Typical acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is associated with expression of the PML-RARα fusion protein and responsiveness to treatment with all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). A rare, but recurrent, APL has been described that does not respond to ATRA treatment and is associated with a variant chromosomal translocation and expression of the PLZF-RARα fusion protein. Both PML- and PLZF-RARα possess identical RAR sequences and inhibit ATRA-induced gene transcription as well as cell differentiation. We now show that the above-mentioned oncogenic fusion proteins interact with the nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR and, in comparison with the wild-type RARα protein, their interactions display reduced sensitivities to ATRA. Although pharmacologic concentration of ATRA could still induce dissociation of N-CoR from PML-RARα, it had a very little effect on its association with the PLZF-RARα fusion protein. This ATRA-insensitive interaction between N-CoR and PLZF-RARα was mediated by the N-terminal PLZF moiety of the chimera. It appears that N-CoR/histone deacetylase corepressor complex interacts directly in an ATRA-insensitive manner with the BTB/POZ-domain of the wild-type PLZF protein and is required, at least in part, for its function as a transcriptional repressor. As the above-noted results predict, histone deacetylase inhibitors antagonize oncogenic activities of the PML-RARα fusion protein and partially relieve transcriptional repression by PLZF as well as inhibitory effect of PLZF-RARα on ATRA response. Taken together, our results demonstrate involvement of nuclear receptor corepressor/histone deacetylase complex in the molecular pathogenesis of APL and provide an explanation for differential sensitivities of PML- and PLZF-RARα–associated leukemias to ATRA.

ACUTE PROMYELOCYTIC leukemia (APL) is associated with the t(15;17)(q22;q21) reciprocal chromosomal translocation that causes the fusion of the retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) locus with a gene of unknown function called PML (for promyelocytic leukemia) and expression of PML-RARα chimeric proteins in all leukemic cells.1-4 The wild-type PML protein localizes onto nuclear bodies (NBs; also called PML oncogenic domains or PODs).5-7 Expression of the PML-RARα chimeric protein causes delocalization of PML and other components of NBs to a microspeckled nuclear structure and differentiation of APL cells with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) results in restoration of their normal localization in NBs.5-8 At present, it is not clear what relationship, if any, this phenomenon has to the pathogenesis and treatment of APL.

Expression of the PML-RARα protein in transgenic mice results in the development of APL, which, as the human disease, can be induced into remission by ATRA treatment.9 These results and studies with APL cells in vitro, or cells exogenously expressing PML-RARα, suggest that this oncoprotein is also a primary target of ATRA action.10 11 Therefore, in addition to being the first human cancer to be successfully treated with differentiation therapy, APL is also the only example of a successful application of a therapy targeting the activities of a specific oncoprotein.

To date, three other APL-associated translocations of the RARα gene have been characterized at the molecular level. The t(5;17)(q35;q21),12 t(11;17)(q23;q21),13,14and t(11;17) (q13;q21)15 fuse RARα to nucleophosmin (NPM), promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF), and nuclear mitotic apparatus (NuMA) genes, respectively. So far, the t(5;17)(q35;q21) and t(11;17)(q13;q21) have only been reported in index cases and, as APL with t(15;17), appeared to respond to treatment with ATRA.12,15 In contrast, APL with t(11;17)(q23;q21) has been reported on recurrent basis, albeit at very low frequency, and has been found to be consistently unresponsive to ATRA therapy.16 17The molecular basis for the lack of response of this APL variant to ATRA is not understood.

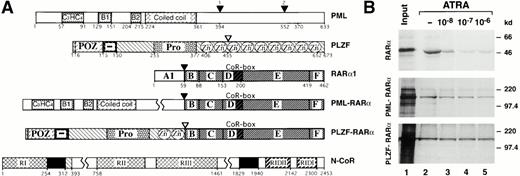

The PLZF gene encodes a protein with N-terminal BTB/POZ-domain and nine C-terminal Krüppel-like Zinc(Zn)-fingers.13 The PLZF-RARα fusion protein consists of the N-terminus of the PLZF protein, including two of its nine Zn-fingers linked to the DNA (region C) and ligand binding (region E) domains of the RARα protein (see Fig 1A for schematic representation). Although PLZF, PML, NPM, and NuMA are not structurally related, it is worth noting that RARα fusion proteins possess identical RARα sequences, which include the DNA, corepressor, coactivator, and ATRA binding regions (see below). Interestingly, localization of the PML protein and integrity of NBs remain undisturbed in APL cells expressing either PLZF-RARα18 or NuMA-RARα15 proteins. Nevertheless, both PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα localize to the same microspeckled structures and the wild-type PLZF protein colocalizes completely with the PML-RARα oncoprotein in APL cells.18

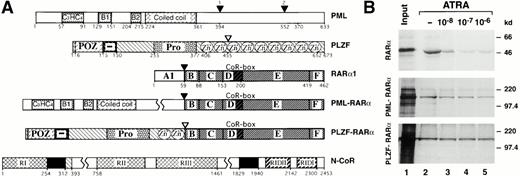

Differential ATRA sensitivities of N-CoR association with RARα and its PML and PLZF fusions. (A) Schematic representation of PML, PLZF, RARα1, PML-RARα, PLZF-RARα, and N-CoR. RI, RII, and RIII, N-CoR repression domains. RIDII and RIDI, N-CoR interaction domains with RARα. CoR-box, corepressor interaction domain in the RARα. Solid boxes represent the Sin3 interaction domains of N-CoR. Numbers correspond to the amino acids flanking various functional domains, indicated with different patterns, within a given protein. Fusion points between RARα and PLZF or PML are indicated by arrowheads. (B) Binding of RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα to GST-N-CoR corepressor (amino acids 1679-2453). Radiolabeled receptors, synthesized in vitro, were incubated with immobilized GST-N-CoR over a range of ATRA concentrations, as indicated. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Differential ATRA sensitivities of N-CoR association with RARα and its PML and PLZF fusions. (A) Schematic representation of PML, PLZF, RARα1, PML-RARα, PLZF-RARα, and N-CoR. RI, RII, and RIII, N-CoR repression domains. RIDII and RIDI, N-CoR interaction domains with RARα. CoR-box, corepressor interaction domain in the RARα. Solid boxes represent the Sin3 interaction domains of N-CoR. Numbers correspond to the amino acids flanking various functional domains, indicated with different patterns, within a given protein. Fusion points between RARα and PLZF or PML are indicated by arrowheads. (B) Binding of RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα to GST-N-CoR corepressor (amino acids 1679-2453). Radiolabeled receptors, synthesized in vitro, were incubated with immobilized GST-N-CoR over a range of ATRA concentrations, as indicated. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

RARs are ligand regulated transcription factors that affect many physiologic processes,19-21 including hemopoiesis.22 They exert their effect on gene expression by binding as heterodimers with the retinoid X receptors (RXRs) to the retinoic acid response elements (RAREs) located in promoter/enhancer regions of specific genes and either activating or repressing basal transcription.23-26 In the absence of ATRA, RARs remain associated with the nuclear receptor corepressors, N-CoR (negative coregulator)27 or SMRT (silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid-hormone receptors),28 and repress basal transcription. Both N-CoR29,30 and SMRT31 have been shown to associate with the mammalian homologues (Sin3A and Sin3B) of yeast global transcriptional repressor SIN332-34 and histone deacetylase35 (HDAC1 or 2) and to repress transcription through histone deacetylation, rendering the nearby chromatin inaccessible to transcriptional activators and/or basal transcription factors. Sin3A, Sin3B, and histone deacetylases have also been implicated in transcriptional repression by Mad/Max30,36,37 or Max/Mxi29 heterodimers.

Both PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα can bind to an RARE as homodimers or, in combination with RXR, as multimeric complexes.38-40 Both fusion proteins inhibit the activity of the wild-type RARα in a dominant negative manner.1,2,8,39-41 Previous studies have shown that the dominant negative activities of PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα on ATRA-inducible transcription are inherent properties of the RARα chimeric proteins and are not observed upon expression of N-terminal truncation of RARα and/or N-terminal PLZF or PML sequences.1,2,41 Because the PML- and PLZF-RARα chimeric proteins bind ATRA with near wild-type affinities,40 we set out to test whether their impaired abilities to be activated by ATRA could be due to inefficient association with RARα coactivators and/or too strong interaction with the corepressors. We have now shown that, in contrast to RARα and PML-RARα, the association of PLZF-RARα with N-CoR is insensitive to ATRA. This is due to a ligand-insensitive association of N-CoR corepressor with the N-terminus of the wild-type PLZF protein. Furthermore, the ATRA sensitivity of N-CoR association with the PML-RARα is lower than with the wild-type RARα, ie, sensitive to pharmacologic but not physiologic concentrations of ATRA. These results support the above-noted hypothesis and suggest that abnormal interactions between RARα fusion proteins and nuclear receptor corepressors play a major role in the pathogenesis of APL and its response to ATRA treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression plasmids and glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins.

Constructions of PLZF, 5′PLZF (N-terminal region of PLZF, amino acids 1-455), PLZFΔPOZ (PLZF deleted for the BTB/POZ domain, amino acids 1-120), PML-RARα, PLZF-RARα cDNA expression vectors, and GST-PLZF plasmid have been previously described.40,41Mammalian, bacterial, and in vitro expression vectors for the PML,8 full-length and partial N-CoR,30,42HDAC1,35 as well as Sin3A and B36 proteins were described by others. L4-tkluc reporter construct contains four LexA operators with two PLZF target sites (5′-GTACAGTAC-3′), which were derived using PCR from L8-CAT plasmid43 and cloned into the pT109luc44 vector upstream of the minimal HSV-thymidine kinase (tk) promoter and luciferase (luc) gene. The RARE2-tkluc reporter vector was previously described.41 Mammalian two-hybrid expression vectors were derived from pGALO and pNLVP16 plasmids45 by subcloning indicated cDNAs in frame with the coding regions for the GAL4 DNA binding and VP16 activating domains, respectively. The GAL(RE)5-tkluc reporter was derived from the pT109luc plasmid by inserting five copies of the GAL4 DNA binding site upstream of the minimal HSV-tk promoter.

In vitro interaction assays.

All GST fusion proteins were prepared using standard procedures.4035S-methionine–labeled proteins were synthesized in vitro using coupled transcription-translation system, TNT (Promega, Madison, WI), following the supplier's directions. 35S-labeled proteins were incubated with 1 μg GST or a given GST fusion protein (see below for conditions). In the case of 35S-labeled RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα, binding reactions were performed for 2 hours at 4°C in the absence or in the presence of 1 × 10−6 mol/L, 1 × 10−7 mol/L, or 1 × 10−8 mol/L ATRA. Assays were performed in NETN buffer (20 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5% NP-40) at 4°C for 60 minutes with gentle rocking. Glutathione-Sepharose beads were washed five times with H buffer (20 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.7, 50 mmol/L KCl, 20% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40). Bound proteins were eluted in Laemmeli loading buffer and separated on a 5% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Gels were fixed in 25% isopropanol and 10% acetic acid, dried, and exposed to Kodak Biomax film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Anti-Sin3A and anti-N-CoR antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). For coimmunoprecipitation, in vitro translated Sin3A and N-CoR were incubated with a given 35S-labeled protein in NETN buffer for 1 hour at 4°C. Immunocomplexes were isolated by further incubation with an appropriate antibody preadsorbed on protein A/G Sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), washed 5 times in H buffer, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by autoradiography.

Cell culture and transient expression analysis.

Transient transfections using 293T46 or CV-147cells, maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), were performed using either the calcium phosphate precipitation method41 or SuperFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, San Clarita, CA). FCS treated with dextran-coated charcoal was used for all transfection experiments involving subsequent additions of ATRA. Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven β-galactosidase gene expression plasmid (CMV-lacZ) was used as a control for transfection efficiency. Cells were harvested for assaying luciferase and β-galactosidase activities 26 to 48 hours after transfection. Luciferase assays were normalized using units of β-galactosidase activity. Both assays were performed using commercial reagents according to the supplier's recommendations (Promega). Cells were treated with either ATRA at 1 × 10−6 mol/L (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 20 hours alone or ATRA plus 1 mmol/L sodium butyrate (NaB; Sigma). BSM+ DNA (Stratagene) was used as a carrier to equalize the total amount of transfected DNA. In all cotransfection experiments, the total amount of transfected mammalian expression vector was kept constant. All transfections were performed at least three times. The NB-4 cells48 were maintained in RPMI with 10% FCS. Cells were treated either with ATRA alone (500 nmol/L) or with ATRA followed by 1 mmol/L NaB. Cell differentiation was assayed by scoring the percentage of nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT)-positive cells in treated cells versus untreated controls at 2 and 3 days after treatment.

RESULTS

Compared with the wild-type RARα, interactions between N-CoR and APL-associated PLZF- or PML-RARα fusions are less sensitive to ATRA.

Inhibition and stimulation of granulocytic differentiation by dominant negative RARα mutants49,50 (or antagonists of RARα51,52) and RARα-specific agonists,52,53respectively, suggest that granulopoiesis requires activation of RARα transcriptional activity by physiologic concentrations of ATRA. The PML-RARα chimera expressed in APL cells inhibits granulocytic differentiation under physiologic (10−8 mol/L) but not pharmacologic (10−6 mol/L) concentrations of ATRA,54,55 suggesting lower sensitivity to ATRA. The PLZF-RARα chimera appears to be even less sensitive, or completely insensitive, to ATRA, because APL cells with PLZF-RARα16,17 or myeloid cells overexpressing transfected PLZF-RARα56 fail to respond to ATRA. Nevertheless, the wild-type RARα, PLZF-RARα, and PML-RARα possess approximately equal binding affinities for ATRA.40 57 Given this background information, we attempted to test whether the chimeric receptors differ in their binding affinities for nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR and, hence, would display lower responsiveness to ATRA. Using an in vitro interaction assay, we found that, in the absence of ATRA radiolabeled RARα, PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα were specifically retained on a matrix-bound fusion of GST with N-CoR fragment containing amino acids 1679-2453 (GST-N-CoR 1679-2453; Fig1B). Furthermore, over ATRA concentrations ranging from 1 × 10−8 mol/L to 1 × 10−6 mol/L, binding of RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα to GST-N-CoR displayed dramatically different ligand sensitivities. Both RARα and PML-RARα lost most of their N-CoR binding at increasing concentrations of ATRA, although PML-RARα required a higher ATRA concentration to attain a similar degree of dissociation (Fig 1B, compare lanes 2 through 6 between the upper and middle panels). In contrast, binding of N-CoR to PLZF-RARα remained relatively unchanged, even in the presence of pharmacologic concentrations of ATRA (Fig 1B, bottom panel).

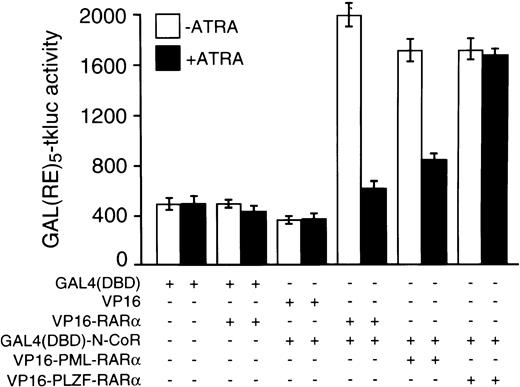

The above-noted in vitro data were fully corroborated by results from in vivo experiments that used the mammalian two-hybrid assay with the N-CoR protein fused to the GAL4 DBD and RARα, PLZF-RARα, or PML-RARα VP16 activation domain fusions. As reflected by the luciferase activities generated from the GAL(RE)5-tkluc reporter vector, strength of in vivo interaction between GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR and VP16-PLZF-RARα was virtually unaffected by 10−6 mol/L concentration of ATRA (Fig 2). In contrast, when compared with the results obtained in the absence of ATRA, the degree of in vivo association between GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR and VP16-PML-RARα was very low at 10−6 mol/L ATRA, and GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR/VP16-RARα interaction was nearly completely abolished with ATRA treatment (Fig2).

Mammalian two-hybrid analysis of interactions between N-CoR and RARα, PML-RARα, or PLZF-RARα and their ATRA sensitivities in vivo. Cotransfections of CV-1 cells with 125 ng of GAL(RE)5-tkluc reporter plasmid, 35 ng of GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR expression vector (or an empty vector), 100 ng of CMV-lacZ internal control, and 125 ng of an expression vector for a given VP16 fusion protein, as indicated, were performed in 24-well plates using calcium phosphate precipitation and approximately 105 cells per well. Where indicated, cells were treated 24 to 26 hours after transfection with 10−6 mol/L ATRA for approximately 20 hours before harvesting. Similar to the VP16-RARα control, cotransfection of an empty GAL4(DBD) vector (pGALO) either with VP16-PML-RARα or VP16-PLZF-RARα did not result in activation of the luciferase gene expression (not shown).

Mammalian two-hybrid analysis of interactions between N-CoR and RARα, PML-RARα, or PLZF-RARα and their ATRA sensitivities in vivo. Cotransfections of CV-1 cells with 125 ng of GAL(RE)5-tkluc reporter plasmid, 35 ng of GAL4(DBD)-N-CoR expression vector (or an empty vector), 100 ng of CMV-lacZ internal control, and 125 ng of an expression vector for a given VP16 fusion protein, as indicated, were performed in 24-well plates using calcium phosphate precipitation and approximately 105 cells per well. Where indicated, cells were treated 24 to 26 hours after transfection with 10−6 mol/L ATRA for approximately 20 hours before harvesting. Similar to the VP16-RARα control, cotransfection of an empty GAL4(DBD) vector (pGALO) either with VP16-PML-RARα or VP16-PLZF-RARα did not result in activation of the luciferase gene expression (not shown).

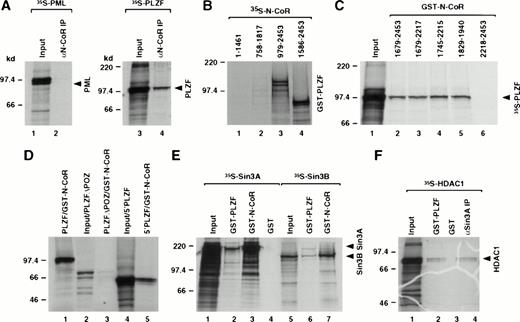

Nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR interacts with the wild-type PLZF, but not with the PML protein.

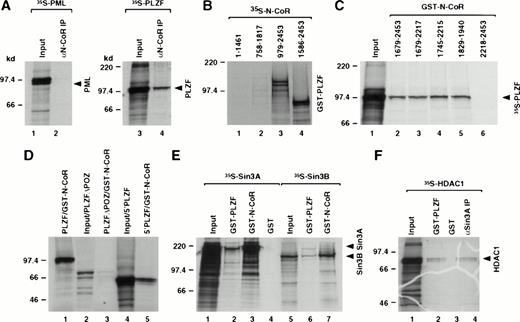

Differential sensitivities of N-CoR interaction with RARα and the two fusion proteins could be due to stabilization of corepressor binding by either PML or PLZF sequences in the fusion proteins. We therefore used in vitro coimmunoprecipitation and GST-pulldown assays to investigate if the wild-type PML and PLZF could associate with the N-CoR protein. Although PML did not interact with N-CoR, we detected interaction between N-CoR and the PLZF protein (Fig3A). We then used various PLZF and N-CoR deletion mutants to identify domains within the PLZF and N-CoR proteins that were responsible for this interaction (Fig 3B through D). The interaction was mapped to the region of N-CoR that overlapped with the previously mapped Sin3 interaction domain29 30 and the BTB/POZ-domain of the PLZF protein. These results were consistent with the data, described in the preceding section, showing ATRA insensitive interaction between GST-N-CoR (amino acids 1679-2453) and PLZF-RARα (containing amino acids 1-455 of the PLZF protein). Because previous studies have shown that N-CoR corepressor associates with certain nuclear receptors as a complex with Sin3A and HDAC, we determined whether PLZF could also interact with those molecules. Using GST-pulldown assays, we find that in vitro PLZF also appears to interact directly with the Sin3A and Sin3B proteins (Fig 3E) as well as HDAC1 (Fig 3F) and, to a lesser degree, also with HDAC2 (data not shown). Nevertheless, the interaction of the Sin3 proteins with PLZF was considerably weaker than with N-CoR. Interaction of PLZF with HDAC1 was also weak, albeit comparable to the interaction of HDAC1 with the Sin3A protein as detected by coimmunoprecipitation in vitro. All interactions appeared to be specific for PLZF, because no signal was detected using just the GST protein as a control. The in vitro association between PLZF and N-CoR, Sin3, or HDAC1 protein was insensitive to ATRA treatment (data not shown).

Mapping of the interaction domains between PLZF and N-CoR. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of N-CoR and PLZF. PML and PLZF were radiolabeled and incubated with in vitro translated N-CoR. After immunoprecipitation with anti–N-CoR antibody (αN-CoR), proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Twenty-five percent of input is shown (input). (B) N-CoR mutants (as indicated by amino acids numbers) were labeled in vitro with 35S-methionine, incubated with GST-PLZF affinity matrix, and analyzed in pulldown assays. (C) Partial N-CoR proteins (delineated by amino acid numbers) were expressed in bacteria as GST fusions and used in pulldown assays for in vitro interaction with radiolabeled PLZF. Ten percent of input is shown (input). (D) Various PLZF mutants, as indicated, were radiolabeled and incubated with GST-N-CoR affinity matrix (amino acids 1829-1940, containing the C-terminal Sin3 interaction domain). PLZF▵POZ and 5′PLZF correspond to PLZF without the BTB/POZ domain and the region of PLZF contained in the PLZF-RARα chimeric protein, respectively. Ten percent input is shown (input). (E) Radiolabeled Sin3A and B proteins were incubated with GST-N-CoR (amino acids 1679-2453), GST-PLZF, or GST affinity matrix and analyzed in pulldown assays. Twenty-five percent input is shown (input). (F) HDAC1 was labeled in vitro with 35S-methionine and subjected to either the pulldown assay with GST-PLZF or coimmunoprecipitation with in vitro translated Sin3A protein and anti-Sin3A antibody (αSin3A). Twenty-five percent input is shown (input).

Mapping of the interaction domains between PLZF and N-CoR. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of N-CoR and PLZF. PML and PLZF were radiolabeled and incubated with in vitro translated N-CoR. After immunoprecipitation with anti–N-CoR antibody (αN-CoR), proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Twenty-five percent of input is shown (input). (B) N-CoR mutants (as indicated by amino acids numbers) were labeled in vitro with 35S-methionine, incubated with GST-PLZF affinity matrix, and analyzed in pulldown assays. (C) Partial N-CoR proteins (delineated by amino acid numbers) were expressed in bacteria as GST fusions and used in pulldown assays for in vitro interaction with radiolabeled PLZF. Ten percent of input is shown (input). (D) Various PLZF mutants, as indicated, were radiolabeled and incubated with GST-N-CoR affinity matrix (amino acids 1829-1940, containing the C-terminal Sin3 interaction domain). PLZF▵POZ and 5′PLZF correspond to PLZF without the BTB/POZ domain and the region of PLZF contained in the PLZF-RARα chimeric protein, respectively. Ten percent input is shown (input). (E) Radiolabeled Sin3A and B proteins were incubated with GST-N-CoR (amino acids 1679-2453), GST-PLZF, or GST affinity matrix and analyzed in pulldown assays. Twenty-five percent input is shown (input). (F) HDAC1 was labeled in vitro with 35S-methionine and subjected to either the pulldown assay with GST-PLZF or coimmunoprecipitation with in vitro translated Sin3A protein and anti-Sin3A antibody (αSin3A). Twenty-five percent input is shown (input).

Repression of transcription by PLZF is mediated, at least in part, through histone deacetylation.

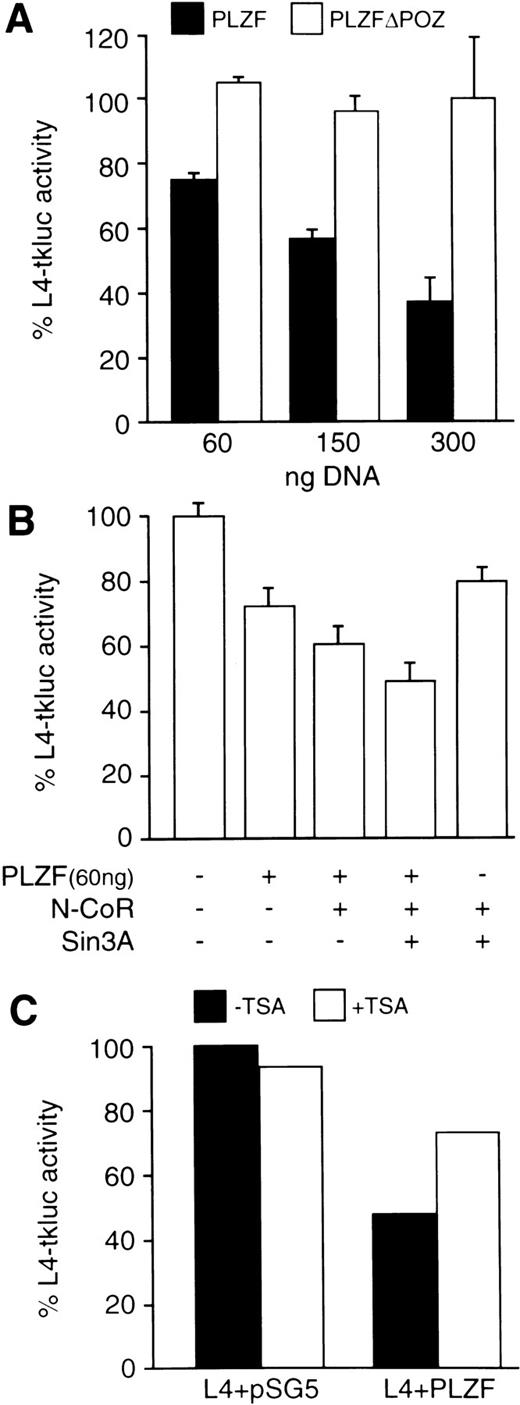

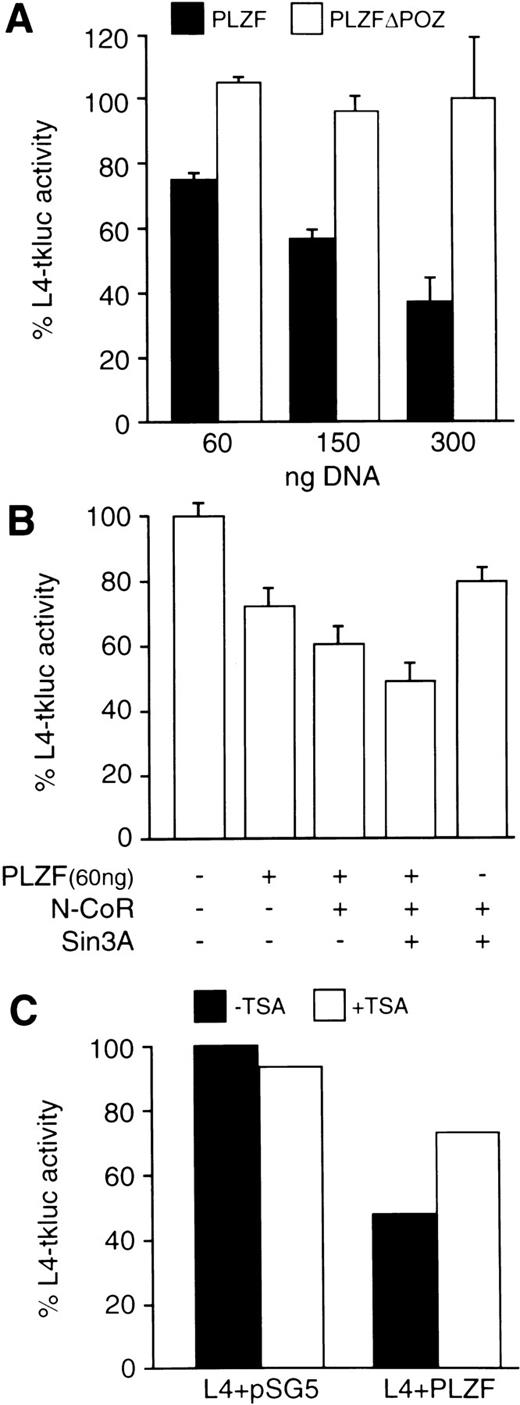

The carboxy-terminal Zn-fingers of the PLZF protein possess DNA binding activity with specificity for 5′-GTACAGTAC-3′ motif, which is present in genomic sequences and, serendipitously, in the LexA operator (Sitterlin et al58 and our unpublished results). Furthermore, the N-terminus of the PLZF protein fused to the Gal4 DBD repressed transcription from a Gal4 binding site.59 We now show that the wild-type PLZF protein, which is transiently expressed in 293T cells, represses transcription from its binding site within the LexA operator located upstream of the minimal (−109 to +52) HSV-tk promoter (Fig 4A). The level of repression increases with increasing amounts of cotransfected PLZF expression vector and is completely dependent on the presence of PLZF BTB/POZ-domain. Cotransfecting N-CoR and Sin3A expression vectors further reduces the transcription from the L4-tkluc reporter in the presence but not in the absence of cotransfected PLZF protein (Fig 4B). Treatment of transfected cells with a histone deacetylase inhibitor, such as Trichostatin A (TSA),60 relieved the repression by about 50% (Fig 4C), suggesting that, in addition to histone deacetylation, the PLZF protein represses transcription through other mechanism(s).

The BTB/POZ domain containing the N-CoR interaction region is required for transcriptional repression by the PLZF protein. Cell transfections were performed in 6-well plates (∼106 cells per well per transfection) using SuperFect reagent (Promega). (A) Increasing amounts (as indicated) of expression vectors for the wild-type PLZF and PLZF▵POZ (solid and open boxes, respectively) were cotransfected with L4-tkluc (400 ng) reporter vector and 50 ng of CMV-lacZ plasmid as a control for transfection efficiency. Results are expressed as the percentage of luciferase activity obtained in the presence of equivalent amounts of cotransfected empty expression vector (pSG5). (B) Cotransfection of PLZF (60 ng), N-CoR (300 ng), and Sin3A (300 ng). Expression plasmids were transfected in the indicated amounts and the percentage of L4-tkluc (400 ng) activity was evaluated as described in (B). (C) Addition of TSA (200 ng/mL), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, relieved repression of the L4-tkluc reporter plasmid expression by the PLZF protein. In this experiment, 300 ng of PLZF expression vector or empty vector (pSG5) control, together with 400 ng of L4-tkluc and 50 ng CMV-lacZ, were cotransfected.

The BTB/POZ domain containing the N-CoR interaction region is required for transcriptional repression by the PLZF protein. Cell transfections were performed in 6-well plates (∼106 cells per well per transfection) using SuperFect reagent (Promega). (A) Increasing amounts (as indicated) of expression vectors for the wild-type PLZF and PLZF▵POZ (solid and open boxes, respectively) were cotransfected with L4-tkluc (400 ng) reporter vector and 50 ng of CMV-lacZ plasmid as a control for transfection efficiency. Results are expressed as the percentage of luciferase activity obtained in the presence of equivalent amounts of cotransfected empty expression vector (pSG5). (B) Cotransfection of PLZF (60 ng), N-CoR (300 ng), and Sin3A (300 ng). Expression plasmids were transfected in the indicated amounts and the percentage of L4-tkluc (400 ng) activity was evaluated as described in (B). (C) Addition of TSA (200 ng/mL), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, relieved repression of the L4-tkluc reporter plasmid expression by the PLZF protein. In this experiment, 300 ng of PLZF expression vector or empty vector (pSG5) control, together with 400 ng of L4-tkluc and 50 ng CMV-lacZ, were cotransfected.

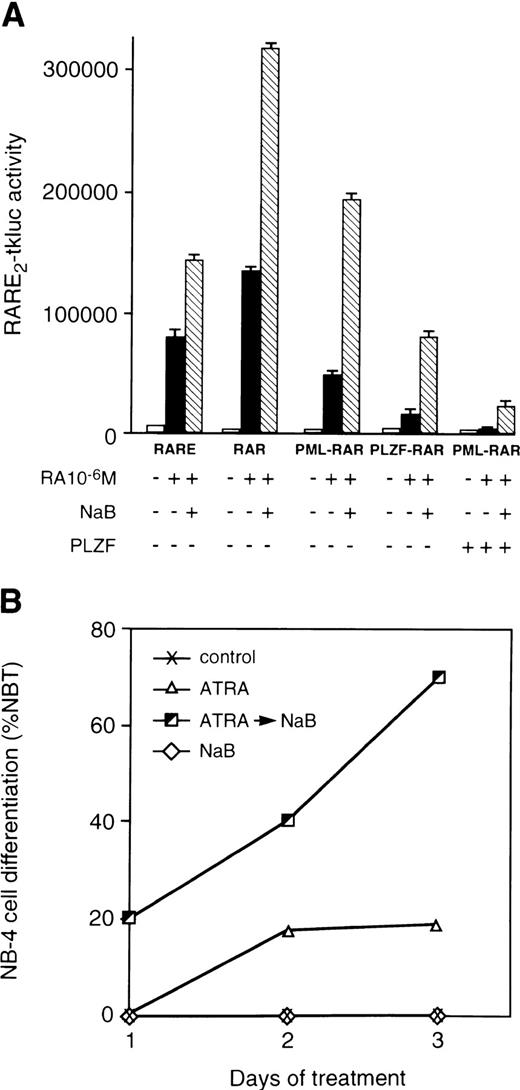

Inhibitory effects of PML- and PLZF-RARα on the activities of the wild-type RARs correlates with the ATRA sensitivity of N-CoR binding by these chimeric proteins and can be alleviated by histone deacetylase inhibitors.

In a number of cell systems, the PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα chimeric proteins were found to antagonize the function of endogenous retinoic acid receptors and/or perform as much less potent activators when compared with the wild-type RARα.1,2,8,39-41 When assayed side by side, PLZF-RARα was a consistently poorer activator of transcription from the RARE2-tkluc reporter than PML-RARα and/or a stronger inhibitor of transcription by the wild-type RARs (Fig 5A). Involvement of histone deacetylation in the mechanism of PML- and PLZF-RARα action is supported by data showing that a known histone deacetylase inhibitor, NaB,61-63 can relieve the repression of ATRA response by these chimeric proteins (Fig 5A). Data obtained using NaB were fully corroborated when another histone deacetylase inhibitor, TSA, was used (not shown). Furthermore, histone deacetylase inhibitors, NaB (Fig 5B) and TSA (data not shown), synergized with ATRA in differentiation of t(15;17)-positive APL cells. It is worth noting that, in the presence of ATRA, other agents, such as hexamethylene-bisacetamide, have been shown to have a rapidly synergistic effect on differentiation of NB-4 cells,64raising possibilities that such compounds may also possess histone deacetylase-inhibiting activities. Combination of ATRA and NaB also synergized to induce differentiation of the PML-RARα–negative human myeloid leukemia HL-60 cell line,65 most likely reflecting stimulatory effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on the activation of the wild-type RARα by retinoids.

Histone deacetylase inhibitor NaB relieves repressing activities of RARα chimeric proteins and synergizes with ATRA in differentiation of APL cells. (A) Transcriptional activities of the wild-type and mutant RARs assayed in 293T cells. Cotransfections were performed with RARE2-tkluc reporter plasmid (200 ng), 50 ng of CMV-lacZ control, and a pSG5 expression vectors for the indicated proteins (50 ng each). ATRA (10−6 mol/L) was added alone or in combination with histone deacetylase inhibitor NaB (1 mmol/L). NaB synergizes with ATRA in alleviating the transcriptional inhibition of RARE2-tkluc reporter by PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα. ATRA alone, or together with NaB, had a considerably lower effect on transcriptional activation by PML-RARα, but not by the wild-type RARα (not shown), when an equal amount of the wild-type PLZF expression vector was cotransfected. All cell transfections were performed in 24-well plates (∼105 cells per well per transfection) using calcium phosphate precipitation. (B) NaB potentiated differentiating effects of ATRA on NB-4 cells. The Y-axis indicates the percentage of NBT-positive cells assayed 2 and 3 days after treatment with 500 nmol/L ATRA, no treatment, or treatment with 500 nmol/L ATRA followed by 1 mmol/L of NaB.

Histone deacetylase inhibitor NaB relieves repressing activities of RARα chimeric proteins and synergizes with ATRA in differentiation of APL cells. (A) Transcriptional activities of the wild-type and mutant RARs assayed in 293T cells. Cotransfections were performed with RARE2-tkluc reporter plasmid (200 ng), 50 ng of CMV-lacZ control, and a pSG5 expression vectors for the indicated proteins (50 ng each). ATRA (10−6 mol/L) was added alone or in combination with histone deacetylase inhibitor NaB (1 mmol/L). NaB synergizes with ATRA in alleviating the transcriptional inhibition of RARE2-tkluc reporter by PML-RARα and PLZF-RARα. ATRA alone, or together with NaB, had a considerably lower effect on transcriptional activation by PML-RARα, but not by the wild-type RARα (not shown), when an equal amount of the wild-type PLZF expression vector was cotransfected. All cell transfections were performed in 24-well plates (∼105 cells per well per transfection) using calcium phosphate precipitation. (B) NaB potentiated differentiating effects of ATRA on NB-4 cells. The Y-axis indicates the percentage of NBT-positive cells assayed 2 and 3 days after treatment with 500 nmol/L ATRA, no treatment, or treatment with 500 nmol/L ATRA followed by 1 mmol/L of NaB.

DISCUSSION

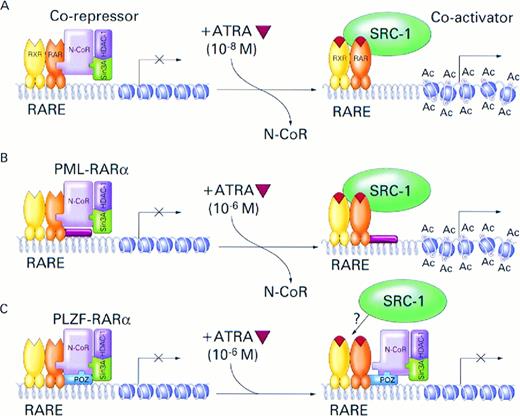

It now appears that the strong inhibitory effect of the PLZF-RARα chimera is based on the ability of its N-terminal BTB/POZ-domain to associate independently, in an ATRA-insensitive manner, with the N-CoR corepressor and possibly also with other components of the nuclear receptor corepressor complex, such as Sin3 and HDAC. Therefore, the PLZF-RARα protein can engage with N-CoR by means of the receptor interaction domain (CoR-box, see Fig 1A) and the PLZF BTB/POZ interaction domain, with the latter being completely insensitive to ATRA. Because PML does not appear to interact with N-CoR, decreased sensitivity of PML-RARα/N-CoR association to ATRA may be due to steric effects that the PML moiety exerts on the N-CoR binding RARα region (CoR-box) of the chimeric protein or some other factors that may interact with both PML and N-CoR and stabilize the complex. In this respect, noteworthy is our previous study reporting interaction and colocalization between PML and PLZF as well as PLZF and PML-RARα proteins (but not PML and PLZF-RARα) in APL cells,18suggesting that PLZF may play a wider role in APL than previously supposed from the study of few patients with the t(11;17)(q23;q21) chromosomal translocation. The hypothesis that PLZF may be such a factor is supported by observation that overexpression of the PLZF protein strongly inhibits responsiveness of the PML-RARα to ATRA as well as ATRA and NaB (Fig 5A). The strong inhibitory effect of PLZF, even in the presence of histone deacetylase inhibitor, is consistent with a model in which transcriptional repression by PLZF is only partially mediated through histone deacetylation. Nevertheless, interaction between PML-RARα and N-CoR remains sensitive to treatment with pharmacologic doses of ATRA providing a mechanism for therapeutic response of APL with t(15;17) to this drug.

Very recently, it has also been shown that PLZF,66 as well as BTB/POZ-domain Zn-finger protein LAZ-3/BCL-6,67 which plays a role in the pathogenesis of diffuse large-cell lymphoma,68,69 interact with another nuclear receptor corepressor, SMRT. In vitro interactions of SMRT with RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα also displayed differential sensitivities to ATRA.66 LAZ-3/BCL-6 can also interact with the N-CoR protein (data not shown), suggesting that both nuclear receptors and BTB/POZ-domain Zn-finger proteins repress transcription through the same general mechanism. These results also provide evidence for a relationship between signalling through distinct families of transcriptional regulators, such as nuclear receptors, BTB/POZ domain Zn-finger proteins, and E-box binding Mad/Max proteins. Because distinct regulators often possess common coregulators, by sequestration of a shared coregulator, activation or repression by a given factor may have the opposite effect on activity of another factor(s). For example, activation of a nuclear hormone receptor by ligand binding causes association of a coactivator, such as CBP (CREB-binding protein), which is also required by a number of other activators, including CREB, AP-1, and STAT-1α.70,71 Depending on the relative affinities of these proteins for CBP and their concentrations, activation of a nuclear receptor by its ligand could inhibit CREB, AP-1, and STAT-1α activities and, hence, signalling through cAMP, Ras, and interferon γ (INFγ) pathways, respectively. Because Sin3/N-CoR/HDAC are also required for transcriptional repression by Mad/Max complex,30,36 37 which is associated with cellular differentiation, the fusion receptors may in part contribute to leukemogenesis by sequestration of these factors and inhibition of Mad/Max activity in favor of growth promoting Myc/Max function.

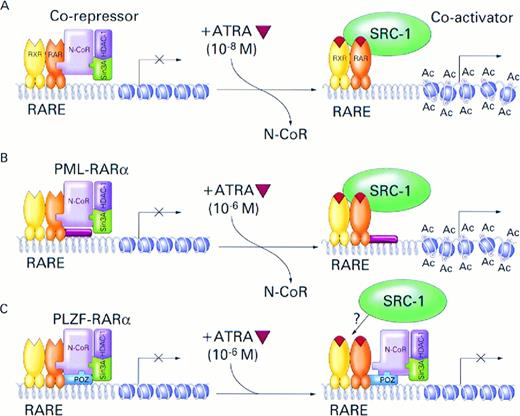

Deregulation of histone acetylation has for some time been thought to be associated with oncogenesis, and histone deacetylase inhibitors were reported to possess anti-tumor activities.72,73 Association of histone acetyltransferase, CBP, with two different leukemogenic translocations, t(11;16)(q23;p13)74 and t(8;16)(p11;p13)75 involving the MLL and MOZ genes, respectively, has also been reported. In summary, our data directly implicate for the first time the nuclear receptor corepressor/histone deacetylase complex in carcinogenesis and provide a plausible mechanism (Fig 6) for the molecular pathogenesis of APL and its response to treatment with ATRA. Central to this model is the observation that nuclear receptor corepressor binding to PML- and PLZF-RARα displays abnormal sensitivity to ATRA, with corepressor/PLZF-RARα association being the least sensitive or not sensitive at all. Because histone deacetylase inhibitors considerably potentiate effects of ATRA on both the activities of the RARα fusion proteins and APL cell differentiation, they may serve as useful adjuncts to ATRA in treatment of APL.

Model for the role of nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR/Sin3A/HDAC1 complex and RARα fusion proteins in the pathogenesis and treatment of APL. (A) In the absence of ATRA, RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα associate with N-CoR/Sin3A/HDAC1 corepressor complex. The associated corepressor/RARα complex acts on chromatin structure by deacetylation of histone tails inducing its reorganization into a repressed state that is inaccessible to basal transcription factors. Binding of ATRA (orange triangle) induces conformational change in the RARα, causing dissociation of the corepressor complex and association of a coactivator, such as SRC-1, with intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity.76Acetylation (Ac) of histone tails disrupts tightly packed and repressed chromatin structure, allowing access of the basal transcription factors and transcriptional activation. Physiologic concentrations of ATRA (10−8) are sufficient to induce this process. (B) In the case of the PML-RARα protein, pharmacologic doses of ATRA (10−6 mol/L) are required to achieve efficient dissociation of the N-CoR corepressor complex from the chimeric protein and transcriptional activation. (C) Because of additional, ligand-insensitive interactions between the PLZF moiety of the PLZF-RARα fusion protein and N-CoR (and possibly also Sin3A and HDAC1), the corepressor/PLZF-RARα complex remains associated even in the presence of pharmacologic concentrations of ATRA and, in the absence of chromatin remodelling by histone acetylation, transcription remains inhibited.

Model for the role of nuclear receptor corepressor N-CoR/Sin3A/HDAC1 complex and RARα fusion proteins in the pathogenesis and treatment of APL. (A) In the absence of ATRA, RARα, PML-RARα, and PLZF-RARα associate with N-CoR/Sin3A/HDAC1 corepressor complex. The associated corepressor/RARα complex acts on chromatin structure by deacetylation of histone tails inducing its reorganization into a repressed state that is inaccessible to basal transcription factors. Binding of ATRA (orange triangle) induces conformational change in the RARα, causing dissociation of the corepressor complex and association of a coactivator, such as SRC-1, with intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity.76Acetylation (Ac) of histone tails disrupts tightly packed and repressed chromatin structure, allowing access of the basal transcription factors and transcriptional activation. Physiologic concentrations of ATRA (10−8) are sufficient to induce this process. (B) In the case of the PML-RARα protein, pharmacologic doses of ATRA (10−6 mol/L) are required to achieve efficient dissociation of the N-CoR corepressor complex from the chimeric protein and transcriptional activation. (C) Because of additional, ligand-insensitive interactions between the PLZF moiety of the PLZF-RARα fusion protein and N-CoR (and possibly also Sin3A and HDAC1), the corepressor/PLZF-RARα complex remains associated even in the presence of pharmacologic concentrations of ATRA and, in the absence of chromatin remodelling by histone acetylation, transcription remains inhibited.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Q.-H. Huang, Z. Chen, L. Wiedemann, T. Enver, J. Licht, and M. Greaves for helpful comments and discussions. We are grateful to P. Chambon, S. Hollenberg, C.D. Laherty, R.N. Eisenman, C.A. Hassig, S.L. Schreiber, C.K. Glass, C.V. Dang, E.R. Fearon, T.H. Rabbitts, M. Lanotte, and M. Yoshida for their generous gifts of molecular clones, expression vectors, antibodies, cells, and drugs that were used in this study.

Supported by The Leukaemia Research Fund of Great Britain, National Institutes of Health (Grant No. CA59936-01), and the Medical Research Council. F.G. and J.Z. were in part supported by the TMR Programme Marie Curie Research Training Grant from the European Commission and a fellowship from the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, respectively.

Address reprint requests to Arthur Zelent, PhD, Leukaemia Research Fund Centre at the Institute of Cancer Research, Chester Beatty Laboratories, 237 Fulham Rd, London SW3 6JB, UK.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.