NAC could affect the expression of other molecules involved in cell death. The fixation of T cells allows us to exclude the potential involvement of soluble mediators (such as TNFα) and of the perforin pathway.39 Moreover, TNFβ was not expressed on stimulated T cells at the time point used40 (some data not shown). Although Fas-ligand (Fas-L) is implicated in the death of T cells in the periphery,41 the effect of NAC on its expression has not been evaluated. Nevertheless, the involvement of Fas-L mediated cell death in the cytotoxic assays performed in the presence of NAC is unlikely because NAC inhibits Fas expression42 and protects cells against Fas-mediated apoptosis.42,43 Previous studies have reported that GSH and NAC increased the LAK and NK cells in vitro through a mechanism dependent on IL-2 production and on GSH neosynthesis.8-10 We have observed that NAC also increased membrane TNFα expression on stimulated LAK cells (data not shown). However, the effect of thiols on TNFα and TNF-R processing reported here was independent of GSH neosynthesis. Taken together, these data underline that thiols may act through different pathways to potentiate the cytotoxic activity of T cells.

Membrane TNFα is involved in killing by cell-cell contact after interaction with membrane TNF-R expressed on the target cells.44 A recent study has shown that membrane TNFα binds mainly to TNF-RII.45 HL60 cells in a resting state, used as target cells in our in vitro cytotoxic assays, expressed only TNF-RII, as assessed by FACS analysis (MFI-background of 1 ± 1 and 12 ± 3, mean ± SD, n = 6, for TNF-RI and TNF-RII, respectively) and as previously reported.46 This observation shows that the TNFα-dependent cytotoxicity induced by NAC can be mediated at least through TNF-RII. However, we cannot exclude that NAC-treated T cells may also kill through TNF-RI as we have observed, by FACS analysis, that NAC increases the expression of both TNF-RI and TNF-RII on HL60 cells previously stimulated for 24 hours with PMA (110 ± 25 and 179 ± 39 increase at 20 mmol/L, respectively, mean% ± SD, n = 6). Nevertheless, the main point is that, because of its ability to increase both membrane TNFα and TNF-R expression, NAC potentiates the T cell–dependent antitumoral responses. NAC may also have opposite effects on the TNFα-sensitivity of tumoral cells depending on their state of activation. In one hand, NAC increases TNF-R expression on activated tumoral cell lines and thus may increase their sensitivity to membrane TNFα-dependent cell death. In another hand, because of its antioxidant properties47-49 and ability to increase intracellular GSH levels,50,51 NAC partly protects target cells against the membrane TNFα-mediated cell death.52,53 Overall, NAC appears to increase the ability of nonprofessional (ie, PB T cells) and professional cytotoxic cells to kill target cells. On the basis of the in vitro results using mouse CTL clones, we have evaluated the ability of NAC to prevent in vivo tumor development. In vitro experiments showed that the ability of NAC to increase membrane TNFα expression was only evidenced on stimulated T cells. Consequently, the potential in vivo antitumoral activity of NAC was analysed in a semiallogenic model (B6D2F1 mice injected with L1210 cells), which allows the initiation of a T cell–dependent immune response. Interestingly, one third of NAC-treated mice did not develop tumors and were resistant to a second inoculation of L1210 cells in the absence of further treatment with NAC. The fact that NAC exerts its costimulatory effect only on stimulated but not on resting T cells suggests that NAC potentiates the development/efficacy of an already initiated immune response. Additional experiments are required to define the mechanisms responsible for this effect. However, this in vivo observation, added to ex vivo experiments, suggests that NAC may increase the frequency of effector cytotoxic T cells able to kill tumoral cells at least in a membrane TNFα-dependent manner. Moreover, a recent study reported that NAC also prevented invasis and metastasis through the inhibition of the gelatinase activity,5 suggesting a beneficial role of NAC at different steps of tumoral development. These data may be related to the ability of thiols to synergize with metabolic drugs (ie, cisplatin) in preventing the development of human ovarian cancer.54

In conclusion, in addition to its T-cell costimulatory activity, NAC enhances the antitumoral activity of T cells in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that NAC has potential for antitumoral therapy to treat TNFα-sensitive tumoral cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to Drs J.P. Aubry and J.F. Gauchat for helpful discussion and Drs J. Knowles and K. Hardy for support and critical review of this manuscript.

Y.D. and P.J. are equivalent contributors.

Address reprint requests to Jean-Yves Bonnefoy, Geneva Biomedical Research Institute, Glaxo Wellcome Research and Development SA, Immunology Department, 14, chemin des Aulx, 1228 Plan-les-Ouates, Geneva, Switzerland.