Sickling-induced cation fluxes contribute to cellular dehydration of sickle red blood cells (SS RBCs), which in turn potentiates sickling. This study examined the inhibition by dipyridamole of the sickling-induced fluxes of Na+, K+, and Ca++ in vitro. At 2% hematocrit, 10 μM dipyridamole inhibited 65% of the increase in net fluxes of Na+ and K+ produced by deoxygenation of SS RBCs. Sickle-induced Ca++ influx, assayed as 45Ca++uptake in quin-2–loaded SS RBCs, was also partially blocked by dipyridamole, with a dose response similar to that of Na+and K+ fluxes. In addition, dipyridamole inhibited the Ca++-activated K+ flux (via the Gardos pathway) in SS RBCs, measured as net K+ efflux in oxygenated cells exposed to ionophore A23187 in the presence of external Ca++, but this effect resulted from reduced anion conductance, rather than from a direct effect on the K+channel. The degree of inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes was dependent on hematocrit, and up to 30% of dipyridamole was bound to RBC membranes at 2% hematocrit. RBC membrane content of dipyridamole was measured fluorometrically and correlated with sickling-induced flux inhibition at various concentrations of drug. Membrane drug content in patients taking dipyridamole for other clinical indications was similar to that producing inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes in vitro. These data suggest that dipyridamole might inhibit sickling-induced fluxes of Na+, K+, and Ca++ in vivo and therefore have potential as a pharmacological agent to reduce SS RBC dehydration.

Introduction

Polymerization of sickle hemoglobin (HbS) upon deoxygenation produces dramatic changes in red cell shape,1 and the resultant membrane distortion is associated with an increase in permeability to Na+, K+, Ca++, and Mg++.2-6This sickling-induced change in permeability leads to cation loss and dehydration by 3 potential mechanisms: (1) imbalance between K+ loss and Na+ gain via the sickling-induced pathway per se in the presence of external Ca++,3,4 (2) unbalanced compensation by the Na+ pump (3 Naout for 2 Kin) in response to elevated cellular Na+,9 (3) increased Ca++ influx, with transient elevation of cellular Ca++ leading to activation of the Ca++-dependent K+ channel.4,8,10In turn, the resultant cellular dehydration potentiates sickling because of the high dependence of the rate of polymerization on HbS concentration,12 producing a vicious cycle of sickling → dehydration → sickling.

The physiological characteristics of the sickling-induced cation fluxes are most consistent with a passive diffusional pathway. These fluxes are linearly dependent on the concentration of the transported ion and are responsive to changes in membrane potential.2Sickling-induced fluxes of Na+ and K+ are independent of Cl− and do not require the presence of another transported ion on the cis or trans side of the membrane.2 These findings argue against known cotransport or countertransport mechanisms as mediators of the sickling-induced fluxes. Given equivalent electrochemical gradients, the fluxes of Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, and Cs+ are equal, and even the permeability of Ca++ through the pathway appears similar to that of Na+ when the 100-fold difference in concentration gradients across the membrane is considered.2,6,7 Curiously, however, organic cations, such as tetramethylammonium and tetraethylammonium which have ionic radii similar to monovalent alkali metal ions, appear to be relatively impermeant via the sickling-induced pathway by indirect measurement of their fluxes.2 These findings suggest that the sickling-induced cation fluxes are mediated by a cation channel, activated by sickling, which is nonselective among the alkali metal cations, but nevertheless discriminates between metal and organic ions. Because of the high basal anion permeability of the red blood cell (RBC) membrane, the selectivity of the sickling-induced pathway for cations over anions cannot be determined by flux measurements.13

Several inhibitors have been shown to block sickling-induced cation fluxes. DIDS (4,4′-di-isothiocyanato-2,2′-disulfostilbene) and related stilbene disulfonates inhibit the sickling-induced movements of Na+, K+, and Ca++.6,14We demonstrated that this inhibitory effect could be dissociated from inhibition of anion transport, indicating a site of action distinct from the normal anion exchange protein.14 Nifedipine and other Ca++ channel blockers inhibit sickling-induced dehydration of sickle (SS) RBCs,15 and we have found that sickling-induced Na+ and K+ fluxes were blocked by nifedipine.16 In addition, we found14,17that sickling-induced Na+ and K+ fluxes were inhibited by dipyridamole, a drug that blocks anion exchange18 but also exhibits broad pharmacological activity on nucleotide transport19 and other biochemical processes.20 Because of the therapeutic potential of dipyridamole for inhibiting sickling-induced cation fluxes and subsequent cellular dehydration in sickle cell patients, we undertook further study of dipyridamole inhibition of sickling-induced Na+, K+, and Ca++ fluxes and its relationship to drug binding to the RBC membrane. Preliminary reports of this work have appeared previously.16 17

Materials and methods

Blood samples

After informed consent, heparinized blood was obtained from normal controls and from individuals homozygous for HbS who had not been transfused within 3 months. Two additional patients with homozygous HbS and 2 with HbA who were taking dipyridamole and warfarin for previous thrombotic events donated blood for measurement of RBC membrane content of dipyridamole. Fluxes were not measured on samples from subjects taking dipyridamole, since measurement prior to drug therapy had not been made.

Hematocrits were measured on oxygenated samples in microhematocrit tubes, centrifuged 5 minutes at 13 000g. When stored overnight, cells were suspended in Hepes (N-2-hydroxyethyl-piperazine-N′-2-ethane sulfonic acid)–buffered solution containing 15 mM NaCl and 125 mM KCl. In some experiments, cells were fractionated according to density by centrifugation on discontinuous gradients of Percoll (Pharmacia, Upsala, Sweden), as described previously.3Whole blood was applied directly to gradients, which were centrifuged at 3000g in a Beckman GPR centrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) at 4°C. Cells were washed 3 times in Hepes-buffered saline (HBS) to remove gradient material, and the proportion of cells in the resultant fractions was calculated from hemoglobin measurements.

Incubation media and drugs

Unless otherwise noted, chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and were reagent grade or better. HBS contained 140 mM NaCl, 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4 at 37°C with NaOH), 0.1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM glucose. For Ca-influx measurements, buffer A contained 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), and 10 mM glucose; buffer B consisted of buffer A minus CaCl2 plus 0.1 mM ethyleneglycotetraacetic acid; buffer C was buffer A plus 2 mM adenine and 10 mM inosine. Dipyridamole was added as a stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which was present at a maximal concentration of 1% (vol/vol); DMSO had no effect on sickling-induced fluxes or basal cation permeability of RBCs. DIDS was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and added as a 10-mM stock solution in HBS, prepared fresh for each experiment.

Monovalent cation fluxes

Net Na+ and K+ fluxes were measured as described previously.2,3 14 Briefly, cells were washed and resuspended at 2% hematocrit in HBS containing ouabain (0.1 mM), and paired suspensions were subjected to oxygenated or deoxygenated conditions. An initial triplicate sample was taken at 15 minutes and a final sample at 135 minutes, and hemolysate cation concentration was measured by flame emission (PerkinElmer, Norwalk, CT, model 370 atomic absorption spectrophotometer). The hemoglobin concentration of each hemolysate, assayed optically at 540 nm on a Beckman Instruments DU spectrophotometer, was used to calculate cation content (millimole per kilogram of hemoglobin). Net fluxes were calculated as the change in cellular cation content with time; the difference between fluxes in deoxygenated and oxygenated cells constitutes the sickling-induced flux.

In one series of experiments, Rb+ influx was measured in cells incubated in HBS in which 5 mM RbCl replaced KCl. Cellular Rb+ content was measure by flame emission, as for Na+ and K+, on samples taken at 5 and 65 minutes. Rb+ influx was calculated as the change in Rb content over the incubation time, and the difference in Rb+ influx without and with 0.1 mM ouabain defined the Na+/K+ pump rate.

For measurement of KCl cotransport, cells were incubated for 1 hour at 37° at pH 6.8 in HBS or equivalent solutions in which NO replaced Cl−. Net K+efflux was calculated from the difference in cellular K+content at the beginning and end of the incubation. For swelling activation of KCl cotransport, cells were incubated in media containing 100 mM NaCl (NaNO3) at pH 7.4 (220 mOsm). In both conditions, the difference in K+ efflux in Cl− and NO media was taken to represent KCl cotransport activity.

Calcium influx

Ca++ influx was measured as45Ca++ uptake into cells loaded with quin-2 in a modification of the procedure of Rhoda et al.6 This approach allows the estimation of unidirectional influx rates for45Ca++ because efflux via Ca++-pump activity is inhibited, as accumulated intracellular Ca++ is chelated by quin-2 rather than being extruded by the pump.22 Cells of intermediate density (1.083 < δ < 1.094) were washed 3 times in buffer C and incubated 45 minutes at 37°C at 10% hematocrit to ensure repletion of cellular energy stores.22 After washing 3 times in buffer B, cells were incubated 1 hour at 37°C at 10% hematocrit with 40 μM quin-2 acetoxymethylester (Molecular Probes) added as a 10 mM-stock in DMSO. Cellular concentration of quin-2 under these conditions was estimated at 200 μmol per liter of cells by measurement of quin-2 fluorescence at 500 nm (excitation at 335 nm) on hemolysates of loaded cells.6

Quin-2–loaded cells were washed 3 times in buffer A and resuspended at 10% hematocrit. We transferred 2-mL aliquots to 20-mL glass tubes and added 0.1 M CaCl2 to give a final concentration of 1.0 mM. Dipyridamole was added as a 10-mM stock solution in DMSO to selected tubes, and DMSO was added to controls. Tubes were warmed to 37°C for 10 minutes in a heating block with constant stirring via magnetic fleas and fitted with stoppers with gas inlet ports. Deoxygenation was accomplished by flushing humidified N2through the tubes; oxygenated samples were capped. The hemoglobin concentrations of each suspension were unaffected by N2exposure, indicating adequate gas hydration. After 5 to 20 minutes of N2 exposure as indicated for individual experiments, 40 μCi 45CaCl2 (New England Nuclear, Boston, MA) was added, and single 100-μL samples were taken at 5-minute intervals for 45 minutes. Samples were taken into 1.5-mL Eppendorf tubes containing 1 mL of buffer A, layered over 200 μL dibutyl phthalate. Centrifugation at 13 000g for 1 minute pelleted the cells beneath the oil, and the tube was washed twice with buffer A without disturbing the cell pellet. After removal of the oil, the cells were lysed with 750 μL water. Hemolysates were precipitated with 250 μL of 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged, and aliquots of clear supernant were taken for counting. Samples of suspension were also precipitated with TCA and counted for measurement of 45Ca++-specific activity. Ca++uptake was calculated as micromoles per liter of cells and was plotted versus time; slopes of these lines yielded flux rates.

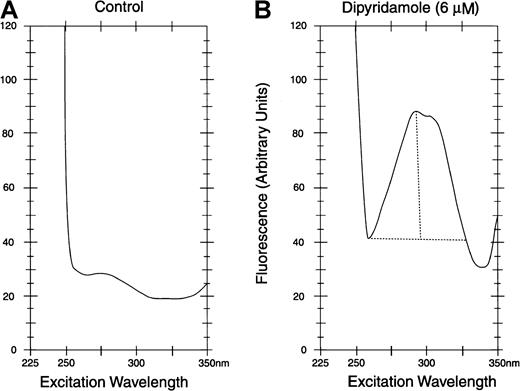

Measurement of dipyridamole in solution and RBC membranes

Dipyridamole was measured in HBS by fluorescence at 480 nm with excitation at 293 nm in a fluorescence spectrometer (Model Fluoro IV) (Gilford Instruments, Oberlin, OH). After exposure to dipyridamole in vitro or in vivo, cells were washed 3 times in HBS at 4°C and then lysed in 10 volumes of 5 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8 (5P8), and the ghosts washed until white. Suspensions of ghost protein were adjusted to 1.0 mg/mL, assay by the method of Lowry.23 Ghosts were diluted to 100 μg/mL in HBS and assayed by excitation scan by fluorescence spectroscopy, with emission monitoring at 480 nm, as shown in Figure1 for control ghosts (panel A) and ghosts exposed to dipyridamole (panel B). At the 293-nm excitation peak, the difference in the fluorescence reading between dipyridamole membranes and control membranes was measured. In all such assays, the same instrument settings were used consistently.

Fluorescence assay of dipyridamole in RBC membranes.

Excitation spectra with emission at 480 nm are shown. After exposure to dipyridamole, intact RBCs were washed before lysis and preparation of membranes (see text). Membrane protein concentration was 0.10 mg/mL in assay samples. For quantification of dipyridamole, the difference between peak fluorescence at 293 nm and minimum fluorescence at 265 nm was calculated (depicted in panel B).

Fluorescence assay of dipyridamole in RBC membranes.

Excitation spectra with emission at 480 nm are shown. After exposure to dipyridamole, intact RBCs were washed before lysis and preparation of membranes (see text). Membrane protein concentration was 0.10 mg/mL in assay samples. For quantification of dipyridamole, the difference between peak fluorescence at 293 nm and minimum fluorescence at 265 nm was calculated (depicted in panel B).

Results

Inhibition of sickling-induced Na+ and K+fluxes in SS RBCs by dipyridamole

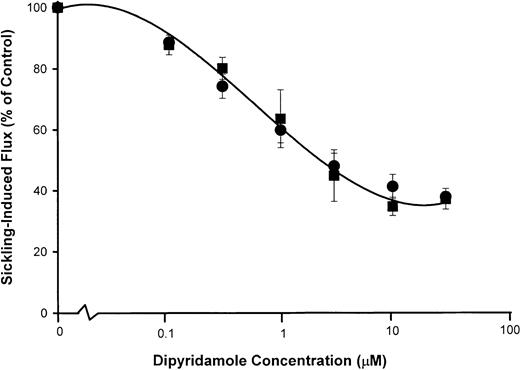

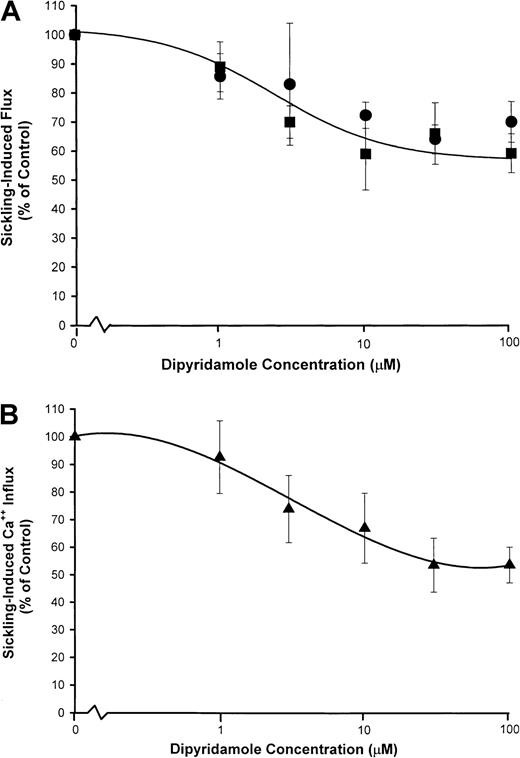

Figure 2 illustrates the effect of various concentrations of dipyridamole on sickling-induced Na+ and K+ fluxes measured at 2% hematocrit in HBS. It should be noted that the nominal drug concentrations in Figure2 do not correspond to “free” concentrations because of extensive binding of this lipophilic drug to RBCs, as is explored in detail below. Inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes was not a result of inhibition of sickling by dipyridamole. In a separate series of 3 experiments, control samples fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde exhibited 86% ± 3% sickle forms, and those exposed to dipyridamole showed 85% ± 2% sickling. There were no qualitative differences between control and drug-treated cells in the shape changes induced by deoxygenation (not shown).

Dipyridamole inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes of Na+ and K+.

Net fluxes were measured in 2-hour incubations at 2% hematocrit in the presence of the nominal concentrations of drug indicated. The sickling-induced flux was calculated as the difference in flux rates under oxygenated and deoxygenated conditions. Sickling-induced flux values in each experiment were normalized to the uninhibited control flux, which ranged from 14.7 to 35.1 mmol/kg Hb per hour in this set of 8 experiments from 6 individuals. Data points represent the mean (with SD) of these normalized values. ●, Na+ influx; ▪, K+ efflux.

Dipyridamole inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes of Na+ and K+.

Net fluxes were measured in 2-hour incubations at 2% hematocrit in the presence of the nominal concentrations of drug indicated. The sickling-induced flux was calculated as the difference in flux rates under oxygenated and deoxygenated conditions. Sickling-induced flux values in each experiment were normalized to the uninhibited control flux, which ranged from 14.7 to 35.1 mmol/kg Hb per hour in this set of 8 experiments from 6 individuals. Data points represent the mean (with SD) of these normalized values. ●, Na+ influx; ▪, K+ efflux.

The media in these experiments contained no external Ca++, so that K+ efflux from deoxygenated SS RBCs under these conditions was mediated predominantly by the sickling-induced pathway, with no measurable fluxes via the Ca++-activated K+ channel.3 However, because there is evidence that this channel is activated by Ca++ influx mediated by the sickling-induced pathway in vivo,10 we examined the effect of dipyrimadole on Ca++ fluxes in deoxygenated SS RBCs.

Inhibition of sickling-induced Ca++ influx by dipyridamole

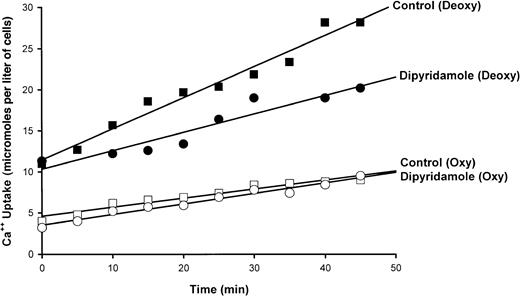

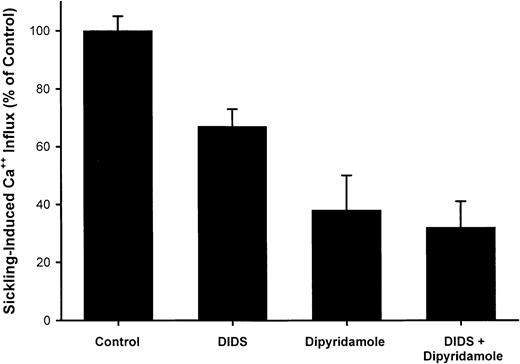

A typical experiment illustrating the effect of dipyridamole on45Ca++ influx in quin-2–loaded SS RBCs is shown in Figure 3. Ca++uptake in oxygenated cells was unaffected by drug; in 7 measurements, Ca++ influx was 0.24 ± 0.10 μmol per liter of cells per minute in control oxygenated cells and 0.23 ± 0.10 in oxygenated cells exposed to 100 μM dipyridamole. The increase in Ca++ uptake induced by deoxygenation is apparent in Figure 3 and is reduced in the presence of 100 μM dipyridamole. The results of 5 experiments of similar design are shown in Figure 4. Under these conditions, the sickling-induced Ca++ influx, calculated by subtracting the flux in oxygenated cells from that in deoxygenated cells, was inhibited 62% ± 12% by 100 μM dipyridamole. These data also illustrate that DIDS inhibited sickling-induced Ca++ influx by 33% ± 6%, confirming the findings of Rhoda et al.6 The combination of DIDS and dipyridamole did not produce significant additive inhibition, consistent with the 2 drugs acting on the same pathway.

Effect of dipyridamole on 45Ca++uptake in oxygenated and deoxygenated SS RBCs.

Cells were incubated at 10% hematocrit and exposed to humidified air or N2 as indicated. After 20 minutes,45Ca++ was added and samples were taken at indicated times. The slopes of the lines obtained by least squares analysis represent flux rates. A single experiment is depicted, representative of 10 such experiments.

Effect of dipyridamole on 45Ca++uptake in oxygenated and deoxygenated SS RBCs.

Cells were incubated at 10% hematocrit and exposed to humidified air or N2 as indicated. After 20 minutes,45Ca++ was added and samples were taken at indicated times. The slopes of the lines obtained by least squares analysis represent flux rates. A single experiment is depicted, representative of 10 such experiments.

Inhibition of sickling-induced45Ca++ uptake by dipyridamole and DIDS.

Ca++ influx rates were calculated as described in Figure3. The sickling-induced flux was calculated as the difference between the flux under oxygenated and deoxygenated conditions. DIDS concentration was 10 μM and dipyridamole concentration was 100 μM, at 10% hematocrit. Means and SDs of 5 experiments are shown.

Inhibition of sickling-induced45Ca++ uptake by dipyridamole and DIDS.

Ca++ influx rates were calculated as described in Figure3. The sickling-induced flux was calculated as the difference between the flux under oxygenated and deoxygenated conditions. DIDS concentration was 10 μM and dipyridamole concentration was 100 μM, at 10% hematocrit. Means and SDs of 5 experiments are shown.

Figure 5 shows the dose response to dipyridamole of sickling-induced Ca++ influx, compared with inhibition of sickling-induced Na+ influx and K+ efflux measured under the same experimental conditions as the 45Ca++ uptake measurements. Under these conditions, sickling-induced Ca++ influx was inhibited in parallel with Na+ influx, although the dose-response curve was somewhat different than in previous Na+ influx experiments (Figure 2). Differences in hematocrit (10% in Figure 5versus 2% in Figure 2) and different conditions of deoxygenation may account for this variation. Nevertheless, the similarity in the dose-response curve for inhibition of sickling-induced Ca++and Na+ influx, as illustrated in Figure 5, is consistent with mediation of the 2 fluxes by the same pathway.

dose response of dipyridamole inhibition of sickling-induced Na+ and Ca++ influx.

Washed cells were suspended at 10% hematocrit in the nominal dipyridamole concentrations indicated and then divided for separate measurements of Na+ (●) and K+ (▪) fluxes (A) and Ca++ influx (▴) (B). For both measurements, deoxygenation was carried out under similar conditions in parallel. Net Na+ and K+ fluxes were measured in the presence of 100 μM ouabain. Sickling-induced fluxes were calculated as described in Figure 2 and Figure 4. The fraction of the flux remaining relative to control samples without dipyridamole was calculated for each of 3 experiments.

dose response of dipyridamole inhibition of sickling-induced Na+ and Ca++ influx.

Washed cells were suspended at 10% hematocrit in the nominal dipyridamole concentrations indicated and then divided for separate measurements of Na+ (●) and K+ (▪) fluxes (A) and Ca++ influx (▴) (B). For both measurements, deoxygenation was carried out under similar conditions in parallel. Net Na+ and K+ fluxes were measured in the presence of 100 μM ouabain. Sickling-induced fluxes were calculated as described in Figure 2 and Figure 4. The fraction of the flux remaining relative to control samples without dipyridamole was calculated for each of 3 experiments.

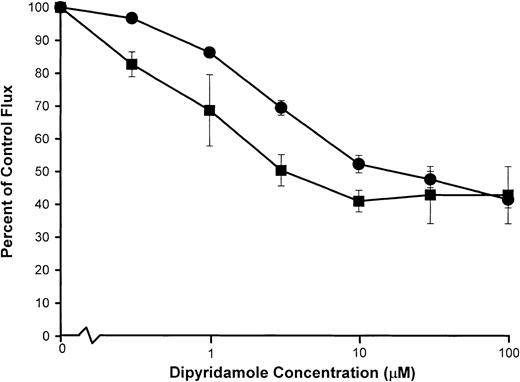

Inhibition of the Ca++-activated K+ channel (Gardos pathway) by dipyridamole

Under certain, but not all, experimental conditions, a portion of the K+ loss from deoxygenated SS RBCs appears to be mediated by transient activation of the Gardos pathway by Ca++ influx via the sickling-induced pathway.4,10,11 It is known that anion-transport inhibitors,23,25 including dipyridamole,18,21block Ca++-activated K+ fluxes since the extremely rapid, electrogenic K+ movements via the Ca++-activated channel are limited by conductive anion permeability, mediated predominately by the anion exchanger.26 We compared the dipyridamole dose response of the Ca++-activated K+ flux and the sickling-induced Na+ influx by parallel measurements of the 2 fluxes in aliquots of the same cell suspension under similar conditions of hematocrit and drug exposure as shown in Figure6. Ca++-activated K+ efflux was measured in SS RBCs incubated with ionophore A23187 in the presence of Ca++ at 2% hematocrit. Dose-dependent inhibition of the Ca++-dependent K+ efflux (Figure 6) occurred at higher concentrations of dipyridamole than are required for inhibition of the sickling-dependent Na+ influx measured under the same conditions.

Dipyridamole inhibition of Ca++-activated K+ fluxes compared with sickling-induced Na+influx.

Washed SS RBCs were suspended at 2% hematocrit and exposed to the nominal concentrations of dipyridamole indicated. Samples were then divided for separate measurement of sickling-induced Na+influx (▪) and (ionophore A23187) Ca++-activated K+ efflux (●) as described in “Materials and methods.” Flux values were normalized to the appropriate control flux (no drug). Mean values, with SDs, are shown for experiments in 3 individuals.

Dipyridamole inhibition of Ca++-activated K+ fluxes compared with sickling-induced Na+influx.

Washed SS RBCs were suspended at 2% hematocrit and exposed to the nominal concentrations of dipyridamole indicated. Samples were then divided for separate measurement of sickling-induced Na+influx (▪) and (ionophore A23187) Ca++-activated K+ efflux (●) as described in “Materials and methods.” Flux values were normalized to the appropriate control flux (no drug). Mean values, with SDs, are shown for experiments in 3 individuals.

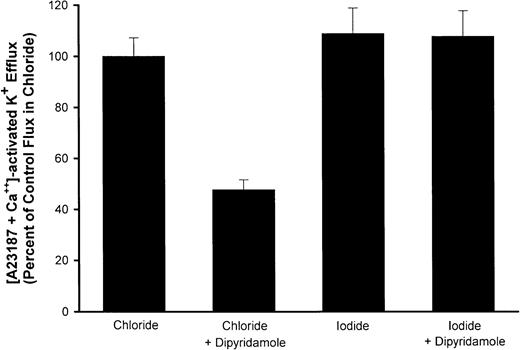

To demonstrate that dipyridamole inhibition of Ca++-activated K+ fluxes in RBCs under the conditions of these experiments was a consequence of the drug's action on anion permeability, we measured fluxes in media in which I− replaced Cl−. The conductive permeability of the RBC membrane to I− is not reduced by anion-exchange inhibitors.26 Therefore, if the effect of dipyridamole on Ca++-activated K+ fluxes is via blockade of anion movement, it should be lost with I− substitution. This was indeed the case experimentally, as is shown in Figure7. Thus, dipyridamole retards K+ efflux via the Gardos pathway, but by means of inhibition of conductive anion movements rather than a direct effect on the Ca++-activated K+ channel.

Effect of I− substitution for Cl− on dipyridamole inhibition of Ca++-activated K fluxes.

AA RBCs were washed with HBS or similar medium in which I−replaced Cl− and suspended at 2% hematocrit. Ca++-activated K+ efflux was measured as described in “Materials and methods” with or without 10 μM dipyridamole. Fluxes are normalized to the flux in Cl−media for each of 3 independent experiments, showing the mean and SD for each condition.

Effect of I− substitution for Cl− on dipyridamole inhibition of Ca++-activated K fluxes.

AA RBCs were washed with HBS or similar medium in which I−replaced Cl− and suspended at 2% hematocrit. Ca++-activated K+ efflux was measured as described in “Materials and methods” with or without 10 μM dipyridamole. Fluxes are normalized to the flux in Cl−media for each of 3 independent experiments, showing the mean and SD for each condition.

Electroneutral cation transport pathways or pathways mediating electrogenic cation movements, which are slow relative to K+ channel fluxes, are not rate-limited by conductive anion permeability and would not be expected to be affected by anion channel blockade. The sickling-induced pathway falls into the latter category. Indeed, we have demonstrated that inhibition by DIDS of the sickling-induced movements of Na+ and K+ is not abrogated by substitution of I− for Cl−.14 For this reason, we did not test the effect of dipyridamole on sickling-induced cation fluxes in the presence of I−. Nevertheless, because of the multiple pharmacologic activities of dipyridamole, we examined the effect of the drug on other monovalent cation transporters.

Effect of dipyridamole on the Na+/K+ pump and KCl cotransport

The effect of dipyridamole on the activity of the Na+/K+ pump was assessed by measuring ouabain-sensitive Rb+ uptake at 5 mM external Rb+ (see “Materials and methods”) in the presence or absence of 10 μM drug at 2% hematocrit. Pump activities were the same in control and drug-treated cells (5.5 ± 1.6 mmol/kg Hb per hour versus 5.2 ± 2.0 mmol/kg Hb per hour, respectively; n = 4 SS subjects). There was no effect of dipyridamole on ouabain-insensitive Rb+ influx rate. KCl cotransport, activated by either acidic or hypotonic conditions, was not consistently or significantly altered by dipyridamole. Cl−-dependent K+ efflux from SS RBCs incubated at pH 6.8 in isotonic solutions was 10.3 ± 3.9 mmol/kg Hb per hour in control cells versus 15.1 ± 3.0 mmol/kg Hb per hour in drug-treated cells (n = 3 SS subjects; P > .30 by paired t test). Swelling activated KCl cotransport, measured at normal pH in hypotonic solutions of 220 mOsm,27 was 7.2 ± 3.1 mmol/kg Hb per hour in control cells versus 5.1 ± 4.4 mmol/kg Hb per hour with drug (n = 4 SS subjects, P > .26).

Dipyridamole binding to RBCs

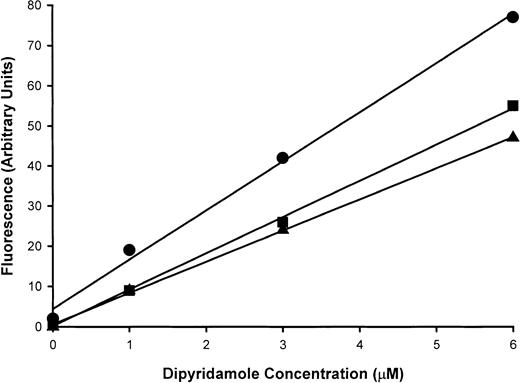

In pilot experiments, inhibition of sickling-induced Na+ influx at 10 μM dipyridamole was 64% ± 6% at 2% hematocrit, but only 43% ± 5% at 10% hematocrit.17This suggests that substantial dipyridamole binding to RBCs occurs in vitro; this was examined in 2 ways.

First, the removal of dipyridamole from media upon exposure to RBCs was investigated by measurement of residual dipyridamole in solutions by fluorescence, as described in “Materials and methods.” Figure8 illustrates the fluorescence values at several different drug concentrations. For the preparation of a standard curve (upper curve in Figure 8), cells were incubated without dipyridamole for 30 minutes at 2% hematocrit in HBS and then centrifuged. The supernatant was recovered and used to prepare solutions of various concentrations of dipyridamole for fluorescence assay, as depicted by circles in Figure 8. In parallel, the same concentrations of drug were added to identical 2% suspensions of RBCs, incubated, and then centrifuged; the fluorescence readings on these supernatants are shown in the middle curve (squares) of Figure 8. Fluorescence was reduced by 30% to 50% upon exposure to RBCs, depending on the initial concentration of drug. Because the control samples had been exposed to RBCs under similar conditions before the addition of drug, reduction in fluorescence by quenching by small amounts of extracellular hemoglobin can be eliminated as an explanation. To examine the role of hemoglobin in dipyridamole binding to intact RBCs, “red” ghosts containing 10% of normal hemoglobin concentration were prepared by osmotic lysis and resealing and were exposed to drug under similar conditions of hematocrit and drug concentrations (triangles in Figure 8). Supernatants were then recovered for fluorescence assay of dipyridamole. Ghost bound similar amounts of drug as intact RBCs. These results indicate that at 2% hematocrit, RBCs bind one third to one half of dipyridamole added in vitro and that the majority of the drug is bound by to the RBC membrane. This fact makes the interpretation of the dose response of dipyridamole inhibition of sickling-induced cation fluxes difficult, especially in comparison with pharmacological drug levels in patients taking the drug chronically, where tissue distributions of drug may be different from acute exposure of cells to drug in vitro. To address this issue, we compared the membrane content of dipyridamole required for inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes in vitro with membrane drug content achieved in vivo.

Dipyridamole binding to intact RBCs.

Dipyridamole fluorescence at 480 nm with excitation at 293 nm was assayed in supernatants of 2% RBC suspensions after the addition of the indicated concentrations of drug. The standard curve (●) was generated by means of supernatants obtained by centrifugation prior to exposure to drug, with subsequent addition of dipyridamole; this served as a control for possible quenching by small amounts of hemoglobin in the supernatant. Intact RBCs (▪) and red ghosts (▴) removed dipyridamole from the suspensions, as evidenced by reduced fluorescence in supernatants at all dipyridamole concentrations. A single experiment, representative of 2 others, is shown.

Dipyridamole binding to intact RBCs.

Dipyridamole fluorescence at 480 nm with excitation at 293 nm was assayed in supernatants of 2% RBC suspensions after the addition of the indicated concentrations of drug. The standard curve (●) was generated by means of supernatants obtained by centrifugation prior to exposure to drug, with subsequent addition of dipyridamole; this served as a control for possible quenching by small amounts of hemoglobin in the supernatant. Intact RBCs (▪) and red ghosts (▴) removed dipyridamole from the suspensions, as evidenced by reduced fluorescence in supernatants at all dipyridamole concentrations. A single experiment, representative of 2 others, is shown.

Measurement of dipyridamole content of RBC membranes and correlation with sickling-induced flux inhibition

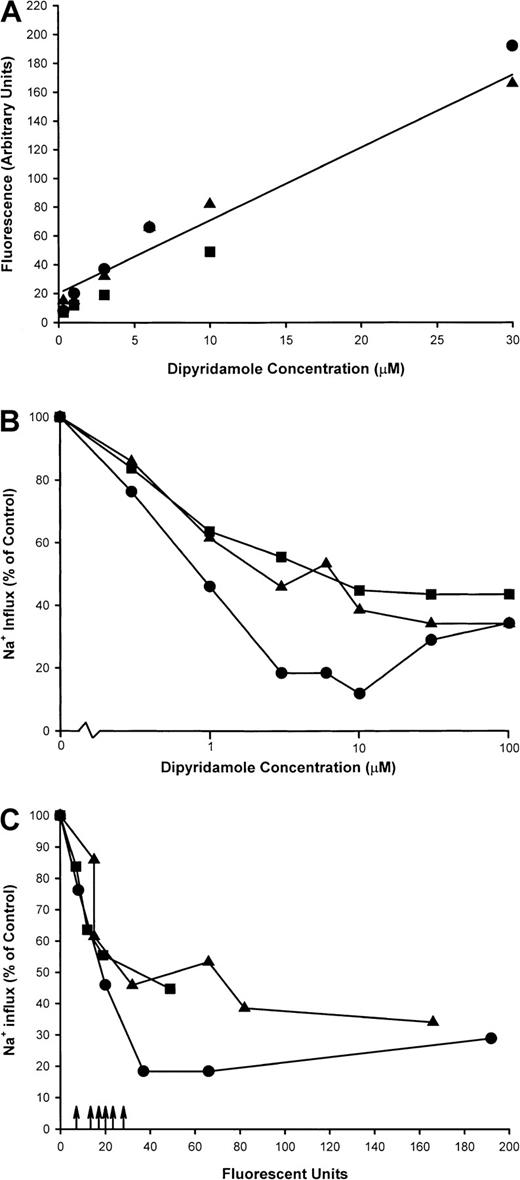

Sickle cells were incubated at 2% hematocrit in HBS at various concentrations of dipyridamole, and sickling-induced Na+influx was measured. From cells remaining after the flux measurement, ghost membranes were prepared as in Figure 1 for measurement of dipyridamole fluorescence. Figure 9A shows a linear relationship between membrane fluorescence and the nominal dipyridamole concentration in the incubation medium, indicating that drug binding to or partitioning into the membrane does not saturate in this concentration range. Inhibition of sickling-induced Na+ influx, however, saturates at around 30 μM nominal concentration, as illustrated in Figure 9B for these experiments. In Figure 9C, the sickling-induced Na+ influx values have been plotted against the membrane fluorescence values for each concentration of dipyridamole tested. This allows a comparison of the membrane content of dipyridamole required for inhibition of the sickling-induced flux to that achieved in patients taking the drug therapeutically. These values are depicted in Figure 9C as arrows on the x-axis for 2 patients with sickle cell anemia and 2 patients with Hb A. Although there is variation in the membrane levels of dipyridamole (including one SS patient in whom 2 determinations were made), it is apparent that the membrane content of drug achieved by oral administration of dipyridamole corresponds to that producing significant inhibition of sickling-induced fluxes in vitro.

Dipyridamole fluorescence in RBC ghost membranes.

Intact RBCs at 2% hematocrit were exposed to dipyridamole at the indicated nominal concentrations, and sickling-induced Na+influx was measured. Remaining cells were washed and ghosts prepared as described in “Materials and methods.” Fluorescence measurements were made at equal concentrations of membrane protein and identical fluorometer settings. Three experiments in different donors are shown as different symbols. (A) Fluorescence measurements (arbitrary units) in RBC ghosts as a function of nominal dipyridamole concentration in RBC incubation. (B) Sickling-induced Na+ influx as a function of nominal dipyridamole concentration. (C) Sickling-induced Na+ influx as a function of ghost fluorescence. Arrows represent fluorescence in ghosts derived from RBCs of patients taking dipyridamole.

Dipyridamole fluorescence in RBC ghost membranes.

Intact RBCs at 2% hematocrit were exposed to dipyridamole at the indicated nominal concentrations, and sickling-induced Na+influx was measured. Remaining cells were washed and ghosts prepared as described in “Materials and methods.” Fluorescence measurements were made at equal concentrations of membrane protein and identical fluorometer settings. Three experiments in different donors are shown as different symbols. (A) Fluorescence measurements (arbitrary units) in RBC ghosts as a function of nominal dipyridamole concentration in RBC incubation. (B) Sickling-induced Na+ influx as a function of nominal dipyridamole concentration. (C) Sickling-induced Na+ influx as a function of ghost fluorescence. Arrows represent fluorescence in ghosts derived from RBCs of patients taking dipyridamole.

Discussion

Dipyridamole has multiple pharmacological effects, which include inhibiting anion transport,18 blocking cellular adenosine uptake,19 inhibiting phosphodiesterase,20 and scavenging oxidant radicals.28 To that list of diverse effects on membrane processes, we now add blockade of the increased membrane permeability to Na+, K+, and Ca++ induced by sickling. Morphological sickling was not altered by the drug, so the inhibitory effect of dipyridamole does not result from interference with polymerization of deoxygenated HbS. Dipyridamole also blocks K+ efflux via the Ca++-activated K+ channel, because of its inhibition of anion movements.21 The persistence of Ca++-activated K+ fluxes in dipyridamole-treated cells incubated in I− media indicates that the drug has no effect on the K+ channel per se. Likewise, dipyridamole did not affect the Na+/K+ pump or the KCl cotransporter.

We and others have previously shown that another anion-transport inhibitor, DIDS, blocks the sickling-induced cation movements.6,14 However, several lines of evidence indicate that DIDS blockade of these cation movements is not a consequence of its inhibition of conductive anion permeability. First, DIDS inhibition of the anion exchanger could be dissociated from that of the sickling-induced pathway on the basis of differences in dose-response relationships and irreversible binding at 4°C. Second, several other anion-transport inhibitors (phloretin and sulfophenyl isothiocyanate) did not affect sickling-induced fluxes. Finally, substitution of I− for Cl− had no effect on DIDS inhibition of these cation fluxes.14 Thus, in contrast to Ca++-activated K+ movements, sickling-induced Na+ and K+ fluxes are independent of conductive anion permeability.

Although both the sickling-induced pathway and the Ca++-activated K+ channel are electrogenic,2 Na+ and K+ fluxes mediated by the sickling-induced pathway are not dependent on anion permeability for two reasons. First, under physiological conditions, Na+ influx and K+ efflux via the pathway nearly balance each other, so that little or no net anion flux is required to maintain electroneutrality. However, activation of a K+-selective channel produces a unidirectional cation [K+] efflux that requires equivalent anion movement. Second, the rate of the sickling-induced Na+ and K+ flux is several orders of magnitude lower than conductive anion movement, even in DIDS-treated cells.26Thus, even under conditions in which Na and K fluxes via the sickling-induced pathway were not balanced, conductive anion permeability would not be rate limiting. In contrast, opening of the Ca++-activated K+ channel produces a K+ permeability higher than Cl− permeability, so the anion movements that must accompany K+ efflux become rate-limiting, and drugs that reduce Cl−permeability therefore retard K+ fluxes via the channel.

Thus, it is unlikely that the capacity of dipyridamole to inhibit sickling-induced cation fluxes is related to the drug's effect on anion exchange. The differences in the dipyridamole dose-response curves of the sickling-induced cation flux and the Ca++-activated K+ flux (Figure 6) support this conclusion.

Partial inhibition of the sickling-induced fluxes by dipyridamole and DIDS could reflect the involvement of multiple pathways of variable sensitivity to inhibitors. However, the physiological characteristics of the sickling-induced fluxes suggest a single, passive diffusion pathway2 that does not distinguish between monovalent and divalent metal cations but does appear to exclude organic cations of similar size.2 We have suggested that the pathway reflects the activity of a nonselective cation channel, activated by the membrane distortion associated with sickling. Many of the characteristics of sickling-induced cation fluxes, including inhibition by DIDS,29 are shared by the passive cation leaks induced by high shear stress in normal and sickle RBCs.30Recently, we described single ion channels in membrane vesicles derived from the spectrin-depleted spicules of sickled RBCs. These ion channels were nonselective and were partially inhibited by DIDS as a result of reduction in open probability.31 Partial inhibition by DIDS and dipyridamole of sickling-induced cation fluxes in intact cells might result from similar effects on open probability of such a channel.

Dipyridamole inhibition of the sickling-induced cation transport pathway in vivo could have important implications for volume regulation of SS RBCs. Imbalance between Na+ influx and K+efflux via this pathway,3,4 magnified by the unbalanced stoichiometry of the Na/K pump,9 may produce gradual dehydration of SS RBCs in vivo. The sickling-induced pathway also mediates the influx of Ca++ responsible for transient activation of the Ca++-activated K+ channel, which can produce rapid dehydration.4,10 11 Even partial inhibition of sickling-induced Ca++-influx might prevent cellular ionized Ca++ from rising to the threshold of activation of the channel.

Dipyridamole inhibition of K+ efflux via the Ca++-activated channel might also retard dehydration of SS RBCs in vivo, even though the effect is secondary to reduction in net anion conductance. Bennekou32 has presented a detailed theoretical analysis demonstrating that anion-transport inhibition has the potential to retard rapid net cation loss in RBCs, especially that mediated by transient activation of high cation conductance pathways such the K+ channel. This phenomenon was demonstrated in vitro years ago by Eaton and colleagues,24 who showed that Ca++-activated K+ efflux was inhibited by DIDS. Gardos and colleagues showed that dipyridamole inhibited K+fluxes mediated by the Ca++-activated channel,21 although the mechanism of inhibition via anion channel blockade was not appreciated at that time. Recently, Bennekou and colleagues25 demonstrated blockade of Ca++-activated K+ efflux by a new anion-transport inhibitor, NS1652. This drug also inhibited K+ efflux in deoxygenated SS RBCs, although a direct effect of the drug on the sickling-induced pathway was not excluded. It should be re-emphasized that dipyridamole's inhibition of sickling-induced Na+, K+, and Ca++ fluxes is not a consequence of its effect on anion conductance, since these cation fluxes are not limited by anion movements. Nevertheless, the therapeutic potential of dipyridamole might be enhanced if Ca++-activated K+ channel activity was also inhibited in vivo by a pharmacologic reduction in anion conductance. In summary, dipyridamole might inhibit K loss from deoxygenated SS RBCs in vivo in 3 ways: (1) by inhibiting unbalanced Na+ and K+ movements mediated by the sickling-induced pathway; (2) by reducing sickling-induced Ca++ uptake to diminish activation of the Ca++-dependent K+ channel; or (3) by retarding K+ efflux (via reduction of anion conductance) through any K+ channels that were activated by residual sickling-induced Ca++ uptake.

Whether dipyridamole is capable of inhibiting SS RBC cation loss and dehydration in vivo will depend on several factors. First is the relative involvement of the inhibited pathways in the process of dehydration, compared with KCl cotransport, which is not affected. Brugnara and colleagues10 have shown that clotrimazole, an inhibitor of the Ca++-activated K+ channel, increases SS RBC cation content and reduces the number of dense cells in patients treated orally. This suggests that Ca++-activated K+ channel activation by sickling does indeed contribute to dehydration in vivo. A second factor that will affect the clinical efficacy of dipyridamole in sickle cell patients is the degree of inhibition of the sickling-induced pathways achievable in vivo by oral dosing. The present results suggest that membrane levels of drug sufficient for inhibition of these pathways are found in patients taking moderate therapeutic doses of dipyridamole.

Chaplin et al33 conducted a clinical study to determine if dipyridamole combined with aspirin would reduce the frequency and severity of vaso-occlusive episodes and mitigate the associated coagulation abnormalities. They treated 3 patients for several years in a nonblinded, longitudinal crossover study, accruing a total of 340 patient weeks on medication and 315 weeks off drug. Fibrinogen levels were not affected by treatment, although the increases in platelet count and high molecular weight fibrin complexes associated with pain episodes in control periods did not occur during treatment. During the study, there were no signs of toxicity or episodes of excessive bleeding. While on aspirin and dipyridamole, patients had approximately half the number of pain episodes and hospital days compared with control periods, findings remarkably similar to those of the multicenter trial of hydroxyurea in sickle cell disease.34 Hematological parameters were not measured, so no assessment of the effect of dipyridamole/aspirin treatment on RBC hydration state can be made. Although this study is small, it suggests that dipyridamole treatment is safe in sickle cell patients and might result in improvement in vaso-occlusive symptoms.

Several pilot studies have been based on reducing SS RBC dehydration by inhibition of various transport pathways. Brugnara and colleagues10 demonstrated that clotrimazole, an inhibitor of the Ca++-activated K+ channel, could block deoxygenation-induced dense cell formation in vitro. Oral administration of clotrimazole to sickle cell patients,35as well as to transgenic sickle cell mice,36 reduced the number of dense sickle cells in vivo. Following a suggestion first made by Bookchin et al,37 De Franceschi et al38,39 used oral Mg++ to increase cellular Mg++, thereby inhibiting the KCl cotransporter, thought to be an important mediator of cation loss in sickle reticulocytes.4,11 Mg++ supplementation reduced in vivo SS RBC dehydration in both mice and humans.38 39 In combination with other transport inhibitors, the inhibitory activity of dipyridamole against the sickling-induced transport pathway may prove useful in achieving inhibition of sickle cell dehydration in vivo with low levels of toxicity.

The authors wish to thank the many volunteers who donated blood samples to this study; Dr Donald Rucknagel and Annette Lavender, University Hospital of Cincinnati, for their assistance with obtaining these samples; and Mary Palascak and Ben Girdler for technical assistance.

Supported by US Public Health grants P60 HL58421 (C.H.J., R.S.F.), R01 HL57614 (C.H.J.), and R01 HL 51174 (R.S.F.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Clinton H. Joiner, Director, Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center, Children's Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039; e-mail: clint.joiner@chmcc.org.