Abstract

This work was aimed at elucidating the molecular genetic lesion(s) responsible for the thrombasthenic phenotype of a patient whose low platelet content of glycoprotein (GP) IIb-IIIa indicated that it was a case of type II Glanzmann’s thrombasthenia (GT). The parents did not admit consanguinity and showed a reduced platelet content of GPIIb-IIIa. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–single-stranded conformational polymorphism analysis of genomic DNA showed no mutations in the patient’s GPIIIa and two novel mutations in the GPIIb gene: one of them was a heterozygous splice junction mutation, a C→A transversion, at position +2 of the exon 5-intron 5 boundary [IVS5(+2)C→A] inherited from the father. The predicted effect of this mutation, insertion of intron 5 (76 bp) into the GPIIb-mRNA, was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR analysis of platelet mRNA. The almost complete absence of this mutated form of GPIIb-mRNA suggests that it is very unstable. Virtually all of the proband’s GPIIb-mRNA was accounted for by the allele inherited from the mother showing a T2113→C transition that changes Cys674→Arg674 disrupting the 674-687 intramolecular disulfide bridge. The proband showed a platelet accumulation of proGPIIb and minute amounts of GPIIb and GPIIIa. Moreover, transfection and immunoprecipitation analysis demonstrated that [Arg674]GPIIb is capable of forming a heterodimer complex with GPIIIa, but the rate of subunit maturation and the surface exposure of GPIIb-IIIa are strongly reduced. Thus, the intramolecular 674-687 disulfide bridge in GPIIb is essential for the normal processing of GPIIb-IIIa complexes. The additive effect of these two GPIIb mutations provides the molecular basis for the thrombasthenic phenotype of the proband.

GLANZMANN reported a case of a bleeding disorder, starting immediately after birth, characterized by prolonged bleeding time and abnormal clot retraction.1 Based on these features, he named this disease “thrombasthenia.” The platelets from these patients would not spread or aggregate, indicating that they were defective.2,3 The finding that the fibrinogen content in platelets was low or absent2,4,5 led to the conclusion that the fibrinogen receptor was either defective or deficient in thrombasthenic phenotypes.6,7 The fibrinogen receptor, expressed only in platelets, is a noncovalent, calcium-dependent, heterodimeric complex, formed by glycoprotein (GP) IIb and GPIIIa, that belongs to the superfamily of cell surface adhesive receptors termed integrins8 and so is also referred to as integrin αIIbβ3. This receptor binds adhesive proteins other than fibrinogen, such as von Willebrand factor, vitronectin, and fibronectin.9 10

Caen11 classified Glanzmann thrombasthenia (GT) into types I or II based on their platelet fibrinogen content and clot-retracting capability: type I GT platelets lack fibrinogen and clot retraction; in type II GT, platelets showed low to moderate clot retraction capability and detectable amounts of fibrinogen. In agreement with these observations, GPIIb-IIIa was found to be absent in the platelet membrane of type I GT and present at only 10% to 20% of the control values in type II GT. Another type of GT, termed variants, representing less than 10% of the total number of cases, has also been identified in which platelets possess normal or near normal (60% to 100%) expression of dysfunctional receptors.7 12

From a molecular biological point of view, GT is a heterogeneous disease.13 As the cDNA and the structural organization of the GPIIb and GPIIIa genes became available,14-18 it was possible to establish that the molecular basis for this heterogeneity is the result of distinct genetic lesions in the GPIIb and GPIIIa genes. Since then, point mutations leading to single amino acid substitutions, insertions or deletions, nonsense mutations, or splicing abnormalities have been reported in both genes.19 The majority of these lesions are associated with type I GT.

The present work reports the studies on a patient of type II GT resulting from compound heterozygosity for the GPIIb gene, who inherited a mutation in the splicing junction of the exon 5-intron 5 boundary of GPIIb [IVS5(+2)C→A] from her father and a T2113→C transition that changes Cys674to Arg from her mother. Functional studies of these two mutations demonstrated their association with the thrombasthenic phenotype of the patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analysis of GPIIb-IIIa and fibrinogen content.

Platelet content of GPIIb, GPIIIa, and fibrinogen was determined by competitive enzyme immunoassays, using monoclonal anti-GPIIb (M3), anti-GPIIIa (P37), and antifibrinogen (F2) antibodies20 21 and pure GPIIb, GPIIIa, and fibrinogen as standards.

For Western blot analysis of the GPIIb-IIIa content, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-solubilized platelet proteins were first separated on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing and nonreducing conditions, electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and then incubated with anti-GPIIIa (P37) and anti-GPIIb (M3) specific antibodies. The immunoreactive bands were digitized with a high resolution scanner and analyzed on a Macintosh (Cupertino, CA) computer using the public domain NIH Image program (developed at the US National Institutes of Health and available on the Internet at http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image/).

Flow cytometry.

Platelets or stably transfected CHO cells were harvested using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mmol/L or 0.5 mmol/L EDTA, respectively, incubated with a monoclonal antibody (MoAb) directed against either GPIIb (M3) or GPIIIa (P37) and then exposed to fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated (FITC) F(ab′)2fragment of rabbit antimouse Ig (Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) and the surface fluorescence was analyzed in a Coulter flow cytometer (model EPICS XL; Coulter, Hialeah, FL).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of GPIIb- and GPIIIa-mRNA from platelet and stably transfected CHO cells.

Platelet total RNA was prepared by the guanidinium thiocyanate method,22 reverse-transcribed with the primer GPIIb-(1275-1255) 5′-ACCCAGGAACACCAGCACTTG-3′, and used as template for the amplification of a 779-bp fragment encompassing exons 5 to 13 of GPIIb with the following oligonucleotides: sense, GPIIb-(497-517) 5′-CAGAGAGCGGCCGCCGCGCCG-3′, and antisense, GPIIb-(1275-1255). To search for mutant forms of GPIIb-mRNA with insertion of intron 5, a sense primer specific for sequences of intron 5, GPIIb-(intron 5, 1-19) 5′-GCGAGTAGGGAGCAAAAGC-3′, and the antisense primer GPIIb-(497-517) were used. Hybridization analysis of the PCR products was performed as previously described23using as probes GPIIb DNA fragments lacking the oligonucleotide sequences used for amplification.

Total RNA from the proband and her parents was also reverse-transcribed with the primer GPIIb-(3154-3133), 5′-CAACCCTCCTGCTAGAATAGTG-3′, and used as template for the PCR amplification of a 1,190-bp fragment encompassing exons 20 to 30 of GPIIb with the oligonucleotides: sense, GPIIb-(1965-1985) 5′-AGTTGGGGCAGATAATGTCCT-3′; and antisense, GPIIb-(3154-3133).

Total RNA from CHO cells stably transfected with GPIIIa and either normal or mutant [IVS5(+2)C→A]GPIIb was extracted as described above and reverse-transcribed using the antisense oligonucleotide GPIIb-(1513-1489) 5′-CACAGCTCTTCACAGCAGGATTCAG-3′. A 479-bp fragment of normal GPIIb-cDNA was amplified using the oligonucleotides: sense, GPIIb-(497-517) 5′-CAGAGAGCGGCCGCCGCGCCG-3′, and antisense, GPIIb-(975-956) 5′-AGCCACTGAATGCCCAAAAT-3′. The predicted size of the amplified fragment with insertion of intron 5 is 555 bp.

PCR-based quantitation of platelet GPIIb- and GPIIIa-mRNA with the TaqMan system.

The instrumentation and the fluorogenic probes of the Perkin-Elmer Cetus (Norwalk, CT) LS-50B TaqMan System were used for PCR-based quantitation of GPIIb and GPIIIa mRNA in platelets from the proband, her parents and sister, and normal individuals, as previously described.24 Specific oligonucleotide probes, R-CTCTGGCGCGTTCTTCCTCAAATTTAGC-Q, R-AGTGACCACGGAGCTGAAGCCCG-Q, and R-ATGCCCT-Q-CCCCCATGCCATCCTGCGT, were designed to anneal to targets located within PCR-amplified fragments of 132 bp (2157-2288) of GPIIIa, 194 bp (582-776) of GPIIb, or 295 bp (2141-2435) of β-actin cDNA, respectively. The location of the reporter and quencher dyes are indicated by R and Q, respectively. We first assessed the range of both the number of PCR cycles and the amounts of template that would yield a linear response between DNA target doses and fluorescence signal from amplified products. Different dilutions of RNA samples were used for amplification of GPIIIa, GPIIb, and β-actin DNA fragments using the rTth polymerase XL from Perkin-Elmer Cetus. Briefly, in a first-step mRNA was reverse-transcribed with the antisense primers in the presence of 1.1 mmol/L Mn(OAc)2 during 30 minutes at 60°C. Then, the PCR amplification was performed by chelating the Mn2+ and adding 0.8 mmol/L Mg(OAc)2, the sense primer, and the specific TaqMan probe. Twenty-five or 30 amplification cycles were performed consisting of 15 seconds at 95°C and 15 seconds at 65°C. After PCR cycling, 40 μL portions were taken from each sample and the fluorescence was measured using a 488 nm excitation wavelength and 518 and 580 nm emission wavelengths for the reporter and quencher dyes, respectively. Values were corrected for internal quenching and expressed as GPIIIa/β-actin and GPIIb/β-actin fluorescence ratios.

Single-stranded conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, cloning, and sequencing of PCR-amplified genomic DNA fragments.

PCR amplification of DNA fragments encompassing one or more exons of GPIIb or GPIIIa was performed as previously described.25Screening for mutations in GPIIb and GPIIIa was performed by “cold” SSCP analysis.26,27 A 442-bp DNA fragment encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb was amplified with the oligonucleotides: sense, 5′-GGCTGACCCCTCCTCCTTGT-3′, and antisense, 5′-CTGGAAGTCTGGAATGGCGGT-3′. Portions of the PCR product were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified, digested with Apa I to yield fragments of 321 and 121 bp, and used for SSCP analysis. A 193-bp DNA fragment encompassing exon 21 of GPIIb was amplified with the oligonucleotides: sense, 5′-TATATGATGCTCTGTAATTTC-3′, and antisense, 5′-TCTGGTTATTCATGAGCCCCT-3′. DNA products showing altered electrophoretic mobility patterns of single-stranded bands were cloned into a T vector28 and their primary nucleotide sequence was determined. DNA sequence analysis was performed as described by Marck.29

Construction of mammalian expression vectors with normal or mutant GPIIb cDNAs.

A GPIIb cDNA with intron 5 inserted, [intron 5]GPIIb, was prepared by the splicing by overlap extension (SOE) PCR procedure.30First, genomic DNA from the patient was used as template for PCR amplification of a fragment comprising exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb. This product was digested to generate a 93-bp Alu I/Hpa II fragment and a 54-bp Ban II fragment that overlap at the intron 5 region. Second, normal GPIIb-cDNA was used as template to generate two PCR overlapping fragments, hereafter referred to as 5′ and 3′ segments: the 5′ segment was amplified using the oligonucleotide GPIIb-(497-517) 5′-CAGAGAGCGGCCGCCGCGCCG-3′ as sense primer and the Alu I/Hpa II genomic fragment as antisense primer; the 3′ segment was obtained using theBan II digestion product as sense primer and the oligonucleotide GPIIb-(975-956) 5′-AGCCACTGAATGCCCAAAAT-3′ as antisense primer. Third, the 5′ and 3′ PCR products were used as template in a new round of PCR amplification with the oligonucleotides Not I andBsm I described above; the amplified DNA comprising intron 5 was digested with Not I and Bsm I, and the digestion product cloned in a vector containing the normal GPIIb cDNA previously digested with the same restriction enzymes. Normal or mutated [intron 5]-GPIIb-cDNA were subcloned into the HindIII site of pCEP4 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) to yield the plasmids pCEP4-GPIIb and pCEP4-[intron 5]GPIIb, respectively.

GPIIb cDNA with a T to C substitution at position 2113 was prepared by SOE PCR as described using two sets of oligonucleotide primers: GPIIb-sense-(955-979) 5′-TATTTTGGGCATTCAGTGGCTGTCA-3′, GPIIb-antisense-(2123-2103) 5′-TTCTGATTACGGATGAGTCTC-3′; and GPIIb-sense-(2103-2123) 5′-GAGACTCATCCGTAATCAGAA-3′, GPIIb-antisense-(3154-3133) 5′-CAACCCTCCTGCTAGAATAGT-3′. Bases substituted to generate a mutation in overlapping fragments are underlined. The final PCR product carrying the mutation was digested with Bsm I and Nae I and ligated in a vector containing the wild-type GPIIb cDNA previously digested with the same enzymes. Wild-type and mutated cDNA were subcloned into the HindIII site of pcDNA3 (Invitrogene).

Cell culture and transfection.

CHO cells stably expressing GPIIIa (CHO-GPIIIa cells)31 were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were transfected with 5 μg of either plasmid pCEP4-GPIIb or pCEP4-[intron 5]GPIIb using the calcium phosphate precipitation procedure.23 The transfected cells were fed with medium containing 200 μmol/L hygromycin every 3 to 4 days.

Transient transfection analysis of pcDNA3-GPIIIa and either pcDNA3-GPIIb or pcDNA3-(2113C)GPIIb into CHO cells was performed by the diethyl aminoethyl (DEAE)-dextran method.32

Selective cloning of exons by the Exontrap vector system.

Exontrap (Mo Bi Tec, Göttingen, Germany) is a vector system designed to selectively clone exon sequences from large genomic fragments.33 A 442-bp DNA fragment encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb was amplified with the primers for the intronic flanking regions (sense, 5′-GGCTGACCCCTCCTCCTTGT-3′, and antisense, 5′-CTGGAAGTCTGGAATGGCGGT-3′) using as template genomic DNA from the proband or a control. The resulting PCR products were blunt-end ligated into the Sma I site of the pET01, and selected clones carrying DNA from either the normal or the mutant alleles were transiently transfected into CHO cells. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the transfected cells was performed with primers for the exons of the pET01 vector: sense, 5′-GAGGGAATCCGCTTCCTGCCCC-3′, and antisense, 5′-CCGTGACCTCCACCGGGCCCTC-3′. The PCR products were cloned in a T vector and their DNA sequence was determined in both directions.

Labeling and immunoprecipitation analysis of GPIIb-IIIa complexes from platelets and CHO cells cotransfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or mutant forms of GPIIb.

To analyze surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa complexes, CHO cells were transfected with normal GPIIIa and either normal or (C2113)-GPIIb cDNA and, 72 hours after transfection, were washed twice with PBS, incubated in 2 mL of PBS containing 2.5 mmol/L biotin-NHS (D-biotin-N-hydroxysuccinimidester; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for 30 minutes followed by immunoprecipitation of GPIIb-IIIa complexes with the specific anti-GPIIIa (P37) or anti-GPIIb (M3) MoAb.21 The immunoprecipitates were processed as previously described.34

Total (surface and intracellular) GPIIb-IIIa complexes were detected by incubation of detergent lysates of platelets or transiently transfected CHO cells with biotin-NHS, followed by immunoprecipitation with specific MoAbs.34

Materials.

Restriction enzymes and hygromycin were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim, and DNA sequencing reagents were from Pharmacia Biotech (Uppsala, Sweden). The pCEP4 and pcDNA3 expression vectors were from Invitrogen, and the Exontrap vector system was purchased from Mo Bi Tec. Most other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO) or from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). [35S]-dATP (specific activity, 1,000 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham Ibérica (Madrid, Spain).

RESULTS

Case report.

The patient is an 11-year-old girl clinically diagnosed with GT whose history of bleeding episodes and unprovoked bruising started immediately after birth. Her parents, who are clinically asymptomatic, are not aware of any consanguinity or bleeding disorders in their relatives. Clinical hematological studies showed a bleeding time ≥15 minutes, a platelet count of 286,000/μL, and a clotting time of 7 minutes with very low clot retraction capability. Platelets failed to aggregate either spontaneously or in response to adenosine diphosphate (ADP), epinephrine, or collagen, but showed a normal response to ristocetin. Platelet adhesion to glass was 9%. The parents of the proband showed decreased platelet aggregation in response to ADP or epinephrine but normal responses to collagen or ristocetin.

Platelet GPIIb-IIIa content.

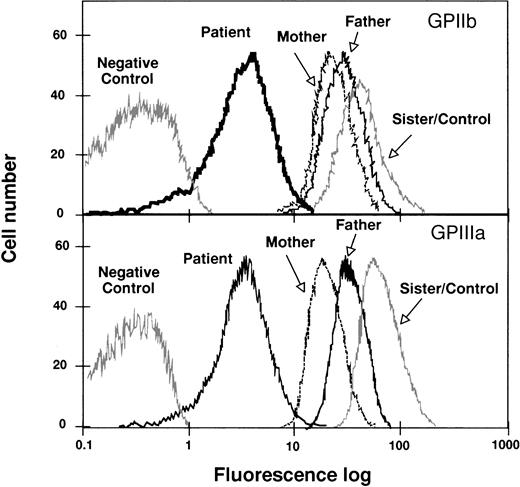

The surface level of platelet GPIIb-IIIa was analyzed by flow cytometry, using anti-GPIIb or anti-GPIIIa MoAbs. The histograms in Fig 1 show representative tracings of fluorescence intensities of platelets from the proband and family members. The proband showed GPIIb and GPIIIa mean fluorescence intensities minus the background of about 10% of the control values. Both parents showed a marked decrease in the mean fluorescence intensity of both GPIIb and GPIIIa, whereas the platelets from the sister of the proband showed values similar to those of the control platelets. Enzyme immunoassay and immunoblotting analysis confirmed the results obtained by flow cytometry (Table1). The proband’s platelet fibrinogen content is 25% of the control, which is greater than the reported values for patients with GT showing no surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa.35

Flow cytometric analysis of GPIIb-IIIa content in platelets from the proband, her father, mother, and sister. Washed platelets were incubated with anti-GPIIIa or anti-GPIIb MoAbs as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as semilog plots of cell number versus fluorescence intensity. The upper panel shows the surface expression of GPIIb, using the MoAb M3, in platelets from the patient, from her parents and sister, and from a normal unrelated individual. The lower panel represents the surface expression of GPIIIa using the MoAb P37. The negative control represents the fluorescent signal of platelets treated only with the second antibody. The plot corresponding to the sister’s platelets overlaps with the control and, therefore, only one tracing was represented. For the sake of clarity, the original plots have been redrawn.

Flow cytometric analysis of GPIIb-IIIa content in platelets from the proband, her father, mother, and sister. Washed platelets were incubated with anti-GPIIIa or anti-GPIIb MoAbs as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as semilog plots of cell number versus fluorescence intensity. The upper panel shows the surface expression of GPIIb, using the MoAb M3, in platelets from the patient, from her parents and sister, and from a normal unrelated individual. The lower panel represents the surface expression of GPIIIa using the MoAb P37. The negative control represents the fluorescent signal of platelets treated only with the second antibody. The plot corresponding to the sister’s platelets overlaps with the control and, therefore, only one tracing was represented. For the sake of clarity, the original plots have been redrawn.

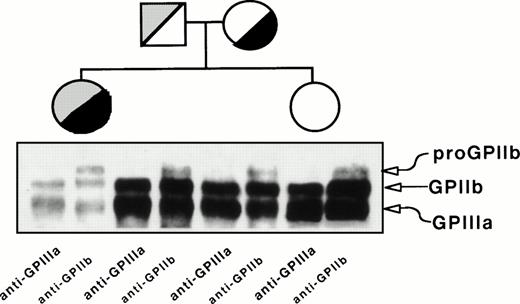

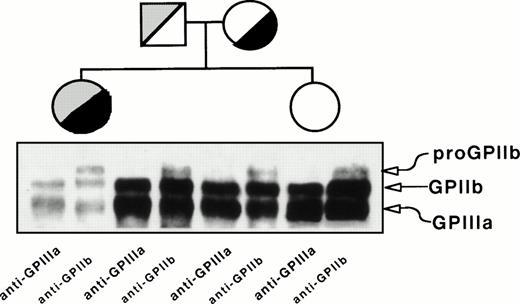

Figure 2 depicts the immunoprecipitation analysis of GPIIb-IIIa from platelet lysates using anti-GPIIIa (P37) or anti-GPIIb (M3) MoAbs. Both antibodies yielded bands migrating like GPIIIa and GPIIb, but a band migrating like proGPIIb was detected only with the anti-GPIIb MoAb. The density of GPIIb and GPIIIa bands is lower and the ratio of proGPIIb to GPIIb intensity is higher in the proband than in her relatives. This observation indicated that, whatever the molecular lesion(s) could be, the formation of GPIIb-IIIa complexes was not prevented. The parents showed similar pattern of bands, although less intense, than the sister of the proband whose surface GPIIb-IIIa content is normal (Fig 1).

Immunoprecipitation analysis of platelet GPIIb and GPIIIa from the proband, her mother, father, and sister. Proteins in total platelet lysates were labeled with biotin-NHS, and GPIIb-IIIa complexes were immunoprecipitated using MoAbs specific for GPIIIa (P37) or GPIIb (M3) and processed as described in Materials and Methods.

Immunoprecipitation analysis of platelet GPIIb and GPIIIa from the proband, her mother, father, and sister. Proteins in total platelet lysates were labeled with biotin-NHS, and GPIIb-IIIa complexes were immunoprecipitated using MoAbs specific for GPIIIa (P37) or GPIIb (M3) and processed as described in Materials and Methods.

Identification of GPIIb mutations.

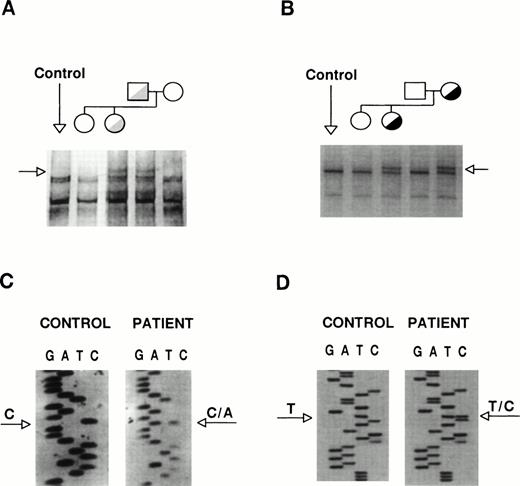

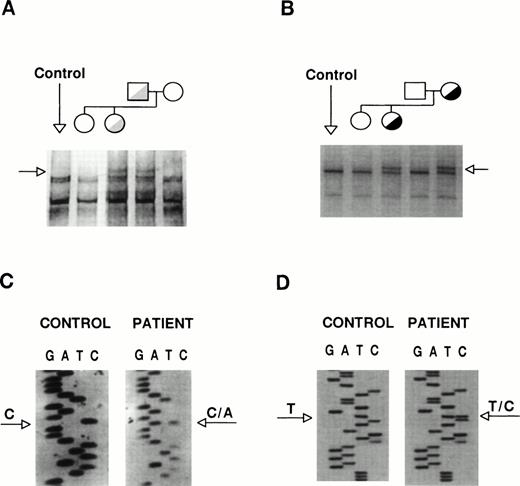

The coding sequences of GPIIb and GPIIIa were studied by SSCP analysis and almost entirely sequenced. The GPIIb exon 5 from the proband and her father showed distinct SSCP patterns (Fig 3A). Sequencing of exon 5 and its flanking regions showed the existence of a heterozygous C→A base substitution at position +2 of intron 5 (Fig 3C). This mutation, [IVS5(+2) C→A], changes the sequence of the donor splicing site of intron 5, predicting the incorporation of the unspliced intron (76 bp) into the mRNA, resulting in frameshift and premature polypeptide chain termination. The translational product of this messenger would be a truncated protein (∼30 kD) one third of the normal size. A second abnormal SSCP pattern was observed in exon 21 from the patient and her mother (Fig 3B), whose sequence identified a heterozygous T→C transition that changes Cys674→Arg (Fig 3D). The T2113→C transition creates a Fok I restriction site. None of these mutations was found in genomic DNA from more than 100 unrelated individuals, suggesting that they might be involved in the etiopathogenesis of the thrombasthenic phenotype. To verify the presence of these mutations and to assess the carrier status of kindred members, we performed allele-specific amplification (ASPCR) using antisense oligonucleotides whose 3′ end bases were complementary to either the normal or the mutant sequence of GPIIb intron 536 and restriction analysis of exon 21 (results not shown).

Identification of the patient mutations in genomic DNA. (A) A genomic DNA fragment of 442 bp comprising exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb was PCR-amplified, digested with Taq I, denatured, and used to search for mutations by SSCP analysis, using a 16% acrylamide-8.7% glycerol gel at 14°C. (B) A 193-bp genomic DNA fragment comprising exon 21 of GPIIb was subjected to SSCP analysis in a 14% acrylamide-8.7% glycerol gel at 15°C. The arrows point to distinct bands shown by the patient and her father or mother, respectively. (C) and (D) show fragments of the sequencing ladders of the sense strands (5′ at the bottom). The arrows point to a heterozygous C to A transversion at position +2 of exon 5-intron 5 boundary of GPIIb (C) and a T to C transition in exon 21 of GPIIb (D).

Identification of the patient mutations in genomic DNA. (A) A genomic DNA fragment of 442 bp comprising exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb was PCR-amplified, digested with Taq I, denatured, and used to search for mutations by SSCP analysis, using a 16% acrylamide-8.7% glycerol gel at 14°C. (B) A 193-bp genomic DNA fragment comprising exon 21 of GPIIb was subjected to SSCP analysis in a 14% acrylamide-8.7% glycerol gel at 15°C. The arrows point to distinct bands shown by the patient and her father or mother, respectively. (C) and (D) show fragments of the sequencing ladders of the sense strands (5′ at the bottom). The arrows point to a heterozygous C to A transversion at position +2 of exon 5-intron 5 boundary of GPIIb (C) and a T to C transition in exon 21 of GPIIb (D).

RT-PCR analysis of platelet mRNA-GPIIb.

The platelet contents of β-actin-mRNA, GPIIb-mRNA, and GPIIIa-mRNA were determined by the PCR-based TaqMan system24 under predetermined conditions of cycle number and amount of RNA in which the TaqMan fluorescence emission was a function of the target DNA concentration. The GPIIIa/β-actin ratio was similar to the control in all members of the family. In contrast, the GPIIb/β-actin ratio indicated that the platelet GPIIb-mRNA in the patient and her father was reduced to 52% and 67% of the control value, respectively (results not shown).

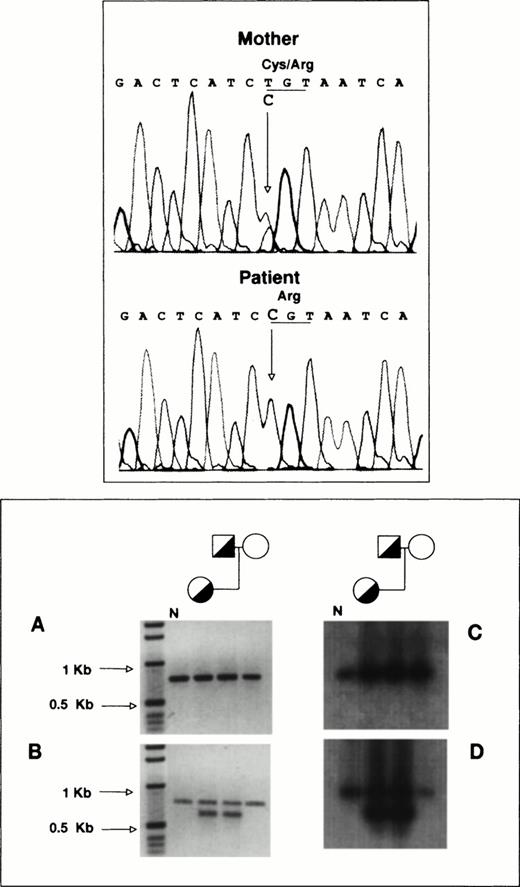

To determine the allelic origin of the GPIIb transcripts in the proband, we performed direct sequencing of a 1,190-bp PCR-amplified cDNA fragment encompassing exons 20 to 30, as described in Materials and Methods. Figure 4 (top panel) shows that the proband contains only a cytidine at nucleotide position 2113, whereas her mother, who is heterozygous for the T2113→C transition, shows in the same position a cytidine and a thymidine. According to this observation, virtually all of the proband’s GPIIb-mRNA is derived from the mother’s allele carrying the T2113→C substitution.

RT-PCR analysis of platelet GPIIb-mRNA. (Top panel) Total RNA from the proband and her mother was reverse-transcribed and used as template for the PCR amplification of a 1,190-bp fragment encompassing exons 20 to 30 of GPIIb as described in Materials and Methods. Direct DNA sequencing of the amplification products was performed in a model ABIprism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). (Bottom panel) (A) 779-bp DNA fragments encompassing exons 5 to 13 of GPIIb were amplified using as template reverse-transcribed platelet RNA as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Portions of the amplification products were reamplified using a sense primer complementary to sequences of intron 5 of GPIIb. (C) and (D) depict the hybridization analysis of the PCR products shown in (A) and (B), using a GPIIb probe lacking the oligonucleotide sequences used for amplification. N, PCR products from normal platelet RNA.

RT-PCR analysis of platelet GPIIb-mRNA. (Top panel) Total RNA from the proband and her mother was reverse-transcribed and used as template for the PCR amplification of a 1,190-bp fragment encompassing exons 20 to 30 of GPIIb as described in Materials and Methods. Direct DNA sequencing of the amplification products was performed in a model ABIprism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). (Bottom panel) (A) 779-bp DNA fragments encompassing exons 5 to 13 of GPIIb were amplified using as template reverse-transcribed platelet RNA as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Portions of the amplification products were reamplified using a sense primer complementary to sequences of intron 5 of GPIIb. (C) and (D) depict the hybridization analysis of the PCR products shown in (A) and (B), using a GPIIb probe lacking the oligonucleotide sequences used for amplification. N, PCR products from normal platelet RNA.

To analyze the effect of the IVS5(+2)C→A mutation on the mRNA processing, platelet total RNA from the proband and her relatives was reverse-transcribed with the oligonucleotide GPIIb (1305-1285), 5′-ACCCAGGAACACCAGCACTTG-3′, and used as template for the amplification of a 779-bp cDNA fragment encompassing exons 5 to 13. Figure 4A (bottom panel) shows a single DNA fragment of 779 bp from normal DNA (N), the proband, and her parents. The lack of amplification products other than the 779-bp fragment confirmed the absence or extremely low availability of transcripts from the IVS5(+2)C→A mutated allele as a result of either insertion of intron 5 (76 bp) or alternate splicing. This point was further investigated by reamplifying portions of the first PCR product with a sense primer complementary to a sequence of intron 5, GPIIb-(intron 5, 1-19) 5′-GCGAGTAGGGAGCAAAAGC-3′, that could only be found in transcripts from the mutant allele. This reamplification (Fig 4B, bottom panel) yielded a product of the same size as that of the primary PCR product, most probably due to carryover of the primary sense primer, and a new band of 727 bp seen only in the proband and her father. When the first PCR was performed with the sense primer for intron 5, there was no amplification. The identity of the amplification products shown in Fig 4A and B (bottom panel) was established by hybridization analysis using a GPIIb probe lacking the oligonucleotide sequences used for the PCR amplification. The two hybridization signals so obtained (Fig 4C and D, bottom panel) corresponded to the amplification products shown in Fig 4A and B. Sequencing of the 727-bp band showed that it was the result of insertion of intron 5 (76 bp) into the GPIIb-mRNA. The minute representation of this transcript indicates instability of the transcriptional product of the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele.

Exontrap analysis.

Because of initial difficulties in obtaining platelets from this kindred, we studied the influence of the [IVS5(+2)C→A]GPIIb mutation on the processing of mRNA by the exontrap analysis system. Figure 5 depicts the results obtained in the analysis of a fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 from either normal or mutant [IVS5(+2)C→A]GPIIb alleles in the expression vector pET01. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from CHO cells transiently transfected with the normal genomic DNA yielded a GPIIb fragment of 471 bp. In contrast, a 548-bp major product and a less abundant one of 481 bp were detected in cells transfected with mutant DNA. Sequencing of these products showed that the 471-bp fragment amplified from the control comprised exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb flanked by the pET01 exons. The major 548-bp product from cells transfected with the mutated cDNA was shown to be the result of insertion of intron 5 (76 bp) into the normal sequence. In the smaller product (481 bp), we found insertion of intron 5 and a partial deletion of exon 7 due to activation of a cryptic splicing site and recovery of the normal reading frame. The translation of this transcript would yield a mutated polypeptide similar in size to the normal GPIIb. However, this form of messenger was not detected by RT-PCR analysis in the proband’s platelet.

Exontrap analysis of a fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb. A fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb from the proband and a control were cloned in the expression vector pET01 and transfected into CHO cells as described in Materials and Methods. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the transfected cells yielded a fragment of 471 bp in the control and a product of 548 bp and a second smaller, less represented product of 481 bp in cells transfected with DNA from the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele of the proband. Sequencing of the amplification products demonstrated that the 471-bp fragment comprised exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb and the vector exons, the 548-bp fragment is the result of insertion of intron 5 into the normal sequence, and the 481-bp product has intron 5 inserted and exon 7 partially deleted.

Exontrap analysis of a fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb. A fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb from the proband and a control were cloned in the expression vector pET01 and transfected into CHO cells as described in Materials and Methods. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the transfected cells yielded a fragment of 471 bp in the control and a product of 548 bp and a second smaller, less represented product of 481 bp in cells transfected with DNA from the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele of the proband. Sequencing of the amplification products demonstrated that the 471-bp fragment comprised exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb and the vector exons, the 548-bp fragment is the result of insertion of intron 5 into the normal sequence, and the 481-bp product has intron 5 inserted and exon 7 partially deleted.

Heterologous expression of normal or mutated forms of GPIIb.

The low representation of transcripts from the [IVS5(+2)C→A]GPIIb allele suggested a poor functionality of its translational product. However, because the possibility existed that the abnormal GPIIb form could accumulate, we performed a heterologous overexpression of [intron 5]GPIIb to analyze its interaction with GPIIIa. CHO cells inherently expressing human GPIIIa (CHO-GPIIIa cells) were stably transfected with either the construct pCEP4-GPIIb or pCEP4-[intron 5]GPIIb. Cells transfected with the void plasmid showed surface expression of GPIIIa associated with endogenous alpha subunits (Fig 6A). Cells transfected with normal GPIIb showed surface exposure of GPIIb accompanied by a significant increase in the fluorescence signal of GPIIIa (Fig 6B), whereas no surface fluorescence changes in GPIIb-IIIa were observed in cells transfected with the mutant [intron 5]GPIIb cDNA (Fig 6C).

Flow cytometric analysis of CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNAs encoding normal or mutant [intron 5]GPIIb. CHO cells derived from hygromycin-resistant clones were analyzed for surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa by flow cytometry. The cells were incubated with either anti-GPIIb (M3) or anti-GPIIIa (P37) MoAbs and then treated with FITC-conjugated rabbit F(ab′) antimouse IgG. (A) Surface expression of GPIIIa and GPIIb in cells inherently expressing human recombinant GPIIIa (CHO-GPIIIa cells). (B) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding normal human GPIIb. (C) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding [intron 5]GPIIb. NC, negative control, fluorescence of cells incubated only with the second antibody.

Flow cytometric analysis of CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNAs encoding normal or mutant [intron 5]GPIIb. CHO cells derived from hygromycin-resistant clones were analyzed for surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa by flow cytometry. The cells were incubated with either anti-GPIIb (M3) or anti-GPIIIa (P37) MoAbs and then treated with FITC-conjugated rabbit F(ab′) antimouse IgG. (A) Surface expression of GPIIIa and GPIIb in cells inherently expressing human recombinant GPIIIa (CHO-GPIIIa cells). (B) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding normal human GPIIb. (C) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding [intron 5]GPIIb. NC, negative control, fluorescence of cells incubated only with the second antibody.

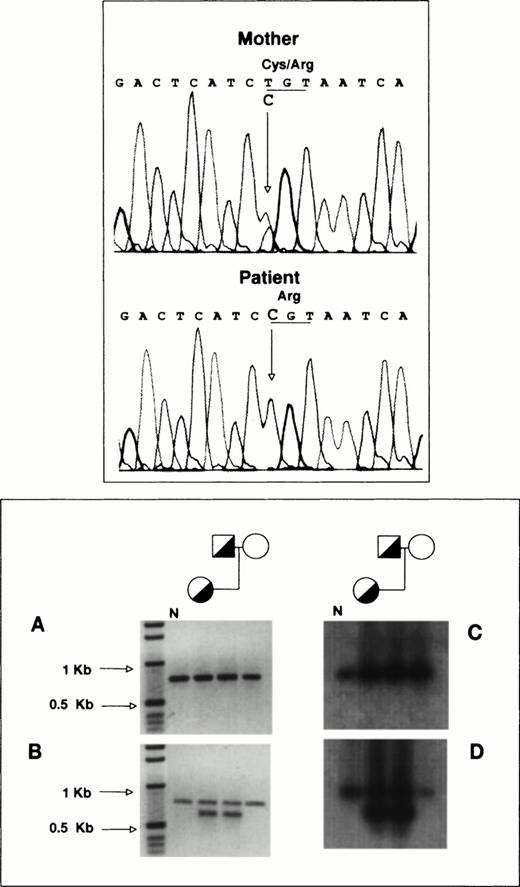

To analyze the function of the Cys674→Arg mutation, we performed transient cotransfections of CHO cells with pcDNA3 plasmids containing GPIIIa and either normal or mutant [C2113]GPIIb cDNA. The cells coexpressing normal GPIIb and GPIIIa showed surface exposure of GPIIb-IIIa complexes (Fig 7A), but surface expression was strongly attenuated in cells coexpressing normal GPIIIa with the mutant GPIIb (Fig 7A).

Immunoprecipitation analysis of GPIIb-IIIa complexes from CHO cells transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. CHO cells were transiently transfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. Surface (upper panel) or total (surface and intracellular, lower panel) labeling of cells was performed with biotin-NHS and the GPIIb-IIIa complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIIIa (P37) or anti-GPIIb (M3) MoAbs and processed as described in Materials and Methods.

Immunoprecipitation analysis of GPIIb-IIIa complexes from CHO cells transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. CHO cells were transiently transfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. Surface (upper panel) or total (surface and intracellular, lower panel) labeling of cells was performed with biotin-NHS and the GPIIb-IIIa complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIIIa (P37) or anti-GPIIb (M3) MoAbs and processed as described in Materials and Methods.

To estimate the intracellular GPIIb-IIIa content, we incubated total cell lysates with biotin before the immunoprecipitation procedure. The pattern of bands from cells coexpressing normal subunits was similar to that shown in surface labeled cells, except that proGPIIb was clearly identified when the immunoprecipitation was performed with the anti-GPIIb MoAb (Fig 7B). Immunoprecipitation of biotin-labeled lysates from cells coexpressing normal GPIIIa and mutant [Arg674]GPIIb with anti-GPIIb MoAb showed the presence of a clear proGPIIb band and weaker bands migrating like GPIIb and GPIIIa. When the anti-GPIIIa MoAb was used, GPIIIa and a faint band migrating like GPIIb were observed (Fig 7B). These observations agree with the platelet immunoprecipitation analysis and seem to suggest that [Arg674]GPIIb is able to complex GPIIIa, but it fails to maintain a normal rate of maturation and surface expression.

DISCUSSION

The low platelet GPIIb-IIIa complex (∼10%) and fibrinogen (23%) content indicate that the proband is a type II case of GT. The present study demonstrates that she inherited a splicing site mutation [IVS5(+2)C→A] from her father and a point mutation, a T2113→C transition that changes Cys674→Arg, from her mother and, therefore, is a compound heterozygote for the GPIIb gene (Fig 3). Both mutations cosegregate with reduced platelet content of GPIIb-IIIa and neither of them was found in genomic DNA from 100 normal unrelated individuals, ruling it out as being due to polymorphisms. As far as we know, this is the sixth reported case of a GPIIb mutation associated with type II GT.19 However, functional studies have been performed only in two of them.25,37,38 Theoretically, the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb mutation should lead to insertion of intron 5 into the mRNA resulting in a frame shift and appearance of a premature termination codon. This prediction was verified by exontrap analysis and, later on, confirmed by platelet GPIIb-mRNA sequencing. The presence of a premature stop codon is accompanied by changes in the amount of transcript. In our case, the extremely low amount of messenger from the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele is consistent with the idea that the amount of transcript is position related, so that the closer to the 5′ end of the coding sequence, the lower the amount of transcript.39 The β-thalassemia syndrome was the first reported case of a human disease associated with splicing junction mutations.40 Splice mutations in GPIIb or GPIIIa associated with thrombasthenic phenotypes have been recently reported.41-46 However, the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb mutation by itself cannot explain the thrombasthenic phenotype of the patient, because her father, who is also heterozygous for this mutation, shows a diminished platelet GPIIb-IIIa receptor but is clinically asymptomatic.

The patient shows a decreased (∼50%) platelet content of GPIIb-mRNA. The possibility that part of this messenger was formed by normal splicing of the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele, which could contribute to the platelet expression of GPIIb-IIIa receptor, is improbable. This assertion is based on the exclusive finding of the mutant [Arg674]GPIIb allele, inherited from her mother, in the direct sequencing of the PCR-amplified platelet GPIIb-cDNA from the patient.

The pathogenic significance of the [Arg674]GPIIb mutation is suggested by (1) its association with reduced platelet content of GPIIb-IIIa receptor in the heterozygous states; (2) very low surface exposure of GPIIb-IIIa receptors and elevated ratio of proGPIIb to GPIIb in the platelets from the proband who carries only the [Arg674]GPIIb-mRNA; and (3) accumulation of proGPIIb and failure to show a normal level of GPIIb-IIIa surface exposure when [Arg674]GPIIb was coexpressed with GPIIIa in CHO cells. These observations indicate that subunit dimerization is not prevented, but the maturation of GPIIb and/or intracellular transit proceeds at an abnormally low rate. Cys674 forms an intrachain disulfide bond with Cys687.47Because no mutations other than [Arg674]GPIIb have been found by RT-PCR analysis of GPIIb and GPIIIa-mRNAs in the proband and her mother, it seems plausible to assume that disruption of the intrachain 674-687 disulfide bond in GPIIb impedes the appropriate subunit conformation to confer either heterodimer stability and/or a normal rate of maturation and surface expression of the GPIIb-IIIa receptor. The endoproteolytic cleavage of GPIIb requires its association with GPIIIa.48 Thus, the increased intracellular proGPIIb to GPIIb ratio in either platelets or in cotransfected CHO cells may reflect either a limited availability of heterodimers or a decreased affinity of the cleavage enzyme(s) for the abnormal complexes. The failure to immunoprecipitate proGPIIb with an anti-GPIIIa MoAb in cells coexpressing GPIIIa and [Arg674]GPIIb (Fig 7B) seems to indicate an altered rate of association of pro[Arg674]GPIIb with GPIIIa. The functional importance of intrachain disulfide bonds in GPIIb-IIIa has been previously noticed. Deletion of Cys107, which forms the 107-130 intrachain disulfide bond in GPIIb,47 prevents heterodimerization and surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa complexes.49 Moreover, disruption of the 374-386 disulfide bond by substitution of Cys374 by Tyr in GPIIIa is associated with type II thrombasthenia.50 However, removal of Cys655 has no apparent effects on the surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa,51 indicating that not all of the highly conserved cysteine residues in this integrin are essential for the function of the complex.

The parents of the proband, who are heterozygous for the [IVS5(+2)C→A]GPIIb and the [C2113]GPIIb mutations, respectively, are both clinically asymptomatic and show a marked reduction in the platelet content of GPIIb-IIIa. A reduced expression of the platelet GPIIb-IIIa receptor has been observed in heterozygous states for other GPIIb mutations, but the recessive character of GT may be the reason for the lack of attention paid to the biochemical features of these clinically asymptomatic states. Two possibilities could be considered to explain the reduced platelet content of GPIIb-IIIa in the heterozygous states: (1) a quantitative or qualitative change in the mRNAs and (2) the translational products of mutated messengers could have distinct functional properties, as has been suggested before for other human diseases.52-56PCR-based determination showed a reduction of platelet GPIIb-mRNA in the proband and her father and a normal content in her mother. Because the contribution of the mutated [IVS5(+2)C→A]GPIIb allele to the total mRNA is negligible, the reduced platelet expression of GPIIb-IIIa receptor seems to correlate with a decreased availability of messenger in the proband’s father. At least 50% of the platelet GPIIb-mRNA is accounted for by the mutated [T2113]GPIIb allele in the proband’s mother. Thus, the diminished platelet GPIIb-IIIa receptor in both heterozygous states seems to correlate with a reduced availability of normal GPIIb messenger. Nevertheless, the differences in the surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa in both cases, taken together with the repression of the GPIIIa surface exposure associated with endogenous subunits by the mutated [Arg674]GPIIb (results not shown), suggest the operation of mechanisms other than mRNAs availability in controlling the surface exposure of the GPIIb-IIIa receptor.

To conclude, this work reports a case of a compound heterozygote for the GPIIb gene associated with type II GT. The proband presents two novel GPIIb mutations: a heterozygous C→A base substitution at position +2 of the exon 5-intron 5 boundary [IVS5(+2)C→A], and a T2113→C transition that changes Cys674→Arg674 disrupting the 674-687 intrachain disulfide bond. The following observations support the etiopathogenic significance of these two mutations: (1) Neither of them was found in a large number of normal unrelated individuals. (2) The clinically asymptomatic heterozygous states for each of these mutations show reduced platelet content of GPIIb-IIIa. (3) Cotransfection of cDNAs encoding normal GPIIIa and [Arg674]GPIIb showed accumulation of proGPIIb and markedly diminished surface exposure of GPIIb-IIIa. Thus, the thrombasthenic phenotype of the patient is the result of the additive effect of both mutations. The splicing junction mutation acts primarily by limiting the availability of GPIIb-mRNA, whereas the translational product of [C2113]GPIIb forms heterodimers with GPIIIa unable to undergoing the pathway of maturation, intracellular trafficking, and/or membrane assembly at normal rates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr N. Kieffer for the gift of the CHO-GPIIIa cells.

Supported in part by grants from Dirección General de Investigación Cientı́fica y Técnica (PB94-1544), Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (96/2014), CAM: CO7191, and European Community concerted action contract no. BMH1-CT93-1685. M.F.-P., M.F., and E.G.A.-S. were recipients of predoctoral fellowships from the Council of Research of the Autonomous Community of Madrid, the Spanish Secretary of Education and Science, and the Fundación Areces, respectively.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Roberto Parrilla, MD, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas (CSIC), Velázquez 144, 28006-Madrid, Spain; e-mail: rparrilla@fresno.csic.es.

![Fig. 5. Exontrap analysis of a fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb. A fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb from the proband and a control were cloned in the expression vector pET01 and transfected into CHO cells as described in Materials and Methods. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the transfected cells yielded a fragment of 471 bp in the control and a product of 548 bp and a second smaller, less represented product of 481 bp in cells transfected with DNA from the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele of the proband. Sequencing of the amplification products demonstrated that the 471-bp fragment comprised exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb and the vector exons, the 548-bp fragment is the result of insertion of intron 5 into the normal sequence, and the 481-bp product has intron 5 inserted and exon 7 partially deleted.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.866/5/m_blod40311005y.jpeg?Expires=1767740727&Signature=TP73fjwYofkXZwwbXd8CcEIpTFWdEFab8drcw-rMj4vQnZlWLuRQbJbs6ePyQzY6K9UV9Q~HGYR-1z1DxaarckmVJ3qdgRmUMCotQMDriPgGkqIfuFgwn3c3HfyRKjYpRCQdm3wuNdDRmDSg-Ni08heObF9T-DS4~CyhK9Glze7nhTeR0OW4suxux4pXlfO4WQSrZLm4trqZ5DfXK5tYZ7NKbzy5xCvYopiRAL6KDrEiTTJtHLaTcmJ2-rPWGrRJHZILJdbG3~hhd7~itSALuNONHhUpjGOjSQVssAQD~qSSlrlBahcHKZMhNaUUFocMcZjdcZWiUQ2cE-ZnWMub2g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. Flow cytometric analysis of CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNAs encoding normal or mutant [intron 5]GPIIb. CHO cells derived from hygromycin-resistant clones were analyzed for surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa by flow cytometry. The cells were incubated with either anti-GPIIb (M3) or anti-GPIIIa (P37) MoAbs and then treated with FITC-conjugated rabbit F(ab′) antimouse IgG. (A) Surface expression of GPIIIa and GPIIb in cells inherently expressing human recombinant GPIIIa (CHO-GPIIIa cells). (B) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding normal human GPIIb. (C) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding [intron 5]GPIIb. NC, negative control, fluorescence of cells incubated only with the second antibody.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.866/5/m_blod40311006x.jpeg?Expires=1767740727&Signature=Gp-k4oKM25qRHI6Wh-tTsxIJmELUBZdgNneoZsgdmWQX0GJU7leXY4VbyNWoy3BYFnjBCuqkGcihJW9~qtCY99T7BUyIkltx1hieUJctqihJRwiKY9rjYCga7XBEM7kgWe7jG2PM4qlh6Z2tSp~TxnFsTw77mqmCdkn36y2bt0BLNuWdTK4lMaQSW8ND4vphmVsi4x0ax~SfPpkjPHtNujBkkhXazVwrvCrkha-vDg5j~-TG7uuh4MDl1uePnwmPmgO1UZkB78uhf2AKy4TcszO0Im6IuBVUQsyzP-JP6MLou2a7oL4QfjENXR6khcUQNX7mbmIOmC8I0K04tEKCXQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 7. Immunoprecipitation analysis of GPIIb-IIIa complexes from CHO cells transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. CHO cells were transiently transfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. Surface (upper panel) or total (surface and intracellular, lower panel) labeling of cells was performed with biotin-NHS and the GPIIb-IIIa complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIIIa (P37) or anti-GPIIb (M3) MoAbs and processed as described in Materials and Methods.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.866/5/m_blod40311007w.jpeg?Expires=1767740727&Signature=MbbfGEBTm-cUpH4-KNJIvHGECwHJM5sqCwepYheU4BC8~E2UI0dUJHeMnYYE14xY6s4gTbmBrmnK-Xfp2fc~Jwy7eFN2YMQXD-pGRhSVrX2WlbNXR5kmv7n-Y9BjF1dX-lhv4y9BPvt71cn6rnrBpSwu3NSAfd4q88IEOGpJhD5WOVzc7FYhYkssxJ8AabgRTQXEdvOTOwF3bc0CJZ4-nj3f~9fr~-U0aYvVEwT2wEY1OgVrWK2b8rFLWBXV-GN6obwrZU6gvMvltyc23~UTNXrCrDlGeQ39t9de4KqdorkhwRgZyVQ~sxClJSxATlMB5ng6Xil-Ko9-BnCc7skCVA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. Exontrap analysis of a fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb. A fragment of genomic DNA encompassing exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb from the proband and a control were cloned in the expression vector pET01 and transfected into CHO cells as described in Materials and Methods. RT-PCR analysis of RNA from the transfected cells yielded a fragment of 471 bp in the control and a product of 548 bp and a second smaller, less represented product of 481 bp in cells transfected with DNA from the [IVS5(+2)C→A]-GPIIb allele of the proband. Sequencing of the amplification products demonstrated that the 471-bp fragment comprised exons 5 to 7 of GPIIb and the vector exons, the 548-bp fragment is the result of insertion of intron 5 into the normal sequence, and the 481-bp product has intron 5 inserted and exon 7 partially deleted.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.866/5/m_blod40311005y.jpeg?Expires=1768126898&Signature=COGMyPEGis4Tu4pOGVBZemewfuy57BwyXzg0Dgn6ziIFrcrQDsVpnD3cKxBLJHJdC3XEwE0Jo2OnagGehwMdtUkSnB2dp3RLKpH7CIWNAB-dYZtGF1fkrLCMPoFtQ0CpTf4h7ucCIN2xaVkSSw6ZlpYi2EmT8t~g29kMbVL1Kg31Z7oOn40iA6SJydD7EK7wMzM1os53Uy~xoTB7WTrGAa27xVG2CZ~vD1ow4x0aILrfeAAMHc2MI9uuzHe1EkmdmmNobKcng0E7E5MdqrjxhKAoAJocM0JaUnxQm8KM1iEZsql35CvfLnJnjPbnps1Wu7q8QyjHIR9LgUp5jYDqtw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. Flow cytometric analysis of CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNAs encoding normal or mutant [intron 5]GPIIb. CHO cells derived from hygromycin-resistant clones were analyzed for surface expression of GPIIb-IIIa by flow cytometry. The cells were incubated with either anti-GPIIb (M3) or anti-GPIIIa (P37) MoAbs and then treated with FITC-conjugated rabbit F(ab′) antimouse IgG. (A) Surface expression of GPIIIa and GPIIb in cells inherently expressing human recombinant GPIIIa (CHO-GPIIIa cells). (B) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding normal human GPIIb. (C) Surface expression of GPIIb and GPIIIa in CHO-GPIIIa cells stably transfected with cDNA encoding [intron 5]GPIIb. NC, negative control, fluorescence of cells incubated only with the second antibody.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.866/5/m_blod40311006x.jpeg?Expires=1768126898&Signature=tnXASn4oVGFw4RNaLr~qTLNDevh69netsaSlxMEIBGOqBJXta6wt9HiaEj3mq1jaWw2l0~I3Pq3BwoapJtl6DMKBxNCZ6nZsP6V8teOBmNU4t~gjf35bh5kIwROZCAiI6jH6sPUulmU~pWLnZediM55TSFJZHZK5jwLdYBUZbD9zmTF1aVQ~KIWeWBfcvfsG-IyAd54dfWJlfnlHGMkXlJXRlVNTte13SP8i-W3hWkD0tZvEJGU~Fz~cwygDFnbu4v7PdnGWjj0c0YFtqaAtmSEtG1NoEpbG6rbPbYnhtNFjIfG5QSqHpINdVy11JsaNWEA7hxjdiQ~JUI0BqpmTSg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 7. Immunoprecipitation analysis of GPIIb-IIIa complexes from CHO cells transiently cotransfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. CHO cells were transiently transfected with cDNAs encoding GPIIIa and either normal or [Arg674]GPIIb. Surface (upper panel) or total (surface and intracellular, lower panel) labeling of cells was performed with biotin-NHS and the GPIIb-IIIa complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti-GPIIIa (P37) or anti-GPIIb (M3) MoAbs and processed as described in Materials and Methods.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.866/5/m_blod40311007w.jpeg?Expires=1768126898&Signature=Ovm1ChlBkgxbYhfKGC56NSP64b2Ruu6HPqqkcUBMor5kMlXoR78zh5044I7EFvcdm3dYsN3fcEPjM13AgCRW3ktE50pwfhU-~WISCjFHdZLM1zW3FhbZUfESPX9RDkYQeqq~Hkg-G0YEhQm~uPBrdBYPhvrNO3aoBCyw1PtqODSG4OecoPkryZ1xnjpSucPN~pv9LvNvtL4rEHv0a-GmuLu1oTXgnjx~eCLo8Yd7OisG6HSxqvomnx3Xgk88LRjpQ5JYcQizFVfYQUBOVFHCrrI7ofgg0XERYVLW5lyA2jkm12IRKgVasN02O1~1ZBsyc8O2Udz-gYfngpmG40H0FA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)