Abstract

The influence of ligand:receptor affinity on B-cell antigen receptor (BCR)-induced apoptosis in the IgM+ Burkitt lymphoma line, Ramos, was evaluated with a group of affinity-diverse murine monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) specific for human B-cell IgM. The studies showed not only a minimal affinity threshold for the induction of apoptosis, but, interestingly, also a maximal affinity threshold above which increases in affinity were associated with diminished apoptosis. The lesser capacity of high-affinity MoAb to induce apoptosis was paralleled by a lesser capacity to induce receptor cross-linking. At high ligand concentration, high MoAb affinity was also associated with a diminished capacity to induce early protein tyrosine phosphorylation. The compromised capacity of two high-affinity MoAbs to trigger apoptosis may be, at least in part, explained by two separate phenomena that can impair the formation of mIgM cross-links: (1) more stable univalent binding and (2) a tendency for monogamous binding of both MoAb Fab to two Fab epitopes on mIgM. These in vitro studies suggest that the use of the highest affinity MoAbs for antireceptor immunotherapies that depend on receptor cross-linking might, on occasion, be contraindicated.

IN ADDITION TO serving as a transducer of signals for clonal proliferation, the membrane Ig (mIg) receptor complex on B cells can, when cross-linked, initiate signals that lead to growth inhibition and apoptosis. The biochemical explanation for these diverse functional effects is only beginning to be understood. Although the signal transducing pathways for both proliferation and apoptosis involve early protein tyrosine phosphorylation and upregulation of intracellular Ca2+,1-5 the pathway for apoptosis results in the activation of cysteine proteases characteristic of programmed cell death.6 Studies with normal untransformed B lymphocytes have shown that immature B cells are more susceptible to apoptosis than are mature B lymphocytes given the same degree of mIg engagement by antigen or surrogate antigen, ie, anti-Ig antibody (Ab).7 However, mature B lymphocytes are not refractory to induction of apoptosis via the mIg signaling pathway and can be induced to programmed cell death upon very extensive receptor cross-linking.8-10 Importantly, transformed B-lymphocyte clones are also susceptible to growth regulation after signal transduction through the antigen receptor complex. Evidence in support of Ag-mediated positive selection during the clonal expansion of B-cell malignancies is fairly abundant,11-15 and primary cultures of certain malignant B cells can proliferate in response to mIg cross-linking.16,17 Conversely, transformed B cells can also receive signals for growth cessation and apoptosis upon culture with mIg cross-linking ligands.3-6,10,16,18 Certain malignant B-cell populations have been described that respond either positively or negatively depending upon the apparent degree of receptor cross-linking and the presence or absence of cytokines.16 17

The above-described and other19-28 evidence strongly suggest that the qualitative response of both B and T lymphocytes to antigen engagement is influenced by the quantitative amount of signal. Importantly, the quantitative amount of signal is strongly influenced by the interrelationship between mIg:Ag affinity, Ag concentration, Ag valency, and mIg density.19-29 These factors must be taken into consideration in determining whether a given mIg-binding ligand might be useful in therapies designed to negatively regulate malignant B-cell growth.

In the present study, we use a series of well-characterized antihuman IgM monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) of known binding site specificity and known binding site affinity30 to explore how a ligand’s affinity for mIg might influence the induction of apoptosis in the human Burkitt lymphoma B-cell line, Ramos. This cell line has been previously shown to be triggered into apoptosis upon cross-linking of its mIgM receptors.10 31 Interestingly, the study shows that, above an upper threshold, an increase in ligand:receptor affinity diminishes the potential for triggering apoptosis. Evidence is presented in support of two mechanisms that may contribute to this phenomenon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

The IgM+, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative Burkitt lymphoma B-cell line, Ramos,32 was kindly provided by Dr Vince Tsiagbe (New York University Medical Center, New York, NY) and was maintained in RPMI-1640 + 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) + 20 mmol/L HEPES + 2 mmol/L glutamine + 5 × 10−5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol.

Murine antihuman IgM MoAb and anti-IgM:dextran conjugates.

Previous reports have described the derivation, epitope specificity, and intrinsic Fab′ affinity of the seven anti-IgM MoAbs used in the present study.30,33 MoAbs with specificity for the Cμ1, Cμ2, and Cμ4 domains of IgM are represented. Fab′ fragments of each MoAb have been shown to bind two identical epitopes per mIgM molecule.30 The MoAb that we have designated HB57 in this and previous studies30,33 is of the same clonal origin as MoAb DA4.4 used in other studies10 (American Type Culture Collection, Bethesda, MD). All MoAbs are of murine IgG1 isotype and were purified from hybridoma ascitic fluid by Affigel Protein-A-column chromatography (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). MOPC-21 was used as an isotype control for the anti-IgM MoAbs. The preparations of MoAb:dextran conjugates used in this study have also been described previously and contained either 15-21 anti-IgM MoAb per dextran20 or 10-12 anti-IgM MoAb plus a similar number of B-cell nonspecific MoAb (UPC-10) covalently conjugated to each high molecular weight (MW) dextran molecule.34 In the latter case, UPC-10 had been cocoupled to the dextran as an isotype control for another cocoupled B-cell–specific MoAb tested in the previous study.34 The anti-IgM MoAbs coupled to dextran were all specific for the same or proximal epitope on the Cμ2 domain of human mIgM, but bound with varying intrinsic affinities, ie, MoAb HB57 (Ka = 5 × 108 mol/L−1), MoAb Mu53 (Ka = 2 × 107 mol/L−1), and MoAb P24 (Ka = 2 × 106mol/L−1).30 33

Cell culture conditions and assays for apoptosis.

Ramos cells were cultured in triplicate microtiter wells at 105 cells per 200 μL in culture medium containing various concentrations of anti-IgM MoAb or anti-IgM:dextran conjugate. Apoptosis was assessed by staining with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-annexin and flow cytometric analysis (Becton Dickinson FACScan; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) as described elsewhere35 (Apoptosis Detection Kit from R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Positive staining with FITC-annexin reflects a shift of phosphatidyl serine from the inner to the outer layer of the cytoplasmic membrane that occurs early in apoptosis.35 In an assay in which four identical replicates of control cultures or anti-IgM–treated apoptotic cultures were evaluated for the percentage of annexin-positive cells and mean fluorescence intensity of FITC-annexin binding, we observed minimal intraexperimental variability, ie, standard deviation (SD) values were less than 6% of the mean values. In some experiments, apoptotic cells were monitored for nuclear fragmentation by staining overnight (ON) with a hypotonic propidium iodide (PI) solution and subsequent flow cytometric analysis to detect nuclei with hypodiploid levels of DNA, as described by Nicoletti et al.36

Culture conditions for protein tyrosine phosphorylation and preparation of lysates.

For measurements of protein tyrosine phosphorylation, Ramos cells were washed in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) + 20 mmol/L HEPES, equilibrated in this serum-free medium at 37°C for 30 minutes, and incubated at 4 × 106 cells per 2 mL with the indicated concentrations of bivalent anti-IgM MoAb or anti-IgM:dextran for 1 or 5 minutes. After the appropriate culture interval, 8 mL of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) + 1 mmol/L Na3VO4 were added and the cells were spun at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes. After one additional wash with 8 mL of the same buffer, the cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS + 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, transferred into prechilled microfuge tubes, and spun at 14,000 rpm for 10 seconds. The pellets were resuspended in 100 μL of ice-cold 1× lysis buffer (20 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 8, 10% vol/vol glycerol, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L Na3VO4, 1% Triton X-100, 1% aprotinin, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.06 mg/mL ovomucoid trypsin inhibitor, 0.3 mmol/L TLCK, 20 μmol/L leupeptin). After 10 minutes of incubation on ice, the lysates were spun at 14,000 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes and the supernatants were transferred into prechilled microtubes. Two 10-μL aliquots were removed for a BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and the remainder of each lysate was stored at −70°C until further use.

Analysis of lysates for tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins.

Lysates (5 to 20 μg protein per lane, depending on the experiment; identical loading of samples within an experiment) were electrophoretically separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions for 2 hours (200 V) on minislab 10% acrylamide gels, together with prestained MW markers (Sigma #1677; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and a positive control for tyrosine phosphorylated proteins (1:20 dilution of an epidermal growth factor-stimulated cell lysate [gift of J. Schlessinger Laboratory, New York University Medical Center] that had been aliquoted and frozen at −70°C). After electrophoresis, the separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose. A blocking step was performed at room temperature (RT) for 20 minutes with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in washing buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-Cl, pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20), and the blots were then incubated for 40 minutes at RT on a rocker with a 1:5,000 dilution of horseradish-peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated recombinant anti-P(tyr) RC20H (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, NY) before washing and reincubation with ECL reagents purchased from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL). ECL detection was on autoradiographic film (Dupont NEF-496; Dupont, Wilmington, DE).

As a check for the amount of protein loaded per lane, blots were reprobed with a 1:10,000 dilution of rabbit anticatalase (kind gift of Dr Paul Lazarow, Mt Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY)37 in blocking buffer (5% milk [Bio-Rad] in washing buffer) after the following steps: (1) a stripping procedure that involved incubation of the dry nitrocellulose blot, while rocking, with washing buffer adjusted to pH 2.3 for 10 minutes at RT; (2) 4 quick (∼5 seconds) washes with a large volume of washing buffer at normal pH 7.5; and (2) a 20-minute blocking step with 5% milk in washing buffer. The bound rabbit anticatalase was detected, after washing steps (4 quick washes plus 4 additional 5-minute washes while rocking), by the addition of a 1:5,000 dilution of HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit Ab (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) and ECL as described above.

The densitometric intensity of P(tyr) bands and catalase bands on autoradiographic film was quantitated by a Molecular Dynamics (Sunnyvale, CA) scanning densitometer and associated Molecular Dynamics ImageQuaNT software. For each blot, band volume measurements for anti-P(tyr) intensity were corrected by a protein loading adjustment factor. The protein adjustment factor was determined by quantitating the densitometric intensity (volume) of each catalase band in the various lanes of the stripped and reprobed blot. The lane with the lowest densitometric intensity of catalase was given an adjustment factor value of 1. The adjustment factor values for other lanes were determined by dividing the densitometric intensity of the catalase band in each of the other lanes in a given blot by the densitometric intensity of the catalase band in the lane with the lowest intensity. Division of the intensity values for P(tyr) proteins in each lane by that lane’s protein adjustment factor compensated for variations in the loading of protein between lanes. (The mean ± SD of the adjustment factors calculated for the various reported lanes was 1.9 ± 1.0.) The corrected P(tyr) intensity value for each protein in lysates from control (MOPC-21–incubated) cells was then subtracted from the corrected P(tyr) intensity value for the respective protein in lysates from anti-IgM–stimulated B cells to give Δ values for anti-IgM–stimulated protein tyrosine phosphorylation of each protein band. Finally, the Δ values were expressed as a percentage of the maximum Δ values observed for that protein under the conditions of high-, intermediate-, or low-affinity anti-IgM stimulation at a given time point (1 or 5 minutes). The mean percentage of maximum Δ values ± SD for several pooled experiments is presented.

Assay of tyrosine phosphorylation in proteins associated with the insoluble cytoskeleton.

To assess the degree of tyrosine phosphorylation in proteins associated with the insoluble cytoskeleton, the Triton X-100 insoluble pellet was washed once with 1 mL lysis buffer before being resuspended in 100 μL SDS-PAGE sample buffer + 5% 2-ME. The samples were boiled for 5 minutes and passed 10× through a 25-gauge needle as described by Gold et al.38 The samples were then spun for 5 minutes (14,000 rpm) and the supernatants were stored at −70°C. At the time of assay, a 10-μL aliquot of each boiled sample was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and assayed for protein tyrosine phosphorylation by ECL as described above.

Cell immunofluorescence assays.

In experiments with intact MoAb, the relative potential of the various anti-IgM MoAb to bind Ramos cells was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence assays followed by flow cytofluorimetric analysis with a FACScan equipped with Lysys II software (Becton Dickinson), as described elsewhere.34 In one set of experiments (see Fig3), 1 × 105 cells were incubated for 5 minutes with the primary MoAb at 37°C in a volume of 200 μL RPMI-1640 + 1% BSA + 15 mmol/L sodium azide + 50 mmol/L 2-deoxy-D-glucose to prevent receptor internalization and capping,39 before washing, reincubation with FITC-conjugated sheep F(ab′)2antimouse IgG Ab for 30 minutes at 4°C in assay buffer, additional washing, and fixation in 1% paraformaldehyde. In another set of experiments (see Fig 4), 1 × 105 cells were stained with the anti-IgM MoAbs (or isotype control MoAb) in a volume of 100 μL assay buffer (PBS + 1% BSA + 0.1% sodium azide) at 4°C for 45 minutes, before staining with secondary Ab, as described above.

Flow cytometric evaluation of the kinetics of anti-IgM Fab′ and F(ab′)2 dissociation.

FITC-conjugated HB57 and Mu53 F(ab′)2 were prepared by conjugation of purified F(ab′)2 fragments with 6-(fluorescein-5-(and -6)-carboxyamido) hexanoic acid, succinimidyl ester (Molecular Probes F-2181; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) using methods provided by the probe manufacturer. The conjugation ratios for these F(ab′)2 fragments were 12.9 and 13.2 mol of dye/mol of protein for HB57 and Mu53, respectively. The FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 were reduced and alkylated using previously described procedures30 to form FITC-Fab′ fragments and the reduction confirmed by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. For the dissociation experiments, Ramos cells (105) were incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature in a 0.3 mL volume with FITC-conjugated anti-IgM fragments (16.5 μg/mL; MoAb protein:cell ratio of 5 μg/105 cells) in medium containing 0.02% azide and 10 mmol/L 2-deoxy-D-glucose to prevent capping and internalization.39 After the 5-minute incubation period, a 0.3 mL volume of excess unlabeled MoAb HB57 (1 mg/mL) diluted in FACScan sheath fluid or, alternatively, sheath fluid alone was added. Flow cytometric analysis of the level of FITC fluorescence on scatter-gated cells was begun immediately after addition of sheath fluid with or without unlabeled protein, using a low flow rate and time as a parameter, for a total of 560 seconds. The events acquired throughout this period were gated into 80-second intervals (0 to 80 seconds, 81 to 160 seconds, etc), and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the cells acquired during each interval was determined with the use of the FACScan-associated Lysys II software (Becton Dickinson). The amount of nonspecific fluorescence of each ligand on Ramos cells was determined by preculturing Ramos cells for 5 minutes with a 90-fold excess of unlabeled MoAb HB57 before the 5 minutes of incubation with each FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 or F(ab′) ligand, as described above. The MFI values obtained during acquisition of cells during the first 40 seconds after the addition of 0.3 mL sheath fluid to the latter cells was taken as the amount of nonspecific binding. (Importantly, past experiments have shown that MoAb HB57 and MoAb Mu53 bind to proximal Cμ2 epitopes and that high-affinity MoAb HB57 is more effective at inhibiting binding of Mu53 to IgM than is intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 itself.33 Recent experiments confirmed that unlabeled HB57 and unlabeled Mu53 were equivalent at inducing the dissociation of FITC-Mu53 F(ab′)2 from Ramos IgM; data not shown.) The values for nonspecific binding were subtracted from each of the binding values obtained during the dissociation experiments. The amount of specific FITC–anti-IgM F(ab′)2 or Fab′ remaining bound after each 80-second interval was divided by the specific fluorescence noted during the initial 0- to 20-second time interval (t = 0), and this ratio was plotted versus time to obtain dissociation curves.

RESULTS

Assessment of affinity-diverse anti-IgM MoAbs for potential to induce apoptosis in Ramos B cells.

Three antihuman IgM MoAbs, specific for the same or proximal epitopes on the Cμ2 domain of mIgM but differing significantly in binding affinity,30,33 were evaluated for their potential to induce the in vitro apoptosis of Ramos B cells, as assessed by a change in the annexin-binding properties of the cells after 42 hours of culture. In these cultures, the MoAb was present at a concentration of 10 μg/mL (MoAb:cell ratio of 2 μg/105 cells; Fig 1). Consistent with prior reports,10,31 Ramos cells were induced to undergo apoptosis upon culture with anti-IgM Ab. However, the relative degree of apoptosis varied considerably depending on the ligand tested. Whereas nearly all of the Ramos cells became brightly annexin-positive after culture with intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 (Fab′ binding affinity of Ka = 2 × 107 mol/L−1), somewhat surprisingly, only a portion of the cells incubated with high-affinity MoAb HB57 (Ka = 5 × 108mol/L−1) did so. Cultures incubated with low-affinity MoAb P24 (Ka = ∼2 × 106 mol/L−1) did not become notably apoptotic. Additional studies with F(ab′)2 fragments have shown a similar pattern of apoptosis (data not shown), indicating that the difference between MoAb HB57 and MoAb Mu53 does not reflect a differing capacity of the MoAb to coengage mIgM and FcγRII (a molecule with negative regulatory effects on signal transduction through the mIg receptor complex).40Assessment of apoptosis by monitoring nuclei with hypodiploid levels of DNA36 or cells with a change in light scatter properties41 also showed that MoAb Mu53 induces a greater frequency of apoptotic cells than MoAb HB57 (data not shown). Time course studies showed that, although mIgM-triggered annexin-positive cells could be observed as early as 30 minutes after exposure to MoAb Mu53, maximal apoptosis was observed at 24 to 36 hours of culture (Fig 2). The proportion of annexin-positive B cells in cultures containing the high-affinity MoAb HB57 was always substantially less than that containing the intermediate-affinity MoAb, even after more prolonged incubation up to 60 hours (Fig 2; data not shown). Thus, the diminished level of apoptosis observed in cultures exposed to high-affinity MoAb HB57 does not appear to reflect slower kinetics for mIgM-triggered apoptosis by this ligand.

Murine MoAb with diverse affinities for human mIgM (Cμ2) differ in capacity to induce apoptosis in Ramos B cells. Cells were incubated with MoAb HB57, MoAb Mu53, MoAb P24, or isotype control MOPC-21 (MoAb concentration of 10 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells) for 42 hours before staining with FITC-annexin V and flow cytometric analysis. Apoptotic cells are indicated as those brightly positive for FITC-annexin V (see Materials and Methods). The intrinsic Fab′ binding affinities (Ka) of MoAbs HB57, Mu53, and P24 for B-cell mIgM are 5 × 108, 2 × 107, and approximately 2 × 106 mol/L−1, respectively.30 When the gate for annexin-positivity in the above experiment was set at a FITC-annexin intensity of 25 (horizontal log scale), Ramos cells incubated with isotype control MOPC or anti-IgM MoAbs P24, Mu53, and HB57 exhibited 4%, 4%, 90%, and 22% annexin-positive cells, respectively. Results similar to those above have been obtained in 12 replicate experiments. The difference between the percentage of annexin-positive cells in HB57 versus Mu53-treated cultures in the 12 replicate experiments was highly significant (mean ± SD of 38.2 ± 12.2 and 80.0 ± 10.3, respectively; P < .0001). Furthermore, the differences in the percentage of annexin-positive cells in HB57- or Mu53-treated cultures as compared with MOPC-treated control cultures (16.1 ± 8.8) were also both highly significant (P < .001).

Murine MoAb with diverse affinities for human mIgM (Cμ2) differ in capacity to induce apoptosis in Ramos B cells. Cells were incubated with MoAb HB57, MoAb Mu53, MoAb P24, or isotype control MOPC-21 (MoAb concentration of 10 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells) for 42 hours before staining with FITC-annexin V and flow cytometric analysis. Apoptotic cells are indicated as those brightly positive for FITC-annexin V (see Materials and Methods). The intrinsic Fab′ binding affinities (Ka) of MoAbs HB57, Mu53, and P24 for B-cell mIgM are 5 × 108, 2 × 107, and approximately 2 × 106 mol/L−1, respectively.30 When the gate for annexin-positivity in the above experiment was set at a FITC-annexin intensity of 25 (horizontal log scale), Ramos cells incubated with isotype control MOPC or anti-IgM MoAbs P24, Mu53, and HB57 exhibited 4%, 4%, 90%, and 22% annexin-positive cells, respectively. Results similar to those above have been obtained in 12 replicate experiments. The difference between the percentage of annexin-positive cells in HB57 versus Mu53-treated cultures in the 12 replicate experiments was highly significant (mean ± SD of 38.2 ± 12.2 and 80.0 ± 10.3, respectively; P < .0001). Furthermore, the differences in the percentage of annexin-positive cells in HB57- or Mu53-treated cultures as compared with MOPC-treated control cultures (16.1 ± 8.8) were also both highly significant (P < .001).

Kinetics of anti-IgM–induced apoptosis in Ramos B cells. Cells were incubated for the varying time intervals in the presence of isotype control MOPC-21 (A through G), HB57 anti-IgM (H through N), or Mu53 anti-IgM (O through U) (10 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells). Cultured cells were stained with FITC-annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig 1. The value shown in the upper right-hand corner of each histogram represents the percentage of cells that were brightly annexin-positive after each culture interval.

Kinetics of anti-IgM–induced apoptosis in Ramos B cells. Cells were incubated for the varying time intervals in the presence of isotype control MOPC-21 (A through G), HB57 anti-IgM (H through N), or Mu53 anti-IgM (O through U) (10 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells). Cultured cells were stained with FITC-annexin V and analyzed by flow cytometry as in Fig 1. The value shown in the upper right-hand corner of each histogram represents the percentage of cells that were brightly annexin-positive after each culture interval.

Figure 3 shows the relative degree of apoptosis (Fig 3A) and the relative degree of cell binding (Fig 3B) associated with various MoAb concentrations of high-affinity MoAb HB57 and intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 (MoAb:cell ratios of 0.04 μg/105 cells to 20 μg/105 cells). These experiments indicated (1) that the lower-binding anti-IgM MoAb Mu53 is superior to the high-binding anti-IgM MoAb HB57 at inducing apoptosis at all concentrations tested and (2) that maximal apoptosis by each ligand appears to occur at concentrations for maximal receptor occupancy by that MoAb.

Comparison of various concentrations of high-affinity MoAb HB57 and intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 for induction of apoptosis and binding to membrane IgM. (A) Apoptosis assay. Ramos B cells were cultured (22 to 24 hours) with the indicated concentrations of MoAb or medium alone before staining with FITC-annexin, as in Fig 1. The percentage of annexin-positive cells in medium cultures was subtracted from the percentage of annexin-positive cells in anti-IgM cultures to give ▵ percentage annexin-positive cells. The data shown represent the mean ± SD from two experiments. (B) Binding assay. Cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of MoAb HB57, Mu53, or isotype control MOPC-21 for 5 minutes at 37°C, under conditions that prevent ligand internalization and capping (Materials and Methods). MoAb binding was detected by indirect immunofluorescence. The data are expressed as the MFI above the background noted with isotype control MOPC-21 (ie, ▵ MFI). Similar results to the binding experiment shown were obtained in an additional experiment performed at 37°C and in two experiments performed at 4°C. For both the apoptosis and the binding experiments, MoAb concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL correspond to MoAb:cell ratios of 0.2 μg/105 cells, 2 μg/105 cells, and 20 μg/105 cells, respectively.

Comparison of various concentrations of high-affinity MoAb HB57 and intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 for induction of apoptosis and binding to membrane IgM. (A) Apoptosis assay. Ramos B cells were cultured (22 to 24 hours) with the indicated concentrations of MoAb or medium alone before staining with FITC-annexin, as in Fig 1. The percentage of annexin-positive cells in medium cultures was subtracted from the percentage of annexin-positive cells in anti-IgM cultures to give ▵ percentage annexin-positive cells. The data shown represent the mean ± SD from two experiments. (B) Binding assay. Cells were exposed to the indicated concentrations of MoAb HB57, Mu53, or isotype control MOPC-21 for 5 minutes at 37°C, under conditions that prevent ligand internalization and capping (Materials and Methods). MoAb binding was detected by indirect immunofluorescence. The data are expressed as the MFI above the background noted with isotype control MOPC-21 (ie, ▵ MFI). Similar results to the binding experiment shown were obtained in an additional experiment performed at 37°C and in two experiments performed at 4°C. For both the apoptosis and the binding experiments, MoAb concentrations of 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL correspond to MoAb:cell ratios of 0.2 μg/105 cells, 2 μg/105 cells, and 20 μg/105 cells, respectively.

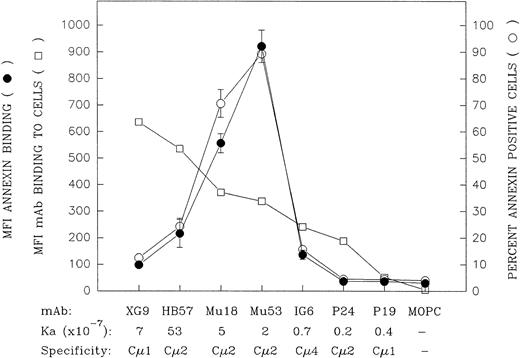

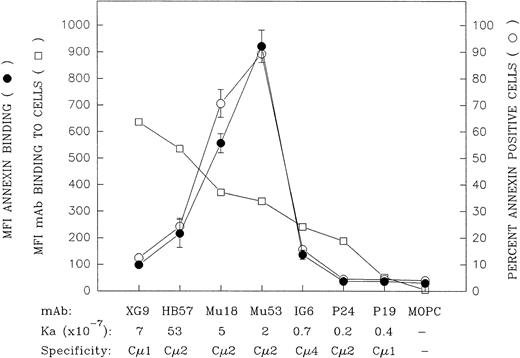

A more extensive panel of anti-IgM MoAb with differing anti-IgM domain specificities and affinities was evaluated, at a concentration of 10 μg/mL, for capacity to induce apoptosis as well as for binding to mIgM (Fig 4). (The MoAb:cell ratio for these experiments was 2 μg per 105 cells for the apoptosis assay and 1 μg per 105 cells for the binding assay.) These experiments further confirmed the observation that the MoAbs that were the best at binding mIgM, as determined by an indirect immunofluorescent assay with bivalent MoAb, were not the most effective at inducing apoptosis. Rather, the ligands that triggered the highest levels of apoptosis were those that exhibited an intermediate degree of binding to Ramos cells, ie, MoAb Mu18 and Mu53. (At this MoAb concentration, all of the ligands, with the exception of the lower-affinity MoAbs IG6, P24, and P19, exhibited plateau level binding [data not shown].)

Comparison of the mIgM-binding and apoptosis-inducing properties of a large panel of bivalent anti-IgM MoAbs with differing intrinsic affinity and differing IgM domain specificity. The capacity of the bivalent MoAb to bind Ramos mIgM was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence following 30 minutes of incubation of Ramos cells with 10 μg/mL of MoAb at 4°C (MoAb:cell ratio = 1 μg/105 cells). Data are indicated as the MFI (□). The MoAbs are listed (left to right) in descending order of their mIgM binding potential by this assay. With the notable exception of MoAb XG9, there was a relatively good correspondence between relative binding potential of the bivalent MoAb and the previously established Ka values for binding of MoAb Fab′.30 The capacity of these ligands to induce apoptosis was assessed by culturing Ramos cells with 10 μg/mL of each MoAb (MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells) for 42 hours and subsequent staining with FITC-annexin. The later results are shown as MFI FITC-annexin bound (•) as well as the percentage of annexin-positive cells (○); (mean ± SD from 2 experiments). A further replicate experiment in which all the MoAbs, with the exception of Mu18, were evaluated for MoAb binding or capacity to induce annexin-positive cells upon in vitro culture yielded similar results to those shown above.

Comparison of the mIgM-binding and apoptosis-inducing properties of a large panel of bivalent anti-IgM MoAbs with differing intrinsic affinity and differing IgM domain specificity. The capacity of the bivalent MoAb to bind Ramos mIgM was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence following 30 minutes of incubation of Ramos cells with 10 μg/mL of MoAb at 4°C (MoAb:cell ratio = 1 μg/105 cells). Data are indicated as the MFI (□). The MoAbs are listed (left to right) in descending order of their mIgM binding potential by this assay. With the notable exception of MoAb XG9, there was a relatively good correspondence between relative binding potential of the bivalent MoAb and the previously established Ka values for binding of MoAb Fab′.30 The capacity of these ligands to induce apoptosis was assessed by culturing Ramos cells with 10 μg/mL of each MoAb (MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells) for 42 hours and subsequent staining with FITC-annexin. The later results are shown as MFI FITC-annexin bound (•) as well as the percentage of annexin-positive cells (○); (mean ± SD from 2 experiments). A further replicate experiment in which all the MoAbs, with the exception of Mu18, were evaluated for MoAb binding or capacity to induce annexin-positive cells upon in vitro culture yielded similar results to those shown above.

Whereas the relative degree to which the seven bivalent anti-IgM MoAbs bound Ramos cells in the indirect immunofluorescence assay was generally in agreement with their Fab′ intrinsic binding affinities for mIgM,30 this was not the case with MoAb XG9. Although previous equilibrium binding studies with MoAb Fab′ fragments showed this latter Cμ1-specific MoAb to have an intrinsic affinity lower than that of MoAb HB57 (7 × 107v 5 × 108 mol/L−1, respectively),30 bivalent MoAb XG9 bound Ramos to a greater degree than did bivalent MoAb HB57 in the indirect immunofluorescence assay. As will be discussed below, the greater binding of bivalent MoAb XG9 is probably, at least in part, attributed to the established propensity of this Cμ1-specific MoAb to bind in a monogamous fashion to mIgM, ie, both Fab binding sites on the XG9 MoAb engaged with both Fab epitopes on a single mIgM molecule.30 Others have discussed how such bivalent binding to two epitopes on the same molecule results in quite stable engagement, ie, provides a substantial avidity bonus.42 Hence, MoAb XG9 would less likely dissociate from mIgM during the washing procedures associated with the staining assay.

Assessment of affinity-diverse anti-Cμ2-specific MoAbs at inducing protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Ramos cells.

Although a tendency toward monogamous binding, and hence a lesser capacity to cross-link separate mIgM molecules, may explain the lesser capacity of high-affinity MoAb XG9 to induce apoptosis, the reason for the suboptimal apoptosis triggered by the high-affinity MoAb HB57 is less apparent. In an effort to gain further insight into why the high- and intermediate-affinity Cμ2-specific MoAbs affinity differ so substantially at triggering apoptosis, we have compared the relative capacity of these ligands to induce early protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Ramos cells. Such studies have the potential of showing whether the lowered effectiveness of the high-affinity MoAb at inducing apoptosis is due to a supraoptimal or suboptimal level of mIgM signal transduction or, alternatively, to a qualitatively different pattern of early tyrosine phosphorylation.

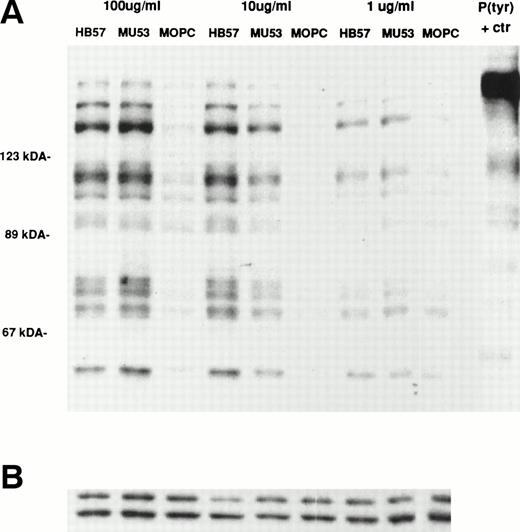

Ramos cells were stimulated for 1 or 5 minutes with the affinity-diverse Cμ2-specific MoAbs (HB57, Mu53, and P24) or isotype control MOPC-21 (MoAb concentration of 100 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio of 5 μg/105 cells). The degree of tyrosine phosphorylation of various cellular proteins was assessed after gel electrophoresis of lysates, Western blotting with HRP-conjugated anti-P(tyr) MoAb, and ECL. Our studies (data not shown) and those of others18 38had shown that, at these time intervals, B cells typically exhibit maximal tyrosine phosphorylation of most proteins. The data in Fig 5 indicate that, as noted for apoptosis, the bivalent high-affinity anti-IgM MoAb HB57 was less effective than the intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 at triggering the early (1 and 5 minutes) tyrosine phosphorylation of multiple proteins in Ramos cells. No obvious qualitative differences were noted in the proteins that were tyrosine phosphorylated after MoAb HB57 or MoAb Mu53 engagement with B cells. Both MoAb HB57 and MoAb Mu53 were substantially more effective than low-affinity MoAb P24 in inducing tyrosine phosphorylation.

Relative capacity of MoAb with high, intermediate, and low affinity for mIgM (Cμ2) to induce early protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Ramos B cells. Cells were incubated with high-affinity MoAb HB57, intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, low-affinity MoAb P24, or isotype control MOPC-21 at a concentration of 100 μg/mL (MoAb:cell ratio = 5 μg/105 cells) for 1 or 5 minutes before preparation of lysates and (A) analysis of lysates (20 μg protein) for tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting with HRP-conjugated anti-P(tyr) Ab, and ECL, as described in Materials and Methods. A P(tyr)-positive control lysate (1:20 dilution) was run on both the 1- and 5-minutes lysate gels. The position of MW standards is shown on the left as approximate kilodaltons. The position and designation of several P(tyr) proteins that were densitometrically analyzed (as in Fig 6) is shown in the center as p137, p96, p78, and p60. (B) Blots were stripped and reanalyzed by Western blotting with rabbit anticatalase and HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG and ECL, as described in Materials and Methods, as a control for the amount of loaded protein.

Relative capacity of MoAb with high, intermediate, and low affinity for mIgM (Cμ2) to induce early protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Ramos B cells. Cells were incubated with high-affinity MoAb HB57, intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, low-affinity MoAb P24, or isotype control MOPC-21 at a concentration of 100 μg/mL (MoAb:cell ratio = 5 μg/105 cells) for 1 or 5 minutes before preparation of lysates and (A) analysis of lysates (20 μg protein) for tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting with HRP-conjugated anti-P(tyr) Ab, and ECL, as described in Materials and Methods. A P(tyr)-positive control lysate (1:20 dilution) was run on both the 1- and 5-minutes lysate gels. The position of MW standards is shown on the left as approximate kilodaltons. The position and designation of several P(tyr) proteins that were densitometrically analyzed (as in Fig 6) is shown in the center as p137, p96, p78, and p60. (B) Blots were stripped and reanalyzed by Western blotting with rabbit anticatalase and HRP-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG and ECL, as described in Materials and Methods, as a control for the amount of loaded protein.

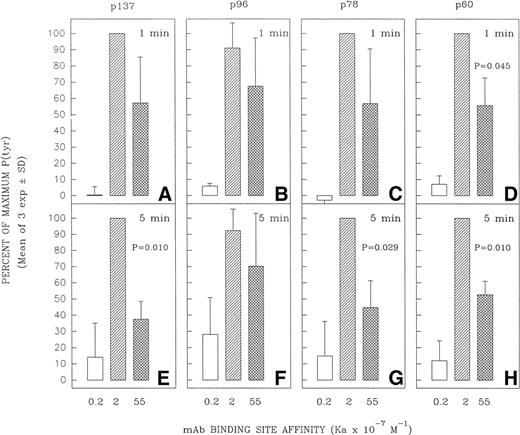

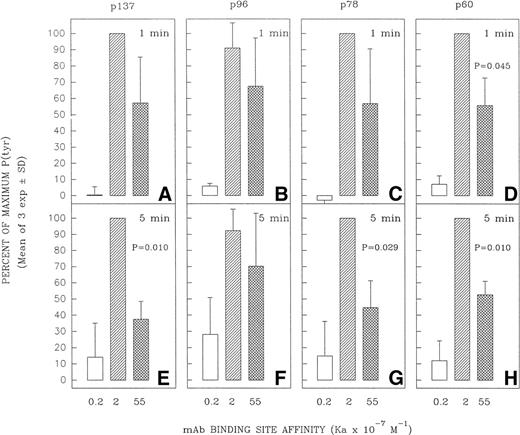

Several tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were selected for densitometric evaluation based on the fact that they were the most consistently resolvable in the multiple blots performed in replicate experiments. A densitometric evaluation of the intensity of the P(tyr) proteins designated as p137, p78, and p60 (based on their approximate MW in kilodaltons) showed that the high-affinity MoAb was less effective than the intermediate-affinity ligand at inducing the phosphorylation of these proteins in multiple experiments (Fig 6). A possible exception was in the case of the protein, p96, which in several experiments appeared to be phosphorylated to a more comparable degree by the high-affinity and intermediate-affinity ligands. We have not performed analyses to confirm the identity of p137, p96, p78, and p60. However, anti-P(tyr) immunoblotting of anti-phospholipase C-γ2 (PLC-γ2) immunoprecipitates of Ramos cells stimulated with MoAbs HB57, Mu53, P24, and MOPC-21 showed a more intense tyrosine phosphorylated band of approximately 137 kD in the immunoprecipitated lysate of MoAb Mu53-stimulated cells, under conditions in which reblotting with anti–PLC-γ2 showed comparable levels of PLC-γ2 at the same position in all immunoprecipitates (data not shown). This suggests that PLC-γ2 is one protein whose tyrosine phosphorylation is more effectively achieved by the intermediate-affinity MoAb.

Effect of anti-IgM MoAb affinity on potential to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins designated as p137, p96, p78, and p60. Ramos B cells were stimulated for 1 or 5 minutes with the affinity-diverse anti-IgM MoAbs and the lysates analyzed as in Fig 5. The designated protein bands in the antiphosphotyrosine blots (eg, Fig5) were densitometrically analyzed as detailed in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as the percentage of the maximal anti-IgM–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed for each protein at a given time point. The mean ± SD of the percentage of maximum values for three separate experiments is shown. The paired Student’s t-test was used to evaluate whether the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of a given protein induced by MoAb HB57 (Ka = 55 × 107 mol/L−1) was significantly different from that induced by MoAb Mu53 (Ka = 2 × 107mol/L−1). P (probability) values that approached or were less than P = .05 are indicated above the bars representing the response to MoAb HB57.

Effect of anti-IgM MoAb affinity on potential to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of proteins designated as p137, p96, p78, and p60. Ramos B cells were stimulated for 1 or 5 minutes with the affinity-diverse anti-IgM MoAbs and the lysates analyzed as in Fig 5. The designated protein bands in the antiphosphotyrosine blots (eg, Fig5) were densitometrically analyzed as detailed in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as the percentage of the maximal anti-IgM–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed for each protein at a given time point. The mean ± SD of the percentage of maximum values for three separate experiments is shown. The paired Student’s t-test was used to evaluate whether the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of a given protein induced by MoAb HB57 (Ka = 55 × 107 mol/L−1) was significantly different from that induced by MoAb Mu53 (Ka = 2 × 107mol/L−1). P (probability) values that approached or were less than P = .05 are indicated above the bars representing the response to MoAb HB57.

To discern whether the variability in the relative degree of protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed in the diverse experiments shown in Fig 6 might represent variability intrinsic to the assay (intraexperimental variability) or variability between stimulation experiments (interexperimental variability), we compared the relative degree of protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed when a set of lysates from a single Ramos stimulation experiment was assayed on three different occasions by gel electrophoresis, Western blotting, and ECL detection of P(tyr) proteins. The data in Fig 7A through D indicate that the replicate blots from a single set of lysates (1 minute of stimulation) exhibited greater uniformity than did blots from lysates derived from multiple Ramos stimulation experiments (Fig 6A through D). This suggests that the degree of variability in the effect of MoAb affinity on protein tyrosine phosphorylation in part reflects subtle differences in the Ramos cell population used for the different experiments. The nature of these differences is not known but may possibly reflect differences in the cell cycle stage of the majority of the cells and/or in the relative IgM density or rate of receptor diffusion at the time of testing.

Intraexperimental variability in the degree of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. A set of lysates from one of the three stimulation experiments in Fig 6 was reassayed on different occasions by anti-P(tyr) immunoblotting and ECL. Bands were analyzed and plotted as in Fig 6. The tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins indicated as p78 and p60 were analyzed in three replicate assays with the same lysate. Data shown for p137 and p96 represent only two of the assays, due to problems in the clear resolution of p137 and p96 in one of the assays.

Intraexperimental variability in the degree of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. A set of lysates from one of the three stimulation experiments in Fig 6 was reassayed on different occasions by anti-P(tyr) immunoblotting and ECL. Bands were analyzed and plotted as in Fig 6. The tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins indicated as p78 and p60 were analyzed in three replicate assays with the same lysate. Data shown for p137 and p96 represent only two of the assays, due to problems in the clear resolution of p137 and p96 in one of the assays.

Components of the mIg signaling complex have been reported to associate with cytoskeletal elements after receptor cross-linking.43To investigate whether the diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of detergent-soluble proteins in HB57-stimulated cells might be explained by an increased phosphorylation of proteins in the detergent-insoluble cytoskeleton, we evaluated the level of tyrosine phosphorylation evident in the Triton X-insoluble pellet. Whereas tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins of approximately 70 to 77 kD MW could be detected in these fractions at 1 and 5 minutes after stimulation with 100 μg/mL anti-IgM MoAb, these proteins were not phosphorylated to a greater degree in high-affinity MoAb HB57-stimulated cells than in intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53-stimulated cells. Rather, the inverse was the case (data not shown), as noted for the detergent-soluble proteins (Figs 5 and 6).

Taken together, the available data indicate that the impaired capacity of a high-affinity bivalent anti-IgM MoAb to trigger apoptosis of Ramos B cells cannot be attributed to a supraoptimal level of mIgM signal transduction after ligand binding or to any obvious difference in the proteins that are tyrosine phosphorylated after MoAb engagement. Rather, the lowered capacity of the high-affinity ligand to induce apoptosis may correlate with a lowered capacity to induce signal transduction, as manifest by the overall degree of tyrosine phosphorylation observed after brief culture with high concentrations of MoAb.

Evidence that intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 induces a greater degree of receptor cross-linking than high-affinity MoAb HB57.

A lesser capacity of high-affinity ligands to induce mIgM signal transduction might reflect a diminished capacity of the high-affinity bivalent ligand to induce receptor cross-links at high, receptor-saturating concentrations. This hypothesis is supported by previous studies on the kinetics of univalent and bivalent engagement of MoAbs specific for other cell surface molecules.42 44-46The latter studies have shown that, at high concentrations, high-affinity bivalent ligands will have a propensity for engaging stably via one binding site only (univalent binding), whereas lower-affinity ligands will more rapidly evolve into a state in which both binding sites are engaged with two surface molecules (bivalent bridge binding). We have attempted to experimentally address this through two types of experiments.

Firstly, we compared the extent to which the intermediate- and high-affinity Cμ2-specific MoAbs, Mu53 and HB57, induce mIgM patching and capping when incubated with Ramos cells for 15 minutes at 37°C (10 μg/mL MoAb; MoAb:cell ratio of 0.5 μg/105 cells). The summarized data in Table 1 indicate that, although MoAb HB57 was able to induce mIgM redistribution on Ramos B cells, it was significantly less effective at doing so than the intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53. (Similar conclusions were reached in an additional experiment in which the MoAbs were tested at a higher concentration of 100 μg/mL [MoAb:cell ratio of 5 μg/105 cells].) Additionally, the Cμ1-specific MoAb XG9 was found to be impaired in capacity to induce mIgM cross-linking, as compared with MoAb Mu53.

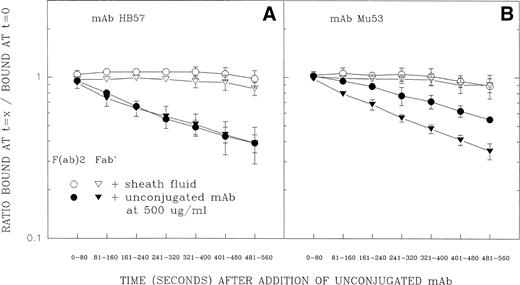

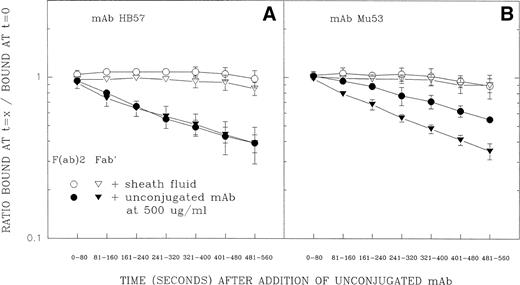

The second test of the above-described hypothesis involved flow cytometric measurements of the dissociation rates of cell-bound FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 and Fab′ fragments of MoAb HB57 and MoAb Mu53 in the presence of excess unlabeled MoAb (Fig 8). (FITC-labeled ligand was added at a MoAb protein:cell ratio of 5 μg/105 cells at ambient temperature.) Other studies have indicated that, in the presence of excess ligand, differences in the rate of dissociation of cell-bound labeled F(ab′)2 and Fab′ fragments should reflect the extent of univalent or bivalent binding to cell receptors.47-49 The competing unlabeled ligand prevents dissociated binding sites of the FITC-labeled Ab from re-engaging with their cellular epitopes; FITC-ligand bound through only one Fab′ will relatively rapidly release from the cell, whereas ligand bound through both binding sites will release from the cell more slowly (due to the necessity for dissociation of two separate binding sites). The data in Fig 8 show that, whereas FITC-HB57 F(ab′)2and FITC-HB57 Fab′ had comparable rates of dissociation, the dissociation of FITC-Mu53 F(ab′)2 was substantially slower than that of monovalent FITC-Mu53 Fab′. This indeed suggests that, under these conditions, bivalent MoAb HB57 binds predominantly via one site (univalently), whereas bivalent MoAb Mu53 undergoes a substantial degree of bivalent engagement. In these experiments, the dissociation rate constant (k2)50 (mean ± SD of 3 experiments) for Mu53 Fab′ (2.23 ± 0.25 × 10−3[s−1]) was found to be only slightly faster than that for HB57 Fab′ (1.81 ± 0.10 × 10−3 [s−1]) (P value by Student’s t-test = .052). The substantially greater equilibrium binding constant (Ka) for HB57 Fab′ versus Mu53 Fab′30 might be explained by temperature effects on Fab′ dissociation50 or by a greater association rate for MoAb HB57 versus MoAb Mu53. These issues will require further experimentation.

Dissociation of FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2and Fab′ fragments of MoAb HB57 (A) or MoAb Mu53 (B) from Ramos cells in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled antibody. Cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 (○, •) or Fab′ (▵, ▴) fragments of high-affinity MoAb HB57 (A) or intermediate affinity Mu53 (B) (16.5 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio equal to that used for tyrosine phosphorylation experiment in Fig 5, ie, 5 μg/105 cells) for 5 minutes before addition of an excess of unlabeled MoAb HB57 diluted in sheath fluid or the addition of sheath fluid alone, as described in Materials and Methods. Flow cytometric analysis of the level of FITC-fluorescence was begun immediately after the addition of sheath fluid with or without unlabeled protein, using time as a parameter, for a total of 560 seconds. The amount of specific fluorescence at each 80-second time interval (t = x) was determined as described in Materials and Methods and is plotted above as a ratio of the specific fluorescence during each time interval relative to the specific fluorescence noted in the same tube at t = 0 to 20 seconds (ie, t = 0). At this latter time interval, there was no notable difference between the engagement of ligand to cells with or without unconjugated MoAb present (data not shown).

Dissociation of FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2and Fab′ fragments of MoAb HB57 (A) or MoAb Mu53 (B) from Ramos cells in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled antibody. Cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 (○, •) or Fab′ (▵, ▴) fragments of high-affinity MoAb HB57 (A) or intermediate affinity Mu53 (B) (16.5 μg/mL; MoAb:cell ratio equal to that used for tyrosine phosphorylation experiment in Fig 5, ie, 5 μg/105 cells) for 5 minutes before addition of an excess of unlabeled MoAb HB57 diluted in sheath fluid or the addition of sheath fluid alone, as described in Materials and Methods. Flow cytometric analysis of the level of FITC-fluorescence was begun immediately after the addition of sheath fluid with or without unlabeled protein, using time as a parameter, for a total of 560 seconds. The amount of specific fluorescence at each 80-second time interval (t = x) was determined as described in Materials and Methods and is plotted above as a ratio of the specific fluorescence during each time interval relative to the specific fluorescence noted in the same tube at t = 0 to 20 seconds (ie, t = 0). At this latter time interval, there was no notable difference between the engagement of ligand to cells with or without unconjugated MoAb present (data not shown).

High-affinity MoAb HB57 prevents apoptosis triggered by intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53.

As indicated in the above-described dissociation experiments and elsewhere,33 MoAb HB57 can very effectively inhibit the binding of Mu53 to its proximal Cμ2 epitope.33 One might therefore predict that, if the greater capacity of MoAb Mu53 to induce apoptosis were due to a greater capacity to induce cross-linking of mIgM, the addition of saturating concentrations of the high-affinity MoAb HB57 to cultures containing MoAb Mu53 would ablate the ability of MoAb Mu53 to induce apoptosis. Consistent with these expectations, we observed that the presence of 10 to 100 μg/mL concentrations of MoAb HB57 significantly abrogated the capacity of similar concentrations of MoAb Mu53 to induce apoptosis (Table 2).

An enhancement in the mIgM cross-linking capacity of high-affinity anti-IgM MoAb can reverse the impairment in triggering apoptosis.

We examined whether efforts to enhance the cross-linking potential of a high-affinity ligand would substantially enhance its efficacy at triggering apoptosis. This involved testing the capacity of MoAb HB57 and MoAb Mu53 to induce apoptosis as multivalent MoAb:dextran conjugates. The data in Fig 9 shows that the multivalent form of MoAb HB57 was as effective as the multivalent form of MoAb Mu53 at inducing Ramos apoptosis at a concentration (ie, 10 μg/mL) at which the bivalent forms of the two MoAbs were significantly different at inducing apoptosis. The findings given above are in agreement with the studies of Chaouchi et al10 and Marches et al18 using Ramos and Daudi cells, respectively, which had shown that secondary cross-linking Ab could increase the degree of protein tyrosine phosphorylation elicited by MoAb DA4.4 (HB57) as well as facilitate apoptosis by this MoAb. Additional studies in this laboratory with Ramos cells have shown that the addition of a secondary cross-linking Ab to MoAb HB57-containing cultures results in levels of apoptosis equivalent to that in MoAb Mu53-containing cultures (data not shown).

The impaired capacity of high-affinity MoAb to induce apoptosis is not observed under conditions of ligand multivalency. Cells were cultured for 42 hours with bivalent forms of high-affinity MoAb HB57, intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, or isotype control MOPC-21 or with multivalent MoAb:dextran conjugates of MoAb HB57, MoAb Mu53, or MOPC-21 (as HB57:UPC:dextran, Mu53:UPC:dextran, and MOPC-21:UPC:dextran; see Materials and Methods) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL MoAb protein per culture (MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells). Apoptosis was assessed by FITC-annexin V binding as in Fig 1. The results represent the mean percentage of annexin-positive cells in two experiments ± SEM.

The impaired capacity of high-affinity MoAb to induce apoptosis is not observed under conditions of ligand multivalency. Cells were cultured for 42 hours with bivalent forms of high-affinity MoAb HB57, intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, or isotype control MOPC-21 or with multivalent MoAb:dextran conjugates of MoAb HB57, MoAb Mu53, or MOPC-21 (as HB57:UPC:dextran, Mu53:UPC:dextran, and MOPC-21:UPC:dextran; see Materials and Methods) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL MoAb protein per culture (MoAb:cell ratio = 2 μg/105 cells). Apoptosis was assessed by FITC-annexin V binding as in Fig 1. The results represent the mean percentage of annexin-positive cells in two experiments ± SEM.

High-affinity anti-IgM MoAb is not impaired in capacity to induce early protein tyrosine phosphorylation at less saturating ligand concentrations.

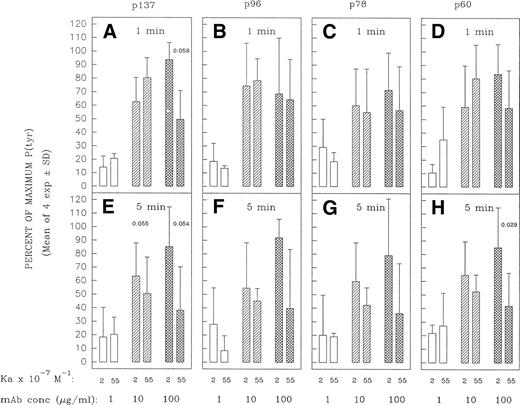

Although bivalent, high-affinity MoAbs can be compromised in capacity to form cross-links at high saturating ligand concentrations,42 44-46 this is not expected at subsaturating concentrations of ligand. Under the latter conditions, a greater proportion of free receptor molecules should increase the likelihood that the bivalent MoAb can engage both its binding sites and hence bridge IgM molecules. One might thus expect a lesser disparity between MoAb HB57 and MoAb Mu53 at initiating cross-link–dependent signaling events at low MoAb concentrations. Consistent with these expectations, we did observe an enhancement in the capacity of high-affinity anti-IgM to induce early protein tyrosine phosphorylation when the concentration was lowered from 100 to 10 μg/mL (5 μg per 105 cells v 0.5 μg per 105 cells, respectively). Thus, as the concentration of ligand diminished, the high-affinity MoAb was no longer impaired, relative to the intermediate-affinity MoAb, in capacity to induce the rapid tyrosine phosphorylation of most proteins (Figs 10and 11); indeed, in occasional experiments, MoAb HB57 was more effective than MoAb Mu53 at inducing protein tyrosine phosphorylation at the lower MoAb:cell ratio (eg, Fig10). Furthermore, whereas intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 generally induced the greatest level of tyrosine phosphorylation at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, the greatest level of MoAb HB57-induced tyrosine phosphorylation was more typically noted at the lower concentration of 10 μg/mL (Fig 11). Interestingly, despite the effectiveness of the high-affinity MoAb at inducing early protein tyrosine phosphorylation at the lower ligand concentrations, we did not observe an enhancement in the apoptosis-inducing potential of the high-affinity MoAb at low subsaturating concentrations (Fig 3).

Protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Ramos B cells after 1 minute of incubation with various concentrations of high- or intermediate-affinity anti-IgM. Ramos cells were incubated for 1 minute with the indicated concentrations of high-affinity MoAb HB57, intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, or isotype control MOPC-21 (100 μg/mL = MoAb:cell ratio of 5 μg/105 cells; 10 μg/mL = 0.5 μg/105 cells; 1 μg/mL = 0.05 μg/105 cells). (A) Tyrosine-phosphorylated protein was assayed as described in Fig 5, with the exception that 5 μg of lysate was loaded per lane. (B) Blots were stripped and reblotted with anticatalase as described in Fig 5.

Protein tyrosine phosphorylation in Ramos B cells after 1 minute of incubation with various concentrations of high- or intermediate-affinity anti-IgM. Ramos cells were incubated for 1 minute with the indicated concentrations of high-affinity MoAb HB57, intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, or isotype control MOPC-21 (100 μg/mL = MoAb:cell ratio of 5 μg/105 cells; 10 μg/mL = 0.5 μg/105 cells; 1 μg/mL = 0.05 μg/105 cells). (A) Tyrosine-phosphorylated protein was assayed as described in Fig 5, with the exception that 5 μg of lysate was loaded per lane. (B) Blots were stripped and reblotted with anticatalase as described in Fig 5.

Densitometric analysis of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in Ramos cells incubated with varying concentrations of high- and intermediate-affinity anti-IgM for 1 or 5 minutes. Ramos cells were stimulated as in Fig 10 in four separate experiments. The tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins designated p137, p96, p78, and p60 (see Figs 5 and 6) were densitometrically analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as the percentage of the maximal anti-IgM–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed for each protein at a given time point. The mean ± SD of the percentage of maximum values for the four separate experiments is shown, with the exception of data for cells incubated with the low (1 μg/mL) concentration of MoAb. This concentration was tested in only three of four of these experiments. The paired Student’st-test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference in protein tyrosine phosphorylation of a given protein elicited by high-affinity MoAb HB57 as compared with intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, at a given concentration. P (probability) values that approached or were less than P = .05 are indicated.

Densitometric analysis of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in Ramos cells incubated with varying concentrations of high- and intermediate-affinity anti-IgM for 1 or 5 minutes. Ramos cells were stimulated as in Fig 10 in four separate experiments. The tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins designated p137, p96, p78, and p60 (see Figs 5 and 6) were densitometrically analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as the percentage of the maximal anti-IgM–induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed for each protein at a given time point. The mean ± SD of the percentage of maximum values for the four separate experiments is shown, with the exception of data for cells incubated with the low (1 μg/mL) concentration of MoAb. This concentration was tested in only three of four of these experiments. The paired Student’st-test was used to evaluate the significance of the difference in protein tyrosine phosphorylation of a given protein elicited by high-affinity MoAb HB57 as compared with intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, at a given concentration. P (probability) values that approached or were less than P = .05 are indicated.

Optimal induction of apoptosis may require sustained mIgM signal transduction.

One possible explanation for the impaired induction of apoptosis, despite effective induction of early protein tyrosine phosphorylation by lower concentrations of high-affinity anti-IgM MoAb, is that the high-affinity MoAb may be less capable of sustaining chronic or serial signaling events that may be needed for optimal induction of apoptosis. In an effort to examine whether early 1- to 5-minute signal transduction is sufficient for the induction of apoptosis, we have attempted to block the formation of new mIgM cross-links at various times after MoAb culture with Ramos B cells by the addition of an excess of soluble human IgM myeloma protein. The effect of this intervention on the induction of annexin-positive cells 1 hour after anti-IgM exposure to the B cells was evaluated.

The representative experiment shown in Table 3 indicates that, although full abrogation of 1-hour MoAb Mu53-induced apoptosis was best achieved when the soluble IgM inhibitor was present at the beginning of culture (t = 0), significant inhibition was observed when the inhibitor was delayed up to 30 minutes after initial exposure to the mIgM–cross-linking ligand. These observations indicate that the early 1- to 5-minute burst in protein tyrosine phosphorylation observed after MoAb exposure to Ramos B cells is not sufficient for the induction of apoptosis in most cells.

DISCUSSION

The above-mentioned study has provided evidence for a somewhat unexpected influence of affinity in triggering antigen receptor-induced apoptosis of transformed B cells by anti-Ig MoAb. Thus, although it was observed that anti-IgM MoAb must engage Ramos B-cell mIgM with a minimal threshold affinity to elicit apoptosis, there was also a maximal affinity threshold above which MoAbs appeared to be compromised in their capacity to induce apoptotic cell death. Although the anti-IgM MoAbs evaluated in this in vitro study would not be useful at modulating B-cell function in vivo, due to the high levels of competing soluble IgM, the findings with these MoAbs may be of general relevance for the therapeutic use of other MoAbs whose efficacy requires receptor cross-linking.

The lesser capacity of high-affinity MoAbs to induce apoptosis likely reflects several factors. Firstly, signal transduction via mIgM requires receptor cross-linking.51 Secondly, receptor cross-linking minimally involves a two-step process. Initial binding occurs upon ligation of one MoAb binding site, and this is followed by engagement of the subsequent MoAb binding site to an unoccupied epitope on a second proximal receptor.42,44-46 Importantly, differences in intrinsic affinity (ie, differences in association rate or dissociation rate for the first bond formation) as well as receptor density and MoAb concentration will have an impact on the ease of forming receptor cross-links.42 44-46 High ligand concentrations, such as those needed for inducing optimal apoptosis, can diminish the number of free receptor epitopes available for promoting receptor cross-linking. This is particularly the case if the ligand has high affinity and can rapidly saturate all receptors via one-site binding (fast k+1 association rate) and/or remain stably bound via one site (slow k−1dissociation rate).

A number of observations strongly suggest that the lesser potential of high-affinity MoAb HB57 to induce the apoptosis of Ramos B cells is, at least in part, explained by a diminished capacity for receptor cross-linking. (1) MoAb HB57 was less effective than intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 at inducing mIgM patching and capping on Ramos B cells. (2) Dissociation experiments showed that MoAb HB57 exhibits a higher proportion of univalent binding than does intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 after 5 minutes of exposure to Ramos B cells. (3) At saturating concentrations of ligand, almost twice as many MoAb HB57 than intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 molecules bound Ramos, consistent with a high degree of univalent engagement (as well as a greater stability of bivalently engaged ligand). (4) At high MoAb concentrations, MoAb HB57 exhibited an impaired capacity to induce the early protein tyrosine phosphorylation that directly follows receptor cross-linking. (5) Saturating concentrations of MoAb HB57 ablated the capacity of MoAb Mu53 to induce apoptosis. Finally, attempts to increase the cross-linking potential of MoAb HB57, by covalently coupling multiple MoAb to high MW dextran, significantly increased the potential of this MoAb to induce Ramos B-cell apoptosis. A greater degree of univalent binding might help explain the unexpectedly poor capacity of certain other MoAbs with high mIg binding activity to induce Ca2+ mobilization and apoptosis.5

Interestingly, when the MoAb concentration was lowered to less saturating levels that should favor receptor cross-linking, the high-affinity MoAb HB57 was no longer compromised (relative to the intermediate-affinity MoAb) at inducing early protein tyrosine phosphorylation, yet it remained impaired in capacity to induce apoptosis. This suggests that the quantitative, qualitative, or temporal engagements needed for the induction of the two phenomena are different and that the induction of apoptosis is not solely dependent on the magnitude of early protein tyrosine phosphorylation. The latter conclusion was supported by studies in which soluble IgM myeloma protein was added as a competitive inhibitor for MoAb Mu53 anti-IgM binding to B cells. Not only could soluble IgM fully inhibit anti-IgM–triggered apoptosis when added at culture initiation, but it also inhibited the induction of apoptosis by 82% when added 1 to 5 minutes after B-cell exposure to the anti-IgM MoAb, ie, after the initial burst in protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Taken together, the available information strongly suggests that the induction of apoptosis, similarly to the induction of other functional phenomena in lymphocytes, may require more than a one-hit ligand:receptor interaction.2,19,20,29,52-54 That chronic or serial mIgM engagements may be important to the induction of B-cell apoptosis has also been suggested by other studies. Firstly, Grafton et al5 have recently noted that an anti-IgM MoAb’s ability to induce apoptosis in an early passage Burkitt lymphoma line correlates with the ligand’s capacity to induce a sustained increase in intracellular Ca2+. Secondly, past studies with the murine B-cell line, WEHI-231, had shown that the mIgM-induced cell cycle arrest of these latter lymphoma cells was associated with the length of time during which the cells received signals from anti-Ig.55 56

The compromised capacity of low concentrations of MoAb HB57 to sustain the signals for apoptosis may reflect a lesser capacity of the high-affinity MoAb to continue the process of serial cross-link formation, due to lesser dissociation and reassociation with new receptors once bound. This might prevent many cells from reaching a threshold level of intracellular Ca2+ needed for induction of the apoptotic pathway.5 Additionally, high-affinity MoAb HB57 and intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 may differ in the nature of the cross-links formed at lower ligand concentration, eg, size of clusters, or closed ring configurations versus linear open-ended trains42,57,58 and/or the nature of cross-link-associated events, eg, cytoskeletal association or membrane reorganization.43 59 Such variations might have a greater impact on the sustained signaling for apoptosis than the early signaling for protein tyrosine phosphorylation.

The impaired induction of apoptosis by the relatively high-affinity anti-IgM MoAb XG9 is likely explained by a phenomenon somewhat distinct from that for MoAb HB57. Previous immunoelectron microscopy studies had shown that MoAb XG9 has a propensity for monogamous binding to the dually expressed Cμ1 epitopes on monomeric human IgM,30ie, both Fab binding sites on the anti-Ig MoAb engaged with the two epitopes on a single mIg molecule.42,60 This tendency for monogamous binding is probably favored by the fact that the spacing between the Cμ1 epitopes on mIgM is comparable to the spacing between the Fab combining sites of the Cμ1-specific MoAb. Importantly, a monogamously bound high-affinity ligand is quite stable, ie, has low dissociation.42,60 Thus, MoAb XG9 may less readily re-engage with proximal mIgM receptors to form a cross-link. Interestingly, a number of anti-idiotype (Id) MoAbs have been shown to engage in monogamous binding with Id-expressing Ig.60-62Those anti-Id MoAbs with a high propensity for monogamous binding might be expected to be ineffective at inducing the in vivo apoptosis of malignant B cells as single ligands.

Despite the rapid appearance of annexin-positive cells after Ramos exposure to cross-link–inducing anti-IgM MoAb, ie, within 30 minutes of Ramos exposure to intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53, maximal apoptosis was noted after 24 hours of culture. A likely explanation is that not all Ramos cells are susceptible to apoptosis at a given time. Based on findings with other cells, one might predict that susceptibility to mIgM-triggered growth arrest and apoptosis is strongly affected by stage in the cell cycle.63,64 The rapid response noted in the susceptible population of cells is consistent with induction of the apoptotic pathway after mobilization of a threshold amount of intracellular Ca2+.5 65

It should be noted that the mIg occupancy requirements for transduction of inhibitory signals may differ in distinct populations of malignant B cells. For example, the affinity and concentration requirements for inducing inhibition of DNA synthesis in an in vitro-propagated murine B-cell lymphoma66 and in leukemic cells obtained from the peripheral blood of patients with hairy cell leukemia (HCL)16,30 had been found to be much less demanding than that noted here and elsewhere for induction of a cell cycle block and/or apoptosis in the Burkitt’s B-cell lines, Ramos and Daudi.10,18 The differences in the responses do not appear to reflect gross differences in mIgM density, because the Burkitt B-cell lines and the HCL clonal populations were all characterized by relatively high levels of mIgM. It is possible that the differences represent the relative density or concentration of mIg-associated proteins or intracellular signaling molecules in the various populations. Additionally, given that higher intracellular concentrations of bcl-x have been reported to make cells resistant to anti-IgM–induced apoptosis triggered by low, but not by high avidity binding, the varying binding requisites for growth inhibition in these diverse populations may reflect differences in expression of bcl-x.67

Unlike the present observations with Ramos cells, our studies with normal nontransformed B cells have consistently shown that high-affinity MoAb HB57 is notably more effective than intermediate-affinity MoAb Mu53 at triggering the entry and progression of resting B cells into the cell cycle,19 as well as at triggering early protein tyrosine phosphorylation (unpublished results). The differing effects of ligand:receptor affinity in responses of Ramos B cells and normal B cells may, at least in part, reflect the density of mIgM on the respective cell populations. Most mIgM+ cells in normal human B-cell populations express a lesser density of mIgM than Ramos B cells, and other studies have demonstrated that a decrease in receptor density can increase the ligand:receptor affinity threshold for signal transduction.68-70 Additionally, differing rates of receptor diffusion or differing expression of regulatory molecules could influence the ligand:receptor binding thresholds for signal transduction.

Despite the fact that Burkitt cell lines and normal mature B cells may differ in the optimal conditions for achieving receptor cross-linking, studies in both types of cells suggest that mIg-induced B-cell apoptosis is favored by a high degree of receptor occupancy and extensive receptor cross-linking.8-10,18 The explanation for why less extensive receptor occupancy and cross-linking in normal B cells results in positive signals for proliferation8,19,20 71 remains to be elucidated. Additionally, whether the same also holds for malignant B cells that receive positive signals for growth needs to be further investigated. A greater appreciation of how differing ligand engagement with the B-cell antigen receptor can positively or negatively affect lymphoma growth is important for optimal therapeutic intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr David Holowka for helpful discussions.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. GM-35174 and by a grant from the S.L.E. Foundation, Inc.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Patricia K.A. Mongini, PhD, Department of Rheumatology, Hospital for Joint Diseases, 301 E 17th St, New York, NY 10003.