Abstract

The effect of folate status on the efficacy and toxicity of chemotherapy was investigated in weanling Fischer 344 rats maintained on diets of varying folate content or supplemented with daily injections of folic acid, 50 mg/kg, for 6 to 7 weeks. MADB106 rat mammary tumor growth rate was the same in folate replete and supplemented rats, but retarded in the low folate groups. The tumor growth inhibitions in low folate, replete and high folate rats treated with cyclophosphamide were: 53%, 98%, and 97% (P = .048); with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU): 46%, 49%, and 66%; and with doxorubicin: 25%, 55%, and 61%. Significant differences in survival were observed for cyclophosphamide (P = .0084) and 5-FU (P = .025) related to dietary folate content. Thus, folate deficiency impedes tumor growth rate, but supplementation does not accelerate it in folate replete animals. Correction of folate deficiency approximately doubles the efficacy of cyclophosphamide in rats with much less host toxicity. Folate repletion improves survival in 5-FU–treated animals. These studies indicate that nutritional folate status has an important influence on the efficacy and toxicity of some commonly used cancer chemotherapeutic drugs.

FOLIC ACID DEFICIENCY has been observed in patients with cancer due to the combination of inadequate dietary folacin content, poor dietary intake, and the increased metabolic needs imposed by malignancy.1 For example, Magnus2reported that in a series of patients with metastatic cancer, 85% had abnormally low serum folate levels and 16% had low red blood cell folate levels. Clamon et al,3 in a study of lung cancer patients, noted that 36.7% of patients with limited stage disease, 38.5% of patients with hepatic metastases, and 47.1% of patients who had lost more than 9% of body weight had reduced serum folate levels. However, clinicians are uncertain about the management of folic acid deficiency in patients with cancer. In 1948, Farber et al4 described acceleration of the leukemic processes by folic acid conjugates to a degree not encountered in other children with acute leukemia, and Heinle and Welch5reported that administration of folic acid to three patients with chronic myeloid leukemia was attended by rapid hematologic and clinical relapse in each case. Subsequent studies in rodents confirmed that dietary restriction of folic acid inhibited the growth of tumors. Rosen and Nichol6 reported that when rats were placed on a folate-deficient diet 2 weeks before transplantation of Walker carcinosarcoma 256, tumor growth was inhibited by 95% on the 28th day after transplantation. The tumor remained viable and resumed rapid growth when folate was added to the diet.6 Potter and Briggs7 similarly found that dietary folate deficiency in mice retarded the growth of ascites tumor cells of lymphocytic neoplasms. An attempt to extend these animal studies to humans by placing seven patients with advanced malignancies on a folate-deficient diet for periods ranging from 25 to 140 days was unsuccessful, as no antitumor effect was noted.8 Nevertheless, clinicians generally have been reluctant to administer folic acid to deficient cancer patients on the chance that the vitamin might accelerate the growth of the malignancy.

Recently, folic acid deficiency during early pregnancy has been associated with birth defects. Consequently the Food and Drug Administration has proposed that the diet of all Americans be fortified with 140 μg of folic acid per 100 g of cereal-grain product.9 The effect of this dietary supplementation with folic acid on cancer patients is unclear, but of concern. The influence of subnormal or supranormal levels of folic acid on the efficacy and toxicity of chemotherapy has received relatively little attention, despite the fact that substantial numbers of patients with cancer are likely to have a nutritional abnormality of folate metabolism or are taking supplemental vitamins, often in megadoses.10Therefore, the studies described herein were designed to investigate the interaction of nutritional folate status and response to chemotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Weanling female Fischer 344 rats (weighing approximately 60 g) were obtained from Charles River Canada (St-Constant, Quebec). The rats were maintained in groups of three or four for 10 days and fed standard rat chow (Teklad 7012; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI). Then rats were housed individually in stainless steel wire-bottomed cages. Their diets were either folate replete (AIN-93G Purified Rodent Diet with Vitamin Free Casein containing 2 mg folic acid/kg of diet), low folate (AIN-93G with vitamin mix lacking folic acid), or very low folate (AIN-93G with vitamin mix lacking folic acid and with 1% succinyl sulfathiazole), all obtained from Dyets, Inc (Bethlehem, PA). At the completion of the study, the rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg intraperitoneally [IP]) and exsanguinated by cardiac puncture. Samples were collected for subsequent folate analyses using previously described methods.11 12 Approximately two thirds of blood removed was allowed to clot at room temperature, the serum was then separated by centrifugation and frozen in 100 μL aliquots at −70°C. The remaining one third was added into a tube containing EDTA to prevent clotting, diluted 1:9 with distilled water containing 1% ascorbic acid, and frozen at −70°C in 1-mL aliquots. The liver was weighed and 1 g homogenized in 3 vol 140 mmol KCl/L. The homogenate was then diluted 1:9 with 50 mmol potassium phosphate/L, pH 4.8, containing 1% ascorbic acid, and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C to allow endogenous conjugase to convert folate polyglutamates to monoglutamates. Afterwards, the homogenates were autoclaved, cooled on ice, and centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 minutes. The supernatants were frozen in three 1-mL aliqouts at −70°C. All animal protocols and care were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Vermont.

Folate assay.

The tissue folate levels were measured on the aformentioned frozen samples by an assay that uses a bacteria that grows only in the presence of folate.13,14 The growth turbidity ofLactobacillus casei (L casei), which grows in proportion to the amount of folic acid present, was measured in a 96-well plate on a microplate reader.13 A standard curve ranging from 0.0625 to 2 ng/well was made using folinic acid, as it is more stable than folic acid.13 Tissue samples were diluted as needed to fit within the parameters of the standard curve. The standard curve, as well as the samples, were diluted in Sorenson's phosphate buffer with 1 mg/mL of ascorbic acid, pH 6.3.13Double strength maintenance media (DIFCO, Detroit, MI) with .5 mg/mL ascorbic acid was added to each plate at 150 μL/well. The ascorbic acid was added to double strength maintenance medium and Sorenson's buffer and filter sterilized just before plating. L casei was diluted 7:1 with Sorenson's phosphate buffer and added at a concentration of 80 μL/well. The addition of 80 μL/well of either sample, folate for the standard curve, or blank diluent brought the total volume to 310 μL/well. The plates were read at a wavelength of 595 nm at 24 hours and sample concentrations were determined by linear regression.

Tumor cell line.

The MADB106 rat mammary tumor cell line (obtained from Dr John Holcenburg, Department of Surgery, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA) was initially developed by IP injections of 7,12-diemethylbenz[α]anthracene into Fischer rats. Tumor was excised and minced. Tumor cells were separated from tumor stroma and injected into the right hind flank of the rats. Tumors were measured at two perpendicular planes using a tissue caliper. Tumor volumes were calculated from the formula: TV = 4/3 πr3 where r = (diameter 1 + diameter 2)/4. Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) was calculated: TGI = 1 − Tvtreatment/TVcontrol × 100.

Statistical methods.

Analysis of variance was used to test the significance of differences in hematocrit levels, rat weights, blood, tumor and liver folate levels, and the efficacy of chemotherapy as influenced by folate status. If a significant F value was found, Fisher's least significant difference test was used to compare means. Tumor size and day were transformed with a natural log function. Hierarchical linear modeling procedures were used to examine the data.15 At the first stage, each rat gave rise to a linear regression line between Log (Tumor Size) and Log (Day) with an intercept and slope. At the second stage, these intercepts and slopes were examined as a function of the four diet groups. The slopes of the linear regression lines were compared using a Fisher protected t type approach.15 Rat survival in the toxicity study was analyzed by the Log-Rank test.

RESULTS

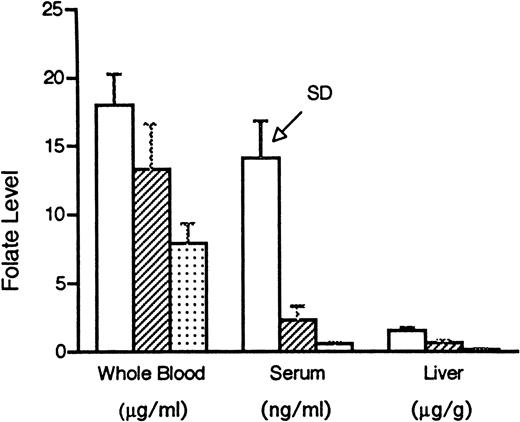

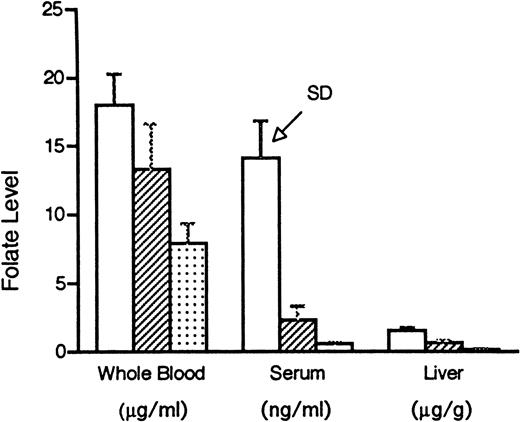

Our intent in these experiments was to study a range of folate status in mammals, but to avoid extreme folate deficiency and thereby more closely approximate the typical clinical situation. Rats maintained for 6 weeks on the folate replete diet, the low folate diet, the very low folate diet, or the folate replete diet supplemented with folic acid, 50 mg/kg dissolved in 8.4% sodium bicarbonate solution and injected IP daily, grew at the same rate (the mean weights of the groups were within 2 g of each other on day 42) and were not anemic, but developed evidence of progressively severe tissue deficiency of the vitamin (Fig 1). There was a significant difference among the three dietary groups (P ≤ .005) for all three tissues, except between low folate and very low folate serum samples (P = .07).

Folate levels, as determined by the L caseimethod, in whole blood, serum, and liver in rats maintained for 6 weeks on a folate replete diet containing 2 mg/kg folic acid (□), a low folate diet containing no folate (▨), or a very low folate diet consisting of no folate plus 1% succinyl sulfathiazole (▧). There was a significant difference (P ≤ .005) among the three dietary groups for all three tissues, except between low folate and very low folate serum samples (P = .07). SD, standard deviation.

Folate levels, as determined by the L caseimethod, in whole blood, serum, and liver in rats maintained for 6 weeks on a folate replete diet containing 2 mg/kg folic acid (□), a low folate diet containing no folate (▨), or a very low folate diet consisting of no folate plus 1% succinyl sulfathiazole (▧). There was a significant difference (P ≤ .005) among the three dietary groups for all three tissues, except between low folate and very low folate serum samples (P = .07). SD, standard deviation.

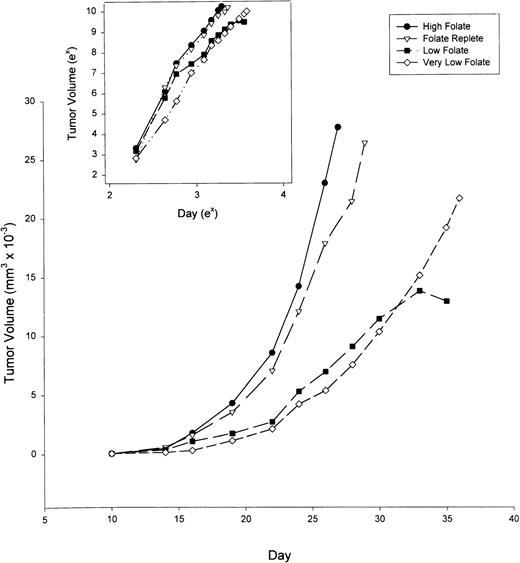

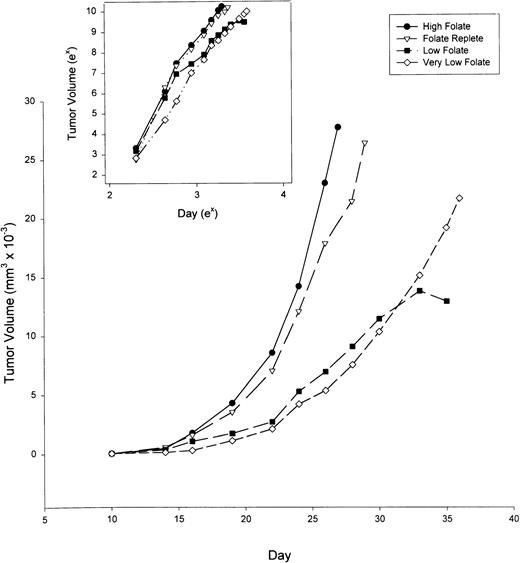

After 6 weeks on the special diets described above, the four groups of six animals each were inoculated subcutaneously with MADB106 rat mammary tumor (1 × 105 viable cells in a 0.2-mL suspension). The rats were examined daily and, when palpable, the tumors were measured in 2 dimensions. Figure 2 shows that tumor growth rate slowed progressively with decreasing amounts of folate intake. Comparison of the slopes of the linear regression line between Log (Tumor Volume) and Log (Day) showed that the rate of tumor growth over time is diet-dependent (P < .05), and that folate supplementation, even at the high levels used in these experiments, did not significantly increase tumor growth rate compared with tumors in folate replete rats (inset, Fig 2). However, folate deficiency of moderate or marked degree significantly retarded the tumor growth rate compared with folate replete or supplemented animals.

Growth of MADB106 mammary tumor in rats maintained on diets of varying folate content. After 6 weeks on the dietary conditions indicated, tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into six animals per group. Tumor volumes were measured by calipers. Insert: Tumor volume and day plotted on natural log scales. At a significance level of 5%, the slopes for the high folate diet were larger than the low and very low folate diets, but not the folate replete diet. The slopes for the folate replete diet were larger than the low folate diet, but not the very low folate diet. The slopes for the very low folate diet were larger than the low folate diet as a group.

Growth of MADB106 mammary tumor in rats maintained on diets of varying folate content. After 6 weeks on the dietary conditions indicated, tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into six animals per group. Tumor volumes were measured by calipers. Insert: Tumor volume and day plotted on natural log scales. At a significance level of 5%, the slopes for the high folate diet were larger than the low and very low folate diets, but not the folate replete diet. The slopes for the folate replete diet were larger than the low folate diet, but not the very low folate diet. The slopes for the very low folate diet were larger than the low folate diet as a group.

The folate levels in the tumors and livers from animals in the different folate groups are shown in Table1. Both tumor and liver folate levels progressively decreased with decreasing dietary folate intake, but liver folate was higher than tumor folate in each dietary group. All tumor folate levels were significantly different from each other, at P ≤ .05, except for the low folate versus very low folate groups. Similarly the differences between hepatic folate levels were significant (P≤ .02) except for the low folate versus very low folate groups. The tumor and liver folate levels were correlated, withr2 = 0.93, P < .05.

Histologic examination of the tumors from the different folate groups showed poorly differentiated carcinoma, with abundent necrosis, and variable numbers of mitotic figures. There was no evidence of megaloblastosis. No pathologic distinction could be discerned among tumors differing in folate status.

To investigate the effect of folate status on the efficacy of chemotherapy, weanling Fischer 344 rats were divided into three groups of six animals each and maintained on a low folate diet, a folate replete diet, or the latter diet supplemented with folic acid, 50 mg/kg IP daily. After 7 weeks, MADB106 Mammary Tumor was injected subcutaneously (5 × 105 cells/0.5 mL). When tumor was palpable, the rats received cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg, doxorubicin 5 mg/kg, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 50 mg/kg, or 0.9% NaCl solution IP. The planned course of treatment was to repeat the same medications 4 and 8 days later. However, we found that the folate-deficient rats were much more sensitive to the side effects of chemotherapy. After only two of the planned three treatments, the condition of the animals in this group rapidly deteriorated and the third treatment was not given. Of the folate-deficient animals treated with two doses of cyclophosphamide, two of six died (33% mortality). In contrast, there was a 33% mortality after three courses of cyclophosphamide in the folate-replete group, but no mortality in the folate-supplemented rats treated with three injections of cyclophosphamide. After three injections of 5-FU, there was one death in the folate-supplemented group (17% mortality), but none in the folate-deficient or replete dietary groups. There were no deaths among the three dietary groups treated with doxorubicin.

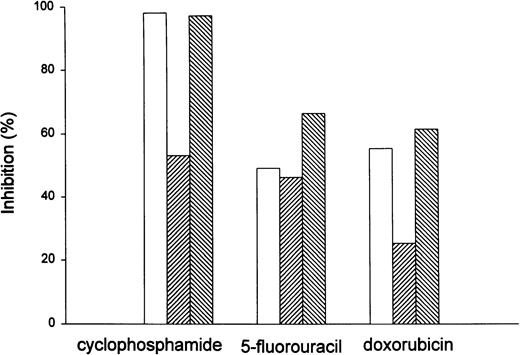

To compare the efficacy of chemotherapy under different dietary conditions, tumor inhibition as a percentage of control (0.9% NaCl solution-injected rats) was calculated 96 hours after the second injection of chemotherapy (just before the scheduled third injection). Figure 3 shows that the TGIs for cyclophosphamide were 53%, 98%, and 97% in the low folate, replete, and high folate rats, respectively. For 5-FU, the TGIs were 46%, 49%, and 66%, and for doxorubicin the TGIs were 25%, 55%, and 61%, respectively. Using analysis of variance, the difference between the folate-deficient animals treated with cyclophosphamide and the folate-replete or supplemented rats was significant (P = .048). The P values for 5-FU (.678) and doxorubicin (.442) were not significant. These results suggest that tumors in folate-deficient hosts are relatively resistant to cyclophosphamide, and that the efficacy of this drug almost can be doubled by correcting folate deficiency.

Inhibition of MADB106 mammary tumor growth by chemotherapeutic drugs in rats of varying folate status. (□), Regular diet; (▨), low folate; (▧), high folate. After 7 weeks on the indicated diet conditions, tumor was injected subcutaneously and six rats per group were treated with cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg, 5-FU 50 mg/kg, doxorubicin 5 mg/kg, or vehicle alone. Two injections, 96 hours apart, were given when the tumors were palpable. Ninety-six hours after the second injection, tumor growth inhibitions were calculated. Using analysis of variance, the difference between the folate-deficient animals treated with cyclophosphamide and the folate-replete or supplemented rats was significant (P = .048). The Pvalues for 5-FU (.678) and doxorubicin (.442) were not significant.

Inhibition of MADB106 mammary tumor growth by chemotherapeutic drugs in rats of varying folate status. (□), Regular diet; (▨), low folate; (▧), high folate. After 7 weeks on the indicated diet conditions, tumor was injected subcutaneously and six rats per group were treated with cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg, 5-FU 50 mg/kg, doxorubicin 5 mg/kg, or vehicle alone. Two injections, 96 hours apart, were given when the tumors were palpable. Ninety-six hours after the second injection, tumor growth inhibitions were calculated. Using analysis of variance, the difference between the folate-deficient animals treated with cyclophosphamide and the folate-replete or supplemented rats was significant (P = .048). The Pvalues for 5-FU (.678) and doxorubicin (.442) were not significant.

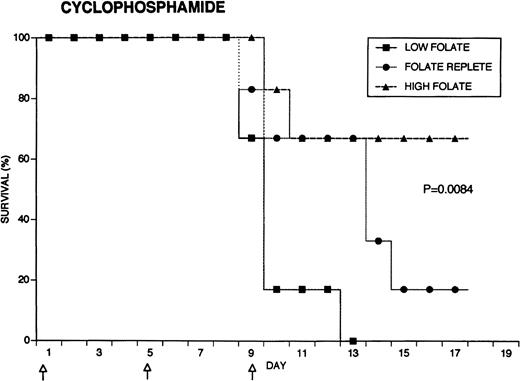

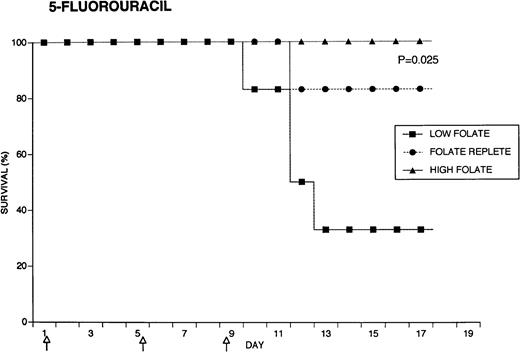

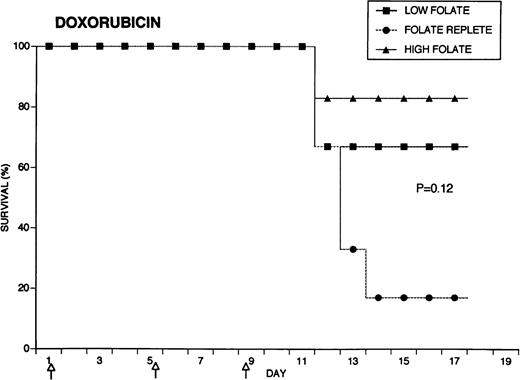

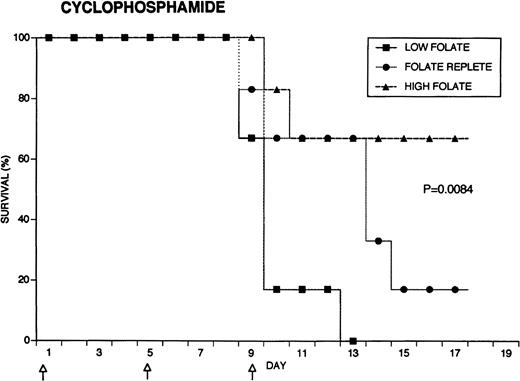

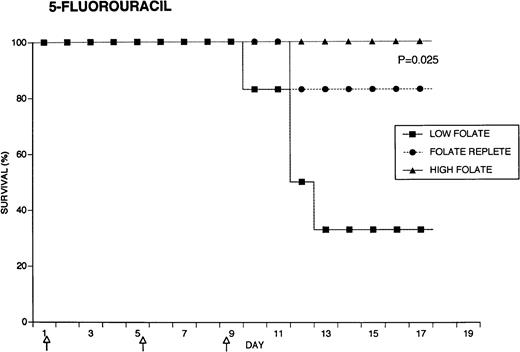

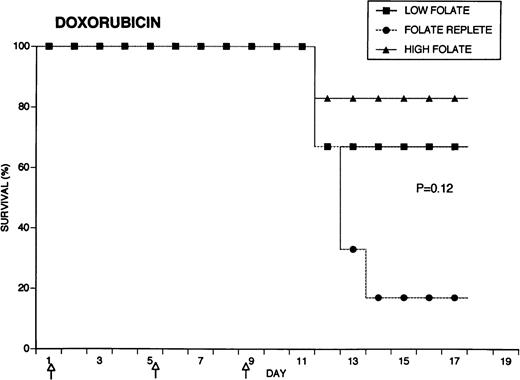

Because the efficacy studies described above indicated that folate status also might influence the toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs, further specific investigation of drug toxicity was performed. Weanling Fischer 344 rats were divided into three groups of six animals each and maintained for 7 weeks on the low folate diet, a folate replete diet, or the latter diet supplemented with folic acid injections. Cyclophosphamide 62.5 mg/kg, 5-FU 75 mg/kg, or doxorubicin 7.5 mg/kg were injected on days 1, 5, and 9 (50, 55, and 59 days after beginning the special diets). The animals were weighed daily and observed for signs of toxicity: loss of grooming behavior, lethargy, and loss of righting reflex. As shown in Fig 4, there were dramatic differences in survival in rats receiving cyclophosphamide or 5-FU related to folate status, with folate-supplemented animals doing better than folate replete animals, and both groups demonstrating better survival than folate-deficient rats. Thus, in the cyclophosphamide-treated group, all of the folate-deficient animals were dead by day 12, while the majority of the high folate animals survived until the end of the experiment, 1 week after the last injection of chemotherapy. Similarly, there were no deaths in the high folate animals treated with 5-FU, while two thirds of folate-deficient rats treated with this drug died by day 12. These differences were statistically significant (P = .0084 for cyclophosphamide, P = .025 for 5-FU) by the Log-Rank test. In contrast, doxorubicin-treated rats did not show a relationship between survival and folate status: the folate-supplemented rats did best, the folate-deficient group was intermediate, and the folate-replete group did the worst (P = .12). Analysis of variance indicated no significant differences among the weights of the dietary groups treated with cyclophosphamide, but high folate rats lost less weight than other dietary groups after treatment with 5-FU (P = .0143) and doxorubicin (P = .0067) (data not shown). Measurements of liver folate levels in rats supplemented with folic acid indicated that chemotherapy with these three drugs did not change tissue levels of the vitamin compared with untreated control animals (data not shown).

Effect of folate status on the toxicity of cancer chemotherapy. Three groups of 18 rats each were maintained on the indicated folate diets. After 7 weeks, six animals from each group were treated with either cyclophosphamide 62.5 mg/kg (top), 5-FU 75 mg/kg (middle), or doxorubicin 7.5 mg/kg (bottom). Drugs were injected three times at 96-hour intervals (arrows). Survivals were significantly different for cyclophosphamide (P = .0084) and 5-FU (P = .025), but not for doxorubicin (P = .12) by the Log-Rank test.

Effect of folate status on the toxicity of cancer chemotherapy. Three groups of 18 rats each were maintained on the indicated folate diets. After 7 weeks, six animals from each group were treated with either cyclophosphamide 62.5 mg/kg (top), 5-FU 75 mg/kg (middle), or doxorubicin 7.5 mg/kg (bottom). Drugs were injected three times at 96-hour intervals (arrows). Survivals were significantly different for cyclophosphamide (P = .0084) and 5-FU (P = .025), but not for doxorubicin (P = .12) by the Log-Rank test.

DISCUSSION

The results of these experiments indicate that nutritional folate status influences the efficacy and toxicity of cancer chemotherapy in rats. The extent of this influence varied by chemotherapeutic agent. Cyclophosphamide, a bifunctional alkylating agent, was only half as effective at inhibiting the growth of a rat mammary tumor and was much more toxic in folate-deficient rats. Although 5-FU and doxorubicin tended to be less effective at controlling tumor growth in folate-deficient rats, these effects were not statistically significant. The toxicity of 5-FU was significantly greater in folate-deficient rats than in folate replete or supplemented rats, while there was no clear effect of folate status on the toxicity of doxorubicin.

Considering the large number of patients who receive chemotherapy each year and the substantial number of these individuals who are likely to have a nutritional abnormality of folate metabolism, it is surprising that so little attention has been paid to the interactions of chemotherapeutic agents and folate. Parchure et al16 found that high doses of folate potentiated the cytotoxicity of methotrexate, 5-FU, cytosine arabinoside, or mitomycin C against P388 lymphocytic leukemia in mice and prolonged survival, possibly by changes in purine and pyrimidine supplies. In contrast, folate supplementation (5 mg/day) of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in remission increased their tolerance of 6-mercaptopurine and raised a concern that folate supplements might interfere with therapy.17 The ability of folate cofactors to enhance the cytotoxicity of 5-FU by forming a stable complex that inhibits thymidylate synthetase is well described,18 and folate levels are known to affect the efficacy and toxicity of 5-FU. For example, Chéradame et al19 have shown that the response of patients with head and neck cancer to 5-FU was correlated with tumoral reduced folate pools. The distribution of reduced folates was significantly higher for complete responders in comparison to patients with a partial or no response.19 Recent studies in a dietary folic acid-depleted mouse model indicated that C3H mouse mammary adenocarcinomas were somewhat less responsive to 5-FU alone compared with folate replete animals.20 Leucovorin administration 1 hour before 5-FU suppressed tumor growth 80% in folate-depleted mice. However, the administration of leucovorin at an improper time before 5-FU (12 hours) not only did not potentiate, but actually resulted in tumor growth stimulation.20 Similarly, studies of the effects of folinic acid in 5-FU induced killing of human tumor cell lines in vitro found that the cell of origin, the dose, and the duration of exposure to folinic acid all influenced cytotoxicity.21 The addition of very high doses of folic acid (125 mg/kg) increased the toxicity of 5-FU in mice.16In humans, stomatitis and diarrhea tend to be more frequent when folinic acid is added to 5-FU than with 5-FU alone and is the dose-limiting toxicity.22 However, hematologic toxicity tends to be less with the combination of folinic acid/5-FU than with 5-FU alone.22 These studies emphasize the complex interactions of folate status and chemotherapy.

A further example of this complexity is the interaction of folate status and antifols. In 1962, Potter and Briggs7 reported that folate-deficient mice were extremely sensitive to amethopterin. More recently, this sensitivity was confirmed with 5,10-dideazatetrahydrofolic acid (DDATHF, Lometrexol). This agent interferes with de novo purine synthesis by inhibition of the two folate-dependent enzymes along that pathway, glycinamide ribonucleotide and aminoimidazole carboxamide transformylase. Mice fed a low folate diet for a short period became more than 1,000-fold more sensitive to the lethality of DDATHF than animals fed a standard laboratory diet.23 Moderate folate supplementation (about 6 mg/kg/d orally) allowed complete suppression of C3H mammary adenocarcinoma without drug toxicity.23 However, at high levels of folic acid intake (about 2,000 mg/kg/d orally), the antitumor activity of the drug was completely blocked.23 The applicability of these preclinical studies in rodents to humans is indicated by the observation that dietary folate supplementation of phase I patients has been reported to reduce DDATHF drug toxicity, allow further dose escalation, and preserve antitumor activity.24 Thus, the effect of folate status on the efficacy and toxicity of chemotherapy appears to vary depending on the drug, the tumor cell type, and the folate level. In some circumstances, the correction of folate deficiency or additional supplementation may be beneficial, while in other circumstances, it may be detrimental.

Further complicating the issue is the fact that folate levels modulate tumor behavior independent of any effects on chemotherapy. The results presented here support older observations that dietary folate deficiency inhibits the growth of tumors.6,7 We found that nutritional folate deficiency of moderate or marked degree significantly slowed rat mammary tumor growth compared with animals on a folate replete diet. However, additional supplementation with large amounts of folic acid daily did not significantly increase the rate of tumor growth compared with rats ingesting the folate replete diet alone. This observation is consistent with in vitro studies indicating that supplementation with folic acid above levels required for cell replication does not shorten the cell doubling time (reviewed in Branda25). Therefore, it appears that correction of folic acid deficiency will release the inhibition of tumor growth rate, but folate supplementation does not accelerate the rate.

Measurement of folate levels showed that tumor levels were lower than hepatic levels, but that the two levels were correlated. The folate status of the MADB106 mammary tumor recovered from rats on the folate replete diet, 0.091 ± 0.074 μg/g wet weight, was comparable to folate levels previously published for Walker carcinosarcoma 256 in rats (0.37 ± 0.13 μg/g tissue) and for a variety of human cancers (0.05 to 0.5 μg/g of tumor).6,8 Rosen and Nichol6 concluded that the folic acid content of Walker carcinosarcoma 256 was less influenced than the liver by the dietary level of the vitamin because of the higher capacity of the liver to store folate. On the other hand, Gailani et al8 found that in patients on a folate-deficient diet, the rate of folate depletion in the tumor tissue roughly paralleled the rate of depletion in liver and blood. More recently, Raghunathan et al26 reported that accumulation of folate compounds was approximately simultaneous in plasma and mammary adenoncarcinoma in mice, but delayed in liver. They found more active metabolism of folinic acid in the liver than in the tumor.26 It appears, then, that generally there is a direct relationship between blood, hepatic, and tumor folate levels, but in some neoplastic tissues, the folate level may be low in the face of normal blood and adjacent tissue folate levels.27

Taken together, our studies and those of others indicate that folate status influences the efficacy and/or the toxicity of some, but not all chemotherapeutic drugs. It also seems likely that nutritional folate deficiency retards the growth of tumors. Therefore, correction of folate deficiency may be detrimental to the host if the tumor cannot be treated effectively. Alternatively, if effective therapy is available, our studies suggest that correction of folate deficiency can be beneficial. We found that cyclophosphamide was nearly twice as effective, with less toxicity, in folate replete compared with folate-deficient animals. Because slowly dividing cells are relatively resistant to chemotherapy, the improved efficacy of cyclophosphamide in folate-supplemented animals may be secondary to increased proliferation compared with folate-deficient tumor cells. We recognize that rodents may not be an ideal model for the study of folate-chemotherapy interactions.28 Therefore, extrapolation of these results to humans should await controlled clinical trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Takamaru Ashikaga for his assistance with the statistical analyses and Dr John Lunde for his review of the tumor histology.

Supported by Grants No. CA 41843 and P30CA22435 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD.

Address reprint requests to Richard Branda, MD, Genetics Laboratory, University of Vermont, 32 N Prospect St, Burlington, VT 05401.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.