In humans, a minor subset of T cells express killer cell Ig-like receptors (KIRs) at their surface. In vitro data obtained with KIR+ β and γδ T-cell clones showed that engagement of KIR molecules can extinguish T-cell activation signals induced via the CD3/T-cell receptor (TCR) complex. We analyzed the T-cell compartment in mice transgenic for KIR2DL3 (Tg-KIR2DL3), an inhibitory receptor for HLA-Cw3. As expected, mixed lymphocyte reaction and anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (MoAb)-redirected cytotoxicity exerted by freshly isolated splenocytes can be inhibited by engagement of transgenic KIR2DL3 molecules. In contrast, antigen and anti-CD3 MoAb-induced cytotoxicity exerted by alloreactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes cannot be inhibited by KIR2DL3 engagement. In double transgenic mice, Tg-KIR2DL3 × Tg-HLA-Cw3, no alteration of thymic differentiation could be documented. Immunization of double transgenic mice with Hen egg white lysozime (HEL) or Pigeon Cytochrome-C (PCC) was indistinguishable from immunization of control mice, as judged by recall antigen-induced in vitro proliferation and TCR repertoire analysis. These results indicate that KIR effect on T cells varies upon cell activation stage and show unexpected complexity in the biological function of KIRs in vivo.

MOLECULES ENCODED by the class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are recognized by 3 distinct groups of cell surface immunoreceptors: the CD3/T-cell receptor (TCR) complex, CD8 dimers, and natural killer cell receptors (NKRs).1,2NKRs belong to 2 families of molecules: human killer cell Ig-like receptors (KIRs) and leukocyte Ig-like receptors (LIRs; also called Ig-like transcripts [ILTs]) are Ig-like receptors, whereas CD94-NKG2 heterodimers and mouse Ly-49 homodimers are C-type lectins.3-7 In contrast to the exquisite recognition of antigen-MHC complex by TCR polypeptides, the recognition of MHC class I molecules by KIRs, LIRs, and Ly-49 receptors is degenerated, because these NKRs interact with the products of multiple MHC class I alleles. Inhibitory and activating NKRs isoforms have been described.8,9 Inhibitory NKRs harbor intracytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs) that recruit and activate the protein tyrosine phosphatases SHP-1 and/or SHP-2.10,11 Activating NKRs lack ITIMs and associate with polypeptides containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), such as DAP-12/KARAP or FcRγ, which recruit and activate the protein tyrosine kinases ZAP-70 and/or p72 Syk.9,12-16Although the biological function of activating NKRs remains obscure, it is proposed that inhibitory NKRs confer to NK cells a molecular sensor device that allows the selective lysis of autologous cells with altered MHC class I expression.1,2 Such quantitative and/or qualitative defects in MHC class I surface expression are common alterations that occur upon tumor transformation and viral infection.17 18

A minor subset of T cells, in most instances CD8+ T cells, express KIRs.19 KIR+ T lymphocytes display a cell surface phenotype typical of memory T cells, and analysis of the TCR Vβ repertoire showed the oligoclonal or monoclonal nature of these populations, suggesting that KIRs are expressed de novo by T cells as a consequence of chronic antigen-driven activation in vivo.20-31 Consistent with these observations is the fact that KIR+ T cells are present in adult peripheral lymphoid tissue and blood, but absent in thymus or cord blood.21Analysis of KIR+ T-cell clones has shown that KIR engagement inhibits CD3/TCR-mediated T-cell activation in different experimental systems.19-31 In particular, it has been reported that KIR+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) fail to lyse antigen-presenting cells that express the KIR-cognate HLA class I molecules.26 30

We have generated transgenic mice for KIR2DL3 using an MHC class I promoter and an Ig enhancer.32 KIR2DL3 transgenic mice express the transgene on all NK cells, T cells, and a proportion of B cells. Because both CD4+ and CD8+ express KIR2DL3 at their surface, the KIR2DL3 transgenic mice represent a unique model to dissect the function of HLA class I-specific inhibitory receptors on T lymphocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

The KIR2DL3 transgenic mice (Tg-KIR2DL3) were described elsewhere.32 The transgenic founder mice ([B6×CBA]F2 mice) were backcrossed to both B6 and CBA backgrounds, and offspring were typed for H-2 alleles with monoclonal antibody (MoAb) specific for H-2Kb (20.8.4) and H-2Kk (11.4.1). The HLA-Cw3 transgenic mice of B6 background (Tg-HLA-Cw3) have been described.32 The Tg-HLA-Cw3 were backcrossed with CBA and offspring typed for H-2 alleles. All the mice were maintained at the Animal Facility of the Pasteur Institute (Paris, France). Nontransgenic wild-type mice (WT) were also used as controls.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

Spleen cells and thymocytes were stained as previously described and analyzed on a FACScan apparatus (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).32 Cells were stained with the following MoAbs: anti-HLA class I fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated; anti-KIR2DL3 phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated (Immunotech, Marseille, France); anti-CD3ε FITC- or PE-conjugated; anti-CD4 FITC- or PE-conjugated; anti-CD8 biotine-, FITC- or PE-conjugated (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); and tricolor (TC)-conjugated streptavidin (Caltag, San Francisco, CA).

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) and interleukin-2 (IL-2) production.

Unfractionated spleen cells (2 × 105) from WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 mice were stimulated with 4 × 105irradiated (3,000 rads) allogeneic spleen cells. No cytokines were added in the assay. After 3 days of culture, the cells were pulsed overnight with 1 μCi/well [3H]Thymidine (Amersham Life Science, Amersham, UK). The results of the assay were expressed as the mean of cpm of triplicate culture ± standard deviation. For the determination of IL-2 production, 100 μL of day-3 MLR supernatant was added to 104 CTLL-2, an IL-2–dependent cell line. After 24 hours of culture, the cells were pulsed overnight with 1 μCi/well [3H]Thymidine. Data represent the mean cpm from triplicate cultures ± standard deviation.

Generation of alloreactive CTLs and cytotoxicity assay.

Recipient mice were injected with 107 irradiated (3,000 rads) allogeneic splenocytes into the hind foot pads. After 3 days, the draining lymph nodes were collected and the cells were cultured for 4 more days in vitro in the absence of any stimulating cell in culture medium containing 40 U/mL recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2).33

Con-A–activated T-cell blasts were used as target cells in a standard 4-hour 51Cr release in vitro assay with primary in vivo-induced CTLs. Briefly, 107 spleen cells were cultivated for 48 hours in culture medium containing 2 μg/mL Con-A (Sigma Chemicals Co, St Louis, MO). Con-A blasts were labeled with 500 μCi 51Cr (Amersham) for 1 hour and added to the CTLs at various effector:target (E:T) ratios in 96-well U-bottom plates. After 4 hours at 37°C, 100 μL of supernatant was collected from each well and counted in a γ-counter for the determination of51Cr release and the percentage of specific lysis.

For the antibody-redirected killing assay, the murine mastocytoma cell line P815 was used as a source of target cells. Briefly, effector cells (alloreactive CTLs or freshly isolated splenocytes) were incubated with anti-CD3ε and anti-KIR2DL3 MoAbs, alone or in combination, before the addition of 51Cr-labeled P815 target cells at an E:T ratio of 5:1 for the CTLs and of 200:1 for the splenocytes. When freshly isolated splenocytes were used as effector cells, mice (WT and Tg-KIR2DL3) were injected with poly I:C 24 hours before the assay as described.32

Skin grafts.

Donor tail skin (1 cm2) was grafted onto the flank of recipient mice, which was then covered with pansement dressing. A plaster was applied and secured with an autoclip. Bandaging was removed 7 days later, and grafts were observed every day for rejection. Grafts were scored as being rejected when no viable tissue was visible.

Hen egg white lysozime (HEL) immunization.

HEL protein was purchased from Appligene (Illkrich, France). Mice were immunized in the hind foot pads with 3.5 nmol/L HEL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) emulsified 1:1 with complete Freund adjuvant (CFA). Nine days later, popliteal lymph nodes were collected.34 Lymph nodes cells were cultured (5 × 105/well) in fetal calf serum (FCS)-free medium HL-1 (Ventrex Laboratories, Portland, ME) supplemented with 2 mmol/L glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in the presence of different concentrations of HEL (from 0.1 to 50 μmol/L). The cells were incubated with 1 μCi/well [3H]Thymidine for the last 18 hours of a 4-day culture, and [3H]Thymidine incorporation was assayed by liquid scintillation counting. The results were expressed as the mean cpm of triplicate cultures ± standard deviation.

T-cell repertoire analysis.

Mice were immunized twice at 1-week intervals at the base of the tail either with 100 μg Pigeon Cytochrome-C (PCC) emulsified 1:1 in CFA or with CFA alone. After 1 week from the last immunization, the draining lymph nodes were collected and mRNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), as recommended by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized using (dT)17 primer and Moloney’s murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (GIBCO BRL) in the presence of RNasin (Promega, Madison, MI). Immunoscope analysis and Cβ-, Vβ-, and Jβ-specific primers have been previously described.35 Briefly, 1/10 of the cDNA was amplified in a 50 μL polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with Cβ and Vβ3.1 oligonucleotides. Each amplified product was then used as a template for elongation with Jβ-specific oligonucleotides with a fluorescent tag (run-off reaction), as described. The fluorescent run-off products were loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel and subjected to electrophoresis in an automated DNA sequencer. The CDR3 size distribution and signal intensities were then analyzed with the Immunoscope software.36

RESULTS

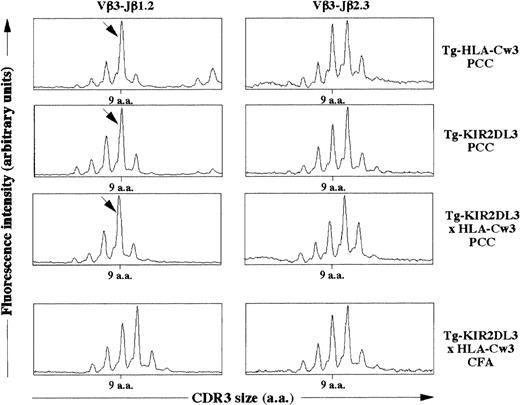

Inhibition of in vitro T-cell activation by engagement of KIR2DL3.

In Tg-KIR2DL3 mice, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express high levels of KIR2DL3 at their surface, and no KIR−CD3+ T cells could be detected (Table 1). We have previously shown that KIR2DL3 is able to confer specific inhibition of anti-CD3 MoAb-redirected cytotoxicity to T lymphocytes freshly isolated from these transgenic mice.32 To investigate whether other T-cell functions could be controlled by engagement of the KIR2DL3 molecule, we analyzed in vitro T-cell proliferation and IL-2 production in response to allogeneic stimulation. MLR were established using unfractionated spleen cells from WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 of H-2bhaplotype as responders. Allogeneic stimulator splenocytes from WT H-2k haplotype mice were able to induce proliferation of H-2b splenic T cells as well as H-2b splenic KIR2DL3+ T cells (Fig 1A). In contrast, when allogeneic H-2k cells expressing HLA-Cw3 were used as stimulators, a significant inhibition of T-cell proliferation was observed with responder T cells isolated from KIR2DL3 transgenic mice, but not with responder T cells isolated from WT mice (Fig 1A). The inhibition of T-cell proliferation correlates with a lower IL-2 production by Tg-KIR2DL3 responder T cells in the presence of HLA-Cw3+ stimulator cells (Fig 1B).

KIR2DL3 expression on T cells inhibits MLR. (A) The proliferation of splenic T cells from Tg-KIR2DL3 and WT mice of H-2b haplotype in response to allogeneic (H-2k) stimulator spleen cells was assessed by (3H)thymidine incorporation after 3 days of MLR. (B) IL-2 secretion in the supernatant of MLR at day 3 was assessed by measuring the proliferation of the IL-2–dependent CTLL-2 cell line. Data represent the mean values ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations of 1 out of 3 representative experiments. (▪) None; ( ) WT H2b; (▨) WT H2k; () Tg-HLA-Cw3 H2k.

) WT H2b; (▨) WT H2k; () Tg-HLA-Cw3 H2k.

KIR2DL3 expression on T cells inhibits MLR. (A) The proliferation of splenic T cells from Tg-KIR2DL3 and WT mice of H-2b haplotype in response to allogeneic (H-2k) stimulator spleen cells was assessed by (3H)thymidine incorporation after 3 days of MLR. (B) IL-2 secretion in the supernatant of MLR at day 3 was assessed by measuring the proliferation of the IL-2–dependent CTLL-2 cell line. Data represent the mean values ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations of 1 out of 3 representative experiments. (▪) None; ( ) WT H2b; (▨) WT H2k; () Tg-HLA-Cw3 H2k.

) WT H2b; (▨) WT H2k; () Tg-HLA-Cw3 H2k.

Regulation of in vivo T-cell activation by engagement of KIR2DL3.

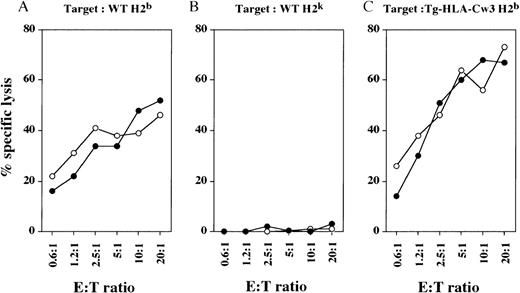

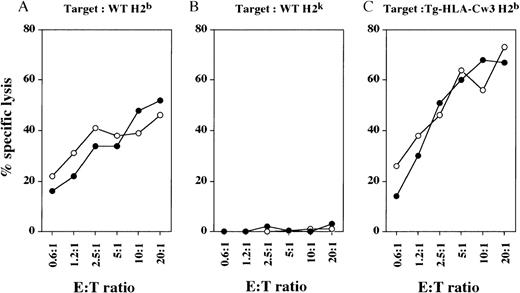

We generated mouse alloreactive CTLs by injecting irradiated spleen cells from allogeneic mice into the hind foot pads.33 In vivo-generated CTLs from WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 mice of H-2khaplotype were then tested for their cytolytic activity against syngeneic and allogeneic target cells. Both WT-derived and Tg-KIR2DL3–derived H-2k CTLs were able to efficiently lyse target cells from WT H-2b mice (Fig 2A), but not syngeneic target cells from WT H-2k mice (Fig 2B). Surprisingly, the expression of HLA-Cw3 on allogeneic H-2b target cells does not protect them from lysis by Tg-KIR2DL3–derived H-2k CTLs (Fig 2C).

Cytolytic activity of in vivo-generated CTL against allogeneic and syngeneic target cells. WT (○) and Tg-KIR2DL3 (•) mice of H-2k haplotype were injected into the hind foot pads with irradiated splenocytes from WT H-2b mice. Draining lymph node cells were tested against WT (A) and Tg-HLA-Cw3 (C) of H-2b haplotype and WT H-2k (B) ConA blasts. Data shown are representative from 3 independent experiments.

Cytolytic activity of in vivo-generated CTL against allogeneic and syngeneic target cells. WT (○) and Tg-KIR2DL3 (•) mice of H-2k haplotype were injected into the hind foot pads with irradiated splenocytes from WT H-2b mice. Draining lymph node cells were tested against WT (A) and Tg-HLA-Cw3 (C) of H-2b haplotype and WT H-2k (B) ConA blasts. Data shown are representative from 3 independent experiments.

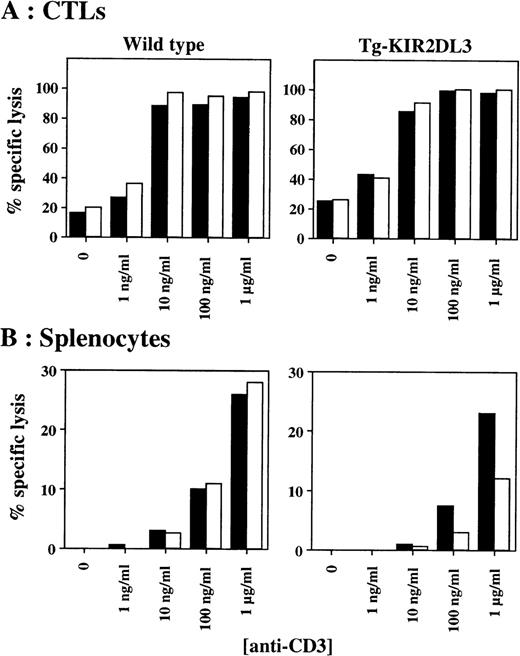

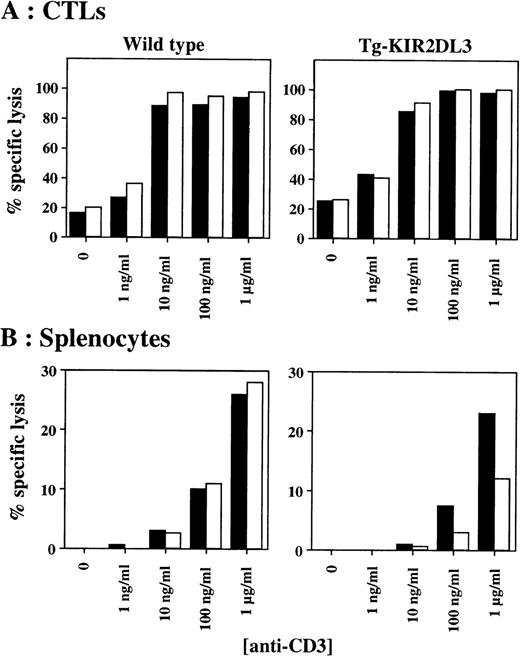

We further tested the in vitro cytotoxicity of in vivo-derived CTLs against P815 target cells in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-KIR2DL3 MoAbs. As shown in Fig 3A, anti-CD3 MoAb-mediated cytotoxicity of CTLs derived from Tg-KIR2DL3 mice is not inhibited in the presence of anti-KIR2DL3 MoAb. In contrast, splenic T cells freshly isolated from Tg-KIR2DL3 mice showed a decreased lytic activity against P815 target cells in the presence of anti-KIR2DL3 MoAb (Fig 3B), as we previously reported.32

Antibody-redirected cytolytic activity of freshly isolated splenocytes and in vivo–generated CTL. In vivo-generated CTL (A) and freshly isolated nonadherent splenocytes injected (B) from WT (left panels) and Tg-KIR2DL3 mice (right panels) were tested in a redirected killing assay against P815 target cells at an E:T ratio of 5:1 for the CTL and 200:1 for the splenocytes. (▪) Anti-CD3; (□) anti-CD3 + anti-KIR2DL3.

Antibody-redirected cytolytic activity of freshly isolated splenocytes and in vivo–generated CTL. In vivo-generated CTL (A) and freshly isolated nonadherent splenocytes injected (B) from WT (left panels) and Tg-KIR2DL3 mice (right panels) were tested in a redirected killing assay against P815 target cells at an E:T ratio of 5:1 for the CTL and 200:1 for the splenocytes. (▪) Anti-CD3; (□) anti-CD3 + anti-KIR2DL3.

To investigate the ability of KIR2DL3 to modulate T-cell functions in vivo, we studied allogeneic skin graft rejection. Tail skin grafts from Tg-HLA-Cw3 H-2k mice were grafted onto syngeneic Tg-HLA-Cw3 H-2k mice or allogeneic Tg-HLA-Cw3 or Tg-KIR2DL3 of H-2b haplotype. As shown in Table 2, the syngeneic grafts were accepted. In contrast, all H-2b allogeneic recipients (ie, Tg-HLA-Cw3 or Tg-KIR2DL3) rejected the skin grafts between 14 and 15 days. These results indicate that KIR2DL3 expressed on T cells from allogeneic recipient mice is unable to control T-cell–mediated skin graft rejection, despite cell surface expression of HLA-Cw3 on donor skins.

Analysis of KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 double transgenic mice.

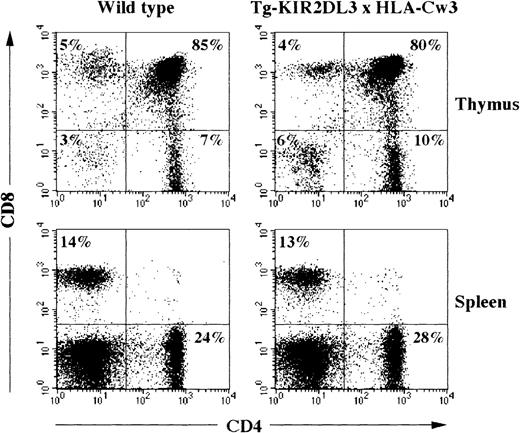

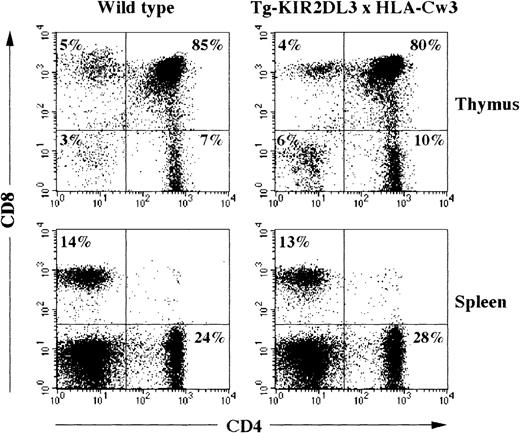

Double transgenic mice for KIR2DL3 and its ligand HLA-Cw3 were generated and analyzed for their T-cell compartment. All thymocytes and T lymphocytes express the KIR2DL3 receptor, and all bone marrow-derived as well as stroma-derived cells express the HLA-Cw3 molecule.32 37 Despite the early expression of both transgenic molecules during T-cell ontogeny, no alteration in the numbers and percentages of thymocytes and splenic T cells could be detected when comparing WT, simple transgenic littermates (Tg-HLA-Cw3 and Tg-KIR2DL3), and double transgenic animals (Table 3 and data not shown). Moreover, surface expression analysis of CD4 and CD8 molecules did not show any modification of T cells in double transgenic animals as compared with WT mice or single transgenic animals (Fig 4and data not shown).

Flow cytometric analysis of CD4 and CD8 expression on thymocytes and splenocytes of WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice. Freshly isolated thymocytes and splenocytes from WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 MoAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD4 and CD8 expression on thymocytes and splenocytes of WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice. Freshly isolated thymocytes and splenocytes from WT and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 MoAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry.

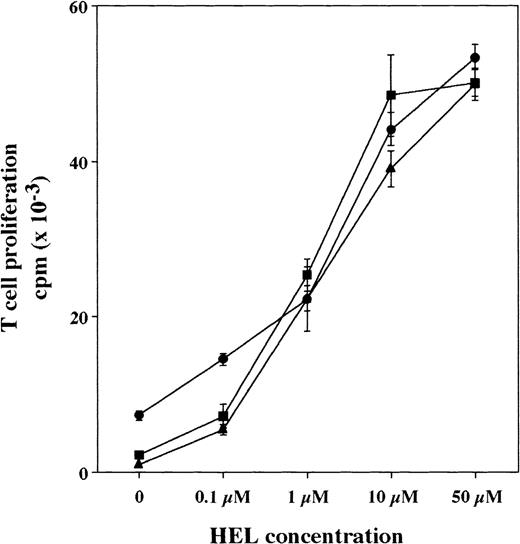

Tg-HLA-Cw3, Tg-KIR2DL3, and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice of H-2k haplotype were immunized with HEL. Nine days after HEL injection, the draining lymph nodes were collected and the lymph node cells were purified.34 The number of recovered lymph node cells after HEL immunization was similar in the 3 groups of mice (number of lymph node cells recovered × 106, mean ± SD, n = 6: 31 ± 7 for Tg-HLA-Cw3, 33.5 ± 5.4 for Tg-KIR2DL3, and 27.5 ± 7 for Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3). When lymph node cells were restimulated in vitro with various concentrations of HEL, the proliferative responses were similar in the 3 groups of mice (Fig 5). These results indicate that the double transgenic mice are able to respond to antigen immunization despite the presence of KIR2DL3 on T cells and HLA-Cw3 on antigen-presenting cells.

Proliferative response of HEL-primed Tg-HLA-Cw3, Tg-KIR2DL3, and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice lymph node cells. Tg-HLA-Cw3 (•), Tg-KIR2DL3 (▪), and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 (▴) mice were immunized with HEL, and the draining lymph node cells were isolated 9 days after the immunization. Lymph node cells were then restimulated in vitro in the presence of the indicated concentrations of HEL and cell proliferation was measured after 4 days of culture. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Proliferative response of HEL-primed Tg-HLA-Cw3, Tg-KIR2DL3, and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice lymph node cells. Tg-HLA-Cw3 (•), Tg-KIR2DL3 (▪), and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 (▴) mice were immunized with HEL, and the draining lymph node cells were isolated 9 days after the immunization. Lymph node cells were then restimulated in vitro in the presence of the indicated concentrations of HEL and cell proliferation was measured after 4 days of culture. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

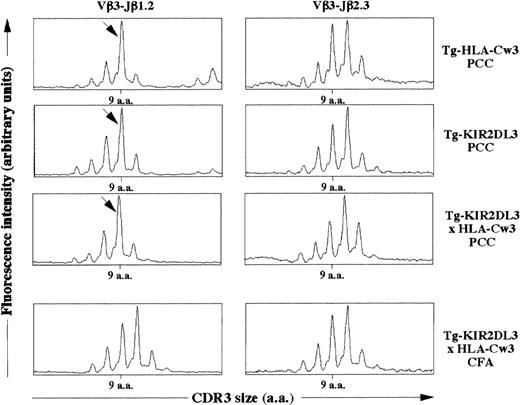

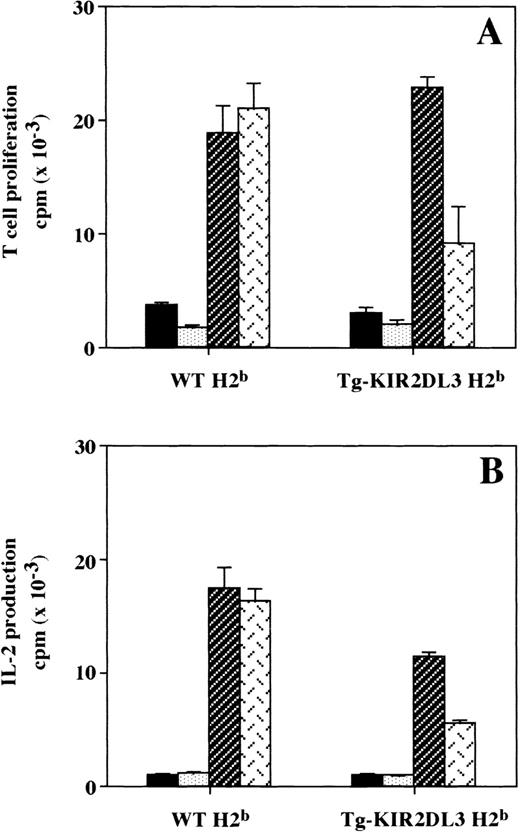

We then asked whether the simultaneous presence of KIR2DL3 and HLA-Cw3 within the thymus could induce changes in T-cell repertoire by modifying the threshold of positive and negative selection. It has been previously shown that the immune response against PCC in an H-2k background is characterized by the emergence of a dominant Vβ3-Jβ1.2 rearrangement with a 9 amino acid long CDR3β.35 To characterize the TCR repertoire of T lymphocytes specific for PCC, we immunized Tg-HLA-Cw3, Tg-KIR2DL3, and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 of H-2k haplotype with PCC. As shown in Fig 6, lymph node cells from all groups of mice immunized with PCC displayed an expansion corresponding to the described PCC-specific response. These results suggest that the TCRβ repertoire in Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice does not display major modifications.

CDR3β size distribution in PCC immunized mice. Tg-HLA-Cw3, Tg-KIR2DL3, and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice were immunized with PCC emulsified in CFA (PCC) as indicated. As a control, a group of Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice were injected with CFA alone. The mRNA was extracted from the draining lymph node cells and reversely transcribed into cDNA. The cDNA from the indicated mice was subjected to PCR using Vβ3.1- and Cβ-specific primers followed by a run-off with fluorescent Jβ1.2- and Jβ2.3-specific oligonucleotides. The size distribution was analyzed with the Immuoscope software. Data shown are representative from 3 mice per group. Analysis of Vβ3-Jβ2.3 was performed as a negative control. The arrows indicate the Vβ3-Jβ1.2 rearrangement with a 9 amino acid long CDR3β that is dominant upon PCC immunization.

CDR3β size distribution in PCC immunized mice. Tg-HLA-Cw3, Tg-KIR2DL3, and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice were immunized with PCC emulsified in CFA (PCC) as indicated. As a control, a group of Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice were injected with CFA alone. The mRNA was extracted from the draining lymph node cells and reversely transcribed into cDNA. The cDNA from the indicated mice was subjected to PCR using Vβ3.1- and Cβ-specific primers followed by a run-off with fluorescent Jβ1.2- and Jβ2.3-specific oligonucleotides. The size distribution was analyzed with the Immuoscope software. Data shown are representative from 3 mice per group. Analysis of Vβ3-Jβ2.3 was performed as a negative control. The arrows indicate the Vβ3-Jβ1.2 rearrangement with a 9 amino acid long CDR3β that is dominant upon PCC immunization.

DISCUSSION

Inhibitory KIRs have been initially characterized on NK cells as MHC-specific receptors whose engagement leads to inhibition of NK cytolytic activity.38 Consistent with these seminal observations, the transgenic expression of KIR2DL3 confers a negative control to NK cells upon interaction with cognate HLA-Cw3 molecules expressed on target cells.32 On NK cells, KIRs are thus thought to act as sensor molecules to detect the quality as well as the quantity of self MHC class I molecules expressed on autologous cells and to restrict the NK effector function towards cells expressing no or altered self MHC class I molecules. Discrete subsets of T cells also express KIRs, but the biological significance of KIR expression on T lymphocytes remains elusive. KIR+ T cells have been shown to present a cell surface phenotype typical of memory T cells as indicated by expression of CD45R0 and CD29 as well as by the lack of CD28 and CD45RA.24 KIRs can act as inhibitory molecules on T-cell clones, as shown in several experimental in vitro models, such as CD3/TCR-mediated cytolysis.19-22,27-30 It has also been shown that treatment of KIR+ T-cell clones with anti-KIR and anti-HLA class I MoAb leads to an increased tumor necrosis α (TNFα) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by CD4+and CD8+ T-cell clones.23 These results suggested that recognition of autologous MHC class I molecules by KIR+ T cells might provide a mechanism for limiting T-cell activation, which could be involved in the maintenance of tolerance or prevention of autoimmunity.23 Melanoma-specific KIR+ CTL cell clones have also been described.26 Such KIR+ CTLs are active only against tumor cells showing a partial MHC class I loss, eg, the cognate MHC class I molecule that interacts with the given KIR.26In these circumstances, expression of KIRs on T cells appears to be deleterious for antitumor immunity.

We have analyzed the T-cell compartment in Tg-KIR2DL3 and Tg-KIR2DL3 × HLA-Cw3 mice, which represent a unique model to dissect the consequence of a single KIR expression on T cells in the presence or absence of the cognate HLA-Cw3 ligand. Unexpectedly, the transgenic expression of KIR2DL3 on mouse T cells reveals that the inhibition of T-cell activation induced by KIR cannot be detected in vitro using in vivo-primed T cells (Figs 2 and 3A). Furthermore, no attenuation of in vivo T-cell response can be detected in KIR2DL3 transgenic mice (Table2) or in double transgenic mice coexpressing KIR2DL3 and its ligand HLA-Cw3 (Figs 5 and 6).

We previously demonstrated that the transgenic KIR2DL3 molecule is capable of coupling to mouse NK cell inhibitory pathways, because NK cells isolated from KIR2DL3 transgenic mice are tolerant in vitro and in vivo to HLA-Cw3+ target cells.32 Similarly, engagement of KIR2DL3 can inhibit anti-CD3 MoAb-redirected cytotoxicity exerted by mouse splenocytes freshly isolated from KIR2DL3 transgenic mice (Cambiaggi et al32 and Fig 3B), as well as MLR towards HLA-Cw3+ targets (Fig 1). Therefore, we can rule out the possibility that the heterologous expression of human KIRs in mouse lymphocytes and the level of expression of KIR2DL3 and HLA-Cw3 in transgenic mice are responsible for the lack of inhibitory function exerted by the transgenic KIR2DL3 molecules on mouse T cells.

T-cell activation is controlled by a dynamic balance between activating and inhibitory signals.39 A feature of all ITIM-bearing molecules, including KIRs, is that their engagement sets a threshold of cell activation, which can be bypassed using increasing amounts of activating reagents, such as antigen or agonist MoAbs.10,32 40 It is therefore possible that the absence of inhibition mediated by the transgenic KIR2DL3 molecule on mouse T cells is merely the consequence of a quantitative insufficiency of KIR inhibitory mechanisms to antagonize full-blown T-cell activation. In this regard, the potent in vitro CTL activation induced by alloantigen is refractory to KIR inhibition (Fig 2), and KIR2DL3 transgenic mice are not tolerant to HLA-Cw3+ allogeneic skins (Table 2). Consistent with these data, anti-CD3 MoAb-redirected lysis exerted by primed CTLs is not inhibited by KIR engagement (Fig 3A), in contrast to anti-CD3 MoAb-redirected lysis of freshly isolated splenocytes (Fig3B). This discrepancy may be the direct consequence of the higher efficiency of primed CTLs to exert cytotoxicity as compared to freshly isolated splenocytes.

Alternatively, it is also possible that the lack of KIR inhibitory function on T cells is the consequence of the coupling of KIRs to downstream effector molecules distinct from SHP-1 and SHP-2 protein tyrosine phosphatases. In particular, it has been shown that the p85α regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase can be recruited by KIR phospho-ITIMs.41 It is therefore possible that, depending on the activation status of lymphocytes, KIRs may either couple to SHP-1/SHP-2 or to PI 3-kinase. Such a differential recruitment may occur through a variable KIR accessibility to these downstream effector molecules. Similarly, engagement of FcγRIIB, another ITIM-bearing molecule has been shown either to extinguish B-cell activation through the recruitment of SHIP or to result in enhanced apoptosis through a still-undefined mechanism.42Such developmental regulation of KIR accessibility to protein tyrosine phosphatases or other downstream effector molecules remains to be further dissected.

It has been suggested that KIR expression on T cells allows the cells to downmodulate or terminate an immune response and might therefore be involved in the control of peripheral tolerance. This hypothesis needs to be re-evaluated, because our results show that the signals induced upon KIR engagement are not sufficient to modulate in vivo T-cell response to antigen. Moreover, once T cells have been activated in vivo, they become refractory to KIR-mediated inhibition. Similarly, KIR2DL3 engagement is unable to control T-cell cytotoxicity on a fraction of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific KIR+ T-cell clones derived from EBV-infected patients (Couedel et al, unpublished results). Therefore, strategies aimed at controlling T-cell activation through the manipulation of KIR expression on T cells should be reconsidered. In contrast to KIRs, the cell surface expression of lectin-like NKRs, such as CD94-NKG2 dimers, is heavily controlled by cytokines.31,43,44 It will be of interest to investigate whether the in vivo function of lectin-like NKRs, such as CD94-NKG2 dimers, correlates with their in vitro inhibitory function on CD3/TCR-induced T-cell activation.45 46

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Drs Margarita Salcedo, Philippe Bousso (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), Marc Bonneville (INSERM U463, Nantes, France), and Sophie Ugolini (CIML, Marseille, France) for helpful discussions and thank Corinne Béziers La Fosse (CIML) for graphics.

Supported by institutional grants from INSERM, CNRS, and Ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche and by specific grants from Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (E.V. and P.K.), Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (E.V. and P.K. subvention: axe immunologie des tumeurs), and the Training and Mobility of Researcher Programme (A.C.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Eric Vivier, DVM, PhD, Centre d’Immunologie INSERM/CNRS de Marseille-Luminy, Case 906, 13288 Marseille cedex 09, France; e-mail: vivier@ciml.univ-mrs.fr.

) WT H2b; (▨) WT H2k; () Tg-HLA-Cw3 H2k.

) WT H2b; (▨) WT H2k; () Tg-HLA-Cw3 H2k.