Normal B-lymphocyte maturation and proliferation are regulated by chemotactic cytokines (chemokines), and genetic polymorphisms in chemokines and chemokine receptors modify progression of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infection. Therefore, 746 HIV-1–infected persons were examined for associations of previously described stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) chemokine and CCR5 and CCR2 chemokine receptor gene variants with the risk of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). The SDF1-3′A chemokine variant, which is carried by 37% of whites and 11% of blacks, was associated with approximate doubling of the NHL risk in heterozygotes and roughly a fourfold increase in homozygotes. After a median follow-up of 11.7 years, NHL developed in 6 (19%) of 30 SDF1-3′A/3′A homozygotes and 22 (10%) of 202 SDF1-+/3′A heterozygotes, compared with 24 (5%) of 514 wild-type subjects. The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-protective chemokine receptor variant CCR5-▵32 was highly protective against NHL, whereas the AIDS-protective variant CCR2-64I had no significant effect. Racial differences in SDF1-3′A frequency may contribute to the lower risk of HIV-1–associated NHL in blacks compared with whites. SDF-1 genotyping of HIV-1–infected patients may identify subgroups warranting enhanced monitoring and targeted interventions to reduce the risk of NHL.

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY virus-1 (HIV-1)–infected individuals are at greatly increased risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which arises as a late complication in the setting of advanced immunodeficiency.1-3 These HIV-1–associated lymphomas are characteristically of B-cell immunophenotype and high-grade histology (including Burkitt’s and Burkitt’s-like, immunoblastic, and large-cell diffuse) and frequently involve extranodal primary sites (especially the central nervous system).4 Heterogeneous acquired genetic lesions are present in varying subsets of these tumors, including activation of the c-myc (especially in Burkitt’s lymphoma), BCL-6, and ras proto-oncogenes and inactivation of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene.5 Episomal Epstein-Barr virus DNA is often detectable, especially in primary central nervous system tumors.6

The pathogenesis of HIV-1–related B-cell lymphoma is poorly understood, but may be related to HIV-induced immune dysregulation. HIV-1–infected individuals maintain a state of chronic B-cell hyperactivation and hyperproliferation, which may be a consequence of disruption of the normal steady-state cytokine network and/or direct stimulation by binding of HIV.7,8 Lymphomagenesis may be a multistage process progressing from this polyclonal B-cell proliferation to oligoclonal expansion of antigen-selected clones and subsequent outgrowth of a monoclonal tumor.9

Chemokines are cytokines that are produced and act locally in tissues to attract and stimulate lymphocytes at sites of infection and inflammation.10 A candidate chemokine mediating B-cell hyperproliferation in HIV-1 infection is stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), a member of the CXC family of polypeptide chemokines. SDF-1 is a potent mitogen and chemoattractant for B cells and B-cell precursors, which is constitutively expressed by bone marrow stromal cells and in other tissues.11,12 SDF-1 is a natural ligand of the G-protein–coupled seven transmembrane receptor, CXC-chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4),13-16 and downmodulates CXCR4 surface expression on T-lymphocyte cell lines.17 CXCR4 also functions as a coreceptor for T-cell–tropic HIV-1 isolates,13,14,18 and SDF-1 blocks cellular entry of T-cell–tropic HIV-1 in vitro.13 14

The SDF1 gene is polymorphic, and a variant with a G-to-A transition at position 801 of the 3′ untranslated region of the SDF-1β gene transcript (designated SDF1-3′UTR-801G-A, and abbreviated as SDF1-3′A) has an allele frequency of 21% in whites and 6% in blacks in the United States.19 SDF1-3′A/3′A homozygotes have been variably reported to have slower19 or faster20,21 progression of HIV-1 infection to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and death. Polymorphisms in two chemokine receptor genes, CCR5 and CCR2, have been reported to be protective against HIV-1. A 32-bp deletion in the coding region of the CCR5 gene, termed CCR5-Δ32, and a valine to isoleucine substitution at position 64 in the transmembrane domain of CCR2, termed CCR2-64I, are each protective in heterozygotes against progression to AIDS.22-25 CCR5-Δ32 homozygotes are also strongly protected against HIV-1 infection, but an effect of CCR2-64I on risk of infection has not been demonstrated.22-25 Because interactions between chemokines and chemokine receptors may be important regulators of B-cell activation and proliferation, we examined the associations of previously described SDF-1, CCR5, and CCR2 genetic polymorphisms with the risk of NHL in 3 HIV-1–infected cohorts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research subjects came from three National Cancer Institute (NCI) cohort studies of HIV-1–infected patients. One-hundred forty-six were HIV-1–infected children receiving care from the HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch (formerly a part of the Pediatric Branch), NCI, of which 129 (88%) were infected neonatally.26 One hundred twenty were HIV-1–infected male homosexuals and 480 were HIV-1–infected hemophilia patients in two cohorts observed by the Viral Epidemiology Branch, NCI.27 28 Median age at HIV-1 seroconversion was 33.2 years for the homosexual cohort and 20.2 years for the hemophilia cohort. Additionally, 24 HIV-1–uninfected patients with NHL observed in other NCI studies were included. All studies were approved by institutional review boards of NCI and at collaborating institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from each subject (or his or her guardian).

Dates of HIV-1–seroconversion were estimated as previously described for each cohort.26-28 Incident cases of NHL and other AIDS-defining clinical conditions were ascertained at follow-up visits and from clinical records. Lymphoma cases were categorized by primary site (as central nervous system v systemic) and, for systemic tumors, by histologic subtype (as Burkitt’s and Burkitt-like vall other). Diagnoses of NHL made at other institutions were verified at the NCI by examination of biopsy specimens (when available) and by review of pathology reports. Data through February 1998 for the pediatric cohort (median follow-up, 8.6 years) and through December 1997 for the homosexual (8.7 years) and hemophilia (12.6 years) cohorts were used in this analysis.

SDF1-3′A genotyping was performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNA by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay, as previously described.19 CCR5-Δ32 genotyping was performed by single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis, as previously described.23 CCR2-64I genotyping was performed by SSCP and PCR-RFLP, as previously described.22 c-myctranslocations in circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells were detected by nested PCR, as previously described.29

Odds ratios were computed from the prevalence of variant genotypes in subjects with and without NHL or other AIDS-defining clinical conditions; odds ratios for NHL subtypes were computed from the odds in subjects with a given subtype versus the odds in subjects without NHL.P values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) on odds ratios were calculated by Fisher’s exact test, using Epi-Info version 5.0 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) and STATA version 5.0 (STATA Press, College Station, TX) software packages. Cox proportional hazard regression modelling was performed to examine the effect of SDF1-3′A on incidence of NHL after HIV-1 infection, using the PHREG procedure in PC-SAS version 6.12 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) statistical software. Covariates in these models included race (categorized as white, black, and other), age at seroconversion (categorized in approximate tertiles as <12, 12 to 29, and >29 years), and CCR5-Δ32 and CCR2-64I polymorphisms (categorized as present [homozygous or heterozygous] and absent). Initial models included separate terms for homozygous and heterozygous SDF1-3′A genotypes; gene dose-effect was then estimated using a single term for the number of allelic copies (0, 1, or 2) of SDF1-3′A.

RESULTS

SDF1-3′A carriers were at increased risk of NHL, and homozygotes had a higher risk than heterozygotes. After a median follow-up of 11.7 years, 6 (19%) of 30 SDF1-3′A/3′A subjects and 22 (10%) of 202 SDF1-+/3′A subjects developed lymphoma, compared with 24 (5%) of 514 wild-type subjects (P < .01 for both comparisons). The increased risk was particularly pronounced for Burkitt’s and Burkitt-like tumors (5 of 6 cases occurred in SDF1-3′A carriers), although other high-grade systemic tumors and primary brain lymphomas were also increased (Table 1). SDF1-3′A was not significantly associated with risk of Kaposi’s sarcoma in male homosexuals, based on 23 genotyped cases. SDF1-3′A homozygotes had a slightly decreased frequency of opportunistic infection (ie, AIDS-indicator clinical conditions other than NHL and Kaposi’s sarcoma), but the numbers were small and not statistically significant.

Because of the striking association with HIV-1–associated Burkitt’s lymphoma, an additional 20 HIV-1–negative Caucasians with Burkitt’s/Burkitt-like lymphoma were evaluated for SDF1 genotype. Five (25%) were SDF1-3′A carriers (all heterozygous) and 15 (75%) were wild-type. Four HIV-1–uninfected Caucasians with NHL of other histologies were also tested; all 4 were wild-type for SDF1.

CCR5-Δ32 appeared to be protective against HIV-1–associated lymphoma, with 2 (2%) of 98 CCR5-Δ32 carriers developing NHL, compared with 49 (8%) of 619 wild-type subjects (P = .03; Table 2). Conversely, the protective effect of CCR2-64I against AIDS appeared to be restricted to an effect on opportunistic infection, because 7 (6%) of 120 CCR2-64I carriers developed NHL, compared with 22 (5%) of 466 wild-type subjects (Table2).

Thirteen (12%) of 110 subjects in the homosexual cohort were previously reported to have detectable c-myc translocations in circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells.29 The frequency of these translocations in subjects with chemokine and chemokine receptor polymorphisms was similar to that of the overall cohort. In those with sufficient DNA for the current analysis, 4 (11%) of 36 SDF1-3′A carriers, 1 (6%) of 16 CCR5-Δ32 carriers, and 4 (18%) of 22 CCR2-64I carriers had circulating c-myc detected on one or more occasions.

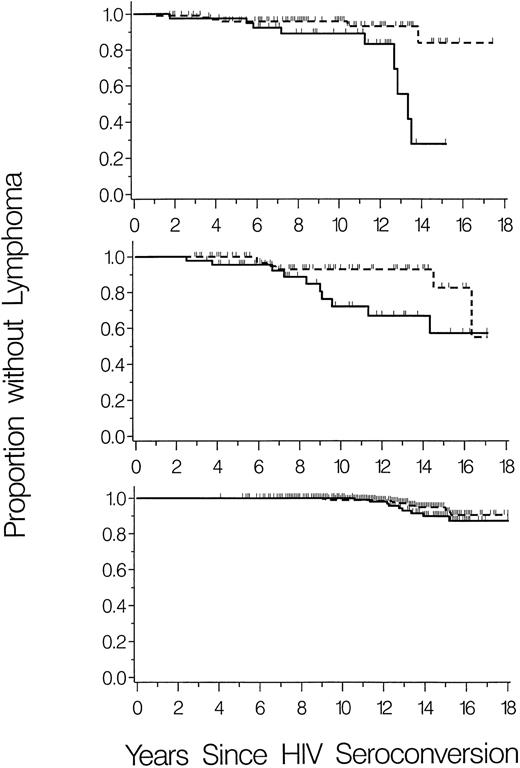

To further investigate the relationship of SDF1-3′A with HIV-1–associated-NHL, lymphoma-free survival was graphed separately for the three cohorts. The cohorts differed in overall risk of NHL, which occurred in 15 (10%) of 146 HIV-1–infected children and 16 (13%) of 120 HIV-1–infected male homosexuals (P = .5), compared with only 21 (4%) of 480 HIV-1–infected hemophilia patients (P = .01 and P = .001 v pediatric and homosexual cohorts, respectively). However, cumulative incidence of NHL was consistently higher in SDF1-3′A carriers (heterozygous plus homozygous) compared with homozygous wild-type for all three cohorts (Fig 1).

Cumulative incidence of NHL in carriers (heterozygous plus homozygous) of SDF1-3′A (solid lines) compared with homozygous wild-type (dashed lines). Vertical ticks represent censoring times of subjects without NHL. (Top panel) HIV-1–infected children (N = 146). (Middle panel) HIV-1–infected male homosexuals (N = 120). (Bottom panel) HIV-1–infected hemophilia patients (N = 480).

Cumulative incidence of NHL in carriers (heterozygous plus homozygous) of SDF1-3′A (solid lines) compared with homozygous wild-type (dashed lines). Vertical ticks represent censoring times of subjects without NHL. (Top panel) HIV-1–infected children (N = 146). (Middle panel) HIV-1–infected male homosexuals (N = 120). (Bottom panel) HIV-1–infected hemophilia patients (N = 480).

Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to estimate the relative hazards of AIDS-lymphoma associated with heterozygous and homozygous SDF1-3′A (all models were stratified by cohort to account for variation in lymphoma risk). Compared with the wild-type, SDF1-3′A was associated with approximate doubling of the NHL hazard in heterozygotes and roughly a fourfold increase in homozygotes (Table 3). Adjustment for race, age at seroconversion, and CCR5-Δ32 and CCR2-64I polymorphisms did not appreciably alter the estimates. The adjusted relative hazard of NHL per copy of the SDF1-3′A allele was 2.0 (95% CI, 1.3 to 3.1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, SDF1-3′A carriers in all three cohorts had an increased absolute risk of NHL, which cannot be explained by an influence (either favorable or unfavorable) on other AIDS outcomes. The intermediate risk of SDF1-3′A heterozygotes indicates that the variant allele is codominant in its effect on the incidence of HIV-1–associated NHL. As compared with the other two cohorts, the lower NHL risk of the hemophilia patients, half of whom became infected in childhood, corresponds to the slower course of HIV-1 disease in children (excluding those neonatally infected) compared with adults.28

Although the numbers were small, the chemokine receptor polymorphisms tended to have mutually exclusive effects on the risks for either HIV-1–associated lymphoma or other AIDS outcomes. CCR2-64I appeared protective against opportunistic infection but not NHL, whereas CCR5-Δ32 appeared strongly protective against NHL but not opportunistic infection.

In the HIV-1–infected subjects, SDF1-3′A was particularly associated with Burkitt’s and Burkitt-like lymphoma, histologic subtypes that uniformly have a c-myc activating chromosomal translocation. However, SDF1-3′A was not associated with detection of c-myc translocations in HIV-1–infected subjects without lymphoma. The association of Burkitt’s lymphoma with SDF1-3′A contrasts with that tumor’s phenotypic resemblance to germinal center lymphocytes (reviewed by Magrath and Bhatia30), because germinal center B cells may be unresponsive to SDF1.31 SDF1-3′A was not associated with increased risk of Burkitt’s and Burkitt-like lymphomas in the absence of HIV-1 infection, suggesting that this polymorphism may be phenotypically silent unless triggered by HIV-1.

Based on the adjusted relative hazards from the Cox proportional hazards model and the reported allele frequencies of SDF1-3′A, the etiologic fraction32 of HIV-1–associated-NHL (ie, proportion of cases in the population attributable to SDF1-3′A) may be estimated as 36% for whites and 10% for blacks. Correspondingly, among reported US AIDS cases, NHL is approximately one half as common among blacks than in whites (relative risks of 0.31, 0.61, and 0.39 for Burkitt’s, primary brain, and immunoblastic lymphoma, respectively).1 Thus, differences in SDF1-3′A allele frequency may partially explain racial differences in incidence of HIV-1–associated NHL.

SDF1-3′A differs from the wild-type in an untranslated region of the structural gene transcript. The physiologic effect of this variation is not known, but may be associated with overexpression of SDF-1 protein, which in turn stimulates B-lymphocyte proliferation. HIV-1 infection may be a necessary cofactor for increased SDF1 protein production or for a B-cell proliferative response. Alternatively, HIV-1–induced immunodysregulation may be required for such B-cell stimulation to lead to lymphomagenesis. Paradoxically, increased levels of SDF-1 may protect T lymphocytes against HIV-1 infection but predispose B lymphocytes to malignant transformation.

The marked protection against NHL by the CCR-5-Δ32 mutation would not be predicted from known physiologic functions of the CCR5 chemokine receptor. Conceivably, the protective effect may be due to enhanced control of replication of HIV or some tumorigenic coinfection (eg, the Epstein-Barr virus).

The greatly increased risk of HIV-1–associated NHL in SDF1-3′A carriers suggests clinical utility of SDF-1 genotyping. HIV-1–infected patients with the SDF1-3′A gene variant may warrant enhanced monitoring for earlier detection and treatment of NHL. Such patients have a potentially modifiable risk factor for HIV-1–associated NHL that should be a target for development of preventive interventions.

Chemokine and chemokine receptor manipulations could serve as novel approaches for ameliorating the effects of HIV-1 on the immune system. The paradoxical effects of these genetic polymorphisms on the risks of lymphoma and opportunistic infections represents an additional challenge in designing chemokine-related therapies for HIV-1 infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Kishor Bhatia, Paul Levine, and Konrad Huppi for providing DNA samples from Burkitt’s lymphoma patients; Robert Wittes, Brigitta Mueller, Anne Marie Boler, and Melissa Adde for helpful discussions; the collaborators and study managers for the Washington and New York Men’s Research Study and the Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study for providing clinical data; Frances Yellin for performing statistical analyses; and Ian Magrath for providing critical advice.

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute Contracts No. NO1-CP-40501 and NO1-CP-33002 with Research Triangle Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This is a US government work. There are no restrictions on its use.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Charles S. Rabkin, MD, Viral Epidemiology Branch, National Cancer Institute, MSC 7248, Bethesda, MD 20892.