Abstract

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) DNA has been detected in several human lymphoproliferative disorders. We report a case of HHV-6–infected Burkitt's lymphoma, from which a cell line, designated Katata, has been established. Katata cells had an immature B-cell phenotype with an L3 morphology and carried a t(8; 14)(q24; q32) chromosomal abnormality. The HHV-6 DNA sequences were detected in both the patient's tumor cells and Katata cell line by polymerase chain reaction using three sets of primers that target different regions of HHV-6 DNA. The presence of HHV-6 DNA in Katata cells was also shown by Southern blot hybridization with the BamHI fragment of HHV-6. It is likely that the virus is in a latent state, since (1) virion-associated protein was not expressed in Katata cells, (2) transcriptional level of the immediate-early gene was very low, and (3) no viral particles were observed by electron microscopy. Katata cells were highly tumorigenic in nude mice and the tumor cells also contained HHV-6 DNA. We have successfully obtained several clonal lines by allowing the cells to form colonies in soft agarose and by the limiting dilution method. HHV-6 DNA was detectable in all 13 clones analyzed, suggesting that virtually all Katata cells are infected with HHV-6. This is the first report of a case of HHV-6+ Burkitt's lymphoma in the absence of Epstein-Barr virus. Furthermore, there has been no report of lymphoma cell lines that are persistently and nonproductively infected with HHV-6. The Katata Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, therefore, would provide a useful tool for studies of the mechanisms of HHV-6 latency and reactivation.

HUMAN HERPESVIRUS 6 (HHV-6) was first isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes of patients with various lymphoproliferative disorders,1 and subsequently identified as the principal causative agent of exanthem subitum and acute febrile illness of early childhood.2,3 The primary HHV-6 infection in seronegative adults has been related to various clinical manifestations, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, necrotizing lymphadenitis, mononucleosis-like syndromes, and hepatitis.4-7 Like most other herpesviruses, HHV-6 is likely to remain latent in the host after primary infection and can be reactivated in immunosuppressed states (eg, patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and transplant recipients), leading to critical clinical outcomes such as interstitial pneumonitis and encephalitis.8-14 At present little is known about the mechanisms of latency and reactivation of HHV-6. Therefore, establishment of an in vitro model system is desirable for elucidation of these important issues.

Burkitt's lymphoma is a high-grade B-cell malignancy closely associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The EBV genome is detectable in more than 90% of endemic Burkitt's lymphoma cases from central Africa, whereas a much smaller proportion of sporadic Burkitt's lymphoma cases carry EBV.15 The presence of HHV-6 DNA sequences was shown in several human lymphoid neoplasias such as T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin's disease, and various types of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.16-20 We report here a case of HHV-6+ but EBV− Burkitt's lymphoma in a Japanese woman. We have successfully established an HHV-6–infected cell line from this patient and the data presented here suggest that HHV-6 persists in the cell line in a latent state. This novel cell line would be a useful tool for investigating the mechanisms of viral latency and reactivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

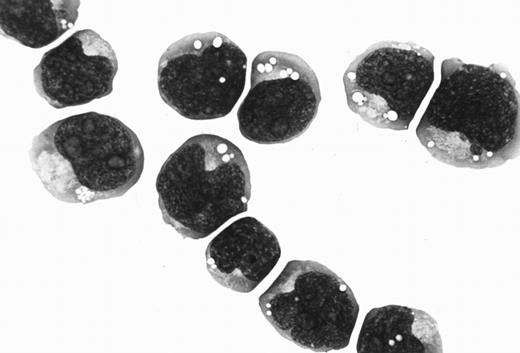

Case history and establishment of cell line.The Katata line was established from a 58-year-old Japanese woman who was referred to our hospital for a growing mass in the epigastric region. On physical examination, a firm nodule, 2 cm in diameter, was also found in her right breast. A diagnosis of Burkitt's lymphoma was made on a biopsy specimen of the breast tumor (Fig 1). Karyotype analysis of the tumor sample disclosed several chromosomal abnormalities including t(8; 14)(q24; q32). Gastric endoscopy revealed tumorous involvement of the stomach. A bone marrow (BM) aspirate showed infiltration of lymphoma cells with an L3 morphology (French-American-British classification) that amounted to 42.3% of the nucleated cells. The patient was treated with two courses of combination chemotherapy of cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone, but the chemotherapeutic response was minimal. The disease progressed into a leukemic phase and she died of septicemia 6 weeks after admission. Serological titers for EBV were as follows: antiviral capsid antigen (VCA) IgG, 1:40; anti-VCA IgM, <1:10; anti-VCA IgA, <1:10; antiearly antigen IgG, <1:10; and antinuclear antigen, <1:10. The anti-HHV-6 antibody was not tested.

(A) Histology of the original biopsy specimen from the breast tumor, showing Burkitt's lymphoma with starry-sky appearance. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification [OM] × 400). (B) Imprint smear of the tumor, showing lymphoma cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, generally round nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (OM × 1,000).

(A) Histology of the original biopsy specimen from the breast tumor, showing Burkitt's lymphoma with starry-sky appearance. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification [OM] × 400). (B) Imprint smear of the tumor, showing lymphoma cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, generally round nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (OM × 1,000).

A heparinized BM sample was obtained 10 days before her death, when her BM aspirate contained 78.0% lymphoma cells. Mononuclear cells were separated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation and suspended at 5 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (FCS) and antibiotics (100 IU/mL of penicillin and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin). The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air and fed every other day by partial medium change.

Immunophenotyping and chromosome analysis.Expression of cell surface antigens was studied by the indirect immunofluorescence method using the following monoclonal antibodies: OKT6 (CD1) (Ortho, Raritan, NJ), Leu5b (CD2), Leu4 (CD3), Leu3a (CD4), Leu1 (CD5), OKT16 (CD7), Leu2a (CD8) (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) for T-cell antigens; Leu12 (CD19) (Becton Dickinson), B1 (CD20) (Coulter, Hialeah, FL) for B-cell antigens; J5 (CD10) (Coulter) for common ALL antigen; My7 (CD13), Mo2 (CD14), My9 (CD33) (Coulter) for myelomonocytic antigens; and OKIa1 (HLA-DR) (Ortho) for Ia antigen. Surface Ig expression was analyzed by the direct immunofluorescence method using fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rabbit anti-human Ig (γ, α, μ, δ, κ, λ) (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark). Expression of cytoplasmic Ig was evaluated on acetone-fixed cytospin smears with the FITC-conjugated anti-human Ig. Metaphase chromosomes were prepared and banded by trypsin-Giemsa according to the method of Seabright.21

Primers.For HHV-6 DNA amplification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), three sets of primers from different regions of the HHV-6 genome were used. The sequences of the first set of primers (designated primer pair 1) were 5′-CCCATTTACGATTTCCTGCAC-3′ as sense primer and 5′-TTCAGGGACCGTTATGTCATT-3′ as antisense primer, generating a 186-base pair (bp) fragment.19 The second set of primers was derived from a highly conserved region shown to encode the major capsid protein. In this experiment, a two-step amplification procedure was performed to increase the specificity, as previously described.22 The set consisted of outer primers (primer pair 2), 5′-GCGTTTTCAGTGTGTAGTTCGGCAG-3′ and 5′-TGGCCGCATTCGTACAGATACGGAGG-3′, giving a 520-bp fragment, and an inner pair (primer pair 2′), 5′-GCTAGAACGTATTTGCTGCAGAACG-3′ and 5′-ATCCGAAACAACTGTCTGACTGGCA-3′, yielding a 258-bp fragment.22 The third set of primers (primer pair 3), derived from a sequence corresponding to the immediate-early gene, was employed for the determination of HHV-6 variants. The sequences of the primers for this purpose were 5′-TTCTCCAGATGTGCCAGGGAAATCC-3′ and 5′-CATCATTGTTATCGCTTTCACTCTC-3′, resulting in generation of 325-bp and 553-bp fragments for type A and type B variant, respectively.23 For EBV PCR, primers (TC60 and TC61) were used for detection of the BamW region of the EBV genome.24

PCR analysis.DNA was obtained using the phenol chloroform-extraction technique after proteinase K digestion. A total of 100 ng of genomic DNA was amplified in 50 μL of PCR buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 50 mmol/L KCl, 1.6 mmol/L MgCl2) with 0.2 mmol/L of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 U Taq polymerase enzyme (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), and 0.2 μmol/L of each pair of primers. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 94°C for 3 minutes for denaturation followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 57°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute. A terminal extension of 72°C for 5 minutes was performed after completion of the 30 cycles. A total of 20% of the amplification products (10 μL) was electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel followed by ethidium bromide staining and visualization under UV light for the presence of DNA bands of appropriate sizes.

For reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, total RNA was extracted by the acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method.25 First strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of DNase I-treated RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (M-MLV RT). Briefly, the extracted RNA was incubated in 20 μL of buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 75 mmol/L KCl, 3.0 mmol/L MgCl2 , 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.5 mmol/L deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 100 ng of 6-mer random primer, 70 U of RNase inhibitor, and 200 U of M-MLV RT (GIBCO-BRL) for 60 minutes at 37°C and then for 10 minutes at 70°C to stop the reaction. The cDNA was amplified for 30 cycles with the same protocol as described above. β-actin was used as a housekeeping gene to control the quantity of the cDNA and PCR reactions. Primers used for β-actin were 5′-ACCTTCAACACCCCAGCCATG-3′ for sense and 5′-GGCCATCTCTTGCTCGAAGTC-3′ for antisense, generating a 309-bp fragment.26

Southern blot analysis.To detect HHV-6 DNA by Southern blot analysis, we used a probe containing a BamHI fragment (6.9 kb) of HHV-6, which was cloned DNA inserted into a plasmid (pH6Z-101) (supplied by Dr P. E. Pellett, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). This probe proved to be specific for HHV-6. Aliquots of 10 μg of genomic DNA were digested with BamHI restriction enzyme and size-fractionated by electrophoresis in a 0.75% agarose gel. The DNA in the gel was transferred onto a nylon membrane filter. The filter was treated with prehybridization buffer (50% formamide, 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 250 mmol/L sodium phosphate, 250 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA) and hybridized in the same buffer overnight at 42°C with the random-primed, 32P-labeled 6.9-kb fragment of HHV-6. After washing, the filter was exposed to an autoradiographic film at −80°C with an intensifying screen.

Western blot analysis.A mouse monoclonal antibody (C3 108-103) was used to detect a major structural protein of HHV-6 (provided by Dr P.E. Pellett). This antibody recognizes a 101-kD polypeptide as the major immunoreactive virion protein specific for HHV-6B.27,28 Proteins (corresponding to 3 × 105 cells) were subjected to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrophoretically transferred onto a nitrocellulose filter, as previously described.29 The filter was blocked with 5% skim milk and incubated for 1 hour with a 1:500 dilution of the antibody. Second-step reaction was performed by incubation of the washed filter with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse antibody for 1 hour. Reactive proteins were detected by incubation of the washed filter in the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) followed by exposure to an autoradiographic film.

Tumorigenicity assay in nude mice.Four- to five-week-old athymic nude mice were used for the examination of tumorigenicity. Exponentially growing cells (2 to 5 × 107 cells) with a viability greater than 95% were suspended in 1.0-mL serum-free RPMI 1640 medium and inoculated subcutaneously into the backs of mice. The mice were regularly observed for tumor occurrence up to 8 weeks following inoculation. The tumors were excised and subjected to analysis for the presence of HHV-6 DNA as well as histological examination.

Cell cloning.Cell cloning was performed by the method of colony formation in agarose. Exponentially growing Katata cells suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.3% agarose (Sea Plaque; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) and 20% FCS were layered onto an underlayer formed by 0.5% agarose. Two hundred cells were seeded on each 60-mm petri dish. The cultures were incubated under standard culture conditions and observed regularly under an inverted microscope. A colony of more than 20 viable cells was scored as a clone 2 weeks following seeding. The cloning efficiency was determined from the average of three experiments. Cell cloning was also performed by the limiting dilution method. Katata cells were plated into a 96-well plate at 0.5 cell/well containing RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% FCS and fed every 3 days by partial medium change.

RESULTS

Cell line establishment.The cells began to proliferate within a week of initiation of the culture and adapted to growth in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS. This cell line, designated Katata, grows in single-cell suspension with a doubling time of 24 hours. The maximum cell density with stable viability was 3.0 × 106 cells/mL. Cells indicative of cytopathic effects were not seen in the cell line.

Morphology, phenotype, and genotype.The Katata line was predominantly composed of medium-sized cells with round or slightly irregular nuclei and one or more prominent nucleoli. The cytoplasm was basophilic and contained prominent vacuoles (Fig 2). The morphology of Katata cells closely resembled the original lymphoma cells. The results of cell marker analysis of the patient's lymphoma cells and cell line are summarized in Table 1. Both original lymphoma cells and cell line displayed an immunophenotype of immature B cells with a positive reactivity for CD19 and CD20, as well as CD10, but without expression of surface and cytoplasmic Ig. They did not express T-cell and myeloid differentiation antigens. Chromosomal analyses of the cell line were performed on two separate occasions at the earlier passage and over 50th passage. On both occasions, the t(8:14)(q24:q32) translocation was observed in all metaphases analyzed.

Cytospin preparation of Katata cells closely resembling the original lymphoma cells. May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (OM × 1,000).

Cytospin preparation of Katata cells closely resembling the original lymphoma cells. May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (OM × 1,000).

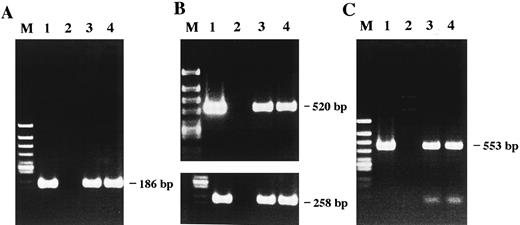

Detection of HHV-6 DNA by PCR and Southern blot analysis.The presence of HHV-6 DNA sequences in the patient's lymphoma cells and Katata cell line was investigated by PCR. Using a set of primer pair 1, DNA samples extracted from both the fresh lymphoma cells and Katata cells were clearly positive for HHV-6 sequences (Fig 3A). The HHV-6 infection was further confirmed by a nested PCR assay targeting the major capsid protein gene of the virus (Fig 3B). With the outer primer pair 2, the first round PCR generated a product corresponding to a 520-bp DNA fragment. One-hundredth of the first round products were then amplified for 10 cycles with the inner primer pair 2′ and a band of expected length (258 bp) was seen in both the patient's lymphoma cells and Katata cells. To identify HHV-6 variant by PCR, we used primer pair 3 covering sites of the immediate-early gene that flanked a region deleted in variant A, such that the resulting fragments were of different sizes.23 Amplification with the primer pair 3 resulted in generation of a 553-bp fragment, indicating that the infecting virus in the patient's tumor cells and derived cell line was HHV-6 variant B (Fig 3C). We used MT-4 cells30 infected with HHV-6B strain Z29 as a positive control.31 The above results were reproducible in at least three independent experiments. To control contamination, the EBV+ Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, Akata,32 known to be negative for HHV-633 was matched with each sample throughout the experiments from DNA extraction to PCR. The search for EBV sequences by PCR in the fresh lymphoma cells and cell line was shown to be negative under the controlled conditions showing a positivity for EBV in Akata cells (data not shown).

Detection of HHV-6 DNA by PCR amplification. The amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. (A) The 186-bp product amplified with primer pair 1 is seen in lanes 1, 3, and 4. (B) A nested PCR assay. A first round of amplification with primer pair 2 generated a 520-bp product seen in lanes 1, 3, and 4. A second round of amplification that was performed with nested primer pair 2′ and one-hundredth of the products of the first round of amplification generated a 258-bp product. (C) Variant determination of HHV-6 by PCR. Generation of a 553-bp product by PCR with primer pair 3 indicates the presence of HHV-6 variant B. The PCR products detected were all of the predicted sizes based on previous reports. Lane 1, HHV-6B–infected MT-4 cells as a positive control; lane 2, Akata cells as a negative control; lane 3, patient's original lymphoma cells; lane 4, Katata cells; lane M, φX174/HincII-cut DNA size marker.

Detection of HHV-6 DNA by PCR amplification. The amplified products were subjected to electrophoresis and stained with ethidium bromide. (A) The 186-bp product amplified with primer pair 1 is seen in lanes 1, 3, and 4. (B) A nested PCR assay. A first round of amplification with primer pair 2 generated a 520-bp product seen in lanes 1, 3, and 4. A second round of amplification that was performed with nested primer pair 2′ and one-hundredth of the products of the first round of amplification generated a 258-bp product. (C) Variant determination of HHV-6 by PCR. Generation of a 553-bp product by PCR with primer pair 3 indicates the presence of HHV-6 variant B. The PCR products detected were all of the predicted sizes based on previous reports. Lane 1, HHV-6B–infected MT-4 cells as a positive control; lane 2, Akata cells as a negative control; lane 3, patient's original lymphoma cells; lane 4, Katata cells; lane M, φX174/HincII-cut DNA size marker.

The Katata cell line was also examined for the presence of HHV-6 DNA by Southern blot hybridization using the radiolabeled BamHI fragment of HHV-6B (Z29). A single band was detected at 6.9 kb in the DNA sample from Katata cells, but no hybridization was observed in the control lane that contained DNA from Akata cells (Fig 4).

Detection of HHV-6 DNA by Southern blot analysis. Total cellular DNAs were digested with BamHI, subjected to electrophoresis through a 0.75% agarose gel, transferred onto a nylon-membrane filter, and hybridized with the 32P-labeled BamHI fragment of HHV-6 DNA. A hybridizaion band at 6.9 kb is seen in lanes 1 and 3. Positions of size markers are shown on the left. Lane 1, HHV-6–infected MT-4 cells; lane 2, Akata cells; lane 3, Katata cells.

Detection of HHV-6 DNA by Southern blot analysis. Total cellular DNAs were digested with BamHI, subjected to electrophoresis through a 0.75% agarose gel, transferred onto a nylon-membrane filter, and hybridized with the 32P-labeled BamHI fragment of HHV-6 DNA. A hybridizaion band at 6.9 kb is seen in lanes 1 and 3. Positions of size markers are shown on the left. Lane 1, HHV-6–infected MT-4 cells; lane 2, Akata cells; lane 3, Katata cells.

Nonproductive infection of HHV-6 in Katata cells.Having shown that Katata cells were infected with HHV-6, we were next interested in determining whether the cell line is persistently producing the virus or latently infected. For this purpose, we first employed Western blot analysis to detect a virion protein using a monoclonal antibody C3 108-103. This antibody reacts with a 101-kD virion-associated antigen that is not expressed in HHV-6–latently infected cells.27 28 This protein was not detected in Katata cells, while a major band was seen at 101 kD in HHV-6–infected MT-4 cells where viral production was taking place (Fig 5A). We next targeted to detect mRNA that is transcribed in productive HHV-6 infection but not in latent infection. In all known human herpesviruses, the immediate-early gene is the first gene to be transcribed in the productive infection, and expression of this gene precedes viral DNA replication. RT-PCR analysis was performed to determine if mRNA transcribed from the immediate-early gene (IE mRNA) was present in Katata cells. After amplification for 30 cycles, IE mRNA was not or barely detectable in Katata cells, whereas HHV-6–producing MT-4 cells showed an abundant level of IE mRNA (Fig 5B). In contrast, β-actin mRNA was uniformly present in all RNA samples. To confirm that the specific amplification product was obtained from the cDNA and not from contaminating genomic DNA, simultaneous reactions were performed with omission of the RT. Our RNA samples were essentially free of contaminating DNA, because in the absence of RT we could not detect any amplified DNA. The above results were reproducible in RT-PCR analysis using another primer set derived from the IE gene region (data not shown). We also performed an electron microscopic study of Katata cells. There were no viral particles observed either in the cells or in the extracellular spaces.

(A) Western blot analysis for detection of virion-associated antigen of HHV-6. Proteins were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose filter. The proteins were reacted with a monoclonal antibody C3 108-103, followed by incubation with peroxidase-labeled antimouse antibody. The blots were developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method. A 101-kD band is seen in lane 1. Positions of weight markers are indicated on the left. (B) RT-PCR analysis for detection of the immediate-early gene transcript of HHV-6. Isolated RNAs were used for cDNA synthesis and the cDNAs were PCR-amplified with primer pair 3 in the region corresponding to the immediate-early gene. The expected product of 553 bp is seen in lane 1. All cDNAs were subjected in parallel to amplification of the housekeeping gene β-actin, which was expressed at a comparable amount in all samples. Lane 1, HHV-6–infected MT-4 cells; lane 2, Akata cells; lane 3, Katata cells; lane M, φX174/ HincII-cut DNA size marker.

(A) Western blot analysis for detection of virion-associated antigen of HHV-6. Proteins were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose filter. The proteins were reacted with a monoclonal antibody C3 108-103, followed by incubation with peroxidase-labeled antimouse antibody. The blots were developed by the enhanced chemiluminescence method. A 101-kD band is seen in lane 1. Positions of weight markers are indicated on the left. (B) RT-PCR analysis for detection of the immediate-early gene transcript of HHV-6. Isolated RNAs were used for cDNA synthesis and the cDNAs were PCR-amplified with primer pair 3 in the region corresponding to the immediate-early gene. The expected product of 553 bp is seen in lane 1. All cDNAs were subjected in parallel to amplification of the housekeeping gene β-actin, which was expressed at a comparable amount in all samples. Lane 1, HHV-6–infected MT-4 cells; lane 2, Akata cells; lane 3, Katata cells; lane M, φX174/ HincII-cut DNA size marker.

Tumorigenicity in nude mice.To test tumorigenic potential of Katata cells, the cells were injected subcutaneously into athymic nude mice. Katata cells produced tumors in 3 of 4 mice at the site of injection with a latency period of 21 to 28 days. The tumors grew to a size of approximately 2 cm in 35 to 42 days after injection with no sign of regression or necrosis. The tumors were excised for histopathologic examination and for detection of HHV-6 DNA sequences. The tumors were composed of monomorphic lymphoid cells with round or slightly irregular nuclei, multiple nucleoli, and basophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures were numerous and the starry-sky appearance was present. Immunohistological examination showed that the tumor cells possessed a B-cell phenotype. The HHV-6 DNA sequences were detected in the tumor cells by PCR using the three different primer sets (primer pairs 1, 2, and 3) (Fig 6). The tumor cells were serially transplantable in nude mice and tumors formed after the fifth passage retained the HHV-6 DNA.

Detection of HHV-6 DNA in the nude mouse tumor. HHV-6 DNA was detected by PCR with each primer set. Lane 1, primer pair 1; lane 2, primer pair 2; lane 3, primer pair 3; lane M, φX174/HincII-cut DNA size marker.

Detection of HHV-6 DNA in the nude mouse tumor. HHV-6 DNA was detected by PCR with each primer set. Lane 1, primer pair 1; lane 2, primer pair 2; lane 3, primer pair 3; lane M, φX174/HincII-cut DNA size marker.

Cell cloning.To obtain cell clones from the Katata cell line, we examined clonability in soft agarose. The cells successfully formed visible colonies 10 to 14 days after plating. The cloning efficiency was 18.9%. The well-separated colonies were picked up and tested for the presence of HHV-6 DNA by PCR after allowing the cells to grow sufficiently in liquid medium. HHV-6 DNA was detectable in all 10 clones analyzed. Three clonal cell lines were also established by the limiting dilution cultures, each of which was shown to contain HHV-6 DNA.

DISCUSSION

In search of a possible involvement of HHV-6 in hematopoietic malignancies, we have encountered a case of Burkitt's lymphoma infected with HHV-6. The established Katata cell line was also positive for HHV-6 that was consistently detectable not only by PCR using three sets of primers from different regions of the HHV-6 genome but also by Southern blot analysis using a 6.9-kb DNA fragment as probe. Katata cells had the same phenotypic markers as the patient's tumor cells and carried t(8; 14)(q24; q32), a characteristic chromosomal translocation of Burkitt's lymphoma, indicating that the line was derived from the original lymphoma cells.

In a series of previous surveys for detection of HHV-6 DNA in Burkitt's lymphoma, only one case of EBV+ African Burkitt's lymphoma was reported to be positive for HHV-6 DNA.17 To our knowledge, our patient presented here is the first case of EBV-free Burkitt's lymphoma in which HHV-6 DNA was detected. Previous studies have shown a higher prevalence rate of HHV-6 antibody in patients with African Burkitt's lymphoma than that in healthy individuals.34,35 The findings of elevated HHV-6 antibody levels and detection of its DNA sequences in at least some cases of Burkitt's lymphoma raised a possibility that this virus might, directly or indirectly, be an important factor in the pathogenesis of this disease. Razzaque et al36 37 showed a direct oncogenic effect of HHV-6 with evidence that human epidermal keratinocytes and mouse fibroblasts acquired tumorigenicity when transfected with the entire HHV-6 genome or specific DNA sequences. Our results that Katata cells exhibited a tumorigenic phenotype such as growth ability in soft agarose and growth in nude mice with persistence of HHV-6 DNA in the serially transplanted nude mouse tumors appear to suggest an oncogenic potential of HHV-6 in this case. Further studies on additional cases are required before drawing final conclusions concerning the role of HHV-6 in the pathogenesis of some types of Burkitt's lymphoma.

Unlike most other cases of Burkitt's lymphoma that express monoclonal surface Ig (usually IgM), Katata cells possessed an immature B-cell phenotype without expressions of surface and cytoplasmic Ig. Katata cells are phenotypically considered to be at the stage of “pre-pre B cell.”38 It is tempting to speculate that HHV-6 might preferentially infect immature blastic B cells rather than mature B cells. Indeed, normal B cells became more susceptible to HHV-6 infection after blastic transformation by EBV infection.34,39 40

In addition to EBV-infected B-cell lines, HHV-6 also infects cell lines of various origins, including T cells, megakaryocytes, and glioblastoma.34,39-41 However, for each cell line the virus is cytopathic and, therefore, the virus propagation must be maintained by transfer of virus to fresh cells or continuous addition of cells to infected cell cultures. Although such cell lines are useful as virus sources, they are not suitable for investigation of the mechanisms of HHV-6 latency from establishment and maintenance to disruption of the latent state, which are the central issues in the etiopathogenesis of HHV-6+ lymphoproliferative disorders. Therefore, it has been desired to establish in vitro model systems for this purpose. HHV-6 in Katata cells is likely to persist in a latent state, as shown by the absence of 101-kD virion antigen, transcript from the IE gene, and viral particles. A total of 13 clonal cell lines derived from Katata cells also retained the HHV-6 DNA. Thus, to our knowledge, the Katata cell line is the first lymphoma cell line persistently and nonproductively infected with HHV-6. The virus in Katata cells was HHV-6 variant B. It has been shown that the B type isolates are less cytolytic than A type isolates.42 The finding may suggest that HHV-6 variant B has a tendency to latent infection in the host cells. In this respect, our cell line would be a good candidate for studying the latency of HHV-6.

Our interest also points toward attempts to induce productive replication of HHV-6 in Katata cells. Kondo et al43 showed that latent HHV-6 in monocytes/macrophages was reactivated by phorbol ester treatment which is known to be a potent activator of EBV.44-46 Treatment of Katata cells with 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate caused an increase in level of IE mRNA (data not shown). The Katata system could provide a useful tool to gain important information as to the mechanisms of HHV-6 reactivation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank P.E. Pellet for the gifts of monoclonal antibody and DNA probe specific for HHV-6. We are also grateful to T. Sata for the advice on use of the probe.

Supported in part by a grant from the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to M.D.).

Address reprint requests to Masanori Daibata, MD, Department of Medicine, Kochi Medical School, Kochi 783, Japan.

![Fig. 1. (A) Histology of the original biopsy specimen from the breast tumor, showing Burkitt's lymphoma with starry-sky appearance. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (original magnification [OM] × 400). (B) Imprint smear of the tumor, showing lymphoma cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, generally round nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain (OM × 1,000).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/3/10.1182_blood.v90.3.1200/4/m_bl_0019f1.jpeg?Expires=1764979350&Signature=EY4cEaotr3NoMleoXxKb0~leLG-F734RoCIXMF4R3kMh4FQ0g9Mf84AxOl3thxWEg8p~6oGzg84DlO7xcOxI2QzrHBqm5pZxbzyyGsmQuoY89UuQXZd12ZFH8UODYTlL9FbvRGpf7XjqSUJRYMloK3TTC8lm1y77a0PaSg2mE1mmxxxW3L353~nJFsBs6HRjlhVNO4KjGLq5eUA0yDHrMhCMtxiAi4g-KdbfIq3kfTL3zH9v~0YFdxFc98HlQqOWs8P-NnPtK5Eg7SQ8fE~rP3RIGICJnfBhs1rdQu50Eq4rdikUiyyX9cUIxZtKobAzhjewKGCCR8Hy8oqZP1fFrQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)