Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are large granular lymphocytes capable of destroying cells infected by virus or bacteria and susceptible tumor cells without prior sensitization and restriction by major histocompatability complex (MHC) antigens. Their cytotoxic activity could be strongly enhanced by interleukin-2 (IL-2). Previous findings, even if obtained with indirect experimental approaches, have suggested a possible involvement of the inducible nitric oxide (iNOS) pathway in the NK-mediated target cell killing. The aim of the present study was first to directly examine the induction of iNOS in IL-2–activated rat NK cells isolated from peripheral blood (PB-NK) or spleen (S-NK), and second to investigate the involvement of the iNOS-derived NO in the cytotoxic function of these cells. Our findings clearly indicate the induction of iNOS expression in IL-2–activated PB-NK and S-NK cells, as evaluated either at mRNA and protein levels. Accordingly, significantly high levels of iNOS activity were shown, as detected by the L-arginine to L-citrulline conversion in appropriate assay conditions. The consequent NO generation appears to partially account for NK cell-mediated DNA fragmentation and lysis of sensitive tumor target cells. In fact, functional inhibition of iNOS through specific inhibitors, as well as the almost complete abrogation of its expression through a specific iNOS mRNA oligodeoxynucleotide antisense, significantly reduced the lytic activity of IL-2–activated NK cells. Moreover, IL-2–induced interferon-γ production appears also to be dependent, at least in part, on iNOS induction.

NATURAL KILLER (NK) cells are a distinct subset of CD3− CD16+ CD56+large granular lymphocytes (LGL), which possess the ability to mediate major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-unrestricted cytolytic activity against cells infected by viruses or bacteria, transplanted cells, and neoplastic cells.1 Cytotoxic factors, contained in the granules and released from the NK cell after interaction with the target cell through mutual surface receptors, mainly include perforin and granzymes, able to induce both membrane and DNA damage in the target cells.2,3 Moreover, murine NK cells and FcγR-stimulated human NK cells have been reported to express Fas ligand and kill Fas (CD95/APO-1)-expressing targets.4,5 The functions of NK cells, as well as their maturation and differentiation, are regulated by various stimuli, including interleukin-2 (IL-2).6 Resting NK cells can respond directly to IL-2 with enhanced cytotoxic activity and eventually proliferation, with no additional requirement for other activating stimuli. IL-2 augments mRNA expression for perforin and interferon-γ (IFN-γ),7,8 as well as synthesis and expression of various adhesion molecules on NK cells,9 which increase their cytotoxic potential. In vitro long-term culture of NK cells in the presence of high doses of IL-2 leads to the generation of cells with a broad range of tumor target cell lysis (lymphokine-activated killer [LAK] activity).6Interestingly, generation of LAK activity has been previously reported to depend on nitric oxide (NO) production.10-14 Indeed, both in vivo and in vitro IL-2 treatment, able to markedly stimulate NK cell tumoricidal activity, correlates with increased NO production determined as nitrite levels in serum or culture medium.10-14 Moreover, the inhibition of NO synthesis blocks IL-2–induced NO production and significantly reduces IL-2–induced NK cytotoxicity, thus suggesting that NO synthesis may contribute to IL-2–induced antitumor responses of NK cells. Moreover, NKR-P1A triggering, which is known to induce NK cell activation and mediate reverse antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC),15,16 is able to induce nitric oxide synthase (NOS) activity.10 Of note, evidence has been recently reported that genetic deletion of functional inactivation of NOS2 (inducible NOS [iNOS]) in mice abolished NK cell responses, thus providing the first evidence that iNOS-derived NO is a prerequisite for the development of NK cytotoxicity in vivo.17 Expression of NOS2 seems to be essential for at least four key elements of the innate immune response: (1) prevention of the microbial dissemination; (2) responsiveness of NK cells to the NK cell-activating factor, IL-12; (3) release by NK cells of IFN-γ; and (4) suppression by IFN-γ of the production of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), a potent NOS2-suppressing cytokine.17 18

NO, a small lipophilic molecule enzymatically generated from cleavage of terminal guanidino nitrogen from L-arginine by a family of NOS, takes part in several biologic events.19,20 Constitutive and inducible isoforms of the NOS exist, and they differ in structure and regulation.18,21 All of the isoforms convert arginine to citrulline and NO and require nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) as a cofactor.22 Constitutive isoforms of NOS (cNOS) produce small amounts of NO over several minutes in response to agonists that elevate intracellular Ca2+. The cytokine-inducible, or inflammatory, NOS (iNOS, NOS2) produces NO in a sustained manner independently of intracellular calcium elevations and is expressed mainly in inflammatory conditions. Cell-mediated immune responses are considered as classical NO-mediated actions.18,22 In particular, activation of the NO system mediates macrophage cytotoxicity as a first line of defense against invading pathogens or tumor cells and elicits apoptotic cell death in different cellular systems.23 NO-induced inhibition of iron-sulphur enzymes involved in cellular energy supply, as well as NAD(H)-dependent modification of protein thiols24 or direct DNA damage25,26 have been implicated in the cytotoxic NO signaling, or in the apoptogenic action of NO. Interestingly, the susceptibility of iNOS-deficient mice to several bacterial and viral infections, as well as to the growth of several implantable tumors is greatly increased compared with wild-type mice.23,27 28

Here, we show direct evidence for the induction of iNOS expression and activity in IL-2–activated peripheral blood and splenic rat NK cells. Our findings also indicate that NO represents an effector molecule that contributes to the tumoricidal activity of IL-2–stimulated NK cells and is involved in the IFN-γ production from these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Fisher F344 rats (5 to 6 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Calco, Como, Italy).

Reagents.

The following mouse monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) were used: OX19, which identifies CD5, a pan-T surface antigen; MCA1427 (Serotec, Oxford, UK), an IgG1 that recognizes rat CD161 protein, also known as NKR-P1A, a 60-kD disulfide-linked dimer composed of two 30-kD subunits expressed on rat NK cells; a F(ab′)2 preparation of goat antiserum to mouse Ig was purchased from Cappel Laboratories (Cochranville, PA); MCA 341, an IgG1, which specifically identifies rat monocytes and macrophages by recognizing a 97-kD antigen (ED1) predominantly located intracellularly (although membrane expression also occurs), and MCA1427RPE, a mouse anti-rat CD161-R-phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated MoAb; were purchased from Serotec. Human recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2) was from EuroCetus B.V. (Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Anti-iNOS MoAb purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) was directed against a protein fragment (961-1144 aa) of mouse macNOS. L-nitro-monomethylarginine (L-NMMA), aminoguanidine (AG), and N-(4-aminobutyl)-5-chloro-2-naphthalenesulfonamide (W13) were from Alexis Biochemicals (Laufelfingen, Switzerland). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA) and recombinant rat IFN-γ was from Endogen (Cambridge, MA). Sodium nitroprussiate (SNP) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Isolation of peripheral blood NK cells (PB-NK).

Mononuclear cells were separated from cardiac-puncture–obtained heparinized peripheral blood by Lymphoprep gradient centrifugation (Nicadem, Oslo, Norway), further purified by passage through a nylon wool column (Cellular Products, Buffalo, NY), plastic adherence to remove monocytes, Percoll (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) density gradient fractionation, and panning on plastic dishes (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) as previously described.29Isolated PB-NK were then cultured over 18 hours at 37°C, in 5% CO2 in air in the presence of rIL-2 (100 U/mL) before analysis of iNOS expression and enzymatic activity, and cytotoxicity studies.

Cytofluorymetric analysis.

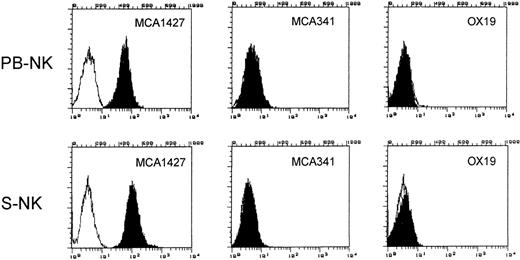

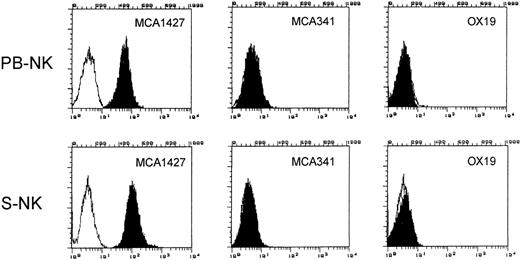

The surface phenotype of LGL population was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence labeling and cytofluorimetry on FACS II Analyzer (Becton Dickinson) by using MCA1427 (anti-CD161), OX19, and MCA 341 MoAbs. Unpermeabilized cells were used for MCA1427 and OX19 staining. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG F(ab′)2 fragment was used as secondary antibody (GαM). MCA 341 staining was performed on permeabilized cells. Briefly, cells were washed with 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 4% fetal calf serum (FCS), resuspended at 5 × 106/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and permeabilized with methanol 70% for 5 minutes on ice. After confirming the adequacy of permeabilization by trypan blue uptake, cells were pelletted and resuspended in PBS containing saturating concentration of MCA 341 MoAb. The results presented in Fig 1 show that the NK cell population purified as above described, was >99% MCA1427+ OX19− MCA 341−. The absence of contaminating monocytes was also confirmed by negative staining for nonspecific esterase (data not shown).

Phenotypic analysis of PB-NK and S-NK cells. Phenotype of purified NK cells was analyzed by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry using the indicated MoAbs to determine the purity of the cell populations used in this study. White area represents staining with secondary antibody alone.

Phenotypic analysis of PB-NK and S-NK cells. Phenotype of purified NK cells was analyzed by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry using the indicated MoAbs to determine the purity of the cell populations used in this study. White area represents staining with secondary antibody alone.

Spleen-NK cell (S-NK) purification.

S-NK cells were obtained as previously described.30Briefly, spleens were aseptically removed and single-cell suspensions were prepared in RPMI 1640 with 5% FCS. Mononuclear cells obtained by centrifugation on Ficoll/Hypaque gradients were incubated on plastic tissue culture flasks in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1 hour. The nonadherent cells were further passed through nylon-wool columns and then cultured at 2 × 106/mL in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 5 × 10−5 mol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, streptomycin, and penicillin and containing 500 U/mL rIL-2. After 48 hours of incubation at 37°C, in 5% CO2 in air, the adherent cells were washed with prewarmed medium, starved for 48 hours (control cells) and cultured in the absence or presence of IL-2 (100 U/mL) for an additional 96 hours. The phenotype of S-NK cells was routinely >99% MCA1427+ OX19−MCA341− as assessed by flow cytofluorimetric analysis on FACS II Analyzer (Fig 1).

Nitrite levels.

In aqueous solution, NO reacts rapidly with O2 and accumulates in the culture medium as nitrite and nitrate ions. After indicated incubation times, 100-μL samples of the culture supernatants were removed for nitrite measurement. Nitrite concentrations were quantified by a colorimetric assay based on the Griess reaction.31 Briefly, 100 μL of culture supernatant were mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent in a U-well microtiter plate and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. The optical density (OD) was measured at 550 nm using a micro-ELISA reader (MultiSkan Plus; DASIT, Milan, Italy) using NaNO2 as a standard and Dulbecco’s medium supplemented with 10% FCS as a blank.

Determination of NOS activity.

NOS activity was determined by measuring the conversion of [3H]-L–arginine to [3H]-L–citrulline as previously described.32 Cells were homogenized by sonication in homogenization ice-cold buffer (25 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA) containing protease inhibitors (0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL leupeptin). The homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C for 20 minutes at 15,000 rpm. The supernatants were passed through an AG50WX-8 Dowex resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Melville, NY) to remove endogenous arginine. The protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid procedure (BCA; Pierce, Rockford, IL) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard. Enzymatic reactions were conducted at 37°C for 30 minutes in 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 1 mmol/L CaCl2, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 6 μmol/L tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), 2 μmol/L flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), 2 μmol/L flavin adenine mononucleotide (FAM), 1 mmol/L L-citrulline (to inhibit the catabolism of [3H]-L–citrulline, 60 mmol/L L-valine, 60 mmol/L L-ornithine, 60 mmol/L L-lysine (to inhibit nonspecific arginase activity), and 10 μCi/mL of [3H]-L–arginine (Amersham, Bukinghamshire, UK). Where indicated, CaCl2 (0.6 mmol/L) and calmodulin (CAM) (0.1 μmol/L) were added to the assay system. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.4 mL of stop buffer (50 mmol/L Hepes, pH 5.5, 5 mmol/L EDTA). Citrulline was determined by applying the samples to columns containing 0.1 mL of Dowex AG50WX-8, equilibrated resin to the Na+ form, to bind all of the unreacted, radiolabeled L-arginine. The columns were vortexed and centrifuged (15,000 rpm for 30 seconds). One hundred microliters of the eluate was counted by liquid scintillation to quantitate the formation of [3H]-L–citrulline. This assay measures both the calcium-dependent (constitutive) and the calcium-independent (inducible) isoenzymes. Any activity detected in the absence of Ca/CAM and in the presence of the CAM antagonist W13 (100 μmol/L) (to inhibit endogenous CAM) represented iNOS activity. iNOS activity was also considered inhibited by AG.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) amplification.

Total RNA was isolated from both PB-NK and S-NK cells after incubation for the indicated times in the absence or presence of IL-2, using the method of Chomczynski and Sacchi.33 A total of 200 ng RNA was incubated with 2.5 mmol/L random hexamers, 1 mmol/L each deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 2.5 U/mL Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), and 5 mmol/L MgCl2 in 20 mL of RT buffer (50 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.3) at 42°C for 20 minutes. After denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, the synthesized cDNA was subjected to a 35-cycle PCR, each cycle consisting of 1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 60°C, and 2 minutes at 72°C. The 5′ antisense primer corresponded to nucleotides 2698-2720 of the murine macrophage iNOS cDNA sequence, (Primm USA Inc, Andover, MA) and the 3′ sense primer to nucleotides 2941-2963. For comparison, β-actin transcripts were PCR-amplified from the same sample RNA using primers to nucleotides 2406-2423 (sense) and to nucleotides 2726-2708 (antisense) (Primm). The PCR mix contained 20 pmol of each primer, 200 mmol/L of each dNTP, and 2.5 U Taq polymerase (AmpliTaq; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, CT) in 100 μL of RT buffer with 2 mmol/L MgCl2. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Analysis of iNOS protein expression.

The expression of iNOS protein was assessed by flow cytometry and Western blotting using a specific anti-mouse macNOS MoAb. Briefly, for flow cytometry, the cells were fixed for 5 minutes at room temperature with paraformaldehyde (4% in PBS), permeabilized with 0.05% Nonidet P-40 in PBS, and then stained using 1 μg/106 cells of the relevant primary antibody (20 minutes at 4°C) and a fivefold excess of FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (DAKO, Milan, Italy). The fluorescence background was calculated in the absence of the primary antibody. An irrelevant primary antibody was used as negative control. In some experiments, two-color cytofluorographic analysis was performed using mouse anti-rat CD161-PE MoAb and mouse specific anti-mouse macNOS MoAb and FITC-conjugated GαM. For Western blot analysis, cell pellets were washed with ice-cold PBS and then solubilized for 15 minutes in a lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 (vol/vol), 10% glycerol, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L Na3VO4, 4 mmol/L PMSF, 20 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 5 mmol/L EGTA, 2 μg/mL leupeptin, 2 μg/mL aprotinin, 2 μg/mL pepstatin, 50 mmol/L Hepes, pH 7.5. The lysates were clarified by centrifugation (15,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C), and the protein content assayed by the bicinchoninic acid procedure (BCA, Pierce). After addition of sodium dodecyl sulphate and β-mercaptoethanol, the samples were boiled and 250 μg of protein/lane were loaded into the slots of 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gels, which were run as described elsewhere.34 As an internal control for iNOS, 70 μg of cell lysates from rat peritoneal macrophages treated with IFN-γ (100 U/mL) plus LPS (100 ng/mL) for 18 hours, were loaded into the same gel. High efficiency transfer of proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes was performed at 200 mA for 18 hours in a buffer containing 25 mmol/L Tris, 192 mmol/L glycine, 20% methanol, pH 8.3. After transfer, both the gels and the blots were routinely stained with Ponceau red. The nitrocellulose sheets were processed at room temperature, first 1 hour with PBS + 3% BSA, then for 2 hours with the anti-iNOS MoAb (1:500 dilution) in an incubation buffer containing 150 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 5% powdered milk, pH 7.4. After washing five times for 5 minutes with the incubation buffer, the blotted bands were incubated with the relevant horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG for 1 hour in the same buffer. After extensive washing, immunostaining was recorded photographically, using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit from Amersham.

Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide treatment in vitro.

Antisense (AS) oligodeoxynucleotide targeting a conserved sequence within the open reading frame of the cDNA encoding iNOS was designed to produce selective knock-down of this enzyme, as previously described.35 The published cDNA transcript to the rat macrophage (GenBank accession no. M84373) was used to synthesize 21-nucleotide oligodeoxynucleotide. The phosphorothioated oligodeoxynucleotide was synthesized in an automatic solid-phase DNA synthesizer (Primm). We targeted a conserved sequence, nucleotides 1829-1809, which is homologous in mouse and rat macrophage iNOS (AS: CTT CAG AGT CTG CCC ATT GCT). To account for possible aspecific effects of oligodeoxynucleotide, a scrambled sequence was used as control (Scrambled [Scr]: TCT CAG TGA GCC CTC ATT CTG). Both PB-NK cells and S-NK cells were treated with either oligomer for 18 and 96 hours, respectively, at the concentration of 20 μmol/L in RPMI medium. Neither oliogodeoxynucleotide was cytotoxic as determined by trypan blue exclusion (95% viability).

Tumor cell lines.

The NK-sensitive target cells, YAC-1 cell line, a subclone of a Moloney leukemia virus-induced tumor in A/Sn mice, and the LAK-sensitive target cells, P815, a chemically induced NK-resistant mastocytoma, were maintained by continuous in vitro culture in complete medium, which consisted of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, streptomycin, and penicillin.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity assay was performed by incubating serial dilutions of effector cells with 5 × 103 51Cr-labeled (Na251CrO4; New England Nuclear [NEN], Boston, MA) target cells YAC-1 and P815 cells in triplicate wells of round-bottomed microtiter plates (Sterilin Teddington, Middlesex, UK) in a final volume of 0.2 mL. After 4 hours of incubation, the plates were centrifuged, and 0.1 mL supernatant was removed and counted. The percentage of specific 51Cr release was calculated as follows: 100 × (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release). Where indicated, the cytotoxicity assay was performed with NK cells pretreated with AS or Scr oligonucleotides as above described or in the presence of the NOS inhibitors, L-NMMA (500 μmol/L) and aminoguanidine (50 μmol/L). Inhibitors had no effect on target cell viability (>90% viability by trypan blue exclusion) or spontaneous51Cr release (not shown).

JAM test.

The analysis of apoptosis in target cells (YAC-1 and P815) after coculture for 4 hours with PB-NK or S-NK cells, was performed as previously described.36 Briefly, effectors or targets cells were pulsed for 18 hours with 2 mCi/mL 3H-thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol; NEN), washed, and then incubated either alone or with unlabeled target or effector cells, respectively, at effector/target (E/T) ratios reported in the figure legends. At the end of the culture, the cells were harvested on a glass fiber filter, and3H-thymidine present on the filters was measured by liquid scintillation counting. The results were expressed as the arithmetic means cpm ± standard deviation (SD) of five replicate cultures. The percentage of fragmented DNA was calculated as follows: 100 × (mean cpm cells cultured alone − mean cpm cells cultured with target cells/mean cpm cells cultured alone).

DNA agarose gel electrophoresis.

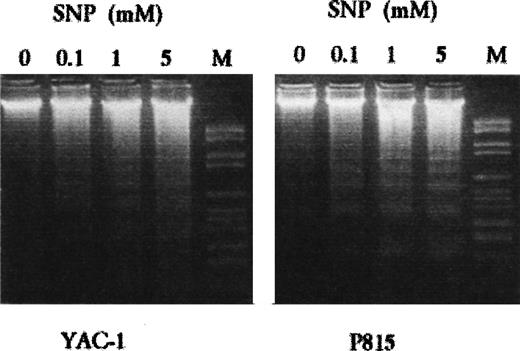

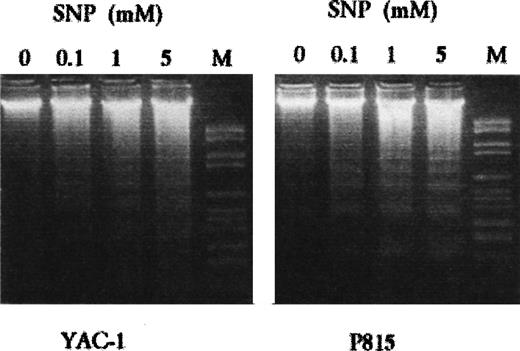

The susceptibility of target cells (YAC-1 and P815) to undergo apoptosis in the presence of a NO donor at different doses (SNP, 0.1 to 5 mmol/L) was evaluated through DNA laddering detection. Cells (5 × 106), after the indicated treatments, were harvested, washed, and incubated in 0.3 mL of 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 8.0 containing 25 mmol/L EDTA, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% SDS, and 0.1 mg/mL proteinase K at 37°C for 18 hours. After phenol-chloroform extraction, the DNA was ethanol precipitated and resuspended in Tris-EDTA (TE: 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6 and EDTA 1 mmol/L, pH 8), incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with 1 mg/mL RNAse and applied on a 1.8% agarose gel, and electrophoresed for 2 hours at 100 V.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of IFN-γ.

IFN-γ levels released from treated NK samples were determined with the BioSource International Cytoscreen rat IFN-γ ELISA (BioSource Int, Inc, Camarillo, CA). Wells of ELISA plates were coated with an antibody specific for rat IFN-γ, after which 100 μL of supernatants from purified PB- or S-NK cells (2 × 106/mL) cultured with or without IL-2 in the presence or absence of NOS inhibitors, were added to each well. The IFN-γ content was determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions and expressed as pg/106 cells.

RESULTS

Stimulation of NO release by IL-2 treatment is due to the induction of iNOS enzyme.

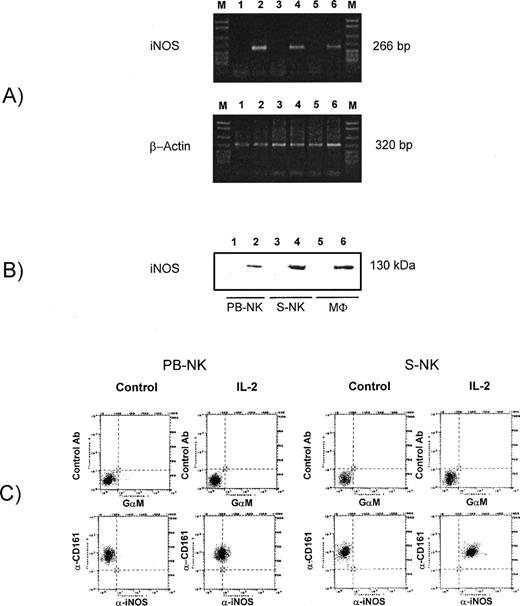

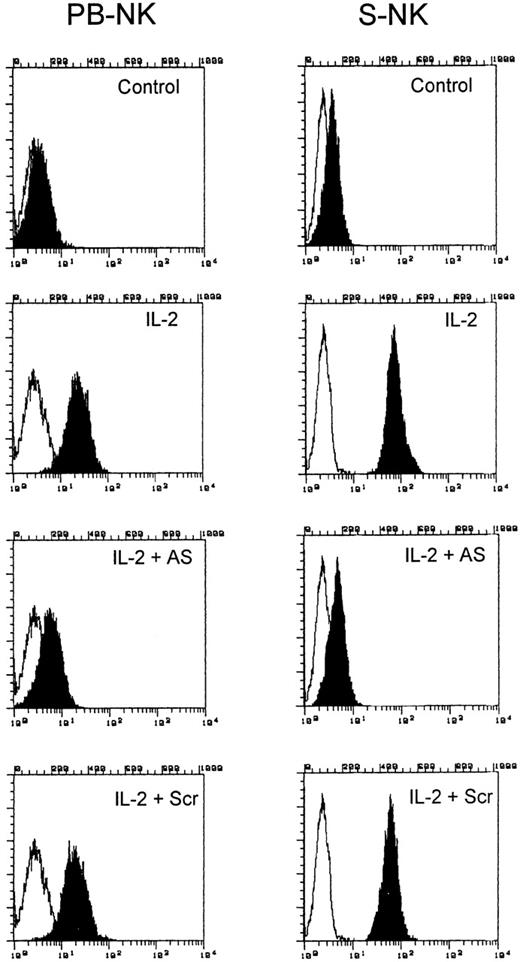

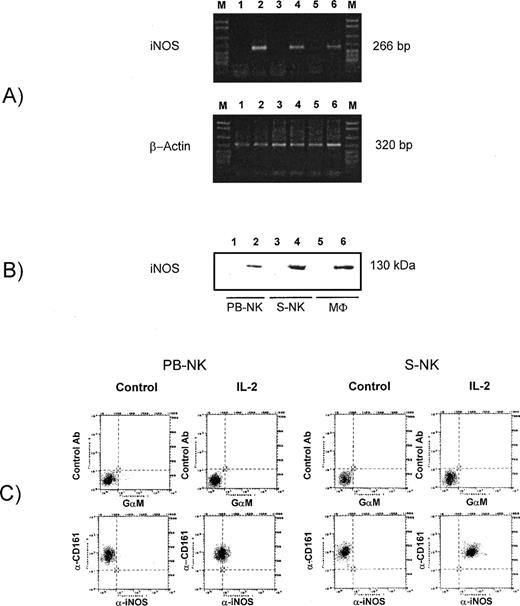

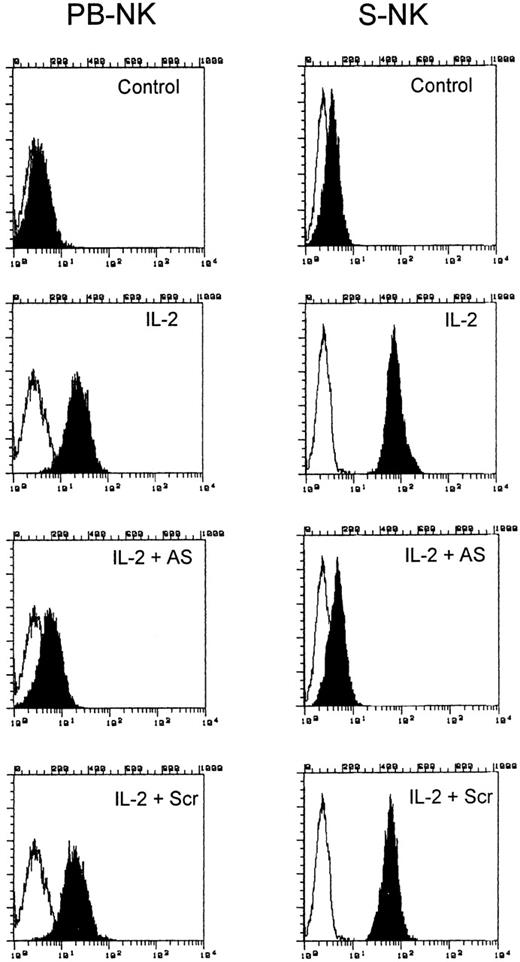

A significant induction of NO generation from IL-2–treated NK cells compared with untreated cells was observed, as assessed by nitrite determination in culture medium, confirming our original observations10 (and data not shown). To assess whether stimulation of NO release after IL-2 treatment was due to an induction of iNOS or to cNOS activity, we performed enzyme activity assays based on the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline in appropriate conditions allowing the detection of both constitutive and inducible isoenzyme activity on cell sonicates. Table1 illustrates the NOS activity in extracts from PB-NK and S-NK cells after incubation with rIL-2 for 18 hours or 96 hours, respectively. IL-2 significantly increased (P < .001) citrulline generation in both PB-NK and S-NK cells. This event could be attributed to iNOS, but not cNOS activity, as it was not affected by the absence of Ca/CAM and the presence of the CAM antagonist W13. Moreover, IL-2–induced iNOS activity was inhibited by both L-NMMA, a NO synthesis inhibitor and AG, a relatively specific inhibitor of the inducible form. The treatment of control cells with NOS inhibitors alone did not influence the citrulline basal levels. The analysis of iNOS expression at mRNA and protein levels in IL-2–treated NK cells, definitively established that NO generation was due to the induction of iNOS at transcriptional and translational levels (Fig 2). The RT-PCR of mRNA isolated from both PB-NK and S-NK cells cultured in the presence of rIL-2 for 18 or 96 hours, respectively, resulted in the amplification of an iNOS-specific cDNA fragment (Fig 2A, lanes 4 and 6). This fragment corresponded to the 266-bp PCR product obtained after RT-PCR of mRNA from rat macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ plus LPS for 18 hours (Fig 2A, lane 2). No evidence of iNOS mRNA was observed in untreated cells (Fig 2A, lanes 1, 3, and 5). No PCR product was amplified in PCR reactions from samples not treated with reverse transcriptase (data not shown). The protein analysis confirmed the induction of iNOS in IL-2–treated NK cells, indicating that the iNOS gene transcription was followed by an effective translation of iNOS mRNA. As shown in Fig 2B, iNOS protein, which was undetectable in untreated cells, was highly expressed after treatment of both PB-NK and S-NK cells with IL-2 for 18 and 96 hours, respectively (lanes 1 through 4). Also in this case, lysates from rat macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ plus LPS were used as control. The induction of iNOS protein in IL-2–treated PB-NK cells and S-NK cells was also confirmed by immunofluorescence and cytofluorimetric analysis staining permeabilized cells with a specific anti-iNOS MoAb (Fig 2C). The percent of iNOS-positive cells greatly increased in CD161 positive cells on IL-2 treatment in both PB-NK and S-NK cell populations. In Fig 3 are also reported the cytofluorymetric analysis of iNOS after treatment with antisense oligodeoxynucleotide against iNOS mRNA. It is evident that iNOS-antisense treatment almost completely inhibited iNOS expression in both IL-2–activated PB-NK and S-NK cells, whereas the scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide was ineffective.

Analysis of iNOS expression in PB-NK and S-NK cells. (A) Expression of iNOS mRNA in PB-NK and S-NK cells after treatment with IL-2. The mRNA of stimulated and unstimulated cells was isolated and after RT-PCR was performed with specific primers for iNOS and β-actin. Lane 1, untreated rat peritoneal macrophages; lane 2, rat peritoneal macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ plus LPS for 18 hours; lane 3, control S-NK cells; lane 4, S-NK treated with IL-2 for 96 hours; lane 5, untreated PB-NK; lane 6, PB-NK treated with IL-2 for 18 hours. Size marker: DNA molecular weight marker VI (Boehringer) (M). Data show one representative experiment of three. (B) Western blot analysis with specific anti-iNOS MoAb in 200 μg of total cell lysates obtained from PB-NK cells or S-NK. As internal control for iNOS, 50 μg of rat peritoneal macrophage lysates were loaded into the same gels. Lane 1, untreated PB-NK; lane 2, PB-NK treated with IL-2 for 18 hours, lane 3, control S-NK cells; lane 4, S-NK treated with IL-2 for 96 hours; lane 5, untreated rat peritoneal macrophages; lane 6, rat peritoneal macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ plus LPS for 18 hours. (C) iNOS expression on CD161 positive PB- and S-NK cells after treatment with IL-2 as above described. Two-color cytofluorographic analysis was performed using mouse anti-rat CD161–PE MoAb and mouse specific anti-mouse macNOS MoAb and FITC-conjugated GM. As control antibodies, anti-human CD56-PE MoAb and GM-FITC MoAb were used.

Analysis of iNOS expression in PB-NK and S-NK cells. (A) Expression of iNOS mRNA in PB-NK and S-NK cells after treatment with IL-2. The mRNA of stimulated and unstimulated cells was isolated and after RT-PCR was performed with specific primers for iNOS and β-actin. Lane 1, untreated rat peritoneal macrophages; lane 2, rat peritoneal macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ plus LPS for 18 hours; lane 3, control S-NK cells; lane 4, S-NK treated with IL-2 for 96 hours; lane 5, untreated PB-NK; lane 6, PB-NK treated with IL-2 for 18 hours. Size marker: DNA molecular weight marker VI (Boehringer) (M). Data show one representative experiment of three. (B) Western blot analysis with specific anti-iNOS MoAb in 200 μg of total cell lysates obtained from PB-NK cells or S-NK. As internal control for iNOS, 50 μg of rat peritoneal macrophage lysates were loaded into the same gels. Lane 1, untreated PB-NK; lane 2, PB-NK treated with IL-2 for 18 hours, lane 3, control S-NK cells; lane 4, S-NK treated with IL-2 for 96 hours; lane 5, untreated rat peritoneal macrophages; lane 6, rat peritoneal macrophages stimulated with IFN-γ plus LPS for 18 hours. (C) iNOS expression on CD161 positive PB- and S-NK cells after treatment with IL-2 as above described. Two-color cytofluorographic analysis was performed using mouse anti-rat CD161–PE MoAb and mouse specific anti-mouse macNOS MoAb and FITC-conjugated GM. As control antibodies, anti-human CD56-PE MoAb and GM-FITC MoAb were used.

Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of iNOS in PB-NK and S-NK cells treated with IL-2 in the presence or absence of iNOS-antisense. AS, antisense oligodeoxynucleotide against iNOS mRNA; Scr, scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide. Fluorescence intensity of permeabilized cells stained with an irrelevant primary antiody plus a secondary antibody was not significantly different from that incubated only with the secondary antibody (not shown). Results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

Flow cytometric analysis of the expression of iNOS in PB-NK and S-NK cells treated with IL-2 in the presence or absence of iNOS-antisense. AS, antisense oligodeoxynucleotide against iNOS mRNA; Scr, scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide. Fluorescence intensity of permeabilized cells stained with an irrelevant primary antiody plus a secondary antibody was not significantly different from that incubated only with the secondary antibody (not shown). Results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

iNOS induction is involved in the IL-2–activated NK cytotoxic functions.

To assess whether iNOS induction could be involved in the cytotoxic functions of IL-2–activated NK cells, we analyzed the effect of iNOS inhibition on 51Cr release and DNA fragmentation of target cells (YAC-1 as NK-sensitive cells and P815 as LAK-sensitive cells) after 4 hours incubation with PB-NK or S-NK cells at different E/T ratios at 37°C. With increasing numbers of either PB- or S-effector cells, there was a concomitant increase in both specific51Cr release and specific DNA fragmentation of YAC-1 target cells. The inhibition of iNOS activity through treatment with pharmacological inhibitors such as L-NMMA or AG or the almost total abrogation of its expression with a specific AS oligonucleotide, markedly decreased the cytotoxic activity of IL-2–stimulated-PB-NK (Table 2) and -S-NK cells against YAC-1 targets (Table 3); the scrambled oligodeoxynucleotide used as control was without effect. Similar results were obtained when P815 cells were used as target sensitive to IL-2–activated S-NK cell-mediated lysis (not shown). The susceptibility of target cells to undergo apoptosis in the presence of the NO donor SNP is shown in Fig 4. Overall, these results indicate that the IL-2–mediated induction of iNOS is involved in the cytotoxic functions of NK cells against tumor target cells.

SNP-induced DNA fragmentation in YAC-1 and P815 cells. The cells were incubated for 18 hours with SNP at indicated doses, after which extracted DNA was electrophoresed on 1.8% agarose gel as described in Materials and Methods.

SNP-induced DNA fragmentation in YAC-1 and P815 cells. The cells were incubated for 18 hours with SNP at indicated doses, after which extracted DNA was electrophoresed on 1.8% agarose gel as described in Materials and Methods.

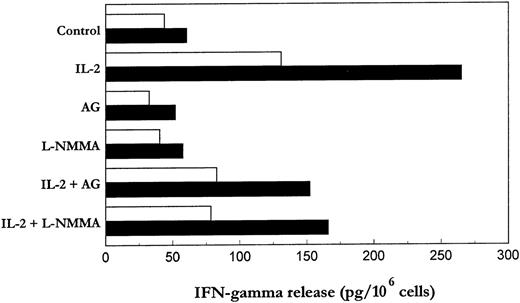

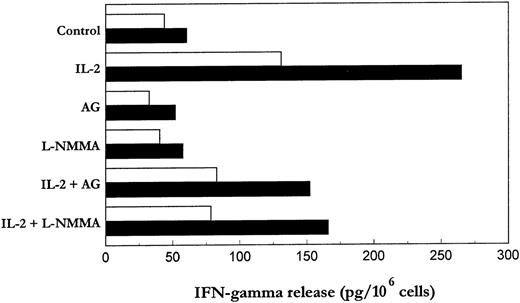

IL-2–induced IFN-γ secretion from NK cells is strongly reduced in the presence of iNOS inhibitor.

NK cells have a dual role as effector in innate resistance and regulatory in innate resistance, antigen-specific adaptive immunity and hematopoiesis.37-39 The regulatory functions of NK cells are probably more dependent on their ability to produce lymphokines, particularly IFN-γ, than on their cytotoxic activity.37We asked whether the regulation of NK cells by iNOS inhibitors involves IFN-γ production by these cells. As shown in Fig 5, stimulation of purified PB-NK and S-NK with IL-2 resulted in a marked induction of IFN-γ, which in turn was significantly reduced (about 40% to 45%) in the presence of AG or L-NMMA. These results suggest that IL-2–induced NO generation may be partly induced in the control of IFN-γ production triggered by this cytokine.

Effect of iNOS inhibitors on IL-2–induced IFN-γ production by PB- and S-NK cells. PB-NK and S-NK cells were incubated with or without IL-2 for 18 (□) or 96 hours (▪), respectively, in the presence or absence of AG (10 μmol/L) or L-NMMA (500 μmol/L). After incubation, cell-free supernatants were collected and IFN-γ levels quantitated by ELISA.

Effect of iNOS inhibitors on IL-2–induced IFN-γ production by PB- and S-NK cells. PB-NK and S-NK cells were incubated with or without IL-2 for 18 (□) or 96 hours (▪), respectively, in the presence or absence of AG (10 μmol/L) or L-NMMA (500 μmol/L). After incubation, cell-free supernatants were collected and IFN-γ levels quantitated by ELISA.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide the first direct evidence that in response to IL-2, both rat PB- and S-CD161 positive NK cells express iNOS at the mRNA and protein levels. The induction of iNOS expression was more significant in S-NK cells when compared with PB-NK cells likely due to the longer IL-2 activation (96 hours v 18 hours, respectively), in accordance with our previous findings indicating the time-dependent increasing NOS activity in IL-2–activated NK cells.10 This event is associated with a significant NO generation, which partially mediates cytotoxic activity of IL-2–activated-NK cells indicating that NK cells may cause target cell killing through both NO-dependent and -independent processes. Indeed, the functional inactivation of iNOS through AG or L-NMMA or the abrogation of its expression with a specific antisense oligonucleotide, partially, but significantly, decreased the cytotoxic activity of IL-2–stimulated NK cells. The inhibition of cytotoxic activity of IL-2–activated NK cells was not due to NO-mediated downmodulation of activation receptors (eg, CD25 and I-A), adhesion molecules (eg, leukocyte function antigen-1 [LFA-1]) or serine esterase expression. Indeed, the expression of these molecules, which increased (LFA-1 and serine esterase) or were induced (CD25 and I-A) in IL-2–treated cells when compared with untreated cells, was not significantly influenced by the presence of iNOS inhibitors (not shown). A recent study40 reported that human NK cells are induced to express iNOS after treatment with IL-12/tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), but the generated NO appears to downregulate stimulation of lytic potential induced by these cytokines rather than to play a role as cytotoxic effector molecule. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the experimental conditions related to NK stimulation and/or to species differences. Consistent with our findings, an impairment of NK killing in mice genetically lacking iNOS has recently been shown.17 The genetic deletion or the functional inactivation of iNOS in Leishmania major–infected mice causes an extensive parasite spreading and abolishes the NK cell cytotoxic function as determined in vitro against51Cr-labeled YAC-1 targets in a 4-hour chromium release assay.

The NO-dependent toxic events may involve both cytolysis or apoptosis of tumor target cell, as previously suggested.10-14,41 Our findings indicate that NO may play a role as one of the mediators of rat IL-2–activated NK cell-mediated DNA fragmentation and lysis of tumor cells, in accordance with previous evidence indicating the involvement of NO in these events induced by murine NK cells.42

The basis of NO-mediated cytotoxicity of IL-2–activated NK cells against tumor cells could be different (as a review, see Cifone et al41) and include the combination of NO with metal-containing moieties in key enzymes of the mitochondrial respiratory chain leading to the inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport, inhibition of aconitase activity affecting iron metabolism, and inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase, the rate-limiting step in DNA synthesis. NO can also damage DNA directly by deamination of purine and pyrimidine bases resulting in mutations and strand breaks. NO-mediated DNA damage has been shown to induce p53 expression that arrests cell cycle progression in G1 allowing for repair of damaged DNA or induces apoptotic cell death. In addition, NO-induced DNA damage activates the nuclear poly (adenosine diphosphate [ADP]-ribose) polymerase accompanied by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and adenosine triphosphate depletion leading to cell death by energy deprivation.

Other than an effector (cytotoxic) function, we provide evidence that NO can play a role also in the regulatory functions of NK cells, which are dependent on their ability to produce lymphokines, particularly IFN-γ.37-39 Indeed, the iNOS inhibition through AG or L-NMMA significantly reduced the IL-2–induced IFN-γ release, in accordance with previous evidence showing that iNOS expression in vivo is essential for the IFN-γ release by NK cells.17,18There is considerable evidence from in vitro experiments that iNOS-derived NO can modulate the cytokine response of several cell types. This might be due to its ability to activate and inactivate ion channels, G proteins, protein tyrosine kinases, Janus kinases, redox-sensitive kinases, and transcription factors (for review, see Lander,43 Duhé et al,44 and Bogdan45). Two recent studies highlight the possibility that NO assumes a similar regulatory function also in vivo. In a murine model of hemorrhagic shock, in the absence of iNOS, the activation of NK-kB and Stat3, as well as the expression of IL-6 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) was significantly reduced in the lung and liver.46 In the mouse model of cutaneous leishmaniosis, iNOS was previously identified as a critical antileishmanial mechanism, which was thought to start operating only when macrophages become activated by IFN-γ–secreting CD4+ T cells (for review, see Fang47). A recent study shows that the expression of iNOS is not restricted to the T-cell–dependent late phase of infection, but is also an important component of the innate response of the host, where it is focally induced by IFN-α/β within the first 24 hours of infection.17 In iNOS−/− mouse, there was a 30-fold reduction of the baseline expression of IL-12 p40 mRNA and an almost complete lack of the upregulation of IFN-γ in the Leishmania major-infected skin and/or lymph node. The effect of NO on IFN-γ production by IL-2–activated NK cells could not be related to its involvement in the cytotoxic functions of these cells. Indeed, recent reports indicate that different stimuli, which are not able alone to trigger natural cytotoxicity, induce IFN-γ production from NK cells48,49 (B. Perussia, personal communication, May 1998), thus suggesting that different signaling events are required to elicit distinct NK cell functions. Tay and Welsh50 reported that the antiviral effector mechanisms by which NK cells control murine cytomegalovirus infection in liver, which did not require NK cell contact with virus-modified target cells, are abrogated by in vivo administration of the NOS inhibitor, L-NMMA. The NO-dependent IFN-γ production may thus represent a relevant mechanism in the NK cell-mediated resistance against viruses. Furthermore, IFN-γ is the main responsible factor for the hematopoiesis-inhibiting activity exerted by some NK cell subsets (as a review, see Trinchieri37 and Murphy and Longo51). On the other hand, several studies are consistent with a role of NO in the regulation of hematopoiesis.52 53 Thus, the NO-mediated IFN-γ release by NK cells could also represent a potential mechanism underlying the NK-mediated inhibition of hematopoiesis.

Supported by grants from Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica e Tecnologica (MURST 60% and 40%), the Centro Nazionale delle Ricerche, the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, and Comunità Economica ed Europea Contract BIO4-CT95-0062.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to M. Grazia Cifone, PhD, Department of Experimental Medicine, Via Vetoio 10, Coppito 2, 67100 L’Aquila, Italy; e-mail: cifone@univaq.it.