Abstract

In the literature, a correlation has been suggested between the occurrence of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) type 2 infection. To further investigate a possible role for EBV type 2 infection in the development of AIDS-NHL, we developed a sensitive and type-specific nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay and analyzed EBV types directly on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in three subgroups of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infected individuals: 30 AIDS-NHL patients, 42 individuals progressing to AIDS without lymphoma (PROG), either developing opportunistic infections (AIDS-OI) or Kaposi’s sarcoma (AIDS-KS), and 18 long-term asymptomatic individuals (LTA). Furthermore, EBV type analysis was performed on PBMC samples obtained from AIDS-NHL patients in the course of HIV-1 infection. The results showed that: (1) direct analysis of PBMC is superior to analysis of B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCL) grown from the same PBMC samples; (2) in HIV-1 infected individuals, there is a high prevalence of EBV type 2 infection (50% in LTA, 62% in progressors, and 53% in AIDS-NHL) and superinfection with both type 1 and 2 (24% in LTA, 40% in progressors, and 47% in AIDS-NHL); (3) EBV type 2 (super)infection is not associated with an increased risk for development of AIDS-NHL; (4) type 2 infection can be found early in HIV-1 infection, and neither type 2 infection nor superinfection correlates with a failing immune system.

EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS (EBV) is a widespread human gamma herpes virus, which selectively infects two types of target cells, ie, squamous epithelial cells in the oropharynx and B lymphocytes.1 After primary infection, which usually occurs asymptomatically, the virus persists for life in a latent form in the B lymphocytes.2 Reactivation of these latently infected B lymphocytes is controlled by specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses.3 During immunodeficiency, reactivation of EBV-infection can lead to uncontrolled lymphoproliferation.4 In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1–infected individuals, the majority of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related diffuse large cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) is EBV-positive and is thought to arise because of loss of EBV-specific T-cell immunity.5-7

Two different EBV types are distinguished based on polymorphisms in the genes encoding the nuclear antigens EBNA-2,8,9 which is required for transformation of B lymphocytes, and EBNA-3A, -3B, and -3C.10 These different virus types have been classified as type 1 and 2 EBV and show distinct biological differences.8,11 These differences are reflected in the reduced transforming capacity of type 2 viruses.12

In healthy individuals, both virus strains can be found in epithelial cells in the oropharynx.13 Yet, it has been reported that only one strain is present in the peripheral blood.13,14Type 1 strains are more prevalent in Caucasian and Asian populations, whereas both types are common in Africa and New Guinea.9,11,15,16 However, in HIV-1–infected individuals, it has been shown that the peripheral blood B lymphocytes frequently harbor EBV type 2 and that a high percentage of the AIDS patients has a dual infection with type 1 and 2.17,18 A cross-sectional study in patients with AIDS-related NHL has shown an equal prevalence of type 1 and 2 in the tumors.19 It has been suggested that loss of EBV-specific T-cell immunity may predispose immunocompromised individuals to superinfection with other EBV strains.17

To study persistent EBV infection in normal and immunocompromised individuals, biological assays have been used that are based on the spontaneous outgrowth of EBV-transformed B lymphocytes.20,21 These EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (B-LCL) can be EBV-typed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification across the polymorphic region of EBNA-2 or EBNA-3A.10 Because type 2 strains have a reduced transforming capacity, these biological assays most likely underestimate type 2 prevalence.22 In addition, these assays are time-consuming and vary widely in sensitivity. Therefore, we developed a sensitive and EBV type-specific PCR assay that can be used directly on peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples without the need of prior culture. Using this assay, we have determined EBV types in HIV-1 seropositive individuals directly on PBMC and compared the results with conventional EBV-typing on spontaneously established B-LCL.

We have used the sensitive and type-specific PCR assay to investigate the role of type 2 EBV and superinfection in the development of AIDS-NHL. First, in a cross-sectional analysis, we investigated EBV-type prevalence in three groups of HIV-1–infected individuals: AIDS-NHL patients, progressors to AIDS without lymphoma, and long-term asymptomatic individuals. Second, in the longitudinal part of the study, EBV type analysis was performed on PBMC samples obtained from AIDS-NHL patients early and late in the course of HIV-1 infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

This study was performed on participants of the Amsterdam Cohort studies on AIDS and HIV-1 infection and HIV-1–infected individuals visiting the Academical Medical Center (AMC). Blood samples from these (homosexual) individuals at risk for HIV-1 infection were collected every 3 months for HIV-1 serology and immunologic studies. In addition, at all time points PBMC were cryopreserved. Individuals who were HIV-seronegative at entry of the cohort study and seroconverted during follow-up, were classified as seroconverters. Patients from the AMC and individuals who were already HIV-seropositive at entry in the cohort were classified as seroprevalent individuals.

We analyzed 30 patients with AIDS-related diffuse large cell NHL (median follow-up, 49 months). In comparison, 42 cohort participants who progressed to AIDS (classification of the Centers for Disease Control 1993) without a lymphoma (progressors, [PROG]) within 7 years after seroconversion (median seropositive follow-up, 54 months) were studied. Of these progressors, 29 developed an opportunistic infection (AIDS-OI), and 13 developed Kaposi’s sarcoma (AIDS-KS). Furthermore, 18 HIV-1 seropositive long-term asymptomatic individuals (LTA) with CD4+ T-cell counts above 500/μL during more than 8 years of seropositive follow-up (median follow-up, 148 months) were studied. Characteristics of the HIV-1–infected individuals are in part described elsewhere23 and are summarized in Table 1.

B-cell lines.

Spontaneous EBV-transformed B-LCL were established as previously described.7,24 25 Briefly, PBMC were thawed, resuspended in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) supplemented with L-glutamine, antibiotics, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Hyclone, UT) and cyclosporin A (CsA, final concentration 0.1 μg/mL; Sandoz, Basel, Switzerland) and cultured in limiting dilution at 6 serial dilutions with concentrations ranging from 0.5 × 106to 1.5 × 104 cells per well (6 replicate cultures per dilution) in a 96-well microtiter plate. Cells were fed weekly with RPMI/10% FCS supplemented in the first weeks with CsA. Wells that showed outgrowth of EBV-transformed B lymphocytes, as monitored microscopically, were expanded.

The B95.8 cell line and the Ag876 cell line were used as EBV type 1 and 2 positive controls, respectively. The EBV-negative B-cell line BJAB was used as a negative control.

Anti-CD3 proliferation assay.

T-lymphocyte reactivity to CD3 monoclonal antibody (CLB-T3/4E, CLB, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) was determined in a whole-blood lymphocyte culture assay and expressed as cpm per 103 CD3+T lymphocytes.26

DNA extraction.

Cells were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed by addition of L6-lysis buffer.27 After incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature, DNA was precipitated by addition of isopropanol, washed twice with 70% ethanol, and dissolved in dH2O. DNA concentration was measured by optical densimetry at 260 nm.

PCR for EBV typing on B-LCL and PBMC.

Genomic DNA extracted from B-LCL and PBMC (100 ng in case of DNA from B-LCL and control cell lines, 1 or 2 μg in case of DNA from PBMC) was amplified in 50-μL reactions containing 5.0 μL 10X PCR buffer (100 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 500 mmol/L KCl, and 0.01% wt/vol gelatin), 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L deoxy nucleoside triphosphate (dNTPs; Promega, Madison, WI; 2.5 mmol/L each), 1 U DNA Taq polymerase (Promega), and 100 ng of the EBNA-2 primers. For the amplification of EBNA-2–specific DNA extracted directly from PBMC, a nested PCR was performed using primers EBNA-2I and EBNA-2F in the first reaction. The region within the EBNA-2 gene discriminating between EBV type 1 and 2 was amplified with the nested primers EBNA-2C and EBNA-2G for type 1 and EBNA-2C and EBNA-2B (kindly provided by A.B. Rickinson, CRC Institute for Cancer Studies, University of Birmingham, Birmingham) for type 2. For the amplification of EBNA-2–specific DNA from B-LCL, a single PCR was performed using the nested primers only. For primer sequences, see Table 2.

For the first reaction of this nested PCR, denaturation was performed at 94°C for 1 minute, the primers annealed at 52°C for 90 seconds, and extension was performed at 72°C for 4 minutes. For the second reaction of the nested PCR, denaturation was performed at 94°C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 52°C for 1 minute, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes. The cycles were repeated 35 times followed by a final extension time of 10 minutes. The whole procedure was automated using a thermal cycler (Amersham [Roosendaal, The Netherlands] and Perkin Elmer [Foster City, CA]). After PCR, the identity of the amplified EBV fragment, 250 bp for EBV type 1 and 300 bp for EBV type 2, was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Southern blot analysis.

PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels and transferred to Genescreen plus (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA) membranes. Membranes were hybridized with either an EBNA-2 type 1-specific probe, EBNA-2.1, or an EBNA-2 type 2-specific probe, EBNA-2.2, labeled with γ32P-deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP). Sequences of both oligonucleotide probes (kindly provided by A.B. Rickinson) are depicted in Table 2.

Statistical analysis.

For statistical analysis, χ2 tests and the Kruskal-Wallis test were performed using the software program SPSS version 7.5 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Sensitivity and type-specificity of the nested PCR.

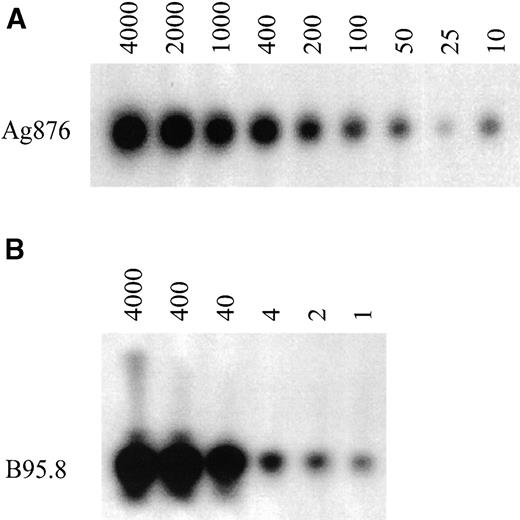

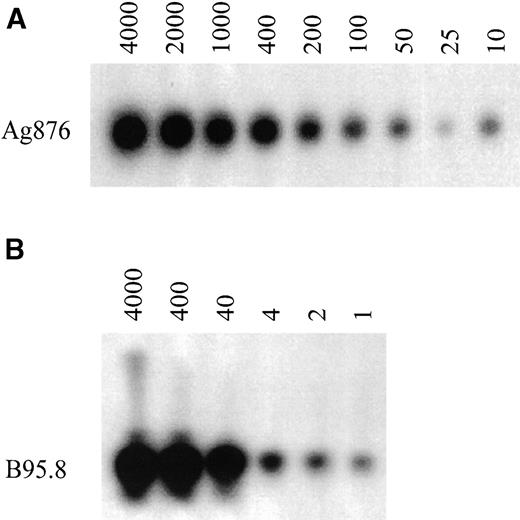

To analyze the EBV type directly on PBMC, a nested PCR assay was developed. Using the EBV type 1 and 2 positive cell lines, B95.8 and Ag876, the optimal conditions for the PCR assay were determined. Dilution of both cell lines in an EBV-negative background gave an estimation of the sensitivity. Type 2 DNA from the Ag876 cell line could still be detected at a dilution of 10 cells in a background of 2 × 105 EBV-negative cells (Fig 1A). Type 1 DNA from the B95.8 cell line, which contains more EBV copies per cell than the Ag876 cell line, could still be detected at a dilution of 1 cell in a background of 2 × 105 EBV-negative cells (Fig 1B). Similar data were obtained when diluting the B95.8 cell line in a type 2 background or diluting the Ag876 cell line in a type 1 background (data not shown). On all occasions, EBV type 1 DNA was not detected in the type 2 PCR and type 2 DNA was not detected in the type 1 PCR. Negative controls (EBV-negative B-cell lines, PBMC from an EBV-negative individual) were indeed always negative.

Sensitivity of the nested PCR for EBV-typing on PBMC. PCR analysis was performed on sequential dilutions of the EBV-positive cell lines, B95.8 and Ag876. (A) Dilution of Ag876 (number of cells) in a total of 2 × 105 EBV-negative background cells and (B) dilution of B95.8 (number of cells) in a total of 2 × 105EBV-negative background cells.

Sensitivity of the nested PCR for EBV-typing on PBMC. PCR analysis was performed on sequential dilutions of the EBV-positive cell lines, B95.8 and Ag876. (A) Dilution of Ag876 (number of cells) in a total of 2 × 105 EBV-negative background cells and (B) dilution of B95.8 (number of cells) in a total of 2 × 105EBV-negative background cells.

Comparative analysis of EBV types in B-LCL and PBMC.

A total of 76 B-LCL were grown from PBMC of nine HIV-1–infected individuals and typed by PCR amplification across the polymorphic locus of EBNA-2 using a single PCR assay. In parallel, PBMC samples obtained at the same time point from the same individuals were analyzed for the presence of EBV type 1 and 2 using the nested PCR assay.

EBV type analysis of B-LCL showed that 7 of 9 HIV-1–infected individuals harbored only type 1 EBV; 1 patient harbored only EBV type 2 and 1 showed dual infection with both types (Table 3). In contrast, EBV type analysis performed on PBMC showed that only 4 of these HIV-1–infected subjects harbored only EBV type 1. The other 5 individuals harbored both type 1 and type 2.

Analysis of B-LCL would have suggested that only 2 of 9 individuals had a type 2 infection, whereas direct EBV-typing of PBMC showed that 5 of 9 individuals were infected with EBV type 2. Interestingly, in the dually infected AIDS-NHL patient N319, the type 1 strain detected in PBMC could not be shown by analyzing EBV types in B-LCL. Thus, using B-LCL not only the EBV type 2 prevalence would have been underestimated, but also the prevalence of superinfection.

EBV type 2 infection and superinfection in different groups of HIV-infected individuals.

Using the sensitive and type-specific nested PCR, EBV-typing was performed on PBMC from different groups of HIV-1–infected individuals: patients with AIDS-NHL (n = 30), progressors to AIDS (OI/KS, n = 42), and LTA (n = 18). From the LTA, the PBMC samples analyzed had been obtained in the ninth year of follow-up when CD4+ T-cell counts of 10 individuals were still above 500/μL. In case of progressors and AIDS-NHL patients, PBMC samples were analyzed either at AIDS-OI/KS diagnosis or AIDS-NHL diagnosis, respectively, or in the year preceding diagnosis.

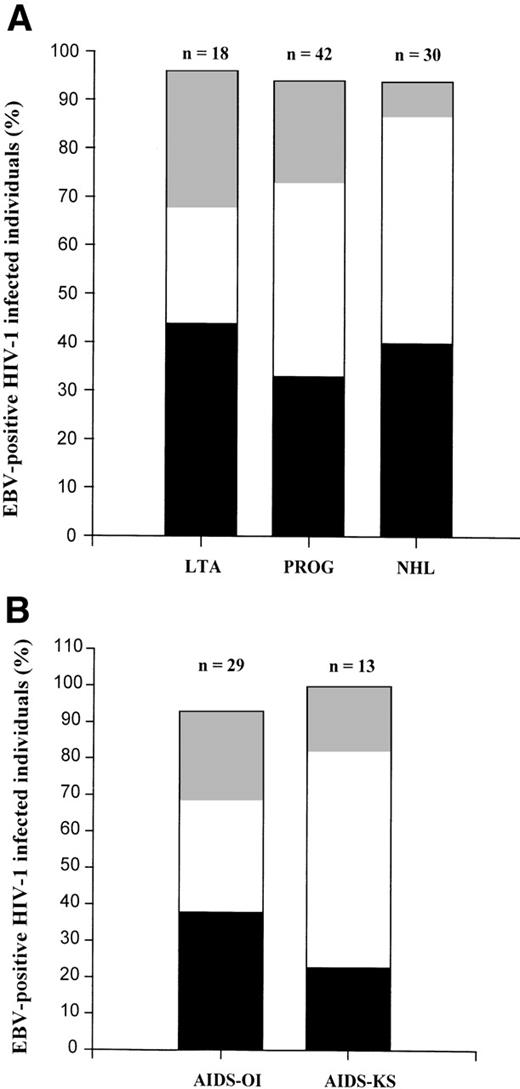

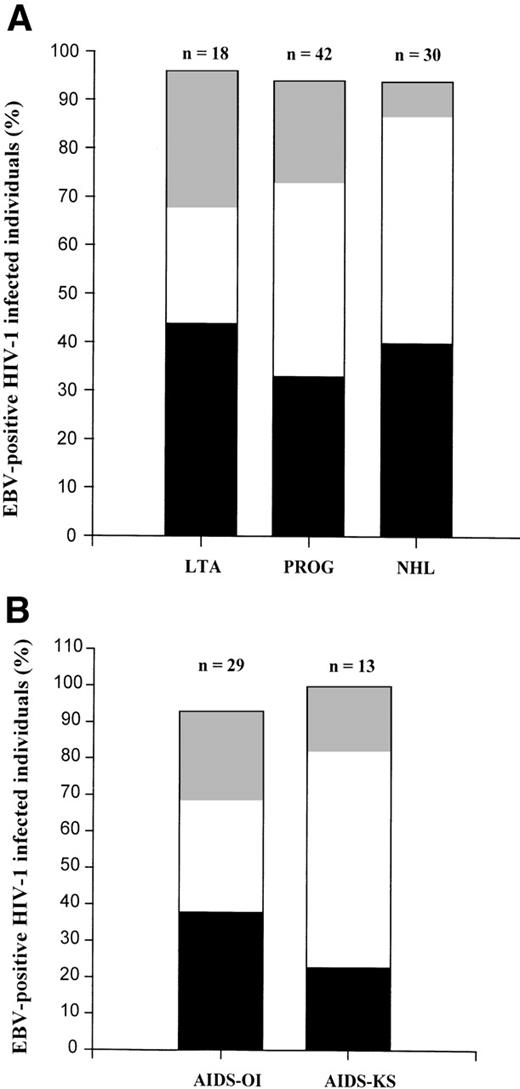

A total of 90 HIV-1–infected individuals was studied. Patient characteristics of all groups are summarized in Table 1. In 6% of the individuals, no EBV could be detected. As shown in Fig 2A, only EBV type 1 was found in 44% of the LTA, 33% of the progressors, and 40% of the AIDS-NHL patients. Only EBV type 2 infection was found in 28% of the LTA, 21% of the progressors, and in 7% of AIDS-NHL patients. The total percentage of type 2 infected individuals, which includes superinfected individuals, was comparable between the three groups (50% in LTA, 62% in progressors, and 53% in AIDS-NHL). However, the percentage of superinfected individuals was significantly higher both in AIDS-NHL (47%) and progressors (40%) when compared with LTA (24%, P< .005, χ2). There was no difference in superinfection between the total group of progressors and AIDS-NHL patients. Interestingly, when the progressors to AIDS were subdivided into separate groups: AIDS-OI (n = 29) and AIDS-KS (n = 13), the percentage of superinfected individuals was significantly higher in AIDS-KS, as compared with AIDS-OI (P = .017, χ2, see Fig 2B). The percentage of superinfected individuals was similar in AIDS-OI and LTA, whereas in both AIDS-KS and AIDS-NHL, the percentage of superinfected individuals was significantly higher than in LTA (P < .001).

EBV types in subgroups of HIV-1–infected individuals. (A) Contribution of EBV type 1 (▪), EBV type 2 (▩), and dual infection (□) in the total percentage of EBV-positive individuals in different groups of HIV-1–infected subjects (LTA, PROG, and NHL). EBV-type assessment was performed by type-specific PCR analysis directly on PBMC as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Contribution of EBV type 1 (▪), EBV type 2 (▩), and dual infection (□) in the total percentage of EBV-positive individuals in two groups of progressors to AIDS (AIDS-OI and AIDS-KS). EBV-type assessment was performed by type-specific PCR analysis directly on PBMC as described in Materials and Methods.

EBV types in subgroups of HIV-1–infected individuals. (A) Contribution of EBV type 1 (▪), EBV type 2 (▩), and dual infection (□) in the total percentage of EBV-positive individuals in different groups of HIV-1–infected subjects (LTA, PROG, and NHL). EBV-type assessment was performed by type-specific PCR analysis directly on PBMC as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Contribution of EBV type 1 (▪), EBV type 2 (▩), and dual infection (□) in the total percentage of EBV-positive individuals in two groups of progressors to AIDS (AIDS-OI and AIDS-KS). EBV-type assessment was performed by type-specific PCR analysis directly on PBMC as described in Materials and Methods.

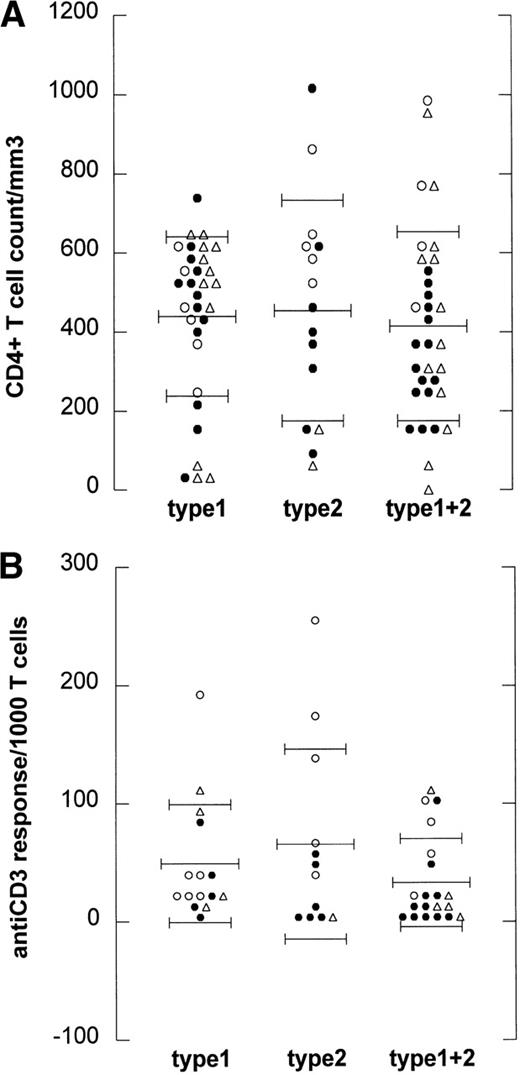

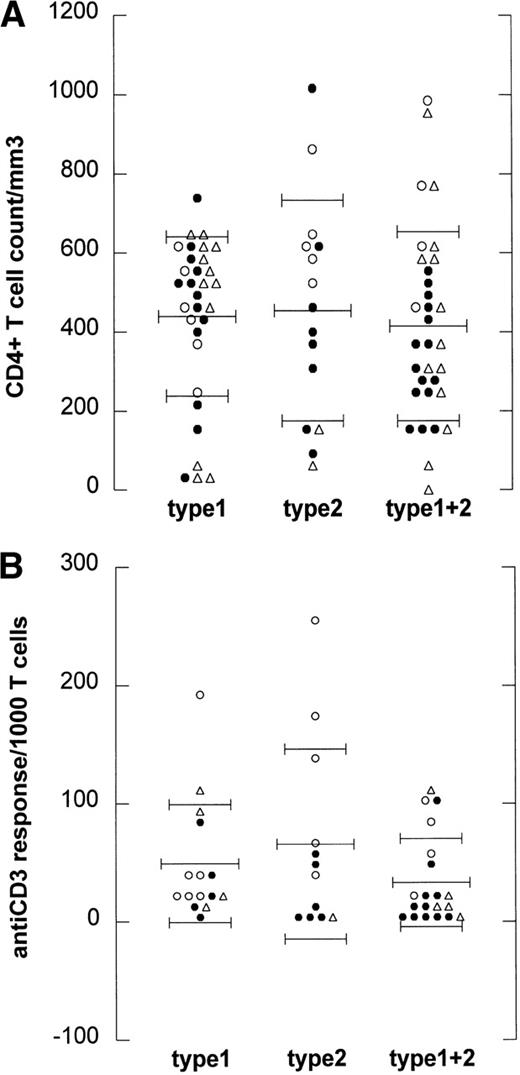

To analyze whether the occurrence of type 2 infection or superinfection is related to the degree of immunodeficiency of the HIV-1–infected individuals, we studied both CD4+ T-cell counts and T-cell function.28 29 CD4+ T-cell counts for LTA were higher than for progressors to AIDS (OI/KS and NHL, P= .015, Kruskal-Wallis test). When CD4+ T-cell counts at the time point of EBV typing were plotted against the EBV strain(s) that was (were) detected, there was no statistically significant difference between CD4+ T-cell counts of type 1 (mean, 0.44 ± 0.21), type 2 (mean, 0.45 ± 0.24), and superinfected individuals (mean, 0.41 ± 0.16), as shown in Fig 3A.

EBV type infection in relation to immune status. (A) CD4 counts are depicted for every HIV-1–infected individual harboring EBV type 1 (type 1), EBV type 2 (type 2), or harboring both type 1 and 2 (type 1+2). Mean CD4 count per group is depicted by the long thin lines, standard deviation by the short thin lines. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups (Kruskal-Wallis). (B) Anti-CD3 responses expressed as cpm/1,000 T cells are depicted for 48 HIV-1–infected individuals harboring EBV type 1 (type 1), EBV type 2 (type 2), or harboring both type 1 and 2 (type 1+2). Mean anti-CD3 response per group is depicted by the long thin lines, standard deviation by the short thin lines. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups (Kruskal-Wallis). (○), LTA; (•), progressors; (▵), NHL.

EBV type infection in relation to immune status. (A) CD4 counts are depicted for every HIV-1–infected individual harboring EBV type 1 (type 1), EBV type 2 (type 2), or harboring both type 1 and 2 (type 1+2). Mean CD4 count per group is depicted by the long thin lines, standard deviation by the short thin lines. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups (Kruskal-Wallis). (B) Anti-CD3 responses expressed as cpm/1,000 T cells are depicted for 48 HIV-1–infected individuals harboring EBV type 1 (type 1), EBV type 2 (type 2), or harboring both type 1 and 2 (type 1+2). Mean anti-CD3 response per group is depicted by the long thin lines, standard deviation by the short thin lines. No statistically significant difference was found between the groups (Kruskal-Wallis). (○), LTA; (•), progressors; (▵), NHL.

Because the T-cell response to mitogens may be a more sensitive marker for HIV-1–induced immune dysfunction than CD4+ T-cell counts,28 29 the anti-CD3 response was studied in vitro from 47 of the 90 individuals at the time point of EBV typing. In Fig3B, the anti-CD3 responses (expressed as cpm per 1,000 T lymphocytes) at the time point of EBV-typing were plotted against the EBV strain(s) that was (were) detected. No difference was found between the anti-CD3 response of type 1 (mean, 49 ± 33), type 2 (mean, 66 ± 49), and superinfected individuals (mean, 33 ± 24).

EBV superinfection in the course of HIV-1 infection.

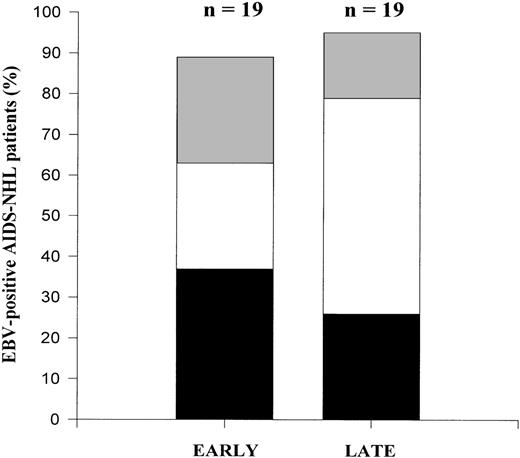

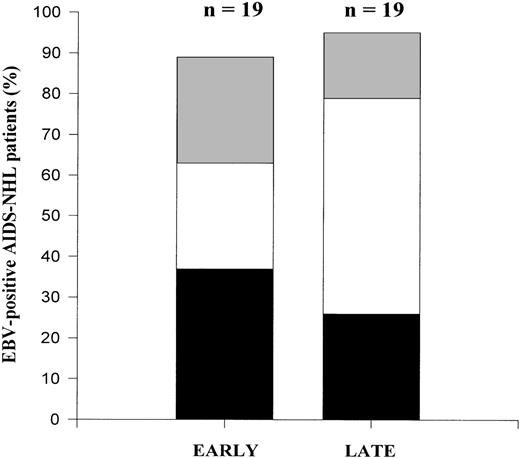

From 19 individuals who developed AIDS-NHL, PBMC samples obtained from early and late time points in the course of HIV-1 infection were studied to investigate a possible role of type 2 (super)infection in the development of AIDS-NHL. In case of the seroconverter, PBMC samples were studied at HIV seroconversion (early) and at AIDS-NHL diagnosis (late). In case of seroprevalent individuals, PBMC samples obtained either at entry in the Amsterdam Cohort Studies or at the first hospital visit (early) and at AIDS-NHL diagnosis (late) were studied.

EBV typing using the nested PCR assay showed that a considerable proportion of the individuals studied (50%) were infected with type 2 EBV already early in HIV-1 infection (Fig4). Moreover, half of the type 2 infected subjects had a superinfection already early. The percentage of AIDS-NHL patients that were superinfected early was comparable to the percentage of superinfected LTA individuals. In the course of time, there was a statistically significant increase in superinfection (P = .009), with either type 1 or type 2, depending on the strain present initially: 3 patients harbored a type 2 strain early in HIV-1 infection and were superinfected with a type 1 strain late in HIV-1 infection; 2 patients harbored a type 1 strain at an early time point and were superinfected with a type 2 strain at a late time point in HIV-1 infection. No loss of EBV strains was observed. Thus, superinfection in the course of HIV-1 infection does occur, but can involve both type 1 and type 2.

Longitudinal analysis of EBV types in AIDS-NHL patients. Contribution of EBV type 1 (▪), EBV type 2 (▩), and dual infection (□) in the total percentage of EBV-positive AIDS-NHL patients in early and late PBMC samples in the course of HIV-1 infection. EBV type discrimination was performed by type-specific PCR analysis on PBMC as described in Materials and Methods.

Longitudinal analysis of EBV types in AIDS-NHL patients. Contribution of EBV type 1 (▪), EBV type 2 (▩), and dual infection (□) in the total percentage of EBV-positive AIDS-NHL patients in early and late PBMC samples in the course of HIV-1 infection. EBV type discrimination was performed by type-specific PCR analysis on PBMC as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have used a sensitive and type-specific nested PCR to analyze EBV types in subgroups of HIV-1–infected individuals. We have reached the following conclusions: (1) direct analysis of PBMC may be superior to analysis of B-LCL grown from the same PBMC samples; (2) in HIV-1–infected individuals, there is a high prevalence of EBV type 2 infection and superinfection with both type 1 and 2; (3) there is no evidence for an association between EBV type 2 infection or superinfection and an increased risk for development of AIDS-NHL; and (4) EBV type 2 infection or acquisition of superinfection is not merely a reflection of a failing immune system in HIV-1–infected individuals.

The EBV type 2 and superinfection prevalence found in the present study is higher than reported in studies analyzing EBV-types on B-LCL.17,18,30 The underestimation of EBV type 2 found by analysis of B-LCL is probably due to culture bias because the transforming capacity of type 2 strains is reduced. This finding stresses the importance of using direct PCR assays for EBV detection in clinical samples. This issue has also recently been addressed by Haque et al.31 Furthermore, if we would have studied B-LCL only, we would have found a possible correlation between EBV type 2 infection and AIDS-NHL because the two type 2–infected individuals identified in that assay were both AIDS-NHL patients (see Table 3). This would have been in agreement with the literature.6 In contrast, EBV-type analysis on PBMC of these same patients showed that 3 of the 5 type 2–infected individuals were AIDS-NHL patients and 2 were AIDS-OI patients, a result not suggestive of a correlation between EBV type 2 infection and the development of AIDS-NHL. Therefore, studies performed on B-LCL, which suggest an association between EBV type 2 and the development of lymphoma, may be of limited value.

Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the possible pathogenic role of EBV type 2 infection and superinfection by comparing three large subgroups of HIV-1–infected individuals by direct EBV type analysis on PBMC: AIDS-NHL patients, progressors to AIDS-OI/KS, and LTA individuals. By studying these groups, no relation could be found between either type 2 infection or superinfection and the development of AIDS-NHL.

In the longitudinal study, five AIDS-NHL patients showed acquisition of superinfection, either with type 1 or 2. If this finding would be viewed separately, it might be tempting to conclude that superinfection is the result of immunodeficiency. However, considering the other data obtained in this study, it is clear that immunodeficiency at most contributes to, but does not cause the superinfection. The conclusion that immunodeficiency does not cause superinfection is based on the fact that (1) no difference could be found in mean CD4+T-cell counts and mean T-cell response in vitro between EBV type 1 carriers, EBV type 2 carriers, and superinfected individuals; (2) LTA individuals, who were asymptomatic for more than 8 years with CD4+ T-cell counts higher than 500 per μL, already showed high prevalence of type 2 infection and superinfection; (3) analysis of EBV-types at early and late time points in the course of HIV-1 infection showed that the majority of the patients already harbor EBV type 2 early in HIV-1 infection, with some of them already showing superinfection; and (4) we found high EBV type 2 and superinfection prevalence in AIDS-KS patients, who develop KS when CD4+T-cell counts are still high (median CD4+ T-cell counts = 520/μL).32

Most likely the high type 2 prevalence found (early) in HIV-1 infection indicates a higher type 2 prevalence in homosexual populations, offering a new view on the epidemiology of EBV infection. This would be in agreement with Yao et al,33 who recently suggested a higher type 2 prevalence in homosexual populations based on the comparison of EBV-type infection in B-LCL from HIV-infected homosexuals (31% total type 2 infection) and HIV-infected (heterosexual) hemophiliacs (10% total type 2 infection). Moreover, the finding that EBV-type 2 prevalence is very high in AIDS-KS patients also suggests that these infections are related to sexual behavior because KS is believed to be caused by human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), which has been shown to be sexually transmitted.34

Until now, B-LCL-analysis has shown that 1% to 3% of healthy Caucasian EBV carriers in Europe harbor a type 2 strain. Our data suggest that type 2 infections are much more prevalent, especially among homosexual men. To elucidate EBV epidemiology in western Europe, it is necessary to perform a detailed study of EBV strains in HIV-negative homosexual and heterosexual populations using direct PCR analysis of PBMC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was part of the Amsterdam Cohort Studies on AIDS and HIV-1 infection, a collaboration of the Municipal Health Service, the Academical Medical Center, and the CLB. We thank Dr M. Roos and collaborators for immunological data.

Supported by Grant No. 96-1168 from the Dutch Cancer Society and Grant No. 1007 from the Dutch AIDS Fund.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Debbie van Baarle, MSc, Department of Clinical Viro-Immunology, CLB, Sanquin Blood Supply Foundation, Plesmanlaan 125, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: D_van_Baarle@clb.nl.