Abstract

Mature Plasmodium falciparum parasitized erythrocytes (PE) sequester from the circulation by adhering to microvascular endothelial cells. PE sequestration contributes directly to the virulence and severe pathology of falciparum malaria. The scavenger receptor, CD36, is a major host receptor for PE adherence. PE adhesion to CD36 is mediated by the malarial variant antigen, P. falciparumerythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), and particularly by its cysteine-rich interdomain region 1 (CIDR-1). Several peptides from the extended immunodominant domain of CD36 (residues 139-184), including CD36 139-155, CD36 145-171, CD36 146-164, and CD36 156-184 interfered with the CD36-PfEMP1 interaction. Each of these peptides affected binding at the low micromolar range in 2 independent assays. Two peptides, CD36 145-171 and CD36 156-184, specifically blocked PE adhesion to CD36 without affecting binding to the host receptor intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). Moreover, an adhesion blocking peptide from the ICAM-1 sequence inhibits the PfEMP1–ICAM-1 interaction without affecting adhesion to CD36. These results confirm earlier observations that PfEMP1 is also a receptor for ICAM-1. Thus, the region 139-184 and particularly the 146-164 or the 145-171 regions of CD36 form the adhesion region for P. falciparum PE. Adherence blocking peptides from this region may be useful for modeling the PE/PfEMP1 interaction with CD36 and for development of potential anti-adhesion therapeutics.

SEQUESTRATION OF MATURE stage parasitized erythrocytes (PE) is central for the survival and the pathology of P. falciparum parasites.1-4 Adherence of P. falciparum PE to endothelial cells in various blood vessels can result in local microvascular occlusion contributing directly to the pathology of P. falciparummalaria.1,5 6

Adherence of PE to endothelial cells is mediated by the binding of the infected erythrocyte to host receptors expressed on endothelial cells including CD36, thrombospondin (TSP), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and chondroitin sulfate A.2,7-10 Other molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), E-selectin, and CD31 mediate adherence of a minority of P. falciparumparasites.11-13 CD36 may play a predominant role in PE adherence, as almost all adherence positive P. falciparumstrains and isolates bind to CD36.13 There is a significant correlation between PE sequestration and expression of CD36 (and ICAM-1) in various organs and vascular endothelium.5,14Under flow conditions, which mimic in vivo blood flow, CD36 supports stable stationary adherence of PE, while ICAM-1 mediates PE rolling and adherence to TSP appears to be unstable.15 Recently, a recombinant protein from P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), named rC1-2, located in the first cysteine-rich interdomain region (CIDR-1) immediately after the first Duffy binding-like (DBL) domain was shown to mediate PE adherence to CD36.16 17

CD36 is an 88-kD glycoprotein scavenger receptor expressed on the surface of various cells including platelets, adipocytes, monocytes, macrophages, leukocytes, megakaryocytes, erythroblasts, melanoma cells, and endothelial cells.5,18,19 Several CD36 genes cloned from different organisms display high sequence conservation.20 In the last years, several other proteins were found to have sequence and structural homology with CD36. This includes the type B scavenger receptor SR-BI/CLA-1, the lysosomal protein LIMP II, 2 Drosophila proteins, and aCaenorhabditis elegans protein, all members of the CD36 gene family.20-22 CD36 is implicated in uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins (ox-LDL), long chain fatty acids, anionic phospholipids, phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils, and in signal transduction.23-30 CD36 can interact with a wide range of different molecules including ox-LDL, the extracellular matrix proteins collagen and TSP, and the malarial protein PfEMP1.17,20,27,29 31-35

Several anti-CD36 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) (8A6, OKM5, FA6-152, and 10/5) that block binding of ox-LDL and recognition of apoptotic neutrophils react with the CD36 immunodominant domain, defined by residues 155-183.33,34,36 These MoAbs also efficiently block adhesion of PE to human CD36.8 However, it was recently shown37 that the binding domain for ox-LDL resides elsewhere (residues 28-93) on CD36. Thus, these MoAbs block a function that resides outside the immunodominant region (155-183) of CD36, either by steric hindrance or by changing the conformation of CD36 required for binding. The binding domains for collagen and TSP were ascribed to the 415-427 and the 93-120 regions, respectively.31,32 Residues 139-155, located just before the immunodominant domain, were shown to induce a conformational change in TSP, which leads to higher affinity interaction between TSP and the 93-110 region of CD36.27 38

The inhibitory effect of MoAbs specific for the 155-184 region suggests that the binding domains for the inhibitory MoAbs and for PE overlap. However, PE bind to both human and mouse CD36, although only the human CD36 is recognized by the inhibitory MoAbs.39 40 This significant difference indicates that inhibitory MoAbs and infected erythrocytes recognize different residues of the CD36 multifunctional domain or that residues outside this region contribute significantly to the PE-CD36 interaction.

To study the region(s) of CD36 involved in binding of PfEMP1 and PE adhesion, we made a set of peptides from different regions of CD36 and tested their ability to inhibit the PfEMP1-CD36 interaction and to block PE adhesion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

Peptides.

CD36-derived peptides CD36 62-75 (residues 62-75), CD36 233-250 (residue 238 (Lys) was replaced by a Tyr residue), CD36 358-370, CD36 397-409, and CD36 413-426 (with an additional Tyr residue) were custom synthesized by Bio-Synthesis Inc, (Lewisville, TX). Peptides CD36 139-155 and CD36 93-110 were synthesized both by Neuros Corp (San Jose, CA) and by Affymax Research Institute (Santa Clara, CA). Peptides CD36 93-110C and CD36 C139-155 with additional terminal cysteines at the carboxyl- or amino-terminus, respectively, were purchased from Bachem California (Torrance, CA) and also synthesized at Affymax Research Institute. Peptides CD36 139-149, CD36 142-152, and CD36 146-155 were synthesized by SynPeP Corporation (Dublin, CA). A scrambled version of the CD36 139-155 was also synthesized, but was largely insoluble even at 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Peptides CD36 145-171, CD36 146-164, and CD36 156-184 were synthesized by the support facility, NIAID, NIH. The ICAM 15-20 was synthesized at Affymax Research Institute. The amino acid sequences of the peptides are described in Table 1. All peptides were synthesized by the Fmoc method, purified to homogeneity by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and confirmed structurally by mass spectrometry. Peptide concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Soluble receptors.

Soluble CD36 extracellular domain was obtained in the form of harvest supernatant (approximately 1 to 5 μg/mL) after phospholipase C treatment of cultured cells as described before.35 Soluble ICAM-1 extracellular domain carrying the Protein A Ig binding domain (ZZ-ICAM) was a gift from Dr Andrew Hutchinson (Glaxo-Wellcome, Stevange, UK).

Antibodies.

Affinity purification of surface radiolabeled PfEMP1.

PE were surface radioiodinated and sequentially extracted with triton X-100 (TX100) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as described.35 Inhibition of binding of PfEMP1 to sCD36 or ICAM-1 was as described.35 Briefly, 5 to 10 μL of PE SDS extracts were reconstituted in 1 mL of 25 mmol/L HEPES, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) 0.5% TX100 in RPMI-1640 (BM-T, binding medium containing TX100) at pH 6.7 for CD36 and pH 7.3 for ICAM-1. Peptides dissolved in DMSO were added to the appropriate concentration. DMSO was added to give a final concentration of 5% DMSO. The reconstituted SDS extracts were incubated, 16 hours at 4°C, with CD36-derived peptides or, 1 hour at 21°C, with peptide ICAM-1 15-20 followed by incubation, 3 hours at 21°C, with immobilized receptor, and processed as described.35

Affinity-purification of CD36 with immobilized recombinant fragments of PfEMP1.

Affinity-purification of CD36 with immobilized rC1-2 [1-179] (GST-fusion) was described earlier.17 Briefly, 25 μL of GammaBind Plus Sepharose beads (Pharmacia Biotech Inc, Piscataway, NJ) were precoated, 90 minutes 21°C, with 10 μg of MoAb 141 (anti-GST), then incubated with 2.5 μg of rC1-2 [1-179]. The coated beads were incubated 60 minutes at 21°C, with 450 μL of BM containing peptides and 5% DMSO final concentration. A total of 50 μLl of soluble CD36 (0.5 to 1 μg/mL) was added and incubated 2 hours at 21°C. The beads were washed twice with BM, once with BM without BSA, and solubilized in 40 μL of SDS sample buffer. One to 2.5-μL samples were fractionated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), immunoblotted, and probed with a 1:10,000 dilution of biotinylated MoAb 179 as primary antibody followed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson Immunoresearch Inc) at 1:5,000 dilution.

Densitometry.

Autoradiographs were scanned and individual bands were quantified after background subtraction using the NIH Image 1.61 standard program.

Cytoadherence microassay.

Adherence of PE to immobilized proteins was performed by standard methods.17,41,42 For ICAM-1 binding, plates were spotted with 50 μg/mL of rabbit IgG and incubated with 25 μg/mL of ZZ-ICAM. Blockade of PE adherence by the different peptides was tested by preincubating, 1 hour at 37°C, PE in BM media (0.2% BSA) containing peptides and 1% DMSO final concentration. PE were added to the spotted receptors, incubated, 1 hour at 37°C, washed 4 times with BM, fixed, stained, and counted.42

RESULTS

CD36 and ICAM-1–derived peptides inhibit the binding of PfEMP1 to CD36 and ICAM-1, respectively.

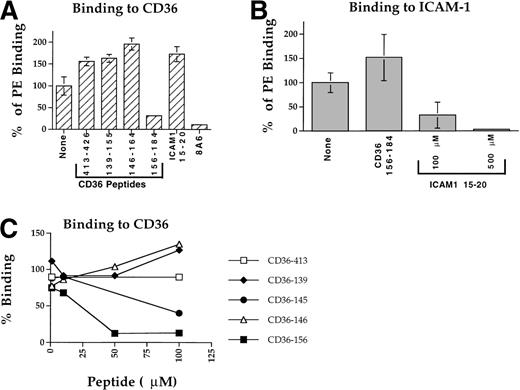

A panel of CD36 peptides27 (Fig1) were assayed at 500 μmol/L (300 μmol/L for peptide CD36 233-150) for their effects on the binding of 125I-PfEMP1 from the Malayan Camp (MC R+) strain (Fig 1A) and clone FCR3-C5 (Fig 1B) to CD36. Addition of DMSO (5%) had very little effect (Fig 1B), but in some of the assays, a 50% reduction in binding was observed (Fig 1A). Therefore, in each assay, the effect of each peptide was measured and compared with the binding of the DMSO control (100% binding). Peptides CD36 139-155, CD36 62-75, and CD36 233-250 blocked the CD36-PfEMP1 interaction by more than 50% for MC and 40% for FCR3-C5 (Fig 1). Peptide CD36 139-155 was the most active, affecting binding by 70% to 82%. Other peptides either increased binding or had very limited effect (up to 20%). The different effects of peptides on specific PfEMP1 bands is attributed to the variant sequence of different PfEMP1 molecules.17,41 43Three partial peptides from the 139-155 region (CD36 139-149, CD36 142-152, and CD36 145-155, Table 1) had no effect on binding (unpublished data).

CD36 peptides inhibit the binding of125I-PfEMP1 to CD36. TX100 insoluble material from surface iodinated PE was extracted with SDS (SDS extract) and reconstituted in RPMI containing 1% BSA and 0.5% TX100.35 Peptides dissolved in DMSO were added to the sample, incubated overnight, and allowed to bind to CD36-coated beads for 3 hours. The beads were washed 3 times and processed for SDS-PAGE as before.35 Peptides were tested at 500 μmol/L, except for peptide CD36 233-255, which was tested at 300 μmol/L. All samples except No DMSO, had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. The percent inhibition of binding from the DMSO control is indicated at the bottom of the figure. Negative numbers means higher binding than the DMSO control. (A) MC R+ SDS extract; (B) FCR3-C5 SDS extract. The percent inhibition of peptide CD36 358-370 with FCR3-C5 extract was calculated without the specific background subtraction.

CD36 peptides inhibit the binding of125I-PfEMP1 to CD36. TX100 insoluble material from surface iodinated PE was extracted with SDS (SDS extract) and reconstituted in RPMI containing 1% BSA and 0.5% TX100.35 Peptides dissolved in DMSO were added to the sample, incubated overnight, and allowed to bind to CD36-coated beads for 3 hours. The beads were washed 3 times and processed for SDS-PAGE as before.35 Peptides were tested at 500 μmol/L, except for peptide CD36 233-255, which was tested at 300 μmol/L. All samples except No DMSO, had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. The percent inhibition of binding from the DMSO control is indicated at the bottom of the figure. Negative numbers means higher binding than the DMSO control. (A) MC R+ SDS extract; (B) FCR3-C5 SDS extract. The percent inhibition of peptide CD36 358-370 with FCR3-C5 extract was calculated without the specific background subtraction.

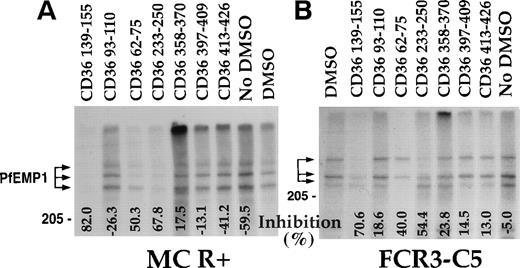

Dose response assays with the 3 active peptides demonstrated that peptides CD36 62-75 and CD36 233-250 were active only at high concentrations (250 to 300 μmol/L) and actually increased binding at concentrations of 100 μmol/L or lower (Fig 2A). Thus, the activity of these peptides may not be highly specific for the PfEMP1-CD36 interaction. On the other hand, peptide CD36 139-155 had an apparent 50% inhibition (IC50) of ≈ 5 μmol/L (Fig 2A and Table 2). The peptide had no effect on the binding of ItG-ICAM PfEMP1 to ICAM-1 (not shown), indicating that its blocking activity is specific for the PfEMP1-CD36 interaction. To verify these results, 3 preparations of peptide CD36 139-155 derived from independent sources were assayed and found to consistently block binding of PfEMP1 to CD36.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of binding of125I-PfEMP1 to CD36 and ICAM-1. (A) Inhibition of binding to CD36 using MC R+ SDS extract was performed as in Fig1. Peptide concentration is given in μmol/L. The concentration of peptide CD36 397-409 was 500 μmol/L. (B) Inhibition of binding to ICAM-1 using ItG-ICAM SDS extract was performed as in Fig 1, except that the peptides were preincubated with the extract for 1 hour at room temperature. Peptide concentration is given in μmol/L and all samples (except No DMSO) had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. The percent inhibition of binding from the DMSO control is indicated at the bottom of the figure.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of binding of125I-PfEMP1 to CD36 and ICAM-1. (A) Inhibition of binding to CD36 using MC R+ SDS extract was performed as in Fig1. Peptide concentration is given in μmol/L. The concentration of peptide CD36 397-409 was 500 μmol/L. (B) Inhibition of binding to ICAM-1 using ItG-ICAM SDS extract was performed as in Fig 1, except that the peptides were preincubated with the extract for 1 hour at room temperature. Peptide concentration is given in μmol/L and all samples (except No DMSO) had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. The percent inhibition of binding from the DMSO control is indicated at the bottom of the figure.

Peptide ICAM-1 15-20 blocks adherence of intact PE (ItG2-ICAM strain) to ICAM-1.44 This peptide also blocked the binding of ItG2-ICAM PfEMP1 to ICAM-1 at a concentration of 100 μmol/L or higher with an IC50 of about 200 μmol/L (Fig 2B). The peptide did not block the interaction of MC PfEMP1 with CD36 (not shown). These results are consistent with independent binding domains for CD36 and ICAM-1 on PfEMP1.35 45

CD36-derived peptides block binding of rC1-2 [1-179] to CD36.

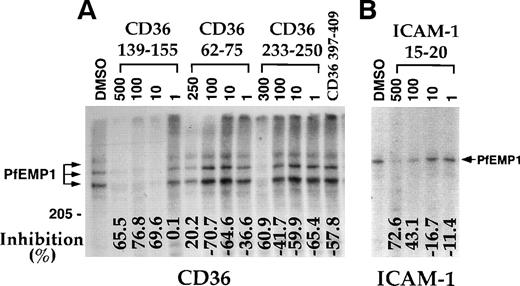

A region from the CIDR-1 domain of MC-PfEMP1, represented by the recombinant protein rC1-2, was recently demonstrated to bind CD36 and to mediate PE adherence to CD36.17 Peptide CD36 139-155 blocked the interaction of CD36 with rC1-2 [1-179] with apparent IC50 of about 2 μmol/L (Fig 3and Table 2). At 50 μmol/L, peptides CD36 62-75 and CD36 233-250, which blocked binding of PfEMP1 to CD36 at high concentrations (Fig 2), had little (23.1%) to no effect (6.3%) on this interaction compared with 78% to 92% inhibition with peptide CD36 139-155 (Fig 3). Peptides CD36 139-149 and CD36 142-152, but not peptide CD36-145-155, blocked the binding of CD36 to rC1-2 (1-179) (Fig 3A). Some of this activity may be attributed to the highly hydrophobic nature of the first 2 peptides. Also, these assays are not truly quantitative, but demonstrate the range of effective inhibition of binding of each peptide.

CD36 peptides inhibit the binding of rC1-2 [1-179] to CD36. Peptides were prepared in 0.45 mL of binding media pH 6.7 containing 1% BSA and 5% DMSO and microfuged for 5 minutes before addition to the coated beads to remove insoluble peptide material. Peptides were incubated, 1 hour at room temperature with beads coated with rC1-2 [1-179] before addition of sCD36. After 3 hours incubation, the beads were washed and solubilized for SDS-PAGE.17 The binding of CD36 was assayed by Western blot using biotinylated MoAb 179 recognizing a tag incorporated to the sequence of sCD36.17 All samples (except No DMSO) had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. Percent inhibition of binding (from the DMSO control) is indicated at the bottom of the figure. Negative numbers means higher binding than the DMSO control. (A) Various CD36-derived peptides tested at 50 μmol/L. (B) Concentration-dependent inhibition of binding of CD36 to rC1-2 [1-179]. Peptides concentration is in μmol/L. Peptide CD36 139-155 was largely insoluble at 100 μmol/L and peptide CD36 146-164 was only partially soluble at 50 μmol/L. In both cases, most of the peptide was removed by the centrifugation step resulting in low to no inhibition (data not shown).

CD36 peptides inhibit the binding of rC1-2 [1-179] to CD36. Peptides were prepared in 0.45 mL of binding media pH 6.7 containing 1% BSA and 5% DMSO and microfuged for 5 minutes before addition to the coated beads to remove insoluble peptide material. Peptides were incubated, 1 hour at room temperature with beads coated with rC1-2 [1-179] before addition of sCD36. After 3 hours incubation, the beads were washed and solubilized for SDS-PAGE.17 The binding of CD36 was assayed by Western blot using biotinylated MoAb 179 recognizing a tag incorporated to the sequence of sCD36.17 All samples (except No DMSO) had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. Percent inhibition of binding (from the DMSO control) is indicated at the bottom of the figure. Negative numbers means higher binding than the DMSO control. (A) Various CD36-derived peptides tested at 50 μmol/L. (B) Concentration-dependent inhibition of binding of CD36 to rC1-2 [1-179]. Peptides concentration is in μmol/L. Peptide CD36 139-155 was largely insoluble at 100 μmol/L and peptide CD36 146-164 was only partially soluble at 50 μmol/L. In both cases, most of the peptide was removed by the centrifugation step resulting in low to no inhibition (data not shown).

Earlier studies suggested that the adherence blocking MoAb OKM5 recognizes the 139-155 region of CD36.27 Human-mouse hybrids of CD36 demonstrated that OKM5, 15.2, and other adherence blocking MoAbs actually recognize the adjacent region (155-183) of CD36.39 Therefore, additional peptides from the 155-184 and 139-184 regions were synthesized (see Table 1) and measured for their effect on binding of CD36 to the rC1-2 [1-179] GST fusion protein (Fig 3 and Table 2). Peptides CD36 146-164 and CD36 156-184 inhibited the CD36-rC1-2 [1-179] interaction at 50 μmol/L (Fig 3A) and were active even at a concentration of 0.1 μmol/L (Fig 3B). Peptide CD36 156-184 was also active at 0.01 μmol/L (only partial inhibition), while peptide CD36 146-164 appeared to be inactive at this concentration (data not shown). Peptide CD36 145-171 inhibition profile for the rC1-2 [1-179]-CD36 interaction was similar to that of CD36 146-164 (not shown). Thus, peptides from both regions, CD36 139-155 and CD36 156-184, represent sites of CD36, which interact with the PE receptor, PfEMP1.

The inhibitory effect of different peptides is influenced by their solubility.

The relative solubility of the various peptides was determined by the appearance and the size of a precipitate after centrifugation. Although this does not give an accurate measurement of solubility and of the actual concentration of soluble material, it gives a good indication if a peptide is only partially or completely soluble at the conditions of each assay. Peptide CD36 156-184 was soluble even at high concentrations (>250 μmol/L). However, several of the active peptides, mainly CD36 139-155 and CD36 146-164, were not completely soluble at concentrations higher than 50 to 100 μmol/L, as large precipitates were observed and removed by centrifugation. This observation explains the reduction of inhibition associated with high peptide concentrations for some peptides (D. Baruch, unpublished observations). Peptide CD36 145-171 solubility was higher than CD36 146-164, but not as good as CD36 155-184. Thus, at the high μmol/L range, the actual final concentration of the peptide in the assay solution may be lower, depending on the relative solubility of the peptide in the assay solution. This is particularly important in blockade of adherence assays. In this assay, the amount of DMSO must be restricted to 1% (final) compared with 5% DMSO or 5% DMSO/0.5%TX100/0.1% SDS used in the affinity purification assays. Moreover, significantly higher peptide concentration is needed to block the interaction of the multivalant PE with CD36. Thus, marginally soluble peptides may not be soluble at the concentration required for blockade of PE adherence, although they may effectively block the PfEMP1-CD36 interaction. However, differences in the IC50(Table 2), measured at the low μmol/L range are not affected by peptide solubility and represent true differences in the inhibitory activity of the different peptides.

CD36 and ICAM-1–derived peptides block PE adhesion.

Peptide CD36 156-184 at a concentration of 100 μmol/L blocked PE adhesion to CD36 of strain A4ultra by more than 70% (Fig 4A), with an IC50 of about 25 μmol/L (Fig 4C and Table 2). Another peptide, CD36 145-171, with higher solubility than CD36 146-164 (but lower than CD36 156-184) blocked PE adhesion to CD36 with an IC50 of about 86 μmol/L (Fig 4C and Table 2). Other peptides tested, CD36 413-426, CD36 139-155, CD36 146-164, and ICAM-1 15-20 had no inhibitory effect on PE binding (Fig 4A). However, peptides CD36 139-155 and CD36 146-164 were only partially soluble at the 50 to 100 μmol/L concentration and failed to reach the high concentration necessary to block PE adhesion. This is particularly true for peptide CD36 139-155 that had much higher IC50 than the other peptides (Fig 3B and Table 2). The higher binding found with some of the peptides is attributed to the combined effect of both peptide and DMSO resulting in elevated adherence of PE or higher binding of PfEMP1 (see Figs 1 through 4 and D. Baruch, unpublished observation). In each case, the percent inhibition of adherence was calculated from the DMSO control (no peptide).

Blockade of PE adherence to immobilized CD36 and ICAM-1. PE from clone A4ultra were incubated for 1 hour in binding media containing the appropriate peptide and final concentration of 1% DMSO, then added to the spotted receptor for 1 hour and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are given as percent binding from the control (no peptide). (A) Blockade of adhesion to CD36 tested at 100 μmol/L. MoAb 8A6 was tested at 10 μg/mL. (B) Blockade of adherence to ICAM-1. Peptide CD36 156-184 was tested at 100 μmol/L, peptide ICAM-1 15-20 was tested at 100 and 500 μmol/L. (C) Concentration-dependent blockade of adherence to CD36. Peptide inhibition was tested at 1 to 100 μmol/L range as described in (A).

Blockade of PE adherence to immobilized CD36 and ICAM-1. PE from clone A4ultra were incubated for 1 hour in binding media containing the appropriate peptide and final concentration of 1% DMSO, then added to the spotted receptor for 1 hour and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Results are given as percent binding from the control (no peptide). (A) Blockade of adhesion to CD36 tested at 100 μmol/L. MoAb 8A6 was tested at 10 μg/mL. (B) Blockade of adherence to ICAM-1. Peptide CD36 156-184 was tested at 100 μmol/L, peptide ICAM-1 15-20 was tested at 100 and 500 μmol/L. (C) Concentration-dependent blockade of adherence to CD36. Peptide inhibition was tested at 1 to 100 μmol/L range as described in (A).

Peptide CD36 156-184 had no inhibitory effect on PE adherence to ICAM-1 (Fig 4B). The ICAM-1 15-20 peptide completely blocked adhesion to ICAM-1 at 500 μmol/L and more than 60% at 100 μmol/L (Fig 4B and Table 2) with an IC50 of about 97 μmol/L, but had no effect on PE adhesion to CD36 (Fig 4A). These results demonstrate that the activity of the CD36 peptides and in particular CD36 156-184 is specific for PE adherence to CD36 and that the ICAM-1 15-20 peptide was specific for PE adherence to ICAM-1 (Fig 4).

DISCUSSION

Binding to CD36 plays a significant role in adherence of P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes.2,13-15 Antibodies that are able to block this interaction, such as 8A6, 10/5, and OKM5, recognize a single immunodominant domain (155-183) in human CD36.39,40 However, the inhibitory MoAbs do not bind to mouse CD36 while PE do.40 The MoAbs also block the binding of ox-LDL residing well outside the immunodominant domain,37 indicating a possible conformational change in CD36 mediated by Ab binding. This suggests that the regions of CD36 recognized by PE and the inhibitory MoAbs may not be the same. Therefore, we tested peptides from the sequence of CD36 to identify the PE binding domain of CD36.

Three independent assays were applied to assess the ability of different peptides to block the PE or PfEMP1 interaction with CD36. We identified several peptides CD36 139-155, CD36 146-171, CD36 145-171, and CD36 156-184 to have blocking effect on binding to CD36 in 2 different assays. These peptides had no effect on binding to the host receptor ICAM-1, indicating that the inhibition is specific for CD36. These peptides derive from the extended immunodominant region of CD36 (139-183), as residues 139-155 are believed to contribute to the binding of the OKM5 and similar antibodies to CD36.27 39

Several other peptides CD36 62-75, CD36 233-250, CD36 139-149, and CD36 142-152 also gave partial blocking activity (Figs 1 and 3). However, these peptides were positive for inhibition only in 1 of the 3 assays used and were active at much higher concentrations (IC50>200 μmol/L) than the CD36 139-184 peptides (IC50 <5 μmol/L). In addition, none of these peptides blocked PE adhesion. Peptides CD36 97-110 and CD36 8-21 reported by Asch et al46to block PE adhesion did not show any inhibition in our assays (CD36 97-110) or are lacking (CD36 8-21) from the soluble CD36 used here. Nevertheless, the possibility that the above residues contribute to the PE interaction with CD36 cannot be excluded.

Attempts to define the minimal binding domain were partially successful. Both peptides CD36 145-171 and CD36 146-164 were active, although only CD36 145-171 was able to block PE adhesion. Our attempts were complicated by the lack of solubility of the different peptides. Apart from CD36 156-184 and ICAM-1 15-20, which were readily soluble in aqueous solution, other peptides were much less soluble and could not be properly tested at high concentrations required for efficient inhibition. This is especially true in the PE blockade of adhesion assay where the DMSO content is restricted to maximum of 1% (compare with 5% in other assays). However, it is clear that although peptide CD36 139-155 was active, it displayed a much lower inhibition than the other 3 peptides (Table 2). Thus, we submit that the CD36 binding domain for PfEMP1 and infected erythrocyte is located at residues 139-184 of CD36 and in particular residues 145-171 or residues 146-164.

The PfEMP1 region corresponding to the rC1-2 [1-179] fragment of the CIDR-1 domain display significant variability among var genes including those originated from CD36 adherent parasites.17 Variation in the sequence of the CD36 binding domain, CIDR-1, and in binding domains for other host receptors, may result in qualitative and quantitative differences in adhesion of individual PE expressing PfEMP1 variants. These variations are expected to play a significant role governing the specific organ (eg, lung, heart, brain, placenta etc) and site of sequestration of individual PE. For example, PE sequestered in placenta binds to chondroitin sulfate A, but not to CD36.47 Although alternative recognition of residues of CD36 is possible, it appears that infected erythrocytes recognize the same CD36 domain, regardless of their variant sequences. The recombinant protein rC1-2 [1-179] blocked adhesion of all antigenically variant CD36-adherent PE tested.17 Also, the adhesion of various P. falciparum strains is blocked by Abs to the immunodominant domain of CD36.8,17,40 The peptides tested here provide additional support for a single adhesion region. These peptides inhibit the PE/PfEMP1 interaction with CD36 of 3 different strains, known to express different CIDR-1 sequences.16 17

Peptides from the CD36 139-184 region may have an anti-adhesion therapeutic potential. However, the high concentration needed for effective blockade of adherence and the relative low solubility of these peptides must be improved significantly for any possible anti-adherence therapeutics. In addition, several functions of CD36 may reside in this region or are influenced by Ab binding to this region, including binding of Ox-LDL, binding of fatty acids, phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils, and signal transduction properties.20,25,33,34,37 Adhesion of PE to this region may cause local inhibition or activation of some of the CD36-dependent processes on endothelial cells. Individuals who lack CD36 expression on monocytes are at risk of developing anti-CD36 antibodies (anti-NaKa) directed against the 155-183 region.36 The finding that infected erythrocytes bind to the CD36 multifunctional immunodominant domain raises the question of the effect of PE sequestration on CD36-dependent functions. Malaria-infected erythrocytes were found to activate monocytes and platelets, presumably by binding to CD36.25 Injection of peptides from the CD36 139-184 region may also have some adverse effect. However, it is conceivable that only a brief treatment will be required to affect PE adhesion resulting in release of sequestrating parasites to the circulation, without any prolonged adverse effect on the host.

In summary, we identified the extended immunodominant multifunctional domain of CD36 (residues 139-184) as the PE binding domain and in particular residues 145-171 and 146-164. Peptides from this domain blocked PE adherence in vitro and may be of therapeutic value. These findings expand our knowledge about the molecular interactions between infected erythrocytes and CD36.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr John Barnwell for providing MoAb 8A6 and Andrew Hutchinson for the ZZ-ICAM-1 recombinant protein.

Supported by Affymax Research Institute and Grant No. (HRN-6001-A-00-2043-00) to R.J.H from the United States Agency for International Development Malaria Vaccine Development Program.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Dror I. Baruch, MD, Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, NIAID, NIH Bldg 4, Room B1-37, 4 Center Dr, MSC 0425, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: dbaruch@niaid.nih.gov.

![Fig. 3. CD36 peptides inhibit the binding of rC1-2 [1-179] to CD36. Peptides were prepared in 0.45 mL of binding media pH 6.7 containing 1% BSA and 5% DMSO and microfuged for 5 minutes before addition to the coated beads to remove insoluble peptide material. Peptides were incubated, 1 hour at room temperature with beads coated with rC1-2 [1-179] before addition of sCD36. After 3 hours incubation, the beads were washed and solubilized for SDS-PAGE.17 The binding of CD36 was assayed by Western blot using biotinylated MoAb 179 recognizing a tag incorporated to the sequence of sCD36.17 All samples (except No DMSO) had a 5% final concentration of DMSO. Percent inhibition of binding (from the DMSO control) is indicated at the bottom of the figure. Negative numbers means higher binding than the DMSO control. (A) Various CD36-derived peptides tested at 50 μmol/L. (B) Concentration-dependent inhibition of binding of CD36 to rC1-2 [1-179]. Peptides concentration is in μmol/L. Peptide CD36 139-155 was largely insoluble at 100 μmol/L and peptide CD36 146-164 was only partially soluble at 50 μmol/L. In both cases, most of the peptide was removed by the centrifugation step resulting in low to no inhibition (data not shown).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/6/10.1182_blood.v94.6.2121/5/m_blod41809003w.jpeg?Expires=1771002915&Signature=ITe2l5pBql4T99NCnGTYXeEJLW4iM1DCEfDOgyJWntCcsZVSNeVHEnICjlYxT1caxY2pUy90N5S4oiARK3b5TQAxooXdjmrZojSC~ApSKKdgUqxFOHjQRW-CwXM0vs4SlKspMN48ZrV~aWk4BEyqW0XTCT8edZpp-~UNyHduO0DVNbhYlQ04nKRj6Fu3GoT97AWnV39q6q5NZwFVw4kEmGyY8AyOhS6fqBVBlX44tf~k1UOVzZZjERBQncG37K0woNe5lcGq8u3D~OhnF9OkYlfV6Ns3uRsy8x~dAI4t6JZ9fjk3oRY7vWDPg8MzSbBXeGk0vaJvGBAokHyJm3of0A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)