Abstract

Eotaxin and other CC chemokines acting via CC chemokine receptor-3 (CCR3) are believed to play an integral role in the development of eosinophilic inflammation in asthma and allergic inflammatory diseases. However, little is known about the intracellular events following agonist binding to CCR3 and the relationship of these events to the functional response of the cell. The objectives of this study were to investigate CCR3-mediated activation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinase-2 (ERK2), p38, and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in eosinophils and to assess the requirement for MAP kinases in eotaxin-induced eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) release and chemotaxis. MAP kinase activation was studied in eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils (more than 97% purity) by Western blotting and immune-complex kinase assays. ECP release was measured by radioimmunoassay. Chemotaxis was assessed using Boyden microchambers. Eotaxin (10−11 to 10−7 mol/L) induced concentration-dependent phosphorylation of ERK2 and p38. Phosphorylation was detectable after 30 seconds, peaked at about 1 minute, and returned to baseline after 2 to 5 minutes. Phosphorylation of JNK above baseline could not be detected. The kinase activity of ERK2 and p38 paralleled phosphorylation. PD980 59, an inhibitor of the ERK2-activating enzyme MEK (MAP ERK kinase), blocked phosphorylation of ERK2 in a concentration-dependent manner. The functional relevance of ERK2 and p38 was studied using PD98 059 and the p38 inhibitor SB202 190. PD98 059 and SB202 190 both caused inhibition of eotaxin-induced ECP release and chemotaxis. We conclude that eotaxin induces a rapid concentration-dependent activation of ERK2 and p38 in eosinophils and that the activation of these MAP kinases is required for eotaxin-stimulated degranulation and directed locomotion.

Eosinophils are crucial effector cells in the inflammatory reactions associated with asthma, allergic-inflammatory diseases, and parasitic infections. Eosinophils are recruited to sites of inflammation by locally released chemotactic agents. The CC chemokines eotaxin, RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted), and monocyte chemotactic protein-2, -3, and -4 are potent stimulators of eosinophil chemotaxis. They also induce mediator release from eosinophils and are believed to play an integral role in the development of eosinophilic inflammation.1-10 CC chemokines are generally promiscuous and bind to more than 1 CC chemokine receptor (CCR). The exceptions appear to be eotaxin and eotaxin-2, which bind exclusively to CCR3.11-13 Compared to other CCRs, CCR3 is expressed in high numbers on eosinophils.14 Blocking of CCR3 has been shown to inhibit eosinophil response to eotaxin, RANTES, and monocyte chemotactic protein-2, -3, and -4 by more than 95%, indicating that CCR3 is the most important eosinophil receptor for these chemokines.15 Both CCR3 and the other CCRs belong to the family of serpentine receptors. These receptors traverse the plasma membrane 7 times and are linked to heterotrimeric G proteins. CCR3 is sensitive to pertussis toxin, indicating linkage to Gi. Further, agonist binding to CCR3 has been demonstrated to induce an increase of the intracellular Ca++-concentration.11,12 14 Apart from the above, the signaling pathways through CCR3 and the involvement of relevant signaling molecules in the functional response of the cell are unknown.

We hypothesize that mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases play an important role in CCR3 signaling. In the present study, we investigated the involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-2 (ERK2), p38, and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in the signal transduction mechanism of eosinophil degranulation and chemotaxis.

Materials and methods

Donors

Peripheral venous blood was obtained from donors with mild to moderate eosinophilia (4%-12%) after written informed consent. Some of the blood donors had mild seasonal allergic rhinitis and were taking antihistamines on an as needed basis. These subjects refrained from taking medications 24 hours before blood donation. Other blood donors were clinically healthy and were not taking any medications.

Eosinophil purification

Eosinophils were isolated using a modification of the method described by Hansel et al.16 Briefly, peripheral blood was sedimented with 6% hydroxyethyl starch. Eosinophils were further isolated by centrifugation of the leukocyte-rich phase through 1.088-g/mL Percoll (Pharmacia and Upjohn, Uppsala, Sweden) gradients. Contaminating erythrocytes were lysed with distilled water (1 minute, 0°C), and neutrophils were removed with anti-CD16 immunomagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergish Gladbach, Germany). Eosinophils (more than 97% purity) were resuspended in Hybri-care medium (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) or RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and transferred to microfuge tubes coated with 3% HSA (human serum albumin).

Stimulation, preparation of cytosolic extracts, and immunoprecipitation

PD98 059 (New England BioLabs, Beverly, MA) and SB202 190 (CalBiochem, La Jolla, CA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The highest final concentration of DMSO was 0.1%. Where appropriate, eosinophils were preincubated with PD98 059 for 30 minutes at 37°C, monoclonal anti-CCR3 blocking antibody (clone 7B11, a gift from Dr Poul D. Ponath, LeukoSite Inc, Cambridge, MA), isotype-specific control antibody (clone GE-1, Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) for 30 minutes on ice, or pertussis toxin (Sigma) for 1 hour at 37°C. For detection of ERK2 with anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-ERK2 antibodies, 2 × 106 eosinophils were incubated with human recombinant eotaxin (eotaxin-1, Peprotech, Rocky Hills, NJ) or medium at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 4 volumes of ice-cold 1.25 × lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4; 1.25% NP-40; 313 mM NaCl; 1.25 mM EDTA; 0.625 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride; 1.25 μg/mL aprotinin; 1.25 μg/mL leupeptin; 1.25 μg/mL pepstatin; 1.25 mM Na3VO4; and 1.25 mM NaF) and immediate transfer to ice. After incubation on ice for 20 minutes, the detergent-insoluble materials were sedimented by centrifugation (12 000g, 4°C). The supernatants were precleared by incubation with 20 μL of Protein A/G Plus agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The protein concentration of the cytosolic extracts was determined using the microBCA assay (Pierce Chemical Co, Rockford, IL), and the protein content (200 μg) and concentration of the samples was equalized. For immunoprecipitation, the samples were incubated with 7 μg/mL of anti-ERK2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour at 4°C, followed by incubation with 20 μL of Protein A/G Plus agarose for 2 hours at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed 4 times with ice-cold 1 × lysis buffer and boiled with 20 μL of 2 × Laemmli buffer for 4 minutes. Samples used for Western blotting were denatured prior to immunoprecipitation by boiling with 6% glycerol; 0.8% β-mercaptoethanol; 1.7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS); 58 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; and 0.002% bromphenol blue for 4 minutes.

For detection of ERK2, p38, and JNK with antibodies directed against the dual threonine/tyrosine–phosphorylated MAP kinases, eosinophils (106 per sample) were stimulated and lysed as described above. The cytosolic extracts were boiled with equal volumes of 2 × Laemmli buffer for 4 minutes.

SDS gel electrophoresis and Western blotting

SDS-polyacrylamide (10%) gels were prepared according to the Laemmli protocol. The gels were blotted onto Hybond ECL membranes (Amersham Corp, Arlington Heights, IL). Excess binding sites were blocked by incubation with 10% BSA (bovine serum albumin) in TBS-T 20 mM Tris base, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.6, for 1 hour. For detection of ERK2 and JNK, the membranes were then incubated with 0.1 μg/mL of primary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature (monoclonal anti-phosphotyrosine antibody, clone 4G10, Upstate Biotechnology, Inc, Lake Placid, NY, or polyclonal anti-ERK2 antibody, monoclonal anti-phospho-ERK2 antibody, or monoclonal anti-phospho-JNK antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The membranes were washed 5 times with TBS-T, incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjungated secondary antibody (1:10 000 dilution of anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) from Sigma or 0.04 μg/mL of anti-rabbit IgG antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 20 minutes and washed 5 times with TBS-T. The blots were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Detection of p38 was performed as described above, except for the incubations with primary antibody (1:1000 dilution of polyclonal anti-p-p38, New England BioLabs) and secondary antibody (0.2 μg/mL horseradish peroxidase–conjungated anti-rabbit Ig, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), which were performed overnight at 4°C and for 1 hour at room temperature, respectively.

Immune-complex kinase assay

Immunoprecipitates of ERK2 were prepared as described above. Immunoprecipitates of p38 were prepared using anti-p38 antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The precipitates were washed 2 times in ice-cold 1 × lysis buffer and 2 times in ice-cold kinase buffer (10 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 μM Na3VO4, 500 μM dithiothreiol, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate) and incubated with 40 μL of kinase buffer containing 2.5 μM of adenosine triphosphate (ATP; Pharmacia and Upjohn), 10 μCi of γ-[32P]-ATP (Amersham), and 50 μg/mL of myelin basic protein (MBP, Sigma) for detection of ERK2 activity or 12.5 μg/mL of activating transcription factor (ATF-2, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for detection of p38 activity for 17 minutes at 30°C. After centrifugation for 6 minutes at room temperature, the reaction was stopped by boiling 30 μL of supernatant with 30 μL of 2 × Laemmli buffer. A 20-μL sample was loaded on 15% (for MBP detection) or 10% (for ATF-2 detection) SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The gels were either dried or blotted onto polyvinylidine difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp, Bedford, MA). MBP or ATF-2 phosphorylation was visualized by autoradiography.

ECP release

Ninety-six–well plates were coated with 3% HSA in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) for 2 hours at 37°C and washed 3 times with HBSS without Ca++ and Mg2+ (Life Technologies). Purified eosinophils were suspended at 5 × 105cells/mL in RPMI 1640 with 0.1% HSA. Eosinophils (5 × 104 cells/well) were preincubated with medium, PD98 059, or SB202 190 for 1 hour at 37°C and stimulated with eotaxin (10−7 mol/L) for 4 hours in a total volume of 110 μL. The cell suspensions were then transferred to microfuge tubes that had been coated with 3% HSA, and the supernatants were collected after centrifugation. The eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) concentration was measured by a radioimmunoassay kit (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Chemotaxis assay

The chemotaxis assay was performed in a 48-well Boyden microchamber (Neuro Probe, Gaithersburg, MD) technique. Briefly, eotaxin was diluted in RPMI 1640 with 0.5% pooled human serum and placed in the lower wells (25 μL) at 10−8 mol/L concentration; 50 μL of the cell suspension at 1 × 106 cells/mL were added to the upper well of the chamber, which was separated from the lower well by a 5-μm–pore-size, polycarbonate, polyvinylpyrolidone-free membrane (Nucleopore, Pleasanton, CA). The cells were freshly isolated eosinophils or eosinophils incubated with reagents as indicated. The chamber was incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% carbon dioxide. The membrane was then carefully removed, fixed in 70% methanol, and stained for 5 minutes in Coomassie brilliant blue. The cells that migrated and adhered to the lower surface of the membrane were counted from 5 fields by light microscopy. The chemotactic response to buffer (less than 20 cells/5 fields) was subtracted from that induced with eotaxin with or without the inhibitors.

Statistical analyses

ECP release and chemotaxis in the presence and absence of inhibitors was compared by ANOVA. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Eotaxin induces rapid activation of ERK2 and p38, but not of JNK, in eosinophils

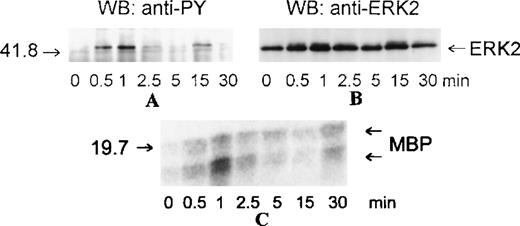

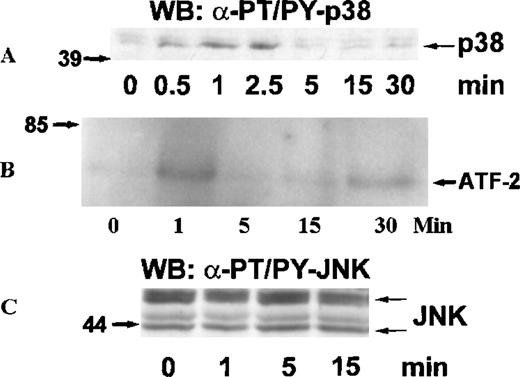

MAP kinases constitute 3 major groups of serine/threonine kinases: ERK1/ERK2, p38, and JNK.17 We examined the activation of MAP kinases by eotaxin in eosinophils. Eosinophils (more than 97% purity) were incubated with medium or stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 15, or 30 minutes. To study the activation of ERK2, cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-ERK2 antibodies. Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies revealed tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK2 reaching a maximum at about 1 minute and returning to baseline levels by 2.5 to 5 minutes (Figure 1A). Reprobing the membrane with the anti-ERK2 antibodies showed a concomitant motility shift of ERK2 (Figure 1B). To test whether tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK2 was paralleled by activation, we assessed the kinase activity of ERK2 immunoprecipitates in the immune-complex kinase assay using MBP as the substrate. The kinetics of ERK2 activation were similar to those of ERK2 phosphorylation (Figure1C). Activation of MAP kinases requires simultaneous phosphorylation of select threonine and tyrosine residues.17 To investigate the activation of p38 and JNK, cytosolic extracts of eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils were used for Western blotting with antibodies directed toward dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 and JNK. Dual phosphorylation of p38 reached a maximum at about 1 minute and returned to baseline after 2.5 to 5 minutes (Figure2A). To verify that the phosphorylation of p38 was accompanied by activation, we immunoprecipitated p38 from cytosolic extracts. The immunoprecipitates were tested in the immune-complex kinase assay using ATF-2 as the substrate. The kinetics of activation (Figure 2B) and phosphorylation of p38 were in agreement. Under basal conditions, some threonine-tyrosine phosphorylation of JNK was detected. Stimulation with eotaxin did not increase JNK phosphorylation at any of the tested time points (Figure 2C).

Kinetics of ERK2 activation in eosinophils stimulated with eotaxin.

Eosinophils were incubated with medium or stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 15, or 30 minutes. Cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with the anti-ERK2 antibody. (A) Tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK2 was detected by Western blotting (WB) with the anti-phosphotyrosine (α-PY) antibody. (B) Concomitant bandshifting was detected by reprobing the membrane with the anti-ERK2 antibody. This also verified that the tyrosine-phosphorylated band was ERK2 (n = 3). (C) ERK2 immunoprecipitates were assayed for kinase activity using MBP as the substrate. The kinase activity following eotaxin stimulation paralleled the tyrosine phosphorylation profile of ERK2. The numbers on the left side of the panels indicate the position of the molecular weight markers.

Kinetics of ERK2 activation in eosinophils stimulated with eotaxin.

Eosinophils were incubated with medium or stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 15, or 30 minutes. Cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with the anti-ERK2 antibody. (A) Tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK2 was detected by Western blotting (WB) with the anti-phosphotyrosine (α-PY) antibody. (B) Concomitant bandshifting was detected by reprobing the membrane with the anti-ERK2 antibody. This also verified that the tyrosine-phosphorylated band was ERK2 (n = 3). (C) ERK2 immunoprecipitates were assayed for kinase activity using MBP as the substrate. The kinase activity following eotaxin stimulation paralleled the tyrosine phosphorylation profile of ERK2. The numbers on the left side of the panels indicate the position of the molecular weight markers.

Kinetics of p38 and JNK activation in eosinophils stimulated with eotaxin.

Eosinophils were stimulated and lysed as described for Figure 1. (A) Dual phosphorylation of p38 was detected by Western blotting with antibodies against threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (n = 3). (B) p38 was immunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts and tested in an immune-complex kinase assay using ATF-2 as the substrate. The activation of p38 was in agreement with the kinetics of dual phosphorylation. (C) JNK activation was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated JNK (α-PT/PY-JNK) (n = 3). Eotaxin failed to stimulate JNK activation above baseline.

Kinetics of p38 and JNK activation in eosinophils stimulated with eotaxin.

Eosinophils were stimulated and lysed as described for Figure 1. (A) Dual phosphorylation of p38 was detected by Western blotting with antibodies against threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (n = 3). (B) p38 was immunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts and tested in an immune-complex kinase assay using ATF-2 as the substrate. The activation of p38 was in agreement with the kinetics of dual phosphorylation. (C) JNK activation was assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated JNK (α-PT/PY-JNK) (n = 3). Eotaxin failed to stimulate JNK activation above baseline.

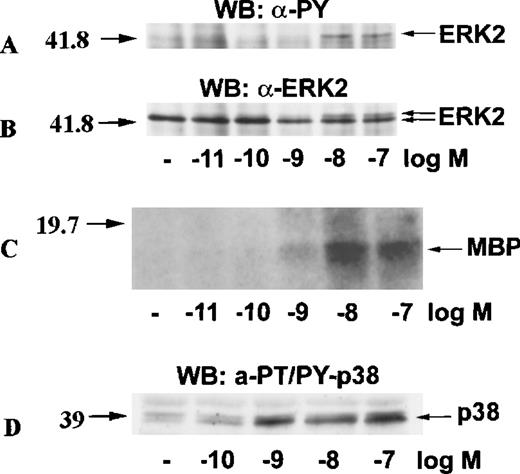

Eotaxin activates ERK2 and p38 in a concentration-dependent manner

To test whether the activation of ERK2 and p38 by eotaxin was concentration-dependent, we incubated eosinophils with medium or stimulated them with various concentrations of eotaxin for 1 minute. ERK2 was immunoprecipitated from cytosolic extracts. Western blotting with anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies followed by reprobing of the membrane with anti-ERK2 antibodies showed a concentration-dependent phosphorylation of ERK2 (Figure 3A and 3B). The result was verified by the immune-complex kinase assay (Figure 3C). Likewise, Western blotting of dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 revealed concentration-dependent activation (Figure 3D).

Concentration-response of ERK2 and p38 activation in eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils.

Eosinophils were stimulated with various concentrations of eotaxin for 1 minute. For panels A, B, and C, cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with the anti-ERK2 antibody. Tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK2 was detected by Western blotting with the anti-phosphotyrosine (anti-PY) antibody (A). Concomitant bandshifting was detected by reprobing the membrane with the anti-ERK2 antibody (B). This also verified that the tyrosine-phosphorylated band was ERK2 (n = 3). Further, the ERK2 immunoprecipitates were studied for kinase activity using MBP as the ERK2 substrate (C). For detection of p38 activation, cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (D). The activation of both ERK2 and p38 by eotaxin was concentration-dependent.

Concentration-response of ERK2 and p38 activation in eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils.

Eosinophils were stimulated with various concentrations of eotaxin for 1 minute. For panels A, B, and C, cytosolic extracts were immunoprecipitated with the anti-ERK2 antibody. Tyrosine phosphorylation of ERK2 was detected by Western blotting with the anti-phosphotyrosine (anti-PY) antibody (A). Concomitant bandshifting was detected by reprobing the membrane with the anti-ERK2 antibody (B). This also verified that the tyrosine-phosphorylated band was ERK2 (n = 3). Further, the ERK2 immunoprecipitates were studied for kinase activity using MBP as the ERK2 substrate (C). For detection of p38 activation, cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (D). The activation of both ERK2 and p38 by eotaxin was concentration-dependent.

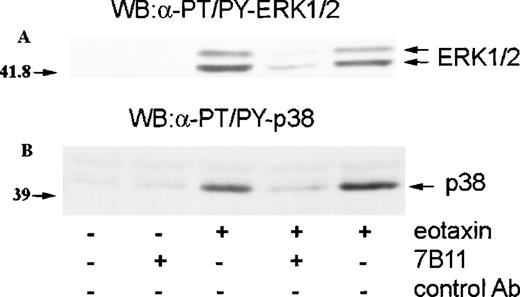

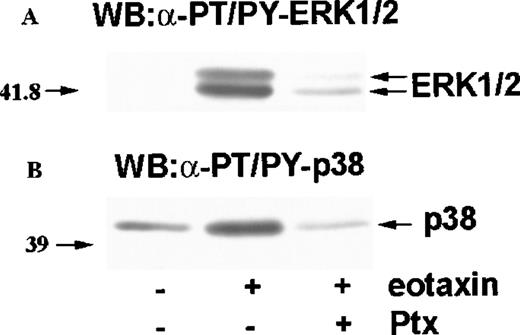

Activation of ERK2 and p38 by eotaxin is mediated through CCR3

Eotaxin is known to activate eosinophils through CCR3.11,12,14 To establish whether the activation of ERK2 and p38 by eotaxin was mediated through this receptor, we preincubated eosinophils with monoclonal anti-CCR3 blocking antibodies (7B11) or an isotype-specific control antibody. The cells were then incubated with medium or stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Western blotting with anti-dual–phosphorylated ERK1/ERK2 and p38 antibodies revealed that the anti-CCR3 blocking antibody caused a marked inhibition of ERK2 and p38 phosphorylation, indicating that the activation of the MAP kinases was mediated through CCR3 (Figure4). CCR3 is linked to pertussis toxin–sensitive heterotrimeric G proteins.11,12 14 To further confirm the receptor dependence of MAP kinase activation, we preincubated eosinophils with pertussis toxin (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour before stimulation with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. As assessed by Western blotting with antibodies against dual-phosphorylated ERK2 and p38, pertussis toxin inhibited the phosphorylation of both MAP kinases (Figure5), confirming that eotaxin exerts its effect through a receptor linked to a pertussis toxin–sensitive G protein.

Involvement of CCR3 in MAP kinase activation by eotaxin.

Eosinophils were preincubated with blocking monoclonal anti-CCR3 antibodies (7B11) or isotype-specific control antibodies for 30 minutes and stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated ERK2 (α-PT/PY-ERK1/2) (A) or dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (B). 7B11 blocked the phosphorylation of both ERK2 and p38.

Involvement of CCR3 in MAP kinase activation by eotaxin.

Eosinophils were preincubated with blocking monoclonal anti-CCR3 antibodies (7B11) or isotype-specific control antibodies for 30 minutes and stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated ERK2 (α-PT/PY-ERK1/2) (A) or dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (B). 7B11 blocked the phosphorylation of both ERK2 and p38.

Effect of pertussis toxin (Ptx) on MAP kinase activation by eotaxin.

Eosinophils were preincubated with buffer or Ptx (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour and stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Cytosolic extracts were used for Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated ERK2 (α-PT/PY-ERK1/2) (A) or dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (B). Ptx inhibited the phosphorylation of both ERK2 and p38.

Effect of pertussis toxin (Ptx) on MAP kinase activation by eotaxin.

Eosinophils were preincubated with buffer or Ptx (100 ng/mL) for 1 hour and stimulated with eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Cytosolic extracts were used for Western blotting with antibodies against dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated ERK2 (α-PT/PY-ERK1/2) (A) or dual threonine-tyrosine–phosphorylated p38 (α-PT/PY-p38) (B). Ptx inhibited the phosphorylation of both ERK2 and p38.

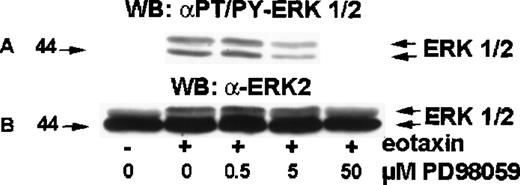

MEK inhibitor PD98 059 inhibits ERK2 activation by eotaxin

MEK (MAP ERK kinase) is a dual-specificity kinase that acts immediately upstream of ERK2 and catalyzes the simultaneous phosphorylation of tyrosine and threonine residues necessary to activate ERK2.18 PD98 059 is a selective MEK inhibitor.19-21 To test the involvement of MEK in eotaxin/CCR3–mediated activation of ERK2, eosinophils were preincubated with medium or 0.5, 5.0, or 50 μM of PD98 059 for 30 minutes at 37°C and stimulated with eotaxin (10−8mol/L) for 1 minute. The cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with the anti-phospho-ERK1/ERK2 antibody (Figure6A). The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with the anti-ERK1/ERK2 antibody (Figure 6B). PD98 059 induced concentration-dependent inhibition of ERK2 phosphorylation, which was detectable at 0.5 μM, clearly visible at 5 μM, and virtually complete at 50 μM.

Effect of MEK inhibitor PD98 059 on ERK2 activation in eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils.

Eosinophils were preincubated with medium or 0.5, 5.0, or 50 μM of PD98 059 for 30 minutes and stimulated with medium or eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with the anti-phospho-ERK1/ERK2 antibody (A). The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with the anti-ERK2 antibody (B). PD98 059 blocked ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (n = 4).

Effect of MEK inhibitor PD98 059 on ERK2 activation in eotaxin-stimulated eosinophils.

Eosinophils were preincubated with medium or 0.5, 5.0, or 50 μM of PD98 059 for 30 minutes and stimulated with medium or eotaxin (10−8 mol/L) for 1 minute. Cytosolic extracts underwent Western blotting with the anti-phospho-ERK1/ERK2 antibody (A). The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with the anti-ERK2 antibody (B). PD98 059 blocked ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner (n = 4).

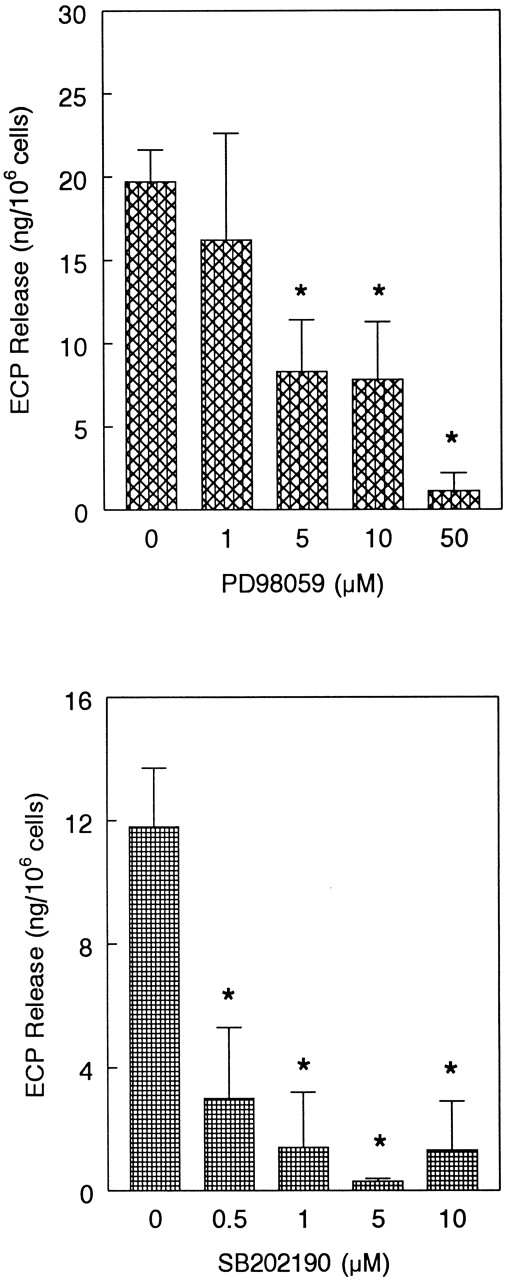

ERK2 and p38 play a role in eotaxin-induced ECP release and chemotaxis

Next, we tested the functional relevance of ERK2 and p38 in eosinophil release of ECP induced by eotaxin. We used the MEK inhibitor PD98 059 to inhibit ERK2 activation. Eosinophils were preincubated with the MEK inhibitor PD98 059 (0-50 μM) and the p38 inhibitor SB202 190 (0-10 μM) and stimulated with eotaxin (10−7 mol/L) for 4 hours prior to measurement of ECP in the supernatants. Both inhibitors caused concentration-dependent inhibition of ECP release (Figure 7). SB202 190 appears to have a greater inhibitory effect than PD98 059 on ECP secretion. The effect of the inhibitors was also studied on eosinophil chemotaxis in Boyden microchambers. Previous studies from other laboratories20 21 as well as our own experiment with ECP release suggested that 10- and 1-μM concentrations of PD98 059 and SB202 190, respectively, effectively inhibited MAP kinase-dependent biologic functions of various cells. For this reason, we used these concentrations of the inhibitors in the chemotaxis experiment. Cells were preincubated with the inhibitors and then applied in the upper chambers. The lower chambers contained eotaxin (10−8 mol/L). Both inhibitors significantly (P < .05) and nearly completely blocked eosinophil chemotaxis (Figure 8).

Effect of MEK inhibitor PD98 059 and p38 inhibitor SB202 190 on eotaxin-induced ECP release.

Eosinophils were preincubated with buffer, PD98 059 (1-50 μM), or SB202 190 (0.5-10 μM) for 1 hour and stimulated with eotaxin (10−7 mol/L) for 4 hours. ECP release was measured by radioimmunoassay. The number of eosinophil donors for PD98 059 and SB202 190 experiments were 4 and 3, respectively. The results are shown as the mean ± SD of ECP release from 106 cells. The values were corrected for the ECP release in buffer, which were 7.6 ± 3 and 6.9 ± 2.3 ng per 106 cells for PD98 059 and SB202 190 experiments, respectively. The inhibition of ECP release by 5, 10, and 50 μM of PD98 059 and by all tested concentrations of SB202 190 was statistically significant (*P < .05).

Effect of MEK inhibitor PD98 059 and p38 inhibitor SB202 190 on eotaxin-induced ECP release.

Eosinophils were preincubated with buffer, PD98 059 (1-50 μM), or SB202 190 (0.5-10 μM) for 1 hour and stimulated with eotaxin (10−7 mol/L) for 4 hours. ECP release was measured by radioimmunoassay. The number of eosinophil donors for PD98 059 and SB202 190 experiments were 4 and 3, respectively. The results are shown as the mean ± SD of ECP release from 106 cells. The values were corrected for the ECP release in buffer, which were 7.6 ± 3 and 6.9 ± 2.3 ng per 106 cells for PD98 059 and SB202 190 experiments, respectively. The inhibition of ECP release by 5, 10, and 50 μM of PD98 059 and by all tested concentrations of SB202 190 was statistically significant (*P < .05).

Effect of PD98 059 and SB202 190 on eotaxin-induced eosinophil chemotaxis.

Eosinophils from 4 donors were preincubated with buffer, PD98 059 (10 μM), or SB202 190 (1 μM) for 30 minutes and applied to Boyden chemotaxis microchambers. The lower chambers contained eotaxin (10−8 mol/L). Eosinophils were allowed to migrate through polycarbonate membranes for 1 hour. The migrated cells were counted and presented as the number of eosinophils per 5 fields. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The number of eosinophils migrated to buffer was below 20/5 fields. Both PD98 059 and SB202 190 inhibited eosinophil migration to eotaxin (*P < .05).

Effect of PD98 059 and SB202 190 on eotaxin-induced eosinophil chemotaxis.

Eosinophils from 4 donors were preincubated with buffer, PD98 059 (10 μM), or SB202 190 (1 μM) for 30 minutes and applied to Boyden chemotaxis microchambers. The lower chambers contained eotaxin (10−8 mol/L). Eosinophils were allowed to migrate through polycarbonate membranes for 1 hour. The migrated cells were counted and presented as the number of eosinophils per 5 fields. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The number of eosinophils migrated to buffer was below 20/5 fields. Both PD98 059 and SB202 190 inhibited eosinophil migration to eotaxin (*P < .05).

Discussion

Eotaxin and other CC chemokines acting via CCR3 are believed to play an integral role in the development of eosinophilic inflammation in asthma and allergic inflammatory diseases. In this study, we looked into the mechanisms of action of eotaxin and demonstrated that in eosinophils (1) eotaxin induced phosphorylation and activation of ERK2 and p38 but not JNK MAP kinases, (2) PD98 059 and SB202 190 inhibited eotaxin-induced ECP release, and (3) both inhibitors blocked eosinophil chemotaxis in response to eotaxin. We further confirmed that eotaxin activates eosinophils via CCR3 by a pertussis toxin–sensitive mechanism. These findings imply that both ERK2 and p38 are essential for eosinophil degranulation and locomotion.

Eotaxin was first discovered in guinea pig bronchoalveolar lavage fluid2 and, subsequently, both murine and human eotaxin has been cloned.22,23 Eotaxin is a potent chemoattractant for eosinophils and basophils and can further induce eosinophil degranulation and up-regulation of CD11b 10,13,22,24 (Figure 8). In vivo injection of eotaxin into the skin of mice25,26 and rhesus monkeys22 induces local accumulation of eosinophils, and the kinetics of allergen-induced production of eotaxin is paralleled by eosinophil accumulation in a guinea pig allergic airways model.27 Following allergen challenge, eotaxin-null mice display significantly diminished early accumulation of eosinophils into the lungs, whereas the late response appears normal.28 In patients with allergic asthma, increased levels of eotaxin are present in both bronchial biopsies and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid 4 hours after allergen inhalation. The increased levels of eotaxin are paralleled by increased influx of total and activated eosinophils and decreased forced expiratory volume in 1 second. This relationship disappears 24 hours after inhalation of the allergen.29Thus, eotaxin is likely to play an important role as a chemotactic and perhaps a mediator releasing factor, especially in the early phase of eosinophilic inflammation.

The MAP kinase family comprises at least 6 subsets: ERK1/ERK2, p38 kinases (p38, p38-β, -γ, and -δ), JNKs, ERK5, ERK6, and ERK7.30, 31-33 We found that activation of ERK2 and p38 was induced by nanomolar concentrations of eotaxin consistent with the concentrations necessary to induce chemotaxis and mediator release in vitro.10,13 ERK1 and ERK2 are activated by MEK1 and MEK2. PD98 059 inhibits both MEK1 and MEK2, presumably by binding to the inactive forms of these enzymes.20 We found that the inhibitor blocks eosinophil chemotaxis and ECP release. In agreement with our data, ERK2 has been shown to be essential for release of lytic mediators from NK cells34,35 and to be involved in catecholamine release from bovine adrenal chromaffin cells.36 Further, ERK2 has been reported to be activated through FcεRI in mouse bone marrow–derived mast cells. In these cells, PD98 059 inhibited serotonin release significantly.37

The p38 inhibitor SB202 190 and the analogous compound SB203 580 are widely used to assess the physiologic roles of p38.38-40 In our experimental setting, SB202 190 potently inhibited chemotaxis and ECP release from eosinophils. This is the first report on the essential role of p38 MAP kinase in eosinophil locomotion and degranulation. In neutrophils, p38 has been shown to be involved in degranulation induced by formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA).41 This indicates that p38 could be of broader importance for degranulation processes.

PD98 059 and SB202 190 inhibit MEK1 and p38 selectively with regard to a wide variety of other kinases.20,42,43 It should be noted, though, that both PD98 059 and SB203 580 were recently reported to inhibit cyclooxygenase in activated platelets. In the same study, SB203 580 was shown to inhibit thromboxane synthase.44 However, because prostaglandin D2 is without effect on eosinophil degranulation45 and prostaglandin F2 inhibits eosinophil ECP release,46 it would appear unlikely that diminished production of the prostanoid products of cyclooxygenase is responsible for the effects of PD98 059 and SB202 190 in our system. Still, at present it cannot be ruled out that other (perhaps yet unidentified) targets of PD98 059 and SB202 190 account for (part of) the inhibitory effect on eosinophil degranulation demonstrated in this study. However, in this context, it is noteworthy that we did not rely solely on the pharmacologic inhibitors but also demonstrated that eotaxin induced the activation of ERK2 and p38.

MAP kinases are involved in events intimately linked with the degranulation and chemotactic processes. On the signaling level, ERK2 and p38 phosphorylate phospholipase A2 and thereby increase its activity.47-49 Phospholipase A2 is necessary for fMLP-induced eosinophil degranulation to proceed.50 Both degranulation and chemotaxis involve profound rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton.51-53 ERK2 activity has been shown to be necessary for the integrity of the cytoskeleton in PC12 cells54 and in Chinese hamster ovary cells.55One of the substrates of ERK2 is the actin-binding protein caldesmon.56 The p38 MAP kinase also appears to play a role in the regulation of the cytoskeleton. It phosphorylates MAP-kinase–activated protein kinase 2/3, which phosphorylates heat shock protein 27.57,58 The latter is capable of modulating actin polymerization.59 Interestingly, in pancreatic acinar cells, the p38 inhibitor SB203 580 has been shown to block the MAP-kinase–activated protein kinase 2→heat shock protein 27 pathway as well as the changes in F-actin content induced by the secretagogue cholecystokinin.60 Thus, although the exact pathways remain to be elucidated, there are several potential mechanisms by which ERK2 and p38 could regulate eosinophil degranulation and chemotaxis.

While this manuscript was under review, Boehme et al published a paper demonstrating the activation of ERK1/ERK2 by eotaxin in eosinophils.61 The authors showed that PD98 059 inhibited eosinophil chemotaxis in vitro. The results are in agreement with the findings presented in this paper. The authors also demonstrated that PD98 059 blocked eotaxin-induced eosinophil rolling in the postcapillary venules of rabbit mesentery in vivo. Further, PD98 059 prevented eotaxin-stimulated F-actin polymerization in eosinophils. The results suggest that ERK1/ERK2 play an important role in multiple events related to eosinophil locomotion and directed migration. The growth and function of eosinophils are regulated by a number of cytokines. One of the important eosinophil regulators is interleukin (IL)-5. We have previously reported that IL-5 activates MAP kinases in eosinophils.62 Using SB202 190 and PD98 059, we have recently demonstrated that p38 and ERK1/ERK2 MAP kinases play an essential role in IL5-stimulated eosinophil differentiation and ECP release (unpublished data, ). The inhibitors also block eosinophil cytokine production. Thus, MAP kinases appear to represent a final common signaling pathway for IL-5 and eotaxin and critically regulate a number of important eosinophil functions.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI35137), John Sealy Memorial Foundation, the University of Texas Medical Branch, and Fonden til Allergiforskning paa Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. G.T.K. was supported by a travel grant from Fhv. Direktør Leo Nielsen og Hustru Karen Margrethe Nielsens Legat for Lægevidenskabelig Grundforskning.

Reprints:Rafeul Alam, Division of Allergy and Immunology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555-0762; e-mail: Ralam@utmb.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.