Abstract

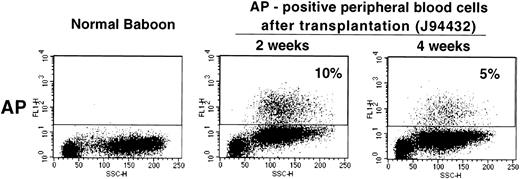

We have used a competitive repopulation assay in baboons to develop improved methods for hematopoietic stem cell transduction and have previously shown increased gene transfer into baboon marrow repopulating cells using a gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV)-pseudotype retroviral vector (Kiem et al, Blood 90:4638, 1997). In this study using GALV-pseudotype vectors, we examined additional variables that have been reported to increase gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor cells in culture for their ability to increase gene transfer into baboon hematopoietic repopulating cells. Baboon marrow was harvested after in vivo administration (priming) of stem cell factor (SCF) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). CD34-enriched marrow cells were divided into two equal fractions to directly compare transduction efficiencies under different gene transfer conditions. Transduction by either incubation with retroviral vectors on CH-296–coated flasks or by cocultivation on vector-producing cells was studied in five animals; in one animal, transduction on CH-296 was compared with transduction on bovine serum albumin (BSA)-coated flasks. The highest level of gene transfer was obtained after 24 hours of prestimulation followed by 48 hours of incubation on CH-296 in vector-containing medium in the presence of multiple hematopoietic growth factors (interleukin-6, stem cell factor, FLT-3 ligand, and megakaryocyte growth and development factor). Using these conditions, up to 20% of peripheral blood and marrow cells contained vector sequences for more than 20 weeks, as determined by both polymerase chain reaction and Southern blot analysis. Gene transfer rates were higher for cells transduced on CH-296 as compared with BSA or cocultivation. In one animal, we have used a vector expressing a cell surface protein (human placental alkaline phosphatase) and have detected 10% and 5% of peripheral blood cells expressing the transduced gene 2 and 4 weeks after transplantation as measured by flow cytometry. In conclusion, the conditions described here have resulted in gene transfer rates that will allow detection of transduced cells by flow cytometry to facilitate the evaluation of gene expression. The levels of gene transfer obtained with these conditions suggest the potential for therapeutic efficacy in diseases affecting the hematopoietic system.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

HEMATOPOIETIC stem cell gene therapy has been considered for a variety of genetic diseases.1-3 Most of these diseases have in common that they can be treated successfully by allogeneic stem cell transplantation. These allogeneic transplantation studies have shown that hematopoietic reconstitution with 100% genetically normal donor cells is not required to cure many genetic diseases, and mixed hematopoietic chimerism with only 10% to 20% of donor cells can correct some genetic disorders.4 In patients with thalassemia, engraftment with only 4% to 7% donor cells can lead to significant clinical improvement.5 Therefore, gene transfer efficiencies between 5% and 20% would be expected to have therapeutic relevance.

A major obstacle to successful stem cell gene therapy has been the low gene transfer efficiencies in human gene therapy trials. Highly efficient gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor cells in culture and in the mouse has been shown using a variety of methods: addition of hematopoietic growth factors, transduction on stromal cells or fibronectin, and physical manipulation to improve vector-cell interaction.6-12 Unfortunately, neither in vitro studies nor studies in the mouse have been able to accurately predict gene transfer efficiency into stem cells of large animals or humans. Recently, growth factor stimulation of marrow or peripheral blood cells has been shown to increase gene transfer rates into hematopoietic stem cells in monkeys.13 However, despite these improvements, gene transfer levels in large animals or humans have remained below 5%, a level that is most likely not clinically relevant.13-17 In this report, we have, therefore, examined a number of manipulations for their ability to improve gene transfer into hematopoietic repopulating cells using our previously described competitive repopulation assay in baboons.15

Our results show high-level gene transfer into granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)/stem cell factor (SCF)–primed marrow repopulating cells after retroviral transduction on CH-296 in the presence of interleukin-6 (IL-6), SCF, FLT-3 ligand (FLT3L), and megakaryocyte growth and development factor (MGDF). The gene transfer efficiencies achieved with this protocol allowed flow cytometric detection of transduced cells in vivo. Furthermore, the conditions described here may allow therapeutically relevant gene transfer levels for human stem cell gene therapy protocols.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Healthy juvenile baboons (Papio cynocephalus cynocephalus orP cynocephalus anubis) were housed at the University of Washington Regional Primate Research Center (Seattle, WA) under conditions approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. Studies were conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board and Animal Care and Use Committees. All animals were provided with water, biscuits, and fruit ad libitum. All procedures, including marrow and blood draws, were performed after animals had been anesthetized with a combination of ketamine-HCl (Aveco, Fort Dodge, IA) and Xylazine (Haver, Shawnee, KS).

Animals were treated with recombinant human (rh)-SCF (50 μg/kg) and rh-G-CSF (100 μg/kg; kindly provided by Dr Ian McNiece, Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) as single daily subcutaneous injections. In the first three animals (T95096, F94424, and T94397), marrow was harvested after 7 days of growth factor administration; in the subsequent animals, marrow was harvested after 5 days of growth factor administration. Marrow (25 to 60 mL) aspirated from the humeri and/or femora was collected in preservative-free heparin.

A central venous catheter, used with a tether system,18 was placed in each animal to allow administration of fluids, prophylactic broad spectrum antibiotics, and transfusions as well as blood draws after transplantation without the need for sedation. Transfusions of irradiated (2,000 to 3,000 cGy) fresh whole blood were used to treat thrombocytopenia and anemia. Animals in the present study received posttransplant G-CSF at 100 μg/kg intravenously once daily, starting at day 0 until their peripheral blood neutrophil counts were greater than 5,000/μL. As preparation for transplantation, all animals received a myeloablative dose (1,020 cGy) of total body irradiation (TBI) administered from opposing 60Cobalt sources at 7 cGy/min as either a single dose or two equal doses (510 cGy) 24 hours apart.

Retrovirus vectors.

The LN, LNX, and LNL615,19 vectors carry the bacterial neomycin phosphotransferase (neo) gene conferring G418 resistance and are identical with the exception of different length sequences between the neo gene and the 3′ vector long terminal repeat (LTR). As such, a single pair of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers can be used to amplify different length sequences, thereby distinguishing cells genetically marked by the different vectors. Vector stocks were made using PG13 retrovirus packaging cells.20 Individual producer cell clones with equal titers were selected for the LN/LNX comparisons. Vector titers were 5 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL on D17 and HeLa cells. To confirm that vectors performed similarly in vivo, we transplanted one baboon with equal numbers of primed CD34-enriched cells transduced by the two different vectors, LN (PG13) and LNX (PG13). Gene transfer efficiency in peripheral blood cells was similar between the two different vectors (data not shown). Unfortunately, the animal died 6 weeks after transplant and, therefore, no long-term follow-up is available. The LAPSN vector carries a gene encoding human placental alkaline phosphatase in addition to the neo gene and has been described.21

Gene transfer into baboon CD34-enriched cells.

Bone marrow (BM) buffy coat cells were labeled with IgM monoclonal antibody 12-8 (CD34) at 4°C for 30 minutes, washed, incubated with rat monoclonal antimouse IgM microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed, and then separated using an immunomagnetic column technique (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity of the CD34-enriched cells was between 83% and 97%.

In the first three animals (T95096, F94424, and T94397), we compared 48-hour cocultivation on vector-producing cells with 48-hour transduction on CH-296 coated flasks in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF. Protamine sulfate (8 μg/mL) was added to all cocultivations but only to the transduction on CH-296 in the third animal (T94397). In the following two animals, J95009 and T94433, we added a 24-hour prestimulation step, and we changed the growth factor cocktail to IL-6, SCF, FL3L, and MGDF for the transduction over CH-296. In both animals, cocultivation on vector-producing cells was performed over 72 hours in the presence of protamine sulfate and IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (J95009) or IL-6, SCF, FL3L, and MGDF (T94433). In the sixth animal, M94123, we compared transduction on CH-296 directly with transduction on bovine serum albumin (BSA) in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF.

Equal numbers of CD34-enriched cells were either placed into 75-cm2 canted-neck flasks (Corning, Corning, NY) that had been seeded 6 to 8 hours earlier with packaging cells or into flasks that were coated with CH-296 (RetroNectin; Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan) at 10 μg/cm2, as described.12,22 23 Cells were cultured for 48 to 72 hours in 30 mL of a 2:1 mix of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY) in the presence of 50 ng/mL each of recombinant human SCF, IL-3, IL-6 or IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF with or without 8 μg/mL protamine sulfate. DMEM contained 4.5 g/L glucose plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium was supplemented with 12.5% horse serum (GIBCO-BRL), 12.5% FBS (GIBCO-BRL), 10−6 mol/L hydrocortisone (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO), 0.1 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 1% glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO-BRL). For cells transduced in flasks coated with CH-296, fresh retrovirus-containing medium was added four times over a period of 48 hours. Except for the first two animals (J95096 and F94424), protamine sulfate was added at 8 μg/mL. After transduction, nonadherent and adherent cells (including packaging cells) collected from the cultures were infused into the same animals from which the cells were obtained after the animals had received a myeloablative dose of TBI.

Analysis of neo gene expression by colony-forming unit-culture (CFU-C) assay.

CD34-enriched cells (1,000 to 5,000 per 35-mm plate) were cultured in a double-layer agar culture system as previously described.24Briefly, isolated cells were cultured in α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 25% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 0.1% BSA (fraction V; Sigma), and 0.3% (wt/vol) agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) overlaid on medium with 0.5% agar (wt/vol) containing 100 ng/mL of SCF, IL-3, IL-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), G-CSF, and 4 U/mL erythropoietin (Epo; provided by Dr Ian McNiece). Cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% air in a humidified incubator. All cultures were performed in triplicate. Colonies grown with and without G418 (1 to 3 mg/mL of active drug) were enumerated at day 14 of culture using an inverted microscope. Untransduced control cells were plated at the same time with the same G418 concentrations. Only G418 concentrations that did not result in any breakthrough colonies in the untransduced controls were used to enumerate the transduced G418-resistant colonies. Positive colonies were picked after 10 to 14 days and DNA was prepared from colonies as described.15

Expression of human placental alkaline phosphatase.

Alkaline phosphatase histochemical staining has been described.25 Briefly, cells were fixed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% glutaraldehyde for 15 minutes, washed twice in PBS, and incubated at 65°C for 30 minutes to eliminate endogenous alkaline phosphatase (AP). For AP staining, cells were incubated overnight at room temperature in 100 mmol/L Tris (pH 8.5), 100 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mg of nitroblue tetrazolium per milliliter, and 0.1 mg of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolphosphate per milliliter. For flow cyctometric analysis, transduced cells were labeled using the anti-AP antibody, 8B6, or an isotype-matched control IgG2a (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) and goat antimouse IgG2a-FITC (Caltag, San Francisco, CA). Stained cells were analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Viability was determined by propidium iodide staining.

PCR analysis posttransplant.

Genomic DNA was prepared using DNAzol (MRC Inc, Cincinnati, OH). Amplification conditions for LN and LNX vectors have been described.15 Briefly, between 50 and 500 ng (depending on signal intensities) of genomic DNA was amplified with either LN/LNL6 2229 and LN/LNL6 3210 or with neo 350 and neo 1150 using 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT). Conditions were optimized to ensure linear amplification in the range of the intensity of the positive PCR samples: denaturation at 95°C, followed by 31 cycles of 62°C annealing (1 minute), and 95°C denaturation (1 minute), with a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. For the detection of LN and LNX, PCR was performed in the presence of 10 μCi/mL 32P deoxycytidine triphosphate and products were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. To standardize DNA concentrations between samples, PCR amplification of the β-actin gene was performed using 100 ng of genomic DNA and the following primers: actin-1 5′ TCC TGT GGC ATC CAC GAA ACT 3′ and actin-2 5′ GAA GCA TTT GCG GTG GAC GAT 3′. Conditions for β-actin PCR were the same as for the neo gene, except that only 16 cycles were used. For the analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations, T and B cells were sorted using CD20 (Becton Dickinson) and CD4 and CD8 (Becton Dickinson) antibodies. Cell pellets of 10,000 cells were then analyzed by PCR using conditions similar to those described for CFU-C colonies. Phosphorimage analysis was used to quantitate PCR signal intensities by comparing PCR signals in blood and marrow posttransplant with PCR signals in a log dilution series of single-vector copy HT1080/LN and HT1080/LNX cellular DNA mixed at a 1:1 ratio. HT1080 cells (ATCC, CCL-121) are human fibrosarcoma cells. The gene transfer percentages obtained with this method assume that the peripheral blood or marrow cells that are marked with a vector contain no more than one copy of the vector per cell.

Southern blot analysis posttransplant.

Genomic DNA was restricted with either Xba I or withSac I and HindIII. Restriction by Xba I shows full-length integrated retroviral DNA only. Restriction by SacI and HindIII differentiates between LN and LNX. LNX has aHindIII site and LN does not.

Detection of helper virus.

After transplantation, peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNA was assayed for recombinant helper virus genomes by PCR using the above-described amplification conditions for neo. Positive control log dilutions of DNA from PG13/LN packaging cells into normal baboon DNA were run concurrently. The sequence of the primers used to amplify the gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV) envelope gene has been described.15 PCR analysis of peripheral blood samples for the presence of GALV envelope sequences was negative in all animals, indicating that there was no helper-virus infection present.

RESULTS

Engraftment in baboons transplanted with transduced primed CD34-enriched marrow cells.

Five baboons were transplanted with transduced CD34-enriched autologous marrow cells isolated from G-CSF/SCF primed baboons to compare gene transfer efficiency between cocultivation on vector-producing packaging cells and transduction on CH-296–coated flasks with virus-containing medium (VCM) in the absence of packaging cells (Table 1). In a sixth animal, transduction on CH-296 was directly compared with transduction on BSA-coated flasks. All animals received similar numbers of CD34-enriched cells from the two different transduction procedures (mean, 6.0 × 106 cells/kg). An average of 13.5 days was required to achieve an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of greater than 500/μL. One animal (F94424) died of infectious complications 1 month after transplantation. Gene transfer efficiencies in CFU-C assayed at the end of transduction but before infusion are shown in Table 2. After transplantation, DNA from peripheral blood and marrow was analyzed for the presence of the LN (transduction on CH-296) and LNX (cocultivation or transduction on BSA) vector sequences.

Comparison between cocultivation and transduction on CH-296 in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF without prestimulation.

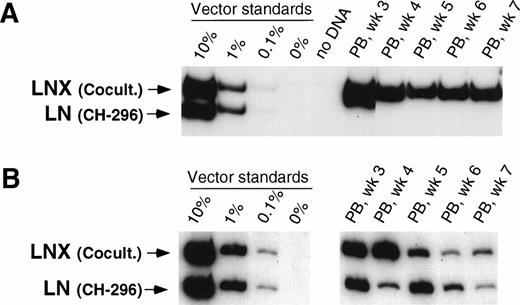

In our initial three animals, we directly compared 48-hour transduction with VCM on CH-296 with our previously published transduction procedure involving 48-hour cocultivation with vector-producing packaging cells in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF.15 In two animals (T95096 and F94424), gene transfer was higher with cocultivation as compared with transduction on CH-296 as measured by CFU-C before infusion of transduced cells as well as posttransplant. Overall, transduction in these two animals was between 1% and 10% for LNX (cocultivation) and below 0.1% for LN (transduction on CH-296). Figure 1A shows results from one of the two animals. In animal T94397 (Fig 1B), the gene transfer rate in CFU-C was higher for transduction on CH-296, and posttransplant samples showed gene transfer rates between 0.1% and 1% for both the LN and LNX vector sequences, indicating similar gene transfer into repopulating cells (Fig 1B). A 48-hour transduction on CH-296 in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF, therefore, seemed to offer no discernible advantage over cocultivation on vector-producing cells.

Detection of vector sequences in peripheral blood from baboons T95096 (A) and T94397 (B). Animals were transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 48 hours of cocultivation (LNX) or on CH-296 (LN) in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF without protamine sulfate (A) and with protamine sulfate (B). PCR was performed to quantitate LNX and LN vector amounts. LNX versus LN. Standards consist of single-vector copy HT1080/LN and HT1080/LNX DNA mixed at a 1:1 ratio and then mixed with normal baboon DNA in a log dilution series. PB, peripheral blood.

Detection of vector sequences in peripheral blood from baboons T95096 (A) and T94397 (B). Animals were transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 48 hours of cocultivation (LNX) or on CH-296 (LN) in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF without protamine sulfate (A) and with protamine sulfate (B). PCR was performed to quantitate LNX and LN vector amounts. LNX versus LN. Standards consist of single-vector copy HT1080/LN and HT1080/LNX DNA mixed at a 1:1 ratio and then mixed with normal baboon DNA in a log dilution series. PB, peripheral blood.

Comparison between cocultivation and transduction on CH-296 in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF with prestimulation.

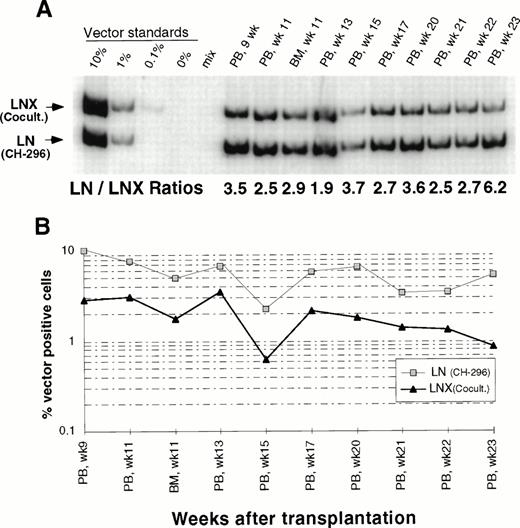

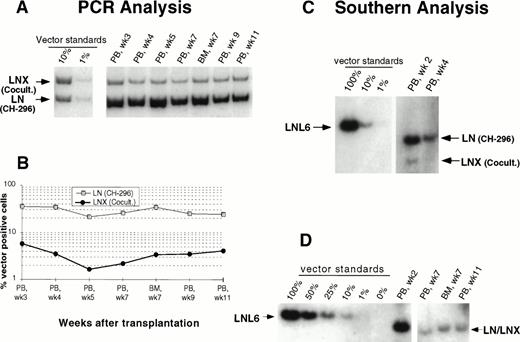

In an attempt to improve gene transfer rates, we added a 24-hour prestimulation with IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF to our transduction protocol using CH-296. In both subsequent animals (J95009 and T94433), transductions on CH-296 were performed with prestimulated cells in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. Transduction by cocultivation was performed over 72 hours in the presence of protamine sulfate and IL-3, IL-6, and SCF (J95009) or IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF (T94433). In both animals, transduction on CH-296 led to higher gene transfer rates in peripheral blood and marrow samples posttransplant than transduction by cocultivation (Figs2, 3, and4). PCR results were confirmed by Southern blot analysis and showed gene transfer rates of up to 20% in T94433 using CH-296, protamine sulfate, and growth factors IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF for more than 20 weeks (Fig 4). In this animal, we have also sorted CD2+ T cells and CD20+ B cells, and DNA from these cell populations showed similarly high gene transfer rates (Fig 4).

Detection of vector sequences in peripheral blood from baboon J95009 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of cocultivation (LNX) in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF or over CH-296 (LN) in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences, LNX versus LN. Standards consist of single-vector copy HT1080/LN and HT1080/LNX DNA mixed at a 1:1 ratio and then mixed with normal baboon DNA in a log dilution series. PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphorimage analysis of signal intensities for LN (301 bp) and LNX (326 bp) corrected for the amount of DNA as determined by actin PCR.

Detection of vector sequences in peripheral blood from baboon J95009 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of cocultivation (LNX) in the presence of IL-3, IL-6, and SCF or over CH-296 (LN) in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences, LNX versus LN. Standards consist of single-vector copy HT1080/LN and HT1080/LNX DNA mixed at a 1:1 ratio and then mixed with normal baboon DNA in a log dilution series. PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphorimage analysis of signal intensities for LN (301 bp) and LNX (326 bp) corrected for the amount of DNA as determined by actin PCR.

Detection of vector sequences in peripheral blood and marrow from baboon T94433 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of cocultivation (LNX) or over CH-296 (LN) both in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences, LNX versus LN. PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphorimage analysis of signal intensities for LN and LNX corrected for the amount of DNA as determined by actin PCR. (C) Southern blot analysis for the presence of vector sequences in DNA from peripheral blood. DNA was restricted with Sac I, which cuts both vectors outside the neo gene, and HindIII, which cuts the LNX vector only. The resulting fragments were 3,052 bp (LNL6), 2,370 bp (LN), and 1,932 bp and 464 bp (LNX). (D) Southern blot analysis of DNA from PB and BM restricted with Xba I, which cuts the vectors once in the LTR and therefore results in the full-length vector fragment only of integrated retrovirus. The respective fragments are 3,049 bp (LNL6), 2,369 bp (LN), and 2,394 bp (LNX). LN/LNX, both vectors are detected at the same place on the gel.

Detection of vector sequences in peripheral blood and marrow from baboon T94433 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of cocultivation (LNX) or over CH-296 (LN) both in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences, LNX versus LN. PB, peripheral blood; BM, bone marrow. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphorimage analysis of signal intensities for LN and LNX corrected for the amount of DNA as determined by actin PCR. (C) Southern blot analysis for the presence of vector sequences in DNA from peripheral blood. DNA was restricted with Sac I, which cuts both vectors outside the neo gene, and HindIII, which cuts the LNX vector only. The resulting fragments were 3,052 bp (LNL6), 2,370 bp (LN), and 1,932 bp and 464 bp (LNX). (D) Southern blot analysis of DNA from PB and BM restricted with Xba I, which cuts the vectors once in the LTR and therefore results in the full-length vector fragment only of integrated retrovirus. The respective fragments are 3,049 bp (LNL6), 2,369 bp (LN), and 2,394 bp (LNX). LN/LNX, both vectors are detected at the same place on the gel.

Detection of vector sequences in PB from baboon T94433 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of cocultivation (LNX) or over CH-296 (LN) both in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences, LNX versus LN. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphorimage analysis of signal intensities for LN and LNX corrected for the amount of DNA as determined by actin PCR. (C) PCR analysis of T and B cells 12 and 16 weeks after transplantation. (D) Southern blot analysis of DNA from peripheral blood restricted withXba I, which cuts the plasmid forms of the vectors once in the 3’ LTR and cuts the integrated forms of the vectors once in each LTR, thus resulting in production of full-length vector fragment only from integrated vector. The respective fragment sizes are 2,369 bp (LN) and 2,394 bp (LNX).

Detection of vector sequences in PB from baboon T94433 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of cocultivation (LNX) or over CH-296 (LN) both in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, MGDF, and protamine sulfate. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences, LNX versus LN. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphorimage analysis of signal intensities for LN and LNX corrected for the amount of DNA as determined by actin PCR. (C) PCR analysis of T and B cells 12 and 16 weeks after transplantation. (D) Southern blot analysis of DNA from peripheral blood restricted withXba I, which cuts the plasmid forms of the vectors once in the 3’ LTR and cuts the integrated forms of the vectors once in each LTR, thus resulting in production of full-length vector fragment only from integrated vector. The respective fragment sizes are 2,369 bp (LN) and 2,394 bp (LNX).

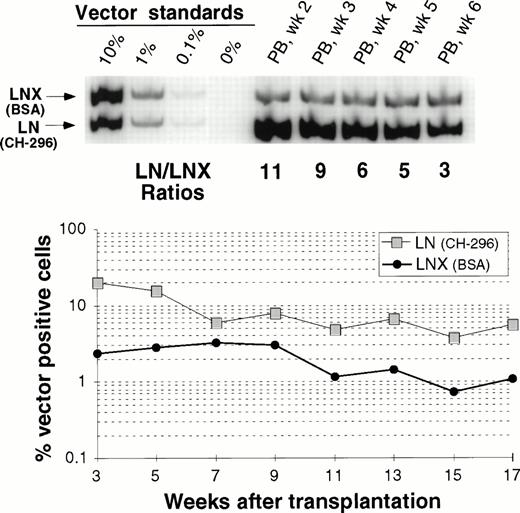

Comparison between transduction of prestimulated cells on CH-296 or on BSA in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF.

In one animal we have directly compared gene transfer rates between transduction on CH-296 and transduction on BSA. Figure 5 shows peripheral blood analysis up to 17 weeks after transplantation. In all samples analyzed, gene-marking levels with LN (CH-296) were higher than marking levels with LNX (BSA). This difference was more pronounced early after engraftment, suggesting a greater impact of CH-296 on progenitor cells than on long-term repopulating cells. However, at 17 weeks, the gene transfer rates were still about fivefold higher with CH-296 compared with BSA.

Detection of vector sequences in PB from baboon M94123 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of transduction on BSA (LNX) or on CH-296 (LN) in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences early after transplantation. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphor image analysis after transplantation.

Detection of vector sequences in PB from baboon M94123 transplanted with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced by 72 hours of transduction on BSA (LNX) or on CH-296 (LN) in the presence of IL-6, SCF, FLT3L, and MGDF. (A) PCR analysis of amplified vector sequences early after transplantation. (B) Percentage of vector-positive DNA measured by phosphor image analysis after transplantation.

Analysis of in vivo gene transfer efficiency by flow cytometry.

Given the relatively high gene transfer rates obtained with our transduction protocol, we next studied whether a vector containing a gene encoding a cell surface protein could be used in the baboon to measure gene transfer and gene expression levels in vivo. We used the LAPSN vector that expresses a human placental alkaline phosphatase gene, which can be detected both histochemically and by flow cytometry, in addition to the neo gene. One animal, for which short-term follow-up data are available, has been transplanted with CD34+ cells isolated from primed marrow that were transduced using the culture conditions described in the previous section. At the time of transplantation, 11% of the CFU-C was both G418 resistant and expressed AP as determined by histochemical staining. At 2 and 4 weeks after transplantation 10% and 5%, respectively, of peripheral blood cells expressed AP, as detected by flow cytometry (Fig 6). Therefore, the culture conditions described can result in sufficiently high gene transfer rates in vivo that transduced cells can be assayed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood cells in a normal baboon and in J94432 after transplantation with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced with a retroviral vector containing the human placental alkaline phosphatase gene (LAPSN). The percentage of live-gated cells that expressed human placental alkaline phosphatase is indicated.

Flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood cells in a normal baboon and in J94432 after transplantation with CD34-enriched marrow cells transduced with a retroviral vector containing the human placental alkaline phosphatase gene (LAPSN). The percentage of live-gated cells that expressed human placental alkaline phosphatase is indicated.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown improved gene transfer into hematopoietic progenitor cells in humans and into baboon marrow repopulating cells using a GALV-pseudotype vector.26 The baboon study used cocultivation on vector-producing packaging cells for transduction of hematopoietic repopulating cells, a method that has not been approved for human gene therapy due to concerns over infusion of murine vector-producng cells. In this study, we have therefore used a competitive repopulation assay in baboons to examine the use of CH-296 in combination with a number of other factors for the ability to improve transduction of CD34+ marrow repopulating cells in a clinically applicable protocol.

In our initial experiments involving transduction of marrow cells on CH-296, we used a growth factor combination (IL-3, IL-6, and SCF) that had provided relatively efficient gene transfer in our previous study using cocultivation on vector-producing cells.15 In the presence of these cytokines, 48-hour cocultivation resulted in better gene transfer into CFU-C before infusion of cells and in baboons posttransplant than 48-hour incubation with four vector exchanges on CH-296 without protamine sulfate. In one animal (T94397), protamine sulfate was added during the 48-hour transduction on CH-296, and in this animal gene transfer efficiency in vivo was similar between cocultivation and transduction on CH-296. Based on these results, we added protamine sulfate to transductions of cells on CH-296 in subsequent animals. Overall, gene transfer on CH-296 was less than 1% in all three animals. Low gene transfer rates on CH-296 have also been reported for human hematopoietic progenitors when cells were not prestimulated or when cultured in the absence of growth factors.23

To improve gene transfer to cells cultured on CH-296, we included a 24-hour prestimulation step and added FLT3L and MGDF. Based on studies in the mouse by Yonemura et al27 showing that IL-3 may interfere with the reconstituting ability of hematopoietic stem cells, we also eliminated IL-3 from our growth factor cocktail. These conditions gave us the best gene transfer rates in vivo (up to 20%). However, because we changed more than one variable in these animals (growth factor cocktail and the addition of a 24-hour prestimulation), it is unclear how much the improved gene transfer rates were due to the alteration in growth factors and how much to the prestimulation. Using these conditions, gene transfer into baboon repopulating cells was better with CH-296 as compared with cocultivation and also compared with transduction on BSA only.

Administration of G-CSF in combination with SCF has been shown to increase the number of hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells in the peripheral blood of baboons and dogs.28,29 Growth factor administration before harvesting of hematopoietic cells has also been shown to improve gene transfer into hematopoietic cells in culture30 and also in monkeys.13 Dunbar et al13 harvested marrow 14 days after discontinuation of G-CSF and SCF and compared results to steady-state marrow in two animals. In both animals, gene transfer into early repopulating cells was better with primed marrow; however, after 6 months, that difference was only seen in one of the animals. Based on our observation that baboons treated with G-CSF and SCF for 7 days had an expansion of morphologically immature progenitors in the marrow,31,32 we have used marrow cells harvested after 5 or 7 days of growth factor administration. Compared with our previously published animals that were transplanted with unprimed marrow cells, the overall gene transfer efficiency in the animals in this study using primed marrow cells was higher (data not shown). Recent data have suggested that marrow cells harvested after 5 days of growth factor administration may have reduced ability for long-term repopulation.33 34 However, we have not observed a significant decrease in transduced cells after the first 4 to 5 weeks after transplantation. Further studies will be necessary to determine optimal priming conditions for retrovirus-mediated gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells.

Using the above-described gene transfer conditions and a vector expressing a cell surface protein (LAPSN), we were able to use flow cytometry to evaluate gene transfer in the peripheral blood cells of reconstituted animals. This will now allow us to better follow marked cells in vivo, to evaluate tissue-specific expression, and to preselect transduced cells before infusion similar to studies in the mouse.35

In summary, we have developed conditions that allow high-level gene transfer into hematopoietic repopulating cells in a clinically applicable protocol. The levels of gene transfer obtained with this protocol may allow therapeutically relevant gene expression for the treatment of diseases affecting the hematopoietic system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Mike Gough, Gary Millen, and the staff of the University of Washington Regional Primate Research Center and the staff of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Clinical Hematology laboratory for their assistance. We also acknowledge the assistance of Bonnie Larson and Harriet Childs in preparing the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants and Contracts No. P50 HL54881, P30 CA15704, N01 AI35191, NIHRR00166, and P30 DK47754. J.E.J.R. is supported by the Cancer Research Fund of the Damon Runyon-Walter Winchell Foundation. H.P.K. is a Markey Molecular Medicine Investigator.

Address reprint requests to Hans-Peter Kiem, MD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave N, D1-100, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; e-mail: hkiem@fhcrc.org.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.