THE CELL SURFACE glycoprotein CD34 has been the focus of intense interest ever since its discovery on a small fraction of human bone marrow cells.1 The CD34+population appears responsible for most, if not all, of the hematopoietic activity in bone marrow, including colony formation in short-term assays,1 the maintenance of long-term in vitro cultures,2 and the expansion and differentiation of blood cell subsets in immunocompromised mice.3 Successful engraftment of baboons with bone marrow highly enriched for CD34+ cells4 led to the widespread use of CD34-enriched populations in human transplantation. In general, patients transplanted with marrow or mobilized peripheral blood enriched for CD34+ cells engraft rapidly and seem to have fewer transplant-related complications.5-8 Devices for the enrichment of CD34+ cells have been a commercial success and the object of infamous corporate battles.

However, niggling worries about the phenotype of the most primitive hematopoietic stem cells began to surface about 3 years ago and now challenge the preeminence of CD34 as a stem cell marker. Experiments on bone marrow from both mice and humans suggested that at least some primitive progenitors lacked CD34 and were capable of generating CD34+ stem cells.9-12 This new concept stirred enormous controversy among investigators who had taken CD34 from the bench to the bedside, guided by ostensibly sound scientific principles. It challenged not only the interpretation of a wealth of experimental data on the potency of CD34+ cells (and the lack, thereof, of CD34− cells), but also the wisdom of applying them in clinical practice. The tacit suggestion was that researchers and clinicians alike may have been unwittingly discarding the very best stem cells.

After overcoming their initial surprise, hematologists worldwide undertook to address the critical questions surrounding this novel hypothesis. In this issue of BLOOD, Sato, Laver, and Ogawa13 present an elegant study on the expression of CD34 on long-term reconstituting stem cells in the mouse. Their report was a pleasure to read due to the simplicity of the experiments, the strength of the conclusions, and the clarity of the prose.

In the mouse, one has the luxury of testing the activity of hematopoietic stem cells in the most rigorous way: by transplanting test populations into myeloablated recipients and examining peripheral blood for the progeny of test cells over the course of many months. Because of the plethora of inbred mouse strains, cell populations differing at only 1 or 2 genetic loci can be readily transferred from one strain to another, thereby reducing the number of potentially confounding variables. The marker du jour is CD45 (still often called by its older murine nomenclature, Ly-5), of which 3 alleles exist that differ by a few amino acids, each being recognized by specific monoclonal antibodies.14 Because CD45 is expressed on all nucleated peripheral blood cells, it can be used to distinguish progeny of test populations by flow cytometry analysis for the CD45 allele in conjunction with lineage markers.

Sato et al13 used this powerful system to revisit the question of whether CD34 is expressed on primitive murine hematopoietic stem cells, as defined exclusively by bone marrow transplantation. They purified CD34+ and CD34− cells from Ly-5.2 mice and transplanted these subsets into sublethally irradiated Ly-5.1 recipients. They also administered to the recipients a small dose of compromised Ly-5.1 marrow (bone marrow depleted of stem cell activity by serial transplantation), providing short-term peripheral blood cell production and perhaps other cells and factors that may support the engraftment of sorted cells.

When stem cells from normal mice were sorted, the investigators observed clear segregation of stem cell activity into the CD34− population. At 2 and 5 months after transplantation, all mice transplanted with small numbers of CD34− cells showed high numbers of Ly-5.2 progeny. Mice transplanted with 5 times as many CD34+ stem exhibited little to no repopulation from the sorted cells. The results were dramatically different when the investigators used bone marrow from mice that were treated 2 days earlier with 5-fluoruracil (5-FU). Toxic to dividing cells, 5-FU rapidly depletes the marrow of committed progenitors and appears to recruit dormant hematopoietic stem cells into cycle.15 When the investigators sorted stem cells from these animals, using a strategy identical to that applied to normal marrow, they found the stem cell activity to be fairly evenly distributed between the CD34− and CD34+compartments, regardless of whether the recipients were examined at short (2-month) or long (8-month) intervals after transplantation. These results suggested that CD34 on quiescent stem cells might be upregulated in response to proliferation signals and, as such, may be a marker of activated stem cells. In pursuit of this idea, Sato et al13 stimulated normal CD34− stem cells in vitro with stem cell factor and interleukin-11. After 1 week of culture, they observed a 1,000-fold expansion of the CD34− population and the acquisition of a CD34+ phenotype by 75% of the cells. When the CD34+ cells and CD34− cells were sorted from these cultures and transplanted into mice, only the latter gave rise to differentiated progeny. These results showed that CD34− stem cells can generate CD34+ cells and that at least some of the new CD34+ cells are long-term reconstituting stem cells, because they were associated with high level engraftment up to 5 months after transplantation. The remaining cultured CD34− cells had no apparent stem cell activity in vivo.

Finally, the investigators asked whether CD34+ stem cells could revert to a CD34− phenotype. Taking bone marrow from mice that had been transplanted with CD34+ stem cells derived from 5-FU–treated donors, they sorted CD34+ and CD34− stem cells and transplanted them into secondary recipients. At 2 and 5 months posttransplantation, they found that only the CD34− stem cells had generated progeny. Thus, some of the stem cells originally expressing CD34 in the 5-FU–treated donor marrow lost the marker after transplantation.

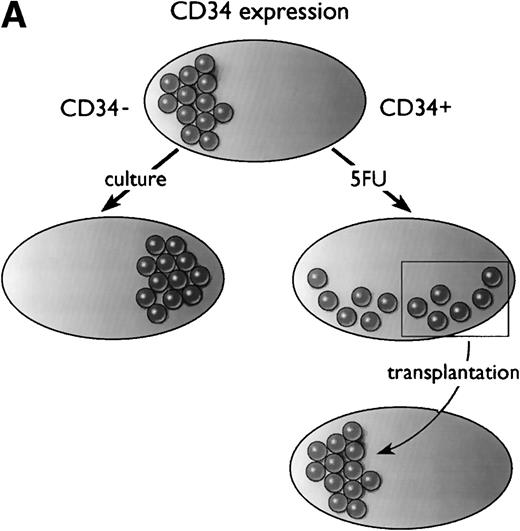

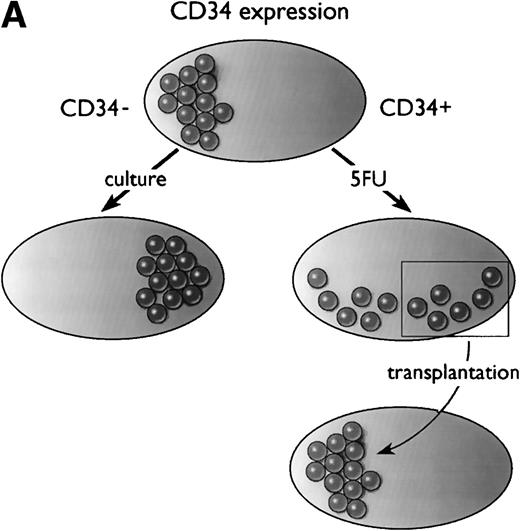

In summary, as diagrammed in Fig 1A, Ogawa’s group has shown that a population of primitive, transplantable hematopoietic stem cells starts out as CD34− in normal mice. At least some of these CD34− stem cells convert to a CD34+ phenotype upon activation by 5-FU (or after culture), and after transplantation, the CD34+ stem cells revert to a CD34− phenotype.

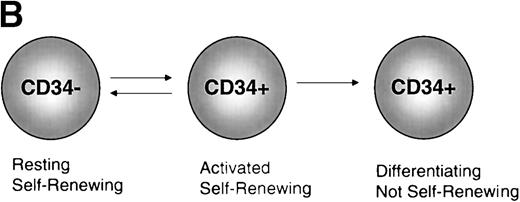

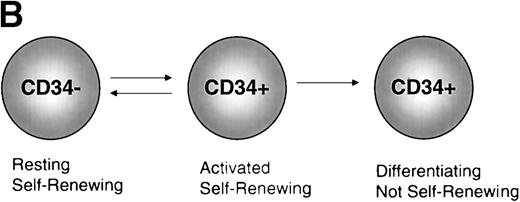

Models of CD34 expression in bone marrow. (A) Diagram of conclusions from the current paper by Sato et al.13 The spheres represent arbitrary units of hematopoietic stem cell-repopulating activity, as measured by long-term bone marrow transplantation in mice. In normal murine bone marrow, the long-term repopulating activity is found entirely in the CD34−/lowcompartment. During culture, the CD34− stem cells expand and acquire CD34, and the CD34+ cells contain all detectable hematopoietic repopulating activity. After 5-FU treatment, this activity is distributed between CD34+ and CD34− subsets of bone marrow. When bone marrow is taken from mice previously engrafted with CD34+ bone marrow derived from 5-FU–treated mice, the repopulating activity, measured in secondary recipients, is restricted to the CD34−/low stem cell fraction. (B) Model of CD34 expression on murine hematopoietic stem cells. Resting stem cells from normal mice express little or no CD34, have a limited capacity for self-renewal, and can convert to a CD34+ phenotype upon activation. The CD34+ stem cells can self-renew as well as convert to a resting CD34− phenotype. Alternatively, they may begin to differentiate, at which point they presumably lose their potential for self-renewal.

Models of CD34 expression in bone marrow. (A) Diagram of conclusions from the current paper by Sato et al.13 The spheres represent arbitrary units of hematopoietic stem cell-repopulating activity, as measured by long-term bone marrow transplantation in mice. In normal murine bone marrow, the long-term repopulating activity is found entirely in the CD34−/lowcompartment. During culture, the CD34− stem cells expand and acquire CD34, and the CD34+ cells contain all detectable hematopoietic repopulating activity. After 5-FU treatment, this activity is distributed between CD34+ and CD34− subsets of bone marrow. When bone marrow is taken from mice previously engrafted with CD34+ bone marrow derived from 5-FU–treated mice, the repopulating activity, measured in secondary recipients, is restricted to the CD34−/low stem cell fraction. (B) Model of CD34 expression on murine hematopoietic stem cells. Resting stem cells from normal mice express little or no CD34, have a limited capacity for self-renewal, and can convert to a CD34+ phenotype upon activation. The CD34+ stem cells can self-renew as well as convert to a resting CD34− phenotype. Alternatively, they may begin to differentiate, at which point they presumably lose their potential for self-renewal.

These data suggest that CD34 may be a marker of activated stem cells, but not necessarily all stem cells. This activation may represent self-renewal or proliferation linked to differentiation (Fig 1B), an interpretation supported by anecdotal data from other systems. When the expression pattern of CD34 was investigated in the developing mouse embryo, the antigen was found to be expressed on vascular endothelial cells, particularly at the growing tips of sprouting vessels, where the most active proliferation was occurring.16 CD34 expression is also upregulated on rat-liver oval cells, a presumptive liver stem cell, during hepatic regeneration.17 Nevertheless, this CD34+ stage of stem cells is clearly not obligatory for differentiation, because mutant mice lacking CD34 have normal steady-state numbers of peripheral blood cells, although they have a reduced number of hematopoietic progenitors (the hematopoietic compartment undergoing the most extensive proliferation).18

If further experimentation bears out this intriguing link between CD34 expression and stem cell activation or self renewal, it will be important to determine the mechanisms of CD34 regulation. Fackler et al19 showed that surface expression of human CD34 rapidly increased upon protein kinase C-mediated hyperphosphorylation of intracellular CD34. Thus, it will also be interesting to determine whether quiescent CD34− stem cells have intracellular stores of CD34 message or protein that would allow such rapid activation.

This current study is the capstone on a series of studies on mouse hematopoietic stem cells that have clearly shown that most normal quiescent murine stem cells express very low levels of the CD34 marker.9,10,20 Some of the early contradictory reports21,22 may be explained by the observation that resting stem cells express low but detectable levels of CD34 as shown when defined by antibody-independent methods.10 This low-level of expression can cause overlap in purified subsets, resulting in stem cell activity being measured in all populations.

What are the implications of this work for human stem cell biology? If the human CD34 expression pattern mirrors that of the mouse, we may expect to find substantial stores of quiescent CD34−hematopoietic stem cells tucked away in the bone marrow. Likewise, we would expect their CD34+ counterparts to be activated with regard to proliferation and differentiation, possibly explaining why the hematopoietic activity of CD34+ stem cells has been vastly easier to measure in vitro and in vivo. Recent work indicates that human CD34− stem cells may indeed exist.10-12 Such cells are likely to be quiescent, because only 1 group has reported significant hematopoietic activity by them in conventional assays,12 leading one to ask how they can be efficiently stimulated.

We might also expect that human CD34− and CD34+ stem cells are freely interconvertible. If their identities do converge in vivo, perhaps we need not worry whether we should work with CD34− or CD34+ stem cells (as long as we are working with true stem cells: CD34 is primarily expressed on committed progenitors). Perhaps the population that is easiest to use and manipulate will prove to be the best choice, at least as regards the clinic. Of course, it is still quite possible that human CD34 expression does not entirely mimic that in the mouse in one or more ways. The populations may not be interconvertible, or the CD34− population may not represent an appreciable natural reservoir for CD34+ cells. Only time, and further investigation, will tell.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Margaret A. Goodell, PhD, Center for Cell and Gene Therapy, Baylor College of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, N1030, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: Goodell@bcm.tmc.edu.