Abstract

Expression of the NF-κB–dependent gene A20 in endothelial cells (EC) inhibits tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–mediated apoptosis in the presence of cycloheximide and acts upstream of IκBα degradation to block activation of NF-κB. Although inhibition of NF-κB by IκBα renders cells susceptible to TNF-induced apoptosis, we show that when A20 and IκBα are coexpressed, the effect of A20 predominates in that EC are rescued from TNF-mediated apoptosis. These findings place A20 in the category of “protective” genes that are induced in response to inflammatory stimuli to protect EC from unfettered activation and from undergoing apoptosis even when NF-κB is blocked. From a therapeutic perspective, genetic engineering of EC to express an NF-κB inhibitor such as A20 offers the mean of achieving an anti-inflammatory effect without sensitizing the cells to TNF-mediated apoptosis.

ENDOTHELIAL CELLS (EC), which are frequently exposed to the pleiotropic cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF) at sites of inflammation, are usually resistant to TNF-mediated apoptosis. This resistance is mediated by de novo expression of a set of “protective genes.” Recent reports pointed to the critical role of the transcription factor NF-κB in the induction of those protective genes.1-3 As recently shown by several groups, blockade of NF-κB activation by overexpression of its inhibitor IκBα or by knocking out the p65/RelA sensitizes embryonic fibroblasts, macrophages, jurkat cells, and a fibrosarcoma cell line to TNF-induced apoptosis.1-3 We have previously reported a similar finding in primary EC (C.J. Wrighton et al, personal communication, September 1995).

We recently showed that the expression of A20, a zinc finger protein originally identified as a TNF-inducible gene in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC)4 and shown to be dependent on NF-κB for its expression,5,6 inhibits activation of NF-κB in EC.7 Our studies showed that the expression of A20 in EC suppressed the activation of a reporter that is dependent solely on NF-κB as well as reporters for several of the NF-κB–dependent genes, including E-selectin, interleukin (IL)-8, IκBα, and tissue factor, that are upregulated when EC are activated.8-12

In the present studies, we transduced primary EC with a recombinant A20 adenovirus (rAd.A20), which leads to high levels of A20 protein expression in almost 100% of cells. This allowed us (1) to confirm that expression of A20 would inhibit upregulation of NF-κB–dependent genes in their normal DNA context, (2) to dissect the level at which NF-κB inhibition occurs, and (3) to evaluate whether inhibition of NF-κB in EC by A20 would sensitize the cells to TNF-mediated apoptosis, as with IκBα, or whether the antiapoptotic function of A20 would prevent such sensitization. Although A20 was described based on its antiapoptotic function in B cells and fibroblasts,13 14 this property has not been tested in EC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer to porcine aortic endothelial cells.

Fresh EC were isolated from porcine aortas15 by scraping and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS; High Clone, GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY) and 50 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Ninety percent to 100% of confluent porcine aortic endothelial cells (PAEC) monolayers from the fifth or the sixth passage were infected with the rAd.A20, the rAd.IκBα, or the control rAd.β-gal at a moiety of infection (MOI) of 500 in 1% FCS DMEM supplemented with penicillin (125 U/mL), streptomycin (125 mg/mL), and L-glutamine (2 mmol/L; all purchased from GIBCO-BRL) and incubated for 1.5 hours in a 5% CO2 humid incubator on a rocking platform. Following the initial 1.5 hours, FCS-enriched medium was added to the rAd-infected cells to achieve a 10% FCS final concentration. Twenty-four hours following the infection, the medium was changed and the cells allowed to rest for an additional 24 hours before being assessed for the expression and the function of the transferred gene. Infection of PAEC with 2 rAd. (rAd.IκBα and rAd.β-gal or rAd.A20) was achieved at a combined MOI of 1,000. Expression of the transgenes was evaluated by immunohistochemistry labeling using a mouse anti-human A20 monoclonal antibody (MoAb) (kind gift of Dr Vishva Dixit, University of Michigan, Ann Harbor), a rabbit anti-IκBα polyclonal (MAD-3) anti-serum (Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) that cross-reacts with the porcine IκBα protein,16 or Northern blot analysis using specific radiolabeled cDNA probes.

Recombinant adenoviruses.

The rAd.A20 is a kind gift of Dr. Vishva Dixit; the rAd.β-gal, used as a control adenovirus, is a kind gift of Dr Robert Gerard (University of Texas SW); and the rAd.IκBα was generated by C.J. Wrighton as described and expresses the porcine IκBα gene (ECI-6).16 In brief, construction of these rAd. was done by cloning the respective gene's cDNA in the pAC.CMV-pLpASR+ vector as described.17 This A20 pAC plasmid was then cotransfected with pJM17, a recombination plasmid system developed by McGrory et al18 in the 293 embryonic kidney cell line. To reduce the possibility of wild-type virus being produced from a plasmid that contains adenovirus genomic DNA, the pJM17 vector had a plasmid vector sequence inserted in the E1 region, which makes the DNA molecule too large to package in an adenovirus particle.19 Production of rAd. was done in the embryonic kidney 293 cell line. Recombinant adenoviruses were subsequently purified by two consecutive cesium chloride centrifugations and tittered by limiting dilution on 293 cells.

Reagents.

PAEC were stimulated with either 100 ng/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS;Escherichia coli 0B55; Sigma, St Louis, MO), 100 U/mL of recombinant human TNF (kind gift of Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, NJ), 5 × 10−8 mol/L of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), 300 μmol/L of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), or 10 U/mL of human α-thrombin (Sigma). In some experiments the inhibitor of serine proteases, dichloroisocoumarin (Sigma), was added 30 minutes before the given agonist at the concentration of 25 μmol/L. The inhibitor of translation cycloheximide (CHX) used at a final concentration of 2 μg/mL and the propidium iodide (PI) used in apoptosis assays were purchased from Sigma.

Nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Nuclear proteins were extracted from PAEC before stimulation and 2 hours after stimulation with TNF according to the method described elsewhere.20 Protease inhibitors were added in all buffers used during nuclear extraction, namely phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF); 50 μg/mL), leupeptin (0.5 μg/mL), antipain (0.5 μg/mL), aprotinin (0.5 μg/mL), pepstatin (1 μg/mL), benzamidine (100 μg/mL), chymostatin (100 μg/mL), TLCK (50 μmol/L), and TPCK (100 μmol/L). Protein concentration of nuclear extracts was determined by the Bradford assay.21 Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard. Nuclear extracts were frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until assessed in EMSA. The probes used in EMSA were labeled by random priming with α-[32P]–dATP (80 μCi at 3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) using the Klenow fragment of E coli DNA polymerase I in the presence of nonlabeled dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP. Binding reactions in 25 μL contained 100,000 cpm of double-stranded oligonucleotide; 3 μg of poly (dI-dC); and 5 μg of nuclear extract proteins in 20 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.9, 50 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, and 5% glycerol; they were performed for 30 minutes at room temperature (RT). For electrophoresis, high ionic strength 6%-polyacrylamide gels were used as described.22 A double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the second porcine ECI-6 (IκBα) oligonucleotide (BS-2-5′-AATTCGGCTTGGAAATTCCCCGAGCG-3′) was used for NF-κB EMSA.23

Cytoplasmic extracts and Western blot analysis of IκBα expression.

Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared before, 10 minutes after, and 2 hours after TNF (T) treatment from noninfected (NI), rAd.A20, or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC, as described.16 Protein concentration of these cytoplasmic extracts was quantitated by the Bradford method. Twenty micrograms of protein per sample was evaluated by Western blot analysis for IκBα expression, as described.16 IκBα was detected using anti–MAD-3 rabbit polyclonal IgG antiserum (#C-21) from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology and a peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL) followed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection (Amersham).

RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis.

RNA was extracted from PAEC expressing or not the different transgenes before and 2 hours following stimulation by the different agonists. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (GIBCO-BRL) according to the method described by Chomczynski and Sacchi.24 The amount of extracted RNA was calculated from optical density (OD) measurements at 260 nm (1 OD260 ∼ 40 μg/mL). Purity and integrity of RNA samples were confirmed in 1% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. For Northern blot analysis, equal amounts of RNA (10 μg per lane) were loaded and run on a 1.3% agarose/formaldehyde gel. RNA was then transferred to a nylon membrane and hybridized to cDNA probes encoding for porcine E-selectin25; porcine IL-8 derived by E. Hofer (unpublished observation, September 1993); porcine IκBα (ECI-6)23; human vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 that was shown to cross-hybridize with its porcine homologue, a kind gift of Dr T. Collins (Children's Hospital, Boston MA); junB, a kind gift of Dr Ulrich Rulter (Heidelberg, Germany); and an A20 cDNA probe corresponding to a 250-bp HindIII-released fragment from the N-terminus of the sequence.4 In all experiments, a cDNA probe for human glyceraldehyde triphosphate dihydrogenase (GAPDH) was used to confirm equal loading of RNA in all the wells. All probes were labeled with α-[32P]–dATP (Amersham) using a random primer labeling kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

E-selectin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Noninfected or rAd.-infected PAEC were grown to confluence in 96-well microtiter plates. These cells were then stimulated with the different stimuli prementioned. Four hours following stimulation, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in ice-cold 0.02% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 5 minutes. Cells were then incubated with a mouse MoAb (BBA1) directed against human E-selectin26 and shown to cross-react with porcine E-selectin. The BBA1 MoAb was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and used at a 1:10,000 dilution of the hybridoma supernatant. A goat anti-mouse peroxidase–coupled polyclonal antibody purchased from Pierce was used as secondary antibody. Optical density was determined at 490 nm on an LKB ELISA reader.

Cell viability assay.

Cell viability was assessed by means of the vital dye crystal violet uptake. In brief, cells are stained for 5 minutes with crystal violet solution then washed thoroughly under tap water. Colored cell monolayers are then dried and the crystals subsequently dissolved in 10% acetic acid before read on an LKB ELISA reader at 405 nm wavelength. OD values of NI, nontreated cells were considered to reflect 100% cell viability.

Apoptosis assay.

Cell death by apoptosis was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of DNA content. Briefly, following treatment PAEC were obtained, washed twice with PBS, resuspended in ice-cold 70% ethanol with gentle vortexing to a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL, and stored at 4°C until analysis. Before quantification of DNA content, PAEC were pelleted at 400g for 5 minutes, resuspended into PBS, pelleted again, and resuspended into 200 μL PBS, 0.1% Triton X, 0.1 mmol/L EDTA, 50 μg/mL DNAse free RNAse (Stratagene) with 5 μg/mL PI. DNA content analysis was conducted using a FACScan bench top model (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) with Cellquest acquisition and analysis software (Becton Dickinson). Cellular debris and doublets were excluded from analysis by their forward-light-scatter and right-angle-light-scatter properties.

RESULTS

Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of A20 achieves 100% expression in primary EC cultures.

Primary PAEC were infected with the rAd.A20 at an MOI of 500/cell, previously shown to be optimal for achieving high levels of expression in PAEC without causing significant cytotoxicity.16Immunohistochemical staining of EC transduced with the rAd.A20 using a mouse anti-human A20 MoAb shows high level of A20 expression in almost all PAEC 24 to 48 hours following infection (Fig1). As shown by the labeling, the expression of A20 is mainly cytoplasmic, which is comparable to its endogenous expression.14 The anti-A20 MoAb used does not cross-react with the porcine A20.

Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of A20 achieves high levels of expression in cultured PAEC. Cultured 90% to 100% confluent PAEC, from the fifth or the sixth passage, were either not infected (untreated) or infected with either the control rAd.β-gal (adeno-beta-gal) or rAd.A20 (adeno A20). Forty-eight hours following transduction, PAEC were recovered and cytospinned on glass slides using a cytospin 3 apparatus (Shandon Inc, Pittsburgh, PA) before being assessed by immunohistochemistry for the expression of the A20 transgene. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using a mouse anti-human A20 MoAb of the IgG1 isotype, followed by a secondary peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA; right panel). A nonrelevant mouse MoAb was used as a control (left panel). Results show low to undetectable levels of A20 in noninfected or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC. In contrast PAEC transduced with the rAd.A20 showed high levels of expression of A20 in >95% of the cells. Expression of the A20 protein was limited to the cytoplasm.

Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of A20 achieves high levels of expression in cultured PAEC. Cultured 90% to 100% confluent PAEC, from the fifth or the sixth passage, were either not infected (untreated) or infected with either the control rAd.β-gal (adeno-beta-gal) or rAd.A20 (adeno A20). Forty-eight hours following transduction, PAEC were recovered and cytospinned on glass slides using a cytospin 3 apparatus (Shandon Inc, Pittsburgh, PA) before being assessed by immunohistochemistry for the expression of the A20 transgene. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using a mouse anti-human A20 MoAb of the IgG1 isotype, followed by a secondary peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA; right panel). A nonrelevant mouse MoAb was used as a control (left panel). Results show low to undetectable levels of A20 in noninfected or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC. In contrast PAEC transduced with the rAd.A20 showed high levels of expression of A20 in >95% of the cells. Expression of the A20 protein was limited to the cytoplasm.

A20 expression inhibits NF-κB activation upstream of IκBα degradation.

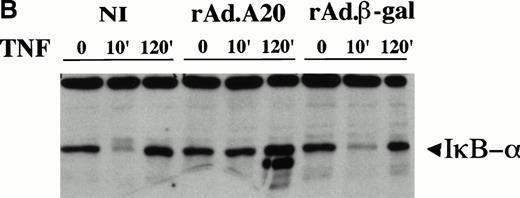

Our previous reporter studies showed that expression of A20 inhibited activation of NF-κB. To determine the level at which inhibition takes place, nuclear as well as cytoplasmic extracts were recovered before, 10 minutes after, and 2 hours after TNF treatment. These extracts were evaluated by EMSA for NF-κB binding and by Western blot analysis for IκBα expression. The data show that overexpression of A20 in EC inhibits translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus following TNF treatment by stabilizing IκBα, ie, inhibition is at a level upstream of IκBα degradation (Fig 2A and B). EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts from PAEC expressing A20 showed almost no inducible binding for NF-κB consensus DNA sequences as opposed to the high binding detected in noninfected or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC 2 hours following TNF stimulation. The moderate binding activity for NF-κB in the A20-expressing cells reflects the presence of a small number of nontransduced PAEC contaminating the cells expressing A20. Specificity of DNA binding in both the noninfected and the A20-expressing PAEC was tested by the use of excess cold wild-type (wt) or mutant (mutκB) κB probes (Fig 2A). Furthermore, we show that A20 expression in PAEC inhibits the usual IκBα degradation that occurs 10 minutes following TNF stimulation (Fig 2B), pointing to the fact that A20 expression inhibits NF-κB activation by stabilizing IκBα expression. A second faster-migrating band is reproducibly detected at 2 hours in the A20-expressing EC. This second band most probably relates to a degradation product of IκBα and disappears if PAEC are pretreated (30 minutes) with low levels (25 μmol/L) of the protease inhibitor dichloroisocoumarin that is not sufficient on its own to inhibit IκBα degradation following TNF treatment (data not shown).

(A) Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear DNA-binding activity following TNF stimulation in rAd.A20–infected PAEC. Nuclear extracts were prepared from noninfected (NI), rAd.A20-infected, or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC before and 2 hours following treatment with TNF(T) (100 U/mL) as described in Materials and Methods. NF-κB activation and binding to a specific κB binding oligo derived from the porcine IκBα promoter was evaluated by means of EMSA as described. Results reveal that nuclear extracts from PAEC expressing A20 had almost no inducible binding activity for NF-κB binding sites. Specificity of DNA binding was tested by the use of excess cold wild-type as a specific competitor (wt) or a mutant κB probe (mutκB) used as a nonspecific competitor. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of IκBα expression following TNF treatment. Cytoplasmic extracts from NI, rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC were recovered before and 10 minutes and 2 hours following TNF treatment and assessed for IκBα expression by means of Western blot analysis. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC inhibits the usual IκBα degradation that occurs 10 minutes following TNF stimulation. A second faster-migrating band is detected at 2 hours in the A20-expressing EC. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

(A) Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear DNA-binding activity following TNF stimulation in rAd.A20–infected PAEC. Nuclear extracts were prepared from noninfected (NI), rAd.A20-infected, or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC before and 2 hours following treatment with TNF(T) (100 U/mL) as described in Materials and Methods. NF-κB activation and binding to a specific κB binding oligo derived from the porcine IκBα promoter was evaluated by means of EMSA as described. Results reveal that nuclear extracts from PAEC expressing A20 had almost no inducible binding activity for NF-κB binding sites. Specificity of DNA binding was tested by the use of excess cold wild-type as a specific competitor (wt) or a mutant κB probe (mutκB) used as a nonspecific competitor. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of IκBα expression following TNF treatment. Cytoplasmic extracts from NI, rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC were recovered before and 10 minutes and 2 hours following TNF treatment and assessed for IκBα expression by means of Western blot analysis. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC inhibits the usual IκBα degradation that occurs 10 minutes following TNF stimulation. A second faster-migrating band is detected at 2 hours in the A20-expressing EC. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

A20 expression in EC inhibits the upregulation of NF-κB–dependent genes in an agonist-independent manner.

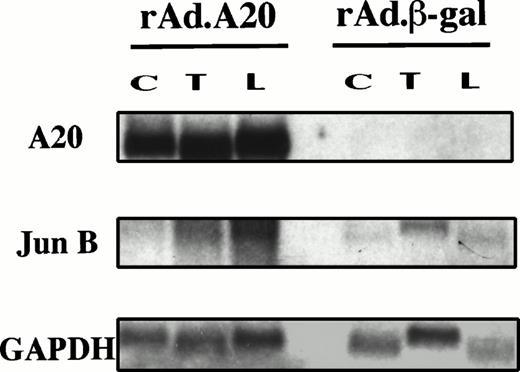

The inhibition of NF-κB is reflected by the decreased induction of several NF-κB–dependent genes in the presence of A20. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC (confirmed by Northern analysis for A20 mRNA) significantly inhibits E-selectin, VCAM-1, and IκBα gene induction (>80% to 90%) following stimulation by TNF, LPS, and PMA as compared with high levels of induction in either NI cells or rAd.β-gal–infected cells. A20 expression also achieved significant inhibition (>70%) of IL-8 gene induction. This effect of A20 is agonist independent; inhibition was seen when EC were stimulated with TNF, LPS, or PMA (Fig 3A). This inhibitory effect on NF-κB–dependent genes was confirmed at the protein level for E-selectin and extended to two other stimuli including human α-thrombin (Th) and H2O2 (H) (Fig 3B). These findings do not support the suggestion that the inhibitory effect of A20 is limited to TNF and IL-1β signaling.27 The induction of a non–NF-κB–dependent proto-oncogene junB28-30 was not decreased by A20 expression as measured at the mRNA level (Fig 4). The proto-oncogene junB remained inducible in rAd.A20-infected PAEC following TNF and LPS stimulation. The level of induction was even greater than that seen in the rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC, although this difference was not significant when corrected with the expression of the house keeping gene GAPDH.

(A) Northern blot analysis of E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, and IκBα gene induction. PAEC were noninfected (NI), rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected at a MOI of 500 as in Fig 1. Forty-eight hours following infection, PAEC were either left nontreated (C) or were stimulated with TNF (T) (100 U/mL), LPS (L) (100 ng/mL), or PMA (P) (5.10−8 mmol/L). A20, E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, IκBα, and GAPDH steady-state transcript levels were quantitated in these samples by Northern blot analysis using α-[32P]–dATP–labeled homologous or cross-reactive cDNA probes as described in Materials and Methods. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC (confirmed by Northern analysis for A20 mRNA) significantly inhibits E-selectin, VCAM-1, and IκBα gene induction (>80% to 90%) following stimulation by TNF, LPS, and PMA as compared with high level of induction in either NI cells or rAd.β-gal–infected cells. A20 expression also achieved significant inhibition (>70%) of IL-8 gene induction. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Inhibition of cell-surface expression of the EC-specific adhesion molecule E-selectin. Confluent PAEC in 96-well microtiter plates were infected as in (A). Triplicate wells of PAEC were either untreated (C) or treated with the same stimuli as in (A) extended to α-thrombin (Th) and H2O2 (H) (300 μmol/L). Expression of the E-selectin protein was analyzed by ELISA 4 hours following stimulation. Results confirm and extend to α-thrombin and oxidative stimuli, the previous mRNA results, by showing that A20 abrogates surface-expression of E-selectin in PAEC for all stimuli tested. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

(A) Northern blot analysis of E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, and IκBα gene induction. PAEC were noninfected (NI), rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected at a MOI of 500 as in Fig 1. Forty-eight hours following infection, PAEC were either left nontreated (C) or were stimulated with TNF (T) (100 U/mL), LPS (L) (100 ng/mL), or PMA (P) (5.10−8 mmol/L). A20, E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, IκBα, and GAPDH steady-state transcript levels were quantitated in these samples by Northern blot analysis using α-[32P]–dATP–labeled homologous or cross-reactive cDNA probes as described in Materials and Methods. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC (confirmed by Northern analysis for A20 mRNA) significantly inhibits E-selectin, VCAM-1, and IκBα gene induction (>80% to 90%) following stimulation by TNF, LPS, and PMA as compared with high level of induction in either NI cells or rAd.β-gal–infected cells. A20 expression also achieved significant inhibition (>70%) of IL-8 gene induction. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Inhibition of cell-surface expression of the EC-specific adhesion molecule E-selectin. Confluent PAEC in 96-well microtiter plates were infected as in (A). Triplicate wells of PAEC were either untreated (C) or treated with the same stimuli as in (A) extended to α-thrombin (Th) and H2O2 (H) (300 μmol/L). Expression of the E-selectin protein was analyzed by ELISA 4 hours following stimulation. Results confirm and extend to α-thrombin and oxidative stimuli, the previous mRNA results, by showing that A20 abrogates surface-expression of E-selectin in PAEC for all stimuli tested. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Induction of the non–NF-κB–dependent gene junB is not inhibited by expression of A20. PAEC were infected and stimulated as in (A) with TNF (T) and LPS (L), and RNA was extracted. Steady-state mRNA levels of A20, junB, and GAPDH were evaluated by Northern blot analysis as described in (A) using a junB cDNA probe shown to cross-react with its porcine homologue. Results show that the proto-oncogene junB is inducible in rAd.A20-infected PAEC, following TNF and LPS stimulation. The level of induction was even greater than that seen in the rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC, although this difference was not significant when corrected for GAPDH.

Induction of the non–NF-κB–dependent gene junB is not inhibited by expression of A20. PAEC were infected and stimulated as in (A) with TNF (T) and LPS (L), and RNA was extracted. Steady-state mRNA levels of A20, junB, and GAPDH were evaluated by Northern blot analysis as described in (A) using a junB cDNA probe shown to cross-react with its porcine homologue. Results show that the proto-oncogene junB is inducible in rAd.A20-infected PAEC, following TNF and LPS stimulation. The level of induction was even greater than that seen in the rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC, although this difference was not significant when corrected for GAPDH.

A20 expression rescues cycloheximide-sensitized EC from TNF-mediated apoptosis.

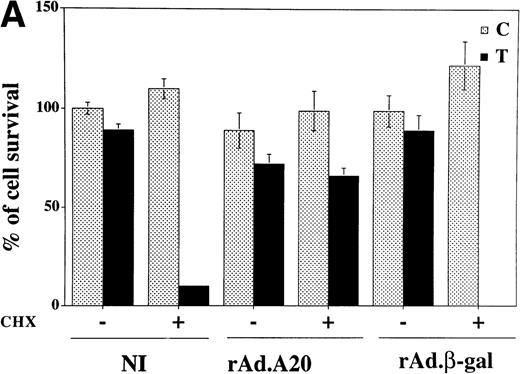

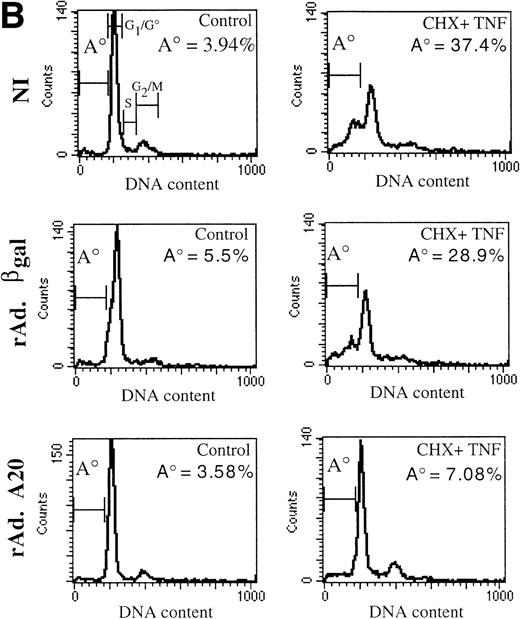

In addition to the suppressive effects just discussed, expression of A20 in PAEC protected those cells against TNF-mediated cell death in the presence of an inhibitor of protein translation, ie, CHX. In the absence of A20, TNF induces apoptosis in CHX presensitized PAEC. Using crystal violet uptake as an indicator of cell viability, no viable cells were seen in NI or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC 7 hours after treatment with CHX/TNF as opposed to more than 60% to 70% viable cells in rAd.A20-infected PAEC treated or not with CHX (2 μg/mL) 30 minutes before the addition of TNF (100 U/mL; Fig5A). To confirm that cell death occurred by apoptosis, DNA fragmentation was determined by PI labeling followed by flow cytometric measurement of the percentage of nuclei with hypodiploid DNA content, as previously described.31 This method allows defining four regions within a flow cytometric cell cycle histogram: a major diploid peak (G0/G1), a small hyperdiploid region (S), and a minor tetraploid peak (G2/M). Cells in the region below the G0/G1 peak, designated A0, are cells undergoing apoptosis-associated DNA fragmentation. In noninfected quiescent PAEC cultures the percentage of cells in the A0region varied between 1% and 7%. This percentage was not modified, when PAEC were transduced with rAd.A20 or rAd.β-gal (assessed 48 hours following infection; Fig 5B, left panel). Similarly, this percentage was not modified in NI, rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC when treated with CHX or TNF alone (data not shown). Upon treatment with CHX and TNF, the percentage of apoptotic cells increased to 30% to 40% in the NI or rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC, whereas it remained comparable to control cells in A20-expressing PAEC (Fig 5B, right panel). These later results paralleled those obtained with the crystal violet uptake, thus validating its use for further experiments. Taken all together, our results show that A20 serves two functions in EC: its expression downregulates EC activation through the inhibition of NF-κB and protects from TNF-induced programmed cell death.

(A) Overexpression of A20 rescues CHX-sensitized EC from TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected, rAd.A20-, and rAd.β-gal–infected confluent monolayers of PAEC were treated 48 hours following infection with 100 U/mL of TNF in the presence or absence of 2 μg/mL of CHX. Seven hours following treatment, cell viability was assessed using a vital dye (crystal violet) uptake assay as described. Results are expressed as percentage of survival compared with NI, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells and are representative of three independent experiments. A20 expression significantly protects PAEC from CHX/TNF-induced cytotoxicity. No viable cells were seen in NI or rAdβ-gal–infected PAEC treated with CHX/TNF, as opposed to more than 60% to 70% viability in rAd.A20-infected PAEC treated or not with CHX (2 μg/mL) 30 minutes before the addition of TNF (100 U/mL). (B) Overexpression of A20 prevents apoptotic fragmentation of cellular DNA in CHX- and TNF-treated PAEC. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with either rAd.β-gal or rAd.A20 were treated with CHX (2 μg/mL) or TNF (100 U/mL) either alone or in combination for 7 to 8 hours. Cells were then obtained and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation as described in Materials and Methods. The region below the G1/G0 peak, designated A0, represents cells undergoing apoptosis with fractional DNA content and is presented as a percentage of the total events collected. Results obtained correlated with the crystal violet uptake data, validating its use for further experiments.

(A) Overexpression of A20 rescues CHX-sensitized EC from TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected, rAd.A20-, and rAd.β-gal–infected confluent monolayers of PAEC were treated 48 hours following infection with 100 U/mL of TNF in the presence or absence of 2 μg/mL of CHX. Seven hours following treatment, cell viability was assessed using a vital dye (crystal violet) uptake assay as described. Results are expressed as percentage of survival compared with NI, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells and are representative of three independent experiments. A20 expression significantly protects PAEC from CHX/TNF-induced cytotoxicity. No viable cells were seen in NI or rAdβ-gal–infected PAEC treated with CHX/TNF, as opposed to more than 60% to 70% viability in rAd.A20-infected PAEC treated or not with CHX (2 μg/mL) 30 minutes before the addition of TNF (100 U/mL). (B) Overexpression of A20 prevents apoptotic fragmentation of cellular DNA in CHX- and TNF-treated PAEC. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with either rAd.β-gal or rAd.A20 were treated with CHX (2 μg/mL) or TNF (100 U/mL) either alone or in combination for 7 to 8 hours. Cells were then obtained and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation as described in Materials and Methods. The region below the G1/G0 peak, designated A0, represents cells undergoing apoptosis with fractional DNA content and is presented as a percentage of the total events collected. Results obtained correlated with the crystal violet uptake data, validating its use for further experiments.

Expression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-transduced EC overcomes sensitization to TNF-mediated apoptosis.

Overexpression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis as confirmed using the flow cytometric analysis of DNA content as well as crystal violet uptake (Fig 6A and C). Having established that A20 prevents TNF-mediated apoptosis in EC even though it inhibits activation of NF-κB, we tested whether sensitization to TNF-induced apoptosis when NF-κB is inhibited by I κBα would be overcome by the expression of A20. PAEC were cotransduced with two rAd. (rAd.IκBα and rAd.A20 or rAd.β-gal) at a combined MOI of 1,000 that achieves significant expression of both transgenes in cultured PAEC as confirmed by Northern blot analysis testing for mRNA expression of both the IκBα and the A20 transgenes (Fig 6B). At this MOI, cytotoxicity remained below 10% of the cultured cells when assessed by an LDH enzyme release assay, used as an indicator of membrane rupture. Released enzyme was assayed using a commercially available test system (CytoTox 9600 non-radioactive cytotoxicity kit; Promega, Madison, WI) and the data obtained evaluated according to the manufacturer's instructions (data not shown). At this MOI, PAEC cotransduced with both the rAd.IκBα and the rAd.A20 were protected from apoptosis when stimulated with TNF (Fig 6C). In contrast, PAEC expressing IκBα alone underwent apoptosis under the same conditions. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]; Fig 6C). The effect of A20 is dominant; the EC are rescued from sensitization to TNF-mediated apoptosis by IκBα. These results are in contrast with those of Beg and Baltimore1 in which A20 expression was not able to rescue RelA−/− negative fibroblasts from TNF-mediated cytotoxicity. We suggest that one possible reason for the difference in our findings may be that we performed our studies in EC, whereas the other studies quoted used other cell types.

(A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

(A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have established that the A20 gene can classify within the category of cytoprotective genes in the endothelium, ie, genes that are upregulated in response to inflammatory stimuli such as TNF and act to protect EC from apoptosis and to limit the damage associated with activation.32 Indirect in vivo evidence for such an effect is suggested by our studies in a hamster heart to rat xenotransplantation model.33 We have shown that in grafts that achieve long-term survival, EC express A20. This expression is correlated with the absence of signs of activation or apoptosis. In contrast, EC in rejected grafts do not express A20 and show evidence of activation and apoptosis. Presumably A20 has the same functions in vivo as in vitro: suppression of EC activation and protection from apoptosis.

We confirm that adenoviral-mediated overexpression of A20 in EC acts as a potent inhibitor of EC activation by inhibiting at the transcriptional level the upregulation of several genes (expressed within their DNA context) implicated in the acquisition of the EC of a proinflammatory phenotype.34 We further show that the inhibitory effect of A20 upon EC activation is related to the blockade of the transcription factor NF-κB at a level upstream of IκBα degradation. This effect is so far specific; the expression of A20 in the EC did not have any effect on the SP-1 or cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element (CRE) transcription factors. Indeed, A20 expression did not affect the induction by the viral protein c-tat of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reporter that depends on SP-1 for its induction.7 In addition, the expression of A20 did not modify the binding of the transcription factor CRE in EMSA (data not shown) or affect the upregulation of the immediate-early response gene junB, a member of the AP-1 transcription factors that is transcriptionally regulated by CRE-like and STAT family proteins.28,30 These results do not preclude a potential effect of A20 on other transcription factors. Indeed, a report in the literature shows that expression of A20 inhibits the induction of an AP-1–dependent reporter in a breast tumor cell line.27However, if such an inhibition occurs also in EC, it would need to happen in a manner that does not alter AP-1 binding in EMSA. Nuclear extracts from rAd.A20 and rAd.β-gal–infected PAEC before and after TNF stimulation showed similar binding to a consensus AP-1 radiolabeled oligomer (data not shown). The effect of A20 in EC upon AP-1 transactivating properties still needs further analysis. A different effect on AP-1–mediated transcription in EC, as opposed to the breast tumor cell line, would not be surprising. Differences in the function of A20 according to the cell type have been reported, ie, A20 overexpression protects B cells but not the breast carcinoma cell line MCF7S1 against serum starvation-mediated apoptosis.14 27

The precise mechanism by which A20 inhibits the signaling pathway leading to NF-κB activation is yet to be determined. The inhibitory effect of A20 being localized to the Zn-finger domains of the A20 molecule35 (and manuscript in preparation), which can bind high levels of the known antioxidant element Zn, might suggest an antioxidant mechanism.36,37 Antioxidants, such as pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), are potent inhibitors of NF-κB activation, and like A20 act at a level upstream of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation.22,38 Alternatively, A20 could interact through its Zn-binding domains39,40 with a molecule(s) critically implicated in the signaling that leads to NF-κB activation. A recent report showed that A20 interacts through its N-terminus domain with the TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAF)-1 and TRAF-2.35 In the model proposed by the authors, A20 interacts in human cells with TRAF-1 that serves as an anchor to associate it to TRAF-2 and can then interrupt TNF-mediated signaling and NF-κB activation. However, TRAF-2 is only implicated in TNF and CD40-mediated NF-κB activation,35,41,42 and thus likely does not explain the inhibitory effect to the other agonists used in our study. We rather favor that the inhibitory effect of A20, as already suggested, would affect both a TRAF-2–dependent and TRAF-2–independent pathways.35 To explain the agonist-independent nature of the inhibitory effect of A20, one has to hypothesize that its interaction with a key signaling molecule(s) should occur at a level that is common to all stimuli studied. Antiapoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2, have been shown to interact with molecules involved in signaling pathways such as p21Ras, p23R-Ras, and Raf-1 kinase43-45 to mediate their antiapoptotic effect. Bcl-2, which has an effect similar to A20 in blocking NF-κB activation and preventing apoptosis in EC (A.Z. Badrichani et al, in press), interacts with Raf-1 kinase and targets it to the outer mitochondrial membrane. This translocation potentially brings Raf-1 kinase into proximity with specific substrates that are relevant in the life-death balance of the cell.46-48 In support of this hypothesis, Vincenz et al49 have recently shown using the yeast two-hybrid system, that A20 associates with the 14-3-3 proteins in an isoform-specific manner. These 14-3-3 proteins function as chaperone and adapter molecules bridging A20 with other molecules, namely, the signaling molecule c-Raf that coimmunoprecipitates with A20 in a 14-3-3–dependent manner.49

In addition, we were able to show that expression of A20 in the EC protects them against TNF-mediated apoptosis, a function that had not yet been clearly shown in those cells. This result is of importance as it shows that effective inhibition of NF-κB could be achieved, at least in EC, without sensitizing these cells to TNF-mediated apoptosis. The dominant effect of A20 over IκBα expression paralleled results achieved with antioxidants, which when added to IκBα-expressing EC prevent them from undergoing TNF-mediated apoptosis (C.J. Wrighton et al, personal communication, September 1995), further pointing to potential similarities between A20 and antioxidants.

From a therapeutic point of view, blockade of NF-κB has been suggested as a possible approach to two types of problems that represent opposite sides of the same coin. First, inhibition of NF-κB in EC could be used to prevent the proinflammatory consequences of EC activation, which have been implicated in several pathologic conditions including allograft and xenograft rejection.34,50,51 To achieve this goal, a method to block NF-κB is needed that would not sensitize the cells to TNF-induced apoptosis and even protect them against it. Indeed, EC loss would expose the subendothelial matrix, which would be equally as detrimental as the consequences of EC activation itself. Expression of a gene such as A20 that inhibits inflammatory reactions and still protects the cells from death may achieve this purpose. We suggest that any such NF-κB inhibitory agent may have to act upstream of IκBα phosphorylation and degradation52-55 and inhibit the effects of reactive oxygen species and the activation of proteases and caspases that are prerequisites for activation of NF-κB and are part of the molecular machinery leading to apoptosis.52,56-58 Second, inhibition of NF-κB has been suggested as one approach to using TNF for tumor therapy by rendering the cells sensitive to TNF-mediated apoptosis.1 Our data serve to qualify these suggestions. To achieve this goal it would be critical to use an inhibitor such as IκBα that acts directly and solely on NF-κB to prevent activation. Therapeutic agents such as antioxidants, which were proposed as one possible agent to sensitize tumor cells to TNF-mediated apoptosis, or A20 would not be suitable. Although antioxidants and A20 inhibit NF-κB, their antiapoptotic properties are dominant over sensitization to TNF-induced apoptosis, and thus the very effect one would like to achieve with TNF would not be attained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank E. Csizmadia for preparation of primary PAEC; Dr Robert Gerard for the rAd.β-gal control adenovirus and for the pAC.CMV transfer vector; Dr V. Dixit for providing the rAd.A20 and the anti-A20 MoAb; Drs E. Hofer, R. de Martin, T. Collins, and U. Rulter for providing the IL-8, IκBα, VCAM-1, and junB probes; Dr W.W. Hancock for helping in the immunohistochemistry experiments; and Dr J. Anrather for helpful discussions.

Supported by a grant from Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland. F.H.B. is a paid consultant to Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Address reprint requests to Christiane Ferran, MD, PhD, SCI, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 99 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 3. (A) Northern blot analysis of E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, and IκBα gene induction. PAEC were noninfected (NI), rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected at a MOI of 500 as in Fig 1. Forty-eight hours following infection, PAEC were either left nontreated (C) or were stimulated with TNF (T) (100 U/mL), LPS (L) (100 ng/mL), or PMA (P) (5.10−8 mmol/L). A20, E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, IκBα, and GAPDH steady-state transcript levels were quantitated in these samples by Northern blot analysis using α-[32P]–dATP–labeled homologous or cross-reactive cDNA probes as described in Materials and Methods. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC (confirmed by Northern analysis for A20 mRNA) significantly inhibits E-selectin, VCAM-1, and IκBα gene induction (>80% to 90%) following stimulation by TNF, LPS, and PMA as compared with high level of induction in either NI cells or rAd.β-gal–infected cells. A20 expression also achieved significant inhibition (>70%) of IL-8 gene induction. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Inhibition of cell-surface expression of the EC-specific adhesion molecule E-selectin. Confluent PAEC in 96-well microtiter plates were infected as in (A). Triplicate wells of PAEC were either untreated (C) or treated with the same stimuli as in (A) extended to α-thrombin (Th) and H2O2 (H) (300 μmol/L). Expression of the E-selectin protein was analyzed by ELISA 4 hours following stimulation. Results confirm and extend to α-thrombin and oxidative stimuli, the previous mRNA results, by showing that A20 abrogates surface-expression of E-selectin in PAEC for all stimuli tested. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744003aw.jpeg?Expires=1767868300&Signature=V2PRDSDJsqzUzi-rEIg4NxCRewMd92ogV7WbjCtJpoxzxbDusSiJmqcnLkZ0hZC7SfC8HQvfV9jhGmkwvXBDa-RYfPQ78-NzJNmTV5MfLYBaS4-wU6r-68ELZb0AR9IpIS~xSFjvD8XMqDlzdTb3pR1VsHtj2MoAa-jCJZvTBVLPr80GXrbMOyR2MToMTEHdT7HLaErQmNXjayhy9T~SeN8lyeWtquS4-c9hK1Fo~pCeYPn6JFv0pvYLaU8iLLpOKqC~IynH-8LuXBrvpyXxIUDg9ajwr~kauKJcJhisTei63iiDQLzYMNTp39JZNJPj0vBcei3UN1Q3pdv~G7y9KA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 3. (A) Northern blot analysis of E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, and IκBα gene induction. PAEC were noninfected (NI), rAd.A20, and rAd.β-gal–infected at a MOI of 500 as in Fig 1. Forty-eight hours following infection, PAEC were either left nontreated (C) or were stimulated with TNF (T) (100 U/mL), LPS (L) (100 ng/mL), or PMA (P) (5.10−8 mmol/L). A20, E-selectin, VCAM-1, IL-8, IκBα, and GAPDH steady-state transcript levels were quantitated in these samples by Northern blot analysis using α-[32P]–dATP–labeled homologous or cross-reactive cDNA probes as described in Materials and Methods. Results show that A20 expression in PAEC (confirmed by Northern analysis for A20 mRNA) significantly inhibits E-selectin, VCAM-1, and IκBα gene induction (>80% to 90%) following stimulation by TNF, LPS, and PMA as compared with high level of induction in either NI cells or rAd.β-gal–infected cells. A20 expression also achieved significant inhibition (>70%) of IL-8 gene induction. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Inhibition of cell-surface expression of the EC-specific adhesion molecule E-selectin. Confluent PAEC in 96-well microtiter plates were infected as in (A). Triplicate wells of PAEC were either untreated (C) or treated with the same stimuli as in (A) extended to α-thrombin (Th) and H2O2 (H) (300 μmol/L). Expression of the E-selectin protein was analyzed by ELISA 4 hours following stimulation. Results confirm and extend to α-thrombin and oxidative stimuli, the previous mRNA results, by showing that A20 abrogates surface-expression of E-selectin in PAEC for all stimuli tested. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744003bx.jpeg?Expires=1767868300&Signature=Ds-2QjaaTqE-6CYo0wl3FlHeAtkeStVo80Sw8aJtkU-w4dQIapOC9A9Ts2CCJ2hJFCJq9taICtdwiojAULeec1QrTrIeAlV9lLNY3nutqjS7hRue68hCAxkNpBdEHDyxR1-nvJa276-PTRIp5xWesycdl0zp6SPBzRD8KNCeXGX2EUAnzOAd3B6RyaqZ7tbVuhpjspF38aHphLfgNfNMqS2ug5i9Wbyq9Z5MCDdljvBrjVVxAAQILrovQSwk05oTLY9tAuilMyOLXHrAWZcLjkx2SrTHzzxisxyY6wEE0GzwsWSouD2mErUgwY7qukj0fxWNQqFDRaTAtusXHHXb9w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. (A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744006ax.jpeg?Expires=1767868300&Signature=O4ECIc65usltJKuXv1gC-k9dEQNTG-Pm0SuGrnXN8rkVyJ1LKqUe6WWOrND7tcYnvN2lmcQx0dy5VnADuIylQt9w8phytfxG7q4pbW8YRf5mOFcZIaGp9~dysE86dXJLiIzNR6i2zRsBPoi4a3CKZKxkbSW5djejdnKtwMkTEItmpcZLQMHREo4vyE0qavCRsCrxizgQTA9JFNzNss19KnIwuqOLDYijPcicvQcWimzfK3Uya9wMEeKOun3rVLV56CF~Ru7n1-UQvm7R27e4WX2sZs5-oZSQaNl7BU03fs1gDlXJYZyhx7h5JaLfWozRb57t5EFVt9KerUWpCzKRQA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. (A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744006bw.jpeg?Expires=1767868300&Signature=udHP3Y-Ps67loeHfHHHJ8suz9Ksnxuz~Rkw5Iesqu0GIzRBO1RL3ADtXfFSuIW5vgAXCxHWu2pY0F3yFJmK8gGkFyvXkvDbzeF4d-HZdUj1H6sKG~PVMG0LVr6l~CqYeZDLqSlxLzMxtnQwPe4fZmZL45oyYK9fDJiBcLmrfJJ5Azb7TqiT-Kf-llifwQIsHBC5e2i2ezBht96VmNhX30oNrDSYiCNmX5Lh4kQtyoh0ZNomZMhBilp0EXEKbAGp66b1IklZGmr7GgyZ~9~FpBrx3n6ouByS23A8Ts0w52nGPqdr~ofvqVB8nz~NuPFnX6M9vqz90jK2PMjdWAu-qtA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. (A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744006cx.jpeg?Expires=1767868300&Signature=DmiTeIJ22zfVE3o25~X2obzW0BNm9SawPomyMn8riCbCEF-tIeSCpXmD2GdsnuWLIZwctZ5O7jyBt8n~S1ik-6TvB69dmyl~p7VbH0mRLqw1Y906lQTp6qEvVvX5blp8tWFhKq96Z3fTb6wAJT5ovJ7bNW1tGtc3v~xoCGVAtXTARqZxDag9nhI0Rsw~aRJJyO3iYKInWrqxpYIX0gCRtZVqvjckyWyQJrXYibRS9pLpaiPCyMkFTx9S~tuE8YH~mDO7RcSbhj40J92~UqHAmbrOszW30c0xZnbW31XF-NeYBeBokvOMiqO-~KXxC~wDR~D00xC2EWBfdbzeRreWeA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. (A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744006bw.jpeg?Expires=1767868301&Signature=IQ5vOPPpzBnw84zjL-1BT-aCoRM5nk1AxLYDSeu2UJqGpy6dJGZoI8C0Eue~qd5pxyfdWxz6wnBwnfW5Afcm2biMJ8qK~IzB7MXxg8UxwYFyutg7R0GHv2E4XsOX0Qz6hBj6v9H4jVojUdbMUdZ3kP~URMWs1SOhdzmRDZGNzMuCcZDkGfZv1N3vE-SDJ~kdl9YWr2pnX6ix-6mbDROIdfBJSp5yQ8Y4qltPkfwnd6QohJWSP6s2kXygPlJvqPdoXl2P4OKzOGhxV3JGrAQKzKdVmwr0SuFf9joMmDPJmp5lqu9N76b-n9ERR5OwIGT2JkXOfeu~f~JnF8fWtIgIuw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. (A) Expression of IκBα in PAEC sensitizes them to TNF-mediated apoptosis. Noninfected or rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC were treated for 7 hours with TNF (100 U/mL). Cells were then obtained as described and assessed for apoptosis-induced DNA fragmentation. TNF treatment did not affect the percentage of cells in the A0region, whereas this percentage was increased to 42% in IκBα-expressing PAEC. (B) Infection of cultured PAEC with rAd.A20 and rAd.IκBα results in the coexpression of both transgenes as assessed by Northern blot analysis. (C) Coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected EC reverts their phenotype to resistance against TNF-mediated apoptosis. PAEC were cotransduced with the rAD.IκBα at MOI of 500 for each virus. Noninfected PAEC or PAEC infected with the rAd.IκBα (500 MOI) alone or in combination with the rAd.A20 (500 MOI) or rAd.β-gal (500 MOI) were treated with TNF for 7 hours, after which time cell viability was assessed by crystal violet uptake. Results show that coexpression of A20 in rAd.IκBα-infected PAEC results in a significant increase in cell viability following TNF treatment (60% ± 2) as opposed to cells cotransduced with the rAd.β-gal, where only 19% of the cells were still viable (a percentage that is not significantly different from the cells transduced with the sole rAd.IκBα [28% of viable cells]). Results are also expressed as percentage of survival compared with the noninfected, nontreated (control) PAEC whose values were considered to represent 100% of cell survival. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/7/10.1182_blood.v91.7.2249/3/m_blod40744006cx.jpeg?Expires=1767868301&Signature=bevdP9EMqYviMtUcapw6toVUihXScveQ3VeDa0z9VYI8R4Q1HhPb9Nz-sR4K1Fgxl5YyTKl7ZvlrFvZVAkwBt4P1wCX-GUDL59VPnOlH6DUFgVybLM34rLbFjQ~IvdUhijGcbAa1dJDReajOKlSPDtmno8NeipTiwU0KLNOPoK5VQIDITRtKYwXRQgcbGgtSWDhxdS3GaSFuNYZHRTH66wL0mDEQC7MbungmJ7XHVtjDm7wvbAXIST3MAbLrgnsMx9QL2kvDGwOeRe9TtM40JnyFhsdTYcEOEt2sb8hUebvSWQvUDfMSco31qhfB~F3xAXXD6B9clgfLUBREBU8G8A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)