Abstract

Polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) adhesion to activated platelets is important for the recruitment of PMN at sites of vascular damage and thrombus formation. We have recently shown that binding of activated platelets to PMN in mixed cell suspensions under shear involves P-selectin and the activated β2-integrin CD11b/CD18. Integrin activation required signaling mechanisms that were sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors.1 Here we show that mixing activated, paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed platelets with PMNs under shear conditions leads to rapid and fully reversible tyrosine phosphorylation of a prominent protein of 110 kD (P∼110). Phosphorylation was both Ca2+ and Mg2+ dependent and was blocked by antibodies against P-selectin or CD11b/CD18, suggesting that both adhesion molecules need to engage with their respective ligands to trigger phosphorylation of P∼110. The inhibition of P∼110 phosphorylation by tyrosine kinase inhibitors correlates with the inhibition of platelet/PMN aggregation. Similar effects were observed when platelets were substituted by P-selectin–transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-P) cells or when PMN were stimulated with P-selectin–IgG fusion protein. CHO-P/PMN mixed-cell aggregation and P-selectin–IgG–triggered PMN/PMN aggregation as well as P∼110 phosphorylation were all blocked by antibodies against P-selectin or CD18. In each case PMN adhesion was sensitive to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein. The antibody PL-1 against P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) blocked platelet/PMN aggregation, indicating that PSGL-1 was the major tethering ligand for P-selectin in this experimental system. Moreover, engagement of PSGL-1 with a nonadhesion blocking antibody triggered β2-integrin–dependent genistein-sensitive aggregation as well as tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. This study shows that binding of P-selectin to PSGL-1 triggers tyrosine kinase–dependent mechanisms that lead to CD11b/CD18 activation in PMN. The availability of the β2-integrin to engage with its ligands on the neighboring cells is necessary for the tyrosine phosphorylation of P∼110.

THE BINDING OF polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) to activated platelets in mixed-cell suspensions under high-speed rotatory motion can be modeled as an adhesion cascade involving a P-selectin–dependent recognition step followed by an adhesion-strengthening interaction mediated by CD11b/CD18.1As platelet-PMN adhesion was prevented by tyrosine kinases inhibitors, an intermediate tyrosine kinase–dependent signal regulating β2-integrin adhesiveness was postulated.1 The multistep adhesion cascade was first characterized for PMN adhesion to the endothelium.2,3 In this model, the selectin-mediated rolling movement culminates in the firm adhesion sustained by the binding of intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAMs) expressed on the endothelial surface to β2-integrins on PMN.2,3 At variance with the adhesive molecules involved in the rolling step that do not require an activation signal to recognize the ligand, β2-integrins require a functional upregulation to become competent to bind their counter-receptor.4 This implies that an intermediate β2-integrin–activating signal is delivered from the endothelial cell surface to PMN in the few seconds between rolling movement and firm attachment. To explain this signaling two possibilities not excluding each other have been reported in the literature. The first is that tethering by selectins allows a juxtacrine-activating signal by lipid autacoids and chemoattractants bound on endothelial cell membrane.5 The second possibility is that selectin binding to PMN may, per se, induce Mac-1 activation,6-8 although conflicting results have been reported.9

In addition to PMN adhesion to the endothelium,2,3 a similar, well-characterized, multistep model has been recently shown for adhesion of flowing PMN over surface-adherent platelets.10-14 This phenomenon may have pathophysiological relevance, because platelets activated at the site of vascular damage could play an important role in leukocyte recruitment in a growing thrombus,15,16 where accumulated leukocytes can contribute to increase fibrin deposition.15Activated platelets adhering to the surface of a damaged vessel could substitute endothelial cells in allowing recruitment and migration of leukocytes through the vessel wall.13 These events on one hand may contribute to the maintenance of the vascular and tissue integrity and on the other may play a pathogenetic role in inflammatory and thrombotic disease. Indeed, activated platelets express not only P-selectin but also different β2-integrin ligands including fibrinogen17,18 and ICAM-2.19Moreover, activated platelets can release platelet-activating factor (PAF), adenine nucleotides, and the CXC chemokines ENA-78, GRO-α,20 and the neutrophil-activating peptide-2 (NAP-2).21,22 All these platelet-derived products are potent PMN agonists and some of them may be involved in β2-integrin–dependent arrest of PMN on surface-adherent platelets.14 Previous experimental evidence shows that P-selectin, alone23-25 or in combination with chemokines,26,27 is able to stimulate different responses by leukocytes, suggesting that some of these responses are directly triggered by the adhesive molecules whereas others require integration with additional signals elicited by chemokines. Experimental evidence includes the observation that P-selectin may per se stimulate CD11b/CD18-dependent phagocytosis by PMN,28 although conflicting results have been reported.29 The functional responses elicited by P-selectin on leukocytes could be prevented by specific antibody to the cloned30,31 P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1), indicating that this adhesive receptor is able to transduce an “outside-in” signal when engaged by the ligand.27 This concept was recently strengthened by the observation that engagement of PSGL-1 on PMN, per se, induced protein-tyrosine phosphorylation, activated MAP kinases, and stimulated interleukin-8 secretion.32 More recently Blanks et al showed that PSGL-1 engagement on mouse but not on human PMN induces LFA-1 and Mac-1–dependent adhesion to ICAM-1.33

Altogether these observations left open the question whether P-selectin is directly or indirectly involved in the mechanisms allowing activated platelets to stimulate the tyrosine kinase–dependent adhesiveness of Mac-1 that mediates aggregation of PMN and platelets. In the present study using activated platelets, P-selectin expressing Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO-P) and soluble recombinant P-selectin, we addressed the question whether P-selectin was able to trigger protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN as well as the tyrosine kinase(s)–dependent function of the β2-integrin Mac-1. Finally, we investigated the possible role of the cloned P-selectin receptor, PSGL-1, in this phenomenon.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

Hydroethidine (HE) was purchased from Molecular Probes Europe (Leiden, The Netherlands); 2′, 7′-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxy-fluorescein triacetoxy methyl ester (BCECF-AM), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antimouse IgG (whole molecule), FITC-conjugated anti-human CD11b monoclonal antibody (clone 44), F(ab)” fragments of sheep anti-mouse IgG, n-formyl-Methyl-Leucyl-Phenylalanine (fMLP), prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), phorbol 12-myristate, 13 acetate (PMA), N-2 hydroxyethyl piperazine-N 1-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) ethylene glycol-bis (b-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N′, N′,-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), thrombin from human plasma (2,000 National Institute of Health [NIH] U/mg of protein), the kinases inhibitors genistein, erbstatin A, and 1-(5-isoquinolinylsulfonyl)2-methylpiperazine (H-7) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO), and deionized water was purchased from Merck (Milano, Italy). Paraformaldehyde (PFA) was purchased from Fluka (Milano, Italy). Dextran T500 and Ficoll-Hypaque were from Pharmacia Fine Chemicals (Uppsala, Sweden) and Aldrich Chimica srl (Milano, Italy). fMLP was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentrations of 100 mol/L, stored at −20°C, and diluted in isotonic saline just before use. Thrombin was dissolved in saline at concentrations of 50 U/mL and stored at −20°C until use. BCECF-AM and HE were dissolved in DMSO at concentrations of 1 mg/mL and 8 mg/mL, respectively, stored at −20°C, and used within 4 weeks. The MEK inhibitor PD98059 is from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). The R-PE conjugate anti-human CD62P (clone CBL 474P) was purchased from Serotec (Milano, Italy). The recombinant horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (MoAb) RC20 was from Transduction Laboratories (Exeter, UK). Enhanced ChemiLuminescence Western blotting system (ECL-kit) was from Amersham Life Science (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Reagents for electrophoresis and Western blot analysis were pure grade.

Antibodies.

The following MoAbs were kindly provided: the anti-P-selectin WAPS 12.234 and the anti–L-selectin DREG-56 and DREG-20035 by Dr Eugene C. Butcher (Foothall Research Center, Stanford University, CA), the anti–ICAM-2 B-T1 and B-R736 by Dr Carl G. Gahmberg (Department of Bioscience, University of Helsinky, Helsinky, Finland), the anti–PSGL-1 PL1 and PL237 by Drs Kevin L. Moore and Roger P. McEver (WK Warren Medical Research Institute, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City), the anti-CD18, 60.338 by Dr John Harlan (University of Washington, School of Medicine, Seattle), P18 and P2 recognizing αvβ3 and αIIbβ3,39 respectively, by Dr John L. McGregor (INSERM, Unité 331, Lyon, France), the anti-CD11b Ab 44 by Dr Nancy Hogg (Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London, UK), and LPM19c, an anti-CD11b,40 by Dr Karen Pulford (University of Oxford, Oxford, UK).

The anti-CD11a, TS1/22,41 the anti-CD18, IB4 (American Tissue Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), and the anti-CD11c, HC1.142 (kindly provided by Dr Carmelo Bernabeu, Centro de Investigationes Biologicas, Madrid, Spain) were purified from mouse ascites or hybridoma cell supernantant using protein G-sepharose affinity column.

The construction of the P-selectin–IgG fusion protein has been described.43

Preparation of PMN leukocytes and of platelets and culture of CHO cells.

Blood was collected from healthy volunteers who had not received any medication for at least 2 weeks. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for these studies. Volunteers were informed that blood samples were obtained for research purposes and that their privacy would be protected. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared by centrifugation of citrated blood at 200g for 15 minutes. PMN, isolated from the remaining blood by Dextran sedimentation followed by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient and hypotonic lysis of erythrocytes, were washed and resuspended in ice-cold HEPES-Tyrode buffer (pH 7.4) containing 129 mmol/L NaCl, 9.9 mmol/L NaHCO3, 2.8 mmol/L KCl, 0.8 mmol/L KH2PO4, 5.6 mmol/L dextrose, 10 mmol/L HEPES. Immediately before the experiment 1 mmol/L MgCl2 and 1 mmol/L CaCl2 were added to the cells. All the procedures for PMN isolation were performed at 4°C. Cellular suspensions contained 95% of PMN and an average of 1 platelet/30 PMN. For adhesion experiments PMN were stained with the vital red fluorescent dye HE (20 μg/ 5 × 107PMN/mL) for 30 minutes at 4°C as previously reported.1

PFA-fixed resting, thrombin-activated unloaded, or BCECF-loaded platelets were prepared as previously described.1

Wild-type CHO or CHO stably transfected with the cDNA encoding for human P-selectin (CHO-P) were kindly provided by Genetics Institute, Cambridge, MA, and cultured as previously reported.44Immediately before the experiments, CHO and CHO-P cells were detached by incubating the monolayer with 5 mmol/L of both EGTA and EDTA for 10 minutes, washed twice in Hepes Tyrode, and resuspended in the same buffer at the concentration of 107/mL.

Cytofluorimetric analysis of P-selectin expression on platelets and CHO cells.

P-selectin expression on platelets and CHO cells was evaluated by indirect immunoflurescence using WAPS 12.2. As already reported,1 in our experimental conditions about 50% of unstimulated washed platelets express very low levels of P-selectin (MF 20) as compared with thrombin-activated platelets (100% positive with a MF of 185). CHO-P cells express high amount of P-selectin (83 ± 5% of the total population showed a mean fluorescence intensity of 388 ± 110 [mean ± SEM, n = 5]). Wild-type CHO cells did not bind the anti–P-selectin antibody.

Experimental conditions.

All the experiments have been performed in the following standard conditions: PMN alone or mixed with platelets (ratio 1/5 or 1/10) or with CHO cells (ratio 5/1) were incubated in a final volume of 500 μL in siliconized glass tubes (internal diameter 6 mm; ChronoLog, Mascia Brunelli, Milano, Italy). The tubes were placed in an aggregometer (Platelet Ionized Calcium Aggregometer, PICA, ChronoLog, Mascia Brunelli) at 37°C with stirring (1,000 rpm) obtained by an iron bar (4 mm long) rotating under a magnetic field. Although the shear rate produced by this stirring speed cannot be precisely quantified, it should approximate 250/s.45

This experimental condition allowed clear highlighting of the essential role of the β2-integrin CD11b/CD18 in mediating PMN/platelet adhesion.1

For blocking studies, antibodies were preincubated at saturating concentration (20 μg/mL) with the desired cell fraction for 15 minutes at 4°C.

Protein kinase inhibitors or the diluent (DMSO) were preincubated with PMN 2 minutes at room temperature before mixing with platelets, CHO cells, or P-selectin chimeras.

Double-color cytofluorimetric assay of PMN adhesion to platelets or CHO cells in suspension.

The previously described methodology1 was used to evaluate PMN-platelet adhesion. Briefly, BCECF-loaded platelets and HE-PMN mixed-cell population were incubated in standard conditions. The interaction was stopped at different times by addition of one volume of PFA 2%, and samples were kept at 4°C in the dark and analyzed by flow cytometry within 1 hour.

PMN adhesion to CHO cells was evaluated in similar manner. HE-loaded CHO cells were incubated with unloaded PMN in standard conditions. The interaction was stopped at different times by addition of one volume of PFA 2%, and cells were fixed for 30 minutes. After fixation, mixed-cell populations were incubated for additional 30 minutes with FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b antibody, which does not bind CHO cells, to stain the PMN and kept at 4°C in the dark before flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry.

To evaluate PMN/platelet adhesion, PMN were identified on the basis of forward and side scatter alone or in combination with the specific red fluorescent marker. Gating on events identified as PMN was performed to exclude single platelets. For each experiment a sample in which thrombin-activated platelets were mixed with PMN in the presence of 10 mmol/L EGTA was used to set a threshold on the green fluorescence scale (FL1; 90% of events below the threshold) to identify PMN showing the platelet green marker fluorescence.

The percentage of PMN showing the platelet marker, ie, above the threshold, represents the percentage of PMN binding platelets [PMN(+)%].

Platelet adhesion to PMN was also quantified by evaluating the relative number of platelets bound to 100 PMN (PLT/100 PMN).1

To evaluate PMN/CHO cells adhesion, CHO cells were identified on the basis of the specific red fluorescent marker. Gating on events identified as CHO cells was performed to exclude single PMN. For each experiment a sample in which CHO cells were mixed with PMN in the presence of 10 mmol/L EGTA was used to set a threshold on the green fluorescence scale (FL1; 90% of events below the threshold) to identify CHO cells showing the PMN green marker fluorescence.

The percentage of CHO cells showing the PMN marker, ie, above the threshold, represents the percentage of CHO cells binding PMN [CHO(+)%]. In preliminary experiments the CHO cells adhesion to PMN was also evaluated by optical microscopy counting the number of CHO cells carrying PMN and the number of free, nonadherent PMN. The latter number gives a precise value of the percentage of PMN involved in the formation of mixed-cell aggregates. PMN incubated with CHO-P cells in standard conditions formed mixed aggregates in which single CHO-P appeared surrounded by several PMN. Sometimes more than one CHO-P cells formed mixed aggregates with PMN. Similarly to what was observed with platelets, PMN adhesion to P-selectin expressing CHO cells was transient, reaching a maximum at 3 minutes after the start of stirring. At this time about 60% of CHO-P cells and 70% of PMN were involved in forming mixed aggregates. The interaction of wild-type CHO cells with PMN was negligible.

PMN homologous aggregation.

PMN aggregation represents an homologous cell-cell adhesion that is essentially mediated by β2-integrins, particularly by CD11b/CD18.46 47 For this reason, PMN aggregation can be considered a specific index of the functional upregulation of this integrin. Accordingly, in this study we evaluated the effect of soluble P-selectin–IgG chimera as well as the effect of the engagement of PSGL-1 with MoAb on PMN aggregation.

PMN (5 × 106/mL) were incubated in standard conditions with the P-selectin–IgG chimera. The reaction was stopped at different times by adding one volume of the cells to one volume of PFA 2%. After fixation, PMN aggregation was evaluated by counting the number of free, nonaggregated PMN (single PMN) by optical microscopy. In preliminary experiments, a dose-response curve showed that maximal PMN aggregation was induced by 10 μg/mL of P-selectin–IgG chimera. For this reason this concentration was used for all subsequent experiments. At this concentration the chimera did not aggregate PFA-fixed PMN, excluding that multimers of the protein agglutinate the cells in an activation-independent manner. P-selectin–IgG chimera contains the Fc portion of the human IgG. To exclude a possible effect of this portion mediated by the Fc receptor on PMN, we used nonimmune human IgG at concentration of 50 μg/mL as control material. Because human IgG has no effect, we decided to challenge PMN with the P-selectin chimera in the presence of human IgG to compete for the Fc receptors.

The effect of antibody-mediated engagement of PSGL-1 on PMN aggregation was evaluated by preincubating for 15 minutes at 4°C, 5 × 106 PMN with 20 μg of the noninhibitory anti–PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody PL2. After preincubation PMN were rapidly centrifuged to remove unbound antibody, resuspended, and incubated in standard conditions in the absence or in the presence of 10 μg/mL of anti-mouse F(ab)2 fragments. In these experiments the anti-CD11c antibody HC1.1 was used as control. The reaction was stopped at different times by adding one volume of the cells to one volume of PFA 2%. After fixation PMN aggregation was evaluated by counting the number of free, nonaggregated PMN.

Tyrosine phosphorylation experiments.

PMN were incubated alone or with platelets (ratio 1:5), CHO cells (ratio 5:1), P-selectin–IgG chimera (10 μg/mL), or with anti–PSGL-1 antibodies in the absence or presence of anti-mouse F(ab)2fragments or with fMLP (1μmol/L) exactly as described for adhesion experiments. The reaction was stopped at different times after initiation of stirring at 37°C by adding one volume of the cells to an equal volume of 2× reducing Laemmli’s buffer, added with 2 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 5 mmol/L EGTA, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 10 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mmol/L iodoacetic acid, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 mmol/L sodium fluoride, 10 μg/mL leupeptin and aprotinin, 1 mg/mL trypsin-chymotrypsin inhibitor. Samples were boiled for 10 minutes and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 7,000g. Aliquots of 100 μL, corresponding to 1.25 × 106 total PMN lysate, were loaded into 7.5% to 12.5% gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (SDS-PAGE). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose sheets and nonspecific sites blocked using 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline overnight at room temperature on a horizontal shaker. The nitrocellulose sheets were then incubated with the recombinant horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-phosphotyrosine antibody RC20 (0.1 μg/mL, 30 minutes at 37°C). Detection was performed by chemiluminescence using ECL-kit. Phosphotyrosine bands were visualised by autoradiography. For each experiment, basal level of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation was assessed on unstimulated PMN. Selected autoradiograms were analyzed using a UltroScan XL densitometer (LKB Instr, Stockholm, Sweden), and values in arbitrary units were corrected for background.

RESULTS

Adhesion to activated platelets stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN.

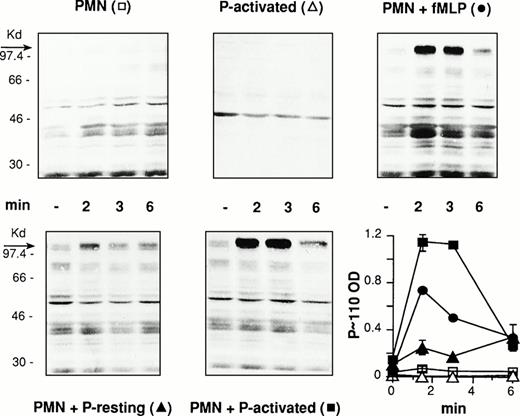

PMN and PFA-fixed resting or thrombin-activated platelets were incubated alone or combined at 37°C and 1,000 rpm stirring. In parallel, PMN were challenged with 1 μmol/L of fMLP for comparison. The interaction was stopped at different times by adding cells to boiling, SDS containing gel-loading buffer and cell lysates was processed for the analysis of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. Antiphosphotyrosine immunoblotting of whole cell lysates from activated platelet/PMN mixed-cell suspensions showed rapid and completely reversible tyrosine phosphorylation of a protein of molecular weight between 97 and 116 kD (P∼110). Increased tyrosine phosphorylation of additional proteins with relative molecular masses around 80 and 40 kD were also occasionally observed. Accordingly, we decided to evaluate tyrosine phosphorylation of this protein as a marker of tyrosine kinase(s) activation in PMN triggered by platelet adhesion. As expected, lysates from PMN or activated platelets incubated alone did not show any change in the pattern of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins, whereas stimulation of PMN by fMLP resulted in increased tyrosine phosphorylation of different proteins and in the appearance of a tyrosine phosphorylated protein at 110 kD (Fig1). This shows that the tyrosine-phosphorylated P∼110, found in activated platelet/PMN mixed-cell populations, belongs to PMN and undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation as a consequence of cell-cell interaction.

Activated platelets induce protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. PFA-fixed thrombin-activated platelets alone (P-activated), PMN alone or combined with PFA-fixed resting (P-resting), or thrombin-activated (P-activated) platelets at a ratio of 1:5 were incubated for different times at 37°C and stirring at 1,000 rpm (standard conditions). In parallel experiments PMN were challenged with fMLP (1 μmol/L) for comparison. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative experiment and the graph reports the optical density (in arbitrary units) of the major tyrosine-phosphorylated protein showing a relative molecular mass between 97 and 116 kD (P∼110) in the corresponding samples (symbols in brackets). Values are means ± SEM, n = 3.

Activated platelets induce protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. PFA-fixed thrombin-activated platelets alone (P-activated), PMN alone or combined with PFA-fixed resting (P-resting), or thrombin-activated (P-activated) platelets at a ratio of 1:5 were incubated for different times at 37°C and stirring at 1,000 rpm (standard conditions). In parallel experiments PMN were challenged with fMLP (1 μmol/L) for comparison. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative experiment and the graph reports the optical density (in arbitrary units) of the major tyrosine-phosphorylated protein showing a relative molecular mass between 97 and 116 kD (P∼110) in the corresponding samples (symbols in brackets). Values are means ± SEM, n = 3.

Protein-tyrosine phosphorylation is required for activated platelet/PMN adhesion.

The functional relationship between protein-tyrosine phosphorylation and cell-cell adhesion was investigated using tyrosine kinase(s) inhibitors. As shown in Fig 2A, the dose-dependent inhibition by genistein of P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation clearly correlates with inhibition of adhesion. Another tyrosine kinase inhibitor, erbstatin A, significantly reduced the formation of mixed platelet/PMN conjugates (Fig 2B). In contrast, the broad-based serine threonine protein kinases A, C, and G inhibitor H-7 and the specific MEK inhibitor PD98059 did not significantly modify adhesion (not shown). This confirms that protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN is specifically involved in enabling platelet/PMN firm adhesion.

Protein-tyrosine phosphorylation is required for platelet/PMN adhesion. (A) PMN were preincubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with different concentrations of genistein or an equivalent amount of DMSO before addition of PFA-fixed thrombin-activated platelets. In parallel, HE-loaded PMN were preincubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with different concentrations of genistein or an equivalent amount of DMSO before addition of PFA-fixed BCECF-loaded thrombin-activated platelets. Coincubation in standard conditions was stopped at 2 minutes and samples processed for the evaluation of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation and cell-cell adhesion. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative experiment, and the graph reports the optical density of the tyrosine-phosphorylated P∼110 in parallel with the number of platelets bound by 100 PMN. Values, reported as percentage of control, are means ± SEM, n = 3. (B) HE-loaded PMN were preincubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with erbstatin A (10 μg/mL; black triangles), genistein (10 μg/mL; black squares), or DMSO (control; white squares) before addition of PFA-fixed BCECF-loaded thrombin-activated platelets and incubation in standard conditions. The reaction was stopped at different times and samples processed for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Data report PLT/100 PMN and are expressed as percentage of the peak level (at 1 minute) of the DMSO-treated samples. At this time, 65 ± 8% of PMN bound 361 ± 150 platelets (means ± SEM, n = 3).

Protein-tyrosine phosphorylation is required for platelet/PMN adhesion. (A) PMN were preincubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with different concentrations of genistein or an equivalent amount of DMSO before addition of PFA-fixed thrombin-activated platelets. In parallel, HE-loaded PMN were preincubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with different concentrations of genistein or an equivalent amount of DMSO before addition of PFA-fixed BCECF-loaded thrombin-activated platelets. Coincubation in standard conditions was stopped at 2 minutes and samples processed for the evaluation of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation and cell-cell adhesion. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative experiment, and the graph reports the optical density of the tyrosine-phosphorylated P∼110 in parallel with the number of platelets bound by 100 PMN. Values, reported as percentage of control, are means ± SEM, n = 3. (B) HE-loaded PMN were preincubated for 2 minutes at 37°C with erbstatin A (10 μg/mL; black triangles), genistein (10 μg/mL; black squares), or DMSO (control; white squares) before addition of PFA-fixed BCECF-loaded thrombin-activated platelets and incubation in standard conditions. The reaction was stopped at different times and samples processed for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. Data report PLT/100 PMN and are expressed as percentage of the peak level (at 1 minute) of the DMSO-treated samples. At this time, 65 ± 8% of PMN bound 361 ± 150 platelets (means ± SEM, n = 3).

The functional availability of both P-selectin and CD11b/CD18 is required for platelet-induced tyrosine phosphorylation P∼110 in PMN.

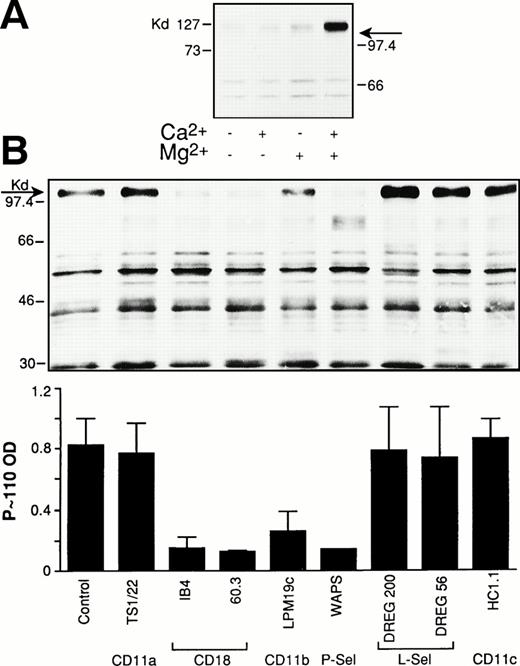

Platelet/PMN adhesion in stirred mixed-cell population requires P-selectin and CD11b/CD18.1 To investigate the role of these adhesive molecules in the platelet-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN, we first investigated the ion requirement for this phenomenon. As shown in Fig 3A, platelet-induced P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN could only be observed when both Ca2+ and Mg2+ were present, suggesting that, as already observed for adhesion, the functional integrity of both P-selectin and the β2-integrin is required for P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation to occur. This interpretation is furthermore supported by experiments in which P-selectin or the α or β chain of Mac-1 were blocked by specific MoAbs. Indeed, anti–P-selectin, anti-CD18, and anti-CD11b antibodies strongly reduced activated platelet-induced P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN (Fig 3B). Anti-CD11b/CD18 antibodies that did not inhibit adhesion did not modify P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation (not shown).

P-selectin and CD11b/CD18 are both required for platelet-induced protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. (A) PMN were coincubated with thrombin-activated platelets in standard conditions in the absence or in the presence of 1 mmol/L Ca2+ and Mg2+ alone or together. The reaction was stopped at 2 minutes and samples processed for protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative of two different experiments. (B) PMN and thrombin-activated platelets were preincubated for 15 minutes with the corresponding antibodies. Mixed-cell suspensions were coincubated in standard conditions, the reaction stopped at 2 minutes, and samples processed for analysis of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative experiment and bars report the optical density of the tyrosine-phosphorylated P∼110. Values are means ± SEM, n = 3 or 4.

P-selectin and CD11b/CD18 are both required for platelet-induced protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. (A) PMN were coincubated with thrombin-activated platelets in standard conditions in the absence or in the presence of 1 mmol/L Ca2+ and Mg2+ alone or together. The reaction was stopped at 2 minutes and samples processed for protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative of two different experiments. (B) PMN and thrombin-activated platelets were preincubated for 15 minutes with the corresponding antibodies. Mixed-cell suspensions were coincubated in standard conditions, the reaction stopped at 2 minutes, and samples processed for analysis of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. The figure shows the Western blot of samples from a representative experiment and bars report the optical density of the tyrosine-phosphorylated P∼110. Values are means ± SEM, n = 3 or 4.

To completely exclude any possible effect of additional molecules coexpressed with P-selectin on the surface of activated platelets, first the latter were substituted with CHO cells transfected with P-selectin encoding cDNA and second PMN were challenged with soluble, recombinant P-selectin–IgG chimera.

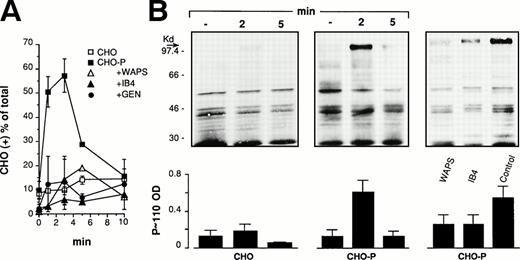

P-selectin expressed on CHO cells triggers genistein-sensitive β2-integrin–dependent adhesion and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation.

In initial experiments we evaluated PMN adhesion to wild-type (CHO) or P-selectin–expressing CHO cells (CHO-P) in suspensions (PMN:CHO ratio 5:1) at 37°C and 1,000 rpm stirring. As shown in Fig 4A, CHO-P cells transiently adhered to PMN forming mixed-cell conjugates that were strongly reduced, as expected, by an anti–P-selectin antibody. Moreover, PMN adhesion to CHO-P was also inhibited by an anti-CD18 antibody as well as by genistein, indicating, in agreement with previous observations,48 that CHO-P cells express in addition to P-selectin a β2-integrin ligand. Experiments in which wild-type CHO cells were incubated with PMN in the presence of Mn2+ in a Ca2+- and Mg2+-free medium showed that under this condition, PMN were able to form mixed conjugates with CHO cells that could be inhibited by different anti-CD18 as well by the anti-CD11b antibody LPM19c (not shown). This indicates that Mac-1 recognizes a ligand constitutively expressed on CHO cells. In the absence of exogenous activation, binding of this ligand by the β2-integrin requires coexpression of P-selectin and an intact tyrosin kinase(s) activity in PMN. Taken together these results indicate that to firmly adhere to P-selectin–expressing CHO cells in suspension at high shear rate, PMN use an adhesive machinery similar to that mediating adhesion to activated platelets. Similarly to what was observed with platelets, CHO-P/PMN adhesion was accompanied by the induction of P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig 4B).

P-selectin expressed on CHO cells triggers genistein-sensitive β2-integrin–dependent adhesion and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. (A) HE-loaded wild-type CHO or P-selectin expressing CHO (CHO-P) cells were incubated in suspension with PMN at a final ratio of 1:5 in standard conditions. The anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) was preincubated with PMN and the anti–P-selectin antibody (WAPS12.2) was preincubated with CHO-P for 15 minutes. PMN were pretreated with genistein (10 μg/mL; GEN) as in Fig2. The interaction was stopped at different times and samples processed for FACS analysis. Data report the percentage of CHO cells binding PMN. Values are means ± SEM, n = 3 to 5. (B) PMN and CHO-P were coincubated as reported above. The interaction was stopped at the indicated times or at 2 minutes, when the effect of antibodies was investigated. The figure shows the Western blot from a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (means ± SEM, n = 3).

P-selectin expressed on CHO cells triggers genistein-sensitive β2-integrin–dependent adhesion and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN. (A) HE-loaded wild-type CHO or P-selectin expressing CHO (CHO-P) cells were incubated in suspension with PMN at a final ratio of 1:5 in standard conditions. The anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) was preincubated with PMN and the anti–P-selectin antibody (WAPS12.2) was preincubated with CHO-P for 15 minutes. PMN were pretreated with genistein (10 μg/mL; GEN) as in Fig2. The interaction was stopped at different times and samples processed for FACS analysis. Data report the percentage of CHO cells binding PMN. Values are means ± SEM, n = 3 to 5. (B) PMN and CHO-P were coincubated as reported above. The interaction was stopped at the indicated times or at 2 minutes, when the effect of antibodies was investigated. The figure shows the Western blot from a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (means ± SEM, n = 3).

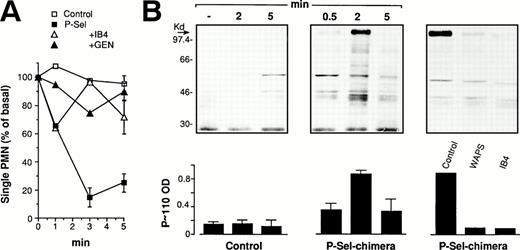

P-selectin–IgG fusion protein triggers genistein-sensitive β2-integrin–dependent homologous PMN aggregation and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation.

PMN aggregation represents homologous cell-cell adhesion, which is essentially mediated by the β2-integrin Mac-1.46 47 For this reason PMN aggregation can be considered a specific index of the functional upregulation of this integrin. Accordingly, in this study we decided to evaluate the effect of soluble P-selectin–IgG chimera on PMN aggregation as a functional index of the ability of soluble P-selectin to trigger the activation of Mac-1. As reported in Fig 5A, P-selectin chimeras induced PMN aggregation, which was prevented by the anti-CD18 antibody. Moreover, according to the inhibition of platelet/PMN or CHO-P/PMN aggregation, P-selectin–induced PMN/PMN aggregation was also blocked by genistein, reinforcing the hypothesis of an important regulatory role for protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in P-selectin–triggered Mac-1 function. The P-selectin–IgG chimera was also able to induce a strong tyrosine phosphorylation of P∼110 protein (Fig 5B).

P-selectin–IgG chimera triggers genistein-sensitive, β2-integrin–dependent PMN aggregation and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) PMN were incubated in standard conditions in the presence of 50 μg/mL of nonimmune human IgG in the absence (control) or in the presence of 10 μg/mL of P-selectin–IgG chimera (P-sel). PMN were preincubated with the anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) or with genistein (GEN) as reported in Figs 2 and 3. The reaction was stopped, and PMN remaining single, nonaggregated were counted by optical microscopy in a Burker chamber. Values (means ± SEM, n = 3 or 4) are reported as percentage of the basal level. (B) PMN were challenged with P-selectin–IgG chimera as reported above. The reaction was stopped at different times. The figure shows the Western blot from a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (mean ± SEM, n = 2 or 3).

P-selectin–IgG chimera triggers genistein-sensitive, β2-integrin–dependent PMN aggregation and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) PMN were incubated in standard conditions in the presence of 50 μg/mL of nonimmune human IgG in the absence (control) or in the presence of 10 μg/mL of P-selectin–IgG chimera (P-sel). PMN were preincubated with the anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) or with genistein (GEN) as reported in Figs 2 and 3. The reaction was stopped, and PMN remaining single, nonaggregated were counted by optical microscopy in a Burker chamber. Values (means ± SEM, n = 3 or 4) are reported as percentage of the basal level. (B) PMN were challenged with P-selectin–IgG chimera as reported above. The reaction was stopped at different times. The figure shows the Western blot from a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (mean ± SEM, n = 2 or 3).

These results together with those obtained with CHO-P cells show that P-selectin interaction with its receptor(s) on PMN is sufficient to switch on the tyrosine phosphorylation–dependent signal that upregulates the β2-integrin function.

Engagement of the β2-integrin with the ligand is required for P-selectin–triggered P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN.

Similar to what was already observed with activated platelets, triggering of P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation by CHO-P cells or by P-selectin–IgG chimera required the functional availability of the β2-integrin. Indeed, as reported in Fig 4B, the adhesion-blocking anti-CD18 antibody IB4 blocked CHO-P–induced P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation. Similar results were obtained when PMN were challenged with recombinant P-selectin. P-selectin–triggered P∼110 tyrosine phosphorylation was abolished by the aggregation blocking anti-CD18 antibodies IB4 (Fig 5B) and 60.3.

PSGL-1 triggers tyrosine phosphorylation–dependent CD11b/CD18 adhesion.

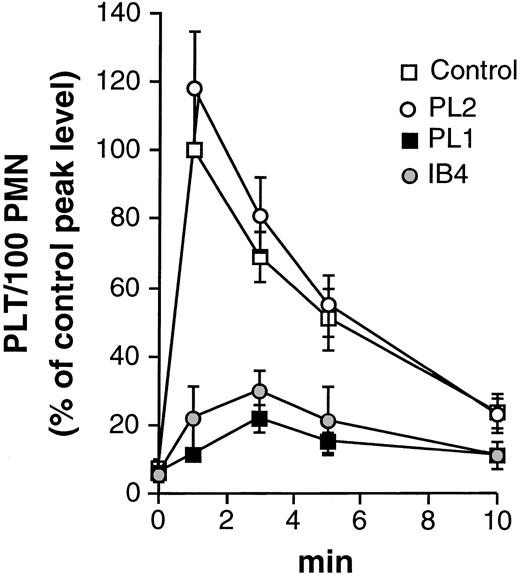

The role of PSGL-1 as major P-selectin receptor on PMN was first investigated by evaluating the effect of anti–PSGL-1 MoAbs on activated platelet/PMN adhesion. As reported in Fig 6, blockade of PSGL-1 with the inhibitory antibody PL1 strongly reduced the formation of mixed-cell conjugates, indicating a major role of PSGL-1 as P-selectin ligand in our system.

PSGL-1 mediates activated platelet/PMN adhesion. HE-loaded PMN were preincubated for 15 minutes at 4°C in the absence (control) or in the presence of the noninhibitory (PL2), the inhibitory (PL1) anti–PSGL-1, or with the anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) before addition of PFA-fixed BCECF-loaded thrombin-activated platelets. Data report the number of platelets bound by 100 PMN (PLT/100 PMN) and are expressed as percentage of the peak level (at 1 minute) of the untreated sample. At this time, 65.7 ± 5.3% of PMN bound 393 ± 55 platelets (means ± SEM, n = 2 to 5).

PSGL-1 mediates activated platelet/PMN adhesion. HE-loaded PMN were preincubated for 15 minutes at 4°C in the absence (control) or in the presence of the noninhibitory (PL2), the inhibitory (PL1) anti–PSGL-1, or with the anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) before addition of PFA-fixed BCECF-loaded thrombin-activated platelets. Data report the number of platelets bound by 100 PMN (PLT/100 PMN) and are expressed as percentage of the peak level (at 1 minute) of the untreated sample. At this time, 65.7 ± 5.3% of PMN bound 393 ± 55 platelets (means ± SEM, n = 2 to 5).

Because it was recently reported that engagement of PSGL-1 by MoAb is able to stimulate protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in PMN,32 we investigated whether the effects of P-selectin on PMN could be reproduced by PSGL-1 engagement with specific MoAbs. As reported in Fig 7A, incubation of PMN with the noninhibitory anti–PSGL-1 antibody PL2 induced PMN aggregation. This effect was more pronounced when PL2 was crosslinked with a secondary anti-mouse F(ab)2 fragment. PMN aggregation induced by PL2 cross-linking was inhibited by the anti-CD18 antibody IB4 and by genistein, indicating that engagement of PSGL-1 enables a tyrosine kinase(s)–dependent β2-integrin–mediated homologous adhesion. Furthermore, in agreement with previous data,32 we also found that ligation of PSGL-1 with PL1 or PL2 alone resulted in increased tyrosine phosphorylation of different proteins, as well in the appearance of a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of about 110 kD. This effect was potentiated after cross-linking (Fig 7B). Taken together these results indicate that PSGL-1 represents not only the tethering molecule linking PMN to P-selectin–expressing cells, but it also triggers the tyrosine phosphorylation–dependent signal upregulating the adhesive function of Mac-1.

Engagement of PSGL-1 by the monoclonal antibody PL2 triggers genistein-sensitive, β2-integrin–dependent PMN aggregation and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) PMN were preincubated at 4°C with PL2 (anti-PSGL-1), rapidly washed to remove unbound antibody, and incubated in the absence [PL2-F(ab)2] or in the presence [PL2+F(ab)2] of 10 μg/mL of rabbit anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2 fragments in standard conditions. The anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) was preincubated with PMN together with PL2 for 15 minutes at 4°C before cross-linking. PMN were treated with genistein (10 μg/mL; GEN) for 1 minute after preincubation with PL2 and before cross-linking. In control experiments, PMN were preincubated at 4°C with HC1.1 (anti-CD11c), washed to remove unbound antibody, and incubated in the presence of 10 μg/mL of anti-mouse F(ab)2 fragments in standard conditions [HC1.1+F(ab)2]. PMN aggregation was evaluated as in Fig6. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). (B) PMN were treated and incubated exactly as for aggregation experiments. The figure shows the Western blot of a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (means ± SEM, n = 2 to 3).

Engagement of PSGL-1 by the monoclonal antibody PL2 triggers genistein-sensitive, β2-integrin–dependent PMN aggregation and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) PMN were preincubated at 4°C with PL2 (anti-PSGL-1), rapidly washed to remove unbound antibody, and incubated in the absence [PL2-F(ab)2] or in the presence [PL2+F(ab)2] of 10 μg/mL of rabbit anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2 fragments in standard conditions. The anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) was preincubated with PMN together with PL2 for 15 minutes at 4°C before cross-linking. PMN were treated with genistein (10 μg/mL; GEN) for 1 minute after preincubation with PL2 and before cross-linking. In control experiments, PMN were preincubated at 4°C with HC1.1 (anti-CD11c), washed to remove unbound antibody, and incubated in the presence of 10 μg/mL of anti-mouse F(ab)2 fragments in standard conditions [HC1.1+F(ab)2]. PMN aggregation was evaluated as in Fig6. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). (B) PMN were treated and incubated exactly as for aggregation experiments. The figure shows the Western blot of a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (means ± SEM, n = 2 to 3).

DISCUSSION

Like endothelial cells,2 platelet monolayers10-14 or platelets aggregated in a growing thrombus 15,16 sustain accumulation of flowing PMN. This suggests that activated platelets express the complete adhesive and signaling machinery necessary for the multistep adhesion cascade essential for PMN recruitment under shear conditions. This adhesive machinery is initiated by P-selectin–dependent attachment and rolling of PMN. The velocity of rolling PMN rapidly slows down, and they arrest within few seconds after initial tethering on the platelet surface.13 Arrest of rolling PMN can be blocked by anti-CD11b/CD18 antibodies, indicating that it is based on the binding of this molecule to a counter-receptor on platelets.13,14At variance with P-selectin binding to its counter-receptor, the β2-integrin CD11b/CD18 is not constitutively able to recognize the ligand but requires functional upregulation.49,50 The requirement for a platelet-induced activation of PMN arrest on a platelet monolayer was first suggested by Yeo et al.10 In a recent study,1 we confirmed and extended this concept showing that activated platelet/PMN adhesion in mixed-cell suspensions subjected to high shear rate can be modeled as a two-step adhesion cascade requiring P-selectin and the β2-integrin CD11b/CD18. In this model, platelet/PMN mixed conjugates did not form in the presence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, suggesting a functional cross talk between P-selectin receptor and the β2-integrin that involves protein-tyrosine phosphorylation.

These observations opened the question whether P-selectin is directly or indirectly involved in the mechanisms allowing activated platelets to stimulate the tyrosine kinase(s)–dependent adhesive function of Mac-1.

In the present study, we showed for the first time that binding of activated platelets to PMN triggers protein-tyrosine phosphorylation, particularly that of a major protein of about 110 kD. This shows that activated platelets stimulate intracellular signal(s) able to activate tyrosine kinase(s) in PMN. Moreover, the dose-dependent inhibition of the tyrosine phosphorylation of this protein by genistein correlates with its ability to inhibit platelet/PMN adhesion, supporting a functional relationship between these two events. The effect of activated platelets could be mimicked by P-selectin either expressed on transfected cells or in solution. In fact, P-selectin either expressed on CHO cells or as soluble recombinant P-selectin–IgG chimera were able to trigger the tyrosine kinase(s)–dependent adhesive function of the β2-integrin. Binding of PMN to P-selectin transfected CHO cells as well as PMN/PMN aggregation were both mediated by the β2-integrin Mac-1 and ligands expressed on CHO cells or PMN. PMN adhesion to CHO-P as well as stimulation of PMN by soluble P-selectin–IgG chimera resulted in tyrosine phosphorylation of a protein with molecular mass of about 110 kD.

An important role in transmitting the P-selectin–induced signal is probably played by PSGL-1. In fact, an inhibitory anti PSGL-1 monoclonal antibody strongly reduced platelet/PMN adhesion, indicating that PSGL-1 is the most important receptor tethering activated platelets to PMN in our system. Moreover, the engagement of PSGL-1 with a noninhibitory MoAb resulted in a β2-integrin–, tyrosine kinase(s)–dependent homologous PMN aggregation. This shows that PSGL-1 engagement triggers functional upregulation of Mac-1. Moreover, in agreement with Hidari et al,32 we also observed that engagement of PSGL-1 by specific MoAbs increased protein phosphorylation of different proteins in PMN. Altogether the results of our experiments argue in favor of the interpretation that the binding of P-selectin to PSGL-1 on PMN is able to transmit signals able to activate the β2-integrin Mac-1. However, this interpretation does not exclude that additional molecules, acting in a juxtacrine fashion and requiring engagement of PSGL-1, could still be playing an important role during platelet-PMN and PMN-PMN interaction.51 The latter interpretation is also in agreement with data from Lorant et al52 showing that P-selectin enhances β2-integrin activation by other agonists.

P∼110 is the major protein undergoing tyrosine phosphorylation during cell-cell interaction in our model, suggesting that this protein could play a role in regulating the β2-integrin adhesiveness. This would imply that first an initial weak interaction of the integrin with its ligand allows tyrosine phosphorylation of P∼110 and that this, in turn, would be necessary for the β2-integrin to acquire the full adhesive phenotype. Indeed, in agreement with previous studies,53, 54 we found that antibody-mediated cross-linking of the β2 chain results in tyrosine phosphorylation of different proteins, including P ∼ 110 (data not shown). In this scenario, P-selectin interacting with its receptor on PMN may directly trigger the initial integrin ligand interaction and/or it may contribute to the activation and recruitment of tyrosine kinase(s) necessary for phosphorylation of key protein(s), possibly P∼110.

To clarify the identity of this protein requires further work and will allow the role of protein-tyrosine phosphorylation in β2-integrin function to be elucidated.

The P-selectin–Mac-1 cross-talk, regulated by protein-tyrosine phosphorylation, that clearly emerges from our study may also occur when PMN interact with activated endothelial cells via P-or E-selectin in flow conditions.

Knowledge of the mechanisms and molecules that regulate these phenomena may help design drugs for novel anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic pharmacological intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Paolo Pertile for fruitful discussion; Drs E.C. Butcher, C.G. Gahmberg, K.L. Moore, R.P. McEver, J. Harlan, J.L. McGregor, N. Hogg, K. Pulford, and C. Bernabeu for their kind gift of antibodies; Dr B. Furie and the Genetics Institute of Cambridge, MA, for kindly providing P-selectin–transfected CHO cells; and the Art Department and the Gustavus A. Pfeiffer Memorial Library staffs for their contribution in editing the figures and the manuscript.

Supported by the Italian National Research Council (Convenzione CNR—Consorzio Mario Negri Sud and “Altri interventi 1998”) and by the Fondation Segré, Geneva, Switzerland.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Virgilio Evangelista, MD, Unit of Biology of Cell Interactions, Consorzio “Mario Negri Sud,” Via Nazionale, 66030 Santa Maria Imbaro, Italy; e-mail: evangeli@CMNS.MNEGRI.IT.

![Fig. 7. Engagement of PSGL-1 by the monoclonal antibody PL2 triggers genistein-sensitive, β2-integrin–dependent PMN aggregation and stimulates protein-tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) PMN were preincubated at 4°C with PL2 (anti-PSGL-1), rapidly washed to remove unbound antibody, and incubated in the absence [PL2-F(ab)2] or in the presence [PL2+F(ab)2] of 10 μg/mL of rabbit anti-mouse IgG F(ab)2 fragments in standard conditions. The anti-CD18 antibody (IB4) was preincubated with PMN together with PL2 for 15 minutes at 4°C before cross-linking. PMN were treated with genistein (10 μg/mL; GEN) for 1 minute after preincubation with PL2 and before cross-linking. In control experiments, PMN were preincubated at 4°C with HC1.1 (anti-CD11c), washed to remove unbound antibody, and incubated in the presence of 10 μg/mL of anti-mouse F(ab)2 fragments in standard conditions [HC1.1+F(ab)2]. PMN aggregation was evaluated as in Fig6. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). (B) PMN were treated and incubated exactly as for aggregation experiments. The figure shows the Western blot of a representative of three different experiments and the corresponding optical density of P∼110 (means ± SEM, n = 2 to 3).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/3/10.1182_blood.v93.3.876/5/m_blod40325007w.jpeg?Expires=1769228631&Signature=PzsB9WRyPA2klcpatq5BD73PJUPuvygs99G1krDt6shZTdJHUlJpzM0KHsqDvejRHkW9cjQD8Oq-lCGhkCQ2R3AcDKPJmaxjLL1Nvy2SNMc7YHFwj1Bmech8bHIbPtrPtUer4ZD-1gGenrvCkYUxAQHEmW1EbeOkhnLKGWJtwUXtkxFD~34nPm9Xw9nHZmecjuwaU3B7tDGWkJPPvXrPJic0tB3kRb9wAg3HY9fCNh3eE4S767wkWbMmHKmn5ehFQ8qgHB4cMuq4a-xYlBqbXmRMjEbEZCmNxp6IZ7TKM4-P38ONCqIhblLMlYssOfVI87Jw5n0ayZliKA2pJickZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)