Abstract

The role of the homeobox gene HOXA5 in normal human hematopoiesis was studied by constitutively expressing theHOXA5 cDNA in CD34+ and CD34+CD38− cells from bone marrow and cord blood. By using retroviral vectors that contained both HOXA5and a cell surface marker gene, pure populations of progenitors that expressed the transgene were obtained for analysis of differentiation patterns. Based on both immunophenotypic and morphological analysis of cultures from transduced CD34+ cells, HOXA5expression caused a significant shift toward myeloid differentiation and away from erythroid differentiation in comparison to CD34+ cells transduced with Control vectors (P= .001, n = 15 for immunophenotypic analysis; and P < .0001, n = 19 for morphological analysis). Transduction of more primitive progenitors (CD34+CD38− cells) resulted in a significantly greater effect on differentiation than did transduction of the largely committed CD34+ population (P = .006 for difference between HOXA5 effect on CD34+v CD34+CD38−cells). Erythroid progenitors (burst-forming unit-erythroid [BFU-E]) were significantly decreased in frequency among progenitors transduced with the HOXA5 vector (P = .016, n = 7), with no reduction in total CFU numbers. Clonal analysis of single cells transduced with HOXA5 or control vectors (cultured in erythroid culture conditions) showed that HOXA5expression prevented erythroid differentiation and produced clones with a preponderance of undifferentiated blasts. These studies show that constitutive expression of HOXA5 inhibits human erythropoiesis and promotes myelopoiesis. The reciprocal inhibition of erythropoiesis and promotion of myelopoiesis in the absence of any demonstrable effect on proliferation suggests that HOXA5 diverts differentiation at a mulitpotent progenitor stage away from the erythroid toward the myeloid pathway.

THE PLURIPOTENT hematopoietic stem cell is capable of either self-renewal or of generation of committed progenitors that give rise to mature blood elements. How this decision is controlled at the molecular level remains an unanswered question. However, a coded pattern of gene expression must exist that carries out the maturation program. Understanding the nature of the underlying pattern of gene expression and how it arises will provide a better understanding as to how hematopoietic lineage commitment occurs.

An increasing body of work suggests that the homeobox family of genes may be at least one component of the coded pattern of gene expression regulating hematopoiesis.1 Homeobox genes were originally described as important regulators of embryogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster, through the study of homeotic mutations whereby one body part was replaced by another.2-5 Homeobox genes have subsequently been identified in numerous species spanning the evolutionary spectrum.6-8 The hallmark of all homeobox genes is a 183-nucleotide stretch of sequence called the homeobox, which encodes a highly conserved 61-amino acid homeodomain whose helix-turn-helix tertiary structure binds DNA.9 Through this DNA-binding activity, the homeodomain proteins function as transcription factors and thereby regulate differentiation through positive and negative regulation of gene expression.4,6,10In mice and humans, the homeobox genes located within four specific clusters on different chromosomes are referred to as the HOXfamily.11

Early evidence for a role of homeobox genes in blood cell differentiation came from the observation that these genes are involved in the chromosomal abnormalities associated with certain leukemias.12 It has also been shown that HOX genes are expressed in somewhat lineage-specific patterns in cell lines and bone marrow and that experimental manipulation of these expression patterns can influence the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic cell lines.13-21 We have recently identified the HOXA5 homeobox gene in a screen of HOX genes expressed early during myelopoiesis.21 Using an antisense approach, we demonstrated that reducing HOXA5 expression in human bone marrow cells potentiates erythroid development while reducing granulocytic/monocytic cell development.21Conversely, ectopic expression of HOXA5 inhibited the erythroid development of the myeloid cell line, K562.21 In experiments reported here, we enforced expression of HOXA5 in normal human hematopoietic progenitor cells by transducing CD34+ and CD34+CD38− cells with a retroviral vector containing the HOXA5 cDNA. In these studies, we show that ectopic expression of HOXA5 results in a shift toward myeloid differentiation at the expense of erythroid differentiation. These data support the hypothesis that HOXA5functions as an important regulator of lineage commitment, specifically, determination of myeloid versus erythroid fates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of retroviral vectors.

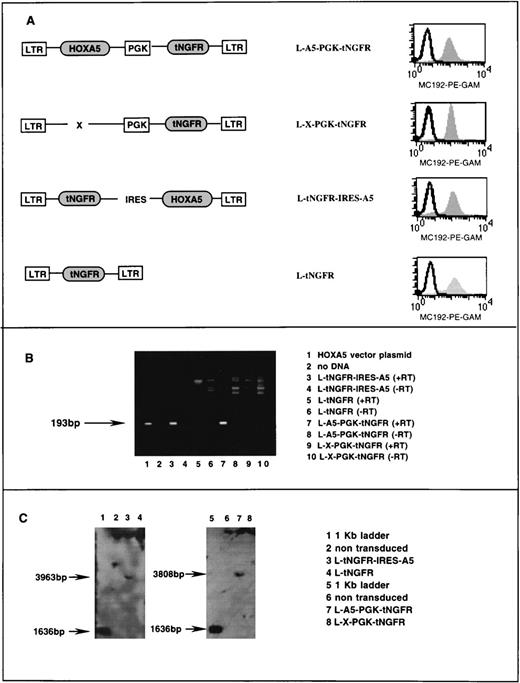

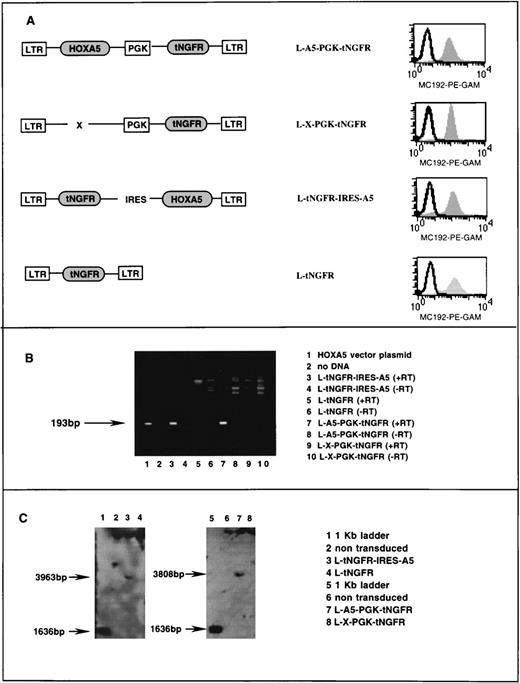

Two HOXA5-containing vectors (and their paired controls) were constructed. Each incorporated the rat low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR; p75) as a cell surface marker gene. The NGFR cDNA was truncated to remove the cytoplasmic tail to produce the inactivated tNGFR.22 In the first pair of constructs, the SV40 promoter and neoR gene were removed from the LXSN vector23 and replaced with the murine phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter,24 followed by the tNGFR cDNA to make the control vector L-X-PGK-tNGFR. The human HOXA5 cDNA, generated as described previously,21 was cloned into L-X-PGK-tNGFR to make the vector L-A5-PGK-tNGFR. The HOXA5 cDNA encodes a protein that is truncated after the homeodomain: there is no difference in the activities of this construct and the full-length clone.21

In the second construct, the human HOXA5 cDNA was cloned downstream of the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) from the encephalomyocarditis virus (ECMV)25 to align the ATG start codon of the HOXA5 cDNA in-frame with that from the IRES. tNGFR was cloned into the LN vector plasmid23 replacing the neoR gene to make the control vector L-tNGFR. The IRES-HOXA5 fusion was then cloned downstream of tNGFR to produce the vector L-tNGFR-IRES-A5.

Stable high titer vector producing clones of the cell line PG13 were generated for each of the two HOXA5 vectors and their respective negative control vectors (Fig1A). PG13 is a murine fibroblast cell line that expresses the Gibbon ape leukemia virus (GALV) envelope protein. HOXA5 expression in PG13 producer clones was assessed by reverse polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as follows. RNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s guidelines using the RNA STAT-60 kit (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX) and reverse transcribed to cDNA (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). The cDNA was then subjected to 35 cycles of PCR as follows: 94°C (1 minute), 60°C (1 minute), and 72°C (1.5 minutes). HOXA5 primers sequences were 5′ primer (5′CGCCGGCAGCACCCACATCAG3′) and 3′ primer (5′TTCCGGGCCGCCTATGTTGT3′), which amplified a 193-bp product (Fig 1B). On each sample, mRNA for the gene GAPDH was also determined by reverse PCR as a positive control to confirm the presence of mRNA and successful reverse transcription. Primers for the GAPDH cDNA were as follows: 5′ primer (5′TGATGACATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAG3′) and 3′ primer (5′TCCTTGGAGGCCATGTGGGCCAT3′), which amplify a 240-bp fragment of GAPDH cDNA. Twenty-five cycles of PCR at 94°C (2 minutes), 55°C (1.5 minutes), and 72°C (1.5 minutes) were performed for PCR of GAPDH.

Characterization of retroviral vectors. (A) Schematic diagram of HOXA5 and control vectors with FACS analysis of tNGFR expression (MC192-PE-GAM fluorescence) in corresponding PG13 vector-producing clones. (B) Ethidium bromide gel showing products of reverse PCR from RNA extracted from vector producing PG13 clones (lanes 3 through 10). The 193-bp HOXA5product is detected in lane 1 (a positive control using vector plasmid) and lanes 3 and 4, showing that HOXA5 expression is present in PG13 clones containing HOXA5 vectors and not in PG13 clones with control vectors. (+/−RT, reverse transcriptase added/not added). (C) Southern blot analyses of 293A cells transduced with vectors shown, after digestion of DNA with EcoR5, which cuts at points 3′ and 5′ to the HOXA5 cDNA, and probing with HOXA5 cDNA.

Characterization of retroviral vectors. (A) Schematic diagram of HOXA5 and control vectors with FACS analysis of tNGFR expression (MC192-PE-GAM fluorescence) in corresponding PG13 vector-producing clones. (B) Ethidium bromide gel showing products of reverse PCR from RNA extracted from vector producing PG13 clones (lanes 3 through 10). The 193-bp HOXA5product is detected in lane 1 (a positive control using vector plasmid) and lanes 3 and 4, showing that HOXA5 expression is present in PG13 clones containing HOXA5 vectors and not in PG13 clones with control vectors. (+/−RT, reverse transcriptase added/not added). (C) Southern blot analyses of 293A cells transduced with vectors shown, after digestion of DNA with EcoR5, which cuts at points 3′ and 5′ to the HOXA5 cDNA, and probing with HOXA5 cDNA.

To ensure that no splicing or rearrangement of the vector had occurred during packaging, Southern blot analysis was performed on 293A cells (a human kidney cell line) that had been transduced with supernatants containing the two HOXA5-containing vectors and the two control vectors. DNA was extracted from the 293A cells selected posttransduction by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for tNGFR expression. DNA was digested with theEcoR5 restriction enzyme that cleaves 3′ and 5′ of the HOXA5 cDNA at bp 387 and 4195 in the vector L-A5-PGK-tNGFR (providing a 3,808-bp fragment including HOXA5) and at bp 213 and 4176 in the vector L-tNGFR-IRES-A5 (providing a 3,963-bp fragment including HOXA5). Digested DNA was run on a 1% agarose gel, transferred to nylon, and probed with an 800-bp fragment onHOXA5 (Fig 1C).

Isolation of target progenitors.

CD34+ cells were isolated from cord blood and bone marrow acquired from healthy normal donors according to guidelines from the Committee of Clinical Investigation (CCI) at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA). Mononuclear cells were first isolated from fresh samples by density centrifugation using Ficoll-hypaque (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). CD34+ cells were then isolated from the mononuclear cells using a MiniMacs column (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). In some experiments, CD34+CD38− cells were isolated by incubating the CD34+ enriched population with CD34-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (HPCA2; Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems [BDIS], San Jose, CA) and CD38-phycoerythrin (PE) (leu-17; BDIS) and isolating the more primitive CD34+CD38− cells on the FACSVantage (BDIS) as previously described.26

Retroviral transduction of progenitors.

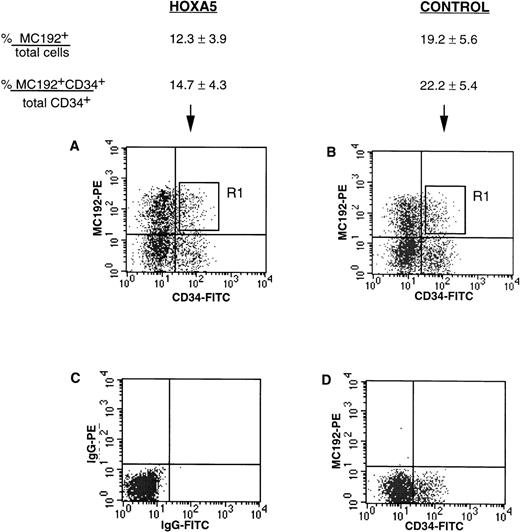

CD34+ or CD34+CD38− cells were incubated with viral supernatant for up to 4 days in transduction medium (Iscove’s modified Dulbecco medium [IMDM; GIBCO BRL], 5% fetal calf serum [FCS], 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA], 2-mercapoethanol, 10−6 mol/L hydrocortisone, penicillin/streptomycin, and glutamine with 5 ng/mL interleukin-3 [IL-3], 3.3 ng/mL IL-6, and 25 ng/mL Steel factor [SF]). Progenitor cells were cultured during transduction on plates coated with the recombinant human fibronectin fragment CH-296 (Retronectin; Takara, Otsu, Shiga, Japan). Twenty-four hours after final transduction, cells were incubated with 5 μL MC192 antibody (Oncogene Research Products, Cambridge, MA), which binds to tNGFR, followed by 5 μL of 1:20 PE-goat antimouse (GAM; Caltag, Burlingame, CA) and CD34-FITC. CD34+MC192+ cells were then isolated by FACS for culture and further analysis.

Cultures of transduced cells.

HOXA5 and control transduced CD34+ cells that expressed tNGFR were cultured in 25-cm vent cap flasks (Costar, Cambridge, MA) on human irradiated allogeneic bone marrow stroma in myeloid conditions, ie, long-term bone marrow culture (LTBMC) medium (IMDM, 30% FCS, 1% BSA, 2-mercapoethanol, 10−6 mol/L hydrocortisone, penicillin/streptomycin, and glutamine) with 5 ng/mL IL-3, 3.3 ng/mL IL-6, 25 ng/mL SF, 2 U/mL erythropoietin (EPO), and 50 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF); or in erythroid conditions, ie, LTBMC medium with IL-3, IL-6, SF, and EPO (no GM-CSF). Cultures were fed twice weekly with fresh medium. After 2 to 4 weeks of culture, nonadherent and adherent cells were analyzed by immunophenotype and morphology.

Clonal analysis of single CD34+tNGFR+ cells was performed in liquid and semisolid cultures as follows. Single CD34+tNGFR+ cells were either isolated by FACS and cultured in 96-well plates (Falcon, BD Labware, Lincoln Park, NJ) on irradiated stroma in erythroid conditions or plated immediately after transduction in duplicates or quadruplicates in semisolid medium (1.3% methylcellulose, IMDM, 30% FCS, 1% BSA, 2-ME 10−6 mol/L hydrocortisone, penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine, 10 ng/mL IL-3, 3.3 ng/mL IL-6, and 50 ng/mL SF). EPO (2 U/mL) was added once to the methylcellulose cultures between days 4 and 7. Colony-forming unit-cells (CFU-C), ie, colony-forming units–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM), colony-forming units–granulocyte erythroid macrophage megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM), and burst-forming unit-erythroid (BFU-E) were enumerated after 14 days.

Immunophenotypic analysis.

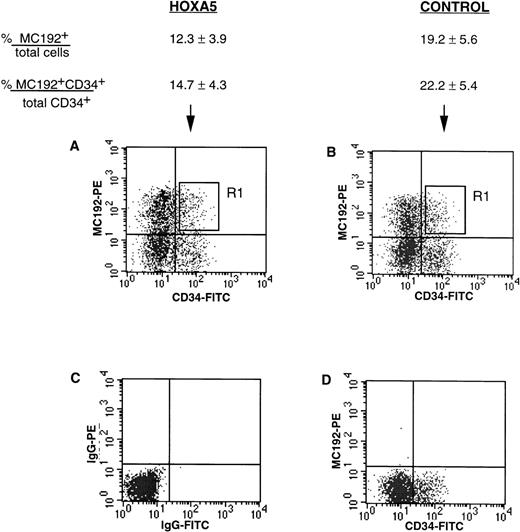

Cultures generated from bulk transduced cells were harvested, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA), and incubated with 20 μL glycophorin-FITC (Coulter Immunotech, Miami, FL) and 20 μL CD11b-PE (leu 15; BDIS). FITC and PE isotype controls (Coulter Immunotech) and mock (nontransduced) cells were used to define positive and negative quadrants (Fig 2). The immunophenotype of cultures was analyzed on a FACSVantage with CellQuest software (BDIS).

tNGFR expression after transduction of CD34+ progenitors with HOXA5 and control vectors. Numbers shown are the percentage of total cells expressing tNGFR (%MC192+/total cells) and the percentage of CD34+ cells expressing tNGFR (%MC192+CD34+/total CD34+cells) from 12 experiments (mean ± SEM). (A) and (B) show typical FACS profiles of cultures 24 hours after transduction with either theHOXA5 vector or control vector, respectively. The R1 gate was used to isolate MC192+CD34+ cells for further culture and analysis. (C) Isotype control. (D) Mock (nontransduced) control.

tNGFR expression after transduction of CD34+ progenitors with HOXA5 and control vectors. Numbers shown are the percentage of total cells expressing tNGFR (%MC192+/total cells) and the percentage of CD34+ cells expressing tNGFR (%MC192+CD34+/total CD34+cells) from 12 experiments (mean ± SEM). (A) and (B) show typical FACS profiles of cultures 24 hours after transduction with either theHOXA5 vector or control vector, respectively. The R1 gate was used to isolate MC192+CD34+ cells for further culture and analysis. (C) Isotype control. (D) Mock (nontransduced) control.

Morphologic analysis.

Cultures of transduced cells in bulk and clones of single cells were harvested and cytospin slides were prepared and stained with Wright-Giemsa. Differential counts were performed on at least 100 cells per slide noting the number of undifferentiated blasts, myeloid lineage cells (promyelocytes, myelocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages), and erythroid lineage cells (basophilic pronormoblasts, polychromatophilic normoblasts, and orthochromic normoblasts).

RESULTS

Retroviral vectors expressing HOXA5.

Retroviral vectors were used to establish transduction and constitutive expression of HOXA5 in human hematopoietic progenitors. Two different Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMuLV)-based vector backbones were used in these studies. Both vector backbones incorporated the inactive marker gene tNGFR that can be detected by FACS on the surface of transduced cells using the monoclonal antibody MC192. In the first vector (L-A5-PGK-tNGFR), HOXA5 was expressed from the MoMuLV LTR and tNGFR was expressed from an internal PGK promoter (Fig 1A). The second vector (L-tNGFR-IRES-A5) used an IRES to express both tNGFR andHOXA5 from the MoMuLV LTR. tNGFR expression was similar in PG13 producer fibroblasts expressing the two HOXA5 vectors and their respective control vectors (L-X-PGK-tNGFR and L-tNGFR; Fig 1A). Reverse PCR of RNA extracted from PG13 clones demonstrated HOXA5message in L-A5-PGK-tNGFR and L-tNGFR-IRES-A5 clones with noHOXA5 expression in the two control producer clones (Fig 1B). Southern blot analysis of 293A cells transduced with each vector confirmed that no splicing or rearrangement of vectors had occurred during packaging (Fig 1C).

Transduction of CD34+ cells with HOXA5vectors.

CD34+ cells were isolated from cord blood and bone marrow to 75% to 99% purity using two passes through the MiniMacs column. Freshly isolated CD34+ enriched cells analyzed at day 0 showed CD11b expression in 1.3% to 6.9% of cells and glycophorin expression in less than 1% cells. CD34+ cells were transduced with supernatant containing either HOXA5 vectors or control vectors. The levels of transduction with the HOXA5 and control vectors as measured by tNGFR expression (%MC192+) are shown in Fig 2. Twenty-four to 48 hours after transduction, cells coexpressing CD34 and tNGFR were isolated by FACS using the R1 gate shown in Fig 2 and placed onto irradiated human stroma for long-term culture in either erythroid conditions (IL-3, IL-6, SF, and EPO) or myeloid conditions (IL-3, IL-6, SF, EPO, and GM-CSF).

Immunophenotype of long-term cultures.

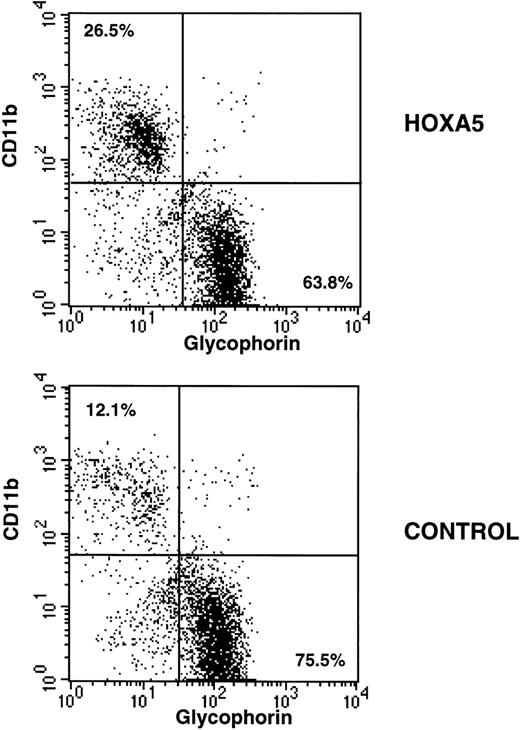

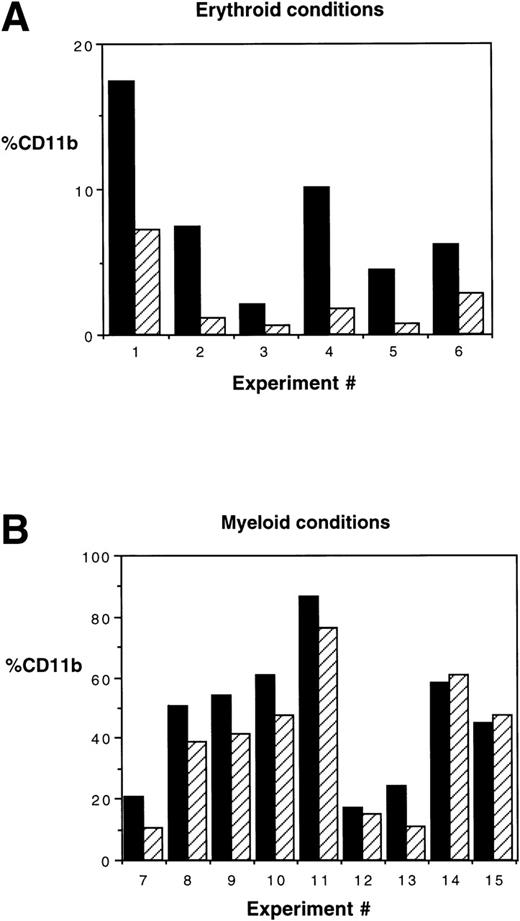

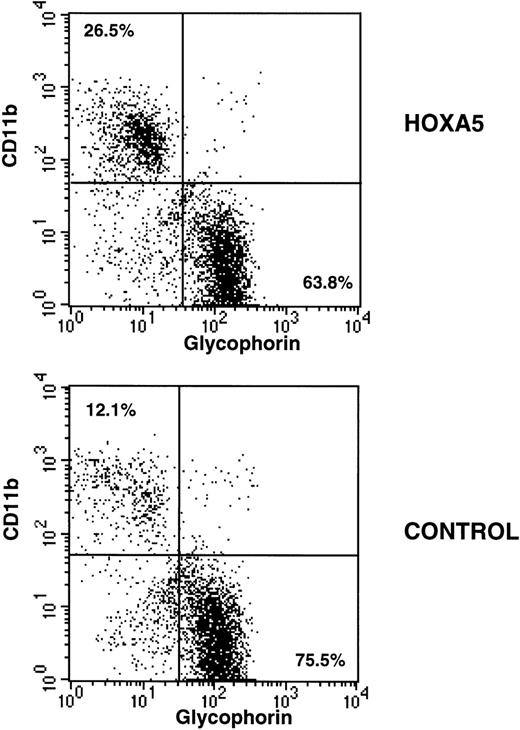

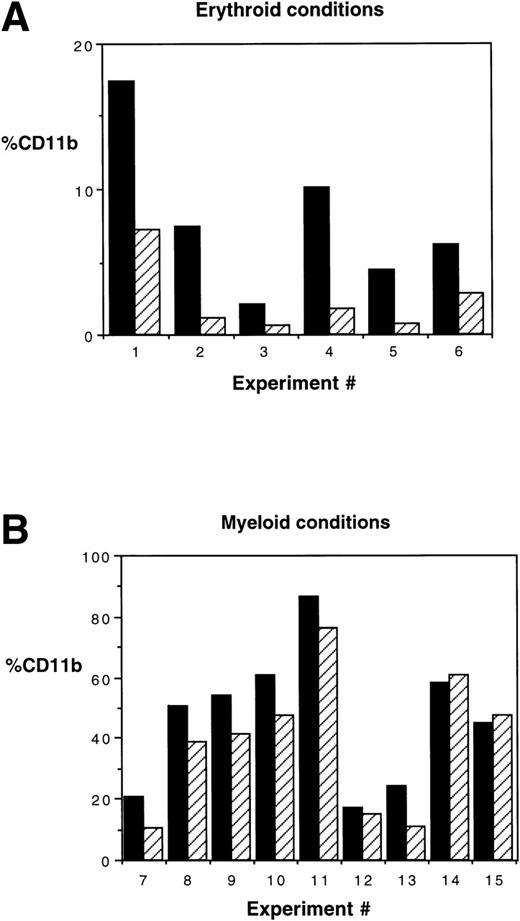

After 2 to 4 weeks of culture, cells were harvested, incubated with glycophorin-FITC (to assay erythroid differentiation) and CD11b-PE (to assay myeloid differentiation), and analyzed by FACS. As expected, CD11b expression was higher and glycophorin expression was lower in myeloid culture conditions compared with erythroid culture conditions. However, HOXA5 expression caused a shift toward myeloid and away from erythroid differentiation relative to control cultures irrespective of culture conditions (Fig 3). The frequency of CD11b+ cells was significantly increased in the HOXA5 transduced cultures compared with cultures of control transduced cells (Fig 4; P= .001 by Wilcoxon Rank test, n = 15). The increase in CD11b expression was accompanied by an equivalent decrease in glycophorin. The frequency of cells expressing neither CD11b nor glycophorin (ie, CD33negglycophorinneg cells) was not significantly different in cultures from HOXA5 and control transduced cells. The number of total cells in HOXA5 and control cultures was not different. The same effect on CD11b and glycophorin expression was seen whether cells were transduced with L-A5-PGK-tNGFR or with L-tNGFR-IRES-A5, demonstrating that the effect on differentiation was specific to HOXA5 expression rather than an uncharacterized artifact specific to the vector itself. Thus,HOXA5 expression in CD34+ progenitors caused a shift toward myelopoiesis at the expense of erythropoiesis.

Immunophenotypic analysis of HOXA5 and control cultures initiated with MC192+CD34+ cells. Nonadherent cells from 4-week-old cultures were harvested and incubated with CD11b-PE and glycophorin-FITC to measure myeloid and erythroid differentiation, respectively. HOXA5 transduction increased CD11b and decreased glycophorin expression relative to control transduction. The percentages of cells in the two quadrants are shown.

Immunophenotypic analysis of HOXA5 and control cultures initiated with MC192+CD34+ cells. Nonadherent cells from 4-week-old cultures were harvested and incubated with CD11b-PE and glycophorin-FITC to measure myeloid and erythroid differentiation, respectively. HOXA5 transduction increased CD11b and decreased glycophorin expression relative to control transduction. The percentages of cells in the two quadrants are shown.

CD11b expression is increased in HOXA5-transduced cultures. (A) In 6 of a total of 6 experiments in which MC192+CD34+ cells were cultured in erythroid conditions (P = .03 by Wilcoxon Rank test) and (B) 6 of 9 experiments cultured in myeloid conditions, HOXA5increased the frequency of cells expressing CD11b (P = .009). (▪) HOX A5; (▨) control.

CD11b expression is increased in HOXA5-transduced cultures. (A) In 6 of a total of 6 experiments in which MC192+CD34+ cells were cultured in erythroid conditions (P = .03 by Wilcoxon Rank test) and (B) 6 of 9 experiments cultured in myeloid conditions, HOXA5increased the frequency of cells expressing CD11b (P = .009). (▪) HOX A5; (▨) control.

Morphologic analysis of lineage differentiation.

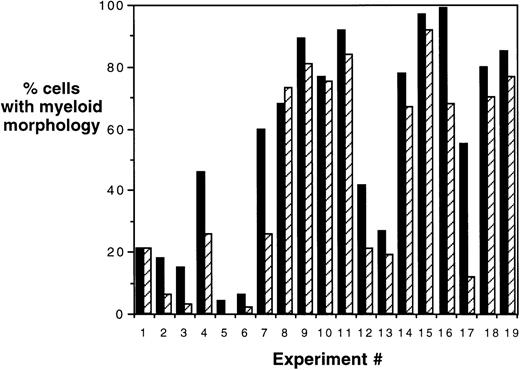

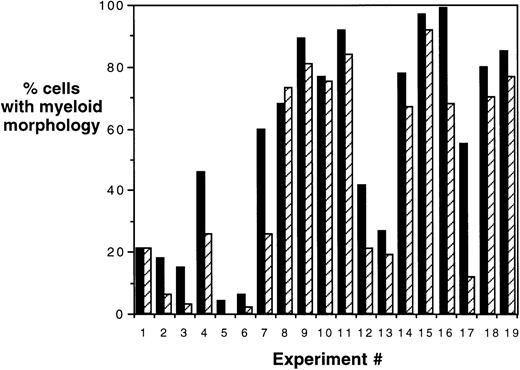

To confirm the immunophenotypic shift in differentiation patterns induced by HOXA5 expression, HOXA5 and control cultures were also analyzed morphologically using cytospin preparations from the total nonadherent cell population (Fig 5). Again, HOXA5 expression significantly increased the proportion of cells with myeloid morphology and decreased cells with erythroid morphology (P < .0001, using Wilcoxon Rank Sign test to analyze the difference in myeloid morphology between HOXA5 and control cultures, n = 19).

Morphologic analysis of HOXA5 and control cultures. Percentages of cells of myeloid and erythroid lineage were determined morphologically using cytospin preparations of cultures. In 17 of total of 19 experiments, HOXA5-transduced cultures contained a higher frequency of myeloid cells than control cultures (P = .0001). (▪) HOX A5; (▨) control.

Morphologic analysis of HOXA5 and control cultures. Percentages of cells of myeloid and erythroid lineage were determined morphologically using cytospin preparations of cultures. In 17 of total of 19 experiments, HOXA5-transduced cultures contained a higher frequency of myeloid cells than control cultures (P = .0001). (▪) HOX A5; (▨) control.

In addition, to confirm the lineage specificity of the above-noted immunophenotypic analyses, CD11b+ and glycophorin+ cells were isolated from culture by FACS and examined morphologically using cytospin preparations and Wright Giemsa staining. CD11b+ sorted populations contained 76.7% ± 2.8% myeloid cells, 18.6% ± 3.0% undifferentiated blasts, and 8.9% ± 2.5% pronormoblasts (n = 9). Glycophorin+ sorted populations contained 96.4% ± 1.5% erythroid cells, 5.3% ± 2.2% undifferentiated blasts, and 0.2% ± 0.1% myeloid cells (n = 15). Thus, CD11b and glycophorin expression correlated closely with cell morphology within each culture.

HOXA5 expression in CD34+CD38− cells.

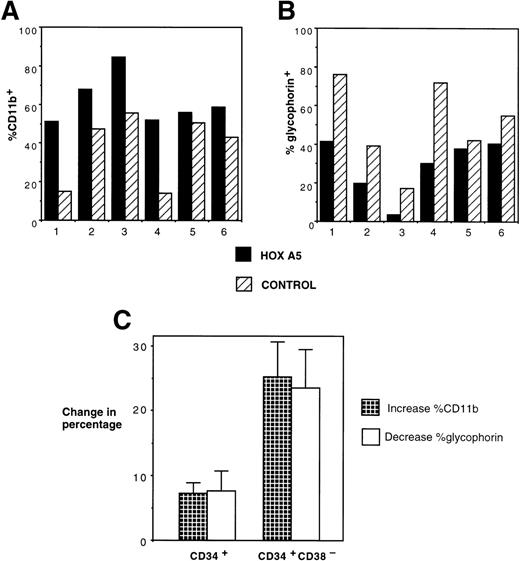

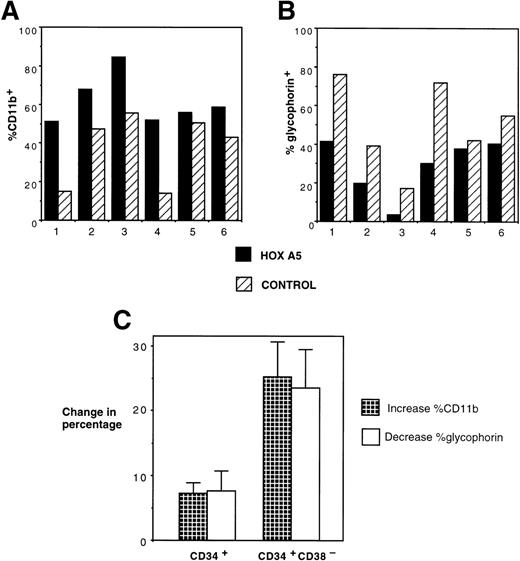

The effect of inducing HOXA5 expression in CD34+cells produced reproducible but relatively modest differences in the proportions of myeloid and erythroid cells in the experiments described to date. Reasoning that the variability seen in the experiments may be due to the high frequency of CD34+ progenitors already committed to erythroid or myeloid lineage before transduction, we next explored whether HOXA5 expression in a more primitive and uncommitted progenitor population might cause a greater effect on differentiation. In 6 of 6 experiments targeting CD34+CD38− cells, HOXA5 again caused a shift toward myelopoiesis and away from erythropoiesis relative to control cultures (Fig 6A and B). The effect on differentiation pattern was significantly greater when CD34+CD38− cells were transduced than when CD34+ cells were transduced (24.0% ± 5.1%v 4.2% ± 3.1% increase in CD11b+ cells and 22.4% ± 5.6% v 4.6% ± 3.5% decrease in glycophorin expression in CD34+CD38− [n = 6] and CD34+ cultures [n = 15], respectively; P = .006 by Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test; Fig 6C).

Effects of HOXA5 overexpression in CD34+CD38− cells. (A) CD11b and (B) glycophorin expression from 4-week-old cultures of CD34+CD38− cells transduced with eitherHOXA5 or control vectors (n = 6 independent experiments). (C) The effect of HOXA5 expression on CD11b and glycophorin expression is greater when CD34+CD38− cells are transduced than when CD34+ cells are transduced (P = .006). Shown are the mean ± SEM of the increase in the percentage of CD11b+ cells (% HOXA5 − % control) and the decrease in the percentage of glycophorin+ cells (% control − % HOXA5; n = 6 CD34+CD38− experiments and n = 15 CD34+ experiments).

Effects of HOXA5 overexpression in CD34+CD38− cells. (A) CD11b and (B) glycophorin expression from 4-week-old cultures of CD34+CD38− cells transduced with eitherHOXA5 or control vectors (n = 6 independent experiments). (C) The effect of HOXA5 expression on CD11b and glycophorin expression is greater when CD34+CD38− cells are transduced than when CD34+ cells are transduced (P = .006). Shown are the mean ± SEM of the increase in the percentage of CD11b+ cells (% HOXA5 − % control) and the decrease in the percentage of glycophorin+ cells (% control − % HOXA5; n = 6 CD34+CD38− experiments and n = 15 CD34+ experiments).

Clonal analysis of HOXA5-transduced progenitors.

We next studied the effect of HOXA5 expression on progenitor differentiation at a clonal level. Erythroid culture conditions (IL-3, IL-6, SF, and EPO) were chosen to determine to what extentHOXA5 could induce myeloid differentiation in the absence of GM-CSF. CD34+ cells were transduced on days 0 and 1 on fibronectin with either L-A5-PGK-tNGFR or the control vector L-X-PGK-tNGFR. On day 4, CD34+MC192+ cells were analyzed either in semisolid medium for CFU-C content or deposited by FACS as single cells in each well of a 96-well plate prepared with irradiated stroma for clonal analysis.

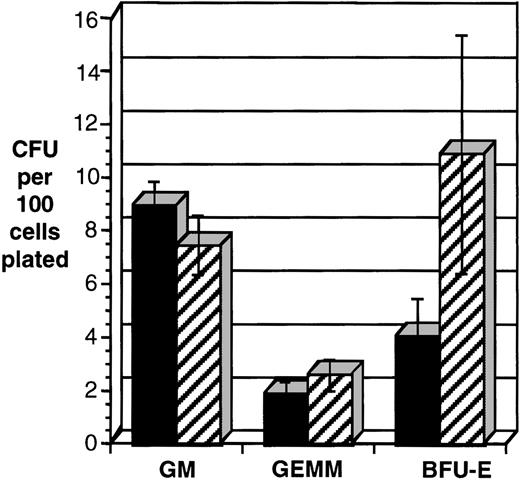

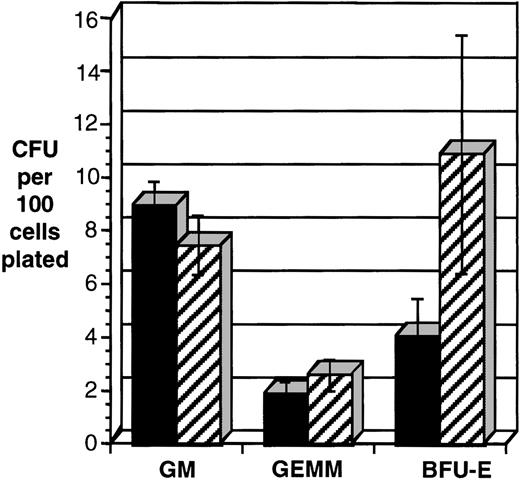

The frequency of erythroid progenitors (BFU-E) was consistently decreased in CD34+ cells transduced with HOXA5(P = .016, n = 7; Fig 7). Colonies containing both erythroid and myeloid cells (CFU-GEMM) were also reduced in the HOXA5-transduced cells and pure myeloid colonies (CFU-GM) were increased, but the results did not reach statistical significance. It is noteworthy that the total number of CFU-C (erythroid and myeloid) was not significantly different betweenHOXA5- and control-transduced cultures.

HOXA5 expression in CD34+ cells decreases the frequency of erythroid progenitors (BFU-E). CD34+tNGFR+ cells were isolated after transduction and immediately plated in semisolid medium to enumerate and characterize CFU-C content. Shown are data from seven independent experiments. *P < .016. (▪) HOX A5; (▨) control.

HOXA5 expression in CD34+ cells decreases the frequency of erythroid progenitors (BFU-E). CD34+tNGFR+ cells were isolated after transduction and immediately plated in semisolid medium to enumerate and characterize CFU-C content. Shown are data from seven independent experiments. *P < .016. (▪) HOX A5; (▨) control.

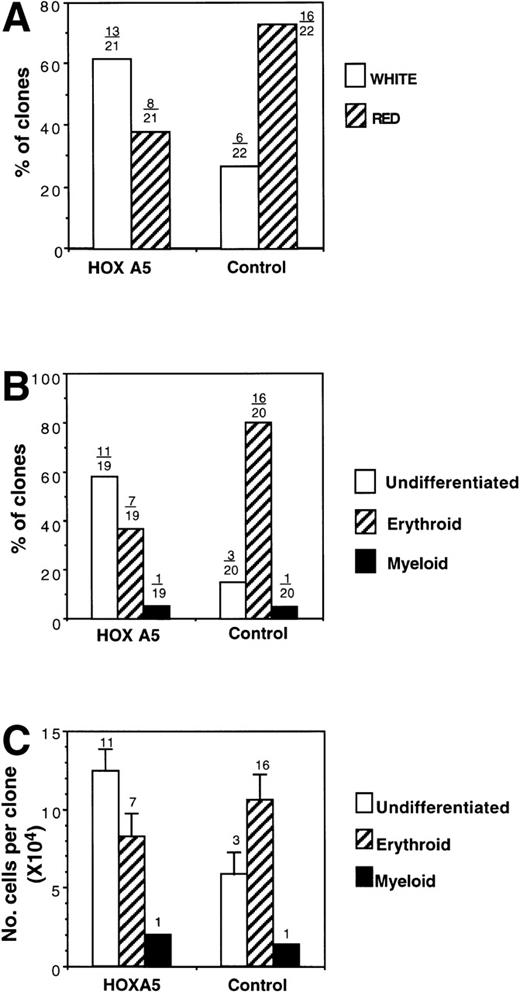

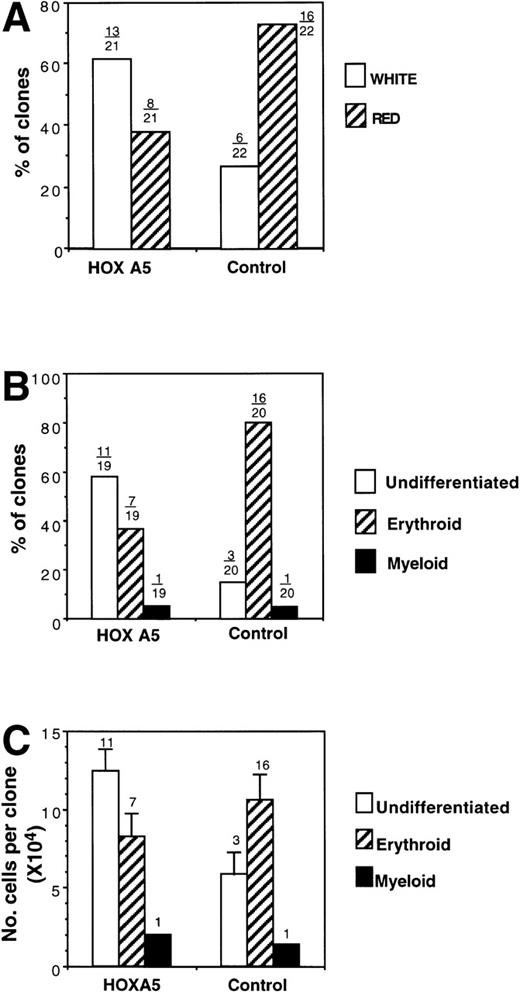

Similar results were obtained in the assay of single clonogenic CD34+ cells cocultured with stroma in liquid culture with identical growth factors. Total cloning efficiency was not altered byHOXA5 expression; after 14 days of erythroid culture, a total of 21 HOXA5-transduced clones and 22 control-transduced clones were visible. The color of each clone was reported as red or white by direct visualization of the plates. Eight of 21 (38.1%) of theHOXA5 clones were red (hemoglobinized), compared with 16 of 22 (72.3%) of control clones (Fig 8A). Nineteen HOXA5 clones and 20 control clones contained sufficient cells for analysis of morphology (performed by a second observer who was blinded to the particular vector used in transduction and to the color previously noted for each clone; Fig 8B). One clone in each of the HOXA5 and control groups contained myeloid cells (both had been scored as white). Most (11 of 19 [57.9%]) of theHOXA5 clones contained only undifferentiated blasts. In contrast, 3 of 20 (15%) control clones contained only undifferentiated blasts, and most (16/20 [80%]) of the control clones contained a mixture of blasts and mature erythroid precursors (polychromatophilic normoblasts and orthochromic normoblasts). These two analyses of erythroid differentiation (clone color and cell morphology) were validated by the strong correlation of the analyses within each clone studied by independent, blinded observers. All red clones contained at least some mature erythroid precursors (a mean of 57% ± 6.5% polychromatophilic normoblasts and orthochromic normoblasts were found in each red clone). White clones, in contrast, consisted almost entirely (94.7% ± 2.8%) of undifferentiated blasts, with only 2 of the total 14 white clones containing any mature erythroid precursors. Thus, by two independent but strongly correlated analyses, clones expressing HOXA5 contained cells at a more morphologically primitive stage than control clones. It cannot be determined from these studies whether the morphologically undifferentiated blasts were committed at a molecular level to either the myeloid or erythroid lineage. However, it can be concluded thatHOXA5 was not sufficient to increase differentiation to a mature myeloid phenotype in the absence of GMCSF, but appeared at least to inhibit erythroid differentiation.

Analysis of clones derived from single MC192+CD34+ cells after transduction withHOXA5 or control vectors. (A) Percentage of clones scored as red (hemoglobinized) or white (nonhemoglobinized) by direct visualization. Over each bar is shown the actual number of clones of each color over the total analyzed. (B) The percentage of clones scored by morphology as undifferentiated, erythroid, or myeloid. (C) Cell proliferation of clones according to cell morphology. The number of clones analyzed is shown over each bar.

Analysis of clones derived from single MC192+CD34+ cells after transduction withHOXA5 or control vectors. (A) Percentage of clones scored as red (hemoglobinized) or white (nonhemoglobinized) by direct visualization. Over each bar is shown the actual number of clones of each color over the total analyzed. (B) The percentage of clones scored by morphology as undifferentiated, erythroid, or myeloid. (C) Cell proliferation of clones according to cell morphology. The number of clones analyzed is shown over each bar.

Finally, the cell number within each clone was measured to determine whether the inhibition of erythroid differentiation was associated with inhibition of proliferation. HOXA5 and control clones with mature erythroid morphology had similar cell proliferation. In contrast, cell proliferation of undifferentiated clones was higher in the HOXA5 group than in the control group, suggesting that the inhibition of erythropoiesis with HOXA5 was not accompanied by inhibition of total cell proliferation and in fact may be associated with increased cell proliferation (Fig 8C).

DISCUSSION

HOXA5 is one of several HOX genes implicated in regulating hematopoietic decision-making. Studies have shownHOXA5 expression to be restricted to cells of the myelomonocytic lineage and absent in cells of the erythroid lineage.17,27 It has also been observed that the level ofHOXA5 message in a subpopulation of human CD34+cells displaying erythroid potential is lower than that found in more primitive cells or CD34+ cells displaying granulocytic potential.20 In other work, we have shown that theHOXA5 gene is expressed early in myeloid development and that manipulation of this gene’s expression in normal hematopoietic cells and cell lines results in a significant alteration in the relative levels of erythroid and myeloid cell development.21 Considered together, these studies suggest that HOXA5 is expressed in a stage- and lineage-specific manner and that this pattern of expression may influence the fate of the developing blood cell.

In our current work, we have extended previous studies by expressingHOXA5 in normal human hematopoietic progenitor cells, using retroviral transduction, in an attempt to further define the role for this gene during blood cell development. Ectopic expression ofHOXA5 in human CD34+ hematopoietic cells resulted in a reproducible increase in myelopoiesis in the culture conditions used, as measured by cell surface expression of CD11b and cell morphology. This increase in myelopoiesis was accompanied by an equivalent decrease in erythropoiesis, as measured by cell surface glycophorin expression and cell morphology. This reciprocal effect suggests that HOXA5 is influencing lineage commitment events at a common myeloid/erythroid progenitor stage. Transduction ofHOXA5 into the more primitive CD34+CD38− cells resulted in a more pronounced shift from erythroid to myeloid development, further suggesting that HOXA5 functions at a crucial early stage in lineage commitment. These findings correlate well with our previous work showing that inhibition of HOXA5 expression in human CD34+ cells resulted in increased erythropoiesis and decreased myelopoiesis. Together, these data support a role forHOXA5 as part of the molecular mechanism that directs a multipotent progenitor cell towards myeloid versus erythroid fates. In this role, erythroid lineage commitment and development would require downregulation of HOXA5 expression, whereas myeloid development requires and is potentiated by HOXA5.

Shifting lineage commitment by manipulating the expression of a singleHox gene has been observed previously. Thorsteinsdottir et al28 transduced murine bone marrow cells withHoxA10. Clonogenic assays showed a significant increase in megakaryocytic colonies, coupled to an inhibition of monocyte/macrophage colony formation, supporting the notion that normal hematopoiesis requires the precise and coordinated control of severalHox genes.

In the experiments reported here, there were no differences in the levels of proliferation of committed myeloid or erythroid progenitors transduced with HOXA5, suggesting that the proliferation of cells already committed to these lineages is refractory to the effects of HOXA5 expression. However, clones transduced withHOXA5 that remained undifferentiated in vitro displayed over twice the level of proliferation as undifferentiated clones containing the control vector. These data indicate that the inhibition of erythropoiesis seen in the HOXA5-transduced cells is not caused by the reduced proliferation of an erythroid-committed progenitor, but rather, appears to result in a molecular block of erythroid maturation. Equally intriguing, these data indicate that HOXA5 may play a role in regulating the self-renewal and/or proliferation of progenitor cells.

Such an effect on proliferation has been observed in similar experiments in which primitive murine bone marrow cells have been transduced to ectopically express Hox genes. Perkins and Cory29 demonstrated that HoxB8-transduced murine bone marrow could generate immortalized myeloid cell lines in the presence of high amounts of IL-3. Transplantation of theHoxB8-expressing marrow produced an acute leukemia in recipient mice. Sauvageau et al30 transplanted mice withHoxB4-transduced bone marrow cells, resulting in mice that exhibited a normal peripheral blood count but showed a 50- to 100-fold expansion of stem cell numbers. When HoxB3 was expressed in murine bone marrow, the numbers of myeloid progenitors in the marrow increased, and the mice eventually developed a myeloproliferative disorder.31 Based on these observations, it has been postulated that the temporal pattern of Hox gene expression follows blood cell lineage commitment; a large number of highly expressed Hox genes are present in early uncommitted progenitors, and lineage commitment is characterized by a restriction in the number and levels of HOX genes expressed in committed progenitors and mature cells.32 33 Our data further support this model, because it appears that by enforcing expression ofHOXA5 at a certain early stage of hematopoietic development, the cell is maintained in an uncommitted and highly proliferative state.

Because the precise downstream effectors of the HOX genes remain largely undefined, explaining how ectopic expression ofHOXA5 produces the observed phenotype is difficult. One possible explanation arises from the evidence for the existence of a system of transcriptional cross-regulation between hox proteins and the promoter elements of other homeobox genes.34,35 For instance, Lobe35 demonstrated that exogenous expression ofHoxA5 activated the expression of numerous endogenousHox genes, and HoxA5 has been shown to bind to its own promoter. Therefore, enforced expression of human HOXA5 may alter the expression of other HOX genes. Additionally, the hox proteins heterodimerize with a non-hox family of homeodomain-containing proteins called Pbx.36-38 The formation of this heterodimer pair results in altered binding specificity and affinity for target sequences.38 39Consequently, ectopic expression of HOXA5 may serve to titrate Pbx proteins away from the hox partners normally found during hematopoiesis, thereby altering the expression of numerous downstream genes.

This is the first report describing the experimental overexpression of a homeobox gene in normal human hematopoietic progenitor cells. A full understanding of how HOX genes regulate human hematopoiesis requires similar studies with more members of this gene family, both singly and in combination with each other, and the discovery of specific downstream effectors for these genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are very grateful to Lora Barsky for technical assistance with flow cytometry, Karen Pepper for vector production, Earl Leonard for biostatistical analysis, and Kaiser Permanente Sunset Hospital for collection of cord blood.

Supported by National Institutes of Health SCOR Grant No. HL54850.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Gay M. Crooks, MD, Division of Research Immunology/BMT, MS#62, Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, 4650 Sunset Blvd LA, CA 90027.