Jak3 is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase that associates with the common chain of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor and is involved in the function of the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15. Mice deficient in Jak3 have few T and B cells, and no natural killer cells. Herein we show that the myeloid lineages in these mice are also affected by the loss of Jak3. Mice lacking Jak3 exhibit splenomegaly by 4 months of age. Peripheral blood smears show an increase in the number of neutrophils and cells of the monocytic lineage. Flow cytometry of splenocytes and peripheral blood show a significant increase in FcγRII/III(FcγR)/Mac-1, FcγR/Gr-1, and FcγR/F4/80 double-positive cells in −/− and +/− mice compared to wild-type mice, consistent with an expansion of cells of the myeloid lineages. In addition, as the mice age, F4/80 and CD3 positive mononuclear cells infiltrate the kidneys, lungs, and liver of these mice. When Jak3−/− mice are crossed with a transgenic mouse expressing Jak3 in the T and NK cell compartments, the splenomegaly and myeloid expansion are accentuated. These data correlate with the constitutive activation of T cells in the periphery as the transgenic cells lose their expression of Jak3 with age. However, when Jak3−/− mice are crossed with RAG-1–deficient animals, no splenomegaly or myeloid expansion is apparent. These results indicate that the loss of Jak3 in the T-cell compartment drives the expansion of the myeloid lineages.

HEMATOPOIESIS is controlled by a variety of cytokines, many of which signal through receptors that belong to the hematopoietic receptor superfamily.1,2 This family of receptors lacks intrinsic enzymatic activity, but instead uses members of the Janus kinase (Jak) family of tyrosine kinases to activate and transmit a biological signal upon ligand binding. The Jak family of proteins consists of 4 known cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases (Jak1, Jak2, Jak3, and Tyk2) that are constitutively associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the receptors of this family. Upon ligand binding and oligomerization of receptor components, the associated Jaks are brought together, leading to transphosphorylation and activation. Upon activation, the Jaks phosphorylate tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domains of the receptors, leading to recruitment of src homology 2 (SH2) containing proteins to the phosphorylated receptors, such as members of the signal transducers and activators of transcription (Stat) family. The Jaks phosphorylate and activate these associated proteins, leading to downstream signals, such as transcriptional activation by the Stat proteins.1 2

Recently, Jak3 has been deleted by gene targeting in mice by several investigators.3-6 Jak3 associates with the common chain of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor (IL2Rγc), and is involved in the signal transduction of cytokine receptors that share this subunit, which include IL-2, -4, -7, -9, and -15.1,2Mice deficient in Jak3 exhibited a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) phenotype, similar to the phenotype observed in human patients with Jak3 deletions or mutations.7-10 The thymi of knockout mice contained approximately 0.5% to 10% of the normal number of cells. Despite the very low number of thymocytes, the CD4 and CD8 staining pattern in the thymus is relatively normal. The cellularity of the bone marrow was also similar between normal and knockout animals. However, there was a block in B-cell development at the pre-B stage in the bone marrow, with a decrease in both CD45R+/CD43− and CD45R+/IgM+ cells. The spleens were consistently smaller in young knockout animals, although total cell numbers steadily increased with age. The CD4/CD8 staining patterns in the spleen were relatively normal, but there was a large reduction in CD45R+/IgM+ cells in the spleen. Though immature B lymphocytes and mature T lymphocytes were present in the spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes, the cells functional responses were impaired. Responses of lymphocytes to LPS, PMA, ionomycin, concanavalin A, IL-2, IL-7, anti-CD3, and anti-CD28 alone or in combination were severely reduced or absent. In addition, there appears to be few or no natural killer cells or γ/δ T cells in the Jak3 knockout animals.4

In contrast to the dramatic defects in lymphocyte maturation observed in young Jak3 knockout animals, the myeloid lineages showed no apparent defects early in development. Blood smears showed normal numbers of monocytes and neutrophils, and spleens stained with Mac-1 appeared normal. Thus, although Jak3 is crucial for lymphoid development, it appeared dispensable or redundant for myeloid development. This was of interest because monocytes express Jak3 upon cytokine stimulation and respond to the cytokines whose receptors use the IL-2Rγcchain.11-15 Herein we describe defects in myelopoiesis in the Jak3 knockout animals that develop as the mice age. These defects include the development of severe splenomegaly, a significant increase in myeloid/premonocytic cells in the peripheral blood, spleen, and bone marrow, and invasion of peripheral organs with mononuclear cells. In addition, we show that this phenotype is accentuated when the development of Jak3-deficient T cells is rescued with the transgenic expression of Jak3 in the T-cell compartment. Furthermore, mice deficient in both Jak3 and RAG-1 do not exhibit splenomegaly and myelopoiesis, suggesting that Jak3-deficient T cells drive the expansion of the myeloid lineages, leading to splenomegaly and infiltration of organs with mononuclear cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The Jak3 knockout mice, and transgenic mice expressing Jak3 under the control of the proximal Lck promoter used in these studies, have been described previously.3 16 RAG-1–deficient mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were bred and kept in pathogen-free housing in accordance with Washington University School of Medicine animal care guidelines. Mice represented in this study were tested for common mouse pathogens and were deemed negative by pathology, culture, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

Tissue histology and peripheral blood analysis.

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma, St Louis, MO), embedded in paraffin (Baxter, McGaw Park, IL), and stained with hematoxylin/eosin. Peripheral blood analysis was performed on a Baker 9000 Coulter Counter (Serono Laboratories, Randolph, MA). Peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright-Geisma (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), and differential blood counts were reported as the mean cell count per 100 nucleated cells examined.

Cell preparation and flow cytometry analysis.

Splenocyte suspensions were prepared using frosted glass slides. Approximately 1 mL of total blood was obtained from each mouse by cardiac puncture after lethal anesthetic administration. Bone marrow cells were obtained from the femur and tibia of each mouse using 22-gauge needles and sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). All cell samples (1 × 106 cells) were first incubated with 5 μg of R-phycoerythrin- or fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated Fcγ receptor (FcγRII/III; PharMingen, San Diego, CA) antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C, and then counterstained for 30 minutes at 4°C with R-phycoerythrin or fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated antibodies to the following surface markers: CD3ε, CD4, CD8β chain, TCR α/β, CD90.2 (Thy1.2), Ly-6A/E (Sca-1), CD25 (IL-2Rα chain), H2Kk, Ly-6G (Gr-1), PK136 (NK1.1), (Mac-3), CD45R (B220), CD11b (Mac-1), L-selectin (PharMingen), and F4/80 (a gift from D. Link, Washington University School of Medicine). Samples were analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) after acquisition of 20,000 to 50,000 total cells per sample. All fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) scans depicted are representative results of 3 to 5 mice analyzed from each genotype group.

Immunohistochemistry.

Tissues were embedded in Tissue Freezing Media (Fisher), and 10-μm sections were cut, fixed in cold acetone, and air dried. Sections were incubated in blocking buffer consisting of PBS, 2% goat serum, and 1% mouse serum for 20 minutes. Sections were blocked with a commercial biotin blocking kit (Vector, Burlingame, CA), then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with biotinylated antibodies directed against CD3, Mac-1, and B220 (PharMingen) and F4/80 (Caltag, South San Francisco, CA) at dilutions of 1:25, 1:50, 1:50, and 1:50, respectively. Sections were washed for 15 minutes in PBS, then incubated with streptavadin/horseradish peroxidase (ABC reagent; Vector) for 30 minutes, washed for 15 minutes in PBS, developed with a diaminobenzidine substrate kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and counterstained with methyl green (Vector).

RESULTS

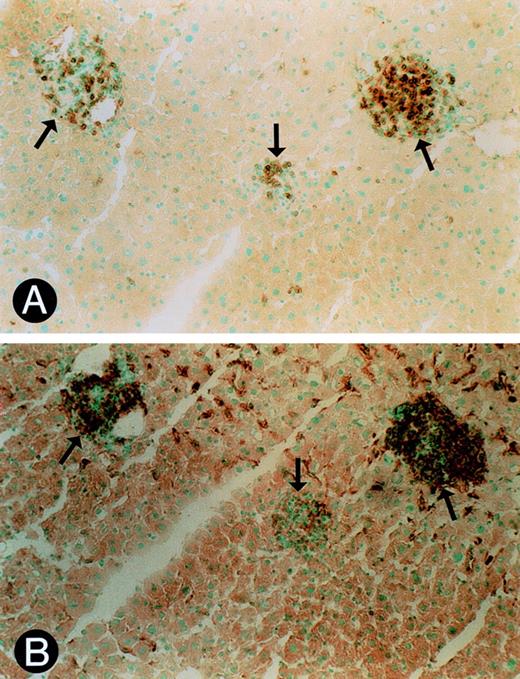

Upon further analysis of the Jak3 knockout mice (−/−), we observed that all mice 5 months or older exhibited severe splenomegaly (Fig 1A). Splenomegaly developed in knockout animals as early as 4 months of age, but not in heterozygous or wild-type littermates up to 12 months of age (data not shown). The general architecture of the spleen was severely disrupted in the −/− mice. The white pulp, with its characteristic lymphoid sheath surrounding a central artery, was replaced by a collection of large cells with euchromatic nuclei (Fig 1B). Immunohistochemistry showed that these cells stained positive for CD3 (data not shown). In addition, numerous megakaryocytes were apparent. Further histological examination of homozygous mice showed widespread organ infiltration of the lungs, kidneys, and liver with mononuclear cells (Fig 1C through E). Immunohistochemical staining of the tissues identified both F4/80- and CD3-positive cells in the infiltrates (Fig 2A and B).

Gross and microscopic examination of Jak3−/− mice. (A) Anatomy of spleens from wild-type (top), +/− (middle), and −/− (bottom) mice. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stain of spleen. Open arrow denotes expanded population of cells surrounding central artery. Closed arrow denotes lymphocytes scattered amongst red pulp (original magnification [OM] × 360). (C) H & E stain of Jak3−/− liver, showing portal infiltrates (OM × 360). (D) H & E stain of lung. Closed arrow denotes infiltrate around large vessels (OM × 360). (E) H & E stain of kidney. Open arrow identifies large vessel infiltrates. Closed arrow denotes emigrating lymphocytes (OM × 720). (F through I) Wright stain of peripheral blood, showing large cells of myelo/premonocytic lineage (OM × 1,080). (J and K) Wright stain of bone marrow smear (OM × 1,080).

Gross and microscopic examination of Jak3−/− mice. (A) Anatomy of spleens from wild-type (top), +/− (middle), and −/− (bottom) mice. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stain of spleen. Open arrow denotes expanded population of cells surrounding central artery. Closed arrow denotes lymphocytes scattered amongst red pulp (original magnification [OM] × 360). (C) H & E stain of Jak3−/− liver, showing portal infiltrates (OM × 360). (D) H & E stain of lung. Closed arrow denotes infiltrate around large vessels (OM × 360). (E) H & E stain of kidney. Open arrow identifies large vessel infiltrates. Closed arrow denotes emigrating lymphocytes (OM × 720). (F through I) Wright stain of peripheral blood, showing large cells of myelo/premonocytic lineage (OM × 1,080). (J and K) Wright stain of bone marrow smear (OM × 1,080).

Immunohistochemistry of cellular infiltrates. (A) Immunostaining of liver infiltrates with anti-CD3 antibody. Closed arrows identify positive staining cells in each infiltrate (OM × 720). (B) Immunostaining of liver infiltrates with anti-F4/80 antibody. Closed arrows identify positive staining cells in each infiltrate (OM × 720). Sections shown in (A) and (B) are serial sections.

Immunohistochemistry of cellular infiltrates. (A) Immunostaining of liver infiltrates with anti-CD3 antibody. Closed arrows identify positive staining cells in each infiltrate (OM × 720). (B) Immunostaining of liver infiltrates with anti-F4/80 antibody. Closed arrows identify positive staining cells in each infiltrate (OM × 720). Sections shown in (A) and (B) are serial sections.

Peripheral blood and bone marrow smears obtained from Jak3 −/− mice are shown in Fig 1F through K. There was an increase in myeloid progenitors and a slight decrease in erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow. Heterozygous and knockout mice exhibited significant neutrophilia, with higher numbers of both segmented and band neutrophils, and lymphopenia when compared with wild-type animals. Mature monocyte numbers were relatively similar in all 3 groups. Cells classified as myeloid/premonocytic were greatly increased in knockout animals, and slightly increased in the heterozygous mice (Table 1).

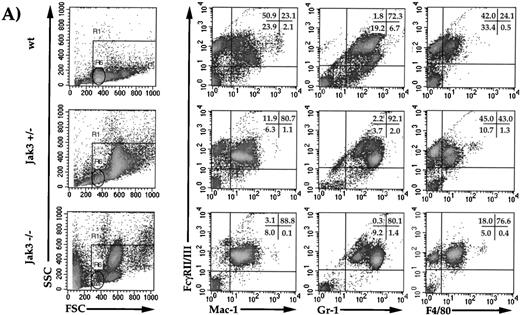

To further characterize the immature myeloid cells in the periphery of heterozygous and homozygous mice, whole-blood suspensions from 6- to 12-month-old mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for specific surface marker expression. As shown in Fig 3A, knockout and heterozygous mice showed a decrease in lymphocytes (gate R6, Fig 3A) compared with wild-type mice. There was a profound increase in large, granular cells in the peripheral blood from knockout and heterozygous animals compared with wild type, as evident by an increase in both side and forward scatter (cells outside of gate R6, Fig 3A). This large, granular cell population stained negative for the following markers: CD4, CD8, CD3ε, NK1.1, Mac-3, B220, Sca-1, CD25, TCR α/β, Thy 1.2, and CD90 (data not shown). When stained with antibodies against FcγR, Mac-1, F4/80, and Gr-1, Jak3+/− and −/− mice showed an increase in FcγR/Mac-1 double-positive cells, and a shift from FcγRhi/Gr-1med to FcγRmed/Gr-1hi–positive cells when compared with wild-type mice. When stained with FcγR and F4/80, there was an increase in FcγR/F4/80 double-positive cells in −/− animals compared with +/− and +/+ mice. The forward and side scatter profiles of the peripheral blood of −/− mice separated these large granular cells into two distint populations (Fig3B). One population showed greater granularity (SSC), a higher Gr-1 staining profile, and did not stain for F4/80 (gate R4), while the second population showed lower granularity, a lower Gr-1 staining profile, and positive staining for F4/80 (gate R5, Fig 3B). This indicates that cells of the R4 and R5 gates are of neutrophilic and monocytic lineages, respectively. When splenocytes from Jak3−/− and Jak3+/− mice were analyzed, a similar phenotype was observed (data not shown). Finally, bone marrow from Jak3−/− mice showed an increase of FcγR/Mac-1 (61.5%), FcγR/Gr-1 (69.6%), and c-Kit (11.3%) double-positive cells when compared with wild-type animals (46.9%, 66.4%, and 8.2%, respectively). In addition, there was a decrease in FcγR/Sca-1 double-positive cells in the homozygous animals compared with wild-type controls (3.8% v 8.8% respectively, data not shown).

Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface markers on wild-type, Jak3−/+, and Jak3−/− mice. (A) Dot plots of peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) depicting FSC and SSC scatter, R1 gates live cells from dead cells, and the R6 gate denotes the normal lymphocyte population. Density plots of PBLs stained with antibodies against FcγRII/III (vertical axis) versus Mac-1, Gr-1, and F4/80 (horizontal axes). (B) Dot plots of PBLs from Jak3−/− mice gating on large, granular cells (gate R4) and large, less granular cells (gate R5). Density plots of Jak3−/− PBLs show FcγRII/III, Gr-1, and F4/80 staining patterns of R4 and R5 populations.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface markers on wild-type, Jak3−/+, and Jak3−/− mice. (A) Dot plots of peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) depicting FSC and SSC scatter, R1 gates live cells from dead cells, and the R6 gate denotes the normal lymphocyte population. Density plots of PBLs stained with antibodies against FcγRII/III (vertical axis) versus Mac-1, Gr-1, and F4/80 (horizontal axes). (B) Dot plots of PBLs from Jak3−/− mice gating on large, granular cells (gate R4) and large, less granular cells (gate R5). Density plots of Jak3−/− PBLs show FcγRII/III, Gr-1, and F4/80 staining patterns of R4 and R5 populations.

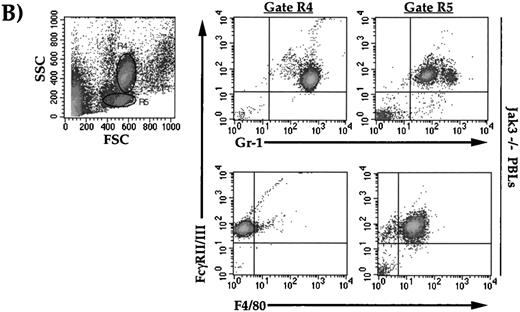

To investigate the cause of the myeloid expansion, Jak3−/− mice were bred with mice expressing Jak3 under the control of the proximal Lck promoter. These transgenic mice show normal early development of T cells and NK cells, but as the lymphocytes lose the expression of Jak3 with age in the periphery, they revert to the Jak3 deficient phenotype.16 When we examined transgenic Jak3−/− and Jak3+/− mice after 12 weeks of age, significant splenomegaly was apparent, with spleen sizes 2 to 3 times as large as age-matched Jak3−/− mice (data not shown). The lymphocytes in these mice had been developmentally restored, as shown by normal CD4 and CD8 flow cytometry profiles in the spleen and thymus (data not shown). When splenocytes from these mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for myeloid markers, it was apparent that Jak3−/− transgenic animals showed an expansion of large, granular cells, similar to that seen in Jak3−/− mice (Fig 4A, FSC and SSC). These mice also exhibited an increase of FcγR/Mac-1 and FcγR/F4/80 double-positive cells, and a shift from FcγRhi/Gr-1med– to FcγRmed/Gr-1hi–positive cells as compared with transgenic Jak3+/− littermates. We further characterized the CD4-positive lymphocytes from these transgenic Jak3−/− animals to determine if there was any evidence of activation. CD4-positive cells from transgenic Jak3−/− animals expressed very little L-selectin compared with transgenic Jak3+/− mice, indicating that these cells exhibited an activated phenotype (Fig4B). This is more clearly shown when CD4-positive cells are gated and analyzed for L-selectin expression (Fig 4B, histogram) To further investigate this phenotype, Jak3−/− mice were crossed with RAG-1–deficient animals. When 5-month-old Jak3/RAG-1–deficient mice were examined, no splenomegaly was apparent, and FACS profiles of the spleens of these mice were comparable to mice deficient in RAG-1 alone (data not shown).

Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface markers on transgenic (T) Jak3−/+ and Jak3−/− mice. Jak3−/− mice were crossed with a transgenic mouse expressing Jak3 under the control of the proximal Lck promoter, and splenocytes from transgenic Jak3+/− and Jak3−/− animals were analyzed as depicted in Fig 3. (A) Density plots of splenocytes depicting FSC and SSC scatter. Density plots of splenocytes stained with antibodies against FcγRII/III (vertical axis) versus Mac-1, Gr-1, and F4/80 (horizontal axes). (B) Density plots of splenocytes from transgenic Jak3+/− and Jak3−/− mice stained with antibodies against CD4 (vertical axis) and L-selectin (horizontal axis). Notice the lack of L-selectin high CD4-positive cells in the transgenic Jak3−/− animals. When CD4 cells are gated and analyzed for L-selectin expression, a shift of L-selectin high, CD4-positive cells in the Jak3+/− mice to L-selectin low, CD4-positive cells in the Jak3−/− mice is apparent.

Flow cytometric analysis of cell-surface markers on transgenic (T) Jak3−/+ and Jak3−/− mice. Jak3−/− mice were crossed with a transgenic mouse expressing Jak3 under the control of the proximal Lck promoter, and splenocytes from transgenic Jak3+/− and Jak3−/− animals were analyzed as depicted in Fig 3. (A) Density plots of splenocytes depicting FSC and SSC scatter. Density plots of splenocytes stained with antibodies against FcγRII/III (vertical axis) versus Mac-1, Gr-1, and F4/80 (horizontal axes). (B) Density plots of splenocytes from transgenic Jak3+/− and Jak3−/− mice stained with antibodies against CD4 (vertical axis) and L-selectin (horizontal axis). Notice the lack of L-selectin high CD4-positive cells in the transgenic Jak3−/− animals. When CD4 cells are gated and analyzed for L-selectin expression, a shift of L-selectin high, CD4-positive cells in the Jak3+/− mice to L-selectin low, CD4-positive cells in the Jak3−/− mice is apparent.

DISCUSSION

Here we describe a phenotype in the Jak3 knockout mice consistent with dysregulated hematopoiesis of the granulocyte and monocyte lineages. There was an increase in large, granular cells in the peripheral blood, spleen, and bone marrow which stained positive for the myeloid markers FcγRII/III, Mac-1, Gr-1, and F4/80, but did not stain for any lymphoid markers. Histological examination and flow cytometry of these cells suggests that both monocytic and neutrophilic lineages have expanded. This phenotype is not readily apparent at birth, but becomes apparent as the mice age. By 4 months of age the mice have severe splenomegaly, and by 5 months of age they have increased numbers of immature neutrophils and monocytes in the peripheral blood. Consistent with these findings, the first report of these knockout mice showed an increase of Mac-1–positive cells in the bone marrow and spleen of these mice as early as 4 weeks of age.3

There are several possible explanation to account for this phenotype. First, it is possible that other cellular components, such as natural killer (NK) cells, lacking in the Jak3−/− mice might be necessary to control myelopoiesis. SCID and RAG knockout mice, which are deficient in T and B cells, do not exhibit myeloid expansion. These mice, however, do have NK cells. Previous reports have suggested that NK cells and their products may play a role in controlling hematopoiesis.17-19 Mice deficient in both Jak3 and RAG-1, however, do not exhibit splenomegaly or altered myelopoiesis, suggesting that the loss of NK cells is not the causative agent. Secondly, the myeloid lineages themselves may require signals by cytokines whose receptors use Jak3 to negatively regulate their proliferation and expansion, and there is evidence for such a role for IL-7 and IL-4.20-24 Also, it is possible that the loss of Jak3 in the stromal cells of the bone marrow and spleen may be responsible for this phenotype, in that the loss of Jak3 in these stromal cells may affect colony-stimulating factor or other growth-factor production. In support of this, we have shown previously that endothelial cells can be induced to express Jak3,25and IL-4 has been shown to affect granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor production by endothelial cells.26 Finally, it is possible that the activated T cells that develop in the Jak3−/− animals drive the myeloid expansion. Recent evidence suggests that the expression of Jak3 is required for deletion of autoreactive T cells.16 Our findings support this notion that the Jak3-deficient T cells are the causative agent. When Jak3-deficient animals are crossed with RAG-1–deficient animals, no evidence of splenomegaly or myeloid expansion is detected. Furthermore, when peripheral T-cell numbers are increased by the transgenic expression of Jak3, the splenomegaly and myeloid expansion is significantly more severe. This correlates with the loss of the transgenic expression of Jak3 in the peripheral T cells, and their reversion to a Jak3-deficient, activated phenotype. Because the Jak3−/− transgenic animals have normal levels of Jak3 in the T cells of the thymus, these results suggest that the peripheral expression of Jak3 is critical for maintaining T cells in an unactivated state and preventing myeloid expansion. Furthermore, these studies indicate that B cells are not involved, because B-cell numbers are not increased in the Jak3−/− transgenic animals.

Because the deletion of Jak3 disrupts signaling through the receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, and IL-15, it is difficult to determine which cytokine or cytokines are responsible for this phenotype. Recent studies have suggested that a similar phenotype is observed in mice which are unable to respond to IL-2. IL-2Rα–deficient mice develop normally for the first 3 to 4 weeks, but then develop a polyclonal expansion of T and B cells with autoimmunity and inflammatory bowel disease, which is believed to occur due to a defect in activation-induced cell death.27 IL-2Rβ knockout animals exhibit a similar autoimmune syndrome.28 Interestingly, these animals develop a similar myeloproliferative disorder, with infiltrating myeloid cells in the liver, and large numbers of granulocytic and myeloid cells in the spleen. This phenotype was apparent at 4 weeks of age, and increased as the mice aged. Although necessary, we cannot say for certain if Jak3-deficient T cells are sufficient for this phenotype. It is possible that the autoreactive T cells initiate the myeloproliferative phenotype, while Jak3 expression in the myeloid compartment is required to halt this response. In support of this, depletion of T cells in IL-2Rβ knockout mice with antibody against CD4 did not correct the myeloproliferative disorder, while it did completely reverse the B-cell abnormalities observed in the IL-2Rβ knockout animals. Also, Jak3 is expressed at very low levels in resting monocytes, but is induced 12 to 24 hours after treatment with interferon-γ, lipopolysaccharide, and IL-2.11 The delayed, inducible expression of Jak3 may be involved in downregulating a myeloproliferative signal, and the inability to express Jak3 in the myeloid compartment may allow for this myeloproliferative signal to go unchecked.

The finding that Jak3-deficient T cells are capable of affecting myelopoiesis is surprising, because Jak3-deficient T cells are unable to proliferate or secrete cytokines under any conditions tested.3,5 16 However, these cells are not entirely nonfunctional because we provide strong evidence here that these cells are capable of inducing significant expansion of the myeloid lineages. Further studies are needed to clarify how these cells promote this phenotype, as well as to investigate the function of Jak3 in the myeloid compartment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are indebted to Daniel C. Thomis for his original work on the Jak3 knockout and transgenic mice. We also thank Dr Marie LaRegina, Niecey Hinkle, and Paula Klender at the Division of Comparative Medicine (Washington University) for their help in peripheral blood analysis, and Dan Link and Tim Ley for thoughtful discussion and critical review of this manuscript.

W.J.G. and J.W.V. contributed equally to this work.

Supported by Grants No. CA63417 (L.R.), 5T32HL07088 (W.J.G.), and MG44909 (L.E.F.) from the Public Health Service, by the American Cancer Society (L.J.B.) and the Life Sciences Research Foundation/Smith Kline Beecham Pharmaceuticals (D.D.C.), and by a National Institutes of Health Medical Scientist Training Program grant (to W.J.G. and J.W.V.). D.D.C. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Lee Ratner, MD, PhD, Washington University School of Medicine, Box 8069, 660 S Euclid Ave, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: lratner@imgate.wustl.edu.

![Fig. 1. Gross and microscopic examination of Jak3−/− mice. (A) Anatomy of spleens from wild-type (top), +/− (middle), and −/− (bottom) mice. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) stain of spleen. Open arrow denotes expanded population of cells surrounding central artery. Closed arrow denotes lymphocytes scattered amongst red pulp (original magnification [OM] × 360). (C) H & E stain of Jak3−/− liver, showing portal infiltrates (OM × 360). (D) H & E stain of lung. Closed arrow denotes infiltrate around large vessels (OM × 360). (E) H & E stain of kidney. Open arrow identifies large vessel infiltrates. Closed arrow denotes emigrating lymphocytes (OM × 720). (F through I) Wright stain of peripheral blood, showing large cells of myelo/premonocytic lineage (OM × 1,080). (J and K) Wright stain of bone marrow smear (OM × 1,080).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.932.415k30_932_939/5/m_blod415gro01z.jpeg?Expires=1767710176&Signature=jdS6aPO0UKl1Tt6bFZ~J0-L2a8HB01tM5qN9JP-myJAUSLm-9XGFjuGqB~X-pO2pgVRK90wshFLbRBTuWtnawwZyL~acbLx8A3sX3MzvXkLBLMw5I7eY~lLQCCdcgnt0IGgZ33RDwq74pyL2WBrZVly0sl25KEqCFKIlybWPowMdUgcl3aYGbxVKnaMxuxKHlf52X6pN-NBs2-f8gpTSpUz4vZbEYBhKgmOs0jVk4iGryABaXFcxZZkoOAGhhPSbxwF~4-pjkZX67u9lA4nB3opv7u~g1eEeOVXoPO1DU-kMsbjagjHmuvZyeeN9VJatuA~FgTPHpyIIekL6epBgrQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)