Abstract

The expression of many cytokines is dysregulated in individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1). To determine the effects of HIV-1 infection on cytokine expression in individual cells (at the single cell level), we investigated the intracellular levels of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, and IL-8) and hematopoietic growth factors (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF], granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [GM-CSF]) in monocyte-derived macrophages, mock-infected, or infected with HIV-1 by immunocytochemical staining for cytokine protein and compared this with secreted cytokine levels as determined by specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). No difference in the frequency or intensity of cell-associated immunocytochemical cytokine staining could be observed between HIV-1 and mock-infected cells even though the level of secreted proinflammatory cytokines increased and the hematopoietic growth factors decreased in HIV-1–infected cultures. Furthermore, equal expression of cytokine mRNA was observed in all cells in the culture regardless of whether the cells were productively infected with HIV-1 as determined by double-labelling immunocytochemical staining for HIV-1 p24 antigen and in situ hybridization for cytokine mRNA expression. These results indicate that HIV-1 infection results in dysregulation of intracellular cytokine mRNA expression and cytokine secretion not only in HIV-1–infected cells, but also through an indirect way(s) affecting cells not producing virus.

INFECTION BY THE HUMAN immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) initiates a slowly progressing degenerative disease of the immune system, termed the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Beside lymphocytes, cells of the macrophage lineage are major target cells for HIV-1.1-3 HIV-1–infected macrophages persist in tissues for extended periods of time containing latent proviral DNA or large numbers of infectious particles within cytoplasmic vacuoles.4 Furthermore, monocytes/macrophages (MO/MAC) may be important as vehicles for viral dissemination throughout the body. In tissues such as the lung and the brain, HIV-1 is located primarily in macrophage-like cells (ie, alveolar macrophages and microglia, respectively).5,6 Macrophages are also believed to be a vehicle for the transmission of the virus between individuals because for mucosal infection, it was found that a crucial property of the transmitted HIV-1 variant is its tropism for macrophages.7

Macrophages are major effector cells of the immune system and play an essential role as regulator cells in hematopoiesis. Many of the immunoregulatory and effector functions are mediated by cytokines secreted by macrophages under a variety of physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions. Disturbances in the production of cytokines in macrophages and other immune cells by HIV-1 infection may bring about immune dysfunction, which leads to AIDS.4,8,9In addition, abarrant cytokine secretion may lead to a cascade of secondary events that are likely to cause the wasting syndrome, neurologic manifestations of disease, and changes in T-cell responses (ie, switching from a T helper 1 to a T helper type 2 activity).10-12

Cytokines influence the activity of the immune system and their regulation is important in maintaining an effective immune response.13 Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α are cytokines involved in the regulation of inflammation.14,15 IL-8 is an activating factor for neutrophils with chemotactic activity for migrating immune cells.16,17 The hematopoietic growth factors, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), regulate the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells.18,19 In addition to their proliferative role, they contribute to maintaining cell viability and stimulate the functions of mature macrophages and granulocytic cells.20

Dysregulation of cytokine production by macrophages infected with HIV-1 can be demonstrated in vitro. Increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α has been observed in HIV-1–infected macrophages.8,9,21,22 On the other hand, a downregulation of the hematopoietic growth factors M-CSF, G-CSF, and GM-CSF was observed when macrophages were infected with HIV-1.23

The goal of this study was to examine if the dysregulated cytokine secretion of MO/MAC due to HIV-1 infection can be correlated to an altered pattern of cytokine expression in these cultures at the single-cell level. Immunocytochemical staining for cellular cytokine protein expression and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for secreted cytokine measurement was used to examine the pattern of cellular cytokine protein expression in individual cells compared with secreted cytokine levels. Furthermore, a double-labelling method combining immunocytochemistry for HIV-1 p24 antigen detection and in situ hybridization for cytokine mRNA was used to simultaneously examine individual cells for the effects on the expression of cytokine mRNA by HIV-1 replication within these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from healthy donors by density gradient centrifugation and cultured in supplemented RPMI 1640 with 5% heat-inactivated human AB serum on hydrophobic Teflon foils.24 The MO-derived MAC were separated by adherence in plastic chamber slides (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) and cultured in RPMI 1640 with 5% human AB serum. Cells were fixed for immunocytochemistry with 4% paraformaldeyde at the indicated time points. The adherent cell layer (6 to 10 × 105MAC/chamber slide) consisted of up to 95% MAC as judged by morphology, nonspecific esterase staining, and expression of CD14 antigen. Detection of CD14 was performed by immunocytochemistry using the monoclonal antibody (MoAb) My 4 (Coulter, Hamburg, Germany).

HIV-1.

Preparations of HIV-1 stock were obtained by propagating the virus in peripheral blood T cells or MAC cultures, respectively, and harvesting the culture at the peak of infectivity. The cell suspension (106 cells/mL) and cell-free supernatant with a reverse transcriptase activity of 5 × 105 to 1 × 106 cpm/mL/90 minutes was stored in aliquots at −70°C until further use.3 Only mycoplasma-free virus stocks, tested with a mycoplasma tissue culture DNA probe assay (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA), were used. We used the monocytotropic strain HIV-1D117III derived from a perinatally infected child. It rapidly replicates to a high titer in MAC.3,25 As a control, cell suspension and cell-free supernatant were prepared from uninfected cultures corresponding the protocol for stock virus and used for mock infection.23

HIV-1 infection of MAC.

The PBMC were infected with 1 mL stock virus per 10 mL cell suspension in Teflon bags. Cultures were inoculated either with HIV-1–infected T-cell suspension on day 1 (protocol 1) or cell-free supernatant of HIV-1 MAC cultures on day 8 (protocol 2). Control cultures were incubated with corresponding mock material (see above). After 7 days postinfection, MO/MAC were separated by adherence whereby the virus inoculum and the nonadherent cells were removed by washing the cell layer several times with serum-free medium. The infection of the MO/MAC cultures was demonstrated by determination of HIV-1 antigen concentration in the supernatant of the cultures using an HIV-1 antigen ELISA (Organon Teknika, Eppelheim, Germany).

Stimulation of MAC and determination of cytokine secretion.

At the indicated time points, MAC were stimulated for 4 and 24 hours in fresh medium with or without 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharides (LPS,Salmonella abortus equi, kindly provided by C. Galanos, Max Planck Institut, Freiburg, Germany). Cell supernatant was harvested, filtered through 0.22 μm membranes (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany), aliquoted, and stored at −70°C. The supernatants were analyzed using specific ELISAs for the following cytokines: IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, G-CSF, GM-CSF (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); TNF-α (Endogen, Boston, MA). The amount of cytokine measured with ELISA was normalized to the cell number counted in the well at the time when the supernatant was harvested.

Immunostaining for cytokines.

After cultivation, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and stored in 70% ethanol at −20°C until use. The cells were incubated for 30 minutes with 0.1% saponin, which permeabilized the cell membranes for antibody interaction with intracellular antigens. After washing with PBS, the cells were exposed to 10% human serum for 30 minutes followed by incubation with one of the monoclonal antibodies overnight at 4°C: mouse antihuman IL-1β (1:300, FIB-3, Dianova, Hamburg, Germany); mouse antihuman IL-6 (1:10, IL-6–8, Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany); mouse antihuman TNF-α (1:1,000, TNF-E, kindly provided by G.R. Adolf, Bender GmbH, Vienna, Austria), mouse antihuman IL-8 (1:1,000, subclone 4G9/A5/A7, kindly provided by M. Ceska, Sandoz, Vienna, Austria), mouse antihuman G-CSF (1:100, clone 5.24, Oncogene Science, Uniondale, NY), mouse antihuman GM-CSF (1:100, code ZM213, Genzyme, Cambridge, MA). As a negative control (1:20, isotype control) IgG1 was used (Dianova). Afterwards the cells were exposed to peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse immunoglobulins (1:100, Dako, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 minutes, peroxidase-conjugated rabbit antigoat immunoglobulins (1:100, Dako) for 30 minutes, and finally the peroxidase reaction was developed by incubation with diaminobenzidin (DAB-kit Vectastain; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), which resulted in a brown reaction product. For quantitation, positive and negative cells were counted using a 25X objective. A total of 200 cells were counted two times for each slide and the mean was calculated. This evaluation was performed exemplarily by two individuals and no considerable difference was found. The statistical significance was calculated using the χ2 test.

Double-labelling methodology: HIV-1 p24 immunostaining and in situ hybridization for cytokine mRNA detection.

After cultivation, the cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and stored in 70% ethanol at −20°C until use. The peroxidase immunostaining with Vectastain Elite ABC-System (Vector Laboratories) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the fixed cells were rehydrated in PBS for 15 minutes and exposed to normal human serum for 30 minutes, HIV-1 anti-p24 antibody (mouse MoAb Kal-1, 1:100, Laboserv, Eggenstein, Germany) overnight at 4°C and biotinylated antimouse antibody for 30 minutes. Incubation with ABC-Elite reagent containing avidin and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase was performed for 30 minutes at room temperature. Incubation with peroxidase substrate 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) was performed until color developed. The slides were then incubated with 2 × sodium sodium citrate (SSC) at 60°C for 10 minutes to prepare them for in situ hybridization. Prehybridization for 1 hour at 37°C was followed by hybridization overnight at 37°C with 200 ng/mL antisense oligoprobe labeled with digoxigenin (IL-8 BPR 100; IL-6 BPR 32; TNF-α BPR 49, British Biotechnology, Oxon, UK). Washing conditions were: 2 × 10 minutes with 4 × SSC/30% formamide at 37°C, 2 × 10 minutes with 2 × SSC/30% formamide at 37°C and 0.2 × SSC/30% formamide at 37°C, as well as 2 × 10 minutes washing with Tris/HCl/bovine serum albumin (TBS)/0.1% Triton X-100. After the washing steps, 1:600 diluted antidigoxigenin antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) was added for 60 minutes at 37°C. After 2 × 10 minutes washing with TBS, the samples were incubated with revealing buffer (100 mmol/L TrisHCl pH 9.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2; 0.2 mmol/L 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate [BCIP], 0.2 mmol/L nitroblue tetrazolium salt [NBT]) for 3 hours at 37°C.

RESULTS

Immunocytochemical identification and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in uninfected MO/MAC.

Intracellular protein localization and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) were examined in unstimulated and LPS-stimulated MO/MAC cultures on day 8 and day 15 after start of culture. Intracellular cytokines were demonstrated using immunocytochemical techniques and specific MoAbs. In unstimulated MAC, no intracellular IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were detected. In contrast, a constitutive expression of IL-8 protein was demonstrated by a positive staining in about 75% to 90% of the cells (Table 1). After LPS-stimulation IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were produced and the staining for IL-8 became more intense in 41% to 56% of the positive cells (Table 1). A different pattern of staining during stimulation with LPS for the cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α occurred compared with IL-1β. After 4 hours of stimulation with LPS, MAC exhibited a granulated staining in distinct parts of the cytoplasma for IL-8 (Fig 1B), as well as for IL-6 and TNF-α (data not shown). After 24 hours, a diffuse staining of the whole cell was observed, as shown for IL-8 in Fig 1C. IL-1β producing MAC on the other hand, exhibited diffuse cytoplasmic staining both after 4 hours and 24 hours (Fig 1D and E). Positively stained cells were counted and the results are summarized in Table 1. IL-1β was detectable after 4 hours of stimulation in the majority of the cells (64% to 85%). After 24 hours, a more intense staining for IL-1β was observed in 5% to 10% of these cells. TNF-α production was detectable after stimulation with LPS for 4 hours in 7% to 14% of the cells clearly identified by the characteristic granulated staining. After 24 hours, the percentage of TNF-α–synthesizing cells increased to 43% to 61% with a diffuse staining. A total of 10% to 15% of the cells produced IL-6 after 4 hours of stimulation and 50% to 80% after 24 hours. Staining with IL-8 antibody resulted in 54% to 96% positive cells in unstimulated and LPS-stimulated cultures. The response of the cells to LPS was reflected in the additional occurrence of characteristic granular staining after 4 hours of stimulation and subsequently in a strong diffuse staining after 24 hours. The secretion of cytokines in the corresponding supernatant was assayed with the ELISA technique to compare with the immunocytochemical expression of cell-associated cytokines. Without stimulation, MAC did not release IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, whereas for IL-8, a constitutive secretion was observed (Table 2). The amount of IL-8 that was secreted, however, was strongly enhanced by stimulation with LPS. Corresponding to the enhancement in the percentage or intensity of cellular staining after 24 hours of stimulation, the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 increased further between 4 hours and 24 hours, whereas TNF was maximally secreted after 4 hours of stimulation.

Immunocytochemical staining of uninfected MAC. By using IgG1 antibodies for negative control (isotype control), only an unspecific staining of the area of the nucleus of the cells was seen (A). With specific anti–IL-8 antibodies, intracellular IL-8 could be detected after 4 hours stimulation with LPS as granulated staining (B) and after 24 hours LPS as diffuse staining (C). After 4 hours stimulation with LPS, low amounts of IL-1β could be detected (D) and after 24 hours LPS, a strong specific staining was observed (E). Intracellular G-CSF could be detected in unstimulated cultures (F), as well as in LPS-stimulated cultures (G) (× 1,500).

Immunocytochemical staining of uninfected MAC. By using IgG1 antibodies for negative control (isotype control), only an unspecific staining of the area of the nucleus of the cells was seen (A). With specific anti–IL-8 antibodies, intracellular IL-8 could be detected after 4 hours stimulation with LPS as granulated staining (B) and after 24 hours LPS as diffuse staining (C). After 4 hours stimulation with LPS, low amounts of IL-1β could be detected (D) and after 24 hours LPS, a strong specific staining was observed (E). Intracellular G-CSF could be detected in unstimulated cultures (F), as well as in LPS-stimulated cultures (G) (× 1,500).

Immunocytochemical identification and secretion of hematopoietic growth factors in MO/MAC.

Cell-associated cytokines and secretion of the hematopoietic growth factors G-CSF and GM-CSF was examined in unstimulated and LPS-stimulated MO/MAC cultures. Intracellular G-CSF could be detected in 68% to 98% of the cells in unstimulated and LPS-stimulated MAC cultures (Table 1, Fig 1F and G). The percentage of GM-CSF–producing cells in unstimulated as well as LPS-stimulated cultures was 82% to 99% (Table 1). Secretion of both G-CSF and GM-CSF was not detected in the supernatant of unstimulated MO/MAC cultures until the cultures were stimulated with LPS (Table 2).

Immunocytochemical identification and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and hematopoietic growth factors after infection with HIV-1.

It has been reported that the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and hematopoietic growth factors are differentially regulated after infection with HIV-1: an increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and a decreased secretion of hematopoietic growth factors has been shown in HIV-1–infected cultures compared with uninfected cultures from the same blood donor.8,9 21-23 To further examine this differential regulation at the single cell level by immunocytochemical staining, we analzyed the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and hematopoietic growth factors in individual cells after infection of the culture with HIV-1. The frequency of cytokine positive cells and the intensity of staining for both the proinflammatory cytokines as well as the hematopoietic growth factors, was identical in HIV-1–infected and uninfected cultures (Table 1). However, the levels of the secreted proinflammatory cytokines and hematopoietic growth factors measured in the corresponding supernatants of these cultures showed a twofold to fivefold higher level of proinflammatory cytokines in the infected cultures compared with the uninfected control cultures (Table 2), whereas G-CSF and GM-CSF secretion was reduced on infection by a factor of 2 to 6 (Table 2). To exclude that these effects may be due to cytokines in virus inoculum, we measured cytokine levels (ie, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, G-CSF, GM-CSF, and M-CSF) in the virus and the mock inoculum. We found nearly identical cytokine amounts in the virus inoculum and the mock inoculum (data not shown).

Detection of HIV-1 p24-positive cells and cytokine mRNA expressing cells by combined immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization.

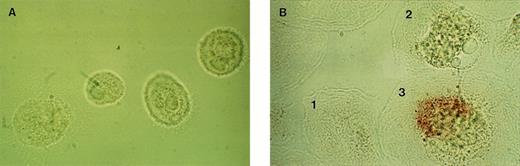

To determine whether HIV-1–infected cells, in particular, were responsible for the increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines or whether an indirect effect was responsible for the changes in cytokine secretion, a double-labelling methodology was used to examine both the cytokine mRNA expression and HIV-1 infection in the same cell. Cell-associated cytokine mRNA for IL-8, IL-6, and TNF-α was detected by in situ hybridization and HIV-1 p24 antigen by immunocytochemistry. After stimulation with LPS for 24 hours, the same percentage of cytokine mRNA positive cells was found in HIV-1–infected and uninfected cultures: 78% to 86% MAC were IL-8 mRNA positive, 58% to 68% were IL-6 mRNA positive, and 41% to 50% were TNF-α mRNA positive (Table3). Figure 2B shows the three possible outcomes of immunocytochemical staining for HIV-1 p24 antigen and in situ hybridization for cytokine mRNA expression. Cell no. 1 is both p24-negative and IL-8 mRNA negative, cell no. 2 exhibits a positive signal for IL-8 mRNA, but no p24 antigen expression, and cell no. 3 exhibits both IL-8 mRNA and p24 expression. In the HIV-1–infected cultures, the percentage of cytokine-mRNA positive cells was similar either in the proportion of the p24-positive, as well as p24-negative MAC (Table 3).

Detection of HIV-1 p24-positive cells and cytokine mRNA expressing cells by combined immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. (A) Negative control (LPS-stimulated, uninfected MAC hybridized with IL-8 sense oligonucleotides). (B) Simultaneous detection of HIV-1 p24 (red staining) with immunocytochemistry and IL-8 mRNA in LPS-stimulated MAC with in situ hybridization (dark granules) at day 22 after start of culture. Cell no. 1, HIV p24-negative and IL-8–negative; cell no. 2, HIV p24-negative and IL-8–positive; cell no. 3, HIV p24-positive and IL-8–positive (×1,500).

Detection of HIV-1 p24-positive cells and cytokine mRNA expressing cells by combined immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization. (A) Negative control (LPS-stimulated, uninfected MAC hybridized with IL-8 sense oligonucleotides). (B) Simultaneous detection of HIV-1 p24 (red staining) with immunocytochemistry and IL-8 mRNA in LPS-stimulated MAC with in situ hybridization (dark granules) at day 22 after start of culture. Cell no. 1, HIV p24-negative and IL-8–negative; cell no. 2, HIV p24-negative and IL-8–positive; cell no. 3, HIV p24-positive and IL-8–positive (×1,500).

DISCUSSION

Despite the existence of conflicting data, most results show a dysregulated cytokine production in HIV-1 infection. Elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α have been found in the sera of HIV-1–infected individuals.26-29In addition, cells from HIV-1–infected patients cultured in vitro,26,30,31-38 as well as in vitro infected MO/MAC,39-42 release high levels of these cytokines. The information about the regulation of hematopoietic growth factors is more limited. Some investigators have shown lower levels in HIV-1–infected patients for GM-CSF,43,44 whereas others,45 have found normal or even higher levels. The dysregulated expression of cytokines during infection with HIV-1 may contribute to the pathogenesis of AIDS.10-12 To determine the effects of HIV infection on the regulation of specific cytokines by MO/MAC, we analyzed the secretion by MO/MAC of these cytokines in the supernatant by ELISA and the expression of these cytokines at the single cell level using an indirect immunoperoxidase staining method and in situ hybridization.

In the absence of LPS, no secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α was detected in either infected or uninfected MAC and intracellular staining for these proteins could not be detected by immunostaining. Similar results have been found by Molina et al46 for the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α and by Gan et al47for IL-6. In contrast, other investigators found an induction of IL-6 when these cells are infected by HIV-1.30,41 This contradiction may be due to contaminating endotoxins present in certain sera used in culture media. Endotoxins are known to be activators of MO/MACs.48 IL-8, on the other hand, was produced constitutively in uninfected cells and secretion was elevated by HIV-1 infection. Constitutive expression of IL-8 in uninfected MO/MAC has been reported by others.49 Secreted IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were detected after MO/MAC were stimulated by LPS and levels were significantly higher in HIV-1–infected cultures compared with uninfected cultures, whereas secreted levels of G- and GM-CSF decreased in HIV-1–infected cultures. Molina et al50reported similar results for THP-1 cell line that acutely infected cells compared with chronically or uninfected cells expressed significantly higher levels of LPS-induced IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α on protein and at the mRNA level. These results indicate that HIV-1 potentiates the inflammatory response of MO/MAC and suppress hematopoietic activities.

LPS stimulation of uninfected MO/MAC resulted in the induction of intracellular IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α and IL-8 staining became more intense (Fig 1 and Table 1). A characteristic, granulated staining in juxtanuclear position for TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 early after LPS stimulation was observed. Others51,52 observed a similar staining pattern for IL-6 and TNF-α and attributed this to a localization of these proteins in the Golgi zone. After 24 hours of stimulation, these proteins were distributed evenly within the cell, probably due to the intracellular transport to the cell membrane. No granulated staining was found for IL-1β (Fig 1D), again confirming results by others who could not localize IL-1β in the endoplasmic reticulum.53,54 Unlike most secreted proteins, IL-1β has no signal sequence and is secreted via a pathway different from the classical endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi route. Rubartelli et al55 suggested that IL-1β is contained partly within intracellular vesicles, which protect it from protease digestion. In contrast to the proinflammatory cytokines, which were induced by LPS, the staining for hematopoietic growth factors, G- and GM-CSF, was similar in unstimulated and LPS-stimulated cultures (shown for G-CSF in Fig 1F and G and Table 1). Furthermore, levels of secreted G- and GM-CSF appeared in the supernatant after stimulation with LPS. This may be due to an induction of secretion by LPS (Table 2).

The analysis of cytokine protein and mRNA expression at the single cell level in the MO/MAC cultures showed that even though the secreted cytokine levels were several-fold higher in the supernatant, there were no significant changes in the levels of mRNA and protein expression within the infected cells. Others have shown that intracellular expression of IL-1β and TNF-α in MO/MACs recovered from HIV-1–infected and uninfected individuals were not significantly different.56 Thus, an altered level of cytokine secretion without a simultaneous change in the intracellular cytokine level implies that other mechanisms such as the cytokine turnover in individual cells and/or posttranslational processing must be taking place. Posttranslational mechanisms have been reported for TNF-α and IL-1β.57,58 For TNF-α, it has been shown that IL-1–stimulated production in the cytotrophoblastic cell line BeWo is independent from TNF-α mRNA induction and de novo protein synthesis.57 IL-1β release from human monocytes is promoted by adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent intracellular ionic changes.58

By using double-labelling immunocytochemistry to stain intracellular HIV-1 p24 and in situ hybridization to identify cytokine mRNA, we showed that p24-positive MAC express similar amounts of proinflammatory cytokine mRNA when compared with p24-negative MAC (Fig 2B, Table 3). Our data indicate that HIV-1 infection most likely acts in an indirect way leading to an altered cytokine production in the entire MAC culture. The question is how HIV is altering the cytokine production not only in the HIV-1–infected cells, but in the whole culture? One possible explanation would be the paracrine action of HIV-1 transactivating protein Tat, which is released by infected cells and taken up by uninfected cells.59,60 Tat can induce TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, and interferon (IFN)-γ in a dose-dependent manner.61,62 This effect is not only due to transcriptional, but also translational control. Experiments by Braddock et al63 showed that Tat increased the efficiency of translation. This was originally confirmed by the observation that the increase in protein synthesis exceeds the increase of mRNA. An enhanced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines may be due to an accelerated transport from the inside of the cells to the outside. In addition, it has been shown that Tat can bind to and inhibit the dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26),64 an enzyme that is expressed on monocytic cells.65 This enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of cytokines with specific N-terminal peptide sequences, like TNF-α or IL-6.66 Thus, Tat could increase the level of cytokines in the supernatant by inhibiting the peptidase activity and thereby inhibiting cytokine degradation. For TNF-α, it has been shown that dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity regulates the extracellular TNF-α concentration.67 68

Here, we have shown that individually HIV-1–infected cells are not directly responsible for the altered levels of secreted cytokine levels, but may exert their action in an indirect manner. This could explain how a low number HIV-1–infected cells (eg, in brain tissue) contribute to HIV-1–related neurologic disorders or immune dysfunction, respectively, by disturbing the cytokine balance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge Silke Deckert for excellent technical assistance; C. Galanos, Freiburg, Germany, for LPS; and M. Ceska, Vienna, Austria and G.R. Adolf, Vienna, Austria, for providing antibodies. For statistical analysis, we thank U. Alex.

Supported by a grant from the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft, Forschung und Technologie (DLR: III-004-89/FVP4 and 01KI9411). The Georg-Speyer-Haus is supported by the Bundesministerium für Gesundheit and the Hessische Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst.

Address reprint requests to Reinhard Andreesen, MD, Department of Hematology and Oncology, University of Regensburg, Franz-Josef-Strauss-Allee 11, D-93055 Regensburg, Germany.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.