Abstract

Stem cell factor (SCF) and erythropoietin (Epo) effectively support erythroid cell development in vivo and in vitro. We have studied here an SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cell from cord blood that can be efficiently amplified in liquid culture to large cell numbers in the presence of SCF, Epo, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), dexamethasone, and estrogen. Additionally, by changing the culture conditions and by administration of Epo plus insulin, such progenitor cells effectively undergo terminal differentiation in culture and thereby faithfully recapitulate erythroid cell differentiation in vitro. This SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor is also present in CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells and human bone marrow and can be isolated, amplified, and differentiated in vitro under the same conditions. Thus, highly homogenous populations of SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitors can be obtained in large cell numbers that are most suitable for further biochemical and molecular studies. We demonstrate that such cells express the recently identified adapter protein p62dok that is involved in signaling downstream of the c-kit/SCF receptor. Additionally, cells express the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p21cip1 and p27kip1 that are highly induced when cells differentiate. Thus, the in vitro system described allows the study of molecules and signaling pathways involved in proliferation or differentiation of human erythroid cells.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF mature red blood cells from hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells is tightly controlled by multiple protein factors that are required for both limited growth and terminal differentiation. The two most prominent cytokines that regulate erythropoiesis are erythropoietin (Epo) and stem cell factor (SCF; also referred to as mast cell growth factor [MGF], Steel factor [SLF], or Kit ligand [KL]).1,2 Epo is a 34-kD glycoprotein that promotes survival, proliferation, and differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells in vivo and in vitro.1 SCF, although initially identified by its ability to stimulate proliferation of multipotent hematopoietic progenitor cells, is effective also in supporting growth of already committed progenitors, such as, erythroid and myeloid progenitors, thereby acting synergistically with lineage-restricted cytokines, such as Epo, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF).3-6 Additionally, in more recent studies, the nuclear hormone receptors for dexamethasone and estrogen, glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and estrogen receptor (ER), respectively, have been implicated in causing sustained proliferation of erythroid progenitor cells of chicken in vitro,7-10 whereas the nuclear hormone receptors for thyroid hormone (T3), all-trans retinoic acid (all-trans RA), and 9-cis RA (c-erbA/thyroid hormone receptor [TR], retinoic acid receptor [RAR], and RXR, respectively) were found to promote erythroid differentiation.11-14

Hematopoietic growth factors have been successfully used for selective amplification of a particular subset of hematopoietic progenitor cells in culture. Most of these in vitro experiments use colony assays in semisolid culture media, in some instances followed by short-term liquid culture.3-6 15 In these systems, hematopoietic progenitors will, depending on the specific growth factors added, develop into discrete colonies. However, the number of cells obtained from such colonies that can be further propagated and studied are, in most instances, too low for a more extensive biochemical and functional analysis. Additionally, colony assays are one-step continuous cultures with limited possibilities to manipulate the culture conditions, eg, by addition or withdrawal of specific factors. Furthermore, colony formation is, in most instances, the outcome of a limited number of cell divisions followed by commitment and terminal differentiation. Thus, colony assays normally do not allow study of cell proliferation and differentiation separately as individual genetic programs that determine cell fate. Most of these limitations can be overcome in liquid culture systems that selectively support growth of the cell type wanted and where cells can be induced to differentiate by changing culture conditions.

Previous studies with human erythroid colony-forming cells (ECFC) from peripheral blood established that SCF and Epo, if applied simultaneously, are the most prominent factors required for in vitro growth of erythroid progenitor cells, whereas Epo alone shifts the propensity of progenitor cells towards differentiation.5,6However, so far, the signaling mechanisms of c-kit/SCF receptor and Epo receptor have been studied mainly in established and/or engineered cell lines,16-19 and their analysis in primary human progenitor cells has just commenced.15 One reason is that primary human erythroid progenitors are difficult to obtain as homogenous cell populations in sufficiently high cell numbers to allow more detailed biochemical and molecular studies. In the chicken, homogenous populations of erythroid progenitors can readily be generated in vitro from bone marrow samples that are cultured in the presence of SCF and/or transforming growth factor type α (TGFα) and steroid hormones.7-10,20,21 Furthermore, retroviral vectors have been used to introduce and express in chicken erythroid cells various receptor tyrosine kinases, nuclear hormone receptors, and transcription factors that modulate erythroid cell growth and differentiation.7,21 22

In this study, we describe conditions that allow the selective amplification in liquid culture of SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells from human cord blood, CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells, and bone marrow to large cell numbers that are most suitable for further functional, biochemical, and molecular studies. Under growth conditions, cells express the recently identified adapter protein p62dok that is involved in signaling downstream of c-kit/SCF receptor. We also demonstrate that SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitors can be induced to terminally differentiate in vitro and thereby faithfully recapitulate erythroid differentiation in culture. After induction of differentiation, cells effectively upregulate expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p21cip1 and p27kip1. Thus, in this experimental system, molecules involved in growth control and differentiation of erythroid cells can now be identified and studied, both during normal erythropoiesis and in the pathological state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and cell culture.

Cord blood cells, scheduled for discard and collected according to institutional guidelines, were obtained after normal full-term pregnancies. After placental delivery, the umbilical veins were cannulated and aspirated. Approximately 30 to 40 mL cord blood was routinely recovered and collected in syringes containing 100 U sodium heparin (Novo Nordisk Pharma, Mainz, Germany) per milliliter of cord blood. Residual blood clots were removed by passage through a 70-μm cell strainer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) and light-density, mononuclear cells were isolated using Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation (density 1.077 g/mL; Eurobio, Paris, France). Cells were plated at 4 × 106 cells/mL (days 1 through 3) and later at 2 × 106 cells/mL and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere and high humidity (95%). Partial medium changes were performed daily.

Mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected by apheresis from patients with breast cancer after obtaining informed consent followed by CD34+ selection using a CEPRATE LC34 (CellPro Inc, Bothell, WA) or Isolex 300 device (Baxter Inc, Santa Ana, CA) to enrich CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells, as published.23 24 CD34+ cells (2 to 10 × 106) with 85% to 99% purity were used per experiment and cultured as described above at 2.5 × 106 cells/mL cell density.

The culture medium used was a modification of the growth medium established previously for growth of erythroid progenitors of chicken.9-11,29 25 In brief, culture medium consisted of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; GIBCO-BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom) containing 15% fetal calf serum (FCS; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 1% deionized, delipidated, dialyzed bovine serum albumin (fraction V; Sigma, St Louis, MO), 15% distilled water, 1.9 mmol/L sodium bicarbonate, 0.1 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 0.128 mg/mL iron-saturated human transferrin (Sigma), and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (GIBCO-BRL). Culture medium was supplemented with 1 U/mL recombinant human Epo (rhuEpo; Recormon 1000; 1.2 × 105 U/mg; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 100 ng/mL recombinant human SCF (rhuSCF; Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA), 40 ng/mL long R3 insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1; Sigma), 10−6 mol/L dexamethasone (Sigma), and 10−6 mol/L β-estradiol (Sigma). To monitor cell proliferation, cells were counted daily with an electronic cell counter device (CASY1; Schärfe Systems, Reutlingen, Germany) and cumulative cell numbers were determined. During the initial phase of establishing the culture, cells were subjected to Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation to remove debris and dead cells, if required. Similarly, Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation was used to remove mature and partially mature erythrocytes and dead cells that accumulated during late stages of culture.

To induce differentiation, human erythroid progenitor cells were recovered at day 9 of culture (see above), washed twice with serum-free medium, and seeded at 4 × 106 cells/mL in culture medium containing 1 U/mL rhuEpo and 1 μg/mL recombinant human insulin (rhuIns; Actrapid HM40; Novo Nordisk Pharma). Medium was partially replaced daily by fresh culture medium plus factors. Erythroid differentiation was monitored by measuring cell size (CASY1; Schärfe Systems) and by staining cytospin preparation for hemoglobin (see below). If required, cells of different differentiation stages were purified by Percoll density centrifugation.26

Proliferation assay.

Cell proliferation was assessed quantitatively by measuring the rate of3H-thymidine incorporation. Cells (2 × 104 per well) were incubated in microtiter plates for 48 hours at 37°C in 100 μL culture medium containing various growth factors or combinations thereof or without factor.3H-thymidine (0.75 μCi per well; specific activity, 29 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Buchler, Braunschweig, Germany) was added and cells were incubated for 2 hours. Cells were then lysed by one cycle of freeze/thawing, harvested onto filter plates (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT), and subjected to liquid scintillation counting. Average values of triplicate samples (counts per minute [cpm]) were normalized to 1 × 105 cells seeded.

Colony assay.

Cord blood cells (5 × 104) before culture and 1 × 103 cells at day 6 of culture were plated in 1-mL aliquots in methylcellulose medium on 35-mm plastic culture dishes. Methylcellulose medium contained 0.9% methylcellulose in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM; MethoCult H4100; Stemcell Technologies Inc, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 1% detoxified bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 0.1 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 0.128 mg/mL iron-saturated human transferrin (Sigma), 2 U/mL rhuEpo, 200 ng/mL rhuSCF, 2 × 10−6 mol/L β-estradiol, and 2 × 10−6 mol/L dexamethasone. Cultures were incubated for 14 days in 5% CO2 and high humidity at 37°C. Duplicate plates were analyzed for colonies that contained 30 or more cells using a stereo microscope. Burst-forming units-erythroid (BFU-E) and colony-forming units erythroid (CFU-E) type colonies were evaluated at days 12 through 14. Similarly, colony-forming units granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, macrophage (CFU-GEMM) colonies and colony-forming units macrophage (CFU-M) colonies were identified morphologically and evaluated.

Analysis of hemoglobin content and surface antigen expression.

For analysis of cell morphology and hemoglobin content, cells were cytocentrifuged onto glass slides (700 rpm for 7 minutes; Cytospin 2; Shandon Inc, Pittsburgh, PA) and stained with neutral benzidine and histological dyes, as previously described.27 Photographs were taken with Axiophot II microscope and Kontron ProgRes 3012 CCD camera (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) and processed with Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc, San Jose, CA).

Surface antigen expression of erythroid cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Therefore, cells were preincubated with 1% BSA (fraction V; Sigma) and 1% human IgG (Beriglobin; Behringwerke, Marburg, Germany) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hour and then reacted with specific antibodies (1 hour). Immunophenotyping used monoclonal antibodies to CD3 (anti-LEU-4, clone SK7; Becton Dickinson), CD14 (IOM2, clone RM052; Immunotech, Marseille, France), CD19 (HD37; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), CD29 (MAR4; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), CD34 (anti-HPCA-1, clone My10; Becton Dickinson), CD44 (IM7; Pharmingen), CD49d (9F10; Pharmingen), CD71 (Ber-T9; DAKO), CD117 (YB5.B8; Pharmingen), band 3 (BIII-136; Sigma), and glycophorin A/B (E3; Sigma), followed by reaction with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antimouse IgG (Fc specific; 45 minutes; Sigma). Cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS containing 1% BSA and propidium iodide (2 μg/mL; Sigma) for gating on viable cells. For flow cytometry, a FACScalibur device with CELLQuest software (Becton Dickinson) was used.

Western blotting.

To induce tyrosine phosphorylation of receptors in response to ligand, cells were washed twice with serum-free medium, incubated for 6 hours in culture medium without growth factors, and treated at 37°C for 5 minutes with the following factors: 10 U/mL rhuEpo, 1 μg/mL rhuSCF, 400 ng/mL IGF-I, 200 ng/mL recombinant human interleukin-3 (rhuIL-3; Novartis, Vienna, Austria), 200 ng/mL recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhuEGF; Boehringer Mannheim), 200 ng/mL rhuGM-CSF (Novartis), or 10 μg/mL rhuIns. Cells were harvested and then lysed in 20 μL lysis buffer per 1 × 106 cells (50 mmol/L Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4). Protein lysates were clarified by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 1 minute), and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 10% acrylamide). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (BA85; Schleicher and Schüll, Dässel, Germany) by using a semidry blotting apparatus (Pharmacia LKB, Uppsala, Sweden).

Blocking of membranes and reaction of specific antibodies was performed essentially as described before.28 Briefly, nitrocellulose filters were blocked for 2 hours with blocking buffer (3% BSA, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.05% Tween-20 in Tris-buffered saline [TBS]), rinsed with wash buffer (50 mmol/L Tris HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 mol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20; 10 minutes), and incubated for 1 hour with monoclonal antiphosphotyrosine antibody (4G10; Upstate Biotechnology Inc, Lake Placid, NY). Monoclonal antihuman p21cip1 and antimouse p27kip1 antibodies (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), monoclonal antihuman band 3 antibody (Sigma), or polyclonal rabbit antihuman p62dokantibody29 (kindly provided by N. Carpino, Cold Spring Harbor, NY) were used accordingly. Filters were then washed (50 minutes, wash buffer) and reacted with a horseradish peroxidase-labeled antimouse or antirabbit IgG conjugate (diluted 1:3000; Amersham) in 5% nonfat milk powder in TBS (45 minutes). Filters were washed again (50 minutes, see above), and immunocomplexes were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL reagents; Amersham) and Amersham Hyperfilm ECL films.

RESULTS

In vitro growth of erythroid progenitors from cord blood.

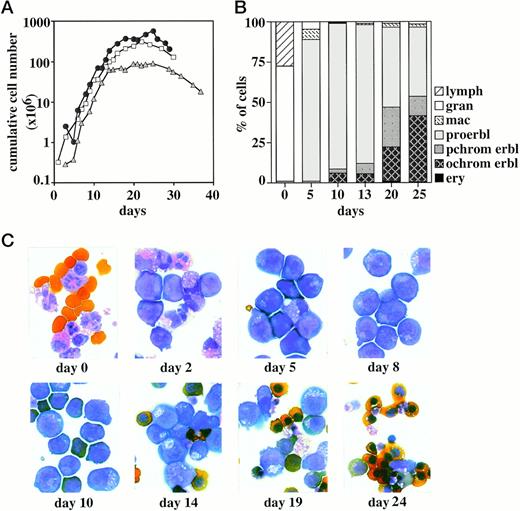

Human erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood were grown in liquid culture in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, dexamethasone, and estrogen using culture conditions modified from growth of chicken red blood cell progenitors.9,10 25 These conditions and the specific factor combination used were also found to be optimal for sustained growth of human erythroid progenitor cells (data not shown). Cells were counted daily and cumulative cell numbers were determined. Figure 1A shows that the specific culture conditions used effectively supported logarithmic growth of erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood until day 15 to 18. This yields a cumulative cell number of 3 to 5 × 108 cells per 10 mL cord blood, corresponding to an overall amplification in cell number of about 500- to 1,000-fold. However, because the starting cell population contains only a minority of erythroid progenitors (<1%, see below), this represents a 105-fold net increase in the number of erythroid progenitor cells within 15 to 18 days of culture. Thereafter, cells ceased proliferation and cell numbers decreased due to an increased rate of spontaneous differentiation and cell death (see below). Thus, the experimental conditions used allow sustained growth of erythroid progenitors to large cell numbers, although their expansion is eventually limited due to a restricted self-renewal capacity and/or lifespan.

Growth kinetics of erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood. (A) Human erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood were grown in liquid culture in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, dexamethasone, and estrogen. Cumulative cell numbers (calculated per 10 mL cord blood) of three representative experiments determined in regular time intervals are shown. (B) Aliquots of the cultures shown in (A) were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine and histological dyes and analyzed for the proportion of proerythroblasts (proerbl), polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (pchrom and ochrom erbl, respectively), erythrocytes (ery), granulocytes (gran), macrophages (mac), and lymphocytes (lymph). The starting cell population (day 0) consisted mainly of granulocytes, monocyte/macrophages, lymphocytes, and some blast-like progenitor cells. Only nucleated cells are evaluated at day 0. (C) Photographs of the cells shown in (A) and (B) after cytocentrifugation and histological staining.

Growth kinetics of erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood. (A) Human erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood were grown in liquid culture in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, dexamethasone, and estrogen. Cumulative cell numbers (calculated per 10 mL cord blood) of three representative experiments determined in regular time intervals are shown. (B) Aliquots of the cultures shown in (A) were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine and histological dyes and analyzed for the proportion of proerythroblasts (proerbl), polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (pchrom and ochrom erbl, respectively), erythrocytes (ery), granulocytes (gran), macrophages (mac), and lymphocytes (lymph). The starting cell population (day 0) consisted mainly of granulocytes, monocyte/macrophages, lymphocytes, and some blast-like progenitor cells. Only nucleated cells are evaluated at day 0. (C) Photographs of the cells shown in (A) and (B) after cytocentrifugation and histological staining.

The growth potential of erythroid progenitors from cord blood was also assessed in colony assays. Therefore, cells were seeded either at the day of isolation or after 6 days of liquid culture (see above) in semisolid methylcellulose medium supplemented with SCF, Epo, and steroid hormones. Two weeks later, the number of colonies representing different stages of differentiation and lineage commitment were determined. In this assay, the starting cell population yielded 3 × 102 BFU-E and CFU-E type colonies per 105 cells seeded and about 50 CFU-M and CFU-GEMM type colonies. Most importantly, when cells were grown in liquid culture for 6 days and then seeded in colony assays, the number of erythroid colonies that developed had increased by 100-fold (3 × 102 BFU-E and CFU-E type colonies per 103 cells seeded) and only very few nonerythroid colonies were observed (<3%). This finding demonstrates that the specific conditions used for liquid culture effectively supported the outgrowth of cells with a differentiation capacity confined to the erythroid lineage.

To further extend this conclusion, cells were analyzed by morphological criteria using cytospin preparations stained with neutral benzidine and histological dyes. Cord blood samples (which were depleted from erythrocytes by Ficoll purification) consisted mainly of granulocytes, monocyte/macrophages, lymphocytes, and some blast-like cells (Fig 1B and C). Mature erythrocytes, which were not efficiently removed during Ficoll purification, and a low number of polychromatic erythroblasts (2% to 3%) were also present. This picture changed dramatically after 5 to 8 days of culture in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, and steroid hormones. Proerythroblast-like progenitors clearly represented the major cell population with some residual macrophages and granulocytes (Fig 1B and C). At days 9 to 13 of culture, the cell population was completely erythroid, comprising 86% to 92% of proerythroblasts and some polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (3% to 7% and 5% to 7%, respectively; Fig 1B). With prolonged time in culture, the rate of spontaneous differentiation further increased, and at day 20 the cell population consisted of approximately 45% polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts; at day 25, 1% to 2% mature enucleated erythrocytes were found.

The outgrowth of erythroid progenitors was also monitored by assessing expression of specific cell surface proteins by flow cytometry. At day 9 of culture, cells effectively expressed, as expected, c-kit/SCF receptor (CD117), high levels of transferrin receptor (CD71), and low levels of glycophorin A/B and band 3 (Fig2). Cells also expressed high levels of the adhesion molecules α4β1 integrin VLA-4 (CD29, CD49d) and CD44; no expression of T- and B-cell–specific and myeloid markers (CD3, CD19, and CD14, respectively) was detected (data not shown). Thus, at this point in time, the culture represented a homogenous population of erythroid cells. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that all cells can be effectively induced to undergo erythroid differentiation (see below).

Cell surface expression profile of erythroid progenitor cells. Erythroid progenitor cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of c-kit/SCF receptor (CD117), transferrin receptor (CD71), glycophorin A/B, and band 3 as indicated (grey). Control cells were incubated with FITC-labeled secondary antibody only (white). Cells at day 9 of culture are shown.

Cell surface expression profile of erythroid progenitor cells. Erythroid progenitor cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of c-kit/SCF receptor (CD117), transferrin receptor (CD71), glycophorin A/B, and band 3 as indicated (grey). Control cells were incubated with FITC-labeled secondary antibody only (white). Cells at day 9 of culture are shown.

Growth factor dependence of erythroid progenitor cells.

We next wanted to assess the individual contribution of Epo, SCF, and IGF-1 for growth of erythroid progenitor cells (1) by determining receptor phosphorylation in response to specific growth factors and (2) by measuring the rate of DNA synthesis induced by factor. Therefore, cells were incubated without factor for 6 hours; Epo, SCF, or IGF-1 were added; and 5 minutes later, cell lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis using a phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody. After the addition of Epo, tyrosine phosphorylation of the 78-kD Epo receptor was clearly evident (Fig 3A). Epo also induced tyrosine phosphorylation of several other proteins, probably Jak2, Stat5, Shc, and syp, which is in line with previous studies.15,17,18,30,31 Phosphorylation of these proteins was clearly specific for Epo and not seen for control cells. As expected, SCF effectively induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the p145 c-kit/SCF receptor15 together with phosphorylation of a faster migrating protein. Stripping and reprobing of the Western blot with receptor specific antisera demonstrated that the 78-kD and 145-kD tyrosine phosphorylated bands correspond to Epo receptor and c-kit/SCF receptor, respectively (data not shown). Additionally, IGF-1 and insulin led to tyrosine phosphorylation of the IGF-1 and insulin receptor β-chains, demonstrating that these cells express IGF-1 and insulin receptors. No change in tyrosine phosphorylation was obtained with, eg GM-CSF, IL-3, and EGF. Thus, the erythroid progenitors obtained expressed receptors for Epo, SCF, IGF-1, and insulin but lacked detectable levels of receptors for, eg, GM-CSF, IL-3, and EGF.

Erythroid progenitor cells respond to Epo, SCF, IGF-1, and insulin. (A) Erythroid progenitor cells were analyzed for specific responses to Epo, SCF, GM-CSF, IGF-1, insulin, IL-3, and EGF by Western blotting and staining with phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody (4G10). One hundred micrograms of protein lysate per lane. Control, no factor added. Cells at day 9 of culture are shown. (B)3H-thymidine incorporation in response to factor of the same cell preparation shown in (A). Factors were applied individually or in various combinations as indicated. 3H-thymidine incorporation was determined 48 hours after the addition of factors; for details see Materials and Methods.

Erythroid progenitor cells respond to Epo, SCF, IGF-1, and insulin. (A) Erythroid progenitor cells were analyzed for specific responses to Epo, SCF, GM-CSF, IGF-1, insulin, IL-3, and EGF by Western blotting and staining with phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody (4G10). One hundred micrograms of protein lysate per lane. Control, no factor added. Cells at day 9 of culture are shown. (B)3H-thymidine incorporation in response to factor of the same cell preparation shown in (A). Factors were applied individually or in various combinations as indicated. 3H-thymidine incorporation was determined 48 hours after the addition of factors; for details see Materials and Methods.

To assess the effect of Epo, SCF, IGF-1, and insulin on progenitor cell growth quantitatively, the rate of DNA synthesis in response to factor was measured. Factors were added either individually or in combinations thereof; 48 hours later, cells were assayed for their proliferative response in 3H-thymidine incorporation assays. When individual factors were applied, Epo and SCF were found to be the most effective (Fig 3B). Furthermore, if applied simultaneously, the effect of Epo and SCF was more than additive, indicating that both factors synergized in inducing DNA synthesis in these cells. Administration of dexamethasone and estrogen did not significantly augment3H-thymidine incorporation, at least under the experimental conditions used (FCS was not depleted from endogenous steroids). The activity of IGF-1 and insulin on 3H-thymidine incorporation was also very low (Fig 3 and data not shown). Most likely, the effects of steroids, IGF-1, and insulin are more pronounced under serum-free conditions. However, both IGF-1 and steroid hormones (which were not effective individually) enhanced the rate of DNA synthesis induced by Epo plus SCF and there was no further increase by the addition of other factors such as, EGF, IL-3, and GM-CSF, which is in line with the Western blotting data.

In conclusion, SCF and Epo, if added simultaneously, clearly represent the most potent factors required for inducing proliferation of this type of erythroid progenitor cell. To ensure optimal growth rates, the addition of IGF-1 was also important. However, we emphasize that an efficient outgrowth of erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood samples was critically dependent on the administration of dexamethasone and, to a lesser extent, of estrogen, which significantly reduced the rate of spontaneous differentiation (B.P., P.B. and M.Z., data not shown).

Erythroid progenitor cells differentiate into mature erythrocytes in vitro.

Next, we determined whether the erythroid progenitor cells obtained were capable of differentiating in vitro into fully mature enucleated erythrocytes. Cells were withdrawn from growth factors and incubated in the presence of Epo and insulin using culture conditions modified from in vitro differentiation of red blood cell progenitors of chicken.9-11 25 After the induction of differentiation, cells began to accumulate hemoglobin and gradually acquired the morphology of normal erythrocytes while undergoing 2 to 3 cell divisions followed by cell cycle arrest (Figs 4 and5A and data not shown). Parallel to the onset of differentiation, a decrease in cell size was routinely observed (Fig 5B). At day 3 of differentiation, orthochromatic erythroblasts represented the majority of the cell population (Figs 4and 5A). The proportion of orthochromatic erythroblasts further increased to 72% at day 4; at this time, fully mature enucleated erythrocytes constituted about 9% of the culture. As expected, cells kept as an experimental control under growth conditions (SCF, Epo, IGF-1, and steroid hormones; see above) did not differentiate (data not shown). This demonstrates that, with the specific culture conditions used, the erythroid progenitor cells obtained were fully competent in differentiating terminally.

Erythroid progenitor cells differentiate in vitro. Erythroid progenitor cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of Epo and insulin (see Materials and Methods). After 1, 2, 4, and 5 days of differentiation, cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine and histological dyes and photographed. Day 0, undifferentiated cells cultured under standard growth conditions. Please note the enucleated cells obtained at day 4 to 5 of differentiation.

Erythroid progenitor cells differentiate in vitro. Erythroid progenitor cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of Epo and insulin (see Materials and Methods). After 1, 2, 4, and 5 days of differentiation, cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine and histological dyes and photographed. Day 0, undifferentiated cells cultured under standard growth conditions. Please note the enucleated cells obtained at day 4 to 5 of differentiation.

Kinetics of in vitro differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells. (A) Aliquots of the cultures shown in Fig 4 were evaluated for the proportion of proerythroblasts (proerbl), polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (pchrom and ochrom erbl, respectively), and erythrocytes (ery). (B) Cell size profile of the same cells as shown in (A) demonstrate reduction in cell size during differentiation: undifferentiated cells, white; differentiated cells at 24, 48, and 72 hours, grey, dark grey, and black, respectively.

Kinetics of in vitro differentiation of erythroid progenitor cells. (A) Aliquots of the cultures shown in Fig 4 were evaluated for the proportion of proerythroblasts (proerbl), polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (pchrom and ochrom erbl, respectively), and erythrocytes (ery). (B) Cell size profile of the same cells as shown in (A) demonstrate reduction in cell size during differentiation: undifferentiated cells, white; differentiated cells at 24, 48, and 72 hours, grey, dark grey, and black, respectively.

Interestingly, the starting cell preparation (day 9 of culture) apparently contained two populations of erythroid progenitor cells that differentiated with different kinetics. The majority of cells were proerythroblasts, whereas a subpopulation of cells had presumably already further advanced in maturation and exhibited morphological characteristics of polychromatic cells. These cells differentiated with faster kinetics and gave rise to orthochromatic erythroblasts by day 2 of differentiation. Differentiation of two apparently different progenitor cell populations is also seen in the specific changes observed in cell size (Fig 5B). However, we emphasize that eventually all SCF/Epo-dependent progenitor cells differentiate into orthochromatic erythroblasts and enucleated erythrocytes, indicating that the culture conditions used effectively support normal erythroid cell maturation in vitro.

Growth and differentiation in vitro of erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells and bone marrow.

Next, we determined whether CD34+ peripheral blood stem cell preparations contain erythroid progenitor cells that behave similarly to the erythroid progenitors from cord blood and can be amplified and differentiated in vitro accordingly. Therefore, CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells were obtained by immunomagnetic bead affinity purification of leukapheresis preparations and cultured in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, and steroid hormones using the growth conditions described above. Cells were counted daily and cumulative cell numbers were determined. Under such culture conditions, erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells exhibited similar growth kinetics as the erythroid progenitors derived from cord blood (data not shown). The outgrowth of progenitor cells started at day 4 of culture, accompanied by an increase in cell size (from 8.5 to 11 μm; data not shown). Cumulative cell numbers increased until day 17, whereas in the following days, cells stopped proliferating and cell numbers decreased.

Cells were also analyzed by morphology after cytospin centrifugation and staining with histological dyes. At day 6 of culture, the cell population comprised 88% proerythroblasts expressing high levels of CD71/transferrin receptor (Fig 6A and B and data not shown); some persisting granulocytes and macrophages were also present. The culture was almost exclusively erythroid at day 9 to 10. At later stages, cells started to spontaneously differentiate (day 13 to 15), and an increasing number of polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts was found. The number of orthochromatic erythroblasts further increased with time, and at days 21 and 25 of culture, represented 52% and 62%, respectively, of the cell population. At this time, the culture also contained some terminally differentiated fully mature enucleated erythrocytes.

In vitro growth and differentiation of erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells. (A) Erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells (starting cell population, day 0) were grown in liquid culture in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, dexamethasone, and estrogen. At days 4, 9, and 14 of culture, cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine plus histological dyes. (B) Cultures of erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells shown in (A) were analyzed for proportion of proerythroblasts (proerbl), polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (pchrom and ochrom erbl, respectively), erythrocytes (ery), granulocytes (gran), macrophages (mac), and lymphocytes (lymph). The starting cell population (day 0) consisted mainly of small progenitor cells (striped box) and some granulocytes and macrophages as indicated. At day 0, only nucleated cells are evaluated. (C) Erythroid progenitor cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of Epo and insulin (see Materials and Methods). After 2, 3, 4, and 5 days of differentiation, cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine and histological dyes and evaluated for the proportion of proerythroblasts, polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts, and erythrocytes as in (B).

In vitro growth and differentiation of erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells. (A) Erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells (starting cell population, day 0) were grown in liquid culture in the presence of SCF, Epo, IGF-1, dexamethasone, and estrogen. At days 4, 9, and 14 of culture, cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine plus histological dyes. (B) Cultures of erythroid progenitors from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells shown in (A) were analyzed for proportion of proerythroblasts (proerbl), polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts (pchrom and ochrom erbl, respectively), erythrocytes (ery), granulocytes (gran), macrophages (mac), and lymphocytes (lymph). The starting cell population (day 0) consisted mainly of small progenitor cells (striped box) and some granulocytes and macrophages as indicated. At day 0, only nucleated cells are evaluated. (C) Erythroid progenitor cells were induced to differentiate in the presence of Epo and insulin (see Materials and Methods). After 2, 3, 4, and 5 days of differentiation, cells were subjected to cytocentrifugation and staining with neutral benzidine and histological dyes and evaluated for the proportion of proerythroblasts, polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts, and erythrocytes as in (B).

Western blot analysis with a phosphotyrosine-specific monoclonal antibody demonstrated that erythroid progenitors from CD34+stem cell preparations express c-Kit/SCF receptor, Epo receptor, IGF-1 receptor, and insulin receptor, which were effectively phosphorylated in response to ligand (data not shown). GM-CSF, IL-3, EGF, and TGFα were without effect. Thus, the erythroid progenitors obtained from CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells behaved similarly to those isolated from cord blood: they exhibit similar growth kinetics and expressed receptors for SCF, Epo, IGF-1, and insulin.

Additionally, these progenitors were fully competent in undergoing terminal differentiation in response to Epo and insulin (Fig 6C). At day 3, the culture exhibited 55% and 10% polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts, respectively, and 2% mature erythrocytes. By day 5 of differentiation, the number of orthochromatic erythroblasts and erythrocytes had further increased. At this stage, the number of fully mature enucleated erythrocytes was found consistently to be higher than that observed for differentiation of erythroid progenitors from cord blood, suggesting that terminal differentiation in vitro of red blood progenitors from CD34+ stem cells is more efficient.

In summary, the SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitors present in CD34+ peripheral blood stem cell preparations behaved very similarly to the respective progenitor cells obtained from cord blood. Additionally, SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells were also isolated from human bone marrow preparations, amplified, and differentiated in vitro accordingly (data not shown).

p62dok and CDK inhibitor p21cip1 and p27kip1 expression in erythroid cells.

Because the experimental system described above allows selective programming of erythroid progenitor cells to either self-renewal or terminal differentiation, we thought to determine the expression pattern of signaling molecules in such cells that have been implicated in either process. To this end, we investigated expression of p62dok, a recently identified adapter protein involved in signal transduction downstream of receptor and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases such as, c-kit/SCF receptor, bcr-abl, and v-abl.29,32 Cells of different differentiation stages were prepared and analyzed for p62dok expression in Northern and Western blots using p62dok-specific probe and antibody (kindly provided by J. Grimm and W. Birchmeier [MDC, Berlin, Germany] and N. Carpino [Cold Spring Harbor, NY], respectively). We demonstrate that proliferating SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells express p62dok mRNA and protein (Fig 7 and data not shown). Most importantly, p62dok expression declines when cells differentiate. Additionally, c-kit/SCF receptor expression also decreases upon differentiation, which is in line with previous studies on SCF-dependent erythroid progenitors of chicken20 (data not shown). As expected, expression of the anion transporter band 3, used as an experimental control, was effectively upregulated during differentiation (Fig 7).

p62dok, p21cip1, and p27kip1 expression in proliferating and differentiating erythroid cells. SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells at different stages of differentiation were analyzed for p62dok, p21cip1, and p27kip1expression by Western blotting. Band 3 expression is shown to demonstrate efficient differentiation. Lane 1, undifferentiated progenitor cells at day 9 of culture. Lanes 2 through 4, differentiated cells at day 3 of differentiation following fractionation by Percoll density centrifugation. Samples were normalized for equal protein loading per lane (30 μg). The proportion of proerythroblasts, polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts, and erythrocytes is indicated.

p62dok, p21cip1, and p27kip1 expression in proliferating and differentiating erythroid cells. SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells at different stages of differentiation were analyzed for p62dok, p21cip1, and p27kip1expression by Western blotting. Band 3 expression is shown to demonstrate efficient differentiation. Lane 1, undifferentiated progenitor cells at day 9 of culture. Lanes 2 through 4, differentiated cells at day 3 of differentiation following fractionation by Percoll density centrifugation. Samples were normalized for equal protein loading per lane (30 μg). The proportion of proerythroblasts, polychromatic and orthochromatic erythroblasts, and erythrocytes is indicated.

Preliminary experiments suggested that the CDK inhibitor p27kip1 is regulated during differentiation of erythroid progenitors from chicken (P.B. and M.Z., unpublished data). Thereupon, we analyzed p27kip1expression in proliferating SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitors and differentiated cells. Figure 7 shows that p27kip1 protein level dramatically increases when cells differentiate. Additionally, expression of p21cip1, another member of the same CDK inhibitor family, was also induced.

In summary, we demonstrate that SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells from cord blood express the adapter protein p62dokand the CDK inhibitors p21cip1 and p27kip1; these molecules have been implicated in self-renewal and cell cycle arrest, respectively, and undergo specific changes in expression when cells differentiate. Thus, the experimental system described in this report readily allows the analysis of molecules involved in growth and differentiation of primary human erythroid progenitor cells.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe an SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor that is efficiently obtained from cord blood, CD34+peripheral blood stem cells, and bone marrow by using specific culture conditions and SCF, Epo, IGF-1, and steroid hormones (dexamethasone and estrogen). This progenitor can be selectively amplified in liquid culture to large cell numbers (3 to 5 × 108 cells/10 mL cord blood). Whereas the starting cell preparations contain only a minor population of erythroid progenitors (<1%, as determined in colony assays), there was a 105-fold net amplification in cell number within 15 to 18 days of culture. Additionally, the progenitor cells obtained were fully competent of differentiating terminally into erythrocytes in response to differentiation factors (Epo, insulin). Thus, the experimental system described allows the selective amplification of an erythroid progenitor in liquid culture to homogenous cell populations and high cell numbers that allow a more detailed biochemical, molecular, and functional analysis. We demonstrate that this progenitor is critically dependent on SCF and Epo for efficient growth in vitro and, therefore, refer to this cell as SCF/Epo-dependent progenitor. IGF-1 appears not to be a crucial growth factor (at least in the presence of SCF, Epo, and serum) but, if added, does further improve the growth conditions. Additionally, efficient outgrowth of SCF/Epo-dependent progenitors critically required dexamethasone presumably by inhibiting spontaneous differentiation.10 Culture conditions that additionally contained estrogen further enhanced progenitor cell outgrowth (B.P., P.B., and M.Z., unpublished data). Notably, the SCF/Epo-dependent progenitor described in this study exhibits properties very similar to an SCF-dependent erythroid progenitor obtained from the bone marrow of chicken.10,20 This progenitor can be effectively amplified in the presence of chicken SCF, chicken serum, and steroid hormones without exogenous Epo (Epo is so far not cloned for chicken). Thus, although the human progenitor studied in this report requires both SCF and Epo for efficient growth in culture, the erythroid progenitor of chicken appears to be solely dependent on SCF and factors in chicken serum. However, these progenitors are different from a TGFα-dependent erythroid progenitor obtained from chicken bone marrow in the presence of TGFα (and steroid hormones) which exhibits a considerably longer lifespan in vitro.8,9 20 As demonstrated above, the human SCF/Epo-dependent progenitor studied here did not express detectable levels of TGFα/EGF receptor and did not respond to the addition of TGFα and/or EGF.

The growth conditions employed for amplification of the SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor described in this paper are a modification of those used for propagation of primary nontransformed or oncogene-transformed erythroid cells from chicken bone marrow9,10 25; various chicken specific components were substituted by the respective mammalian factors. Cells are first amplified under particular medium conditions in the presence of a specific combination of factors that support cell proliferation (SCF, Epo, IGF-1, and steroid hormones); changing the culture conditions by replacing the growth promoting agents with appropriate differentiation factors (Epo, insulin) induces their maturation and differentiated orthochromatic erythroblasts and enucleated erythrocytes are obtained. Differentiation was most effective when cells showed optimal growth rates (day 8 to 10 of culture). Thus, the specific culture conditions used direct the cells to either proliferation or differentiation.

The culture conditions used are different from the two-step culture system by Fibach et al.33,34 This system involves a first, Epo-independent phase in which early erythroid progenitors (eg, BFU-E cells) proliferate and differentiate into CFU-E type progenitors. In a second phase, cells are cultured in the presence of Epo and continue to proliferate and to mature into orthochromatic erythroblasts and enucleated erythrocytes. Although in such cultures high numbers of largely pure erythroid cells can be obtained, the system does not separate cell proliferation and terminal differentiation and thus does not allow study of self-renewal and differentiation of erythroid cells individually. This is clearly the advantage of the system described in this report, because, by choosing the appropriate media conditions plus factors, proliferating cells can be reprogrammed and directed to differentiation. The culture conditions used in this report are also different from the ones used by Krystal et al35 and Taniguchi et al,36 which have, eg, insulin in growth medium, whereas here insulin is used to induce differentiation. The presence of insulin in the growth medium used in our study led to an increased rate of differentiation, delayed growth kinetics, and a lower overall cell number than control (data not shown). However, we emphasize that the effect of insulin might be different, for example, under serum free conditions such as those used by Krystal et al.35

It will now be interesting to identify on a molecular level the determinants that are important in controlling growth and differentiation of the erythroid progenitor cell described in this report. As a first step, we have measured receptor phosphorylation for SCF receptor, Epo receptor, IGF-1 receptor, and insulin receptor in response to ligand. Additionally, we provide first evidence that such progenitor cells express p62dok mRNA and protein. p62dok represents a recently identified adapter molecule that associates with p120 ras GTPase-activating protein (GAP) and that is rapidly tyrosine phosphorylated upon activation of c-kit/SCF receptor.29 32 Association of p62dok with GAP correlates with tyrosine phosphorylation, indicating that p62dok is a component of a signal transduction pathway downstream of the c-kit/SCF receptor. Furthermore, both SCF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of p62dok and its constitutive tyrosine phosphorylation in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cells correlate with cell proliferation, strongly supporting the view that p62dok is an important molecule in mitogenic signaling. Interestingly, as shown in this report, SCF/Epo-dependent erythroid progenitor cells express p62dok and its expression declines when cells cease proliferation and undergo terminal differentiation into mature red blood cells. Thus, in these progenitor cells, p62dok might be involved in signaling that induces cell proliferation.

After induction of differentiation, SCF/Epo-dependent progenitor cells, as demonstrated above, effectively upregulate the CDK inhibitors p21cip1 and p27kip1 and undergo cell cycle arrest. This finding is reminiscent of the increase of p21cip1 and p27kip1, eg, during oligodendrocyte differentiation.37,38 Cellular differentiation is associated with a reduction in overall G1 CDK activity, which is, eg, regulated through specific interactions of CDKs with CDK inhibitors.39 p21cip1 and p27kip1are members of the same family of CDK inhibitors and their upregulation during erythroid cell differentiation might affect G1 CDK activity and therefore influence the propensity of erythroid progenitor cells to undergo either cell cycle reentry or growth arrest. The specific signals that induce p21cip1 and p27kip1 in differentiating erythroid cells still remain elusive. Furthermore, in erythroid progenitor cells of chicken differentiation induction causes downregulation of D-type cyclins and CDK4,40 indicating that reprogramming of erythroid cell gene expression during differentiation involves multiple components of the cell cycle machinery. All of these findings provide further support for the existence of two distinct genetic programs that determine erythroid cell proliferation and differentiation, respectively. Information about the molecular determinants and how they function in controlling cell growth and differentiation cannot be reliably obtained from studies in established cell lines that exhibit aberrantly altered properties due to their transformed and/or immortalized phenotype. The primary culture system described in this report is particularly well suited for studying such signaling molecules and how they operate, both during normal erythropoiesis and in the pathological state.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are most grateful to Amgen Inc for providing recombinant human SCF and to Novartis Ltd for recombinant human IL-3 and GM-CSF. Additionally, we thank J. Grimm and W. Birchmeier for p62dok-specific probe, N. Carpino for anti-p62dok antibody, I. Körner for CD34+peripheral blood stem cell purification, G. Blendinger and R. Franke for tissue culture work, and I. Gallagher for typing the manuscript. We are also most grateful to B. Dörken for continuous support.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Martin Zenke, PhD, Max-Delbrück-Center for Molecular Medicine, MDC, Robert-Rössle-Str. 10, D-13122 Berlin, Germany; e-mail:zenke@mdc-berlin.de.