Abstract

Primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) are potential targets for treatment of numerous hematopoietic diseases using retroviral-mediated gene transfer (RMGT). To achieve high efficiency of gene transfer into primitive HPCs, a delicate balance between cellular activation and proliferation and maintenance of hematopoietic potential must be established. We have demonstrated that a subpopulation of human bone marrow (BM) CD34+ cells, highly enriched for primitive HPCs, persists in culture in a mitotically quiescent state due to their cytokine-nonresponsive (CNR) nature, a characteristic that may prevent efficient RMGT of these cells. To evaluate and possibly circumvent this, we designed a two-step transduction protocol usingneoR-containing vectors coupled with flow cytometric cell sorting to isolate and examine transduction efficiency in different fractions of cultured CD34+ cells. BM CD34+ cells stained on day 0 (d0) with the membrane dye PKH2 were prestimulated for 24 hours with stem cell factor (SCF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), and IL-6, and then transduced on fibronectin with the retroviral vector LNL6 on d1. On d5, half of the cultured cells were transduced with the retroviral vector G1Na and sorted on d6 into cytokine-responsive (d6 CR) cells (detected via their loss of PKH2 fluorescence relative to d0 sample) and d6 CNR cells that had not divided since d0. The other half of the cultured cells were first sorted on d5 into d5 CR and d5 CNR cells and then infected separately with G1Na. Both sets of d5 and d6 CR and CNR cells were cultured in secondary long-term cultures (LTCs) and assayed weekly for transduced progenitor cells. Significantly higher numbers of G418-resistant colonies were produced in cultures initiated with d5 and d6 CNR cells compared with respective CR fractions (P < .05). At week 2, transduction efficiency was comparable between d5 and d6 transduced CR and CNR cells (P > .05). However, at weeks 3 and 4, d5 and d6 CNR fractions generated significantly higher numbers ofneoR progenitor cells relative to the respective CR fractions (P < .05), while no difference in transduction efficiency between d5 and d6 CNR cells could be demonstrated. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the origin of transducedneoR gene in clonogenic cells demonstrated that mature progenitors (CR fractions) contained predominantly LNL6 sequences, while more primitive progenitor cells (CNR fractions) were transduced with G1Na. These results demonstrate that prolonged stimulation of primitive HPCs is essential for achieving efficient RMGT into cells capable of sustaining long-term in vitro hematopoiesis. These findings may have significant implications for the development of clinical gene therapy protocols.

HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS, due to their long-term engraftment potential, are the target cells of choice in somatic gene therapy for malignant and nonmalignant bone marrow (BM) disorders.1-3 Retroviral-mediated gene transfer (RMGT) remains the most attractive means of reliably delivering genetic material to cells possessing high proliferative potential.4-6 The major limitation of RMGT is the requirement for cell division before stable integration of the retroviral vector into the target cell genome.7 Since “true” stem cells represent a relatively quiescent population of hematopoietic cells,8-11 transduction efficiency into these cells without cytokine stimulation is low. However, cytokine stimulation of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) may compromise the hematopoietic potential of these cells, since in vitro activation of HPCs is normally associated with progressive loss of self-renewal capacity and increased lineage commitment.12-16 Nevertheless, cytokine stimulation has been shown to increase gene transduction efficiency into human committed BM progenitors.17,18 In addition, stable engraftment of retrovirally marked human BM cells in immunodeficient mice19,20 or in clinical gene-marking studies21 22 suggests transfer of foreign genetic material into human stem cells.

Recently, our laboratory documented the persistence of a cytokine nonresponsive (CNR) population of HPCs in short-term cultures and demonstrated the ability of these cells to sequentially enter the cell cycle and proliferate.23,24 Furthermore, human CNR cells were shown to be enriched for long-term hematopoietic culture-initiating cells,23 and in the murine system were capable of repopulating the hematopoietic system of lethally irradiated recipients.25 The identification of CNR cells,23 which resemble those described by Berardi et al26 as a group of cells highly enriched for primitive HPCs, raises the question of whether prestimulation of human CD34+ cells for a relatively short period pre-RMGT facilitates gene transduction into mature elements of the progenitor pool but not into the more primitive, mitotically dormant cells. In support of this contention are the recent studies by Larochelle et al,20 which demonstrated that although high-efficiency gene transfer into mature and primitive clonogenic cells was achieved by a short prestimulation of CD34+ cells followed by RMGT over recombinant fragments of the extracellular matrix component, fibronectin, gene transfer into more primitive NOD/SCID repopulating cells was inefficient.20

Given these observations regarding the nature of CNR cells and the relative inefficiency of transducing primitive HPCs, we reasoned that RMGT into cells capable of sustaining prolonged in vitro hematopoiesis may be enhanced if CNR cells were specifically targeted via prolonged cytokine stimulation and delayed transduction. In this study, we transduced BM CD34+ cells at 1, 5, and 6 days after cytokine stimulation in short-term culture and examined the contribution of each transduction cycle to gene transfer efficiency in CNR cells and to the persistence of long-term expression of transduced genes. We report here that transduction on day 5 (d5) or d6, but not on d1, resulted in efficient gene transfer into CNR cells, and that only this fraction of cultured cells was capable of supporting the production of transduced progenitors for up to 5 weeks. These results suggest that efficient RMGT into hematopoietic cells may be best realized by delayed targeting of quiescent primitive HPCs. Furthermore, our findings define fractions of ex vivo manipulated CD34+cells that may be responsible for long-term expression of transduced genetic material and offer potential alternatives for improving somatic gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BM collection and fractionation.

Human BM aspirates were collected from normal adult subjects after obtaining informed consent according to guidelines established by the Investigational Review Board of Indiana University School of Medicine. Low-density BM cells were recovered by Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) density centrifugation. Cells were fractionated by immunomagnetic selection to obtain CD34+ cells as previously described.23 27 All reagents for the immunomagnetic separation procedure were kindly provided by Baxter Healthcare (Irvine, CA).

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometric cell sorting.

Immunomagnetically enriched BM CD34+ cells were stained on ice for 20 minutes with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD34 (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems [BDIS], San Jose, CA). Control monoclonal antibodies consisted of fluorochrome-conjugated, isotype-matched, nonspecific myeloma proteins. Cells were washed and resuspended for flow cytometric cell sorting in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 1% human serum albumin and were immediately sorted as previously described23 28 on a FACStarplus flow cytometer (BDIS). Viability and purity of sorted cells always exceeded 98% and 90%, respectively.

PKH2 staining.

Sorted CD34+ cells were stained with PKH2 (Sigma ImmunoChemicals, St Louis, MO) before use in short-term culture, per the manufacturer's instructions and as previously described.23 Briefly, cells were suspended in 1 mL diluent (Sigma Immuno Chemical) and immediately transferred into a polypropylene tube containing 1 mL 4 × 10−6-mol/L PKH2 in diluent at room temperature. After 5 minutes of incubation with frequent agitation, 2 mL fetal calf serum ([FCS] Hyclone, Logan, UT) was added to the suspension for 1 minute. The total volume was brought to 8 mL with Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% FCS, L-Glutamine, and antibiotics (complete medium), and the cells were washed three times in complete medium. All of the complete medium ingredients (except FCS) were obtained from BioWhitaker (Walkersville, MD). Antibiotics consisted of penicillin and streptomycin at 100 U/mL and 100 mg/mL, respectively. After the last wash, cells were suspended in complete medium and cultured with cytokines as described later. The validity of the PKH2 staining method on human BM cells has been previously established.29

Preparation of fibronectin-coated dishes.

Non–tissue culture-grade culture dishes were coated with fibronectin according to Moritz et al.30 Briefly, the wells were coated for 2 hours at room temperature with a 30/35-kD protein fragment at a concentration of 10 μg/cm2 in PBS. Excess protein solution was aspirated, and the remaining free sites were blocked with 0.5 mL 2% fibronectin-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. Excess BSA solution was aspirated, and the wells were washed with Hanks' balanced salt solution supplemented with HEPES buffer.

Retroviral vectors.

The two recombinant retroviral vectors used in these studies were LNL6 and G1Na, both of which contained the gene for neomycin resistance (neoR). The LNL6 vector, which is amphotropically packaged in the PA317 cell line and has a titer of 1 to 2 × 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL, was developed by Bender et al.31 The G1Na vector was developed by Genetic Therapy (Gaithersburg, MD) and is packaged in the PA317 cell line. Similar to LNL6, G1Na also has a titer of 1 to 2 × 106 CFU/mL. Both vectors were negative for replication-competent retrovirus when tested in the S+/L− assay.32 Fresh filtered (0.45 μm) supernatant was used for each assay.

Retroviral transduction.

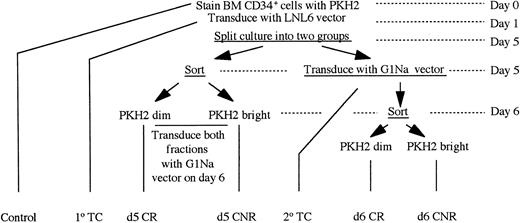

PKH2-stained BM CD34+ cells were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2 with 100 ng/mL each of stem cell factor (SCF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), and IL-6. Cells were transduced the next day (d1) by incubating overnight with LNL6 or G1Na viral supernatant at a multiplicity of infection (moi) greater than 10:1 on plates coated with fibronectin, in the presence of 8 μg/mL Polybrene and cytokines. Following infection, nonadherent cells were collected in IMDM supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum while the adherent cells were treated with 0.5% trypsin-EDTA. Cells were washed twice with medium and replated with cytokines in tissue culture–grade flat-bottomed 48-well plates in the absence of fibronectin. On d5, cells were harvested and split into two parts. Half of the cells were washed and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated CD34 and sorted to yield CD34+ PKH2bright (CNR) and CD34+PKH2dim (cytokine-responsive [CR]) cells as previously demonstrated.23 A sample fixed in 1% formaldehyde on d0 immediately after staining of fresh sorted CD34+ cells with PKH2 was used to establish PKH2 fluorescence corresponding to nondividing cells. Stringent selection of CNR cells based on PKH2 fluorescence was performed according to previously established procedures.23,28 29 Fractions isolated on d5 are referred to as d5 CNR and d5 CR fractions (Fig 1). These fractions were cultured overnight in the presence of SCF, IL3, and IL6 and were then transduced on d6 with G1Na or LNL6 supernatant (using whichever vector was not used on d1) on fibronectin-coated dishes (plus Polybrene) overnight as on d1. These cells were subsequently washed and plated in individual wells of a 48-well plate with SCF, IL-3, and IL-6. The remaining half of the cells were transduced on day 5 with G1Na or LNL6 supernatant (using whichever vector was not used on day 1) on fibronectin-coated dishes plus Polybrene overnight, and then trypsinized, harvested, washed, and stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD34 on d6. The same strategy used on d5 was applied again to isolate CD34+PKH2bright (CNR) and CD34+ PKH2dim(CR) cells. Since these fractions were isolated on d6, they are referred to as d6 CNR and d6 CR fractions (Fig1). After isolation, d6 CNR and d6 CR cells were plated in individual wells of a 48-well plate with SCF, IL-3, and IL-6.

Schema of the experimental design used for transducing CNR cells on d5 and d6. A total of 6 experiments were performed for these studies. In 4, the retroviral vector LNL6 was used on d1 and the vector G1Na on d5 and d6. In the other 2 experiments, the sequence was reversed. The schema presented here depicts the sequence of experimental steps used when cells were transduced with LNL6 on d1 and with G1Na on d5 and d6.

Schema of the experimental design used for transducing CNR cells on d5 and d6. A total of 6 experiments were performed for these studies. In 4, the retroviral vector LNL6 was used on d1 and the vector G1Na on d5 and d6. In the other 2 experiments, the sequence was reversed. The schema presented here depicts the sequence of experimental steps used when cells were transduced with LNL6 on d1 and with G1Na on d5 and d6.

Control long-term cultures (LTCs) maintained along with those established with d5 and d6 CNR and CR cells included the following: a control LTC established on d1 with unmanipulated, mock-infected CD34+ cells to evaluate the effect of gene transfer on the ability of normal CD34+ cells to sustain in vitro hematopoiesis; a primary transduction control (1° TC) LTC initiated with cells transduced on d1 and not subjected to any further fractionation on d5 or d6; and a secondary transduction control (2° TC) culture initiated with a sample of total CD34+ cells removed after d5 transduction and before further fractionation of these cells on d6 (Fig 1).

LTC.

Secondary LTCs of the fractions (control and transduced) were established in 1 mL complete medium in flat-bottomed 48-well plates as described previously.13 23 Secondary cultures were supplemented at initiation and every 48 hours thereafter with 100 ng/mL each of SCF, IL-3, and IL-6. At weekly intervals, cultures were demidepopulated and the remaining cells were replenished with fresh medium and cytokines. Collected cells were used in HPC assays. For ease of data presentation, results obtained from cultures established with control, 1° TC, and 2° TC cells will not be presented in every figure.

HPC assay.

A total of 103 fresh CD34+ cells or between 2 and 8 × 103 cultured cells were suspended in 35-mm tissue culture dishes in 1 mL containing 30% FCS, 5 × 10−5mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 ng/mL SCF, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 10 ng/mL IL-6, 5 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, 2 U/mL erythropoietin, and 1.1% methylcellulose in IMDM. All cytokines used in these studies were a kind gift from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Duplicate cultures with and without G418 (Sigma) prepared at 1 mg/mL (active compound) were established. Cultures were incubated in 100% humidified 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. Burst forming units-erythroid, CFU-granulocyte-macrophage, or CFU-granulocyte-erythroid-macrophage-megakaryocyte detected in the presence or absence of G418 were enumerated on d14 using an inverted microscope. Between 7 and 15 G418-resistant individual hematopoietic colonies were plucked aseptically and analyzed for the presence of theneoR gene by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Transduction efficiency was defined as (no. of G418-resistant colonies/no. of cells plated in G418) × (no. of cells plated without G418 × 100/no. of unselected colonies).

PCR analysis.

Individual colonies were identified and isolated into microcentrifuge tubes containing 500 mL PBS. DNA from each colony was extracted as follows. Cells were pelleted at 2,000g for 7 to 8 minutes at 4°C. All of the supernatant was removed, and the cells were suspended in 40 μL water. Samples were incubated initially for 10 minutes at 94°C, then at 55°C for 1 hour after addition of 20 μg proteinase K (Sigma), and finally at 94°C for 15 minutes. DNA extracted from each colony was split into two parts and tested for the presence of theneoR gene with two sets of primers specific for PA317/LNL6 and PA317/G1Na to distinguish the source of theneoR sequence. The neomycin phosphotransferase gene from vector G1Na was amplified using the primers 5′ GAATTCGCGGCCGCTACAAT 3′ and 5′ GATAGAAGGCGATGCGCTGC 3′ while the same gene from the LNL6 vector was amplified using the primers 5′ GGTTGGGCTTCGGAATCGTT 3′ and 5′ TCTACACTGGCTCGATGGAG 3′. DNA amplification was performed with a Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, CT) thermal cycler for 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 minute, 65°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute. PCR products were separated on 1.7% agarose gels (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), transferred to nylon membranes (Midwest Scientific, St Louis, MO), and hybridized to a 32P-labeledEcoRI-Sal I fragment of pLNL6 DNA. Prehybridization, hybridization, and posthybridization washes were performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Statistical analysis.

Where applicable, data are presented as the mean ± SE. In some figures and for clarity of presentation, only the positive SE is depicted. Statistical comparison between paired data from different groups was performed using a two-tailed t-test.

RESULTS

Evaluation of gene transfer efficiency of LNL6 and G1Na.

To follow retroviral-marked cells in culture, we selected the LNL6 and G1Na vectors that contain the neoR gene. The structure of the vectors is similar except for the noncoding region 3′ to the neoR gene. This sequence difference permits the design of vector-specific PCR primers capable of distinguishing the respective vectors. Since the LNL6 and G1Na producer cell lines generate vector at similar titers (1 to 2 × 106CFU/mL), these vectors are predicted to transduce target cells at similar efficiencies. It was therefore essential to compare and confirm the transduction efficiency of both vectors. BM CD34+ cells prestimulated overnight were transduced on d1 with fresh G1Na and LNL6 viral supernatants. Transduction efficiencies of both groups of transduced CD34+ cells were similar (19.6% and 22.5% for G1Na and LNL6, respectively, n = 2) indicating that G1Na and LNL6 were equally capable of transducing primary BM CD34+ cells.

Susceptibility of different fractions of cultured CD34+cells to G1Na and LNL6.

Since the experimental design involved transduction of different fractions of ex vivo–expanded CD34+ cells with G1Na or LNL6 at different time points, we investigated the susceptibility of these cell fractions to both retroviruses. Total BM CD34+cells were stained with PKH2 and cultured with SCF, IL3, and IL6, and on d1, d5, d6, d8, or d9 were transduced with G1Na or LNL6 supernatant. To distinguish between the susceptibility of fractions of cultured cells to transduction before and after fractionation, two different approaches were taken. In the first, cultured CD34+ cells were separated on d5 and d8 into CNR and CR cells (based on residual PKH2 fluorescence) and both CNR and CR cells were split into two fractions, each of which was then transduced with one of the two retroviral vectors. In the second, cultured CD34+ cells were first transduced on d6 and d9 and then fractionated into CNR and CR cells. The data presented in Table 1demonstrate that at any given time point, all groups of cells were equally transduced with either G1Na or LNL6. It is evident that regardless of whether cells were exposed to vector before or after fractionation into CR and CNR cells, these fractions were equally susceptible to transduction with G1Na and LNL6, and that the highest degree of gene transfer occurred on d5 and d6 (Table 1). It is important to point out that on d8 and d9, CNR fractions produced a higher number of total and G418-resistant colonies compared with their respective CR counterparts, suggesting that targeting CNR fractions may be essential to achieve efficient RMGT in cells enriched for enhanced progenitor cell production capacity and possibly primitive hematopoietic potential.

Targeting of CNR cells with RMGT.

Based on the preliminary data shown in Table 1, it was reasoned that effective gene transfer into CNR cells could be achieved after 5 to 6 days of in vitro prestimulation. Experiments designed to examine this possibility and to investigate whether transduced CNR cells could support the long-term production of marked progenitor cells in vitro were performed according to the schema outlined in Fig 1. A total of six experiments were performed. In four, LNL6 was used on d1 and G1Na on d5 and d6, while the sequence was reversed in the other two experiments. All resulting groups of cells were maintained in suspension LTC, and the production of total and G418-resistant clonogenic progenitor cells was assessed.

As previously demonstrated in prior reports from our laboratory,23,24 33 the overall production of assayable progenitor cells in cultures initiated with d5 or d6 CNR cells exceeded that detected in cultures initiated at the same time points with CR cells or transduction control cultures (2° TC) established on d5 (Fig2A). Not only did LTCs initiated with d5 CNR and d6 CNR cells produce significantly more (P < .05) clonogenic cells at weeks 3 and 4 than cultures initiated with cells from other groups (d5 CR, d6 CR, and 2° TC), production of CFU in these cultures was sustained for a longer period than in other cultures (Fig 2A). Of interest is that the peak production of assayable progenitors and the magnitude of CFU production at every time point analyzed were matched closely in cultures established with d5 CNR and d6 CNR cells, suggesting that differences in the sequence of experimental steps used to isolate these two groups of cells had no adverse effects on their hematopoietic potential.

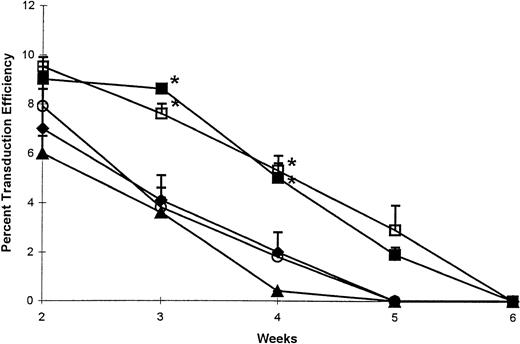

Total assayable (A) and G418-resistant (B) progenitor cells produced in long-term hematopoietic cultures initiated with 5 groups of transduced CD34+ cells as outlined in Fig 1. Cells isolated as d5 CR (⧫), d5 CNR (▪), d6 CR (○), or d6 CNR (□) or maintained as 2° TC (▴) were used to establish LTCs supplemented with cytokines. Cultures were demidepopulated every week, followed by replenishment of half of the medium and cytokines. Harvested cells were used for clonogenic assays in the presence or absence of G418. For clarity and ease of presentation, data from each of the 5 groups of cells are presented as the mean ± SE of assayable and G418-resistant clonogenic cells detected at the indicated time points in 6 separate LTCs initiated with BM cells from 6 different normal donors. Values were normalized to represent data obtained from cultures initiated with 104 cells. In 4 experiments, LNL6 was used on d1 and G1Na on d5 and d6, while the reverse order was used in the remaining 2 experiments. *P < .05, the indicated CNR group v the respective CR group. At weeks 3 and 4, d5 CNR and d6 CNR values (in A and B) were also statistically different (P < .05) from those observed in 2° TC. No significant differences were detected between d5 and d6 CNR cells.

Total assayable (A) and G418-resistant (B) progenitor cells produced in long-term hematopoietic cultures initiated with 5 groups of transduced CD34+ cells as outlined in Fig 1. Cells isolated as d5 CR (⧫), d5 CNR (▪), d6 CR (○), or d6 CNR (□) or maintained as 2° TC (▴) were used to establish LTCs supplemented with cytokines. Cultures were demidepopulated every week, followed by replenishment of half of the medium and cytokines. Harvested cells were used for clonogenic assays in the presence or absence of G418. For clarity and ease of presentation, data from each of the 5 groups of cells are presented as the mean ± SE of assayable and G418-resistant clonogenic cells detected at the indicated time points in 6 separate LTCs initiated with BM cells from 6 different normal donors. Values were normalized to represent data obtained from cultures initiated with 104 cells. In 4 experiments, LNL6 was used on d1 and G1Na on d5 and d6, while the reverse order was used in the remaining 2 experiments. *P < .05, the indicated CNR group v the respective CR group. At weeks 3 and 4, d5 CNR and d6 CNR values (in A and B) were also statistically different (P < .05) from those observed in 2° TC. No significant differences were detected between d5 and d6 CNR cells.

Similarly, production of G418-resistant CFU was highest in LTCs initiated with either d5 CNR or d6 CNR cells (Fig 2B). Also of interest is that the peak production of G418-resistant progenitor cells (Fig 2B) coincided with the peak production of clonogenic cells (Fig 2A). At week 3, a slightly higher but statistically insignificant number of transduced progenitors were detected in d5 CNR cultures compared with d6 CNR cultures (Fig 2B). Only those two LTCs contained transduced progenitors at week 5, albeit in small numbers. None of the LTCs that sustained in vitro hematopoiesis beyond week 5 contained any transduced progenitors at week 6.

Transduction efficiency.

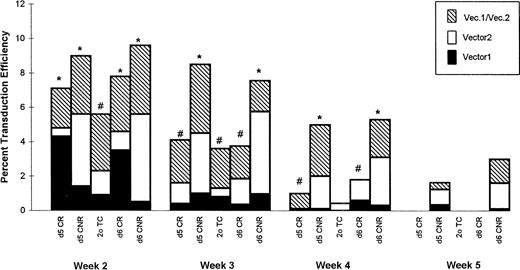

Due to the large number of transduced cells required for assay in the presence of G418 and to the limited number of cells available at the end of week 1, we opted not to examine any of the infected groups of cells at this time point. However, transduction efficiency in all of the groups analyzed was highest at week 2, yet at this time point, no significant differences (P > .05) in transduction efficiency between d5 and d6 CNR fractions and their CR counterparts could be established (Fig 3). As predicted from the production of transduced clonogenic cells (Fig 2B), transduction efficiency in cultures established with d5 CR, d6 CR, or 2° TC cells declined drastically by weeks 3 and 4. In contrast, only a slight decline in transduction efficiency was observed between weeks 2 and 3 in cultures established with d5 and d6 CNR cells. This initial maintenance of transduction efficiency in these cultures was followed by a rapid decrease between weeks 3 and 5 (Fig 3). During weeks 3 and 4, transduction efficiency was significantly higher in d5 and d6 CNR cultures (P < .05) compared with their respective CR counterparts and 2° TC cultures. Again, of interest are the analogous transduction efficiencies observed in cultures initiated with either d5 CNR or d6 CNR cells, suggesting that differences in the methodology used in isolating these cells did not negatively affect the hematopoietic function of either fraction.

Transduction efficiency detected in long-term hematopoietic cultures initiated with 5 groups of transduced CD34+ cells as outlined in Fig 1. Cells isolated as d5 CR (⧫), d5 CNR (▪), d6 CR (○), and d6 CNR (□) or maintained as 2° TC (▴) were used to establish LTCs supplemented with cytokines. Cultures were demidepopulated every week, followed by replenishment of half of the medium and cytokines. Harvested cells were used for clonogenic assays in the presence or absence of G418. For every time point, transduction efficiency was calculated as (no. of G418-resistant colonies/no. of cells plated in G418) × (no. of cells plated without G418 × 100/no. of unselected colonies). For clarity and ease of presentation, data from each of the 5 groups of cells are presented as the mean ± SE of transduction efficiency calculated at each indicated time point in 6 separate LTCs initiated with BM cells from 6 different normal donors. *P < .05, the indicated CNR group vthe respective CR group. At weeks 3 and 4, d5 CNR and d6 CNR values were also statistically different (P < .05) from those observed in 2° TC. No significant differences were detected between d5 and d6 CNR cells at any time point.

Transduction efficiency detected in long-term hematopoietic cultures initiated with 5 groups of transduced CD34+ cells as outlined in Fig 1. Cells isolated as d5 CR (⧫), d5 CNR (▪), d6 CR (○), and d6 CNR (□) or maintained as 2° TC (▴) were used to establish LTCs supplemented with cytokines. Cultures were demidepopulated every week, followed by replenishment of half of the medium and cytokines. Harvested cells were used for clonogenic assays in the presence or absence of G418. For every time point, transduction efficiency was calculated as (no. of G418-resistant colonies/no. of cells plated in G418) × (no. of cells plated without G418 × 100/no. of unselected colonies). For clarity and ease of presentation, data from each of the 5 groups of cells are presented as the mean ± SE of transduction efficiency calculated at each indicated time point in 6 separate LTCs initiated with BM cells from 6 different normal donors. *P < .05, the indicated CNR group vthe respective CR group. At weeks 3 and 4, d5 CNR and d6 CNR values were also statistically different (P < .05) from those observed in 2° TC. No significant differences were detected between d5 and d6 CNR cells at any time point.

PCR analysis of G418-resistant colonies.

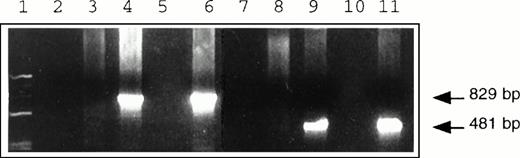

The design of these experiments necessitated that the primers used to amplify LNL6 and G1Na sequences be specific for their respective retroviral vectors and capable of determining the origin of theneoR gene in transduced cells. DNA extracted from individual hematopoietic colonies was amplified with G1Na-specific and LNL6-specific primer pairs separately or together. Only DNAs amplified by the appropriate primer sets were detected, thus confirming the specificity of the primers used (Fig4). We next examined the fidelity of our PCR assay by investigating whether PCR analysis of cells exposed to both LNL6 and G1Na at different time points was capable of identifying the origin of the transducedneoR gene. Figure 5demonstrates that HPCs successfully transduced with both vectors displayed the two vector-specific sequences, while those successfully transduced with only one of the two vectors contained sequences corresponding to the appropriate vector.

PCR amplification of genomic DNA isolated from individualneoR hematopoietic colonies transduced with G1Na (lanes 3, 4, and 6) and LNL6 (lanes 8, 9, and 11) vectors. Samples were subjected to 30 cycles of amplification using primer pairs specific for G1Na (lanes 4 and 8), LNL6 (lanes 3 and 9), or both (lanes 6 and 11). Ethidium bromide–stained products of 829-bp and 481-bp DNA sequences indicate specific amplification by G1Na- and LNL6-specific primers, respectively. Molecular weight markers were loaded in lane 1, and lanes 2, 5, 7, and 10 were blank.

PCR amplification of genomic DNA isolated from individualneoR hematopoietic colonies transduced with G1Na (lanes 3, 4, and 6) and LNL6 (lanes 8, 9, and 11) vectors. Samples were subjected to 30 cycles of amplification using primer pairs specific for G1Na (lanes 4 and 8), LNL6 (lanes 3 and 9), or both (lanes 6 and 11). Ethidium bromide–stained products of 829-bp and 481-bp DNA sequences indicate specific amplification by G1Na- and LNL6-specific primers, respectively. Molecular weight markers were loaded in lane 1, and lanes 2, 5, 7, and 10 were blank.

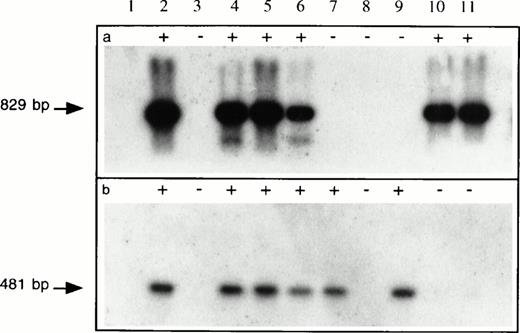

PCR analysis of hematopoietic progenitor colonies transduced with G1Na and LNL6 retroviral vectors. DNA samples isolated at week 2 posttransduction from 10 representativeneoR hematopoietic colonies (lanes 2 through 11) from human BM CD34+ cells transduced with G1Na on d1 followed by LNL6 on d5 were subjected to PCR analysis using G1Na-specific (a) or LNL6-specific (b) primer pairs. The products of PCR amplification were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel and visualized on Southern blots using 32P-labeledneo-specific sequences. While 4 colonies (lanes 2, 4, 5, and 6) showed the presence of both retroviral vectors, 2 colonies each (lanes 7 and 9 and lanes 10 and 11), respectively, showed sequences specific for either LNL6 or G1Na vectors alone. Lane 1 is a negative control. PCR amplification of DNA obtained from 2 colonies (lanes 3 and 8) was not successful.

PCR analysis of hematopoietic progenitor colonies transduced with G1Na and LNL6 retroviral vectors. DNA samples isolated at week 2 posttransduction from 10 representativeneoR hematopoietic colonies (lanes 2 through 11) from human BM CD34+ cells transduced with G1Na on d1 followed by LNL6 on d5 were subjected to PCR analysis using G1Na-specific (a) or LNL6-specific (b) primer pairs. The products of PCR amplification were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel and visualized on Southern blots using 32P-labeledneo-specific sequences. While 4 colonies (lanes 2, 4, 5, and 6) showed the presence of both retroviral vectors, 2 colonies each (lanes 7 and 9 and lanes 10 and 11), respectively, showed sequences specific for either LNL6 or G1Na vectors alone. Lane 1 is a negative control. PCR amplification of DNA obtained from 2 colonies (lanes 3 and 8) was not successful.

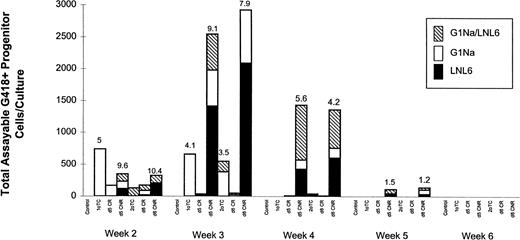

Individual colonies obtained from the progenitor cell assays performed weekly on all fractions maintained in LTC were used for PCR analysis to test for the presence and determine the origin of the transducedneoR gene. Figure 6depicts PCR analysis results from individual colonies obtained from one experiment in which CD34+ cells were transduced on d1 with G1Na supernatant and on d5 and d6 with LNL6 supernatant. Figure 6demonstrates that only cultures initiated with d5 CNR or d6 CNR cells contained a significant number of G418-resistant progenitors at weeks 3 and 4. PCR analyses for determination of the origin of theneoR gene in individual colonies showed that cells isolated from colonies produced in cultures initiated with 1° TC cells contained G1Na sequences only (Fig 6). At weeks 3 and 4, the highest transduction efficiency was detected in cultures established with d5 or d6 CNR cells. Close analysis of the origin ofneoR sequences showed that the majority of progenitors were transduced on d5 or d6 with the LNL6 vector (Fig 6). However, a sizable fraction of transduced progenitors in d5 and d6 CNR cultures expressed both G1Na and LNL6 sequences. By week 5, only d5 CNR and d6 CNR cultures contained any transduced progenitor cells, albeit at a substantially low frequency relative to that recorded at weeks 3 and 4.

PCR analysis from 1 representative long-term hematopoietic culture initiated with all 7 groups of transduced and untransduced CD34+ cells outlined in Fig 1. In this experiment, cells were transduced on d1 with G1Na and with LNL6 on d5 and d6. LTCs were initiated on d0, d1, d5, or d6 with the indicated cell group and maintained with cytokines. Cultures were demidepopulated every week, followed by replenishment of half of the medium and cytokines. Harvested cells were used for clonogenic assays in the presence or absence of G418. Values were normalized to represent data obtained from cultures initiated with 104 cells. The origin of the neoR gene detected in single colonies at weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5 is indicated. Each bar is divided into 3 sections reflecting the percentage of colonies at each time point containing G1Na sequences, LNL6 sequences, or both. For every data point, between 7 and 15 colonies were analyzed. Numbers on top of each bar indicate the transduction efficiency. Similar results were obtained in 1 additional experiment using this sequence of transduction.

PCR analysis from 1 representative long-term hematopoietic culture initiated with all 7 groups of transduced and untransduced CD34+ cells outlined in Fig 1. In this experiment, cells were transduced on d1 with G1Na and with LNL6 on d5 and d6. LTCs were initiated on d0, d1, d5, or d6 with the indicated cell group and maintained with cytokines. Cultures were demidepopulated every week, followed by replenishment of half of the medium and cytokines. Harvested cells were used for clonogenic assays in the presence or absence of G418. Values were normalized to represent data obtained from cultures initiated with 104 cells. The origin of the neoR gene detected in single colonies at weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5 is indicated. Each bar is divided into 3 sections reflecting the percentage of colonies at each time point containing G1Na sequences, LNL6 sequences, or both. For every data point, between 7 and 15 colonies were analyzed. Numbers on top of each bar indicate the transduction efficiency. Similar results were obtained in 1 additional experiment using this sequence of transduction.

Data from all experiments in this study were analyzed collectively and are summarized in Fig 7. In this analysis, whichever vector was used on d1 was designated as vector 1, while that used on d5 and d6 was designated vector 2. Similar to the results presented in Fig 6, analysis of the origin of neoRsequences in clonogenic cells derived from d5 and d6 CNR cells indicated that the long-term persistence of theneoR gene was due to the vector used on d5 and d6 (vector 2). Interestingly, at week 2, progenitors expressingneoR sequences derived from vector 1 appear to sequester among CR cells, while those acquired during d5 and d6 transduction (vector 2) segregate mostly among CNR cells. In fact, at weeks 3 and 4, a greater percentage of HPCs from d5 and d6 CNR cultures expressed vector 2 as compared with vector 1 sequences (P < .05). These results indicate that cells capable of sustaining long-term in vitro hematopoiesis, ie, CNR cells, are best transduced after 5 or 6 days of prestimulation. In addition, a substantial fraction of transduced progenitor cells derived from CNR cells expressed both G1Na and LNL6 sequences, indicating the possibility of transducing individual progenitor cells with two different vectors.

Summary of PCR analysis of single colonies isolated from LTCs at weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. Each bar represents the transduction efficiency calculated for a particular group of cells at a given time point calculated as the mean of 3 to 6 values detected in 6 separate experiments initiated with BM cells from 6 different normal donors. Whichever vector was used on d1 is designated vector 1, and that used on d5 and d6 is designated vector 2. Each bar is divided into 3 sections reflecting the percentage of colonies at each time point containing vector 1 sequences, vector 2 sequences, or both as defined in the legend. For every data point, between 26 and 59 colonies were analyzed. *P < .05, percentage of progenitor cells expressing vector 1–derived v vector 2–derived neoRsequences within the same group. The percentage of progenitors expressing both sequences was not considered for this analysis.#Not significant.

Summary of PCR analysis of single colonies isolated from LTCs at weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. Each bar represents the transduction efficiency calculated for a particular group of cells at a given time point calculated as the mean of 3 to 6 values detected in 6 separate experiments initiated with BM cells from 6 different normal donors. Whichever vector was used on d1 is designated vector 1, and that used on d5 and d6 is designated vector 2. Each bar is divided into 3 sections reflecting the percentage of colonies at each time point containing vector 1 sequences, vector 2 sequences, or both as defined in the legend. For every data point, between 26 and 59 colonies were analyzed. *P < .05, percentage of progenitor cells expressing vector 1–derived v vector 2–derived neoRsequences within the same group. The percentage of progenitors expressing both sequences was not considered for this analysis.#Not significant.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the results of early versus delayed RMGT into human BM CD34+ cells and evaluated the fate of transduced cells in two cell fractions discernible in culture based on their proliferative history. Whereas more mitotically active CR cells displayed a limited ability to produce assayable progenitors, cells resistant to immediate cytokine stimulation, here termed CNR cells, were responsible for the maintenance of long-term in vitro hematopoiesis and continued expression of transducedneoR genes, demonstrating successful gene transfer into primitive HPCs. Recent studies by Larochelle et al20demonstrated that exposure of human CD34+ cells to retroviral vectors efficiently transduced clonogenic progenitors and LTC-initiating cells, but not the more primitive SCID repopulating cells. These investigators20 transduced CD34+cells after 24 hours of prestimulation with SCF, IL-3, and IL-6 using a protocol that required up to 48 hours of additional in vitro incubation during which the cells were exposed to the retroviral vector. Among the possible explanations as to why SCID repopulating cells were not genetically marked is the possibility that these cells were not induced to proliferate during the 72 hours of in vitro manipulation, an event previously demonstrated to be essential for successful RMGT.7,34 This study20 and others35suggest that RMGT into quiescent primitive HPCs is not efficient if cells are exposed to the retroviral vector within 72 hours of in vitro stimulation. The failure to effectively transduce long-term marrow repopulating cells using a 3-day or shorter transduction protocol has been previously documented by several investigators.36-39

CNR23,24,28 and similar cells identified by other groups26,40,41 may remain dormant in culture for up to 10 days. In cultures of PKH2-stained CD34+ cells, CNR cells can be identified as soon as the more CR cells begin to proliferate and lose their PKH2 fluorescence. However, the relative size of the CNR cell population decreases with time. It was therefore logical to identify, isolate, and transduce CNR cells as soon as feasible to obtain the largest number of cells for these studies. In addition, preliminary results (Table 1) demonstrated that the highest transduction efficiency of total CD34+ cells and the CR and CNR fractions was possible on d5 or d6. We have previously demonstrated29 that the rate of proliferation of CR cells, measured as the percentage of cells detected in the S and G2 + M phases of the cell cycle, decreases with every additional division, suggesting that the decline in transduction efficiency observed on d8 and d9 may be the result of increased mitotic quiescence.

Of interest is that CNR cells, whether isolated from culture and then infected or infected while in culture with other cell fractions, were equally susceptible to transduction on d5 or d6. Since CNR cells most likely remained quiescent until after isolation from short-term cultures, these results suggest it is possible to achieve efficient gene transfer into quiescent cells provided these targets enter into active phases of the cell cycle within a relatively short period following delivery of foreign genetic material. This may explain the somewhat unexpected observation that CNR cells, which are more quiescent than CR cells, were more efficiently transduced on d5 and d6 than the latter group of cells. Recent evidence from our laboratory suggests that transduction of CD34+ cells residing in the G0 phase of the cell cycle is possible if G0cells are transduced just prior to cell-cycle activation and proliferation (E.F. Srour, unpublished observations, October 1997). This suggests a possible explanation for the long recognized inefficiency of gene transfer into primitive human HPCs:36,38,39 If the earliest human progenitor cells are in a state of deep dormancy, then transduction of these cells after 24 to 48 hours of cytokine prestimulation may introduce the transduced genetic material into these cells long before they are ready to enter active phases of the cell cycle and begin the process of integration of transduced genes into cellular DNA. In fact, Emmons et al42recently demonstrated the possibility of transducing human CD34+ cells without growth factors, only to recognize poor marking when these cells were transplanted in vivo and monitored for a period of 18 months posttransplant. This, in turn, may explain why transduction of murine stem cells is more efficient than transduction of their human counterparts, since murine stem cells have been recently reported to be continuously cycling.43

Although it has been previously demonstrated that cytokine prestimulation increases transduction efficiency,19,44,45it appears from our studies that the rate of recruitment of primitive HPCs into active phases of the cell cycle and therefore precise timing of transduction is essential for efficient and sustained gene transfer. In a recent study, Boezeman et al46 demonstrated that differences in the rate of hematopoietic colony outgrowth from differentiated (CD34+ CD13+ CD33+) versus more primitive (CD34+ CD13+CD33−) progenitors are based on a delay in growth initiation by cells of the latter group. In these studies,46 the delay in growth initiation was 2.6 to 3.1 days, suggesting that transduction of CNR cells on d5 or d6 may have allowed ample time for initiation of proliferation of primitive HPCs. Based on data presented in this report, it becomes clear that delayed transduction of cultured cells till after d4 may favor efficient gene transfer only because of concomitant cell-cycle activation of primitive HPCs and retroviral infection of these cells. On the other hand, prolonged exposure of CD34+ cells, including CNR cells, to cytokines raises the concern that prestimulation may induce differentiation of stem cells such that the observed level of gene transfer into CNR cells may not reflect efficient gene transfer into stem cells. This is especially true in view of our previously published observations demonstrating that although CNR cells are relatively enriched for primitive HPCs, the hematopoietic potential of these cells is usually compromised relative to freshly isolated CD34+cells.23,25,33 Evidence for the negative effects of exposure of human CD34+ cells to in vitro cytokine stimulation for more than 3 to 4 days can be gleaned from studies in which ex vivo–expanded cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID47 or bnx35 mice to assess the marrow-repopulating potential. Bhatia et al47 reported that although a modest increase in SCID-repopulating cells was possible after 4 days of culture of cord blood hematopoietic cells, all such activity was lost following 9 days of ex vivo expansion. Similarly, CD34+ cells transduced for 3 days in the presence of exogenous cytokines but in the absence of stromal cells failed to successfully engraft bnx mice.48 In a more recent report, the same group of investigators49 questioned whether self-renewing divisions of hematopoietic stem cells can be achieved in vitro and associated the lack of such an event with the low level of gene transfer efficiency into human marrow-repopulating cells. A somewhat unexpected observation was the degree of double labeling of individual progenitors with vector 1 on d1 followed by vector 2 (Fig7). It is conceivable that an actively proliferating cell may divide several times during a 6-day period, allowing for the integration of both neoR genes delivered by each of the two vectors.

In conclusion, we demonstrate in this communication the feasibility of transducing the more primitive HPCs contained within total BM CD34+ cells as assessed by the ability of these cells to sustain long-lived in vitro hematopoiesis and the continued expression of the transduced genetic material. Furthermore, our results indicate that primitive HPCs can be successfully transduced when present among more mature progenitors, thus excluding the need to purify and isolate these cells before transduction. These studies may have important implications in the design of clinical gene therapy protocols.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. RO1 HL55716, Grant No. PO1 CA59348 from the National Cancer Institute, and a research award from the Phi Beta Psi Sorority (E.F.S.). Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research is a Center for Excellence in Molecular Hematology (NIDDK P50 DK49218).

Address reprint requests to Edward F. Srour, PhD, Indiana University School of Medicine, 1044 W Walnut St, R4-202, Indianapolis, IN 46202-5121.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.