Abstract

The hematopoietic system is derived from ventral mesoderm. A number of genes that are important in mesoderm development have been identified including members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, and the Wnt gene family. Because TGF-β plays a pleiotropic role in hematopoiesis, we wished to determine if other genes that are important in mesoderm development, specifically members of theWnt gene family, may play a role in hematopoiesis. Three members of the Wnt gene family (Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, and Wnt-10B) were identified and cloned from human fetal bone stromal cells. These genes are expressed to varying levels in hematopoietic cell lines derived from T cells, B cells, myeloid cells, and erythroid cells; however, only Wnt-5A was expressed in CD34+Lin− primitive progenitor cells. The in vitro biological activity of these Wnt genes on CD34+Lin− hematopoietic progenitors was determined in a feeder cell coculture system and assayed by quantitating progenitor cell numbers, CD34+ cell numbers, and numbers of differentiated cell types. The number of hematopoietic progenitor cells was markedly affected by exposure to stromal cell layers expressing Wnt genes with 10- to 20-fold higher numbers of mixed colony-forming units (CFU-MIX), 1.5- to 2.6-fold higher numbers of CFU-granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM), and greater than 10-fold higher numbers of burst-forming units-erythroid (BFU-E) in the Wnt-expressing cocultures compared with the controls. Colony formation by cells expanded on theWnt-expressing cocultures was similar for each of the three genes, indicating similar action on primitive progenitor cells; however, Wnt-10B showed differential activity on erythroid progenitors (BFU-E) compared with Wnt-5A and Wnt-2B. Cocultures containing Wnt-10B alone or in combination with all three Wnt genes had threefold to fourfold lower BFU-E colony numbers than the Wnt-5A– or Wnt-2B–expressing cocultures. The frequency of CD34+ cells was higher inWnt-expressing cocultures and cellular morphology indicated that coculture in the presence of Wnt genes resulted in higher numbers of less differentiated hematopoietic cells and fewer mature cells than controls. These data indicate that the gene products of theWnt family function as hematopoietic growth factors, and that they may exhibit higher specificity for earlier progenitor cells.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

DURING VERTEBRATE gastrulation, invagination of cells between the ectodermal and endodermal germ layers brings ectoderm into apposition with endoderm. Through a series of soluble peptide growth factors and cell-cell interactions, the endoderm induces the ectoderm to form the mesodermal germ layer. The mesoderm is divided into ventral and dorsal regions with specific interactions and inducing factors leading to the formation of mesodermal cell types including blood, mesenchyme, kidney, muscle, and notochord. Studies from Xenopus have shown a multitude of genes involved in mesoderm induction including members of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family, and Wnt gene family.1

One member of the TGF-β superfamily, bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP-4), is a ventralizing factor in Xenopus2-7that induces hematopoiesis in embryoid bodies formed from mouse ES cells in vitro8 and stimulates GATA-2 expression in vivo.9 Gene targeting experiments have shown that BMP-4 and its receptor are required for ventral mesoderm formation.10,11 In addition, TGF-β has been shown to act as a bifunctional regulator of hematopoietic cellular activity due to its ability to either stimulate (cells of mesenchymal origin) or inhibit (cells of epithelial or neuroectodermal origin) cell proliferation and growth.12-14 TGF-β is a potent inhibitor of myeloid (CFU-GM), erythroid (BFU-E), megakaryocytic (CFU-MK), and multilineage (CFU-MIX) progenitor cells,12,13,15-21 but can enhance the growth of CFU-GM stimulated by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), GM-CSF, and interleukin-3 (IL-3).17 19 Due to the pleiotropic effects of members of the TGF-β superfamily on hematopoiesis and the role of members of this family on mesoderm induction, we hypothesized that other gene families that were important in mesoderm induction may have family members that played a role in hematopoiesis.

Wnts are secreted signaling factors which influence cell fate and cell behavior in developing embryos. At least 19 members of the family have been identified in diverse species ranging from round worm and insects to humans.22Wnt proteins are secreted glycoproteins that have been found to be associated with the cell surface or extracellular matrix of secreting cells and likely act locally due to these biochemical properties.23,24Wnt deficiencies prevent normal brain development25,26 and normal segmentation of insect embryos.27 Ectopic expression of Wnt genes induces axis duplication in frog embryos28 and mammary tumors in mice.29,30 Receptors for the Wnt ligands appear to be encoded by the frizzled (fz) gene family.31-33 Several members of the Wnt gene family play a role in mesoderm induction. xWnt-8 and xWnt-11 are expressed during embryogenesis in the prospective ventral and lateral mesoderm.34-36xWnt-8 expression after the midblastula stage in Xenopus embryos allows naive ectodermal cells to differentiate as ventral mesoderm in the absence of added growth factors.35 In contrast, xWnt-11 andXenopus nodal-related 3 (XNR3) gene act highly cooperatively in inducing secondary embryonic axes formation and dorsalization of ventral mesoderm.37

A role for members of the Wnt gene family in murine hematopoiesis was reported recently.38 Austin et al38 found expression of Wnt-5A and Wnt-10Bin mouse embryonic yolk sac, fetal liver, and fetal liver AA4+ hematopoietic progenitors and biological activity ofWnt-5A on purified murine hematopoietic progenitors. In this study we show that members of the Wnt gene family play a role in human hematopoiesis. Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, andWnt-10B are expressed in fetal bone marrow (FBM) stromal cells, FBM, adult BM, and hematopoietic cell lines. In addition, theseWnt genes have biological activity on hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells that is similar to or exceeds the activity of stem cell factor (SCF) or IL-3 based on their effect on hematopoietic colony formation, CD34 cell numbers, and cellular morphology. Activity appears to be the greatest on mixed lineage progenitors (CFU-MIX). Furthermore, the activity of the three genes is similar for most progenitors analyzed; however, Wnt-10B appears to have a distinct activity on erythroid progenitors (BFU-E) compared to Wnt-5A and Wnt-2B. Finally, receptors for theWnt genes have been identified on CD34+ progenitors from fetal and adult BM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fetal tissue samples.

Fetal bones were obtained from week 18 to 22 fetuses by informed consent and approval of the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Alameda, CA). FBM cells were obtained by flushing the marrow cavities of quartered fetal bones with Iscove’s modified DMEM (IMDM; BioWhitaker, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT). Pooled cells from the bones of a single donor were centrifuged for 8 minutes at 900 rpm (200g), 22°C to pellet the cells. Red blood cells were removed by resuspending the cell pellet in 0.84% ammonium chloride lysis solution for 5 minutes at 4°C. Mononuclear cells were isolated by centrifugation and washed once in IMDM supplemented with 10% FBS. FBM stromal cells (FBMSC) were obtained from the flushed bones. Typically, eight bones were used from each donor. The quartered fetal bones were placed in a 150-cm tissue culture dish (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) containing 10 mL of Whitlock-Witte Medium (WWM)39 and were laterally sliced into 1- to 3-mm chips using a sterile forceps and scalpel. Bone chips were divided between six 150-cm tissue culture dishes containing 25 mL of WWM. FBMSC cultures were incubated for 3 days at 37°C/5% CO2 in a humidified chamber (Fisher Scientific, Itasca, IL) to allow attachment and growth of stromal cells. On day 4 the medium was changed and on every other subsequent day until the bone chips were washed away and the stromal cells reached 70% to 90% confluence.

Adult tissue samples.

Adult bone marrow (ABM) aspirates (15 to 25 mL) were obtained from the posterior iliac crest of normal donors by informed consent and approval of the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board. Mononuclear cells from the ABM were isolated by density centrifugation using Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ).

Hematopoietic progenitor purification.

CD34+ cells were isolated from FBM and ABM using a CD34 purification kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CD34+ purities using this kit range from 80% to 95% (data not shown). CD34+Lin− progenitors were isolated by flow cytometry. CD34+ cells from ABM were pelleted by centrifugation at 900 rpm (200g), 22°C for 8 minutes. Cells were resuspended in D-PBS containing 0.02% gamimmune (Miles Inc, Elkhart, IN) and incubated for 10 minutes on ice. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in staining buffer (SB = Hanks’ balanced salt solution [HBSS], 2% FBS, 10 mmol/L HEPES) at 1 × 107 cells/mL. Cells were resuspended in SB containing a 1/100 dilution of a phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibody (MoAb) to CD34 (anti-HPCA2 MoAb; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) and 1/100 dilutions of a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated lineage panel consisting of MoAbs to CD2, CD14, CD15, CD19, and glycophorin A (Becton Dickinson). Cells were incubated for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were then washed with 10 mL of staining buffer, pelleted by centrifugation, and resuspended in SB containing 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma, St Louis, MO) at a final concentration of 2 × 106cells/mL. Stained cells were sorted using a FACSTAR Plus cell sorter (Becton Dickinson) equipped with dual argon ion lasers, the primary emitting at 488 nm and a dye laser (Rhodamine 6G) emitting at 600 nm (Coherent Innova 90, Santa Clara, CA). Gates were set to isolate viable cells based on propidium iodide staining, to isolate CD34+cells based on anti-CD34 staining of a CD34− control, and to isolate lineage-negative cells (Lin−) based on lineage panel staining of a CD34− control. Primitive progenitor cells (CD34+Lin−) were isolated using these three gates and were greater than 95% pure based on reanalysis of purified cells using the original gates (data not shown).

RNA isolation.

Total RNA was isolated from hematopoietic cells using RNA-STAT 60 (Tel-Test “B,” Friendswood, TX) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, pelleted cells were resuspended in 1 mL of RNA-STAT 60 per 5 × 106 cells by repeated pipetting. The cell lysate was incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature and extracted with 0.2 vol (based on initial RNA-STAT 60 vol) of chloroform by vortexing for 45 seconds. The sample was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 13,000 rpm (12,000g), 4°C in a microcentrifuge. The aqueous upper phase was transferred to a new tube and 0.5 vol of isopropanol was added and mixed by vortexing. The sample was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm (12,000g), 4°C in a microcentrifuge. The RNA was washed with 75% ethanol, briefly dried, and resuspended in RNAse-free water. RNA was quantitated using a DU 650 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.

PCR amplification was performed on isolated RNA samples using a RNA PCR Core Kit (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions, except that AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer) was substituted for AmpliTaq. One microgram of RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using random hexamers to prime first-strand synthesis. The synthesized cDNA was divided into quarters and used for PCR amplification. As a control, duplicate cDNA synthesis reactions were performed for each experiment without the addition of reverse transcriptase. All PCR reactions were performed using a Perkin Elmer 9600 thermal cycler. PCR amplification using degenerate primers (forward, 5′-nnngtcgacgcttgyaartgycaygg-3′; reverse, 5′-nnngttaactacgtrrcarcaccartg-3′) for the Wnt gene family was performed for 1 cycle at 94°C/12 min, 45 cyles at 94°C/25 s; 62°C/45 s; 72°C/30 s, and 1 cycle at 72°C/10 min. PCR amplification using specific primers for Wnt-5A(forward, 5′-caaggtgggtgatgccctgaaggag-3′; reverse, 5′-cgtctgcacggtcttgaactggtcgta-3′), Wnt-10B(forward, 5′-ggagggcggccccagagttcc-3′; reverse, 5′-aagctgccacagccatccaacagg-3′), and Wnt-2B(forward, 5′-cacctgctggcgtgcactctcaga-3′; reverse, 5′-gggctttgcaagtatggacgtccacagta-3′) were performed for 1 cycle at 94°C/12 min; 45 cycles at 94°C/25 s, 64°C/45 s, 72°C/30 s; and 1 cycle at 72°C/10 min. PCR amplification using degenerate primers (forward, 5′-nnngaattctayccngarmgnccnat-3′; reverse, 5′-nnnaagcttngcngcnarraacca-3′) for the fz gene family was performed for 1 cycle at 94°C/12 min; 45 cyles at 94°C/25 s, 63°C/45 s, 72°C/30 s; and 1 cycle at 72°C/10 min. Control PCR amplifications were performed using primers for the glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase cDNA (GAPD; forward, 5′-ggctgagaacgggaagcttgtcat-3′; reverse, 5′-cagccttctccatggtggtgaaga-3′) for 1 cycle at 94°C/12 min; 45 cycles at 94°C/25 s, 64°C/45 s, 72°C/30 s; and 1 cycle at 72°C/10 min. PCR amplifications for cytokine genes were performed using previously described primers40 41 except for the erythropoietin gene (EPO; forward, 5′-gcccgctctgctccgacac-3′; reverse, 5′-ctgcccgacctccatcctcttc-3′) using touchdown PCR consisting of 1 cycle at 94°C/12 min; 5 cycles at 94°C/10 s, 69°C/2 min; 5 cycles at 94°C/10 s, 67°C/2 min; 30 cycles at 94°C/10 s, 65°C/2 min plus 3 seconds per cycle; and 1 cycle at 72°C/10 min.

Subcloning of PCR fragments.

PCR fragments were separated on a 1% SeaPlaque Agarose (FMC, Rockland, ME)/1× TAE gel and purified from the agarose using a Wizard PCR Prep Kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated PCR fragments were subcloned using the pGEM-T vector kit (Promega). Individual clones were screened by restriction enzyme digestion for the presence of the PCR fragment.

FBMSC cDNA library construction.

Total RNA was isolated from FBMSC cultures using RNA-STAT 60. mRNA was isolated from 500 μg of total RNA using an Oligotex mRNA purification kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA). A size-fractionated cDNA library containing approximately 1 × 106 independent clones was constructed from the purified mRNA using a Zap Express cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and a cDNA Size Fractionation Column (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Average insert size for the library was 2.0 kb based on analysis of 20 independent clones (data not shown). The primary library was divided into 20 sublibraries for screening purposes. DNA from each sublibrary was screened by PCR for the presence of each Wnt gene. Positive sublibraries were plated onto 6 plates at 30,000 plaques per plate. Duplicate filters (Hybond-N; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) were prepared from each plate and screened using 32P-labeled PCR fragments (Random Prime Kit; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Positive plaques on duplicate filters were isolated using a Pasteur pipette and incubated in SM for 2 hours at room temperature. Phage stocks were titered and each clone was plated for secondary screening at a density of 1,000 plaques per plate. Individual plaques were identified and isolated as described above using 32P-labeled probes. Plasmids containing the cDNAs of interest were obtained by excision of an M13 intermediate and infection of helper cells as directed by the manufacturer (Stratagene).

DNA sequencing.

Sequencing reactions on candidate clones were performed using vector primers (T3 and T7) and an ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing reaction kit (Perkin Elmer) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reaction products were analyzed using an ABI PRISM 377 automated DNA sequencer. Additional primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) were synthesized based on the analyzed sequence to complete the cDNA sequence. At least two independent sequencing reads were performed along both strands of the entire cDNA.

Subcloning Wnt cDNAs into MSCVNeoEB.

Plasmid DNA was digested with Ssp I (Wnt-5A),BsaWI/Sph I (Wnt-2B), or EcoO109I (Wnt-10B) to release the cDNA insert with minimal 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR). The DNA was treated with T4 DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) to remove any overhangs. The DNA fragments were separated using a 1% SeaPlaque Agarose/1× TAE gel and the cDNA band purified from the agarose using a Wizard PCR prep kit. The isolated cDNA bands were subcloned into the pSK vector (Stratagene) digested with HincII. Orientation of the cDNA in pSK was determined using restriction digestion. All clones with the flanking EcoRI site at the 5′ end of the cDNA and the flanking Xho I site at the 3′ end were designated in the plus (+) orientation. Clones with the opposite orientation were designated in the minus (−) orientation. Plus orientation clones of Wnt-5A and Wnt-10B were digested with EcoRI and Xho I and subcloned into the corresponding sites of pMSCVNeoEB. The plus orientation clone of Wnt-2B was digested with EcoRI and Sal I and subcloned into theEcoRI and Xho I sites of pMSCVNeoEB. Presence of the cDNA in pMSCVNeoEB was confirmed by restriction digest usingEcoRI and Xho I and agarose gel electrophoresis.

Retroviral transduction of CV-1 cells.

Retroviral supernatants were prepared by electroporation of purified plasmid DNA into an amphotropic packaging cell line (BING).42 Transient supernatants were collected at 48 and 72 hours posttransfection, filtered using a 0.45-μmol/L filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA), aliquoted into cryovials (Nunc), and snap frozen in dry ice/methanol (Fisher Scientific). Supernatants were stored at −80°C for short term (<2 weeks) and under liquid nitrogen for long term. CV-1 cells from African Green Monkeys were infected with the retroviral supernatants for 2 hours in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma) at 37°C/5% CO2 in a humidified chamber. Retroviral supernatants were removed and fresh Incubation Medium (IM = IMDM/10% FBS/1% L-glutamine) was added to the infection plates. At 48 hours postinfection G418 (Life Technologies) was added to the media to a final concentration of 600 μg/mL. Cells were cultured at 37°C/5% CO2 until confluence and split using Trypsin/EDTA (BioWhitaker). A population of transduced cells was isolated after several weeks of culture in the presence of G418. After stabilization of the transduced populations, the G418 concentration in the IM was reduced to 50 μg/mL.

C57MG transformation assay.

C57MG cells were transduced with the three Wnt-expressing MSCVneoEB retroviral vectors and the MSCVneoB retroviral vector alone as described above. Populations were isolated by selection in G418 and evaluated for transformation as described.43 Briefly, transduced cells were plated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin, and 10 mg/mL of bovine pancreatic insulin (Sigma). On day 7 after the cells reached confluence, the formation of ball-forming colonies on the plate that may or may not shed into the culture media was examined to determine loss of contact inhibition. The transduced cells were also plated in HB-CHO basal salt medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) containing 10 mg/mL of bovine pancreatic insulin. On day 5 after reaching confluence the presence of colonies that have lost contact inhibition was determined. Untransformed cells grow as an epithelial monolayer that exhibits contact inhibition upon reaching confluency. Transformed cells lose contact inhibition and form colonies that continue to divide when confluency is reached.

Feeder cell cocultures.

Transduced CV-1 cells were plated into 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) containing IM at 50,000 cells per well. The cultures were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C/5% CO2 in a humidified chamber. Plates were irradiated with 6,000 cGy using a cesium-source irradiator (J.L. Shepherd and Associates, San Fernando, CA) and incubated for an additional 24 hours at 37°C/5% CO2. Medium was removed and 2 mL of IM containing CD34+Lin− ABM cells was added and the plates returned to the incubator. One milliliter of medium was removed on the third and fifth days of culture and replaced with 1 mL of fresh IM. Cultures containing growth factors IL-3 (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) or SCF (Amgen) at 100 ng/mL were also supplemented at day 3 and day 5 with IM containing the corresponding growth factor. On day 7 cells were removed for cytospin preparation, methylcellulose colony formation, and CD34 analysis.

Methylcellulose colony formation.

Cocultured cells were washed with IMDM and assayed for hematopoietic progenitor cells in a standard methylcellulose assay as described previously.44 45 CFU-GM, BFU-E, and CFU-MIX-derived colony formation in the methylcellulose culture system was stimulated by the addition of EPO, IL-3, GM-CSF, and SCF (Amgen) at 100 ng/mL.

CD34 analysis.

Cocultured cells were washed with SB and resuspended in SB containing 0.02% gamimmune. Cells were incubated on ice for 10 minutes. Cells were washed with SB, resuspended in 100 μL of SB containing a 1/100 dilution of phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD34 and a 1/50 dilution of FITC-conjugated anti-human PAN HLA, and incubated for 30 minutes on ice. Cells were washed with SB and resuspended in 1 mL SB containing 1 μg/mL propidium iodide. Stained cells were analyzed using a FACSTAR Plus cell sorter. The percentage of CD34+ cells was determined using gates set to analyze viable cells based on propidium iodide staining, to distinguish human cells from the CV-1 feeder cells based on expression of PAN HLA markers, and to identify CD34+ cells based on anti-CD34 staining of a CD34− control.

RESULTS

Identification of Wnt gene family members in hematopoietic tissues.

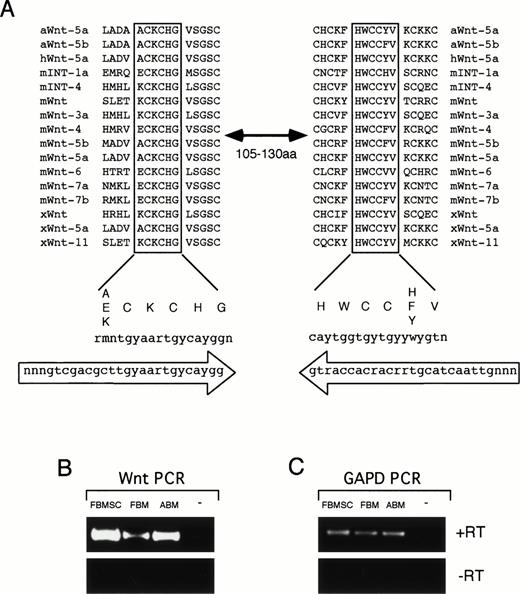

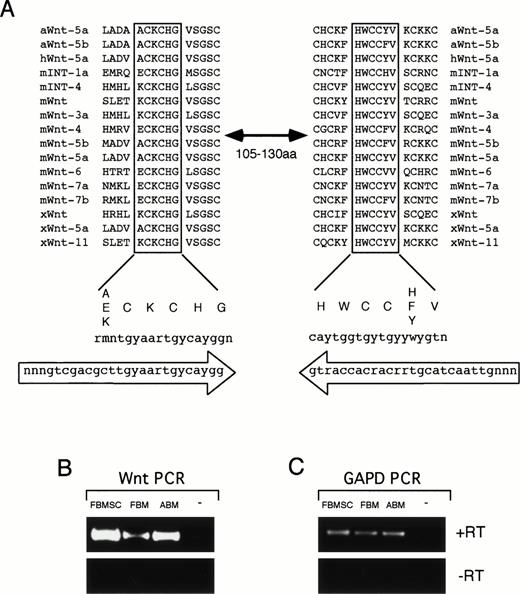

The expression of members of the Wnt gene family was determined by using PCR amplification with degenerate primers homologous to two conserved regions within the Wnt proteins (Fig 1A). These two regions are separated by 105 to 130 amino acids in different family members and PCR amplification with degenerate primers to these sequences results in DNA bands ranging in size from 369 to 444 bp. Because Wnt proteins can act in a paracrine or autocrine fashion, we analyzed the expression of Wnt genes in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and BM stromal cells.46 47 In addition, because many members of the Wnt genes are expressed early in development and are reduced in adult tissues, we analyzed Wnt gene expression in adult and fetal tissues. PCR amplification was performed on cDNA from FBM, ABM, and FBMSC. A band of the correct size range was detected from all three tissues, but not in a no-template control (Fig 1B). This band was specific for cDNA (+RT) because no bands were detectable in the absence of reverse transcriptase (−RT) during the cDNA synthesis step (Fig 1B). Control PCR amplification with primers to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPD) confirmed that the isolated RNA could be PCR amplified and the quantity of RNA used was similar for all three tissues (Fig 1C). The intensity of the PCR bands from the FBMSC was consistently stronger in several experiments than the band detected in FBM and slightly stronger than in ABM when corrected for GAPD expression (Fig 1B and data not shown). This expression analysis is consistent with the expression of Wnt genes within the human BM microenvironment, indicating a possible role for Wnt genes in human hematopoiesis.

Wnt degenerate PCR. (A) Alignment of two highly conserved regions of Wnt proteins from Axolotl (aWnt), mouse (mWnt), human (hWnt), and Xenopus (xWnt). These regions are separated by 105 to 130 amino acids in various family members. Consensus sequence for the aligned protein regions is shown below with codon sequence. Oligonucleotides used for the degenerate PCR are shown in large arrows indicating orientation of the primers. (B) RT-PCR results of Wnt degenerate primers on RNA from FBMSC, FBM, ABM, and a no-template control (−). Reverse transcription was performed with (+RT) or without (−RT) RT in the cDNA synthesis step. Equivalent amounts of RNA were used from each tissue for reverse transcription. One quarter of the cDNA was used for PCR amplification with the degenerate primers. (C) RT-PCR results using primers to GAPD. One quarter of the cDNA synthesized from FBMSC, FBM, and ABM was PCR amplified using the GAPD primers. No product was observed in (B) and (C) for the no-template control or when reverse transcriptase was omitted from the reactions.

Wnt degenerate PCR. (A) Alignment of two highly conserved regions of Wnt proteins from Axolotl (aWnt), mouse (mWnt), human (hWnt), and Xenopus (xWnt). These regions are separated by 105 to 130 amino acids in various family members. Consensus sequence for the aligned protein regions is shown below with codon sequence. Oligonucleotides used for the degenerate PCR are shown in large arrows indicating orientation of the primers. (B) RT-PCR results of Wnt degenerate primers on RNA from FBMSC, FBM, ABM, and a no-template control (−). Reverse transcription was performed with (+RT) or without (−RT) RT in the cDNA synthesis step. Equivalent amounts of RNA were used from each tissue for reverse transcription. One quarter of the cDNA was used for PCR amplification with the degenerate primers. (C) RT-PCR results using primers to GAPD. One quarter of the cDNA synthesized from FBMSC, FBM, and ABM was PCR amplified using the GAPD primers. No product was observed in (B) and (C) for the no-template control or when reverse transcriptase was omitted from the reactions.

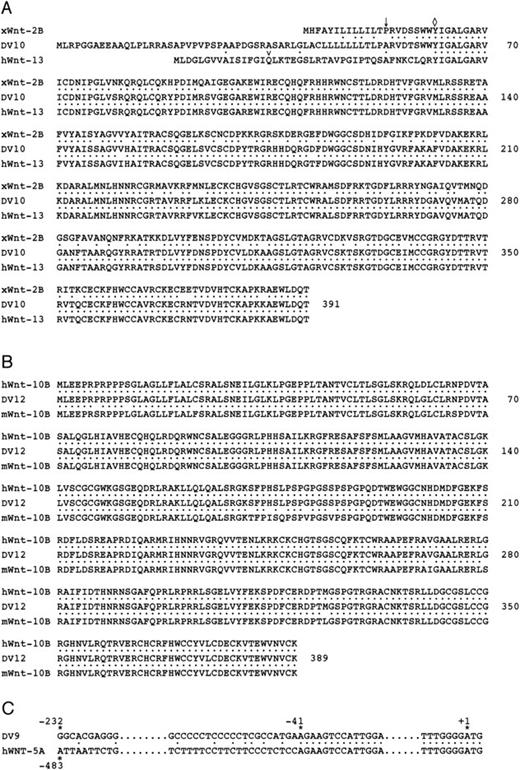

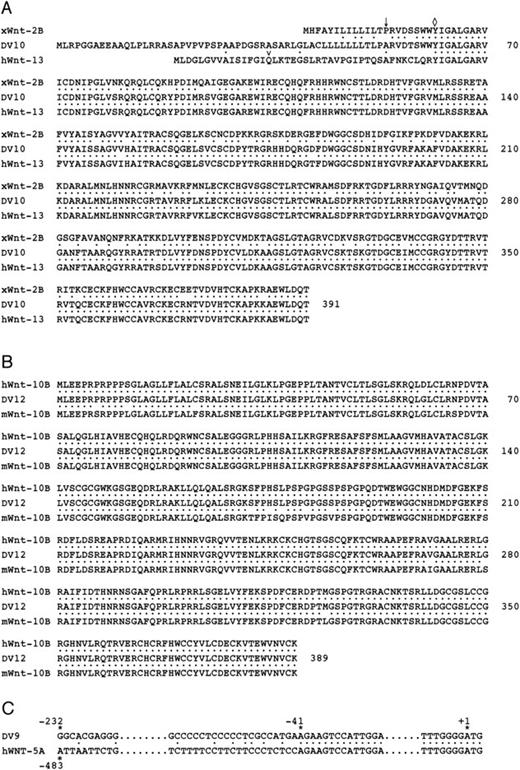

To determine which members of the Wnt gene family are expressed in hematopoietic cells, the identified PCR bands were isolated by gel purification and subcloned into the pGEM-T vector for sequence analysis. Twenty independent clones from each tissue were sequenced. A total of three members of the Wnt gene family were present in each of the three tissues based on sequence analysis of individual clones and designated DV9, DV10, and DV12. Because the FBMSC cDNA consistently gave the strongest band on PCR amplification, we used the gene fragments to screen an FBMSC cDNA library for full-length clones. Clones for each of the three genes were identified and purified to homogeneity by secondary screening. A total of two independent cDNA clones were sequenced for DV9 and DV10, and one independent clone for DV12. The Wnt open reading frame for each clone was identified and compared with the Genbank database of nonredundant clones. DV10 closely matches two sequences in the database, XenopusWnt-2B and human Wnt-13 (Fig 2A). The protein sequences of DV10 andWnt-13 are identical throughout most of the coding region (98.8% identity), but are divergent at the amino-terminus. The overall identity of DV10 to the XenopusWnt-2B gene is lower (81.6%), but the identity is consistent throughout the entire sequence. The DV10 sequence amino-terminal to the point of similarity between DV10 and Wnt-13 (Fig 2A, 5′ of ◊) matches thexWnt-2B sequence, but diverges at amino acids that are part of the putative signal peptides (Fig 2A, ↓). These data are consistent with DV10 being a human ortholog of the XenopusWnt-2Bgene. Furthermore, DV10 and Wnt-13 may be transcripts from the same gene that arise from alternate splicing or alternate promoter usage. Because of the sequence similarity between DV10 andxWnt-2B, we have designated the DV10 clone as humanWnt-2B.

Alignment of hematopoietic Wnt genes. (A) Alignment of clone DV10 with XenopusWnt-2B(xWnt-2B; Genbank accession no. U66288) and humanWnt-13 (hWNT-13; Genbank accession no. Z71621). Amino acid identities are indicated by dots (•). The putative site of signal peptide cleavage based on hydrophobicity analysis is shown inxWnt-2B and DV10 by an arrow (). The homology between DV10 and hWnt-13 begins at the amino acid indicated by a diamond (◊). Amino acid numbering is shown on the right. Numbering begins with the initiation codon of DV10. (B) Alignment of clone DV12 with human Wnt-10B (hWnt-10B; Genbank accession no. U81787) and mouse Wnt-10B (mWnt-10B; Genbank accession no.U20658). (C) Alignment of the 5′ UTR of clone DV9 and humanWnt-5A (hWnt-5A; Genbank accession no. L20861). Numbering begins at the first nucleotide of the initiation codon. Homology between the two sequences begins at −41 and continues throughout the coding region. The 5′ UTRs for DV9 andhWnt-5A are 283 and 488 nucleotides, respectively.

Alignment of hematopoietic Wnt genes. (A) Alignment of clone DV10 with XenopusWnt-2B(xWnt-2B; Genbank accession no. U66288) and humanWnt-13 (hWNT-13; Genbank accession no. Z71621). Amino acid identities are indicated by dots (•). The putative site of signal peptide cleavage based on hydrophobicity analysis is shown inxWnt-2B and DV10 by an arrow (). The homology between DV10 and hWnt-13 begins at the amino acid indicated by a diamond (◊). Amino acid numbering is shown on the right. Numbering begins with the initiation codon of DV10. (B) Alignment of clone DV12 with human Wnt-10B (hWnt-10B; Genbank accession no. U81787) and mouse Wnt-10B (mWnt-10B; Genbank accession no.U20658). (C) Alignment of the 5′ UTR of clone DV9 and humanWnt-5A (hWnt-5A; Genbank accession no. L20861). Numbering begins at the first nucleotide of the initiation codon. Homology between the two sequences begins at −41 and continues throughout the coding region. The 5′ UTRs for DV9 andhWnt-5A are 283 and 488 nucleotides, respectively.

Sequence comparison of DV12 to the Genbank database indicated that DV12 is identical to human Wnt-10B and highly homologous to mouseWnt-10B (Fig 2B). DV9 is identical to human Wnt-5A; however, the similarity begins 41 nucleotides 5′ of the initiation codon and the majority of the 5′ UTRs are divergent between DV9 and Wnt-5A (Fig 2C). The divergence may represent alternate promoter usage or alternate splicing of the Wnt-5Agene in fetal bone stromal cells. The expression of Wnt-5A andWnt-10B has also been found in mouse embryonic yolk sac, fetal liver, and fetal liver AA4+ hematopoietic progenitors, further supporting a role for members of the Wnt gene family in hematopoiesis; however, expression of Wnt-2B was not detected in this study.38

Expression analysis of Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, and Wnt-10B.

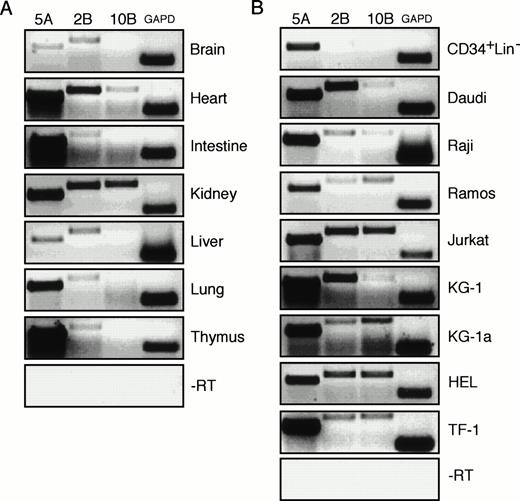

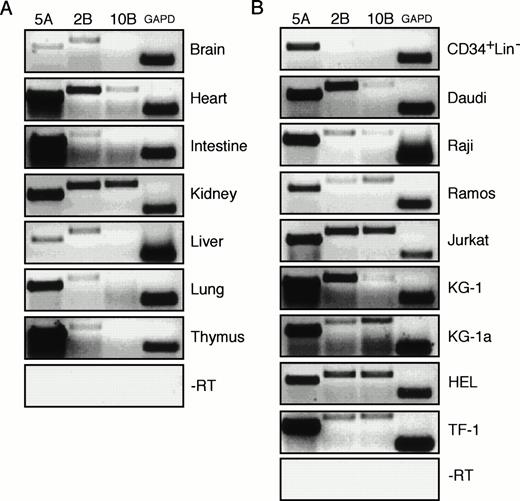

Initial analysis of RNA expression using Northern blot analysis resulted in negative signals for all three genes for every tissue examined (data not shown). Hybridization of the same blots with a β-actin probe showed that the RNA was not degraded and of sufficient quantity on the blots to be detected using the control (data not shown). Therefore, the levels of Wnt-5A, Wnt-10B, andWnt-2B expression are below the sensitivity of Northern blot hybridization. This finding is common for many of the Wnt genes analyzed and may represent low levels of RNA expression in the tissues, restricted expression in a subset of cells within each tissue, or a combination of both. To determine the expression pattern of the isolated hematopoietic Wnt genes PCR amplification was performed on RNA isolated from week 18 to 22 human fetal tissue (Fig 3A) and hematopoietic cells and cell lines (Fig 3B) using Wnt-specific primers. Wnt-5A was expressed at various levels in all fetal tissues examined. Strong PCR bands for Wnt-5A were detected in heart, intestine, kidney, and thymus compared with the GAPD control and weak bands in liver and brain. Wnt-2B is expressed in most tissues, but the PCR bands are faint compared with Wnt-5A. The strongest PCR bands forWnt-2B are in heart and kidney, with faint bands in brain, liver, lung, and thymus. A very weak band is present in intestine upon longer exposure. Wnt-10B shows the most restricted expression pattern with a strong PCR band in kidney alone. A faint PCR band forWnt-10B is detectable in heart, but not in any additional fetal tissue examined.

Expression analysis of Wnt genes. RT-PCR analysis of fetal tissue (A) and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and cell lines (B). Wnt-specific primers (described in Materials and Methods) were used for PCR amplification of cDNA from brain, heart, intestine, kidney, liver, lung, thymus, ABM CD34+Lin− hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, B-cell lines (Daudi, Ramos, Raji), a T-cell line (Jurkat), myeloid cell lines (KG-1, KG-1A), and erythroid cell lines (HEL, TF-1). Each tissue was performed in duplicate with or without the addition of RT in the cDNA synthesis step. The PCR results for each tissue in the absence of RT was identical and is shown for only one tissue (−RT) for each set of samples. The cDNA synthesized from each tissue was divided into four equivalent portions and amplified with primers toWnt-5A (5A), Wnt-2B (2B), Wnt-10B (10B), and GAPD. In addition, for each PCR primer pair a no template control was also performed. No product was detected in any no template control (data not shown) or in any control with RT omitted (−RT, and data not shown).

Expression analysis of Wnt genes. RT-PCR analysis of fetal tissue (A) and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and cell lines (B). Wnt-specific primers (described in Materials and Methods) were used for PCR amplification of cDNA from brain, heart, intestine, kidney, liver, lung, thymus, ABM CD34+Lin− hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, B-cell lines (Daudi, Ramos, Raji), a T-cell line (Jurkat), myeloid cell lines (KG-1, KG-1A), and erythroid cell lines (HEL, TF-1). Each tissue was performed in duplicate with or without the addition of RT in the cDNA synthesis step. The PCR results for each tissue in the absence of RT was identical and is shown for only one tissue (−RT) for each set of samples. The cDNA synthesized from each tissue was divided into four equivalent portions and amplified with primers toWnt-5A (5A), Wnt-2B (2B), Wnt-10B (10B), and GAPD. In addition, for each PCR primer pair a no template control was also performed. No product was detected in any no template control (data not shown) or in any control with RT omitted (−RT, and data not shown).

Expression analysis of Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, andWnt-10B in various hematopoietic cell lines and CD34+Lin− stem/progenitor cells is shown in Fig 3B. Again, Wnt-5A is expressed in all tissues tested with the strongest PCR bands and is the only Wnt gene detected in primitive progenitors from ABM (CD34+Lin−). Expression of Wnt-5Awas documented in B-cell lines (Daudi, Raji, and Ramos), a T-cell line (Jurkat), myeloid cell lines (KG-1 and KG-1a), and erythroid cell lines (HEL and TF1). Expression of Wnt-2B is detectable in all cell lines with strong PCR bands in the Daudi, Jurkat, and KG-1 cell lines.Wnt-10B expression was detected in most cell lines, but the bands were weak compared with the Wnt-5A bands. The strongest bands for Wnt-10B were detected in the Jurkat and HEL cell lines. Wnt-10B has been reported to be expressed in T-cell lines and in T cells, and is consistent with these findings.48 PCR bands for Wnt-2B andWnt-10B were weaker than the bands for Wnt-5A for all cell lines tested. No expression of Wnt-2B and Wnt-10Bwas detected in primitive progenitor cells (CD34+Lin−) isolated from ABM. Because all three Wnt genes were detected by the degenerate primers in ABM (Fig 1B) it appears that the expression results in CD34+Lin− cells suggest thatWnt-2B and Wnt-10B may be restricted to committed progenitors or more mature cells.

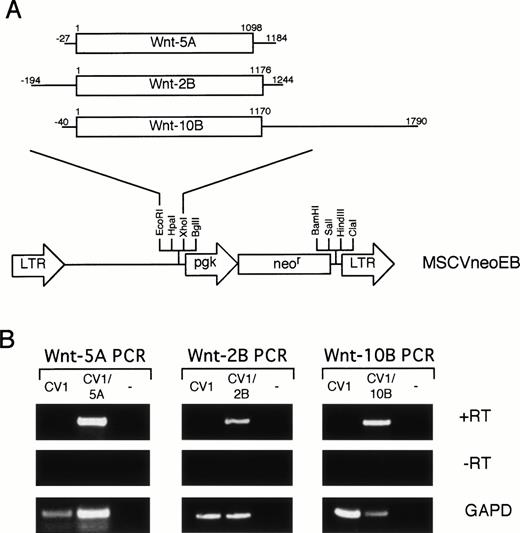

Establishment of Wnt-expressing feeder cells.

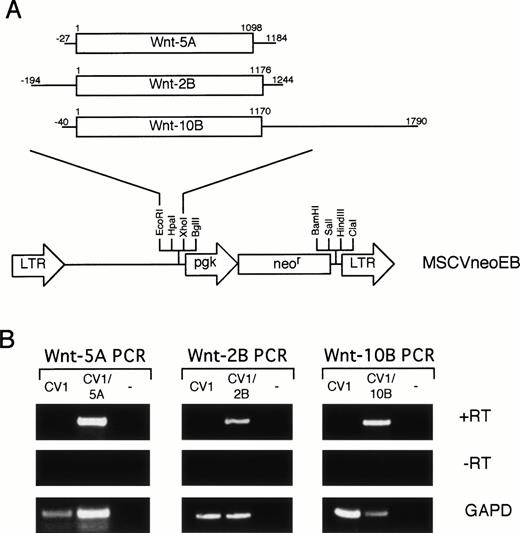

To determine the biological activity of the isolated Wnt genes on hematopoietic progenitors, an in vitro coculture system was established. The Wnt genes were subcloned into the MSCVneoEB retroviral vector (Fig 4A) so that theWnt gene was expressed from the LTR promoter and a neomycin-resistance gene was expressed from the internal mouse PGK promoter. Retroviral integration can be selected by resistance to G418. A series of fibroblastic cell lines were evaluated with the Wntdegenerate PCR primers (Fig 1) to identify a feeder cell host for retroviral transduction (data not shown). CV-1 cells were selected for their growth characteristics and lack of expression of Wntgenes. Amphotropic retroviral supernatants were used to transduce the CV-1 cells. A G418-resistant population was isolated and the expression of the transduced Wnt gene was confirmed by PCR (Fig 4B). Specific PCR primers were used to amplify cDNA (+RT) from CV-1 cells, from CV-1 transduced cells, and a no template control for each retroviral construct. Each transduced population (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, and CV1/10B) contained a band of the correct size while none of the −RT controls contained bands (Fig 4B). In addition, the CV1 control was negative for each specific primer set. These data are consistent with expression of each cDNA in the corresponding transduced cell population.

Retroviral transduction of CV-1 cells. (A) Retroviral constructs. Each Wnt cDNA was digested with restriction enzymes to eliminate 5′ and 3′ UTR and subcloned into the MSCVneoEB vector at the EcoRI and Xho I sites downstream of the LTR promoter. A line represents the 5′ and 3′ UTRs and an open box represents the coding sequence. Numbering for each cDNA begins at the first nucleotide of the initiation codon. (B) RT-PCR analysis of transduced CV-1 cells. Specific primers for each of the Wntgenes were used to analyze expression of the transduced genes in cDNA (+RT) from CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector (CV1), from each transduced population (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, CV1/10B), and from a no-template control (−). A control lacking RT in the cDNA synthesis step (−RT) confirms that the PCR bands in the +RT samples are specific for RNA. PCR with GAPD primers was also performed (GAPD) to confirm the ability of the isolated RNA to be PCR amplified and to standardize for loading.

Retroviral transduction of CV-1 cells. (A) Retroviral constructs. Each Wnt cDNA was digested with restriction enzymes to eliminate 5′ and 3′ UTR and subcloned into the MSCVneoEB vector at the EcoRI and Xho I sites downstream of the LTR promoter. A line represents the 5′ and 3′ UTRs and an open box represents the coding sequence. Numbering for each cDNA begins at the first nucleotide of the initiation codon. (B) RT-PCR analysis of transduced CV-1 cells. Specific primers for each of the Wntgenes were used to analyze expression of the transduced genes in cDNA (+RT) from CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector (CV1), from each transduced population (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, CV1/10B), and from a no-template control (−). A control lacking RT in the cDNA synthesis step (−RT) confirms that the PCR bands in the +RT samples are specific for RNA. PCR with GAPD primers was also performed (GAPD) to confirm the ability of the isolated RNA to be PCR amplified and to standardize for loading.

Protein levels of each Wnt gene could not be obtained due to a lack of antibodies specific to these protein products; however, the retroviral constructs were tested in a C57MG transformation assay to evaluate the transforming ability of each Wntgene.43 C57MG cells are derived from normal rat mammary epithelium and respond to some Wnt proteins in a paracrine or autocrine manner by acquiring a transformed phenotype. C57MG cells were transduced with transient ecotropic retroviral supernatants generated by transfection of BOSC cells with the retroviral constructs.42 A transduced population was generated by selection in G418 for 3 weeks. The G418-resistant cells were plated in medium containing FBS to assay for changes to the cells growth characteristics and in HB-CHO basal salt medium to assay for loss of contact inhibition. Results of the C57MG transformation assay are summarized in Table 1. The greatest transformation was seen with the cells transduced with theWnt-10B retroviral vector. Wnt-10B cultures formed and shed ball-forming colonies of cells into the media and produced large numbers of colonies that lacked contact inhibition in serum-free medium. Wnt-2B transduced cells also induced transformation but with fewer colonies in serum-free medium and the formation of ball-forming colonies that did not shed into the medium. Transformation by Wnt-5A was only visible by the presence of a few ball-forming colonies, but no loss of contact inhibition was observed in serum-free medium. These findings are consistent with distinct effects on cell growth by different members of the Wnt gene family. Furthermore, our findings of the weak transformation ofWnt-5A are consistent with the analysis of mouse Wnt-5Ain this assay.43 Also, Wong et al43 reported that the Wnt-2 gene fell into an intermediate transformation group that was greater than Wnt-5A, but less than a highly transforming group that contained Wnt-1, Wnt-3A, andWnt-7A. The Wnt-2B gene that we have identified is closely related to the Wnt-2 gene by sequence homology and our transformation results are consistent with Wnt-2B being functionally related to Wnt-2. In conclusion, the results with the C57MG transformation assay are consistent with previous analysis ofWnt genes and indicate that these retroviral constructs are able to produce active protein.

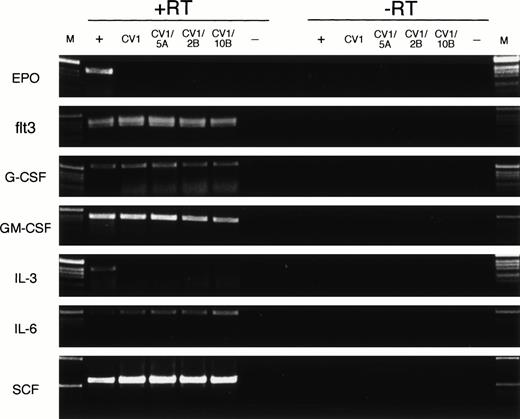

Finally, we evaluated the expression of various cytokine genes to verify that transduction with Wnt genes did not alter the expression pattern of the feeder cells. Specific PCR primers for EPO, flt3 ligand, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, and SCF were used to amplify cDNA (+RT) and mRNA (−RT) from a posititive control for cytokine expression (+), from CV-1 cells (CV1), from CV-1 transduced cells (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, and CV1/10B), and a no-template (−) control (Fig 5). Expression of flt3 ligand, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-6, and SCF was detected in each cDNA population (+RT) tested and not in the no-template control or the no–reverse transcriptase controls (−RT). No expression of EPO or IL-3 was detected in the CV-1–derived cells, but was detected in the positive control samples (Fig 5, +). No detectable differences in cytokine expression are seen between the untransduced CV-1 cells (Fig 5, CV1) and each of the transduced cell populations (Fig 5, CV1/5A, CV1/2B, CV1/10B) for each of the tested cytokine genes. These data indicate that retroviral transduction of CV-1 feeder cells with Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, or Wnt-10B does not alter the expression pattern of EPO, flt3 ligand, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, or SCF as detected by RT-PCR.

Expression of cytokine genes by feeder cells. RT-PCR analysis was performed on cDNA (+RT) or mRNA (−RT) from positive control cells (+), untransduced CV-1 cells (CV1), CV-1 cells transduced with Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, or Wnt-10B(CV1/5A, CV1/2B, or CV1/10B, respectively), and a no-template control (−). The positive control cells were human fetal brain (EPO), human FBM (flt3, IL-6, SCF), human fetal kidney (G-CSF), or KG-1 cells (GM-CSF, IL-3). DNA size ladder (M) consists of a 1-kb ladder (Life Technologies). Expected size products for the PCR amplification reactions are 410 bp (EPO), 390 bp (flt3), 547 bp (G-CSF), 396 bp (GM-CSF), 401 bp (IL-3), 495 bp (IL-6), and 590 bp (SCF).

Expression of cytokine genes by feeder cells. RT-PCR analysis was performed on cDNA (+RT) or mRNA (−RT) from positive control cells (+), untransduced CV-1 cells (CV1), CV-1 cells transduced with Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, or Wnt-10B(CV1/5A, CV1/2B, or CV1/10B, respectively), and a no-template control (−). The positive control cells were human fetal brain (EPO), human FBM (flt3, IL-6, SCF), human fetal kidney (G-CSF), or KG-1 cells (GM-CSF, IL-3). DNA size ladder (M) consists of a 1-kb ladder (Life Technologies). Expected size products for the PCR amplification reactions are 410 bp (EPO), 390 bp (flt3), 547 bp (G-CSF), 396 bp (GM-CSF), 401 bp (IL-3), 495 bp (IL-6), and 590 bp (SCF).

Biological activity of Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, and Wnt-10B on hematopoietic progenitor cells.

The biological activity of the Wnt genes on hematopoietic progenitors was assayed using the retrovirally transduced CV-1 cells. Cocultures were established containing the CV-1 feeder cells alone (CV1), each of the retrovirally transduced populations (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, and CV1/10B), and a feeder cell coculture that contained all three of the retrovirally transduced populations (CV1/5A/2B/10B). In addition, cocultures were established that contained the CV-1 feeder cells alone with exogenously added recombinant human IL-3 (CV1 + rhIL-3) or recombinant human SCF (CV1 + rhSCF). CD34+Lin− cells were purified by flow cytometry (>95% purity, data not shown) and plated onto the feeder cells (day 0). The biological activity of the Wnt genes was assessed at day 7 by assaying the numbers of hematopoietic progenitor cells, determining the frequency of CD34+ cells, and evaluating the morphology of the expanded cell populations.

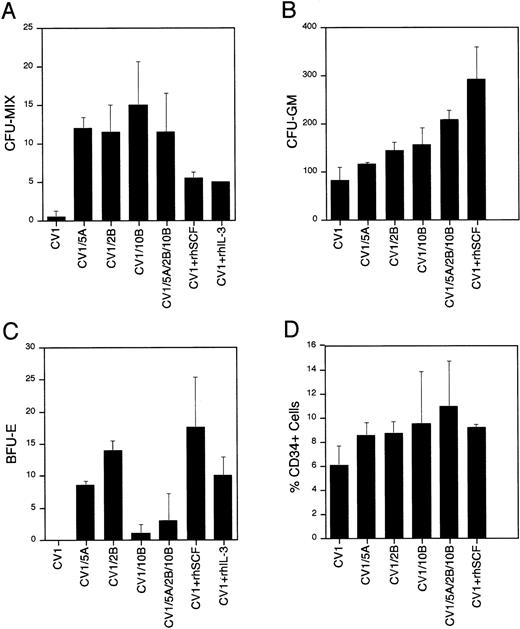

These studies indicate that the Wnt genes have a profound effect on hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells. EachWnt-expressing coculture contained a 23- to 30-fold increase in CFU-MIX compared with the control (Fig 6A). In addition, the CFU-MIX levels were twofold to threefold higher in theWnt-expressing cocultures than in the cocultures containing SCF or IL-3. No additional effect was seen when combining all threeWnt genes than in each of the Wnt genes alone. In addition, conditioned media from the transduced CV-1 feeder cells lacked any activity on hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells (data not shown), indicating that the activity observed in the coculture experiments is restricted to the cell surface/extracellular matrix. Furthermore, we have not detected epitope-tagged Wntproteins in the culture supernatants of transduced feeder cells (data not shown), which is consistent with the theory that the Wntproteins are acting directly on hematopoietic progenitors and the biological activity observed is greater than the effect of soluble forms of IL-3 or SCF.

Biological activity of Wnt genes on hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Results of methylcellulose colony formation (A through C) and CD34 phenotypic analysis (D) are shown. Colony numbers (A through C) are mean values with standard deviation bars from duplicate plates. A total of three tissues were examined. Percentage CD34+ cells is the mean of two experiments with standard deviation bars. The cocultures represented are CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector (CV1), CV-1 cells transduced with each of theWnt genes (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, and CV1/10B), an equal mixture of CV-1 cells transduced with each of the Wnt genes (CV1/5A/2B/10B), CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector and 100 ng/mL of recombinant human SCF added to the culture medium (CV1 + rhSCF), and CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector and 100 ng/mL of recombinant human IL-3 added to the culture medium (CV1 + rhIL-3).

Biological activity of Wnt genes on hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Results of methylcellulose colony formation (A through C) and CD34 phenotypic analysis (D) are shown. Colony numbers (A through C) are mean values with standard deviation bars from duplicate plates. A total of three tissues were examined. Percentage CD34+ cells is the mean of two experiments with standard deviation bars. The cocultures represented are CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector (CV1), CV-1 cells transduced with each of theWnt genes (CV1/5A, CV1/2B, and CV1/10B), an equal mixture of CV-1 cells transduced with each of the Wnt genes (CV1/5A/2B/10B), CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector and 100 ng/mL of recombinant human SCF added to the culture medium (CV1 + rhSCF), and CV-1 cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector and 100 ng/mL of recombinant human IL-3 added to the culture medium (CV1 + rhIL-3).

The number of assayable CFU-GM is also increased in theWnt-expressing cocultures compared with the control cultures (Fig 6B). Wnt-expressing cocultures contained 1.5- to 2.6-fold higher numbers of CFU-GM compared with the control. The greatest number of colonies in the Wnt-expressing cocultures was seen in the coculture expressing all three of the Wnt genes. This finding was the only example in this study where the presence of all threeWnt genes resulted in a greater effect than in cocultures containing each of the Wnt genes individually. CFU-GM colony numbers in the Wnt-expressing cocultures were greater than in the cocultures containing IL-3, but less than in the SCF containing cocultures. These findings are consistent with expansion/retention of a CFU-GM progenitor in the Wnt-expressing coculture that is greater than the control or IL-3 coculture, but less than the SCF coculture.

The Wnt-expressing cocultures also showed a profound effect on in vitro erythropoiesis (Fig 6C). The cocultures expressingWnt-5A or Wnt-2B contain numbers of BFU-E that are similar to the cocultures containing SCF or IL-3 alone. By contrast, the numbers of BFU-E assayed from the Wnt-10B–expressing cocultures were lower when compared with the cocultures expressingWnt-5A or Wnt-2B. The failure of theWnt-10B-expressing culture to expand/retain a BFU-E progenitor population appears to be dominant because the coculture containing all three Wnt genes has a low number of BFU-E colonies that is closer to the BFU-E colony number of the cocultures expressingWnt-10B alone. If the activity measured was simply an expansion/retention of a BFU-E progenitor, then the coculture expressing all three Wnt genes would be similar to the cocultures expressing Wnt-5A or Wnt-2B. Therefore, the low BFU-E colony numbers in the cocultures expressing Wnt-10Bindicate that Wnt-10B expression has a negative effect on BFU-E progenitors that is dominant to the positive effect of Wnt-5Aand Wnt-2B expression. These data provide strong evidence that the activity of the three Wnt genes is not identical and that although they may share common targets and activities, each gene may also have activities that are distinct from each other.

The frequency of CD34+ cells was used to measure levels of progenitor/stem cells in a given cell population. Analysis of the CD34+ frequency of the cocultured hematopoietic cells provided additional evidence of biological activity of the Wntgenes. The CD34+ cell frequencies of the day 7 cocultures are shown in Fig 6D. Each Wnt-expressing coculture contained 1.4- to 1.8-fold higher frequencies of CD34+ cells than the CV-1 control. The coculture expressing all three Wnt genes had the highest frequency (mean, 11.4%) followed by the Wnt-10Bcoculture (mean, 9.2%), the Wnt-2B coculture (mean, 8.7%), and the Wnt-5A coculture (mean, 8.5%). These CD34+frequencies were similar to the cocultures containing SCF (mean, 9.0%) or IL-3 (mean, 7.2%) alone. The CV-1 control coculture contained the lowest CD34+ frequency (mean, 6.1%), indicating that theWnt-containing cocultures expand/retain a higher percentage of progenitor cells (CD34+) than the control.

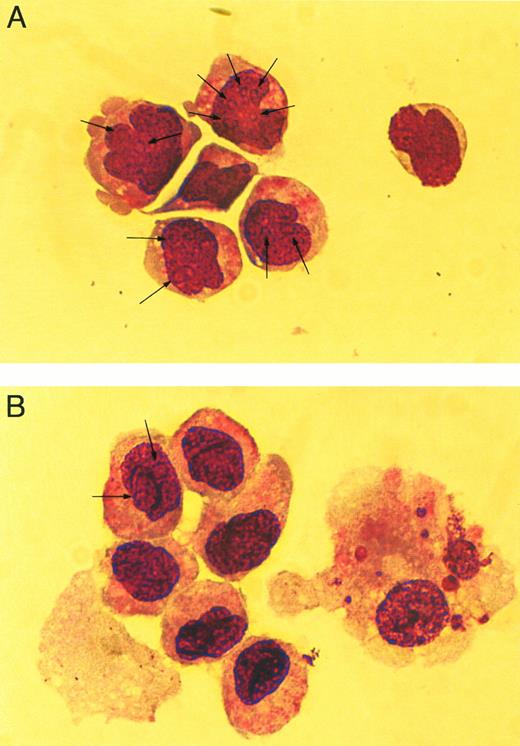

The cellular morphology of the cocultured hematopoietic cells was evaluated by examination of Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospin preparations. The hematopoietic cells cocultured in the presence ofWnt-expressing feeder cells contained a greater frequency of primitive hematopoietic cells and few mature cells (Fig 7A) compared to cocultures with CV-1 alone (Fig 7B). This difference is evident by the presence of numerous cells in the Wnt-expressing cocultures that contain nucleoli (Fig 7A, arrows) and noncondensed nuclei compared with the control where few cells have nucleoli, but most contain condensed nuclei (Fig7B). The presence of nucleoli and noncondensed nuclei are consistent with more primitive cells, whereas the absence of nucleoli and the presence of condensed nuclei are consistent findings of more mature cells. In addition, mature cells (Fig 7B, cell to the right) were often present in the control cultures, whereas very few were identified in the Wnt-expressing cocultures. Based on the results of the three assays, it is evident that the coculture withWnt-expressing feeder cells results in biological effects on hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells.

Cellular morphology of cocultured cells. Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of hematopoietic cells cocultured withWnt-expressing feeder cells (A) and with feeder cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector (B). All Wnt-expressing cocultures contained similar cellular morphology (data not shown) and are represented by a single sample. Arrows indicate nucleoli within the nucleus of stained cells. Cells were photographed under phase-contrast using a 63× objective.

Cellular morphology of cocultured cells. Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of hematopoietic cells cocultured withWnt-expressing feeder cells (A) and with feeder cells transduced with the MSCVneoEB vector (B). All Wnt-expressing cocultures contained similar cellular morphology (data not shown) and are represented by a single sample. Arrows indicate nucleoli within the nucleus of stained cells. Cells were photographed under phase-contrast using a 63× objective.

Expression of members of the fz family on hematopoietic cells.

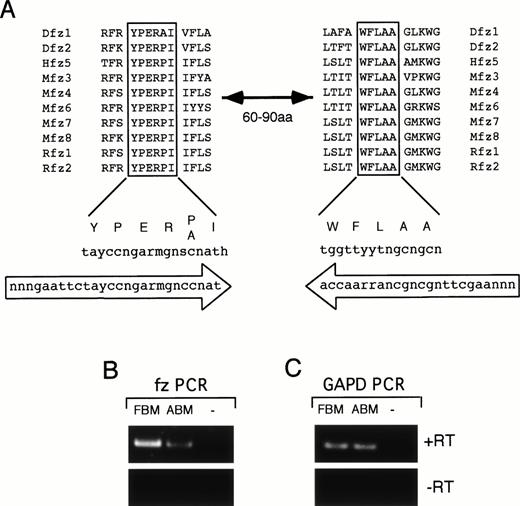

To further examine evidence for a role for members of the Wntgene family in human hematopoiesis we evaluated the expression of members of the fz gene family, which have been shown to be receptors for the Wnt ligand,31-33 in hematopoietic cells. Two highly conserved regions are present within all frizzled proteins described to date and are separated by 60 to 90 amino acids in different family members (Fig 8A). Degenerate PCR primers were designed to these regions and used for RT-PCR amplification of RNA isolated from CD34+ FBM (Fig8B, FBM) and CD34+ ABM (Fig 8B, ABM). A band of the correct size was detected in both populations, but not in a no-template control (−) or in controls lacking reverse transciptase (−RT) during the cDNA synthesis (Fig 8B). The band in the CD34+FBM sample was consistently stronger than the CD34+ ABM sample (Fig 8B and data not shown). In addition, no band was detectable in total FBM or total ABM by ethidium bromide staining (data not shown). This band was subcloned into the pGEM-T vector and 32 independent clones were sequenced. A total of six different fzgene fragments were identified in both CD34+ FBM and CD34+ ABM (HfzBM1-6) and the deduced amino acid sequence of each clone was compared with the Genbank database to identify homologous fz family members. Three of the fz gene fragments (HfzBM1, HfzBM2, and HfzBM4) are identical to known human frizzled genes (Hfz5, FZD3, and HUMFRIZ, respectively) and two (HfzBM3 and HfzBM6) are similar to other mammalian genes (Rfz1 and Mfz7, respectively) (Fig 9). One fz gene fragment (HfzBM5) shows only weak homology to a Zebrafish frizzled gene (Zgo4) and appears to be unique (Fig 9). The mouse ortholog of HfzBM6 (Mfz7) is expressed in fetal mouse hematopoietic tissues38; however, it is not known whether the other fz genes we have identified are expressed in mouse hematopoietic tissues. The identification of six members of the fz gene family in CD34+ FBM and CD34+ ABM provides additional evidence of a role for members of the Wnt gene family in human hematopoiesis.

Frizzled degenerate PCR. (A) Alignment of two highly conserved regions of fz proteins from Drosophila(Dfz), human (Hfz), mouse (Mfz), and rat (Rfz). These regions are separated by 60 to 90 amino acids in various family members. Consensus sequence for the aligned protein regions is shown below with corresponding codon sequence. Oligonucleotides used for the degenerate PCR are shown in large arrows indicating orientation of the primers. (B) RT-PCR results of fz degenerate primers on RNA from CD34+ FBM, CD34+ ABM, and a no-template control (−). Reverse transcription was performed with (+RT) or without (−RT) RT in the cDNA synthesis step. Equivalent amounts of RNA were used from each tissue for reverse transcription. One quarter of the cDNA was used for PCR amplification with the degenerate primers. (C) RT-PCR results using primers to GAPD. One quarter of the cDNA synthesized from FBM and ABM was PCR amplified using the GAPD primers. No product was observed in (B) and (C) for the no-template control or when RT was omitted from the reactions.

Frizzled degenerate PCR. (A) Alignment of two highly conserved regions of fz proteins from Drosophila(Dfz), human (Hfz), mouse (Mfz), and rat (Rfz). These regions are separated by 60 to 90 amino acids in various family members. Consensus sequence for the aligned protein regions is shown below with corresponding codon sequence. Oligonucleotides used for the degenerate PCR are shown in large arrows indicating orientation of the primers. (B) RT-PCR results of fz degenerate primers on RNA from CD34+ FBM, CD34+ ABM, and a no-template control (−). Reverse transcription was performed with (+RT) or without (−RT) RT in the cDNA synthesis step. Equivalent amounts of RNA were used from each tissue for reverse transcription. One quarter of the cDNA was used for PCR amplification with the degenerate primers. (C) RT-PCR results using primers to GAPD. One quarter of the cDNA synthesized from FBM and ABM was PCR amplified using the GAPD primers. No product was observed in (B) and (C) for the no-template control or when RT was omitted from the reactions.

Alignment of hematopoietic fz genes. Amino acid sequences of the isolated fz gene fragments (HfzBM1-6) were aligned to homologous sequences identified in Genbank. The identified homologs are human frizzled-5 (Hfz5; Genbank accession no. U43318 ), human frizzled homolog (FZD3; Genbank accession no. U82169), mouse frizzled-9 (Mfz9; Genbank accession no. AF033585), rat frizzled-1 (Rfz1; Genbank accession no. L02529), chicken frizzled-1 (Cfz1; Genbank accession no. AF031830), human frizzled-related gene (HUMFRIZ; Genbank accession no. L37882), rat frizzled-2 (Rfz2; Genbank accession no.L02530), Zebrafish frizzled gene (Zgo4; Genbank accession no. U49408), mouse frizzled-7 (Mfz7; Genbank accession no. U43320), and chicken frizzled-7 (Cfz7; Genbank accession no. AF031831). Identities are indicated by dots (•).

Alignment of hematopoietic fz genes. Amino acid sequences of the isolated fz gene fragments (HfzBM1-6) were aligned to homologous sequences identified in Genbank. The identified homologs are human frizzled-5 (Hfz5; Genbank accession no. U43318 ), human frizzled homolog (FZD3; Genbank accession no. U82169), mouse frizzled-9 (Mfz9; Genbank accession no. AF033585), rat frizzled-1 (Rfz1; Genbank accession no. L02529), chicken frizzled-1 (Cfz1; Genbank accession no. AF031830), human frizzled-related gene (HUMFRIZ; Genbank accession no. L37882), rat frizzled-2 (Rfz2; Genbank accession no.L02530), Zebrafish frizzled gene (Zgo4; Genbank accession no. U49408), mouse frizzled-7 (Mfz7; Genbank accession no. U43320), and chicken frizzled-7 (Cfz7; Genbank accession no. AF031831). Identities are indicated by dots (•).

DISCUSSION

Hematopoietic stem cells arise from the induction of ventral mesoderm.9,49-51 Studies from Xenopus have shown a multitude of genes involved in mesoderm induction, including members of the TGF-β superfamily, the FGF family, and the Wnt gene family.1 Previously, BMP-4 and TGF-β have been shown to play a role in hematopoiesis. BMP-4 induces hematopoiesis in embryoid bodies formed from mouse ES cells in vitro8 and stimulates GATA-2 expression in vivo.9 TGF-β has been shown to act as a bifunctional regulator of hematopoietic cellular activity because of its ability to either stimulate or inhibit hematopoietic progenitors. The findings in this report and by Austin et al38 support a role for members of the Wnt gene family in mammalian hematopoiesis.

In this study we have found that Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, andWnt-10B are expressed by BMSC and in FBM and ABM, but onlyWnt-5A was detected in CD34+Lin−primitive progenitors. The expression of Wnt-2B andWnt-10B in hematopoietic cell lines and in unfractionated BM, but not in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, indicates that they are likely expressed in committed progenitor cells and/or in mature cells. The secreted glycoproteins encoded by the Wnt genes have been shown to function as paracrine or autocrine signals46,47 that act locally due to the association of the proteins with the cell surface and extracellular matrix.23 24 In the BM microenvironment it is possible that the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells respond to the Wntproteins secreted by the stromal cells during cell-cell interactions in a paracrine fashion. As the HPC respond to the Wnt signals and additional factors within the microenvironment to commit to a specific lineage, differentiate, and exit the BM, their endogenous Wntgenes may be activated and produce an autocrine signal. Extensive analysis of the expression pattern of each Wnt gene in specific subpopulations of cells and the pattern of expression of the fzgenes should provide additional information on the extent of the role the Wnt genes play in hematopoiesis.

The biological activity of Wnt-5A, Wnt-2B, andWnt-10B was evaluated in a coculture system in which purified CD34+Lin− hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells were incubated on a fibroblastic feeder cell layer that was producing one or several Wnt proteins. This coculture system was designed to mimic the BM microenvironment by providing a stromal-like layer of cells that produces putative factors that act on hematopoietic cells. The progenitor levels measured in the cocultures from the Wnt-expressing cells provide evidence for a biological activity of Wnt expression on hematopoietic progenitors. Levels of CFU-MIX and cellular morphology of the cocultured cells are consistent with Wnt genes acting on a primitive multilineage progenitor. The magnitude of the Wnt activity can be evaluated by comparing the effects observed by coculturing cells in the presence of Wnt-expressing feeder cells and cocultures containing SCF or IL-3. CFU-MIX colony numbers are twofold to threefold higher in theWnt-expressing cocultures compared with either the SCF or IL-3 coculture. CFU-GM colony numbers are greater than the IL-3 coculture, but 50% to 70% of the levels in the SCF coculture. A similar pattern is observed with BFU-E where colony numbers in Wnt-5A andWnt-2B cocultures are greater than the IL-3 coculture, but less than the SCF coculture; however, the Wnt-10B coculture is much lower than any of the cocultures except for the CV1 control. These results indicate that the activity measured in the Wntexpressing cocultures is greater than the SCF– or IL-3–containing cocultures on multilineage progenitors, and is greater than IL-3, but less than SCF, on erythroid and myeloid progenitors. Based on these data, we have concluded that the Wnt genes are a new group of hematopoietic factors.

The role of Wnt genes in hematopoiesis is complicated by the expression of three members of the gene family in hematopoietic tissues that may have overlapping, but distinct, activity on hematopoietic cells. In the current study we have found that Wnt-10B has similar activity to Wnt-5A and Wnt-2B on mixed lineage progenitors and myeloid progenitors, but has a distinct activity on erythroid progenitors. This could be the result of differential expression of receptors on erythroid progenitors. Putative receptors for Wnt-5A and Wnt-2B may be present on erythroid progenitor cells, while a Wnt-10B receptor may be absent. Support for this hypothesis has been published recently by Yang-Snyder et al,32 who found that Rfz1 could bind xWnt-8, but not xWnt-5A. However, this difference may not be a result of differences in receptor expression, but could be the result of signaling through distinct pathways within erythroid progenitors. Receptors for each of the genes could be present on erythroid progenitor cells, but the binding of Wnt-5A or Wnt-2Bcould activate one or similar pathways, while the binding ofWnt-10B could activate a separate and distinct pathway. Our data are consistent with the second hypothesis because the expression of Wnt-10B reduces BFU-E progenitor numbers in a dominant manner. If the differential activity on BFU-E progenitors were the result of differences in receptor expression, then coculture with all three Wnt genes should be similar to coculture withWnt-5A or Wnt-2B.

Differences in receptor expression will play a significant role in elucidating the effects of the Wnt genes on hematopoietic cells. The specificity of each Wnt gene for different receptors will provide another level of complexity because some Wntproteins can bind multiple receptors and each receptor can bind multiple Wnt proteins.31 In addition, the signaling associated with binding of a Wnt protein to its putative receptor could be distinct in a mixed lineage progenitor cell than in a committed progenitor cell or during differentiation into a mature cell. These different levels of complexity will require further studies addressing signal transduction of the Wnt genes and identification of Wnt protein/receptor interactions within hematopoietic cells. Furthermore, the interaction of the Wntgenes with other hematopoietic factors will provide valuable information on the basis for the biological activity of Wntgenes on hematopoietic cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the assistance of John Brandt with analyzing methylcellulose cultures and Annette Bruno with DNA sequencing. Additional thanks to Kiranur Subramanian for his gift of CV-1 cells and Igor Roninson and the Department of Genetics at the University of Illinois at Chicago for use of their irradiator. We also thank Leonidas Platanias for critical review of the manuscript.

Supported in part by a generous gift from the W.M. Keck Foundation.

Address reprint requests to David J. Van Den Berg, PhD, University of Illinois at Chicago, Division of Hematology/Oncology (M/C 734), 900 S Ashland Ave, Room 3150 MBRB, Chicago, IL 60607; e-mail: dvdb@uic.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.