Abstract

Human cultured mast cells (HCMCs) grown from cord blood mononuclear cells in the presence of stem cell factor (SCF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) expressed tryptase but no or low chymase in their cytoplasm. The addition of IL-4 to these cells strikingly increased chymase expression. Consequently, the activity of chymase was significantly higher in IL-4–treated mast cells than that in IL-4–nontreated mast cells, whereas the activity of tryptase and histamine content were comparable in both cells. Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry also showed that secretary granules containing chymase increased in IL-4–treated mast cells. Interestingly, the IL-4–induced increase of chymase expression in HCMCs was accompanied by morphological maturation of the cells. Cytoplasmic projections were few in IL-4–nontreated HCMCs, and a small number of secretary granules were observed, most of which were empty or partially filled with discrete scrolls with rough particles showing immaturity. In contrast, IL-4–treated HCMCs had extremely abundant cytoplasmic projections and had many secretary granules filled with electron-dense crystal materials. Taken together, immature HCMCs grown only with SCF and IL-6 expressed tryptase with no or a low amount of chymase, and addition of IL-4 promoted cell maturation together with the expression of both tryptase and a high amount of chymase. Our findings will raise a possibility of a linear pathway of human mast cell development from tryptase single positive mast cells into tryptase and chymase double positive mast cells as the cells mature and will suggest that this maturation process is promoted by IL-4.

ON THE BASIS OF protease expression, human mast cells have been classified into two phenotypes.1-4 One phenotype, which is designated MCT (tryptase single positive mast cells), contains tryptase but not chymase, while another phenotype, designated MCTC (tryptase and chymase double positive mast cells), expresses both tryptase and chymase, cathepsin G, and carboxypeptidase A. MCT and MCTC have also been reported to be distinguishable ultrastructurally, mainly by the morphological pattern of contents in their granules.5 6 Discrete scrolls are associated with MCT, and crystal, grating, or lattice substructures are associated with MCTC. However, it has been currently unknown whether MCT can differentiate into MCTC or vice versa.

Protease expression in in vitro human mast cells has been examined by several investigators.7-10 The majority of human mast cells developed from cord blood cells by stem cell factor (SCF) expressed tryptase but not chymase, indicating that SCF is not sufficient for the development of MCTC.7,10 In addition, these mast cells did not reach full maturity based on granule-filling criteria even after 14-week culture.7,11-14 In contrast, more than 90% of human mast cells developed in a coculture of cord blood mononuclear cells with 3T3 fibroblasts were the MCTCphenotype and had ultrastructurally mature features with many crystal granules.8 These reports suggested that SCF was sufficient for neither the development of MCTC phenotype nor full maturation of human mast cells. Moreover, these observations suggested that there might be a relation between human mast cell maturation and protease expression and that there would be a factor(s) upregulating chymase expression along with promotion of human mast cell maturation.

The maturation and phenotype differentiation of mast cells has been extensively studied in mice. Phenotype classification of murine mast cells is based on the pattern of expression of the proteases. In murine mast cells, five types of chymase (mouse mast cell protease [MMCP]-1, -2, -3, -4, and -5) and one mast-cell carboxypeptidase and two types of tryptase (MMCP-6 and -7) have been reported.15-22 The plasticity of the protease expression in murine mast cells has been shown.23-29 Bone-marrow–derived immature mast cells cultured with interleukin-3 (IL-3) express predominantly MMCP-5 and mast-cell carboxypeptidase mRNA. Addition of SCF enhanced the expression of MMCP-4, MMCP-6 mRNA, and heparin proteoglycan in the IL-3–dependent mast cells.23-25 Replacement of IL-3 with IL-10 resulted in the expression of MMCP-1 and -2 mRNAs.26,27 In addition, several studies showed that murine mast cell heterogeneity was the result of the differentiation and maturation of common mast cell-committed progenitor cells regulated by cytokines and/or other tissue-specific factors in the microenvironment.30-32 Accordingly, regulation of human mast cell protease expression and maturation by cytokines would be suggested.

Previously, we have reported that human cultured mast cells (HCMCs) grown from cord blood mononuclear cells in the presence of SCF and IL-6 express few or no high affinity IgE receptors (FcεRI),33which is one of the aspects of immature mast cells.34 We reported that IL-4 induced FcεRI on HCMCs, resulting in high histamine releasing activity on crosslinking of FcεRI in IL-4–primed mast cells.33 In addition, IL-4 has various biological effects on HCMCs, including upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) expression and suppression of c-kit.35-37 All of these results strongly suggested that IL-4 is a maturation and differentiation factor for human mast cells. In this report, we found that most HCMCs grown from cord blood mononuclear cells in the presence of SCF and IL-6 expressed tryptase but low or no chymase in their cytoplasm and that IL-4 strongly increased the chymase expression. Consequently, significantly higher chymase activity was observed in HCMCs cultured with IL-4 than those cultured without IL-4. Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry showed that both tryptase and chymase were detected in the granules of IL-4–treated HCMCs, whereas tryptase but little chymase was detected in their granules in IL-4–nontreated HCMCs. Remarkably, along with the increase of chymase expression, IL-4 promoted morphological maturation of HCMCs. These data suggest that IL-4 promotes the development of MCTC accompanied by morphological maturation as well as functional maturation of the cells. Our finding will lead to the proposal that there is a linear pathway of MCTC via MCT along with maturation of the cells and that this maturation process is strongly promoted by IL-4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HCMCs.

HCMCs were obtained as previously described10 with some modification. Briefly, cord blood mononuclear cells were grown in tissue culture flasks (Becton Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ) in α-MEM (GIBCO-BRL, Life Technologies Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (Hyclone Sterile Systems, Inc, Logan, UT) in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL; Ajinomoto Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) for 10 weeks. Adhesive cells like macrophages were eliminated by transferring nonadhesive cells to fresh culture flasks. Then the 10-week cultured HCMCs were divided into two aliquots. One aliquot was cultured with IL-4 (10 ng/mL; a generous gift from DNAX, Palo Alto, CA) in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL), and the other aliquot was cultured without IL-4 in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL). Both aliquots were cultured in 24-well flat-bottomed plates (Becton Dickinson; 5 × 105 cells/mL/well), and half of the media was changed weekly for fresh media supplemented with cytokines.

Immunocytochemical assays.

HCMCs cultured with or without IL-4 in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for indicated periods were cytocentrifuged onto each glass slide, after the total cell number was counted, and fixed with the fixing solution (Muto Pure Chemicals Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) consisting of formaldehyde (8.75%) and acetone (45%) for 1 minute, and the samples were washed three times with Tris-buffered saline. Then the samples were blocked with rabbit serum for 10 minutes followed by incubation with mouse antihuman tryptase or mouse antihuman chymase monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs; 10 μg/mL; Chemicon International, Inc, Temecula, CA) at room temperature (RT) for 1 hour. After washing three times with Tris-buffered saline, the samples were reacted 1:50 with rabbit antimouse IgG (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) at RT for 1 hour and then washed three times. The samples were further reacted 1:50 with soluble complexes of alkaline phosphatase and mouse monoclonal antialkaline phosphatase (DAKO Co Ltd, Glostrup, Denmark) at RT for 1 hour and washed three times. Finally, they were developed with chromogenic substrate at 37°C for 30 minutes.

Measurement of chymase and tryptase activities

HCMCs (1 × 106) cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL) for 21 days were lysed by sonication in 500 μL of the appropriate reaction solution. The activity of tryptase was measured at 22°C by the cleavage of 1.0 mmol/L tosyl-L-arginine methyl ester (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO) in the reaction buffer containing 0.04 mol/L Tris with 0.01 mol/L CaCl2 at pH 8.1 with continuous spectrophotometrical monitoring of absorbance at 247 nm. The activity of chymase was measured at 22°C by the cleavage of benzoyl-L-tyrosine ethyl ester (0.54 mmol/L; Sigma Chemical Co) in the reaction mixture containing 0.04 mol/L Tris with 0.05 mol/L CaCl2, and 25% (vol/vol) methanol at pH 7.8 with continuous monitoring of absorbance at 256 nm.38 39 One unit of enzyme cleaved 1 μmol of substrate per minute. The enzymatic activity was expressed in units per 1 × 106 mast cells.

Assay for histamine content.

HCMCs (2 × 105 cells in 200 μL) cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL) for 21 days were lysed with Triton X (1%; Sigma Chemical Co). The histamine content in the supernatant was measured by an automated fluorometric histamine analyzer (Auto Analyzer II; BRAN & LUEBBE Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Electron microscopic analysis.

HCMCs grown for 10 weeks in the presence of SCF and IL-6 were divided into two aliquots and cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL), respectively, in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for 28 days. Then the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 30 minutes and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in cacodylated buffer at 4°C for 1 hour. After that, the samples were dehydrated in ethanol and embedded in epoxy resin. Thin sections, 60 to 100 nm, were cut on an ultramicrotome from tissue blocks. These sections were collected on mesh copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and then examined under an electron microscope (JEOL100B; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry.

Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry of tryptase and chymase in HCMCs was performed as previously described.40 HCMCs grown for 10 weeks in the presence of SCF and IL-6 were divided into two aliquots and cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL), respectively, in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for 28 days. Then, the cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 30 minutes. HCMCs fixed with glutaraldehyde were dehydrated without postfixation with osmium and embedded in L R White resin (London Resin Co, London, UK). The ultrathin sections mounted on the nickel grids were immersed in 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma Chemical Co) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 5 minutes. The sections were then reacted with primary antibodies (mouse antihuman tryptase or mouse antihuman chymase; Chemicon International, Inc; 2 μg/mL in PBS) for 2 hours, washed twice with PBS, and immersed further in 0.1% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 30 minutes. The sections were then placed in protein A-gold solution (10 nm in diameter; Sigma Chemical Co), diluted 20-fold with PBS for 1 hour, washed with PBS and distilled water, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrated, and examined under an electron microscope. For an immunocytochemical control, the above procedure was performed using subtype-matched mouse IgG1 instead of mouse antihuman tryptase or antihuman chymase.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed by a paired two-way Student'st-test. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

IL-4 increased the chymase expression in HCMCs.

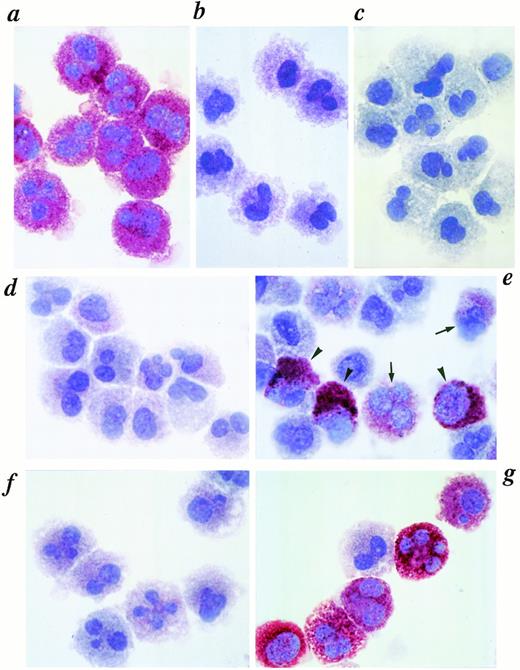

HCMCs were obtained by culturing cord blood mononuclear cells in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks. The cultured cells expressed c-kit (>99%), contained histamine,33 and over half of the cells had polylobed nuclei and the rest had single-lobed nuclei (Fig 1). More than 99% of the cells also expressed high amounts of tryptase determined by immunocytochemical staining using MoAb specific for human tryptase (Fig 1a). In contrast, most of the HCMCs expressed no or an extremely low amount of chymase (MCT or MCTClow) when stained with antihuman chymase MoAb and classified based on Table 1 (Fig 1b). We examined whether IL-4 affected chymase expression in HCMCs. Whereas HCMCs cultured without IL-4 stayed predominantly MCT or MCTClow (Fig 1d and f), addition of IL-4 (10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6 increased HCMCs expressing a high amount of chymase (MCTChigh) (Fig 1e and g). The increase of MCTChigh was observed as early as 5 days after addition of IL-4 (Fig 1e), and a significantly increased number of MCTChigh was observed on day 56 (Fig 1g).

Immunocytochemical staining of tryptase and chymase in HCMCs cultured with or without IL-4. HCMCs grown in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks (defined as day 0 mast cells) were further cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for 56 days. Day 0 mast cells were stained with antitryptase (a), antichymase (b), subclass-matched control mouse IgG1 (c). Day 5 and day 56 mast cells cultured without IL-4 (d and f) or with IL-4 (e and g) stained with antichymase are shown. Typical chymase high positive mast cells (MCTChigh; arrow head) and chymase low positive mast cells (MCTClow; arrow) are indicated (e). This experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Immunocytochemical staining of tryptase and chymase in HCMCs cultured with or without IL-4. HCMCs grown in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks (defined as day 0 mast cells) were further cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for 56 days. Day 0 mast cells were stained with antitryptase (a), antichymase (b), subclass-matched control mouse IgG1 (c). Day 5 and day 56 mast cells cultured without IL-4 (d and f) or with IL-4 (e and g) stained with antichymase are shown. Typical chymase high positive mast cells (MCTChigh; arrow head) and chymase low positive mast cells (MCTClow; arrow) are indicated (e). This experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

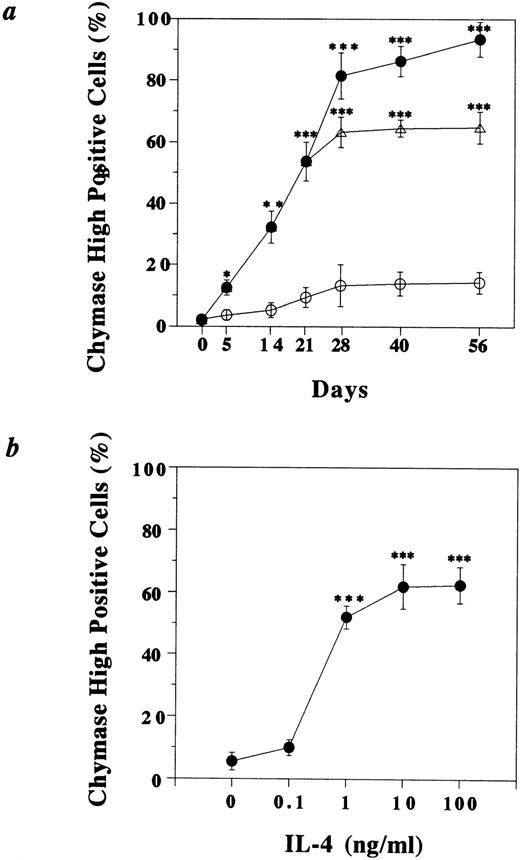

To confirm the effect of IL-4 on the development of MCTChigh, the percentage of MCTChigh was determined at various culture periods after the addition of IL-4 (10 ng/mL; Fig 2a). Before IL-4 was added, only 2.5% ± 0.7% (mean ± SD of three independent experiments) of the cells was MCTChigh (Day 0 in Fig 2a) and 27.2% ± 1.2% was MCTClow, and more than 70% of the mast cells was MCT. Although in the absence of IL-4, the percentage of MCTChigh and MCTClow increased slightly, and on day 56 they reached 14.3% ± 3.5% (Fig 2a) and 45.6% ± 3.6%, respectively. In contrast, addition of IL-4 significantly resulted in the predominance of MCTChigh as shown in Fig 1e and g and Fig 2a. The increase of the percentage of MCTChigh could be observed on day 5 after IL-4 was added to the culture (12.5% ± 3.5%). The percentage of MCTChigh constantly increased and reached 81.5% ± 7.4% on day 28 and 93.5% ± 5.7% on day 56, respectively, and most of the rest of the cells were MCTClow. When IL-4 was withdrawn on day 21, the increase of the percentage of MCTChigh stopped; however, the percentage of MCTChigh stayed 64.8% ± 5.1%, even on day 56 (Fig 2a). The minimum concentration of IL-4 to induce maximum chymase expression in HCMCs was 10 ng/mL (Fig2b). The presence of IL-4 did not affect expression of tryptase, and more than 99% of both IL-4–treated and IL-4–nontreated cells in each observation period expressed tryptase. No significant increase or decrease of the total cell number was observed in either IL-4–treated or IL-4–nontreated HCMCs through the observation period, although a slight increase in the cell number in IL-4–treated cells was observed on day 7 (5.5 ± 0.2 × 105 cells/mL/well), which was the peak cell number through the culture period, and by day 28 the cell number gradually returned to the starting cell number (5.0 × 105 cells/mL/well). No remarkable increase or decrease of the cell number may indicate that the increase of the percentage of MCTChigh in IL-4–added HCMCs is not caused by induction of selective proliferation of the few MCTChigh observed on day 0 or selective death of a large population of MCT. These data suggested that IL-4 strongly promoted the phenotypic change of MCT and MCTClow into MCTChigh.

Time kinetic and dose response analysis of the IL-4–induced development of MCTChigh. HCMCs grown in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks (defined as day 0 mast cells) were further cultured with (closed circle) or without (open circle) IL-4 (10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6. In some experiments, IL-4 was withdrawn (open triangle) after 21-day culture with IL-4. In time kinetic analysis (a) the cells were cytocentrifuged after indicated periods of culture, and chymase was detected immunocytochemically with MoAb specific for human chymase. IL-4–treated mast cells showed statistically significant increased number of MCTChigh compared with IL-4–nontreated mast cells (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). In dose-response analysis (b), 10-week cultured HCMCs were cultured with various concentrations of IL-4 for 21 days and then chymase was detected immunocytochemically (***P < .001). At least 500 cells were counted in each sample under a microscope. The data shown are the mean of three independent experiments.

Time kinetic and dose response analysis of the IL-4–induced development of MCTChigh. HCMCs grown in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks (defined as day 0 mast cells) were further cultured with (closed circle) or without (open circle) IL-4 (10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6. In some experiments, IL-4 was withdrawn (open triangle) after 21-day culture with IL-4. In time kinetic analysis (a) the cells were cytocentrifuged after indicated periods of culture, and chymase was detected immunocytochemically with MoAb specific for human chymase. IL-4–treated mast cells showed statistically significant increased number of MCTChigh compared with IL-4–nontreated mast cells (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001). In dose-response analysis (b), 10-week cultured HCMCs were cultured with various concentrations of IL-4 for 21 days and then chymase was detected immunocytochemically (***P < .001). At least 500 cells were counted in each sample under a microscope. The data shown are the mean of three independent experiments.

IL-4 increased the activity of chymase in HCMCs.

Next, we examined the activity of chymase and tryptase and the histamine content in HCMCs cultured with or without IL-4 (Table 2). The activity of tryptase and the histamine content did not differ between IL-4–treated and IL-4–nontreated cells, whereas the activity of chymase in IL-4–treated mast cells was significantly higher than that in IL-4–nontreated cells. High chymase activity observed in IL-4–treated mast cells is consistent with the data obtained by immunocytochemical assay in which MCTChigh cells predominated when cultured with IL-4.

IL-4 promoted morphological maturation and increased chymase positive granules in HCMCs.

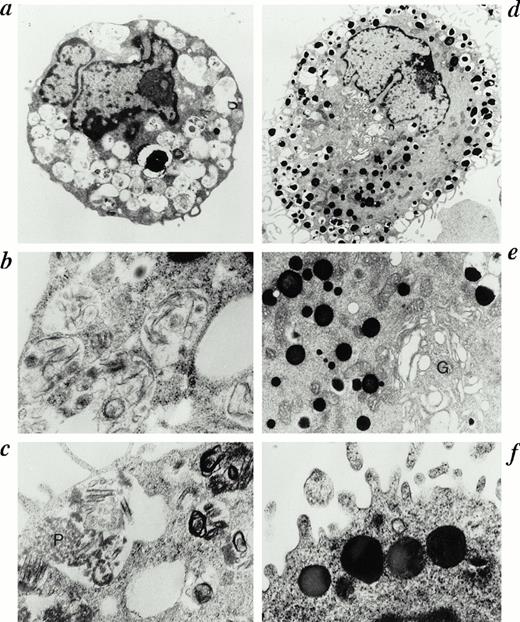

We then performed ultrastructural analysis to examine whether IL-4 induced morphological changes in HCMCs, because MCT and MCTC have been reported to be also distinguishable ultrastructurally, mainly by the pattern of contents in their granules.5,6 In both IL-4–treated and IL-4–nontreated HCMCs, the cells were round or oval shaped, the nuclei were indented or lobulated, and nuclear chromatin was finely condensed at the margin of nuclear membrane (Fig 3a and d). HCMCs cultured without IL-4 had a large and bright nucleolus, suggesting immaturity (Fig 3a). Remarkable morphological differences were noted in cytoplasmic projections and cytoplasmic organelles between HCMCs cultured with IL-4 and those cultured without IL-4. Fewer cytoplasmic projections were observed in HCMCs cultured without IL-4 (Fig 3a). They contained many large empty granules and partially filled granules with discrete scrolls and lamellar structures, and the latter may have been longitudinal sections of discrete scrolls (Fig 3a, b, and c). Granules containing a few rough particles together with discrete scrolls could be observed (Fig 3c). Dense crystal granules were extremely rare in HCMCs cultured without IL-4 (Fig 3a, b, and c). The Golgi apparatus was poorly developed in these mast cells (Fig 3a). The morphology observed in the granules of HCMCs cultured without IL-4 corresponded to the previously reported features of MCT5,6 as well as to those of immature mast cells containing numerous empty or partly full granules which have particles at an early stage, scrolls later, and rarely contain crystals.11-14 In contrast, HCMCs cultured with IL-4 had more abundant cytoplasmic projections, had a remarkably developed Golgi apparatus, and the secretary granules were increased in number (Fig 3d). Most granules in HCMCs cultured with IL-4 were filled with dense, crystal materials as well as compact electron-dense nondiscrete scrolls (Fig 3e and f). Granules containing discrete scrolls were rarely observed in HCMCs cultured with IL-4. Thus, the morphology of the IL-4–treated mast cells corresponded to the ultrastructure of previously reported MCTC5,6 and to the ultrastructure observed in mature mast cells, which have numerous small, dense, crystal granules.11 Therefore, these morphological analyses suggested that IL-4 promotes maturation of human mast cells.

Ultrastructure of human mast cells cultured in the presence or absence of IL-4. HCMCs grown in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks were further cultured with (d, e, and f) or without IL-4 (a, b, and c; 10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for 28 days. HCMCs cultured without IL-4 has few cytoplasmic projections and has an immature nucleus with a large, bright nucleolus (a). Discrete scrolls and lamellar structures with a few rough particles (P in c) are found in the same granules (a and c), and some granules have irregular lamellar structure (b). HCMCs cultured with IL-4 has abundant cytoplasmic projections, well-developed Golgi apparatus (G in d) and numerous granules, which contain dense, crystal materials (d and e), as well as compact electron-dense nondiscrete scrolls (f). Representative results are shown. (Original magnifications: a, ×9,000; b, ×20,000; c, ×20,000; d, ×6,000; e, ×16,000; f, ×22,000.)

Ultrastructure of human mast cells cultured in the presence or absence of IL-4. HCMCs grown in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL) for 10 weeks were further cultured with (d, e, and f) or without IL-4 (a, b, and c; 10 ng/mL) in the presence of SCF and IL-6 for 28 days. HCMCs cultured without IL-4 has few cytoplasmic projections and has an immature nucleus with a large, bright nucleolus (a). Discrete scrolls and lamellar structures with a few rough particles (P in c) are found in the same granules (a and c), and some granules have irregular lamellar structure (b). HCMCs cultured with IL-4 has abundant cytoplasmic projections, well-developed Golgi apparatus (G in d) and numerous granules, which contain dense, crystal materials (d and e), as well as compact electron-dense nondiscrete scrolls (f). Representative results are shown. (Original magnifications: a, ×9,000; b, ×20,000; c, ×20,000; d, ×6,000; e, ×16,000; f, ×22,000.)

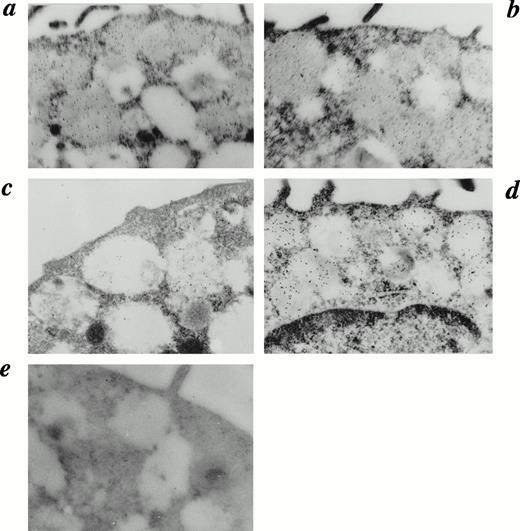

We finally examined electron microscopic immunocytochemistry using MoAb specific for human tryptase or chymase. The same level of the immunogold accumulation was detected in the granules of mast cells with or without IL-4 treatment when MoAb to human tryptase was used (Fig 4a and b). In contrast, in many mast cells cultured with IL-4, chymase reactivity was highly positive in granules compared with those of IL-4–nontreated mast cells (Fig 4c and d). These data are consistent with the results obtained by light microscopic observation and protease activity assay in which IL-4 increases MCTChigh. Taken together, these results indicated that IL-4 promotes the development of MCTChigh, which accompanied morphological maturation of the cells.

Detection of chymase and tryptase in HCMCs by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry of tryptase and chymase was performed on HCMCs cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL) for 28 days in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL). The mast cell cultured without IL-4 stained with antitryptase (a) shows the same reactivity as the mast cell cultured with IL-4 (b). In contrast, the mast cell cultured without IL-4 stained with antichymase (c) shows weak reactivity compared with the mast cell cultured with IL-4 (d). Immunocytochemical control treated with mouse IgG1 instead of antitryptase or antichymase is shown (e). Representative results are shown. (Original magnification × 30,000.)

Detection of chymase and tryptase in HCMCs by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry of tryptase and chymase was performed on HCMCs cultured with or without IL-4 (10 ng/mL) for 28 days in the presence of SCF (100 ng/mL) and IL-6 (80 ng/mL). The mast cell cultured without IL-4 stained with antitryptase (a) shows the same reactivity as the mast cell cultured with IL-4 (b). In contrast, the mast cell cultured without IL-4 stained with antichymase (c) shows weak reactivity compared with the mast cell cultured with IL-4 (d). Immunocytochemical control treated with mouse IgG1 instead of antitryptase or antichymase is shown (e). Representative results are shown. (Original magnification × 30,000.)

DISCUSSION

In this report, we showed that IL-4 promoted the development of MCTChigh in HCMCs accompanied by morphological maturation of the cells. Immunocytochemical staining showed that IL-4 increased the percentage of MCTChigh in HCMCs from 2.5% to 93.5%. Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry also confirmed this result. Consistently, activity of chymase was significantly higher in IL-4–treated mast cells than in IL-4–nontreated mast cells, whereas the activity of tryptase and histamine content in both cells were comparable. Remarkably, along with the increase of chymase expression in HCMCs by IL-4, these cells achieved morphological maturity.

It has remained unknown whether two phenotypes of human mast cells, MCT and MCTC, develop from common precursor cells or whether they are derived from two different precommitted cells. K. Tsuji (Department of Clinical Oncology, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo) and T. Nakahata (unpublished data) have observed that both MCT and MCTC were found in the same colony derived from a single cord blood CD34+ cell, suggesting that MCT and MCTC develop from common precursor cells. In the murine system, it is known that two phenotypes of murine mast cells (mucosal-type mast cells and connective tissue-type mast cells) expressing different sets of protease are derived from common precursor cells,30-32 and that final stages of mast cell differentiation are regulated by cytokines in the tissue microenvironment.23-32 Although it has been currently unknown whether MCT can differentiate into MCTC, or vice versa, development of MCTC via MCT is possible by the observation that tryptase single positive cells first appeared at week 2 of the culture and tryptase chymase double positive cells at week 7 of the culture by weekly analysis of cultured mast cells grown from cord blood CD34+cells.10 Consistently, there is a report that tissue mast cells in neonates and fetus contain a less amount, if any, of chymase than the mast cells in adults, instead of comparable levels of histamine and tryptase content with those in adult mast cells.39 Thus, although the possibility that the divergent pathways of differentiation of MCTC and MCTcannot be thoroughly excluded, these observations may suggest a linear pathway of development of MCTC cells through the MCT stage.

Consistent with this hypothesis, we showed here that IL-4–induced development of MCTChigh was accompanied by morphological maturation of the cells. Previously, Dvorak et al11-14 reported by sequential ultrastructural studies of human cord-blood–derived mast cells cultured with 3T3 fibroblasts that immature cultured mast cells contained fewer granules, which were empty or partially filled with particles in the earliest mast cells and later with scrolls, like immature mast cells in situ. While maturing, these cultured mast cells have numerous small, dense granules like those most frequently present in human skin mast cells.11-14 Based on this granule-filling criteria, Mitui et al7 showed that human mast cells developed from cord blood cells by SCF did not reach full maturity even after a 14-week culture, and furthermore, the majority of them expressed tryptase but not chymase. Consistently, in our observation, the morphology of the HCMCs cultured only with SCF and IL-6, which predominated MCT and MCTClow and contained many empty or partially filled granules, corresponded to the morphology of immature type mast cells, whereas the morphology of the HCMCs cultured with IL-4, which predominated MCTChigh and contained numerous crystal granules, corresponded to that of mature mast cells. Thus, these results indicated that immature mast cells expressed tryptase alone, and as the cells matured, they produced both tryptase and chymase. In this context, it is suggested that IL-4 promotes maturation of human mast cells that produce both tryptase and chymase.

Mast cell chymase is a serine protease, which has important proinflammatory effects. Chymase has been shown to rapidly convert angiotensin I to angiotensin II four times more efficiently than angiotensin-converting enzyme.41-43 Angiotensin II has an important effect on regulation of microcirculation including contraction of smooth muscle44 and enhancement of vascular permeability in vitro.45 Chymase also attacks the lamina lucida of the basement membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction of human skin46 causing recruitment of inflammatory cells into epidermis. The importance of mast cell chymase for allergic disorder was further shown by the genetic association between variants of mast-cell chymase gene and onset of eczema.47 Thus, increased production and release of such an active protease from activated mast cells with other vasoactive mediators may efficiently contribute to amplification of allergic reaction. Because IL-4 is known to play an important role in the onset of allergic disorder by increasing IgE production by B cells and because increased IL-4 production by T cells from allergic patients has been reported,48 49 our observation that IL-4 increases the content of chymase in human mast cells may have a significant meaning in the enhancement of allergic inflammation.

As shown in this report and others,7,33,35,50HCMCs grown from cord blood mononuclear cells in the presence of SCF have been shown to have many immature features including low expression of FcεRI, low histamine releasing activity, and the immature morphology shown by the ultrastructural analysis, although they express c-kit and contain a significant amount of tryptase and histamine. We and others have previously shown that IL-4 promotes maturation and differentiation of human mast cells in several aspects. IL-4 induces FcεRI expression in HCMCs as well as in murine mast cells, resulting in high histamine-releasing activity on crosslinking of FcεRI.33,51 IL-4 suppresses c-kit expression35,37 and also strongly induces LFA-1 and ICAM-1 expression.35 36 In this report, we have shown that IL-4 promotes morphological maturation of HCMCs in accordance with the increase of chymase expression. Taken together, all these observations would suggest that IL-4 is a key factor for human mast cell differentiation and maturation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr H. Ishida for providing cytokines, M. Toriyama and I. Tanaka for technical assistance, and Drs S. Sasaki, I. Kamiyama, and the staff of Matsushima Obstetric and Pediatric Hospital for providing human cord blood. We thank Dr S. Nonoyama for critical review of the manuscript.

Address reprint requests to Hano Toru, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Yushima 1-5-45, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113, Japan.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.