The Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) has restricted temporal and spatial expression patterns during development, and several members are also found to be upregulated in tumors. Very little is known of the promoter elements or regulatory factors required for expression of Eph RTK genes. In this report we describe the identification and characterization of the EphA3 gene promoter region. A region of 86 bp located at −348 bp to −262 bp upstream from the transcription start site was identified as the basal promoter. This region was shown to be active in both EphA3-expressing and -nonexpressing cell lines, contrasting with the widely different levels of EphA3 expression. We noted a region rich in CpG dinucleotides downstream of the basal promoter. Using Southern blot analyses with methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes and bisulfite sequencing of genomic DNA, sites of DNA methylation were identified in hematopoietic cell lines which correlated with their levels of EphA3 gene expression. We showed that EphA3 was not methylated in normal tissues but that a subset of clinical samples from leukemia patients showed extensive methylation, similar to that observed in cell lines. These results suggest that DNA methylation may be an important mechanism regulating EphA3 transcription in hematopoietic tumors.

THE EPH RECEPTOR FAMILY is the largest subfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases.1 The receptors can be divided into 2 groups, EphA and EphB, based both on sequence similarities of their extracellular domains and their ability to bind to either the glycosyl-phosphatidyl-inositol (GPI)-linked ligands (ephrin-A ligands) or the transmembrane ligands (ephrin-B ligands), respectively.1 These molecules display dynamic temporal and spatial expression patterns during embryogenesis, and several studies have suggested that they may play a role in early tissue patterning events.2-4 Many Eph receptors and ligands are expressed in the developing nervous system, and both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that these molecules function in axon guidance and fasciculation.5-9 Some receptors and ligands are also highly expressed outside the nervous system, for example in endothelium, where they appear to be involved in cell growth and migration.10-12

The human EphA3 (Hek) receptor was first isolated from a pre-B leukemic cell line (LK63). In normal human tissues, EphA3 mRNA is not detectable by Northern blot analysis13,14 but can be detected by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in thymus lymphocytes, bone marrow, and brain (J. Olsson, A. Boyd, unpublished results, November 1994). The receptor is found in lymphoid tumor cell lines including the human T-cell lines Jurkatt, JM, HSB-2, and Molt-4.13,14 From the tumor cell lines examined, the gene structure and sequence of the receptor is normal and there is no gene amplification or rearrangement, nor is the gene associated with any chromosomal translocation.14 15 This implies that the high-level expression in some neoplasms may be due to alterations in transcriptional control.

The mouse (Mek4) and chicken (Cek4) EphA3 homologues were shown to be expressed in both temporally and spatially restricted patterns during embryogenesis. However, in keeping with results found in human tissues, the expression of EphA3 in the adult animal appears to be restricted to the central nervous system.16,17 The mechanism of control of this restricted pattern of expression is an important issue given the role of these molecules as cell guidance signals during development.5-12 This question and the high-level expression of EphA3 in a subset of hematopoietic tumors13-15 led us to investigate the mechanism(s) of regulation of the EphA3 gene. In this report, we describe the EphA3 gene proximal promoter and identify one mechanism that may regulate EphA3 transcription. The full characterization of a 1.4-kb genomic fragment containing exon 1 and 5′ upstream sequence of EphA3 gene is described. This fragment encodes the EphA3 core promoter region and contains an area rich in CpG dinucleotides downstream of the promoter. Southern analyses and bisulfite genomic sequencing show a correlation between the state of DNA methylation within the CpG-rich region and the levels of EphA3 gene expression in various hematopoietic cell lines and in clinical tumor samples. These findings suggest that DNA methylation is a major regulator of EphA3 transcription in hematopoietic tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Cell lines were maintained in either Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DME) or Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI-1640) supplemented with 0.01 mol/L NaCl, 0.02 mol/L NaHCO3, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 0.1 g/L streptomycin, 0.06 g/L penicillin, 5% to 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (CSL Laboratories, Parkville Victoria, Australia) in a 10% CO2-air incubator at 37°C. The LK63 and Lila-1 cell lines were derived as described.18 A subclone of the tetraploid-variant LK63 cell line that had been selected for expression of higher EphA3 receptor numbers was used for the EphA3 expression studies. Other lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA).

Peripheral blood samples.

Blood was taken from patients at diagnosis or relapse after appropriate informed consent. The heparinized blood obtained was separated on Ficoll Hypaque (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech AG, Sweden) gradients and the mononuclear fraction was isolated and prepared for flow cytometric analysis and DNA preparation.

Flow cytometric analysis (FCA).

Cell-surface expression of EphA3 was assessed by indirect immunofluorescence with the III.A4 (IgG1, κ) antibody as previously described.13 Samples were analyzed on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) or a Coulter Profile (Coulter, Hialeah, FL).

Determination of EphA3 receptor number on cell lines.

A nonradioactive method to determine receptor numbers on LK63 cells was developed using microbeads (Quantum Simply Cellular; Sigma, Sydney, Australia). These beads have a defined number of antigenic sites (goat anti-mouse Ig antibody) for mouse monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs). This allowed calculation of the fluorescence/protein ratio of the III.A4 antibody and, thus, estimation of receptor number from flow cytometric estimation of total fluorescence of labeled cells. Flow cytometry of cells labeled with the anti-EphA3 MoAb IIIA.4 was used to quantitate the number of EphA3 receptors on the surface of cell lines (as per manufacturer’s directions). For Scatchard analysis, purified III.A4 antibody was radioiodinated19 and the analysis was performed as previously described.14

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from 2 million cells using RNAzol (Advanced Biotechnologies Ltd, Surrey, UK) and then diluted to a concentration of 50 ng/mL, and 1-μL aliquots were used as a template in a 50-μL PCR reaction. Amplification of EphA3 and GAPDH cDNA were performed using the Perkin and Elmer Taqman kit (Melbourne, Australia). Contaminating DNA was removed by substituting dUTP for dTTP and treating the reaction mix with uracil N-glycosylase before PCR amplification. The EphA3 primer sequences were 5′ GCACAACAGGTGACTGGCTTAAT 3′ and 5′ CATCTGTGGAAATCTTGGCTATTG 3′. The EphA3 fluorigenic probe sequence was 5′ CCGGACAGCACACTGCAAGGAAATCT 3′. The GAPDH primers and probe were provided by the manufacturer. The cycling reaction was performed on an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer, Melbourne, Australia). Cycling parameters were 50°C for 2 minutes, 60°C for 30 minutes, and 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 94°C for 20 seconds and 62°C for 1 minute. Three replicates of each sample were analyzed.

Isolation of the 5′-region of the EphA3 gene.

A 12.4-kb genomic clone containing exon 1 of EphA3 gene was isolated from screening a human λ FIX II genomic library (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The EphA3 probe used for screening corresponded to the 5′ untranslated and signal sequence which together spanned the first 186 bp of EphA3 cDNA.14 From this clone, a 1.4-kb SacI fragment was subcloned intoSacI sites of pGEM-7 (Promega, Sydney, Australia) and sequenced using the standard techniques (Applied Biosystems Inc, Foster City, CA). The genomic fragment contained exon 1 of the EphA3 gene including 5′-flanking sequence.

Isolation of poly A+RNA and amplification of hEphA3 mRNA 5′ terminus from EphA3 cDNA.

Total RNA was isolated from LK63 cells using the protocol as described.20 To extract poly A+RNA, a pellet of total RNA (0.5 to 1 mg) was resuspended in 1 mL TES buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]). A column of 50 mg oligo dT cellulose type 3 (5′3′ Inc, Boulder, CO) was made in 1 mL 0.1 mol/L NaOH, per milligram of total RNA. The column was neutralized with several volumes of diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated H2O. The RNA was heated to 70°C for 3 minutes and then immediately placed at 4°C. Lithium chloride was added to the RNA to a final concentration of 0.5 mol/L and then added to the column bed. The column was vortexed, allowed to settle, and 3 mL of loading buffer (0.5 mol/L lithium chloride, 10 mmol/L Tris pH 7.5, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1% SDS) was added. After the elution of the loading buffer, 3 mL of wash buffer (0.15 mol/L lithium chloride, 10 mmol/L Tris pH 7.5, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1% SDS) was added. The poly A+ RNA was eluted from the column with 3 mL elution buffer (2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.1% SDS) and then precipitated and resuspended in DEPC-treated H2O.

The 5′-AmpliFINDER RACE kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was used to determine the transcription start site of the EphA3 gene. EphA3 cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg poly A+ RNA isolated from LK63 cells using an antisense EphA3-specific primer (P1 or P2). An AmpliFINDER anchor primer and an EphA3-specific nested primer (P2, P3, P4, or P5) were used to amplify from the anchor-ligated EphA3 cDNA. The primer sequences are: P1 CCCATGTGATGGATAAGAGATCC, P2 CATTGGAAGGCTGCGGAATC, P3 CATGCCACTGATGTGAG, P4 AGAGCGGGATGGCACGCAG, and P5 CCAGAGCTGCTCGGG. The PCR reaction was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 0.8% TBE agarose gel. PCR products were excised and purified with glass milk following the GENECLEAN II procedure (BIO 101, Vistar, CA). The purified single DNA band was then either directly sequenced using EphA3-specific primers or subcloned into pGEM-T (Promega) and sequenced using vector primers.

Deletion constructs of 5′ upstream EphA3.

The EphA3 genomic fragment was used as a template to synthesize various truncated PCR products and develop a series of deletion reporter gene constructs. The primers used for amplification were a 3′-antisense primer (TAGGCTAGCAAGGAGACCGGGTGGGA) that bound at the transcription start site in conjunction with different 5′-sense primers that bound at varying distances within the EphA3 gene upstream flanking sequence (see Fig 3). A restriction site forSacI was contained within each upstream primer and the downstream primer contained a BglII site to facilitate subcloning of the amplified product. The PCR fragments were digested with SacI and BglII and inserted into the multiple cloning region of the basic pGl2 luciferase expression construct (Promega) previously digested with the same enzymes. These deletion constructs were sequenced for verification of no PCR errors. The nomenclature used for each deletion construct shown in Fig 3indicates the number of bases of upstream 5′-flanking sequence relative to the transcription start site.

Transient transfection and luciferase assays.

The 293T cells were transiently transfected using a lipid carrier, LipofectAMINE (GIBCO-BRL, Melbourne, Australia), and Raji cells were transfected by electroporation. The assay times for the 293T cells and Raji cells were 48 and 24 hours, respectively. These times were determined to ensure that the cells recovered from the transfection procedure and that protein synthesis would occur.

Forty-eight hours before LipofectAMINE transfection, cells were plated in 6-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well grown in the above standard conditions. The cells were then rinsed twice with serum-free culture media, the media was removed, and DNA/LipofectAMINE mix was added (1 mL/well). The DNA/LipofectAMINE mix was made in serum-free media and incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature before adding to the cells. The mix consisted of 1 μg luciferase construct plasmid, 0.1 μg pSV-β-galactosidase plasmid (Promega), and 4 μL LipofectAMINE per well. Cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37°C and 10% CO2, and then FCS (10% per well) and FCS-containing media were added to each well and incubated for 48 hours in the standard conditions. For electroporation, logarithmically growing Raji cells were harvested, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in culture medium without FCS at a density of 1 × 107 cells per transfection. A BioRad GenePulser (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and 0.4-cm electrode gap cuvettes were used for electroporation. Cells and DNA (10 μg luciferase construct plasmid and 5 μg pSV-β-Galactosidase plasmid) were mixed in a 0.5-mL suspension within the cuvette and pulsed at 280 V/960 μFD. The cells were then incubated in 5 mL culture media for 24 hours.

Luciferase activity was measured using the luciferase assay system (Promega). Briefly, cells were lysed in 100 μL cell lysis buffer (Promega) and 20 μL used for luminometry in a Lumat LB 9501 (Berthold Australia, Bundoora Victoria, Australia) and 20 μL used for assaying β-galactosidase activity to monitor transfection efficiencies. Activity of β-galactosidase was measured using an assay that measures the cleavage of 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-D-galactoside (MUG) (Sigma) by β-galactosidase to yield the fluorescent molecule 4-methyumbelliferone (MU). Briefly, 10% volume of cell lysate (20 μL) was added to 430 μL of Z buffer (60 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 40 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 10 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/LMgSO4). A stock solution of 30 mmol/L MUG in dimethylformamide was freshly diluted 1:10 with Z buffer and 120 μL of this 3 mmol/L solution was added to diluted cell extract. The cell solution was protected from light and incubated at 37°C for 1 to 6 hours. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 400 μL stop buffer (300 mmol/L glycine, 15 mmol/L EDTA). Fluorescence of cell samples and MU standards were measured using a TKO 100 Mini-Fluorometer (Hoeffer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA). Three transfections of each construct plasmid were used in every assay.

Preparation of genomic DNA and genomic Southern blot analyses.

Genomic DNA was isolated from mononuclear cells isolated as described above. The mononuclear cells were washed and the cell pellet resuspended in 1 mL lysis buffer (100 mmol/L Tris.HCl pH 8.5, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 0.2% SDS, 200 mmol/L NaCl, 100 μg proteinase K/mL) and rotated for 2 hours or overnight at 55°C. Equal volume of isopropanol was added to the solution and gently mixed to precipitate the DNA. The precipitated DNA was washed twice with 70% ethanol and dissolved in 100 μL to 500 μL TE.

Genomic DNA (5 to 10 μg) was digested for 4 hours or overnight in a 40-μL restriction enzyme mix. The digests were electrophoresed through 0.8% TBE agarose gels containing 500 ng/mL ethidium bromide and vacuum blotted onto Zetaprobe membrane (BIO-RAD) with 0.25 mol/L HCl for 20 minutes and then 0.4 mol/L NaOH for 4 hours at 50 millibar. After transfer, membranes were rinsed in 2X SSC and dried at 80°C. The membrane filters were prehybridized at 42°C in 50% formamide, 10X Denhardt’s solution,21 0.05 mol/L Tris-Cl pH 7.5, 1.0 mol/L NaCl, 2.24 mmol/L tetra-sodium pyrophosphate, 1% SDS, 10% dextran sulfate, and 0.1 mg/mL sheared, heat-denatured herring sperm DNA. The cDNA probe was radioactively labeled by random priming (Stratagene) and purified from unincorporated nucleotide on a Nuctrap column (Stratagene). The heat-denatured probe was added to the prehybridization solution (1 × 106 cpm/mL) and the membranes hybridized at 42°C for 16 hours. Washes were performed at 68°C in 0.1X SSC, 0.1% SDS for 1 hour and in 0.1X SSC, 0.5% SDS for a further 30 minutes. Filters were exposed to autoradiography film overnight at −70°C, or placed in a phosphoimager cassette for 4 hours.

Bisulfite modification of genomic DNA.

Genomic DNA was extracted from human blood and tumor cell lines using the protocol outlined above. DNA (1 μg) was then bisulfite-treated using the procedure as described.22 23 Modified DNA was subsequently purified using a GENECLEAN kit (BIO 101) as recommended by the manufacturer, then desulfonated by incubating in a final concentration of 0.3 mol/L NaOH at 37°C for 20 minutes. Modified, desulfonated DNA was then precipitated and resuspended in a volume of 20 μL dH2O for PCR analyses. The two primers used for the first PCR reaction were 5′ GTTAGATTTAGTAAAAAGTTATGATATT 3′ and 5′ CCTAACTTACCTTCATTAAAAAACTAC 3′. The PCR reaction was in a total volume of 50 μL and consisted of 20 μL bisulfite-modified DNA, 100 ng of each primer, 2.0 mmol/L MgCl, 100 μmol/L dNTPs, and 1 U Taq polymerase with the appropriate reaction buffer supplied by the manufacturer. The cycling reaction was 10 cycles of 96°C for 30 seconds, 68°C for 30 seconds (−1°C per cycle), and 72°C for 1 minute, followed by 30 cycles of 96°C for 30 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute. A second nested PCR reaction was performed using 20 μL of the first PCR reaction and the same reaction mix as above except using the primers 5′ GTTAGATTTAGTAAAAAGTTATGATATT 3′ and 5′ ACTAACAATCCATATTACTAATAC 3′. The nested cycling reaction was 12 cycles of 96°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds (−0.5°C per cycle), and 72°C for 1 minute, followed by 30 cycles of 96°C for 30 seconds, 54°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute. PCR products were purified using a GENECLEAN kit and sequenced directly using PCR primers with dye terminator cycle sequencing reagents (Applied Biosystems Inc).

RESULTS

Detection of EphA3 expression in cell lines.

Table 1 summarizes analysis of EphA3 expression in human hematopoietic cell lines derived from FCA, from quantitative PCR, and from estimates of receptor number determined by the Quantum Microbead Assay (QMA). To validate the latter technique, we first needed to show that the anti-human EphA3 (IIIA4) MoAb bound only 1 site on the EphA3 molecule. Scatchard analysis with IIIA4 had been used previously to show that the original LK63 cell line expressed 15,000 receptors per cell.14 In these studies, an LK63 cell subline selected for high expression by flow cytometry (LK63hi) was used (A.W.B., unpublished data, January 1996). We compared the microbead method with Scatchard analysis to determine the receptor number per cell on the high expression LK63hi cell line and on Raji cells. On the LK63hi cells, Scatchard analysis detected 74,000 receptors per cell (data not shown), which compared well with the QMA estimation of 78,000 binding sites per cell. Raji cells were negative for EphA3 expression by both techniques.

Several T-cell lines were also shown to express EphA3 at high levels. Molt-4 displayed 16,900 and JM displayed 6,800 receptors per cell, in reasonable agreement with the 9,500 receptors/cell for the JM cell line determined previously by Scatchard analysis.14 HSB-2, which expressed EphA3 weakly, had been shown to express approximately 1,000 receptors by Scatchard analysis.14 No EphA3 expression was detected in the T-cell line HPB-ALL; in the myeloid lines HL60, U937, and RC2a; or in the pre-B cell line Lila-1. These results correlated well with previous qualitative estimates derived from inspection of flow cytometry results and Northern analyses.13 14 In addition, results obtained from quantitative real-time PCR showed a very good correlation of mRNA content with receptor number for JM, HSB2, LK63, and Raji cell lines (Table 1).

Isolation of the 5′-region of the EphA3 gene.

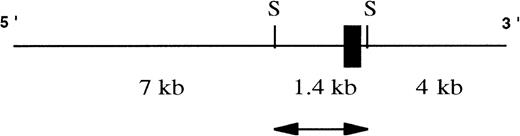

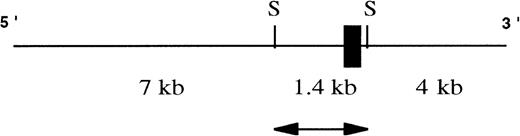

To investigate the great variation in EphA3 expression in different hematopoietic tumor lines, the 5′ upstream regulatory region of the EphA3 gene was isolated and characterized. A 12.4-kb genomic clone containing exon 1 of EphA3 gene was isolated from screening a human λ FIX II genomic library with an N-terminal probe derived from the EphA3 cDNA sequence (Fig 1). Restriction map analyses of the clone found exon 1 to be contained within a 1.4-kbSacI fragment. The 1.4-kb SacI fragment was then subcloned into SacI sites of pGEM-7 and fully sequenced. Sequence analysis showed the genomic fragment to contain exon 1 of the EphA3 gene with 5′-flanking sequence and 30 bp of intron 1. Exon 1 consists of 5′ noncoding sequence and the first 98 bp of the coding region.

A schematic representation of the human genomic clone isolated from λ FIX II genomic library. Exon I (black box) of the hEphA3 gene is within a 1.4-kb SacI fragment (arrow) that was subcloned and fully sequenced for further analyses. SacI sites are denoted as S.

A schematic representation of the human genomic clone isolated from λ FIX II genomic library. Exon I (black box) of the hEphA3 gene is within a 1.4-kb SacI fragment (arrow) that was subcloned and fully sequenced for further analyses. SacI sites are denoted as S.

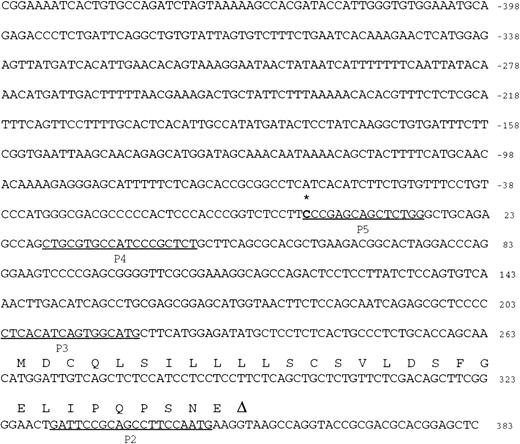

Identification of EphA3 transcription initiation site.

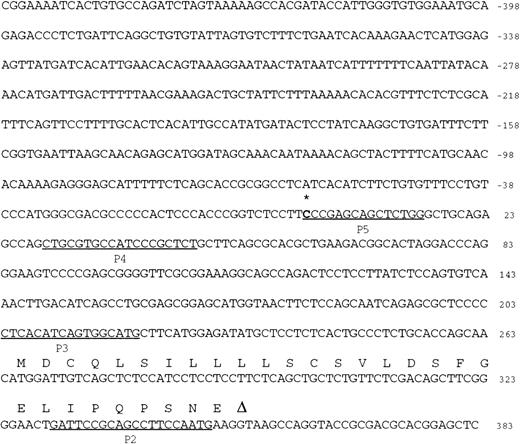

A 5′ RACE PCR technique was used to locate the transcription initiation site (TIS) of EphA3. Nested EphA3 specific antisense primers close to the 5′ end of the mRNA were synthesized (see Materials and Methods). The most 3′ primer (P1) was used in first-strand cDNA synthesis from preparations of poly A+ mRNA from an EphA3-expressing pre-B tumor cell line, LK63. After ligation with an anchor sequence, the cDNA was amplified with the nested 3′ primers and a sense primer directed to the anchor sequence (Fig 2). These products were subcloned and sequenced using vector primers. Sequence analysis was used to show that these products had the same 5′ terminal sequence, starting at −264 bp upstream from the first coding methionine (Fig 2). No further 5′ upstream sequence was amplified using other combinations of first-strand/nested primers, P1/P4, P1/P5, and P2/P4. These results indicate that the TIS of EphA3 gene begins at −264 bp upstream from the translation start site identified in the published EphA3 cDNA sequence.14

Nucleotide sequence of exon 1 and 5′ flanking sequence of the human EphA3 gene. Numbering of nucleotides is relative to the transcription initiation site (bolded and below the asterisk) as determined by RACE PCR. For the coding part of exon 1, the amino acid sequence is given above the nucleotide sequence in the one-letter code. The consensus GT of the splice donor is noted (below triangle). The positions of primers (P2-P5) used to identify the transcription initiation site are underlined.

Nucleotide sequence of exon 1 and 5′ flanking sequence of the human EphA3 gene. Numbering of nucleotides is relative to the transcription initiation site (bolded and below the asterisk) as determined by RACE PCR. For the coding part of exon 1, the amino acid sequence is given above the nucleotide sequence in the one-letter code. The consensus GT of the splice donor is noted (below triangle). The positions of primers (P2-P5) used to identify the transcription initiation site are underlined.

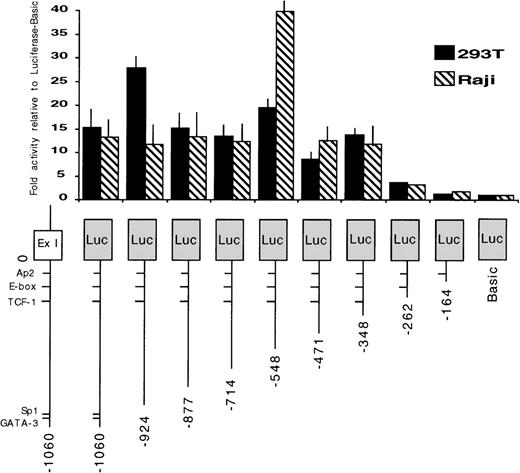

Identification of the minimum 5′ regulatory region required for EphA3 gene transcription.

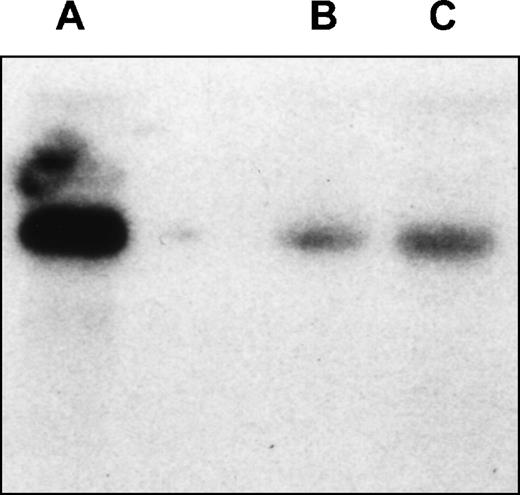

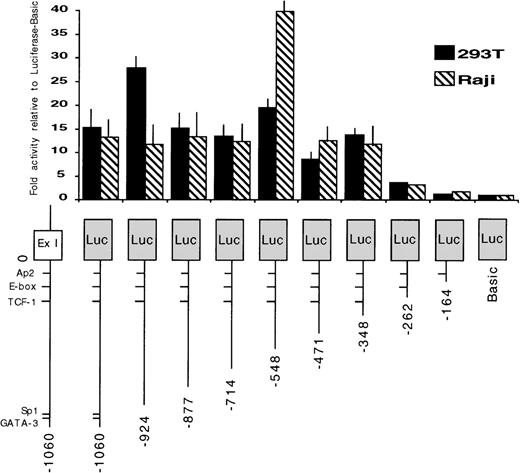

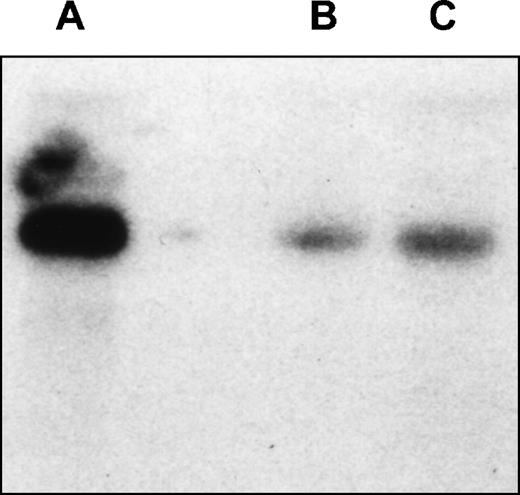

To identify the regions required for transcription activity of the EphA3 gene, a series of chimeric constructs containing different lengths of the 5′ flanking region of the EphA3 gene were fused to the luciferase pGL2 reporter gene (Fig 3). The 3′ ends of all inserts extended to the TIS and the longest construct extended to the 5′ end of the 1.4-kb fragment. The deletion mutants were transiently expressed by cotransfection of individual constructs with the pSV-βGal vector. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activities, and the mean value results of independent experiments are shown in Fig 3. Two human cell lines, the 293T cells and Raji cells, were used in these experiments. Raji is a B-cell line that does not express EphA3 (Table 1), whereas, by Northern analysis, 293T cells show a moderate level of EphA3 expression (Fig 4). No results were obtained from the LK63 line as, despite trying several methods of transfection, no transfection was achieved. As the levels of EphA3 expression in 293T cells were comparable to other EphA3 expressing hematopoietic lines, such as the HEL and JM cell lines (Table 1), the 293T cell line was considered to be a suitable positive control in these experiments.

Promoter activity of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene and various deletion mutants. On the bottom is a schematic representation of the EphA3 gene 5′ region. The various genomic fragments were cloned as PCR products 5′ to the luciferase reporter. The numbering is relative to the transcription initiation site (0). Luciferase activities of each transfected construct were normalized to β-galactosidase activities. Each transfection was assayed at least 3 times and the mean values are shown on the graph (error bars indicate sample standard deviation).

Promoter activity of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene and various deletion mutants. On the bottom is a schematic representation of the EphA3 gene 5′ region. The various genomic fragments were cloned as PCR products 5′ to the luciferase reporter. The numbering is relative to the transcription initiation site (0). Luciferase activities of each transfected construct were normalized to β-galactosidase activities. Each transfection was assayed at least 3 times and the mean values are shown on the graph (error bars indicate sample standard deviation).

Northern analysis of EphA3 expression in LK63hi and 293T cell lines. Hybridization of the membrane with EphA3 cDNA probe. The probe spans 61 bp to 1,692 bp of EphA3 cDNA and shows a 7-kb transcript in both cell lines. (A) LK63 mRNA; (B) 293T total RNA; (C) 293TmRNA.

Northern analysis of EphA3 expression in LK63hi and 293T cell lines. Hybridization of the membrane with EphA3 cDNA probe. The probe spans 61 bp to 1,692 bp of EphA3 cDNA and shows a 7-kb transcript in both cell lines. (A) LK63 mRNA; (B) 293T total RNA; (C) 293TmRNA.

A similar pattern of promoter activity was observed in both cell lines tested. Deletion of the genomic fragment to −346 bp maintained core promoter activity. However, further 5′ deletion to −260 bp reduced the promoter activity to almost background levels. These data suggest that the region containing EphA3 gene core promoter extends to −346 bp from the TIS. The sequence of this region was analyzed using a database search program (ANGIS) for matches with known transcription factor binding sites. No consensus promoter elements, including TATA or CCAAT boxes, were identified. In all cases, the same level of basal promoter activity was observed in both 293T and Raji cell lines, despite the marked difference in endogenous EphA3 expression.

Analysis of DNA methylation state of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene in hematopoietic cell lines.

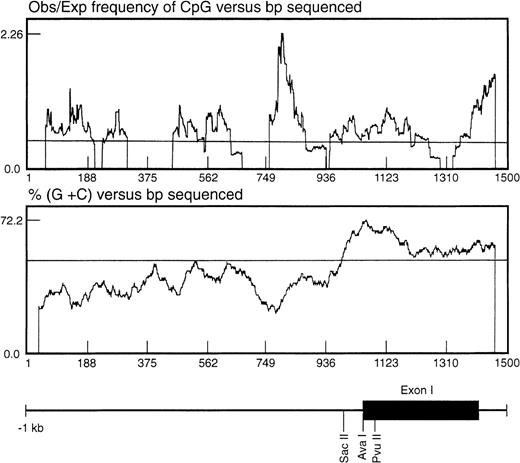

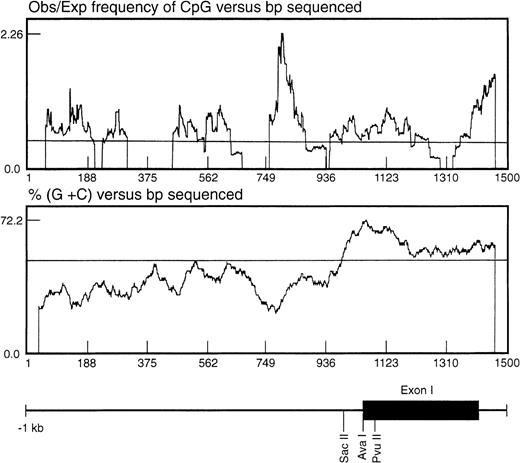

In seeking an explanation for the marked differences in expression level despite the apparently constitutive activity of the basal promoter, we noted that the region surrounding the TIS was CpG-rich. One important mechanism in regulating gene expression is methylation of the cytosine ring within the CpG sequence found associated with the promoter or coding regions of the gene.24 The CpG distribution within the 1.4-kb genomic fragment was statistically analyzed as described by the method of Gardiner-Garden and Frommer25 (Fig 5). In this analysis, a CpG-rich region is defined as stretches of DNA in which both the moving average of percent G + C is greater than 50 and the moving average of observed/expected CpG is greater than 0.47. Using these parameters, a significant CpG-rich region was located 3′ to the EphA3 core promoter region, starting from about −260 bp upstream from the TIS and extending into the first intron (Fig5).

Analysis of the distribution of CpG dinucleotides at the 5′ end of the EphA3 gene. The ratio observed/expected by chance (obs/exp) 5′-cytosine/guanine (CpG) was calculated as described by Gardiner-Garden and Frommer.25 A moving average value for percent G + C and for obs/exp CpG was calculated for each sequence using a 79-bp window moving across the sequence at 1-bp intervals. The CpG-rich regions were defined as stretches of DNA in which both the moving average of percent G + C was greater than 50 and the moving average of obs/exp CpG was greater than 0.47. Shown beneath the graph is the relative position of the EphA3 gene 5′ upstream region, first exon and part of the first intron. The positions of the enzyme restriction sites, SacII, AvaI, andPvuII, within the 1.4-kb genomic fragment are shown. These sites were used for Southern analysis of the DNA methylation state.

Analysis of the distribution of CpG dinucleotides at the 5′ end of the EphA3 gene. The ratio observed/expected by chance (obs/exp) 5′-cytosine/guanine (CpG) was calculated as described by Gardiner-Garden and Frommer.25 A moving average value for percent G + C and for obs/exp CpG was calculated for each sequence using a 79-bp window moving across the sequence at 1-bp intervals. The CpG-rich regions were defined as stretches of DNA in which both the moving average of percent G + C was greater than 50 and the moving average of obs/exp CpG was greater than 0.47. Shown beneath the graph is the relative position of the EphA3 gene 5′ upstream region, first exon and part of the first intron. The positions of the enzyme restriction sites, SacII, AvaI, andPvuII, within the 1.4-kb genomic fragment are shown. These sites were used for Southern analysis of the DNA methylation state.

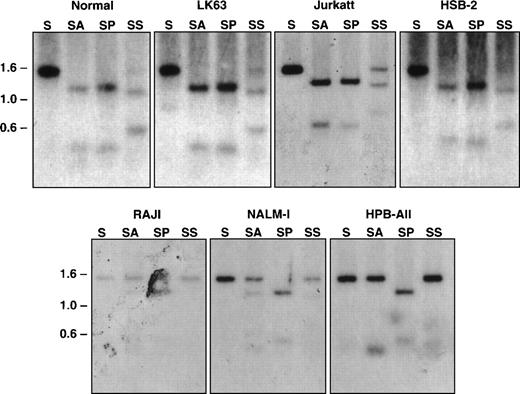

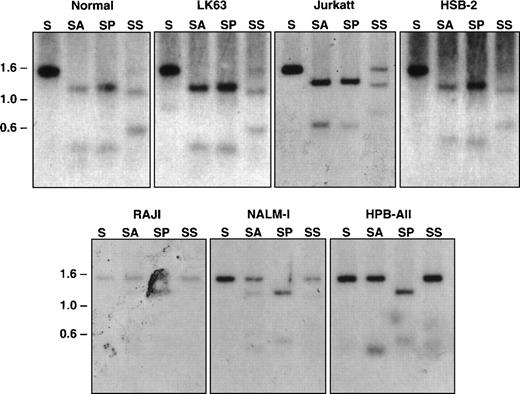

Restriction enzymes that recognize CpG-containing sequence and only cleave nonmethylated DNA were used to examine the methylation state of this CpG-rich region of the EphA3 gene in normal blood and tumor cell lines were either positive or negative for EphA3 expression (Table1).13 14 Equal quantities of DNA from each were then digested with either SacI alone or in combination with the methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes, AvaI and SacII. As a positive control, double digests of SacI and PvuII were also performed. The digests were subjected to Southern blot analyses using the 1.4-kb SacI genomic fragment as a probe for hybridization. As shown in Fig 6, the expected 1.4-kb and a 1.1-kb band were detected in all samples with a single SacI digest and with double SacI/PvuII digests, respectively. The DNA samples that were completely digested byAvaI, shown by the 1.1-kb band on the Southern blots, were from LK63, Jurkatt, and HSB-2 cell lines, all of which express EphA3 mRNA. Both 1.4-kb and 1.1-kb bands were observed in the SacII digests of these samples, indicating this methyl-sensitive enzyme can only partially digest the DNA in these cell lines. These results imply that the restriction sites are completely or partially demethylated within the DNA isolated from EphA3-expressing tumor cell lines. In contrast, the EphA3-negative cell lines, Raji, Nalm-1, and HPB-ALL cells, showed a predominant 1.4-kb band with either AvaI or Sac II digests, indicating that these sites are methylated in these cell lines. Taken together, it appears that the level of EphA3 expression in these tumor cell lines are correlated with the state of DNA methylation in this region. Consistent with this observation, Southern blot analysis of the EphA3-positive 293T cell line also showed the same restriction pattern with the methyl-sensitive enzymes as LK63 (data not shown).

Southern blot analysis of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene in normal human peripheral blood and tumor cell lines. Samples shown in the top panel all express the EphA3 gene and samples shown in the bottom panel are EphA3 negative. LK63 and Nalm-1 are pre-B cell lines and Raji is a B-cell line. Jurkatt, HSB-2, and HPB-ALL are T-cell lines. Genomic DNA (10 μg) from each sample was digested withSacI (S), or double digested with SacI and AvaI (SA), SacI and PvuII (SP), and SacI andSacII (SS). AvaI and SacII are methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes. Digests were incubated overnight at 37°C, run on a 1% agarose gel, and transferred to a Zetaprobe membrane. The membrane was hybridized with the 1.4-kb SacI genomic fragment containing the EphA3 promoter.

Southern blot analysis of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene in normal human peripheral blood and tumor cell lines. Samples shown in the top panel all express the EphA3 gene and samples shown in the bottom panel are EphA3 negative. LK63 and Nalm-1 are pre-B cell lines and Raji is a B-cell line. Jurkatt, HSB-2, and HPB-ALL are T-cell lines. Genomic DNA (10 μg) from each sample was digested withSacI (S), or double digested with SacI and AvaI (SA), SacI and PvuII (SP), and SacI andSacII (SS). AvaI and SacII are methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes. Digests were incubated overnight at 37°C, run on a 1% agarose gel, and transferred to a Zetaprobe membrane. The membrane was hybridized with the 1.4-kb SacI genomic fragment containing the EphA3 promoter.

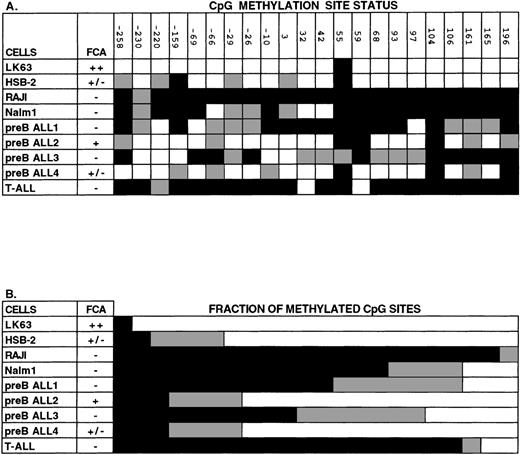

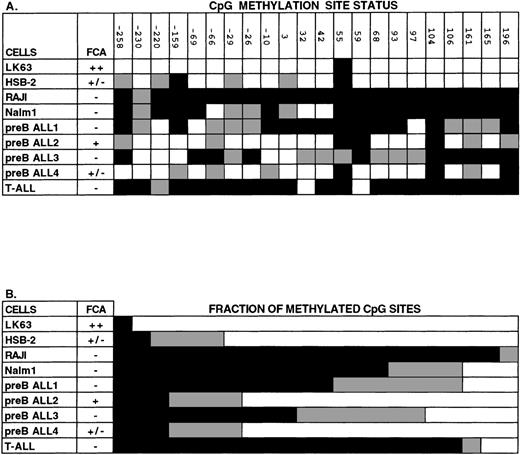

The methylation state of DNA within this region was further examined by bisulfite genomic sequencing.22,23 26 Genomic DNA was treated with bisulfite under conditions where cytosine is converted to uracil, but 5-methylcytosine remains unconverted. A 676-bp region of the modified DNA surrounding the TIS was PCR amplified using strand-specific primers. The sequence contains 22 CpG dinucleotides; the percentage of these sites that did not show C → T conversion was used as a measure of DNA methylation. As shown in Fig 7, in the EphA3-negative cell lines Raji and Nalm-1 the level of CpG methylation within this amplified region was 95% and 68%, respectively. In contrast, analysis of this region in LK63 cells found only 1 methylated CpG dinucleotide and the remainder were unmethylated. Similarly, only 9% of the CpG dinucleotides were methylated and 73% were unmethylated in the EphA3 expressing cell line, HSB-2. The remaining 18% of CpG dinucleotides were partially methylated because the sequence of bisulfite-modified DNA showed both cytosine and thymine nucleotides present in the one position.

Analysis of CpG methylation in human hematopoietic cell lines and in leukemic blood samples using sequencing of bisulfite-treated genomic DNA. The region of DNA analyzed with this technique was from the 5′ CpG-rich region of the Epha3 gene, which normally contains 22 individual CpG sites. (A) The methylation status of each CpG site. The positions of these 22 CpG sites are numbered relative to the TIS. (B) The proportion of CpG sites found methylated, unmethylated, or partially methylated. Methylated cytosines (black) remain unchanged with bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA, whereas unmethylated cytosines (white) are converted to uracil and then amplified as thymic. Some sequences showed both cytosine and thymine nucleotides present in the one position (gray), suggesting that these cytosines were partially methylated. EphA3 expression by FCA is shown as being either strongly positive (++), weakly positive (+/−), or negative (−). LK63, HSB-2, Raji, and Nalm-1 are all hematopoietic cell lines. Other samples were taken from patients with pre-B or T-ALL leukemias.

Analysis of CpG methylation in human hematopoietic cell lines and in leukemic blood samples using sequencing of bisulfite-treated genomic DNA. The region of DNA analyzed with this technique was from the 5′ CpG-rich region of the Epha3 gene, which normally contains 22 individual CpG sites. (A) The methylation status of each CpG site. The positions of these 22 CpG sites are numbered relative to the TIS. (B) The proportion of CpG sites found methylated, unmethylated, or partially methylated. Methylated cytosines (black) remain unchanged with bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA, whereas unmethylated cytosines (white) are converted to uracil and then amplified as thymic. Some sequences showed both cytosine and thymine nucleotides present in the one position (gray), suggesting that these cytosines were partially methylated. EphA3 expression by FCA is shown as being either strongly positive (++), weakly positive (+/−), or negative (−). LK63, HSB-2, Raji, and Nalm-1 are all hematopoietic cell lines. Other samples were taken from patients with pre-B or T-ALL leukemias.

In addition to hematopoietic cell lines, the methylation state of the EphA3 CpG-rich region was examined in samples taken from patients with high blast count leukemias (counts between 10,000 to 50,000) (Fig 7). In some samples, assignment at certain positions was difficult, probably due to mixing of DNA from both leukemic and normal cells. However, in 3 samples in which EphA3 expression was not detected by FCA (preB ALL samples 1 and 3 and a T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia [T-ALL]), more than half of the 22 CpG dinucleotides analyzed were found to be methylated. In contrast, in 2 cases in which EphA3 was detected, only 3 of the CpG dinucleotides were methylated. Altogether, these findings are consistent with the results obtained by Southern blot analyses, and are in support of a tight correlation between EphA3 expression analyses and status of DNA methylation within the 5′ region of EphA3 gene.

A single CpG dinucleotide, located 55 bp from the TIS, was found to be consistently methylated in all cell lines analyzed. Adjacent to this dinucleotide was a CpNpG site that was found unaltered in all samples and therefore assumed to be methylated. Sequence analysis of nucleotides 46 bp to 68 bp surrounding the CpNpG site shows that this region is palindromic and, therefore, forms a hair-pin loop structure that may prevent complete reaction with bisulfite. However, methylation of CpNpG within mammalian cells has also been previously reported.27 28

DNA methylation of EphA3 gene 5′ upstream sequence in normal human tissues.

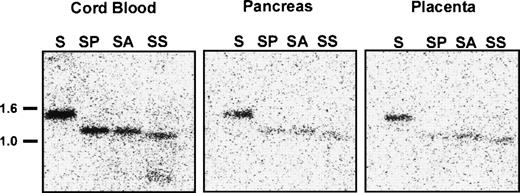

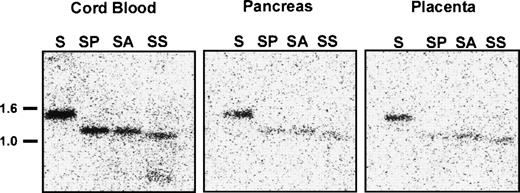

To determine whether DNA methylation regulates EphA3 transcription in normal tissues, we analyzed the methylation state of the 5′ upstream EphA3 gene sequence from various samples of normal human tissue which show different levels of EphA3 expression. These samples included lymphocytes and monocytes isolated from cord blood, in addition to adult pancreas, placenta (Fig8), and thymus tissues (M.D., unpublished data, November 1998). Low levels of EphA3 message can be detected in lymphocytes and thymus by PCR, but no staining is detectable by immunofluorescence using the IIIA4 MoAb.13,14 A Northern analysis of a human tissue blot showed expression in placenta, but no detectable expression in pancreas or kidney.29 Genomic Southern analysis showed complete digestion of DNA with the methyl-sensitive enzymes, AvaI and SacII, in all samples analyzed (Fig 8). Thus, in contrast to the results obtained from the hematopoietic tumor cell lines and tumor samples analyzed, these results imply that, despite the virtually undetectable levels of expression in these tissues, the sequence proximal to the EphA3 promoter is unmethylated in normal adult human tissues.

Southern blot analysis of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene in normal human samples of lymphocytes and monocytes isolated from cord blood, adult pancreas, and placental tissues. Genomic DNA (10 μg) from each sample was digested withSacI (S) or double digested with SacI and AvaI (SA), SacI and PvuII (SP), and SacI andSacII (SS). AvaI and SacII are methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes. The Southern blot was hybridized with the 1.4-kbSacI genomic fragment containing the EphA3 promoter.

Southern blot analysis of the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene in normal human samples of lymphocytes and monocytes isolated from cord blood, adult pancreas, and placental tissues. Genomic DNA (10 μg) from each sample was digested withSacI (S) or double digested with SacI and AvaI (SA), SacI and PvuII (SP), and SacI andSacII (SS). AvaI and SacII are methyl-sensitive restriction enzymes. The Southern blot was hybridized with the 1.4-kbSacI genomic fragment containing the EphA3 promoter.

DISCUSSION

In this report we describe studies seeking to determine the mechanism of control of EphA3 expression in human tumors. Flow cytometric analysis was used to determine receptor numbers (Table 1), demonstrating that some hematopoietic cell lines appear to not express EphA3 at all while other lines from the same cell lineage show strong expression. Thus, LK63, a pre-B cell line, contained the highest levels of EphA3, whereas no expression was detected in Lila-1, Nalm-1, or Raji cells which are pre-B and B-cell lines, respectively. A range of EphA3 expression is also found in different T-cell lines. Moderate to high levels of EphA3 was shown in the T-cell lines, JM, Jurkat, and MOLT4. In other T-cell lines, HSB-2 showed weak EphA3 expression, whereas no EphA3 was detected in HPB-ALL cells. No EphA3 expression was detected in the monocytic and erythroid cell lines tested. Real-time PCR analysis was used to quantitate mRNA levels in 4 of the cell lines and showed an excellent correlation between mRNA content and receptor number, thus allowing us to infer transcriptional activity from protein expression data. In the mouse and chicken, EphA3 is highly expressed during embryogenesis but, as in humans, in adult animals EphA3 is restricted to expression in the brain.16 17 Thus, expression of EphA3 in the adult animal is much lower than that observed in a subset of tumors, perhaps suggesting that these lines have reactivated embryonic regulators of EphA3 gene expression.

To determine how the EphA3 gene is regulated, we sought to identify and characterize the 5′ upstream regulatory region of the EphA3 gene. A 1.4-kb SacI fragment isolated from a genomic clone containing exon 1 and 5′ upstream sequence of the EphA3 gene was analyzed in detail. Various deletion constructs driving the luciferase reporter were used to identify the basal promoter region of 86 bp located at −348 bp to −262 bp upstream from the transcription initiation site. These studies suggest that the basal promoter is equally active in both EphA3-negative and -positive cells. The minimal promoter region of the EphA3 gene lacked consensus TATA or CAAT-elements and the 3′ region proximal to the EphA3 promoter was shown to be GC-rich. These structural features have also been found in many tissue-specific gene promoters. For example, the synapsin I, synapsin II, nerve growth factor receptor, and polysialic acid synthase genes are all neuron-specific, TATA-less promoters that are associated with GC-rich domains and have a single transcription initiation start site.30-33

Further analysis of this region showed a significant CpG-rich region within the 5′ region of the EphA3 gene. We explored the possibility that methylation acts to regulate EphA3 expression. It was found that the level of methylation within the 5′ upstream EphA3 gene region correlated with the level of EphA3 gene and protein expression in the tumor lines. Similar results were also obtained in blood samples taken from patients with high blast count leukemias. Many studies of genes associated with CpG-rich sequences have described the repression of transcription by DNA methylation.24 Two molecular mechanisms have been proposed to explain how this repression may occur. One possibility is that methylation of CpG dinucleotides within the binding sites of transcription factors may directly prevent the protein/DNA interaction. This mechanism of repression has been observed for several transcription factors, including AP-2, adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic phosphate (cAMP)-responsive enhancer, activating transcription factor (ATF)-like factor, and retinoblastoma binding factor 1.34-36 However, some genes are found to be inhibited by methylation in a manner that is not dependent on methylation of the binding sites of transcription factors,37,38 suggesting an indirect mechanism of transcriptional repression. Evidence for an indirect repression was obtained with the cloning of factors, such as MeCP-1 and MeCP-2, that bind to methylated CpGs regardless of the sequence context.39 40 This binding may alter the chromatin structure so that the gene is inaccessible to the active transcriptional machinery.

When normal tissues were examined, the correlation between DNA methylation levels and EphA3 expression observed in tumors was not seen. Although almost all of the normal tissues examined showed relatively low levels of EphA3 transcription, the EphA3 gene was nonmethylated. Thus, in normal tissues, the strong EphA3 expression in embryonic tissues and minimal expression in adult tissues13,14,29 must be explained by other factors such as observed with EphA2 and EphA4.41-43 In both the EphA241 and EphA443 genes, enhancer/promoter elements that bind homeodomain proteins were identified and were shown to be sufficient for embryonic tissue-specific expression. Thus, the regulation by DNA methylation found within certain tumor cell lines seems to be a result of neoplastic transformation rather than being a normal mechanism of regulation of EphA3 transcription. Aberrant DNA methylation has been associated with oncogenesis. For example, there are reports which show that abnormal hypermethylation events may occur, which result in the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and growth inhibitory genes, thereby contributing to neoplastic transformation.44-46

In summary, hematopoietic tumors show great variation in EphA3 expression. Clearly, some tumors show increased expression of Eph receptors compared with that seen in normal adult tissues, possibly as a result of activation of developmentally regulated transcription factors. Such overexpression may contribute to the initial transformation events leading to neoplasia.47 However, other tumors clearly show tumor-specific silencing of the EphA3 gene through DNA methylation. In considering how such silencing might be selected for in some tumors, we note that the normal function of these receptors is to prevent free movement of cells into regions expressing their high-affinity cognate ligand (ephrin).9,48 49 Thus, we suggest that in tumors where the need for EphA3 overexpression to maintain the transformed phenotype has become redundant, silencing of EphA3 through DNA methylation may be a late event allowing free movement of tumor cells and, hence, contributing to the development of the metastatic phenotype.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Toni Antalis for discussions and critical comments on the manuscript. We also thank David Elliot for giving us invaluable advice on techniques.

Supported by the Queensland Cancer Fund, National Health and Medical Research Council, and Leukaemia Foundation of Queensland. A.H. is supported by the Dr Mildred Scheel Stiftung.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Andrew Boyd, MD, PhD, Queensland Institute of Medical Research, The Bancroft Centre, PO Royal Brisbane Hospital, Herston 4029, Queensland, Australia; e-mail: andrewBo@qimr.edu.au.