Abstract

Integrin-mediated adhesion influences cell survival and may prevent programmed cell death. Little is known about how drug-sensitive tumor cell lines survive initial exposures to cytotoxic drugs and eventually select for drug-resistant populations. Factors that allow for cell survival following acute cytotoxic drug exposure may differ from drug resistance mechanisms selected for by chronic drug exposure. We show here that drug-sensitive 8226 human myeloma cells, demonstrated to express both VLA-4 (4β1) and VLA-5 (5β1) integrin fibronectin (FN) receptors, are relatively resistant to the apoptotic effects of doxorubicin and melphalan when pre-adhered to FN and compared with cells grown in suspension. This cell adhesion mediated drug resistance, or CAM-DR, was not due to reduced drug accumulation or upregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members. As determined by flow cytometry, myeloma cell lines selected for drug resistance, with either doxorubicin or melphalan, overexpress VLA-4. Functional assays revealed a significant increase in 4-mediated cell adhesion in both drug-resistant variants compared with the drug-sensitive parent line. When removed from selection pressure, drug-resistant cell lines reverted to a drug sensitive and 4-low phenotype. Whether VLA-4–mediated FN adhesion offers a survival advantage over VLA-5–mediated adhesion remains to be determined. In conclusion, we have demonstrated that FN-mediated adhesion confers a survival advantage for myeloma cells acutely exposed to cytotoxic drugs by inhibiting drug-induced apoptosis. This finding may explain how some cells survive initial drug exposure and eventually express classical mechanisms of drug resistance such as MDR1 overexpression.

MULTIPLE MYELOMA is an incurable malignancy of the plasma cell characterized by migration and localization to the bone marrow where cells then disseminate and facilitate the formation of bone lesions. Despite initial responses to chemotherapy, myeloma patients ultimately develop drug resistance and become unresponsive to a wide spectrum of anti-cancer agents, a phenomenon known as multidrug resistance (MDR). The development of resistance to front-line chemotherapeutic drugs, such as melphalan (an alkylating agent) and doxorubicin (an anthracycline), is a major factor responsible for treatment failure. P-glycoprotein–mediated drug resistance has been well characterized in hematologic malignancies1 2; however, this mechanism alone cannot account for all drug resistance found in vivo or in vitro, nor is it likely to explain cell survival following initial cytotoxic drug exposure. Non–P-glycoprotein mechanisms conferring low level drug resistance are believed to play important roles in the survival and expansion of the malignant cell population. Factors that allow for tumor cell survival following initial drug exposure need to be identified because these factors may eventually allow for expression of genes associated with acquired drug resistance. For this reason, we investigated the role of a novel, cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) mechanism that suppresses drug-induced apoptosis and may allow for the eventual emergence of other well characterized mediators of drug resistance such as P-glycoprotein.

It has long been known that intercellular interactions may contribute to tumor cell survival during exposure to cytotoxic stresses such as radiation, as was first described by Durand and Sutherland.3 It is also well documented that certain resistance mechanisms may only be functional in vivo, where tumor cells continue to interact with environmental factors such as extracellular matrix (ECM) and cellular counter-receptors. Teicher et al showed that mammary tumors made resistant to alkylating agents in vivo were sensitized to cytotoxic drugs once removed from the animal.4 Most mechanisms of drug resistance that have been discovered were examined in vitro where tumor cell-environmental interactions are not fully appreciated. Within the last 5 years, it has been realized that cell–cell or cell–ECM adhesion can regulate apoptosis and cell survival in a wide variety of cell types.5-7 Adhesive interactions between same cell types have been shown to confer resistance to alkylating agents via alterations in cyclin dependant kinase inhibitors such as p27kip1 although the cell surface molecules mediating this type of kinetic resistance have yet to be identified.8 In addition, adhesion to ECM has been reported to induce P-glycoprotein expression and confer doxorubicin resistance in rat hepatocytes.9

The integrin family of cellular adhesion molecules is a major class of receptors through which cells interact with extracellular matrix components (ECM) and recent evidence has implicated the integrins as being closely involved in the pathology of many diseases.10-12 Integrins have been shown to participate in intracellular signal transduction pathways that may contribute to tumor cell growth and survival, although many of their functions have yet to be characterized in myeloma. Experimental evidence has implicated the β1 integrins and FN as playing a part in apoptotic suppression and cell survival.13-16 Zhang et al14 demonstrated that FN adhesion through α5β1 (VLA-5) prevented cells from undergoing serum-starvation induced apoptosis by upregulating Bcl-2. Similar observations were made by Scott et al15 and Rozzo et al,16 who found that anti-β1 antibodies and antisense oligonucleotides, respectively, enhanced chromatin condensation and nucleosomal DNA laddering, characteristics of cells committed to apoptosis. β1 integrin activation through interactions with ECM components such as FN has also been shown to directly decrease DNA strand breaks in tumor-derived endothelial cells exposed to a number of DNA damaging agents, including etoposide and ionizing radiation.17,18 The α4β1 (Very Late Activation Antigen 4, or VLA-4), α5β1(VLA-5), and α4β7 heterodimers are the major FN receptors of the integrin family.12,19 Although VLA-5 and α4β7 expression seem to be variable in most B cells during malignancy, VLA-4 is strongly expressed in myeloma cells collected from bone marrow.20,21 VLA-4 is unique among the integrins as it is the only heterodimer to have conclusively been shown to mediate cell-ECM as well as cell–cell interactions.22 VLA-4 binds to the CS-1 region of FN as well as to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) via separate binding sites.23 Adhesion to FN via VLA-4 has been shown to prolong eosinophil survival and to downregulate FAS antigen expression, leading to a decrease in cell death.24,13 In early hematopoietic and germinal center B cells, adhesion to FN or VCAM-1 via VLA-4 suppresses the apoptotic pathway and contributes to positive selection, an observation that may have relevance to apoptosis-inducing DNA damaging agents targeted at malignant B cells.25,26Whether any of these adhesion-related resistance mechanisms play a role in myeloma cell survival has yet to be demonstrated; however, longer survival times were obtained when mice injected with a number of tumors, including B lymphoma cells, were treated with a combination of anti–FN-adhesion agents and anticancer drugs.27

As myeloma cells adhere in the bone marrow, they stimulate their own growth and cause osteoclast formation through the increased synthesis and secretion of cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-β, M-CSF, and IL-6.28,29 IL-6, a potent growth factor for myeloma cells, is secreted from both tumor and stromal cells in response to co-adhesion and VLA-4 ligation.30 VLA-4 has recently been shown to associate with or cause the phosphorylation of a number of signal transduction molecules including CD19 receptor-associated protein tyrosine kinases and focal adhesion kinase (pp125FAK, or FAK), which is an upstream activator of mitogen activated protien kinase (MAPK), among other proteins.31-34 FAK is now known to play a major role in suppressing apoptosis both in adherent and suspension cells, and its cleavage by caspases early in the apoptotic process further emphasizes its importance within the cell.35-37 Given the evidence that FN adhesion and integrin engagement enhances cell survival in many cases, we examined the relationship between expression and function of the major integrin fibronectin receptors and response to cytotoxic drugs in the human myeloma derived cell line RPMI 8226. Drug-resistant variants were used to examine changes in integrin expression and function following chronic drug exposure, while the drug-sensitive parent line was used to assess the effects of FN on acute drug response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell and culture conditions.

The RPMI 8226 human myeloma cell line (8226/S) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The drug resistant cell lines, 8226/DOX6 and 8226/LR5, were selected from 8226/S using step-wise increases of doxorubicin and melphalan, respectively, as described previously.38 39 All cells were grown in suspension in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine-serum, 1% (vol/vol) penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 U/mL), and 1% (vol/vol) L-glutamine (all from GIBCO-BRL, Grand Island, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2-95% air atmosphere and subcultured every 6 days.

Drugs.

Melphalan (L-phenylalanine nitrogen mustard, LPAM) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) and was dissolved in acidified ethanol. Doxorubicin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in sterile ddH2O.

Cytotoxicity assays.

96-Well immunosorp plates (Nunc, Denmark) were coated with 50 μL (40 μg/mL) FN (GIBCO) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) overnight and 1% BSA was used to block nonspecific binding sites in the wells for 1 hour before the experiment. Wells were washed with serum-free RPMI 1640 and aspirated. 8226/S cells were washed once and resuspended in serum-free RPMI 1640; then 4 × 104 cells per well (FN coated) or 8 × 103 cells per well (BSA coated) were added to each plate. Cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C and 5% CO2, washed with serum free media twice, and were put back into serum-containing media. Following 24 hours in a tissue culture incubator, 20 μL of diluted drug or vehicle control was added to each well for 1 hour, after which media was removed and replaced by drug-free media. Following a 96-hour incubation, 50 μL MTT dye (Sigma) was added to each well for 4 hours. Plates were then centrifuged and each well aspirated. Dye was solubilized with 100 μL DMSO and plates were read at 540 nm on an automated microtiter plate reader. A blank well containing only media and drug was also run as a control in all experiments. IC50 values were calculated by linear regression of percent survival versus drug concentration.

Annexin V apoptotic analysis.

Cells, 1 × 106, were attached to FN-coated 6-well plates (Biosource, Camarillo, CA) for 1 hour in serum-free media and nonadhered cells were removed with two washes. Fresh media with serum was added to the plates, which were incubated for 24 hours; 1 × 106 cells were also added to uncoated 6-well plates (Boeringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were exposed to 1 μmol/L doxorubcin for 1 hour (plus a 24-hour drug-free incubation period) or 50 μmol/L LPAM for 24 hours. Cells were then collected with 5 mmol/L EDTA/PBS and washed. Phycoerythrin (PE)- or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Annexin V (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was then added to 1 × 105 cells and 5,000 to 10,000 events were analyzed on a FACScan machine (Becton Dickinson).

RNA collection and cDNA synthesis from FN-adhered myeloma cells.

Cells, 1 × 106, were attached to FN coated 6-well plates as previously described. Total cellular RNA was collected on 3 separate days using TRIzol reagent (GIBCO). RNA was quantitated on a spectophotometer at 260 nm and 1 μg was DNAse treated and requantitated. A single large scale cDNA reaction was prepared for each sample for use in PCR reactions. A 40 μL reverse transcription reaction containing 200 ng RNA, 1 × PCR buffer (10 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.3–50 mmol/L MKCL-1.5 mmol/L MgCl2), 1 mmol/L concentrations each of dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP; 200 pmol random hexamers, 40 U RNAse inhibitor, and 12 U avian megalovirus reverse transcriptase (Boeringer-Mannheim) was prepared on ice then incubated at 42°C for 1 hour, 99°C for 10 minutes, and quick chilled to 4°C.

RNase protection assay.

Twenty micrograms of RNA was isolated from 8226/S cells grown in suspension or adhered to FN using TRIzol reagent and resuspended in hybridization buffer. Bcl-2 family specific probes were synthesized using a template set from Riboquant (San Diego, CA) and labeled using [α-32P]UTP and T7 polymerase. Probes were then column purified, quantitated on a scintillation counter, and 5 × 105 cmp was added to each sample. The hybridization reaction was carried out overnight at 56°C. Samples were then RNase treated for 45 minutes at 30°C, hybridized probes were extracted with chloroform:isoamyl alcohol and precipitated using 100% ethanol. Samples were then electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (7 mmol/L Urea), dried down, exposed to film, and analyzed by densitometry software (ImageQuaNT, Molecular Dynamics, Inc, Sunnyvale, CA). Unhybridized probes were used as size standards for each gene analyzed. Expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-Xl, Bcl-Xs, BAX, Bik, Bad, Bcl-w, Bak, Mcl-1, and Bfl1 were quantitated by normalizing to GAPDH and L32 expression.

RT-PCR analysis of BCL-2 family gene and drug transporter expression.

BCL-2 amplification was performed essentially as described previously.40 Briefly, 20 μL of PCR reaction mixture (1X PCR buffer, 50 pmol of BCL-2 specific amplimers, 0.25 U Taq polymerase [Boehringer-Mannheim], 1.25 μci [α-32P]-dCTP) was added to 5 μL cDNA, followed by incubation at 94°C for 5 minutes and then 26 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 72°C for 1 minute, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes in a thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). Histone 3.3 was amplified as described and used as a control for RNA integrity and quantity.41 Bcl-Xl and -Xs were amplified essentially as described previously, using 26 cycles of PCR.42 The 258 base pair BAX amplicon was amplified using the following primers (Biosynthesis, Lewisville, TX) and conditions: BAX-upstream (5′-ACCAAGAAGCTGAGCGAGTGTCTC-3′), BAX-downstream (5′-CAATGTCCAGCCCATGATGG-3′), cDNA denaturation for 1 minute at 94°C, annealing for 15 seconds at 60°C, primer extension for 15 seconds at 72°C, with a final extension for 5 minutes. All samples were loaded on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed for 2 hours at 80V. For determination of incorporated radionucleotide, gels were dried down and exposed to a phosphorimaging plate (Molecular Dynamics, Inc) overnight. Plates were then scanned on the STORM phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics) and band intensities (pixels/unit area) for Bcl-2, Bcl-Xl, Bcl-Xs, and BAX were analyzed using ImageQuaNT software and normalized to Histone 3.3 expression. PCR amplification of the MDR1, MRP, and LRP genes was performed essentially as described,41,43,44 using the housekeeping genes histone 3.3 (MDR1) or β-actin (MRP and LRP) as internal standards. cDNA synthesized from 8226/DOX6 RNA was used as a positive control for MDR1 PCR. For all reactions, optimal cycle numbers were used and were within the exponential range of PCR amplification as determined by previous experiments.41,43 44

Intracellular drug accumulation assay.

Cells, 0.5 × 106, were adhered to FN-coated 6-well plates for 24 hours, as described previously. Control wells were coated with BSA or were uncoated. RPMI 1640 containing doxorubicin was added to each treatment well for a final concentration of 10 μmol/L. After 1 hour at 37°C, cells were washed three times with cold PBS and analyzed for FL-2 flourescence on a FACScan machine. Ten-thousand events were recorded for each condition, which were performed in triplicate. Experiments were repeated twice.

Antibodies and phenotypic analysis of cell lines.

Cell surface integrin expression was determined using the monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) P4G9 (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) for CDw49d (α4) analysis, A1A5 for CD29 (β1) analysis (T Cell Diagnostics, Woburn, MA), P1D6 (DAKO) for CDw49e (α5) analysis, and FIB504 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for β7 analysis. Cells, 1 × 106, were incubated with primary antibody or an isotype control, then with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rat secondary antibody. Fluorescence was then analyzed by flow cytometry with a FACScan machine, which recorded 10,000 events for each experiment.

Adhesion assays.

Cells, 1.5 × 105, were adhered to FN- or BSA-coated well plates as described previously. After three washes to remove unattached cells, adherent cells were fixed in 70% methanol for 10 minutes. Following aspiration, wells were allowed to dry and then were stained with 0.02% crystal violet/.2% ethanol for an additional 10 minutes. After solubilization with 100 μL Sorenson buffer, absorbance at 540 nm was read with an automated microtiter plate reader. In some experiments, cells were pre-incubated for 15 minutes with P4G9 or HP2/1 (Clonetech, Palo Alto, CA) (anti–VLA-4), P1D6 (anti–VLA-5), or isotype antibody controls before application to wells.

RESULTS

FN-adhered myeloma cells show a decreased response to doxorubicin by MTT cytotoxicity analysis.

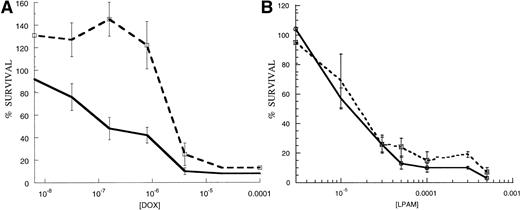

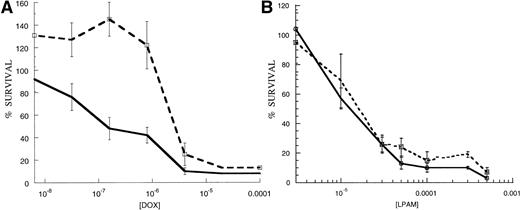

To assess whether or not engagement of cell surface integrins can contribute to cell survival, we used a short-term MTT-based cytotoxicity assay. 8226/S cells were adhered to FN-coated wells for 1 hour, and unbound cells were removed by aspiration and washes with serum-free media. As a control, an approximately equal cell number was added to uncoated wells or wells coated with BSA. After 24 hours, doxorubicin or melphalan was added to each well for 1 hour, drug-containing media was then removed and replaced by fresh media. After a 96-hour incubation, cell survival was determined by the ability of viable cells to reduce MTT dye to formazan. IC50 values were derived through linear regression of the log-linear dose-response plots for each cell line to each drug. Student’s t-test was used to analyze differences in drug response using data collected from three different experiments (.05 significance level). We found that 8226/S myeloma cells adhered to FN-coated plates have a significant survival advantage over those grown on BSA-coated plates when exposed to doxorubicin for 1 hour following a 24-hour pre-adhesion period (Fig1A), (n = 3, mean difference = 6.9, SD = 5.2, range = 2.4 to 12.6, P < .05). The mean IC50 value for FN-adhered cells was 1.63 μmol/L dox (SD = 1.51, range = 0.49 μmol/L to 3.34 μmol/L) compared with 0.52 μmol/L for cells grown on BSA (n = 3, SD = 0.76, range = 0.085 μmol/L to 1.4 μmol/L). Subtoxic concentrations of doxorubicin often induced a mitogenic effect in FN-adhered cells (>100% survival), an effect seen with other cell types45and in drug-resistant cells (our unpublished observations). FN-adhered cells often showed a decreased response to melphalan (Fig 1B); however, this effect proved to be inconsistent (n = 3, mean difference = 1.7, SD = 0.8, range = 1.2 to 2.6). The mean IC50 value for FN-adhered cells was 48 μmol/L melphalan (n = 3, SD = 26 μmol/L, range = 18 μmol/L to 65 μmol/L), compared with 30 μmol/L for cells grown on BSA (n = 3, SD = 20 μmol/L, range = 15 μmol/L to 53 μmol/L).

8226/S myeloma cells adhered to FN have a survival advantage over nonadhered cells following acute doxorubicin exposure (A) but not following melphalan exposure (B) in cell growth based cytotoxicity assays. FN-adhered cells (---) were bound to FN-coated plates 24 hours before 1-hour drug exposure and control cells were grown in suspension (—). Response to doxorubicin was 12.6-fold lower in FN-adhered cells compared to nonadhered controls (IC50 values for adhered and nonadhered cells were of 4.85 × 10−7 mol/L and 8.5 × 10−8 mol/L, respectively). Data points are presented as cell viability determined by MTT cytotoxicity assay compared with untreated controls. Graphs are representative experiments that were repeated three times in replicates of four.

8226/S myeloma cells adhered to FN have a survival advantage over nonadhered cells following acute doxorubicin exposure (A) but not following melphalan exposure (B) in cell growth based cytotoxicity assays. FN-adhered cells (---) were bound to FN-coated plates 24 hours before 1-hour drug exposure and control cells were grown in suspension (—). Response to doxorubicin was 12.6-fold lower in FN-adhered cells compared to nonadhered controls (IC50 values for adhered and nonadhered cells were of 4.85 × 10−7 mol/L and 8.5 × 10−8 mol/L, respectively). Data points are presented as cell viability determined by MTT cytotoxicity assay compared with untreated controls. Graphs are representative experiments that were repeated three times in replicates of four.

Annexin V flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis.

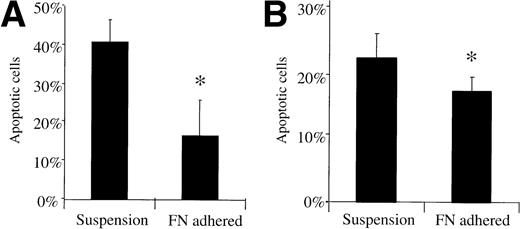

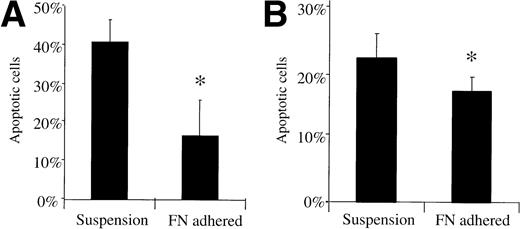

As a second marker for apoptosis not based on cell growth, we used PE- or FITC-conjugated Annexin V, which recognizes inverted phosphatidylserine on the exterior of the plasma membrane as an early stage apoptotic marker. Approximately 0.5 × 106 8226/S cells were adhered to FN-coated or uncoated 6-well tissue culture plates for 24 hours before being exposed to either 1 μmol/L doxorubicin or 50 μmol/L melphalan. After a 24-hour incubation, cells were collected and the apoptotic fraction determined using Annexin V staining and flow cytometric analysis. FN-adhered 8226/S cells had a lower percentage of apoptotic cells (mean = 16.3%) compared with nonadhered controls (mean = 40.3%) following a 1-hour doxorubicin exposure (P < .05) (Fig 2A). A smaller, but statistically different (P < .05), effect was seen with FN-adhered cells treated with 50 μmol/L melphalan (16.53%v 21.5%) (Fig 2B). In some experiments, cells were exposed to drug before FN-adhesion in an attempt to rescue them from the consequent initiation of apoptosis. Annexin V staining revealed that FN adhesion is unable to rescue myeloma cells following initial exposure to doxorubicin or melphalan (data not shown).

Annexin V stained FN-adhered myeloma cells have a lower apoptotic fraction compared to nonadhered cells following acute drug exposure. 8226/S myeloma cells were exposed to 1 μmol/L doxorubicin for 1 hour (A) or 50 μmol/L melphalan for 24 hours (B), stained by Annexin V 24 hours later, then analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms are adjusted for background staining in untreated cells, bars are the SD of three different experiments; ∗, P < .05.

Annexin V stained FN-adhered myeloma cells have a lower apoptotic fraction compared to nonadhered cells following acute drug exposure. 8226/S myeloma cells were exposed to 1 μmol/L doxorubicin for 1 hour (A) or 50 μmol/L melphalan for 24 hours (B), stained by Annexin V 24 hours later, then analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms are adjusted for background staining in untreated cells, bars are the SD of three different experiments; ∗, P < .05.

Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-XS, and BAX mRNA levels are unchanged in 8226/S following 24-hour adhesion to FN.

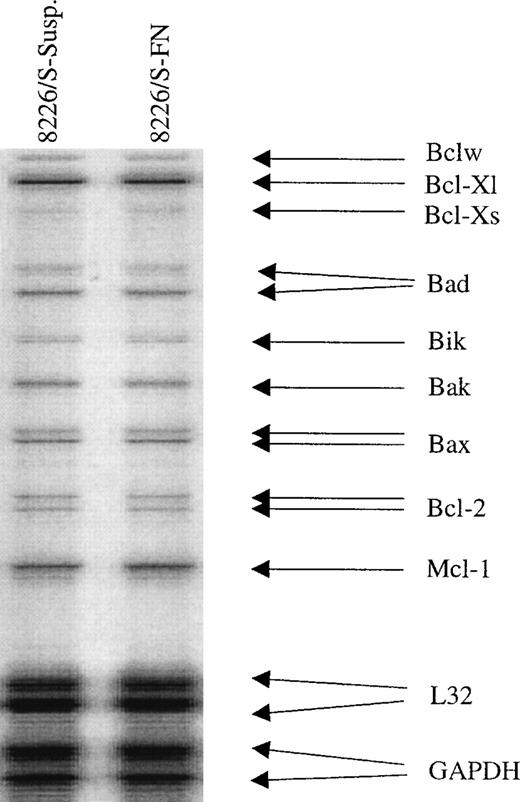

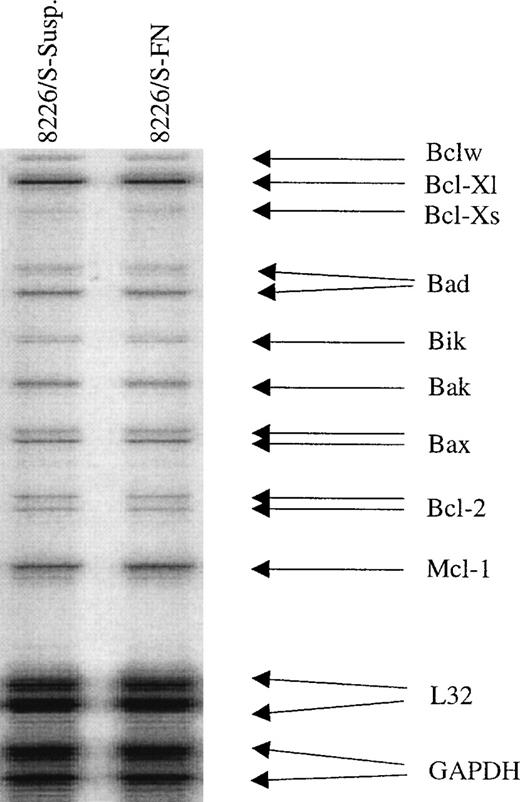

BCL-2 and BCL-XL are widely known to inhibit the onset of programmed cell death, and others have demonstrated the ability of β1 integrins to upregulate at least one of these genes.14 46 To investigate whether expression of the Bcl-2 family members known to suppress (Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL) or promote (BAX and Bcl-XS) apoptosis were altered in FN-adhered cells, an RNase protection assay was used to observe possible transcriptional changes in these genes. Expression levels and ratios of all Bcl-2 family members were found to be unchanged, and therefore altered RNA levels of these apoptosis regulating proteins are not likely responsible for protecting FN-adhered myeloma cells from acute cytotoxic drug exposure (Fig3). To confirm these results, semi-quantitative RT-PCR for Bcl-2, Bcl-Xl, Bcl-Xs, and BAX was performed on RNA collected from three different cell samples. As in the RNase protection assay, no significant changes in the levels of these genes were observed in FN-adhered cells.

RNA levels of Bcl-2 family members are unchanged following FN adhesion. Drug sensitive 8226/S cells were adhered to FN-coated plates or grown in suspension for 24 hours after which total RNA was collected and analyzed by RNase protection. Expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping genes GAPDH and L32.

RNA levels of Bcl-2 family members are unchanged following FN adhesion. Drug sensitive 8226/S cells were adhered to FN-coated plates or grown in suspension for 24 hours after which total RNA was collected and analyzed by RNase protection. Expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping genes GAPDH and L32.

Intracellular doxorubicin accumulation and expression of known drug transporters are not altered by FN adhesion.

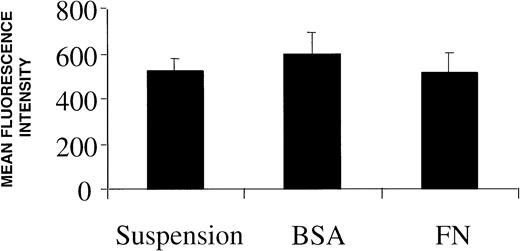

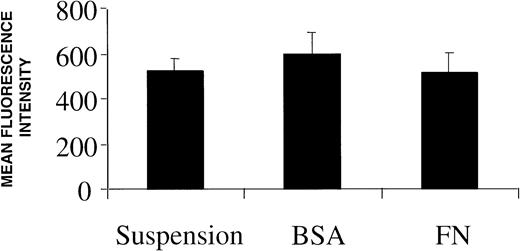

Based on the knowledge that active drug transport is a common mechanism of doxorubicin resistance and that in rare instances ECM adhesion can upregulate P-glycoprotein,9 we looked for possible reductions in intracellular drug accumulation in adhered myeloma cells. A flow cytometry-based intracellular drug accumulation assay revealed that the concentration of doxorubicin, which emits at 573 nm after excitation, in FN-adhered myeloma cells is equal to that seen in nonadhered controls (Fig 4). Due to the fact that some drug transporters may alter nuclear drug concentration with minimal effects on total intracellular drug,47 we used RT-PCR to investigate whether three known transport proteins were upregulated by FN adhesion. Two members of the ABC superfamily of transmembrane gycoproteins, MDR1 (encoding P-glycoprotein) and MRP (encoding the multidrug resistance-associated protein), which are known to actively extrude drugs such as doxorubicin, were unchanged following FN adhesion (data not shown). Expression of LRP (lung resistance-associated protein), which has also been associated with drug resistance, was also unchanged in adhered myeloma cells compared with suspension cells (data not shown). In addition to ruling out altered drug transport as a mechanism of adhesion-based drug resistance, these studies also show that ECM components of the bone marrow microenvironment probably do not affect the intrinsic expression of these drug transporters in human myeloma cells.

Intracellular doxorubicin concentration is unaffected by culturing cells on plastic, BSA, or FN. Following a 24-hour incubation on each surface, 10 μmol/L doxorubicin was added to each well for 1 hour and cells were analyzed for drug accumulation differences by flow cytometry. Bars are the SD of n = 6 from two independent experiments.

Intracellular doxorubicin concentration is unaffected by culturing cells on plastic, BSA, or FN. Following a 24-hour incubation on each surface, 10 μmol/L doxorubicin was added to each well for 1 hour and cells were analyzed for drug accumulation differences by flow cytometry. Bars are the SD of n = 6 from two independent experiments.

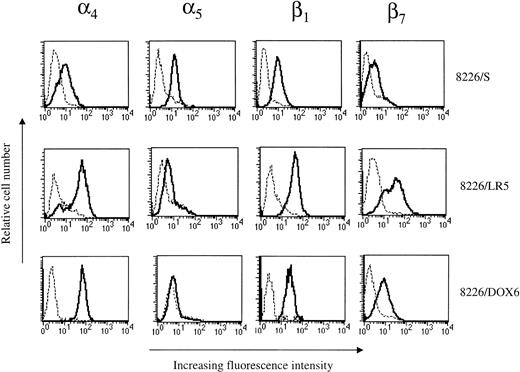

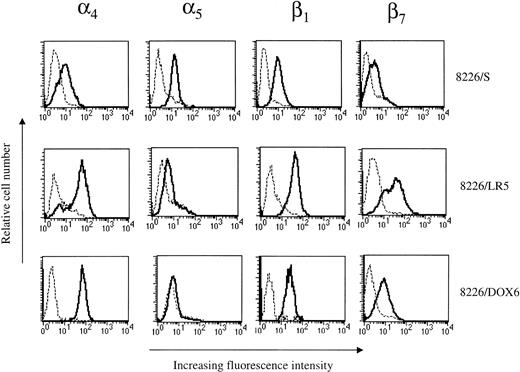

VLA-4 is overexpressed in drug-resistant variants of the 8226/S myeloma cell line.

Low-level drug-resistant variants were selected from the 8226/S drug-sensitive human myeloma cell line using step-wise increases in melphalan or doxorubicin over a period of approximately 10 months.38 39 The acquired resistance of the 8226/LR5 (L-phenylalanine mustard resistant) cell line is based on the overexpression of glutathione and glutathione-associated enzymes. 8226/DOX6 (doxorubicin resistant) acquired a P-glycoprotein based mechanism of resistance after chronic drug selection. Both of these cell lines were assayed for changes in cell surface integrin expression. Cell lines were incubated with MoAbs to the α4, α5, β1, or β7 integrin subunits, followed by labeling with an FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. In both 8226 cell line variants, acquired resistance to doxorubicin or melphalan was associated with an increase in α4 surface expression as determined by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis (Fig5, Table 1). When compared with levels found in the 8226/S parent line, α4 subunit expression was increased fourfold in both 8226/LR5 and 8226/DOX6 (n = 3). β1 subunit expression increased 2.5-fold in 8226/LR5 while a more modest increase of 70% was seen in 8226/DOX6 when compared with parent cell line levels. β7 integrin, the only other integrin subunit known to heterodimerize with α4, was increased 3.6-fold in 8226/LR5 but remained unchanged in 8226/DOX6. α5expression levels remained relatively low in both 8226 drug selected cell lines.

Phenotypic analysis of 8226 cell surface FN receptor expression by flow cytometry. Integrin subunit expression by drug-sensitive (8226/S), melphalan-resistant (8226/LR5), and doxorubicin-resistant (8226/DOX6) cell lines were analyzed using MoAbs for 4, 5, β1, and β7. Cells were incubated with an integrin-specific MoAb (—) or with irrelevant control Ab (---), followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated secondary Ab. Ten thousand events were analyzed for each sample using a FACScan machine (Becton-Dickinson); histograms are representative of three different experiments.

Phenotypic analysis of 8226 cell surface FN receptor expression by flow cytometry. Integrin subunit expression by drug-sensitive (8226/S), melphalan-resistant (8226/LR5), and doxorubicin-resistant (8226/DOX6) cell lines were analyzed using MoAbs for 4, 5, β1, and β7. Cells were incubated with an integrin-specific MoAb (—) or with irrelevant control Ab (---), followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated secondary Ab. Ten thousand events were analyzed for each sample using a FACScan machine (Becton-Dickinson); histograms are representative of three different experiments.

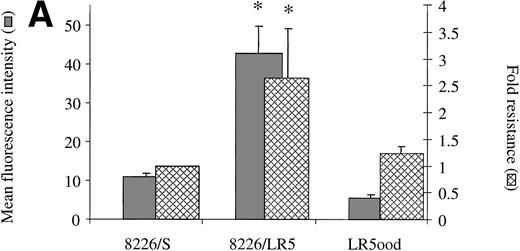

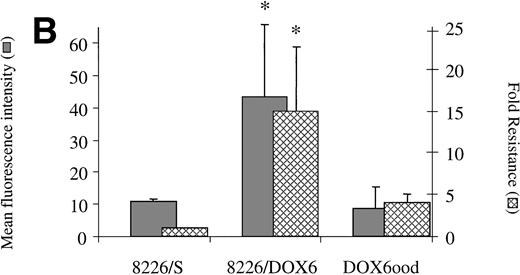

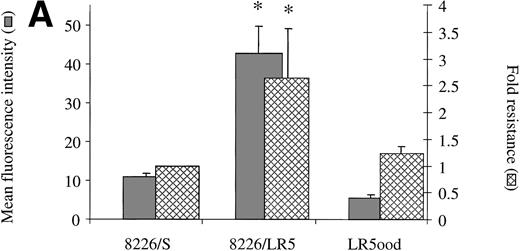

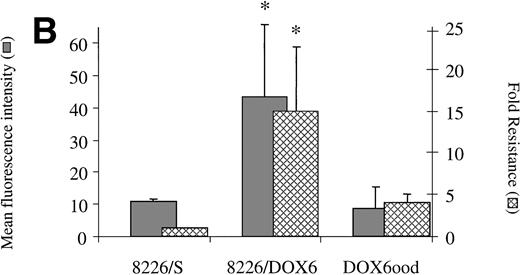

Drug sensitive revertant cell lines express α4 levels equal to that of 8226/S.

When removed from drug for a period of 20 weeks, 8226/LR5 reverted back to a drug-sensitive phenotype with α4 integrin expression comparable with the drug sensitive parent cell line 8226 (Fig6A). The level of α5 remained low in the revertant cell line as well (data not shown). The same observations were made when 8226/DOX6 were removed from maintenance drug for 20 weeks (Fig 6B). These experiments demonstrate a correlation between levels of α4 expression and drug resistance in the 8226 myeloma cell line. Acute exposure of 8226/S to a wide range of concentrations of doxorubicin or melphalan had no immediate effects (1 to 48 hours) on cell surface integrin expression, as determined by FACS analysis (data not shown), suggesting a process of selection for α4 overexpression, rather than drug-induced upregulation of this gene.

(A) Drug resistance is associated with α4expression in melphalan-resistant (8226/LR5) and revertant (LR5ood) cell lines. 8226/LR5 were maintained in 5 × 10−5 mmol/L melphalan (LPAM) and LR5ood were maintained out of drug for 20 weeks. 4 expression was measured by flow cytometry and drug resistance was measured by MTT cytotoxicity analysis. Resistance values are reported as the IC50 dose of LPAM relative to 8226/S. 4 expression levels and melphalan resistance levels of 8226/LR5 were found to be higher than 8226/S (P < .05). 4 expression and melphalan resistance of LR5ood were found to be equal to those of the 8226/S parent line. Bars are the SD of three different experiments. (B) Drug resistance is associated with 4 expression in doxorubicin-resistant (8226/DOX6) and revertant (DOX6ood) cell lines. 8226/DOX6 were maintained in 6 × 10−8 mol/L doxorubicin and DOX6ood were maintained out of drug for 20 weeks. 4 expression was measured by flow cytometry and drug resistance was measured by MTT cytotoxicity analysis. Resistance values are reported as the IC50 dose of doxorubicin relative to 8226/S. 4 expression levels and doxorubicin resistance levels of 8226/DOX6 were found to be higher than 8226/S (P < .05). 4 expression and doxorubicin resistance of DOX6ood were found to be equal to those of the 8226/S parent line. Bars are the SD of three different experiments.

(A) Drug resistance is associated with α4expression in melphalan-resistant (8226/LR5) and revertant (LR5ood) cell lines. 8226/LR5 were maintained in 5 × 10−5 mmol/L melphalan (LPAM) and LR5ood were maintained out of drug for 20 weeks. 4 expression was measured by flow cytometry and drug resistance was measured by MTT cytotoxicity analysis. Resistance values are reported as the IC50 dose of LPAM relative to 8226/S. 4 expression levels and melphalan resistance levels of 8226/LR5 were found to be higher than 8226/S (P < .05). 4 expression and melphalan resistance of LR5ood were found to be equal to those of the 8226/S parent line. Bars are the SD of three different experiments. (B) Drug resistance is associated with 4 expression in doxorubicin-resistant (8226/DOX6) and revertant (DOX6ood) cell lines. 8226/DOX6 were maintained in 6 × 10−8 mol/L doxorubicin and DOX6ood were maintained out of drug for 20 weeks. 4 expression was measured by flow cytometry and drug resistance was measured by MTT cytotoxicity analysis. Resistance values are reported as the IC50 dose of doxorubicin relative to 8226/S. 4 expression levels and doxorubicin resistance levels of 8226/DOX6 were found to be higher than 8226/S (P < .05). 4 expression and doxorubicin resistance of DOX6ood were found to be equal to those of the 8226/S parent line. Bars are the SD of three different experiments.

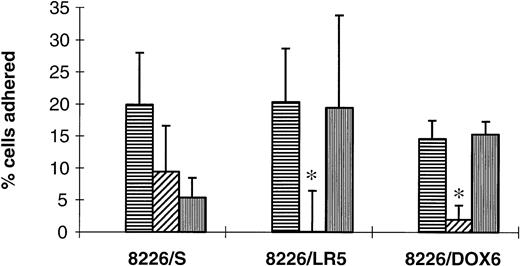

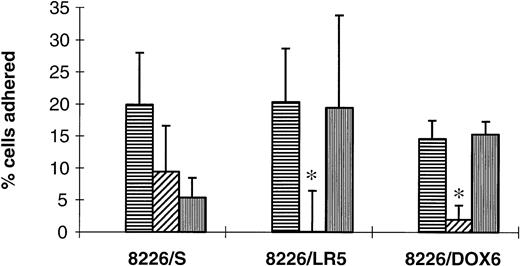

Drug-resistant 8226 cell lines demonstrate increased levels of α4-mediated FN adhesion.

Functionality of surface VLA-4 and VLA-5 was investigated using a fibronectin adhesion assay with precoated microtiter plates. BSA was used to control for nonspecific cell adhesion and several MoAbs were used to inhibit α5 (P1D6)- and α4 (P4G9 and HP2/1)-mediated adhesion. Cell lines selected from 8226/S by continuous drug exposure displayed significant increases in α4-mediated FN binding ability (Fig7) compared with the parent cell line, 8226/S, which used both α5 and α4 for FN adherence. This class switch of integrins functioning in adherence may be indicative of an advantage in α4- versus α5-mediated signal transduction during the selection process, although further study is needed to investigate these possibilities.

Contribution of 4 and α5integrin subunits to FN adhesion. Drug-sensitive (8226/S), melphalan-resistant (8226/LR5), and doxorubicin-resistant (8226/DOX6) were adhered to FN-coated wells (horizontal striped bars) for 1 hour. In order to determine percentage binding due to 4 and 5, some cells were pre-incubated with 4function blocking Ab P4G9 (hatched bars) or 5 function blocking Ab P1D6 (vertical striped bars) for 15 minutes before application to wells. FN adhesion by 8226/S was found to be mediated equally by 4 and 5, while FN adhesion for both drug-resistant cell lines was mediated only by 4(P < .05), as determined by complete inhibition of adherence using the 4 blocking Ab. Total FN adhesion mediated by 4 was also higher in drug-resistant lines compared with drug-sensitive 8226/S (P < .05). Values shown are the percentage of total cells applied to each well corrected for nonspecific adhesion to BSA-coated wells. Bars are the SD of n = 6 from three different experiments.

Contribution of 4 and α5integrin subunits to FN adhesion. Drug-sensitive (8226/S), melphalan-resistant (8226/LR5), and doxorubicin-resistant (8226/DOX6) were adhered to FN-coated wells (horizontal striped bars) for 1 hour. In order to determine percentage binding due to 4 and 5, some cells were pre-incubated with 4function blocking Ab P4G9 (hatched bars) or 5 function blocking Ab P1D6 (vertical striped bars) for 15 minutes before application to wells. FN adhesion by 8226/S was found to be mediated equally by 4 and 5, while FN adhesion for both drug-resistant cell lines was mediated only by 4(P < .05), as determined by complete inhibition of adherence using the 4 blocking Ab. Total FN adhesion mediated by 4 was also higher in drug-resistant lines compared with drug-sensitive 8226/S (P < .05). Values shown are the percentage of total cells applied to each well corrected for nonspecific adhesion to BSA-coated wells. Bars are the SD of n = 6 from three different experiments.

DISCUSSION

Classically, investigations of drug resistance have focused on the single cell by selecting for drug resistant cells following exposure to cytotoxic agents. By and large, these studies have revealed mechanisms that reduce intracellular drug concentration (P-glycoprotein, MRP, LRP), detoxify the drug itself (changes in glutathione and glutathione-associated enzymes) or alter the drug target (alterations in topoisomerase II). However, both preclinical and clinical studies indicate that these mechanisms are unlikely to determine initial drug response. It is clear that integrins and ECM interactions play critical roles in cell survival. The evidence presented here suggests that during the course of initial or chronic drug exposure, myeloma cells overexpressing VLA-4 may have a selection advantage over cells expressing low levels of this protein. Experiments involving the treatment of 8226/S with short term (1 to 48 hours) doses of doxorubicin or melphalan indicate that increases in α4expression are not seen immediately, probably ruling out drug-induced transcriptional upregulation as a reason for FN receptor overexpression. Drug-resistant cells removed from chronic drug exposure eventually lose their high α4 expression levels along with their resistant phenotype, implicating selection pressure as a prerequisite for α4 upregulation. This correlation between integrin expression and resistance levels was seen in both doxorubicin- and melphalan-selected variants of 8226/S. There have been previous links observed between cytotoxic drug exposure and integrin expression and function involving other tumor cell types.48,49 Scotlandi et al and Nista et al also showed integrin upregulation in multidrug resistant osteosarcoma and breast cancer cells, respectively.50 51 Although most of these studies focused on metastatic changes in tumor cells, they do indicate that the effects of common DNA damaging agents on integrin expression and function may not be limited to malignant plasma cells. We have demonstrated, through two distinct apoptosis assays, that cells in direct contact with immobilized FN are less sensitive to acute doxorubicin treatment. A decreased response to melphalan in FN-adhered cells was not consistently observed during acute exposure using MTT cytotoxicity analysis (possibly as a result of assay insensitivity); however, significant increases in cell survival were detected using Annexin V. Although the level of cytoprotection may be small following an acute survival assay, these differences may be sufficient to give rise to a large phenotypically distinct population over the course of chronic drug exposure in vitro or in vivo (a hypothesis currently under investigation in our laboratory).

It is not entirely clear whether physical cellular adhesion and spreading is required for integrin-mediated signal transduction. Bozzo et al demonstrated that soluble ECM components applied to suspension cells can activate β1 integrin signaling and suppress apoptosis in the absence of cell adhesion and spreading.46By this reasoning, soluble FN may have the capacity to induce β1 signaling without adhesion within myeloma cell cultures. The overexpression and use of α4 for FN adhesion by drug-resistant myeloma cell lines may indicate a consequent increase in the number of intercellular interactions (through FN binding, VCAM-1 binding, or homotypic α4binding52) by tumor cells exposed to DNA damaging agents, or the increased binding of soluble FN from serum. It has been shown that many cultured myeloma cell lines, including 8226, produce a relatively high amount of cell surface FN compared with normal plasma cells, an observation also seen clinically in patient specimens.53,54 DNA damaging agents such as doxorubicin or melphalan may also induce increased production of ligand, as was shown with human mesangial cell cultures and FN synthesis.55Cells under selection pressure may then use soluble or cell-bound integrin ligands, and subsequent α4-mediated signaling, as a cytoprotective mechanism.

Some previously established mechanisms of drug resistance were investigated as possible causes of the cytoprotective effect of FN seen in our assays. Since drug transporters such as P-glycoprotein have been well documented mediators of drug resistance in myeloma cells, we investigated possible alterations in intracellular drug concentration following adhesion. FN-adhered cells were found to contain doxorubicin levels equal to those seen in nonadhered cells using standard techniques. In some cases, intracellular drug compartmentalization can be altered by P-glycoprotein without high levels of drug extrusion,47 for this reason the expression of three drug transporters was analyzed by semi-quantitative RT-PCR.44 56The expression of MDR1, MRP, and LRP were all equal between FN-adhered and nonadhered cells, probably ruling out induction of active drug transport as a possible mechanism of cytoprotection in these experiments.

Another family of proteins known to effect apoptosis and drug response is the Bcl-2 family. VLA-5 and VLA-6 are known, in certain cell types, to upregulate Bcl-2 and protect against apoptosis following ligation with FN or laminin, respectively. RNase protection and RT-PCR assays showed the RNA levels coding for this protein to be unchanged in FN-adhered cells. Furthermore, expression levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-XL, which is upregulated in keratinocytes following adhesion,57 were unchanged following FN adhesion. No changes in the expression of other anti-apoptotic (Bcl-w and Mcl-1) or pro-apoptotic genes (BAX, Bcl-XS, Bad, and Bik) were detected by either of these assays. However, until further investigation, we cannot rule out the possibility that integrins affect posttranslational modification of these proteins and their potential participation in CAM-DR.

Several investigations have put new found significance on the effects of adhesion on cell cycle kinetics and how this may impart drug resistance on tumor cells.8 VLA-4–mediated adhesion is known to decrease the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells58 and the α4 over-expressing cell lines 8226/LR5 and 8226/DOX6 have longer doubling times in culture compared with the 8226/S parent cell line (LR5 = 30 hours, DOX6 = 39 hours, S = 27 hours), (Bellamy et al,39 and unpublished findings, February 1997). Further studies are required before a kinetic mechanism of altered drug response can be implicated in playing a role in FN-mediated cytoprotection.

Many recent reports have implicated the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3 kinase)/AKT pathway as having a major influence on cellular apoptotic commitment and PI3 kinase activation is a known inhibitor of apoptosis in hematopoietic cells.59-62 Future studies will focus on this pathway as a likely mechanism of apoptotic suppression in FN-adhered cells. Although FN adhesion and VLA-4 ligation is known to initiate the PI3 kinase signaling cascade in some cases, VLA-4 or VLA-5 have not yet been directly correlated with this pathway in myeloma cells.63 Furthermore, a frequent association has been observed between these integrins and FAK, a known activator of PI3 kinase.32,64-66 Through activation by PI3-K lipid products or by direct phosphorylation, AKT is known to phosphorylate the Bcl-XL/Bcl-2–associated death promoter (BAD), promoting cell survival possibly by dissociating it from Bcl-XL and decreasing the amount of BAX homodimers.61 The endpoint of the PI3-K/AKT signaling cascade probably involves an eventual blockade of ced3/ICE activity and a subsequent inhibition of tumor cell death, as has been reported in some cases of cell–ECM interactions.59 67

In summary, we have found a link between integrin-mediated FN adhesion and decreased response to chemotherapeutic drugs as well as a correlation between the expression of α4 integrin heterodimers and drug resistance. We have used the term “cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance,” or CAM-DR, to describe this observation. Although the intracellular mechanisms mediating this survival signal are as yet unknown, two well-established causes of drug resistance, active drug transport and increased expression of Bcl-2 family members, have been ruled out. Clinically, elevated FN receptor expression or function in myeloma cells within the bone marrow may be an indicator of a more aggressive tumor cell that has a survival advantage against the cytotoxic effects of anti-cancer drugs. In vivo alterations in fibronectin receptor expression or function may have a magnified effect on myeloma cell survival when they are in direct association with stromal cells and ECM components of the bone marrow. The cytoprotection conferred by fibronectin receptors may be low level, but intrinsic, since most myeloma cells inherently express moderate to high levels of these integrins. Small changes in drug sensitivity in vitro are probably highly relevant clinically since even a 1% surviving tumor fraction can have drastic long-term consequences. The CAM-DR mediated by FN adhesion may be sufficient to allow the eventual emergence of drug resistance mechanisms such as upregulation of P-glycoprotein, MRP, and alterations in topoisomerase II, which then become the predominant cytoprotective processes. Once their role in myeloma is firmly established, specific integrin subunits and the various signal transduction elements they use, may prove to be promising therapeutic targets. Established antagonists of VLA-4 and VLA-5 integrin function may serve as chemosensitizers when administered in conjunction with conventional chemotherapeutics, possibly leading to higher levels of drug response and improved clinical outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Ibrahim Buyuksal for his help in performing the RNase protection assays, and Marc Oshiro for his help in the PCR assays.

Supported in part by CA 17094 (WSD).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to William S. Dalton, PhD, MD, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, 12902 Magnolia Dr, Tampa, FL 33612; e-mail:dalton@Moffitt.usf.edu.