Abstract

The t(5;17) variant of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) fuses the genes for nucleophosmin (NPM) and the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RAR). Two NPM-RAR molecules are expressed as a result of alternative RNA splicing. Both contain RAR sequences that encode the DNA binding, heterodimerization, and ligand activation domains of RAR. This study was designed to test the ability of these fusion proteins to act as transcriptional activators of retinoic acid responsive promoters. The NPM-RAR fusion proteins bind to retinoic acid response element sequences as either homodimers or as heterodimers with RXR. Transcription of retinoic acid–inducible promoters is activated by the fusion proteins in the presence of retinoic acid. The level of transactivation induced by the NPM-RAR fusions differs from the level of transactivation induced by wild-type RAR in both a promoter and cell specific fashion, and more closely parallels the pattern of activation of the PML-RAR fusion than wild-type RAR. In addition, NPM-RAR decreases basal transcription from some promoters and acts in a dominant-negative fashion when co-transfected with wild-type RAR. Both NPM-RAR and PML-RAR interact with the co-repressor protein SMRTe in a manner that is less sensitive than RAR to dissociation by retinoic acid. Retinoic acid induces binding of the co-activator protein RAC3. These data indicate that the NPM-RAR fusion proteins can modulate expression of retinoid-responsive genes in a positive or negative manner, depending on context of the promoter, and lend support to the hypothesis that aberrant transcriptional activation underlies the APL phenotype.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL, FAB M3) is characterized by a rearrangement of 1 allele of the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα).1,2 RARα is a member of a class of nuclear receptor proteins that activate transcription of retinoic acid responsive genes. Like other members of the steroid receptor superfamily, the secondary structure of RARα is organized into modular functional units3: an A/B domain with transcriptional activating functions, a DNA binding C domain containing 2 zinc fingers, a D hinge, and a complex E/F domain that mediates ligand binding, dimerization, and interaction with co-repressor and co-activator transcriptional proteins. RARs preferentially form heterodimers with members of the RXR family of nuclear receptors.4,5 As heterodimers, RARs bind to well-defined DNA sequences (called retinoic acid response elements, or RAREs)6 and, on binding ligand, initiate transcription from target promoters.

The t(15;17) reciprocal chromosomal translocation that is found in leukemic cells from over 95% of patients with APL introduces downstream elements of the RARα gene on chromosome 17 into the PML locus on chromosome 15.7 8 The resulting PML-RAR fusion protein contains the N-terminal ring finger and leucine zipper motifs of PML joined to the RARα B-F domains.

Strong evidence indicates that expression of the PML-RAR fusion protein produces the APL phenotype.9-12 However, there is much controversy over the molecular mechanism by which PML-RAR alters myeloid growth and differentiation. PML-RAR retains the RARα DNA binding motifs and can interact with RARE sequences in vitro. It activates transcription from RARE reporter constructs in a ligand-dependent fashion. However, PML-RAR activity differs from wild-type RARα in a promoter- and cell-specific fashion, and can inhibit wild-type RARα function in a dominant-negative fashion.7,13 For these reasons it has been proposed that PML-RAR might function as an aberrant transcriptional activator of retinoic acid–responsive genes.7,8,14 Related to its putative function as a modulator of expression of retinoic acid–responsive genes is the recent set of observations that indicates PML-RAR binds to RAREs and recruits a co-repressor complex containing the nuclear co-repressor N-CoR (or the homologous silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors SMRT), Sin3, and histone deacetylase (HDAC1).15-18 This has led to the current paradigm17 that, unlike wild-type RARα that binds the co-repressor only in the absence of retinoic acid, PML-RAR continues to bind the co-repressor complex even in the presence of physiologic levels of retinoic acid, and releases the co-repressor only at pharmacologic levels of retinoic acid.

Alternative hypotheses have also been put forward. PML-RAR contains the dimerization domains of wild-type RARα and has been shown to bind the RARα heterodimerization partner RXR. By competing for free RXR, PML-RAR might inhibit the function of the unrearranged RARα.19 PML-RAR might also promote leukemogenesis by disrupting the function of wild-type PML protein,20 which has been shown to have a tumor suppresser function.21

One approach toward reconciling these seemingly disparate hypotheses is to study the rare variants of APL that do not express the PML-RAR fusion protein. The first such variant to be characterized was the t(11;17) of which 6 cases have been described worldwide.22,23 Blasts with the t(11;17) genotype, though, differ phenotypically from t(15;17) blasts, and do not differentiate when exposed to all-trans retinoic acid. It has been proposed that this phenotypic difference could be explained by the finding that the PLZF-RAR fusion product of t(11;17) is a less potent transcriptional activator than PML-RAR.24,25 This concept is further supported by recent studies indicating that PLZF-RAR forms more stable interactions with co-repressor molecules.18

Our group has characterized the t(5;17) variant, of which 3 cases have been identified.26,27 The t(5;17) blasts are morphologically similar to t(15;17) cells. Furthermore, like t(15;17), t(5;17) leukemic cells differentiate in vitro when cultured with all-trans retinoic acid.28 These phenotypic similarities make t(5;17) an important model system in which to identify common molecular pathways that underlie APL.

The t(5;17) chromosomal rearrangement translocates the genomic loci for the nucleolar phosphoprotein nucleophosmin (NPM) and RARα.27 Two NPM-RAR fusion proteins are expressed as a result of alternative splicing. NPMS-RAR contains 119 N-terminal amino acids of NPM; NPML-RAR contains an additional 43 amino acids immediately upstream to the junction with RARα sequence. Both forms of NPM-RAR fuse NPM sequence to the B-F domains of RARα that encode DNA binding, ligand binding, heterodimer formation, and transcriptional activation. This is the same region of RARα that is contained in the PML-RAR and PLZF-RAR fusions.

We characterize the ability of the NPM-RAR proteins to act as ligand-dependent transcriptional activators. We demonstrate that NPM-RAR-mediated transcriptional activation differs from wild-type RARα in a fashion that is both promoter and cell-type dependent. Both NPM-RAR fusion proteins interact with RAREs either as homodimers or heterodimers with RXR. Furthermore, both fusion proteins bind corepressor and coactivator proteins with retinoic acid dependence similar to PML-RAR. These results support the hypothesis that aberrant transcriptional activation of retinoic acid responsive genes contributes to the APL phenotype.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection protocols

CV1.

CV1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Bethesda, MD), and maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with glutamine, pen/strep, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY). Sixteen hours prior to transfection, 2 × 105 cells were replated in 6-well dishes with media containing delipidated FBS (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, PA). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine (GIBCO) and OptiMem serum-free media (GIBCO) according to the manufacturer's protocol; after 5 hours of incubation with the lipofectamine-DNA complexes, the media was readjusted to 10% delipidated FBS containing 1 μM all-trans retinoic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or an equal volume of ethanol vehicle. Transfection mixes contained 625 ng of chloramphenical acetyl transferase (CAT)-reporter plasmid, 125 ng of test transcriptional activator, pBluescript II KS as carrier, and 100 ng of RSV-luciferase as a transfection control.

HeLa.

HeLa cells were obtained from the ATCC. The cells were grown under the same conditions as CV1 cells. Sixteen hours before transfection, cells were plated in delipidated medium. Cells were transfected by coprecipitation of CaPO4-DNA complexes.29 Six hours after application of the DNA precipitates, the cells were washed and fresh delipidated medium containing 1 μM retinoic acid or ethanol vehicle was added.

K562.

K562 cells were obtained from the ATCC. Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech) supplemented with glutamine, pen/strep, and 10% FBS. Sixteen hours prior to transfection cells were washed and plated in RPMI containing 10% delipidated FBS. K562 cells were electroporated using a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 270 mV and 960 μF. 107 cells were transfected with a total of 20 μg of CAT reporter plasmid, transcriptional activator expression vector, RSV-luciferase, and carrier DNA in the same molar ratios as for the CV1 and HeLa transfections. Ater transfection the cells were incubated on ice for 15 minutes and plated in delipidated medium containing 1 μM retinoic acid or ethanol vehicle.

U937.

U937 cells were obtained from the ATCC. Culture and electroporation conditions were the same as for K562 cells.

Luciferase and CAT assays

Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were washed and lysed in 100 mM KHPO4 buffer, pH 7.8. Luciferase activity was determined by standard protocol29 using an AutoLumat LB 953 (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD). CAT activity was quantitated by scintography of xylene extracted C14-chloramphenicol-butyrate reaction product, using standard protocols.29

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

NPMS-RAR, NPML-RAR, and mRXRβ complementary DNAs (cDNAs), cloned into either pBluescript II KS or pSG5, were used to program reticulocyte lysates (TNT Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System, Promega, Madison, WI). Expression of appropriately sized proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting using either a polyclonal rabbit antiserum that recognizes the C-terminus of RARα (gift from P. Chambon), or a monoclonal anti-RXRβ antibody (Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO). The amount used for each assay was adjusted to compensate for discrepancies in the efficiency of the in vitro translation reactions. The in vitro translation product was incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes with 10 fmol32P-labeled oligonucleotide in 20 mM Hepes pH 7.9 buffer containing 50 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mmol/L DTT, and 1 μg salmon sperm DNA (for some reactions 2 μg poly (dI:dC) was used instead of salmon sperm carrier). The reaction mix was loaded onto a 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and exposed to Biomax MR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). The sequence of the RARβ RARE oligonucleotide is AGCTTGGGTAGGGTTCACCGAAAGTTCACTCGA30,31; for the cold-competition experiments a control unrelated oligonucleotide GATCGAAGACTAATCATGTCTGGGCAGATC, corresponding to a sequence in the p21 promoter,32 was used. Labeling of oligonucleotide was performed by Klenow fill-in reaction in the presence of32P-dCTP (NEN, Boston, MA).

Coprecipitation

The coding sequence for NPMS-RAR was subcloned into a malE expression vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) in the appropriate reading frame to encode a maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion. MBP-NPMS-RAR or control MBP protein was affinity-purified from bacterial lysates using amylose resin. 30 μg malE-fusion protein and 20 μL of35S-methionine–programmed reticulocyte lysate were mixed for 4 hours at 4°C in 20 mmol/L Tris pH8, 110 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, and 0.5% NP-40, and then allowed to bind to amylose resin. After extensive washing, the resin was boiled and the eluted products subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The gels were dried and imaged by autoradiography.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Programmed reticulocyte lysate (10 μL) was mixed at 4°C in 20 mmol/L Hepes pH 7.9, 50 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.05% Triton X-100, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and then incubated with 1 μg antibody (either anti-RXRβ rabbit polyclonal [Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA] or anti-RARα rabbit polyclonal [Santa Cruz Biotechnology]) for an additional 16 hours. Complexes were precipitated with Protein A-sepharose (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), washed, boiled, and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gel was dried and imaged by autoradiography.

Far-Western analysis

Far-Western blot analysis was conducted as described.33Bacterially expressed GST-fusion proteins were purified using glutathione agarose beads and separated in SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 192 mM glycine, 0.01% SDS. The bound proteins were denatured in 6 mol/L guanidine hydrochloride (GnHCl), and renatured by stepwise dilution of GnHCl in hybridization buffer (25 mM Hepes pH 7.7, 25 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT). The filters were blocked overnight with 5% nonfat milk in the hybridization buffer followed by a rinse in 1% nonfat milk plus 0.05% NP-40. In vitro translated35S-methionine labeled proteins generated in reticulocyte lysate (Promega) were hybridized to the immobilized proteins overnight in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.7, 75 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 1% milk, 1 mM DTT. After hybridization, the membrane was washed 3 times with hybridization buffer and the bound probe was detected by autoradiography.

Results

NPM-RAR acts as a retinoic acid–dependent transcriptional activator

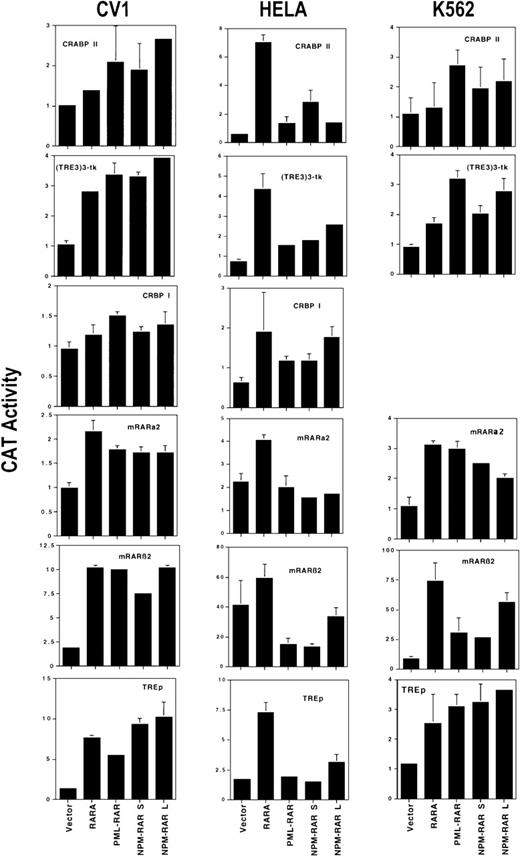

Preliminary observations indicated that NPMS-RAR and NPML-RAR are able to activate transcription of an mRARβ2-CAT reporter construct in a ligand-dependent fashion.27 We sought to determine whether such ligand-dependent transcriptional activation shows similar promoter and cell specificity as has been reported for PML-RAR.7,8,14 We compared the ability of NPMS-RAR, NPML-RAR, PML-RAR, and RARα to activate transcription of a series of retinoic acid–dependent reporter plasmids in CV1 monkey kidney cells, HeLa human cervical carcinoma cells, and K562 human myeloid leukemia cells. As reporter constructs 2 artificial RAREs (TREp-CAT34 and [TRE3]3-TK-CAT35), and 4 naturally occurring retinoic acid responsive promoters (mRARβ2-CAT containing 3.75 kb upstream to the mRARβ2 cap site,36,37 mRARα2-CAT containing 1.3 kb of promoter and 5′-untranslated sequence of mRARα2,38 CRABP-II CAT containing 2.5 kb of CRABP-II promoter,39 and CRBP-I CAT containing 2027 bases upstream to the transcriptional start site of CRBP-I36) were used. The graphs of Figure 1 present the ratio of CAT activity (normalized for transfection efficiency) from transfected cells incubated with retinoic acid compared with the ethanol control. CRBP-I CAT data are not presented in the analysis of K562 cells because the CAT activities were not significantly different from the no-lysate negative control.

Transcriptional activation. Expression vector pSG5 containing the coding sequence for RARα, PML-RAR, NPMS-RAR, or NPML-RAR was transfected into CV1, HeLa, or K562 cells along with CAT reporter genes driven by the CRABP II, (TRE3)3-tk, CRBP I, mRARα2, mRARβ2, or TREp promoter elements, and RSV-luciferase. Cells were incubated in 1 μM retinoic acid or ethanol vehicle for 16 hours after transfection and harvested for luciferase and CAT activity. The values indicate the ratio of the CAT activity induced with retinoic acid compared to ethanol, normalized for transfection efficiency. The mean and standard deviations for a minimum of 2 independent transfections are shown.

Transcriptional activation. Expression vector pSG5 containing the coding sequence for RARα, PML-RAR, NPMS-RAR, or NPML-RAR was transfected into CV1, HeLa, or K562 cells along with CAT reporter genes driven by the CRABP II, (TRE3)3-tk, CRBP I, mRARα2, mRARβ2, or TREp promoter elements, and RSV-luciferase. Cells were incubated in 1 μM retinoic acid or ethanol vehicle for 16 hours after transfection and harvested for luciferase and CAT activity. The values indicate the ratio of the CAT activity induced with retinoic acid compared to ethanol, normalized for transfection efficiency. The mean and standard deviations for a minimum of 2 independent transfections are shown.

The level of ligand-dependent activation by wild-type RARα varied for each reporter, as previously described.40 The variation of the level of activation generated with the control vector between cell lines, particularly evident with the mRARβ-CAT and mRARα2-CAT reporters, most likely reflects the activity of endogenous RARs and RXRs.

For each cell line, NPMS-RAR and NPML-RAR were similar in the degree of activation of each reporter construct, with NPML-RAR inducing slightly higher levels of transcription. Compared with RARα, the NPM-RAR fusion proteins were more active in CV1 cells toward CRABPII, but less efficient toward the mRARα2 reporter. In HeLa cells, both NPM-RAR fusion proteins were less efficient transcriptional activators than wild-type RARα for all the test constructs. With the mRARβ2-CAT and mRARα2-CAT reporters, the level of retinoic acid–induced transcription was less than that generated with the control vector, suggesting that the NPM-RAR fusions might be acting as inhibitors of endogenous RARα activation of these reporters.

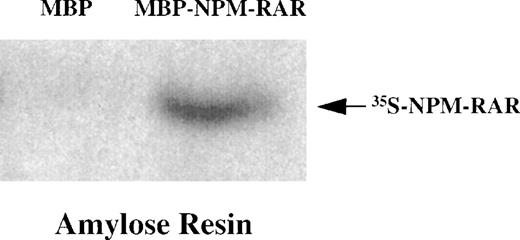

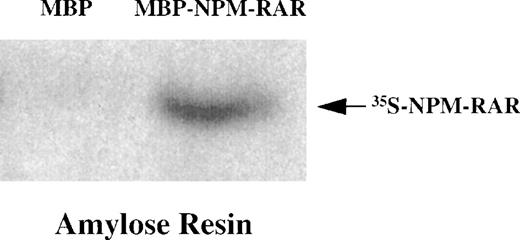

NPM-RARs form homodimers

In vitro interactions of the NPM-RARs with a target RARE were assessed in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Figure2 indicates that NPMS-RAR and NPML-RAR bind and retard the migration of a radiolabeled RARE. This was observed both with NPM-RAR proteins derived from in vitro translation (Figure 2A) or with affinity purified MBP-NPM-RAR protein (Figure 2C). The specificity of this reaction is documented by the competition reaction using cold RARE (Figure 2B and data not shown). The RARβ oligonucleotide contains a direct repeat of 2 consensus half-sites30 31; binding of NPM-RAR to this site led us to question whether the NPM-RAR fusion proteins might interact with DNA as a homodimer. To directly test the ability of NPM-RAR to homodimerize in solution, we incubated MBP-NPMS-RAR with in vitro translated 35S-NPMS-RAR protein, and captured the complexes using amylose resin (Figure 3). Recovery of the radiolabeled NPMS-RAR with MBP-NPMS-RAR, but not the MBP control, indicates that NPMS-RAR is able to form homodimers in solution.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (A) Two μL of NPMS-RAR charged reticulocyte lysate (left panel) or 5 μL NPML-RAR reticulocyte lysate (right panel) was incubated with 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, or 1.0 μl RXR reticulocyte lysate before incubation with radiolabeled RARβ oligonucleotide. (B) In vitro translated NPMS-RAR + RXR, NPML-RAR + RXR, or RXR alone were preincubated with 100-fold excess of cold control oligonucleotide (lane 1), cold RARβ oligonucleotide (lane 2), or no oligonucleotide (lane 3) before addition of the radiolabeled RARβ oligonucleotide. (C) 1 μg affinity purified MBP-NPMS-RAR was incubated with the radiolabeled RARβ oligonucleotide (lane 1) or preincubated with 100- (lane 2) or 1000-fold (lane 3) molar excess of unlabeled RARβ oligonucleotide before incubation with the labeled oligonucleotide.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay. (A) Two μL of NPMS-RAR charged reticulocyte lysate (left panel) or 5 μL NPML-RAR reticulocyte lysate (right panel) was incubated with 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, or 1.0 μl RXR reticulocyte lysate before incubation with radiolabeled RARβ oligonucleotide. (B) In vitro translated NPMS-RAR + RXR, NPML-RAR + RXR, or RXR alone were preincubated with 100-fold excess of cold control oligonucleotide (lane 1), cold RARβ oligonucleotide (lane 2), or no oligonucleotide (lane 3) before addition of the radiolabeled RARβ oligonucleotide. (C) 1 μg affinity purified MBP-NPMS-RAR was incubated with the radiolabeled RARβ oligonucleotide (lane 1) or preincubated with 100- (lane 2) or 1000-fold (lane 3) molar excess of unlabeled RARβ oligonucleotide before incubation with the labeled oligonucleotide.

NPMS-RAR forms homodimers. In vitro translated 35S-NPMS-RAR was incubated with MBP or MBP-NPMS-RAR protein. Complexes were purified over amylose resin and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE.

NPMS-RAR forms homodimers. In vitro translated 35S-NPMS-RAR was incubated with MBP or MBP-NPMS-RAR protein. Complexes were purified over amylose resin and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE.

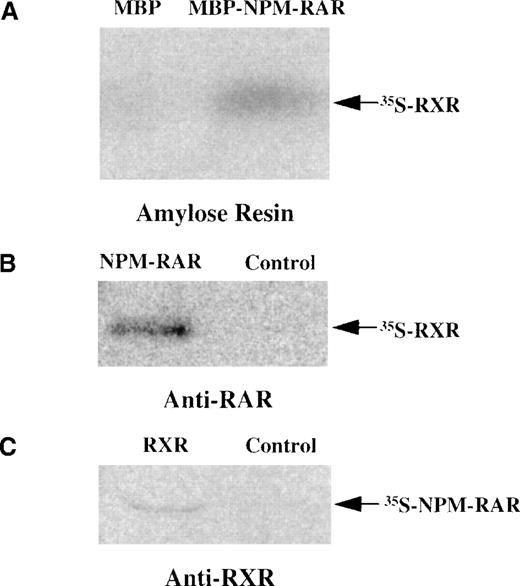

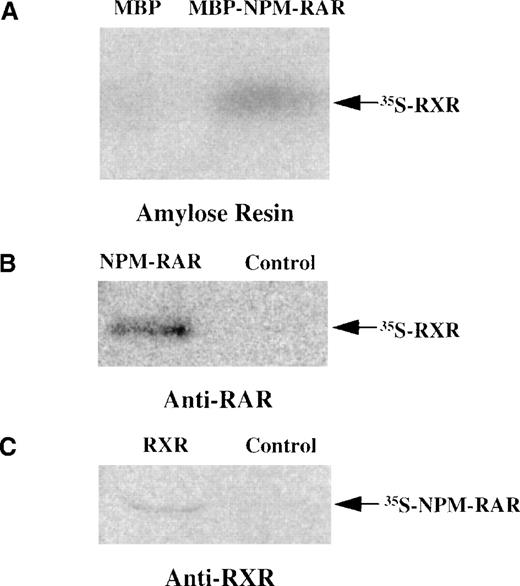

NPM-RAR can heterodimerize with RXR

Because the NPM-RAR fusion proteins contain the heterodimerization domains of RARα, it is reasonable to postulate that they might form heterodimers with RXR. To determine whether NPM-RAR can form heterodimers as well as homodimers, we incubated in vitro translated radiolabeled RXR with soluble MBP-NPMS-RAR, and captured the complexes with amylose resin. Figure 4A indicates that MBP-NPMS-RAR, but not control MBP protein, is able to form a stable complex with RXR. To confirm this data, we tested whether in vitro translated NPMS-RAR and RXR would associate in a complex that could be immunoprecipitated by antibodies to either constituent. Figures 4B and 4C indicate that NPMS-RAR and RXR proteins form a stable heterodimer complex that can be precipitated with either anti-RAR or anti-RXR antisera. Furthermore, co-transfection of RXR with NPMS-RAR or NPML-RAR increased ligand-inducible activation of an RARE-reporter construct (data not shown).

NPMS-RAR forms heterodimers with RXR. (A) In vitro translated 35S-RXR was incubated with MBP or MBP-NPMS-RAR protein. Complexes were purified over amylose resin and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. (B) 35S-RXR was preincubated with in vitro translated NPMS-RAR or control reticulocyte lysate before addition of anti-RAR antibody. Complexes were precipitated with Protein A-sepharose and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. (C) 35S-NPMS-RAR was preincubated with in vitro translated RXR or control reticulocyte lysate before addition of anti-RXR antibody. Complexes were precipitated with Protein A-sepharose and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE.

NPMS-RAR forms heterodimers with RXR. (A) In vitro translated 35S-RXR was incubated with MBP or MBP-NPMS-RAR protein. Complexes were purified over amylose resin and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. (B) 35S-RXR was preincubated with in vitro translated NPMS-RAR or control reticulocyte lysate before addition of anti-RAR antibody. Complexes were precipitated with Protein A-sepharose and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE. (C) 35S-NPMS-RAR was preincubated with in vitro translated RXR or control reticulocyte lysate before addition of anti-RXR antibody. Complexes were precipitated with Protein A-sepharose and analyzed on 8% SDS-PAGE.

If NPM-RAR can form homodimers or heterodimers, in which form does it preferentially interact with DNA? To address this issue, we preincubated the in vitro translated NPM-RAR with increasing amounts of RXR before performing an EMSA (Figure 2). We found that co-incubation of NPMS-RAR or NPML-RAR with less than equimolar amounts of RXR led to 5- to 10-fold increased binding of the RARE oligonucleotide, suggesting that the heterodimer-DNA complexes are more stable than the homodimer-DNA complexes. RXR alone did not induce a mobility shift of the RARE (Figure 2B). Intensity of the retarded complex decreased on preincubation with an excess of unlabeled RARE, indicating the specificity of this protein-DNA binding reaction (Figure2B).

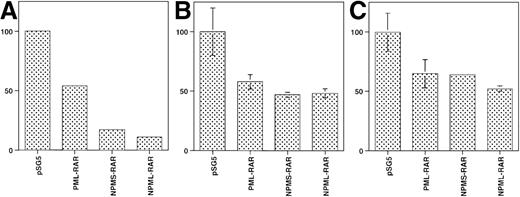

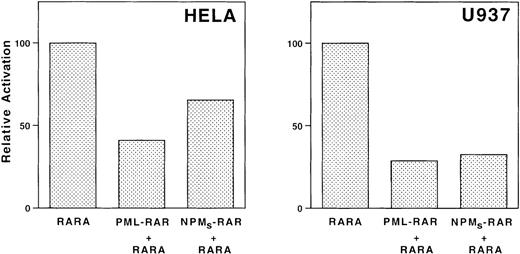

NPM-RAR acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of RAR

We observed that in the absence of retinoic acid, the basal transcription of several reporter constructs decreased on cotransfection of NPMS-RAR and NPML-RAR (Figure5). This suggested that the NPM-RAR proteins might act as dominant negatives for endogenous RARα, similar to what has been described for PML-RAR.7 13 To further investigate this possibility, we assessed the ability of co-transfected NPMS-RAR or PML-RAR to modulate RARα function. Both NPMS-RAR and PML-RAR suppressed the level of retinoic acid–induced activation of an RARE-reporter construct (Figure6). This indicates that like PML-RAR, NPMS-RAR can act as a dominant-negative inhibitor of RARα.

NPM-RAR decreases basal transcription of reporter constructs. Cells were transfected with pSG5, or expression plasmids encoding PML-RAR, NPMS-RAR or NPML-RAR along with a reporter construct and transfection control as in Figure1. Cells were harvested 16 hours after transfection, without addition of exogenous retinoic acid. The relative CAT enzyme activity for each experiment was normalized to the activity in cells transfected with pSG5. (A) TRE3-CAT in HeLa cells; (B) RARα2-CAT in K562 cells; (C) RARα2-CAT in HeLa cells.

NPM-RAR decreases basal transcription of reporter constructs. Cells were transfected with pSG5, or expression plasmids encoding PML-RAR, NPMS-RAR or NPML-RAR along with a reporter construct and transfection control as in Figure1. Cells were harvested 16 hours after transfection, without addition of exogenous retinoic acid. The relative CAT enzyme activity for each experiment was normalized to the activity in cells transfected with pSG5. (A) TRE3-CAT in HeLa cells; (B) RARα2-CAT in K562 cells; (C) RARα2-CAT in HeLa cells.

NPMS-RAR inhibits transcriptional activation by RAR. HeLa or U937 cells were transfected with mRARβ2-CAT and a luciferase transfection control along with equimolar amounts of pSG5 + RARα, PML-RAR + RARα, or NPMS-RAR + RARα. Cells were incubated in 1 μM retinoic acid or ethanol vehicle for 16 hours after transfection and harvested for luciferase and CAT activity. The values indicate the ratio of the CAT activity induced with retinoic acid compared to ethanol, normalized for transfection efficiency.

NPMS-RAR inhibits transcriptional activation by RAR. HeLa or U937 cells were transfected with mRARβ2-CAT and a luciferase transfection control along with equimolar amounts of pSG5 + RARα, PML-RAR + RARα, or NPMS-RAR + RARα. Cells were incubated in 1 μM retinoic acid or ethanol vehicle for 16 hours after transfection and harvested for luciferase and CAT activity. The values indicate the ratio of the CAT activity induced with retinoic acid compared to ethanol, normalized for transfection efficiency.

NPM-RAR interaction with nuclear receptor co-repressor and co-activator proteins

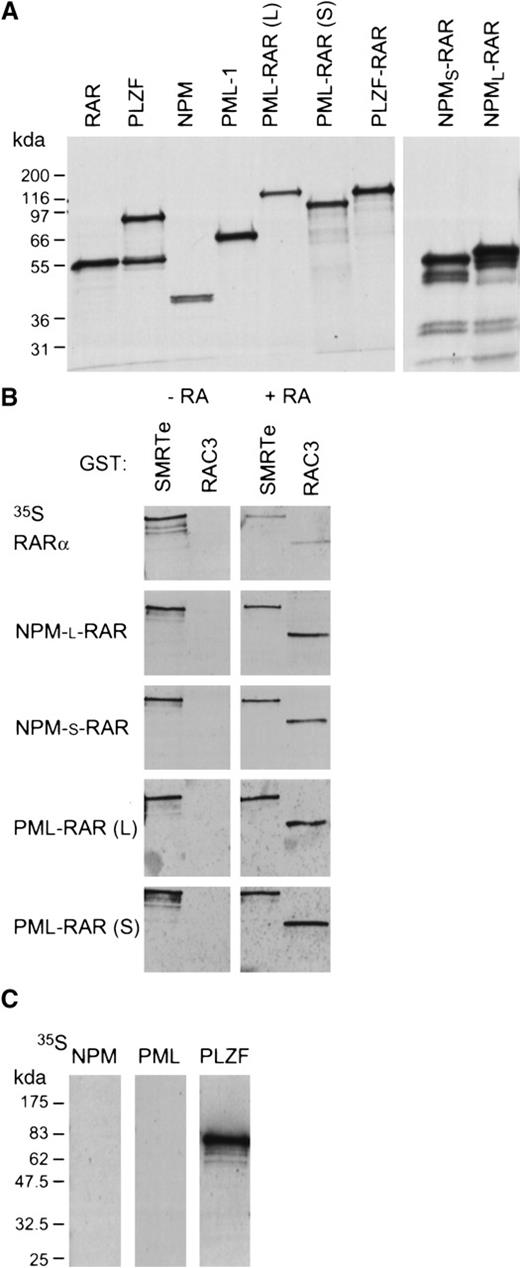

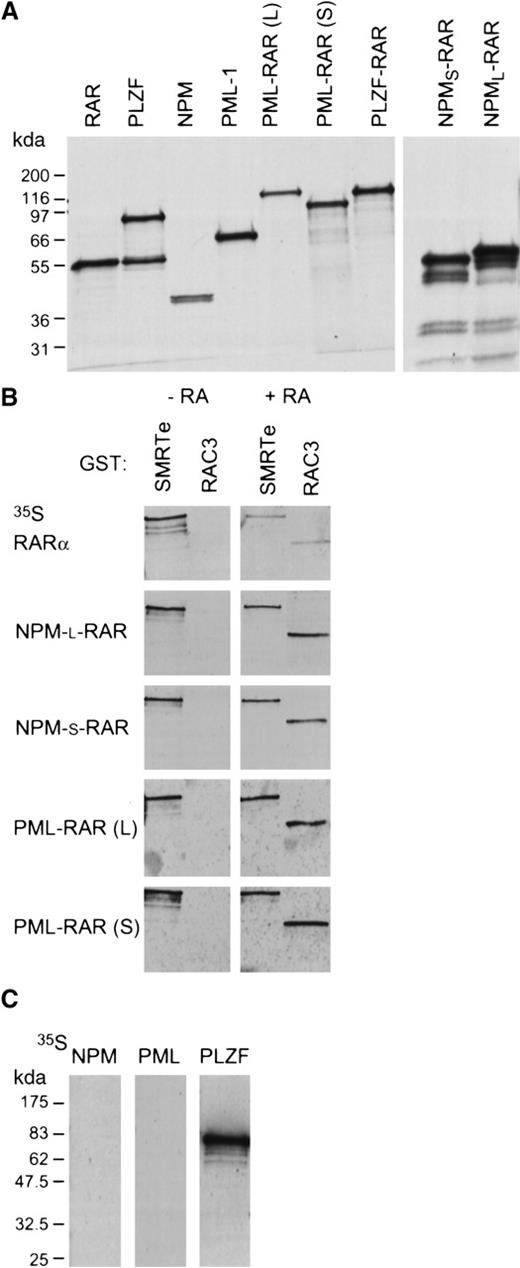

Transcriptional repression and activation by RARα is mediated through ligand-dependent recruitment of co-repressor or co-activator complexes (see review by Redner et al41). In the absence of retinoic acid, RARα binds directly to the co-repressor molecules SMRT or N-CoR. In the presence of retinoic acid, RARα releases the co-repressor complex and binds a receptor-associated co-activator protein (RAC33,42), which itself recruits other co-activator proteins.33 We used Far-Western analysis to assess the interactions of NPM-RAR with the co-repressor SMRTe43 and the co-activator RAC3.42 The specific activity of the probes were all similar and identical exposure times used. In the absence of ligand, wild-type RARα and both NPM-RAR and PML-RAR interact efficiently with C-SMRT (corresponding to AA 1993-2507 of hSMRTe), suggesting that the fusion proteins are not defective in co-repressor association (Figure7). As expected, unliganded RARα and the RAR fusion proteins fail to interact with the co-activator RAC3 in the absence of ligand.

NPM-RAR interacts with the co-repressor SMRTe and the co-activator RAC3. (A) Autoradiographs show the in vitro translated35S-methionine labeled proteins used in the Far-Western blots. (B) Far-Western blots show the interaction of in vitro translated RARα, NPM-RAR, and PML-RAR fusion proteins with GST-SMRTe (AA 1993-2507) and GST-RAC3 ID (AA 613-752) in the absence (−RA) or presence (+ RA) of 1 μM ATRA. The specific activity of all probes were similar and the exposure time identical in 1 film. (C) Far-Western blot analyses show the interaction of wild-type NPM, PML-1, and PLZF with GST-SMRTe (1993-2507).

NPM-RAR interacts with the co-repressor SMRTe and the co-activator RAC3. (A) Autoradiographs show the in vitro translated35S-methionine labeled proteins used in the Far-Western blots. (B) Far-Western blots show the interaction of in vitro translated RARα, NPM-RAR, and PML-RAR fusion proteins with GST-SMRTe (AA 1993-2507) and GST-RAC3 ID (AA 613-752) in the absence (−RA) or presence (+ RA) of 1 μM ATRA. The specific activity of all probes were similar and the exposure time identical in 1 film. (C) Far-Western blot analyses show the interaction of wild-type NPM, PML-1, and PLZF with GST-SMRTe (1993-2507).

Binding of retinoic acid to RARα efficiently dissociates SMRTe from the receptor and recruits the co-activator RAC3. We found that the association of SMRTe with the NPM-RAR fusion proteins is resistant to retinoic acid–induced dissociation (Figure 7B). Quantitation of the bound probes by PhosporImager analysis indicated that only 18% of the RARα probe that bound to the GST-SMRTe in the absence of ligand remained bound in the presence of ligand. Compared with the RARα probe, almost 3 times as much PML-RAR and twice as much NPM-RAR probe remained associated with GST-SMRTe in the presence of 1 μM retinoic acid. Interestingly, even though retinoic acid could not cause efficient release of the co-repressor, it is capable of inducing tight association with the co-activator RAC3 (Figure 7B). PhosphorImage analysis indicated that there was a 2- to 3-fold higher affinity between NPM-RAR or PML-RAR for the GST-RAC3 compared to wild-type RARα. In addition, we also tested whether wild-type NPM could interact with the co-repressor. We found no evidence of association between NPM and SMRTe under conditions that allow SMRTe to interact with PLZF (Figure 7C). These data suggest that NPM-RAR behaves similarly to PML-RAR in terms of protein–protein interactions with co-repressor and co-activator.

Discussion

We have previously identified 2 alternatively spliced forms of NPM-RAR that are expressed as a result of the t(5;17) translocation in APL.27 Both contain the DNA binding, dimerization, ligand binding, and C-terminal activation domains of RARα. We demonstrate here that both fusion proteins act as ligand-dependent transcriptional activators of a series of retinoic acid–responsive reporter constructs. We show that both forms of NPM-RAR interact with DNA as either homodimers or as RXR heterodimers. In addition, NPM-RAR interacts with co-activator and co-repressor proteins in a manner similar to PML-RAR.

The ability to form homodimer or heterodimer complexes has also been observed for PML-RAR14 and PLZF-RAR.44Heterodimer formation is mediated by the RARα E-domain coiled coil as well as a dimerization interface in the second zinc finger,45 and we presume that this region also mediates NPM-RAR/RXR heterodimerization. PML-RAR homodimer formation is primarily mediated through its PML-leucine zipper domain.14PLZF-RAR homodimer formation is mediated through the POZ domain.44 We have not as yet mapped the domains of NPM-RAR that mediate homodimer formation. However, N-terminal NPM domains contained within the NPM-RAR fusion have been implicated in wild-type NPM oligomerization46 and might be sufficient to mediate NPM-RAR homodimer formation. Alternatively, the coiled-coil of the RARα E-domain has been shown to mediate weak RARα homodimer formation,40 and might contribute to the stability of NPM-RAR homodimers. Whether the transcriptional activation that we observe is attributable to NPM-RAR homodimers or heterodimers is difficult to determine. The EMSA experiments presented in Figure 2indicate that less than equimolar amounts of RXR increase DNA binding of NPM-RAR 5- to 10-fold. This would indicate that the Ka for the heterodimer complex must be greater that the Ka for the homodimer complex, and suggests that NPM-RAR/RXR/RARE complexes would preferentially form over homodimer/RARE. All of the cell lines tested have endogenous RXRs, and it may be the case that the level of activation reflects heterodimerization with a limiting amount of endogenous RXR; CV1 cells, which have low levels of endogenous RXR, gave uniformly low levels of transcriptional activation (Figure 1), whereas increasing the level of RXR by transfection of exogenous mRXRβ augmented transcriptional activation (data not shown).

There is marked variation between the activity of NPM-RAR and wild-type RARα. This was seen with different promoters in the same cell line or for the same promoter in different cell lines. These differences may indicate alteration in DNA binding specificity caused by fusion of RARα to NPM, or modification in interactions with co-activator or co-repressor proteins (see below). Moreover, the level of induction of both NPM-RAR fusion proteins for each test plasmid more closely paralleled PML-RAR than RARα, with the only exception being the artificial construct TREp-CAT34 assayed in CV1 cells.

We found that both NPM-RAR fusion proteins have a dominant negative function over RARα. This conclusion is supported by both the suppression of basal transcription (Figure 5) and of RARα-mediated activation by NPM-RAR (Figure 6). Indeed, in HeLa cells, NPM-RAR acted as a transcriptional repressor toward the mRARα2- and mRARβ2-reporters (Figure 1).

Recently, several lines of evidence have indicated that the suppressive effects of PML-RAR and PLZF-RAR might be mediated through binding a co-repressor complex.15-18 Both PML-RAR and PLZF-RAR bind to retinoic acid response elements, and tether a co-repressor protein (SMRT or N-CoR) that recruits Sin3 and HDAC1. HDAC1 removes acetyl groups from nucleosomal histones in the neighborhood of the promoter, to allow the histones to bind more tightly to DNA, and to inhibit access of transcriptional machinery to the DNA template. Unlike wild-type RARα, PML-RAR and PLZF-RAR do not release the co-repressor complex on binding physiologic levels of retinoic acid, and so continue to repress transcription of genes that otherwise would be activated by physiologic doses of retinoic acid. Only at pharmacologic levels of retinoic acid does PML-RAR release the co-repressor complex. Because of a second co-repressor binding site in its POZ domain, PLZF-RAR does not release the co-repressor; this presumably explains the lack of retinoic acid responsiveness that characterizes PLZF-RAR APL.

We have found that wild-type NPM by itself does not bind SMRTe (Figure7C). Our observation that NPM-RAR binding to SMRTe is incompletely reversed by retinoic acid is consistent with previous studies on PML-RAR.17 Of note, the Far-Western blot (Figure 7B) indicates a residual interaction between RARα and GST-SMRTe in the presence of ligand; this has been seen as well in yeast 2 hybrid and mammalian 2 hybrid assays (J.D.C, unpublished data), and may indicate that a small proportion of receptors fail to bind ligand. Nevertheless, the interaction between NPM-RAR or PML-RAR with GST-SMRTe in the presence of retinoic acid was 2- and 3-fold greater than wild-type RARα. This finding suggests that NPM-RAR behaves similarly to PML-RAR in its reduced retinoic acid sensitivity in interaction with co-repressors,17 and is consistent with our prior observation that t(5;17) blasts are sensitive to the differentiating effects of high dose (1 μM) retinoic acid.28

The finding that NPM-RAR and PML-RAR are able to bind the co-activator RAC3 at concentration of retinoic acid at which the fusion proteins do not fully release SMRTe may indicate lack of uniformity of binding of ligand. Alternatively, this observation may suggest that the fusion proteins might bind both co-repressor and co-activator proteins simultaneously, and that there might be cross-talk between the co-repressor and co-activator in regulating transcriptional activity of the APL fusion proteins. Such a speculative model might account for the previously observed synergy between retinoic acid and HDAC1 inhibitors17,47 48; conceivably, retinoic acid could induce recruitment of a co-activator complex, whereas the HDAC inhibitor blocks the effects of the tethered co-repressor complex. The net result of the combination of histone acetylase and inhibited histone deacetylase activity would be hyperacetylation of promoter histones, leading to decreased affinity of the acetylated histones for DNA, and access of the transcriptional machinery to the DNA template. The interaction of APL fusion proteins with co-activator complexes has not been previously studied; it is as yet unclear whether RAC3 binds to NPM-RAR and PML-RAR through the RARα E-domain, or perhaps through a novel site. PhosphorImager analysis of the Far-Western blot suggests that the affinity of these fusion proteins for RAC3 may be greater than wild-type RARα.

The identification of a molecular pathway that is perturbed by both NPM-RAR and PML-RAR would implicate it as a key mechanism underlying APL. Recent mutational analyses of PML-RAR suggest that the transcriptional activation properties of PML-RAR are critical for its biologic function.25 49 Our observations strongly support the hypothesis that aberrant transcriptional activation or suppression of retinoid-inducible genes underlies APL. It remains to be determined which of the retinoic acid–responsive genes are critical to development of the APL phenotype.

Acknowledgments

pSG5-hRARα, mRARβ2-CAT, mRARα2-CAT, CRABP-II-CAT, CRBP-I-CAT, (TRE3)3-tk-CAT, and the rabbit anti-RARα antiserum were gifts from P. Chambon. TREp-CAT and PML-RAR cDNA were gifts from R. Evans, and mRXRβ cDNA was a gift from K. Ozato. We would also like to thank D. Johnson, D. Tweardy, and T. Wright for helpful discussions, and R. Steinman and S. Brandt for critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. R29 CA67346 (R.L.R.), the American Institute for Cancer Research Grant No. 96B057 (R.L.R.), and American Cancer Society Grant No. 98-085-01-LBC (J.D.C.).

Reprints:Robert L. Redner, E1058 Biomedical Science Tower, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, 211 Lothrop St, Pittsburgh, PA 15213; e-mail: redner+@pitt.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.