Abstract

The contribution of specific type I collagen remodeling in angiogenesis was studied in vivo using a quantitative chick embryo assay that measures new blood vessel growth into well-defined fibrillar collagen implants. In response to a combination of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a strong angiogenic response was observed, coincident with invasion into the collagen implants of activated fibroblasts, monocytes, heterophils, and endothelial cells. The angiogenic effect was highly dependent on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, because new vessel growth was inhibited by both a synthetic MMP inhibitor, BB3103, and a natural MMP inhibitor, TIMP-1. Multiple MMPs were detected in the angiogenic tissue including MMP-2, MMP-13, MMP-16, and a recently cloned MMP-9–like gelatinase. Using this assay system, wild-type collagen was compared to a unique collagenase-resistant collagen (r/r), with regard to the ability of the respective collagen implants to support cell invasion and angiogenesis. It was found that collagenase-resistant collagen constitutes a defective substratum for angiogenesis. In implants made with r/r collagen there was a substantial reduction in the number of endothelial cells and newly formed vessels. The presence of the r/r collagen, however, did not reduce the entry into the implants of other cell types, that is, activated fibroblasts and leukocytes. These results indicate that fibrillar collagen cleavage at collagenase-specific sites is a rate-limiting event in growth factor–stimulated angiogenesis in vivo.

Introduction

Angiogenesis is the process by which the preexisting vascular tree gives rise to new blood vessels. This process is tightly regulated during development and occurs only under highly specialized circumstances in the normal adult animal. Unregulated angiogenesis may be a pivotal element of disease etiology, such as during tumor growth and atherosclerosis.1,2 All forms of angiogenesis, however, are thought to share certain basic features, including migration and mitogenesis of endothelial cells, lumen formation, connection of new vascular segments with the preexisting circulation, and extensive remodeling of the extracellular matrix by proteases. The detailed mechanisms by which proteolytic enzymes, such as the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), mediate some of these events in vivo remain unclear.3,4 The MMPs constitute a large family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases that have been strongly implicated in both normal angiogenesis and tumor vascularization.2,4 These enzymes are characteristically regulated at multiple levels, including gene expression, spatial localization, zymogen activation, and inhibition by the tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).5

In vitro remodeling of extracellular matrices by cultured endothelial cells has consistently been shown to rely on MMPs.4However, it is unclear which aspects of cell culture models for angiogenesis may be directly extrapolated to the animal. In vivo studies also have found evidence for a role of MMPs not only during tumor angiogenesis6-10 but also under the more controlled conditions of growth factor–induced angiogenesis. The MMP inhibitor, TIMP-1, can induce avascular zones in the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM)11 and can inhibit basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)-stimulated corneal neovascularization.12Both the synthetic MMP inhibitor BB-94 and TIMP-2 are able to block vascularization of fibrin gels in response to growth factors in vivo.13 Genetic experiments to address the roles of individual MMPs during angiogenesis in vivo suggest that certain MMPs are involved in the angiogenic process, depending on the biologic context.14-16 However, the detailed mechanisms by which angiogenesis is blocked through inhibition of MMP activity by chemical or genetic techniques have not been elucidated. It is also unclear which substrates are the relevant targets of these enzymes in vivo.

Type I collagen is the major constituent of the extracellular matrices to which proliferating endothelial cells are exposed in an injured tissue.17 Furthermore, endothelial cells in vitro proliferate preferentially on a substratum of interstitial collagen, compared to basement membrane collagen.18 Although collagen proteolysis has been characterized extensively under various biochemical conditions, the steps in collagen catabolism during angiogenesis in vivo have not been clearly delineated. Following recognition and cleavage between Gly775 and Ile/Leu776 by interstitial collagenase,19 the resultant three-quarter length and one-quarter length fragments of type I collagen exhibit decreased stability of the triple helix, permitting further degradation by the gelatinases.20 Wu and coworkers genetically engineered collagen I to be completely resistant to collagenase by substituting amino acids at and adjacent to the specific cleavage site21and subsequently produced transgenic mice expressing only the collagenase-resistant collagen α1(I).22 The ability of these mice to undergo postnatal angiogenesis has not been studied, although a collagen that is resistant to interstitial collagenase provides a unique tool to examine this issue.

The goal of the studies described herein was to establish a quantitative in vivo model of angiogenesis and then to use it to investigate not only the MMP-mediated collagenolytic activities in the model but also the role of the major substrates of these enzymes. The chick embryo CAM has been widely used for the study of angiogenesis because it provides a means of examining neovascularization in vivo while still allowing for a high level of control and ease of manipulation.23 Most CAM assays, however, rely on subjective scoring procedures and may not distinguish clearly between preexisting blood vessels and those that arise following an angiogenic stimulus.24 To circumvent these problems, Nguyen and colleagues developed a system for monitoring blood vessel growth that uses a fibrillar collagen implant and allows direct quantitation only of new blood vessels.25 After modifying this system for a more robust angiogenic response, we established the importance of MMP activity in the model by using both synthetic and natural MMP inhibitors. Experiments designed to alter the extracellular matrix substratum by using the collagenase-resistant, mutant collagen, revealed that the initial putative cleavage of interstitial collagen at the Gly775/Ile776 locus is required for the full angiogenic effect of growth factors. We propose that the mechanism of MMP inhibitor–mediated effects on angiogenesis is at least in part through inhibition of highly specific collagenolytic activity.

Material and methods

Chicken embryo culture

Fertilized COFAL-negative eggs (SPAFAS, Storrs, CT) were incubated at 38°C with 60% humidity for 3.5 days in an egg incubator (Humidaire, New Madison, OH). Shells were scored equatorially with a cut-off wheel (Dremel, Racine, WI) and manually opened over sterile plastic weigh boats (medium, 9 × 9 × 2.5 cm, VWR, San Diego, CA), and the intact embryos were carefully spilled into the weigh boats. Weigh boats were covered with bottoms of square 100 × 100 mm Petri dishes (no. 4021, Nunc, Rochester, NY). Embryos were then maintained in a humidified cell culture incubator at 37.5°C with 90% humidity.

CAMangiogenesis assay

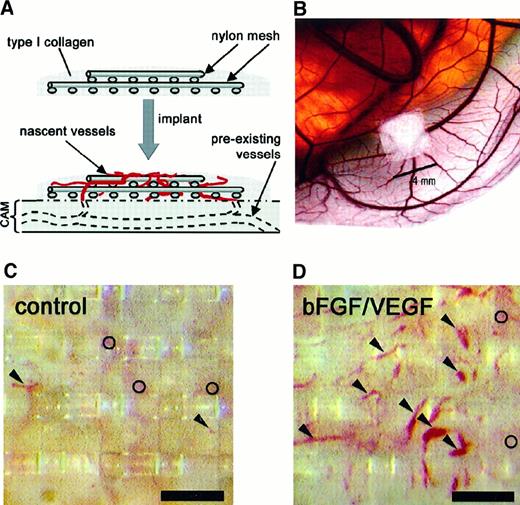

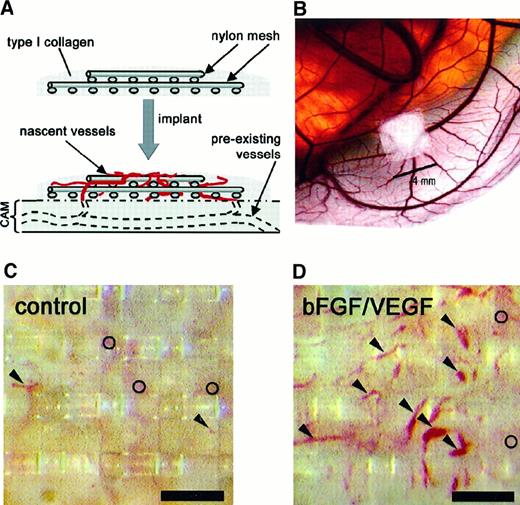

The angiogenic effect of growth factors (bFGF and/or vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF]) in the presence or absence of inhibitors was tested on the CAM using a technique described by Nguyen and colleagues25 (Figure1A,B). The following modifications were made to the original protocol: embryos were incubated in a dish that more closely reflects the true shape of the egg26; collagen implants were grafted onto CAMs on day 10 of incubation, instead of day 8 to 9; and a combination of growth factors, rather than bFGF alone, was presented to the embryo through the collagen implant.

Implants of fibrillar type I collagen support neovascularization and allow for in vivo quantitation of angiogenesis.

The angiogenesis assay relies on the upward invasion of newly forming blood vessels from the CAM into the collagen implant where they are microscopically scored. (A) Schematic illustrates type I collagen polymerized around 2 layers of nylon mesh to form a grid-embedded implant. The implant is then placed on the CAM, from which new blood vessels arise and grow up into the collagen and through the grids of the mesh. (B) Stereomicroscopic view of a collagen implant placed on the CAM of a 10-day chick embryo developing ex ovo. In the photomicrographs shown (C,D), the collagen in the implant had been copolymerized with buffer alone (C) or with bFGF/VEGF (D). The collagen implants were then incubated on the CAM for 65 hours. Blood vessels in representative implants were photographed in vivo through a stereomicroscope. New vessels that grow up into the implants are visualized within the grid boxes of the nylon mesh and scored as positive. Arrowheads indicate only some of these scored vessels. The preexisting, underlying CAM vessels are out of focus (○) and are never scored in the assay. The presence of bFGF and VEGF in the implants (D) clearly enhances the angiogenesis score over the control implants (C). Bar in panels C and D is 300 μm.

Implants of fibrillar type I collagen support neovascularization and allow for in vivo quantitation of angiogenesis.

The angiogenesis assay relies on the upward invasion of newly forming blood vessels from the CAM into the collagen implant where they are microscopically scored. (A) Schematic illustrates type I collagen polymerized around 2 layers of nylon mesh to form a grid-embedded implant. The implant is then placed on the CAM, from which new blood vessels arise and grow up into the collagen and through the grids of the mesh. (B) Stereomicroscopic view of a collagen implant placed on the CAM of a 10-day chick embryo developing ex ovo. In the photomicrographs shown (C,D), the collagen in the implant had been copolymerized with buffer alone (C) or with bFGF/VEGF (D). The collagen implants were then incubated on the CAM for 65 hours. Blood vessels in representative implants were photographed in vivo through a stereomicroscope. New vessels that grow up into the implants are visualized within the grid boxes of the nylon mesh and scored as positive. Arrowheads indicate only some of these scored vessels. The preexisting, underlying CAM vessels are out of focus (○) and are never scored in the assay. The presence of bFGF and VEGF in the implants (D) clearly enhances the angiogenesis score over the control implants (C). Bar in panels C and D is 300 μm.

Briefly, pure type I collagen (Vitrogen) at 3.1 to 3.3 mg/mL (8 parts) was neutralized with 10 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 1 part) and 0.1 N NaOH (1 part). For some experiments, pepsinized dermal collagens derived from wild-type (WT) or homozygous mutant collagenase–resistant (r/r) mice (a gift of Dr Stephen M. Krane)22 were substituted for Vitrogen. Hepes solution (1 M) was added to 20 mM final concentration to the neutralized collagen solutions to ensure stable pH 7.4. Two parts neutralized collagen solution were then combined with sterile PBS solutions (1 part) containing bovine serum albumin (BSA; final concentration, 1 mg/mL) as a carrier protein, with or without bFGF (Fiblast, final concentration 16.7 μg/mL), a gift from Dr Judith Abraham (Scios, Sunnyvale, CA) and VEGF (Peprotech; final concentration 5 μg/mL). For some experiments the soluble hydroxamate MMP inhibitor, BB3103 (British Biotech, Oxford, United Kingdom), was also incorporated into the collagen gels at 1.4 μg/implant (final concentration, 100 μM) with subsequent doses of 0.24 μg/implant added topically on days 11 and 12. Recombinant C–terminally truncated TIMP-1 (N-TIMP-1), a gift from Dr Steven R. Van Doren (University of Missouri, Columbia, MO),27 was incorporated at 1.8 μg/implant, with subsequent doses of 1.8 μg/implant given topically as above.

Thirty microliters of the final collagen/growth factor solution with or without experimental compounds was then pipetted atop 2 layers of sterile nylon mesh (lower layer, 4 × 4 mm; upper layer, 2 × 2 mm; Tetko, Kansas City, MO). These collagen/mesh rafts (referred to hereafter as implants) were then placed at 37.5°C for 1.5 hours to allow for collagen polymerization into fibrils.

Using jeweler's forceps, the fibrillar collagen implants were placed on the CAM of a day 10 chick embryo (Figure 1A,B). Four implants were placed on each CAM with at least one control (no addition) and one growth factor–containing implant per embryo. Embryos were removed from the incubator on day 13 and viewed through a stereomicroscope (Olympus, Melville, NY); distinct blood vessels appearing in the collagen matrix at or above the plane of the top mesh were identified (Figure1C,D). Each box in the top mesh grid was scored for the presence or absence of vessels to give a proportion of positive boxes/total boxes counted (referred to as the angiogenesis score).

Immunofluorescent staining of tissue sections

Implants were dissected from the CAM and snap-frozen in OCT freezing medium (Tissue Tek; Miles, Elkhart, IN). Twenty-micron cryosections were cut, placed on poly-l-lysine–coated slides, and stored at −80°C. Slides were thawed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed 3 × in PBS, and blocked in PBS/10% normal goat serum (NGS), prior to incubation with primary antibodies. Monoclonal antibody 1A4 against α-smooth muscle actin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) (1 μg/mL) was diluted in PBS/10% NGS and incubated on cryosections overnight at 4°C. Staining for the chicken MMP-9–like enzyme was performed using an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (0.3 μg/mL).28 Staining for chick MMP-2 was performed using an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (0.5 μg/mL).28 Sections were incubated with goat antimouse IgG or goat antirabbit IgG conjugated with the red fluorochrome Alexa 546 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), diluted 1:1000 in PBS/10% NGS with 2 mg/mL RNase A (Labscientific, Livingston, NJ). The Renaissance Tyramide Signal Amplification Kit (NEN, Boston, MA) was used according to the manufacturer's directions (with the exception described below) for detection of the following antibodies: rabbit antihuman von Willebrand factor (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) at a dilution of 1:7000, mouse monoclonal CVI-ChNL-68.1 (ID-DLO, Lelystad, The Netherlands) against chicken macrophages (1:10 000 dilution), and mouse monoclonal 5H6 against Quek-1/VEGFR2 (a gift of Dr Anne Eichmann) at a dilution of 1:100.29 The red fluorochrome Alexa 546 conjugated to streptavidin (Molecular Probes) was diluted 1:1500 and substituted for streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase at the last step of the detection protocol. Sections were incubated with 2 mg/mL RNase A (Labscientific) for 2 hours prior to mounting. Finally, all sections were mounted in ProLong antifade reagent, containing the green nucleic acid stain YO-PRO-1 iodide at 1:400 (Molecular Probes). Fluorescent images were captured in grayscale on a Zeiss Axioskop fitted with a cooled CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Images were subsequently processed and colorized using Adobe Photoshop 5.5.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

Collagen implants were dissected from the CAM and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was purified from the implants using a Total RNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed to first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) in 20 μL 0.01 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 0.05 M KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dNTP, 0.01 M DTT, 25 μM random hexamer primers, and 10 U/μL Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The reactions were incubated at 42°C for 50 minutes. After cDNA synthesis, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out by the following program: incubation at 94°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C for denaturation, 30 seconds at 50°C for annealing, and 30 seconds at 72°C for elongation. To produce specific PCR product for chicken MT3-MMP (cMMP-16)30 and chicken MMP-13 (cMMP-13),31 specific primers were designed based on the reported sequences. For cMMP-16, the forward primer is 5′ AGAATCACCCCAGGGAGCCTTTGT 3′ (position 1572-1595 bp) and the reverse primer is 5′ GATCTCACCCACTCTTGCATAGAGCGT 3′ (position 1917-1944 bp). The PCR product is 375 bp. For cMMP-13, the forward primer is 5′ GGTCAGATGATTCTAGAGGGT 3′ (position 341-361 bp) and the reverse primer is 5′ CAACTATGTCATAGCCATTCATAG 3′ (position 787-810 bp). The PCR product is 469 bp. The PCR samples were analyzed by 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Collagen digestion

Lyophilized WT and homozygous mutant collagenase–resistant (r/r) collagens were resuspended in 0.5 N acetic acid and centrifuged to remove insoluble material. Purified TIMP-free chicken MMP-2 was isolated by gelatin-Sepharose chromatography as described previously.32 Triple-helical collagen cleavage assays were performed in calcium assay buffer (CAB), composed of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35. Twenty micrograms WT or r/r mouse collagen was incubated for 18 hours at 24°C in the presence or absence of 0.5 μg purified chick MMP-2 or human MMP-1 (Chemicon, Temecula, CA), activated for 1 hour with 2 mM p-aminophenylmercuric acetate (APMA) at 37°C. For gelatin cleavage, WT or r/r collagens were heated to 60°C for 15 minutes for denaturation (gelatinization) prior to incubation with chick MMP-2 (0.05 μg). Gelatinolytic cleavage was performed at 37°C and reactions were stopped by addition of EDTA to 50 mM. Samples were analyzed by reducing sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and visualized by Coomassie staining.

Statisticalanalysis

The SPSS Base 9.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for data analysis. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparisons of embryo-matched angiogenesis scores between treatment conditions. Group means and SEs were used for graphical depiction of the data. For quantitation of total cellularity, microscopic images were analyzed using Metamorph software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA). A Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric data was used for statistical comparison of image analysis data of total cellularity.

Results

Growth factor stimulation of blood vessel growth using a modified angiogenesis assay

Angiogenesis assays were performed by modifying a technique25 in which a fibrillar type I collagen gel is cast around 2 layers of nylon mesh and implanted onto the CAM of chick embryos as described in “Materials and methods” (Figure 1A,B). This procedure, unlike other techniques using the CAM, unambiguously eliminates the interference of preexisting blood vessels, one of the major confounding variables in many studies of angiogenesis in vivo.24 A large number of new microvessels (5-40 μm in diameter) that actually can be viewed in the live embryo (Figure 1C,D) were very apparent in a growth factor–treated implant, compared to those treated with buffer alone. Underlying vessels, preexisting in the CAM before implantation, are barely visible and out of the plane of focus by a distance of more than 200 μm (open circles in Figure 1C,D). These preexisting vessels are not scored in this assay system but may be counted erroneously in the more commonly used CAM angiogenesis assays23 24 that do not require growth into a new plane of focus. The well-delineated neovessels (arrowheads in Figure 1D), which are easily scored within the grids of the nylon mesh, provide for quantitation in the assay.

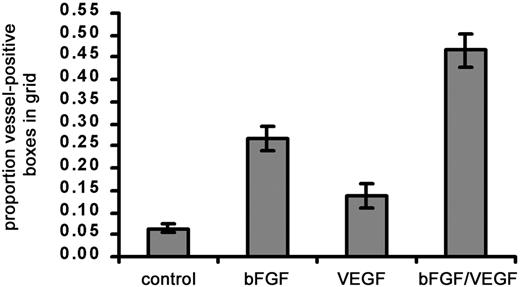

In initial experiments using the modified CAM assay, we found that a significant angiogenic response occurred when bFGF alone (∼4-fold stimulation) was added to the collagen implants (Figure2). Under similar conditions, the original methodology yielded only a 2- to 2.5-fold stimulation with bFGF added to the collagen implant.25 VEGF alone added to the implant results in a 2-fold stimulation. However, maximal angiogenesis (7- to 10-fold) occurs when bFGF is combined with VEGF (Figure 2). The original description of this angiogenesis assay did not report any utilization of combined growth factors.25 Thus, the effect of the combined growth factors was significantly greater than that of either one alone. These data are consistent with reports of the synergistic, angiogenic effects of bFGF and VEGF in vivo.33 34 We therefore chose to use a combination of bFGF and VEGF in subsequent experiments.

Effect of angiogenic growth factors on vascularization of type I collagen implants.

Three different treatments, namely, bFGF (0.5 μg), VEGF (0.15 μg), or bFGF + VEGF were tested for their ability to stimulate a strong angiogenic response within collagen implants. Collagen was copolymerized with buffer alone or with growth factors prior to placement on the CAM. After 66 hours on the CAM, angiogenesis scores were measured and calculated as the proportion (mean ± SEM) of positive boxes in the upper nylon mesh grid. Data represent 3 pooled experiments: control, n = 37 implants; bFGF, n = 37; VEGF, n = 21; and bFGF/VEGF, n = 37. Results of statistical analysis performed using Wilcoxon signed rank test on matched pairs are as follows: bFGF versus buffer control, P < .001; VEGF versus buffer control, P > .05; bFGF/VEGF versus buffer control, P < .001; and bFGF/VEGF versus VEGF or bFGF,P < .001.

Effect of angiogenic growth factors on vascularization of type I collagen implants.

Three different treatments, namely, bFGF (0.5 μg), VEGF (0.15 μg), or bFGF + VEGF were tested for their ability to stimulate a strong angiogenic response within collagen implants. Collagen was copolymerized with buffer alone or with growth factors prior to placement on the CAM. After 66 hours on the CAM, angiogenesis scores were measured and calculated as the proportion (mean ± SEM) of positive boxes in the upper nylon mesh grid. Data represent 3 pooled experiments: control, n = 37 implants; bFGF, n = 37; VEGF, n = 21; and bFGF/VEGF, n = 37. Results of statistical analysis performed using Wilcoxon signed rank test on matched pairs are as follows: bFGF versus buffer control, P < .001; VEGF versus buffer control, P > .05; bFGF/VEGF versus buffer control, P < .001; and bFGF/VEGF versus VEGF or bFGF,P < .001.

An array of cell types, both endothelial and stromal, invade the collagen implants

To examine new blood vessel growth in more detail, immunostaining of the collagen implants and underlying CAM tissue was carried out using an antibody to avian VEGF-R2, a specific endothelial cell and hemangioblast marker.29 In sections through samples harvested after only 24 hours on the CAM, neither positively staining, vessel-like structures nor isolated endothelial cells were observed within the implants (Figure 3A,B). A network of fine capillaries, the subectodermal vascular plexus, stained positively and was delineated just below the interface between the implant and the CAM (asterisks in Figure 3A,B). Deep in the CAM mesoderm, large vessels with a circumscribed lumen (lu) also stained positively. After 48 hours, the subectodermal plexus appeared distorted giving rise to the first endothelial sprouts entering the implants (arrows in Figure 3C,D). The sprouts appeared with greater frequency and in a more upward position vertically in the bFGF/VEGF-treated implants. By 66 hours, the time at which angiogenesis scores were measured, a substantial increase in the number of positively stained vessels was observed in the upper grid of the growth factor–treated implant (Figure 3E,F). It is clear from this time course that the visual scoring technique in the assay (Figure 1) accurately reflects a rapid and extensive infiltration of newly formed endothelium into fibrillar collagen in response to bFGF and VEGF.

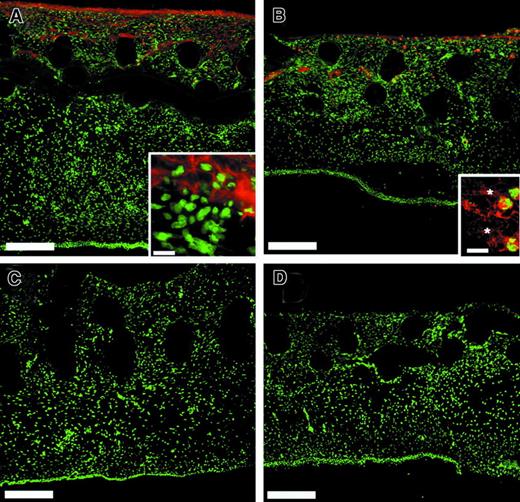

Effect of angiogenic growth factors on endothelial cell invasion and vessel formation.

Collagen implants and underlying tissues were harvested from the CAM at 24 hours (A,B), 48 hours (C,D), or 66 hours (E,F), cryosectioned, and processed for immunohistochemistry. Endothelial markers (red) were detected by immunofluorescence in sections from implants that had been treated with buffer alone (A,C,E) or bFGF/VEGF (B,D,F). Sections were counterstained for nuclei (green). Immunostaining was performed using anti-VEGFR2/QUEK-1 IgG in conjunction with an amplification system, as described in “Materials and methods.” The subectodermal vascular plexus across the top of the CAM was apparent at 24 hours (asterisks in A,B) and was no longer discernible by 66 hours. New vascular sprouts (red endothelial staining) began to appear within the implants by 48 hours (C,D), with a clear angiogenic response seen at 66 hours (E,F). Arrows indicate some of the vascular sprouts that have entered the grids of the upper nylon mesh (clear circles) of the collagen implant. Large CAM blood vessels (lu) were frequently packed with nucleated red blood cells. Bar indicates 200 μm. Inset in panel F shows both blood vessels (lu) clearly containing nucleated red blood cells (green) and also endothelial staining that is not associated with an obvious lumen (arrowheads).

Effect of angiogenic growth factors on endothelial cell invasion and vessel formation.

Collagen implants and underlying tissues were harvested from the CAM at 24 hours (A,B), 48 hours (C,D), or 66 hours (E,F), cryosectioned, and processed for immunohistochemistry. Endothelial markers (red) were detected by immunofluorescence in sections from implants that had been treated with buffer alone (A,C,E) or bFGF/VEGF (B,D,F). Sections were counterstained for nuclei (green). Immunostaining was performed using anti-VEGFR2/QUEK-1 IgG in conjunction with an amplification system, as described in “Materials and methods.” The subectodermal vascular plexus across the top of the CAM was apparent at 24 hours (asterisks in A,B) and was no longer discernible by 66 hours. New vascular sprouts (red endothelial staining) began to appear within the implants by 48 hours (C,D), with a clear angiogenic response seen at 66 hours (E,F). Arrows indicate some of the vascular sprouts that have entered the grids of the upper nylon mesh (clear circles) of the collagen implant. Large CAM blood vessels (lu) were frequently packed with nucleated red blood cells. Bar indicates 200 μm. Inset in panel F shows both blood vessels (lu) clearly containing nucleated red blood cells (green) and also endothelial staining that is not associated with an obvious lumen (arrowheads).

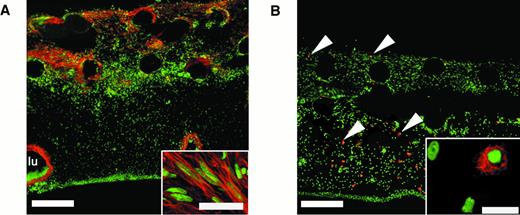

To examine the overall cellular content of the vascularized collagen implants, further histologic analysis was performed on cryosections through the implants. In tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin, we observed extensive cellular invasion into the collagen implants, and an array of nonendothelial cell types was consistently found (data not shown). Abundant fibroblast-like cells, likely myofibroblasts, were apparent, as indicated by labeling with an antibody to α-smooth muscle actin (Figure 4A). These activated fibroblasts appeared more in the upper regions of the collagen implant where new vessels were forming. The presence of macrophages in the collagen implants was indicated by means of a chicken macrophage–specific monoclonal antibody (CVI-ChNL-68.1),35 which identified a population of cells present throughout the implant that were tissue macrophage–like in appearance (Figure 4B, inset). Polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) were additional components of the implant tissue and underlying CAM. These cells, known as heterophils, appeared in the upper regions of the CAM and in the implants as early as 24 hours after implantation, well before the appearance of endothelial cells and activated fibroblasts (data not shown). Thus, the formerly cell-free collagen implant became rapidly populated by distinct cell types during the 3 days required for extensive vascularization. This suggests that the fibrillar type I collagen implant provides a good, physiologic matrix for rapid engraftment by host stromal cells, inflammatory cells, and newly formed blood vessels.

An array of nonendothelial cell types is present in vascularized collagen implants after incubation on the CAM.

Twenty-micron cryosections through bFGF/VEGF-treated collagen implants were stained using cell type–restricted antibodies (red) and counterstained for nuclei (green). (A) Anti–α-smooth muscle actin stains fibroblastic cells (myofibroblasts) that appear in the upper regions of the implant. Bar indicates 200 μm. Individual myofibroblast-like cells, oriented in parallel, are shown at higher magnification (inset; bar, 10 μm). A large blood vessel lumen (lu) is lined by α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells. (B) Antibody CVI-ChNL-68.1, a marker for chicken macrophages, identifies specific cells that are present throughout the vascularized implant (arrowheads). Bar indicates 200 μm. At higher magnification, these cells are tissue macrophage–like in appearance (inset; bar, 20 μm).

An array of nonendothelial cell types is present in vascularized collagen implants after incubation on the CAM.

Twenty-micron cryosections through bFGF/VEGF-treated collagen implants were stained using cell type–restricted antibodies (red) and counterstained for nuclei (green). (A) Anti–α-smooth muscle actin stains fibroblastic cells (myofibroblasts) that appear in the upper regions of the implant. Bar indicates 200 μm. Individual myofibroblast-like cells, oriented in parallel, are shown at higher magnification (inset; bar, 10 μm). A large blood vessel lumen (lu) is lined by α-smooth muscle actin-positive cells. (B) Antibody CVI-ChNL-68.1, a marker for chicken macrophages, identifies specific cells that are present throughout the vascularized implant (arrowheads). Bar indicates 200 μm. At higher magnification, these cells are tissue macrophage–like in appearance (inset; bar, 20 μm).

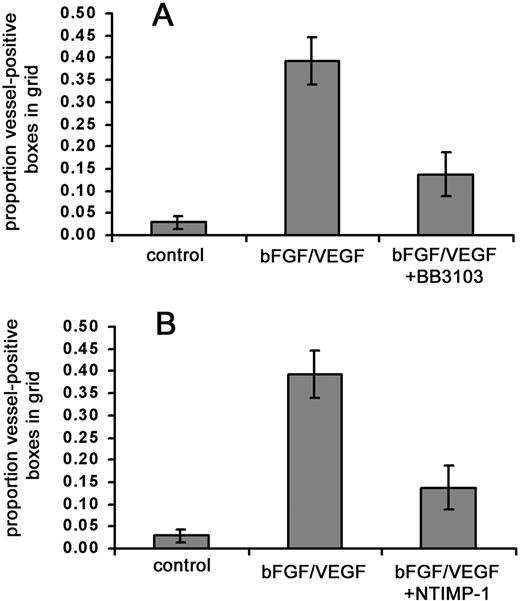

Growth factor–induced vascularization of collagen implants depends on MMP activity

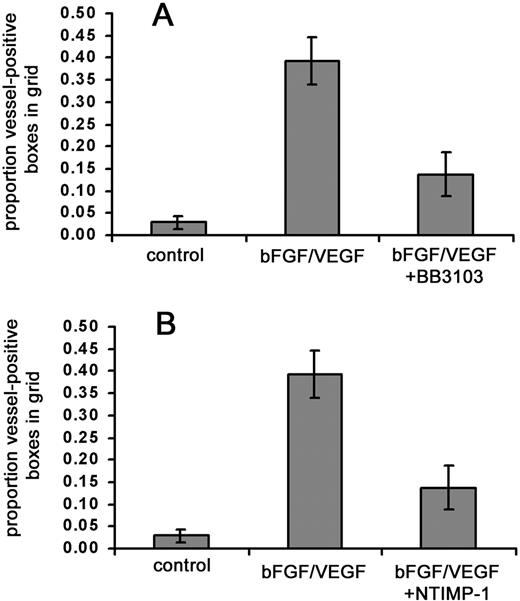

Remodeling of interstitial matrix proteins, such as type I collagen, is thought to be important in many forms of angiogenesis and is mediated to a significant extent by members of the MMP family.4,36 Therefore, we wanted to determine if in vivo vascularization of the collagen implants requires metalloproteinase activity. We first tested a broadly acting, synthetic metalloproteinase inhibitor, BB-3103. Repeated doses (0.2-1.4 μg) of the inhibitor were given because in the shell-less embryo system, topical application of experimental compounds can be conducted with relative ease. Under these conditions, the addition of BB-3103 resulted in a large (> 65%) decrease in the amount of stimulated angiogenesis (Figure5A). We also examined the effects of a natural MMP inhibitor, TIMP-1, as an alternative to the synthetic inhibitor. Collagen implants were treated with a recombinant C–terminally truncated form of TIMP-1 (N-TIMP-1) that retains MMP-inhibitory activity.27 In the presence of growth factors and N-TIMP-1, angiogenesis scores also were substantially (> 60%) reduced (Figure 5B). These results provide evidence that one or more MMPs are involved in the observed neovascularization.

Synthetic and natural MMP inhibitors substantially reduce growth factor–stimulated angiogenesis.

Collagen was copolymerized with buffer alone, bFGF/VEGF, or bFGF/VEGF plus indicated metalloproteinase inhibitors, prior to placement of the collagen implant on the chick CAM. The embryos containing the implants were incubated for 66 hours, with topical addition of inhibitors at 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours. At the end of the incubation, the new vessels appearing in the collagen implants were scored as described in “Materials and methods.” (A) MMP inhibitor BB3103 was added at an initial dose of 1.4 μg/implant with 4 subsequent topical doses of 0.24 μg each. Data represent 2 pooled experiments: control, n = 15 implants; bFGF/VEGF, n = 16; and bFGF/VEGF/BB3103, n = 16. Results of statistical analysis performed using Wilcoxon-signed rank test on matched pairs are as follows: bFGF/VEGF versus buffer control,P = .001; bFGF/VEGF versus bFGF/VEGF/BB3103,P < .01, and buffer control versus bFGF/VEGF/BB3103,P > .05. (B) NTIMP-1 was added at an initial dose of 1.8 μg/implant with 4 subsequent topical doses of 1.8 μg each. Data represent 4 pooled experiments: control, n = 25 implants; bFGF/VEGF, n = 27; and bFGF/VEGF/NTIMP-1, n = 27. Results of statistical analysis are as follows: bFGF/VEGF versus buffer control,P < .001; bFGF/VEGF versus bFGF/VEGF/NTIMP-1,P < .001; buffer control versus bFGF/VEGF/NTIMP-1,P < .05.

Synthetic and natural MMP inhibitors substantially reduce growth factor–stimulated angiogenesis.

Collagen was copolymerized with buffer alone, bFGF/VEGF, or bFGF/VEGF plus indicated metalloproteinase inhibitors, prior to placement of the collagen implant on the chick CAM. The embryos containing the implants were incubated for 66 hours, with topical addition of inhibitors at 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours. At the end of the incubation, the new vessels appearing in the collagen implants were scored as described in “Materials and methods.” (A) MMP inhibitor BB3103 was added at an initial dose of 1.4 μg/implant with 4 subsequent topical doses of 0.24 μg each. Data represent 2 pooled experiments: control, n = 15 implants; bFGF/VEGF, n = 16; and bFGF/VEGF/BB3103, n = 16. Results of statistical analysis performed using Wilcoxon-signed rank test on matched pairs are as follows: bFGF/VEGF versus buffer control,P = .001; bFGF/VEGF versus bFGF/VEGF/BB3103,P < .01, and buffer control versus bFGF/VEGF/BB3103,P > .05. (B) NTIMP-1 was added at an initial dose of 1.8 μg/implant with 4 subsequent topical doses of 1.8 μg each. Data represent 4 pooled experiments: control, n = 25 implants; bFGF/VEGF, n = 27; and bFGF/VEGF/NTIMP-1, n = 27. Results of statistical analysis are as follows: bFGF/VEGF versus buffer control,P < .001; bFGF/VEGF versus bFGF/VEGF/NTIMP-1,P < .001; buffer control versus bFGF/VEGF/NTIMP-1,P < .05.

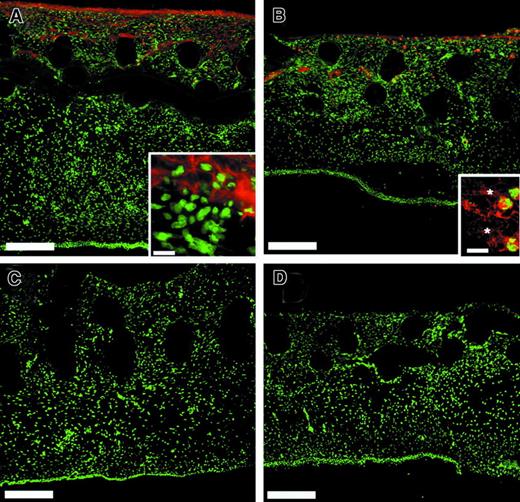

Because CAM angiogenesis appears to depend in part on MMP activity, it was of interest to determine which MMPs may contribute to the observed requirement. Several approaches were used for the detection within CAM/implant tissue of chicken MMPs, for which suitable species-specific reagents are not widely available. Our laboratory had originally cloned chicken MMP-237 and recombinant expression of this enzyme allowed for the production of an antibody highly specific for chicken MMP-2. Immunostaining of 66-hour CAM tissue/implants with the antichicken MMP-2 revealed that MMP-2 was indeed present in the angiogenic tissue and was confined almost exclusively to the upper part of the implant (Figure 6A). This predominance of signal in the upper region of the implant and near absence in the lower CAM tissue is similar to the distribution of the marker for myofibroblasts (Figure 4A). However, the anti–MMP-2 staining does not appear to be confined solely to a specific cell type, but mostly appears pericellular, more associated with fibril-like structures of the collagen implant tissue (inset, Figure 6A). The pattern of staining for MMP-2 appeared similar in implants that were not treated with bFGF/VEGF (data not shown) and thus MMP-2 does not appear specifically in the implants in response to angiogenic growth factors.

Multiple MMPs are present in the collagen implants after incubation on the CAM.

Embryos containing the collagen implants were incubated for 66 hours before harvesting. Twenty-micron cryosections through bFGF/VEGF-treated collagen implants were stained using affinity-purified MMP-specific antibodies (red) and counterstained for nuclei (green). (A) Chicken MMP-2 appears in a pericellular pattern within the extracellular matrix. Bar indicates 200 μm. Inset, bar indicates 20 μm. (B) The chicken MMP-9–like enzyme is associated with both PMNs and the extracellular matrix. Bar indicates 200 μm. In the inset, individual positively stained PMNs are enmeshed in a positively staining matrix (asterisks). Bar indicates 10 μm. The affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies were subjected to immunodepletion using purified antigens prior to staining to demonstrate the specificity of the MMP-2 (C) or MMP-9 (D) signals. For depletion of antibodies, purified MMP-2, or MMP-9, was electrophoresed and transferred to nitrocellulose. The nitrocellulose strips were blocked with serum and incubated overnight with dilute solutions of affinity-purified anti–MMP-2 or anti–MMP-9 antibody. The adsorbed antibody solutions were used for immunostaining and yielded no signal (C, D).

Multiple MMPs are present in the collagen implants after incubation on the CAM.

Embryos containing the collagen implants were incubated for 66 hours before harvesting. Twenty-micron cryosections through bFGF/VEGF-treated collagen implants were stained using affinity-purified MMP-specific antibodies (red) and counterstained for nuclei (green). (A) Chicken MMP-2 appears in a pericellular pattern within the extracellular matrix. Bar indicates 200 μm. Inset, bar indicates 20 μm. (B) The chicken MMP-9–like enzyme is associated with both PMNs and the extracellular matrix. Bar indicates 200 μm. In the inset, individual positively stained PMNs are enmeshed in a positively staining matrix (asterisks). Bar indicates 10 μm. The affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies were subjected to immunodepletion using purified antigens prior to staining to demonstrate the specificity of the MMP-2 (C) or MMP-9 (D) signals. For depletion of antibodies, purified MMP-2, or MMP-9, was electrophoresed and transferred to nitrocellulose. The nitrocellulose strips were blocked with serum and incubated overnight with dilute solutions of affinity-purified anti–MMP-2 or anti–MMP-9 antibody. The adsorbed antibody solutions were used for immunostaining and yielded no signal (C, D).

Our laboratory has recently detected, cloned, and purified an MMP-9–like, 75-kd gelatinase.28 This chicken MMP was shown to be present only in bone marrow cells, some tissue monocytes, and most heterophils, the avian equivalent of PMNs. When a specific antibody to the enzyme was used to probe CAM/implant tissue, immunostaining was primarily associated with cells that possessed multilobed nuclei (Figure 6B). These heterophils appeared mainly in the upper portion of the implant and more sparsely throughout the entire CAM tissue. Some immunostaining for the 75-kd gelatinase also appeared extracellularly on fibril-like structures (Figure 6B, inset). In contrast to MMP-2, immunostaining for the 75-kd gelatinase does appear to be more intense in the bFGF/VEGF-treated implants and also does appear as early as 24 hours (data not shown). The specificity of the staining for the MMP-2 and the MMP-9–like gelatinase is demonstrated by the absence of stain following absorption of the respective antibody with purified enzymes (Figure 6C,D).

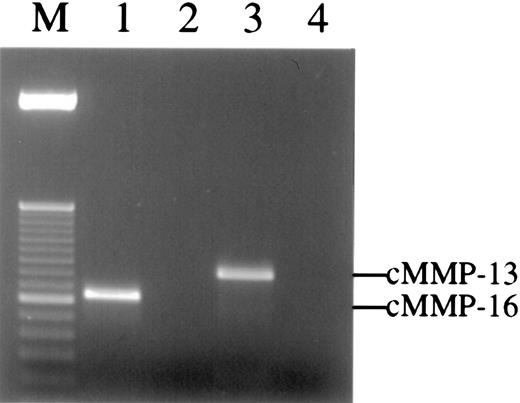

Three other chicken MMP family members have been characterized and cloned, namely, chicken MMP-13,31 MMP-16 (MT3-MMP),30 and MMP-22.38 Unfortunately, no highly specific antibodies for these enzymes are yet available. To determine if these MMPs are present in the angiogenic CAM tissue, reverse transcription– polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out on RNA isolated from 66-hour CAM implants. Enzyme-specific primers were designed based on the reported sequences for the chicken MMPs. The results demonstrate that the messenger RNA (mRNA) for both chicken MMP-13 and MMP-16 are present in CAM tissue at the time of new vessel scoring (Figure 7), whereas no PCR signal was observed for chicken MMP-22 (data not shown). Furthermore, the mRNA levels for both enzymes increase from 24 to 66 hours after placement of the collagen implant, and bFGF/VEGF treatment also appears to enhance the levels of the respective mRNAs (data not shown).

Multiple MMPs are detected in the collagen implants by RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from collagen implants harvested from embryos at 66 hours. Reverse transcription reactions were performed with or without Superscript reverse transcriptase. The PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel and detected by ethidium bromide staining. Single bands of 375 bp and 469 bp were detected in RT-PCR using cMMP-16 (lane 1) or cMMP-13 (lane 3) gene-specific primers, respectively. In contrast, no bands could be amplified from control samples containing no reverse transcriptase but containing either cMMP-16 (lane 2) or cMMP-13 (lane 4) gene-specific primers. The PCR products in lanes 1 to 3 were cloned and sequenced and manifest 100% homology with chicken MMP-16 and MMP-13, respectively. Lane M is 50-bp ladder DNA size marker.

Multiple MMPs are detected in the collagen implants by RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from collagen implants harvested from embryos at 66 hours. Reverse transcription reactions were performed with or without Superscript reverse transcriptase. The PCR products were analyzed by 2% agarose gel and detected by ethidium bromide staining. Single bands of 375 bp and 469 bp were detected in RT-PCR using cMMP-16 (lane 1) or cMMP-13 (lane 3) gene-specific primers, respectively. In contrast, no bands could be amplified from control samples containing no reverse transcriptase but containing either cMMP-16 (lane 2) or cMMP-13 (lane 4) gene-specific primers. The PCR products in lanes 1 to 3 were cloned and sequenced and manifest 100% homology with chicken MMP-16 and MMP-13, respectively. Lane M is 50-bp ladder DNA size marker.

Collagenase-resistant collagen constitutes a defective substratum for angiogenesis in vivo

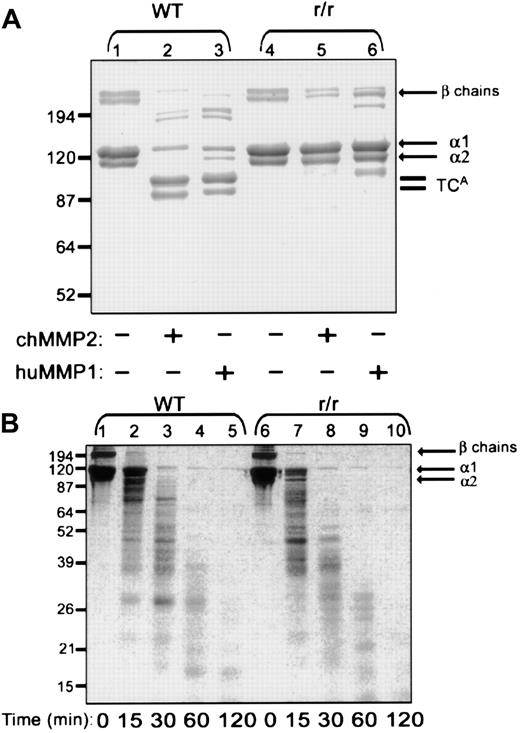

To address the specific substrate preferences of the proteolytic activities required for growth factor–stimulated angiogenesis, a unique, genetically engineered variant of the type I collagen substrate was used. Collagen from homozygous mutant r/r mice contains α(I) chains bearing helix-stabilizing amino acid changes in the triple helical cleavage site.22 We first asked whether the r/r collagen was resistant to MMP-2, previously shown to have interstitial collagenase activity.32 MMP-1 also was examined as the prototypical interstitial collagenase. A collagen cleavage assay was performed using triple-helical, native, dermal collagen (Figure8A). At a temperature of 24°C, treatment of WT collagen with either recombinant MMP-2 or recombinant MMP-1 yielded the characteristic three-quarter length fragment (Figure8A, lanes 2-3). The r/r collagen was resistant to cleavage by both MMP-1 (lane 6) and MMP-2 (lane 5). These data not only verify that the r/r collagen is collagenase resistant but affirm that MMP-2 can function as an interstitial collagenase and cannot cleave r/r collagen.

Native r/r collagen forms fibrils similar to WT collagen but, unlike WT collagen, cannot be cleaved by interstitial collagenases.

(A) Native WT or r/r collagens (20 μg) were incubated in CAB for 18 hours at 24°C with or without 0.5 μg MMP-1 or MMP-2 that had been preactivated for 1 hour with 2 mM APMA at 37°C. Following incubation, the proteins were separated by reducing 8% SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie blue. Three-quarter length fragments (TCAfragments) appear in the collagenase-treated WT samples (lanes 2 and 3) but not in r/r samples (lanes 5 and 6). (B) WT or r/r collagens (20 μg) were heated to 60°C for 15 minutes to form gelatin prior to incubation with preactivated MMP-2 (0.5 μg) in CAB for the indicated times. Samples (20 μg) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and visualized with Coomassie blue. A similar pattern of proteolytic fragments appears when heat-denatured WT or r/r collagen was treated with the MMP-2 gelatinase, indicating that the unique specificity in the r/r collagen lies in its resistance only to interstitial collagenases shown in panel A.

Native r/r collagen forms fibrils similar to WT collagen but, unlike WT collagen, cannot be cleaved by interstitial collagenases.

(A) Native WT or r/r collagens (20 μg) were incubated in CAB for 18 hours at 24°C with or without 0.5 μg MMP-1 or MMP-2 that had been preactivated for 1 hour with 2 mM APMA at 37°C. Following incubation, the proteins were separated by reducing 8% SDS-PAGE and visualized with Coomassie blue. Three-quarter length fragments (TCAfragments) appear in the collagenase-treated WT samples (lanes 2 and 3) but not in r/r samples (lanes 5 and 6). (B) WT or r/r collagens (20 μg) were heated to 60°C for 15 minutes to form gelatin prior to incubation with preactivated MMP-2 (0.5 μg) in CAB for the indicated times. Samples (20 μg) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and visualized with Coomassie blue. A similar pattern of proteolytic fragments appears when heat-denatured WT or r/r collagen was treated with the MMP-2 gelatinase, indicating that the unique specificity in the r/r collagen lies in its resistance only to interstitial collagenases shown in panel A.

To verify that the helix-stabilizing amino acid changes in the r/r collagen would not affect proteolysis at other sites within the collagen molecule, a gelatinase assay was performed using heat-denatured WT and r/r collagens (Figure 8B). Treatment of WT (lanes 1-5) and r/r (lanes 6-10) denatured collagen (gelatin) with MMP-2 at 37°C yielded a similar time course and a similar pattern of gelatin cleavage products. These data, demonstrating equal susceptibility of WT and r/r collagens to gelatinases, indicate that the specificity of the r/r mutant resides in its unique resistance only to interstitial collagenases. It was found previously that the melting point of the collagenase-resistant collagen also does not differ from WT.21 Furthermore, at the light microscopic level, the density and pattern of formed fibrils appeared identical. The 2 collagen variants were also indistinguishable at the ultrastructural level, indicating no difference in morphology of individual fibrils (data not shown). These data indicate that the collagenase-resistant mutant is otherwise identical to WT.

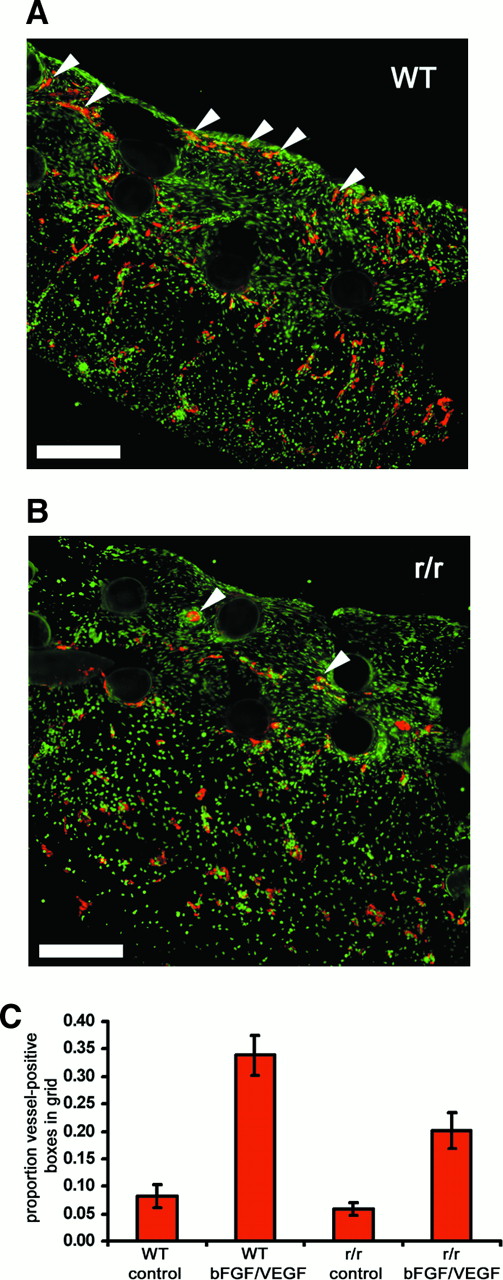

Either collagenase-resistant type I collagen or the strain-matched WT control was used to prepare implants for the angiogenesis assay. Immunohistochemical analysis of these tissues, using antibodies to the endothelial marker, von Willebrand factor, revealed numerous nascent vessels in bFGF/VEGF-treated WT collagen implants (Figure9A) but scant vessels in bFGF/VEGF-treated collagenase-resistant implants (Figure 9B). Not only were there fewer newly formed vessels in the r/r implants, but the influx of cells labeling with the endothelial marker appeared to be diminished throughout the r/r implants. We therefore decided to look at the large set of embryos bearing WT or r/r implants. Relative to buffer controls, WT mouse collagen stimulated with bFGF/VEGF was an effective substratum for neovascularization (Figure 9C), yielding a mean score of 35% vessel-positive grids. However, significantly reduced levels of new blood vessel growth (19% vessel-positive grids) were observed in collagenase-resistant collagen implants in response to stimulation by growth factors. Background levels of vascularization in buffer-treated, r/r mutant implants were slightly reduced compared to WT, but this effect was not statistically significant.

Collagenase-resistant collagen is a deficient substratum for growth factor–stimulated angiogenesis.

WT or collagenase-resistant, r/r collagen at equal concentrations was copolymerized with buffer alone or bFGF/VEGF, prior to placement on the chick CAM. The embryos containing the collagen implants were incubated for 66 hours. Immunofluorescent detection of endothelial marker von Willebrand factor in cryosectioned implants prepared from (A) WT collagen treated with bFGF/VEGF or (B) r/r collagen treated with bFGF/VEGF revealed decreased endothelial staining (red) and fewer vessel-like structures within the upper portion of r/r implants. The arrowheads indicate only some of the endothelial cell–containing vascular structures. Bar indicates 200 μm. (C) Results from a large series of CAM assays supported the histologic observation in panels A and B that r/r implants display reduced angiogenesis. Data represent 4 pooled experiments: WT alone, n = 35 implants; WT + bFGF/VEGF, n = 40; r/r alone, n = 34; and r/r + bFGF/VEGF, n = 45. Results of statistical analysis performed using Wilcoxon-signed rank test on matched pairs are as follows: WT alone versus WT + bFGF/VEGF, P < .001; r/r alone versus r/r + bFGF/VEGF, P < .01; WT + bFGF/VEGF versus r/r + bFGF/VEGF, P < .01; and WT alone versus r/r alone,P > .05.

Collagenase-resistant collagen is a deficient substratum for growth factor–stimulated angiogenesis.

WT or collagenase-resistant, r/r collagen at equal concentrations was copolymerized with buffer alone or bFGF/VEGF, prior to placement on the chick CAM. The embryos containing the collagen implants were incubated for 66 hours. Immunofluorescent detection of endothelial marker von Willebrand factor in cryosectioned implants prepared from (A) WT collagen treated with bFGF/VEGF or (B) r/r collagen treated with bFGF/VEGF revealed decreased endothelial staining (red) and fewer vessel-like structures within the upper portion of r/r implants. The arrowheads indicate only some of the endothelial cell–containing vascular structures. Bar indicates 200 μm. (C) Results from a large series of CAM assays supported the histologic observation in panels A and B that r/r implants display reduced angiogenesis. Data represent 4 pooled experiments: WT alone, n = 35 implants; WT + bFGF/VEGF, n = 40; r/r alone, n = 34; and r/r + bFGF/VEGF, n = 45. Results of statistical analysis performed using Wilcoxon-signed rank test on matched pairs are as follows: WT alone versus WT + bFGF/VEGF, P < .001; r/r alone versus r/r + bFGF/VEGF, P < .01; WT + bFGF/VEGF versus r/r + bFGF/VEGF, P < .01; and WT alone versus r/r alone,P > .05.

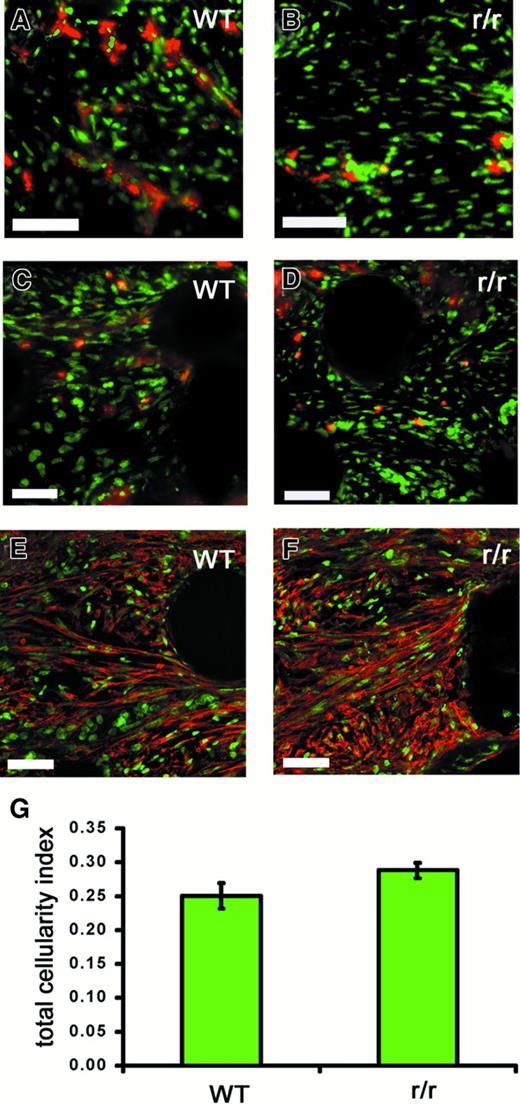

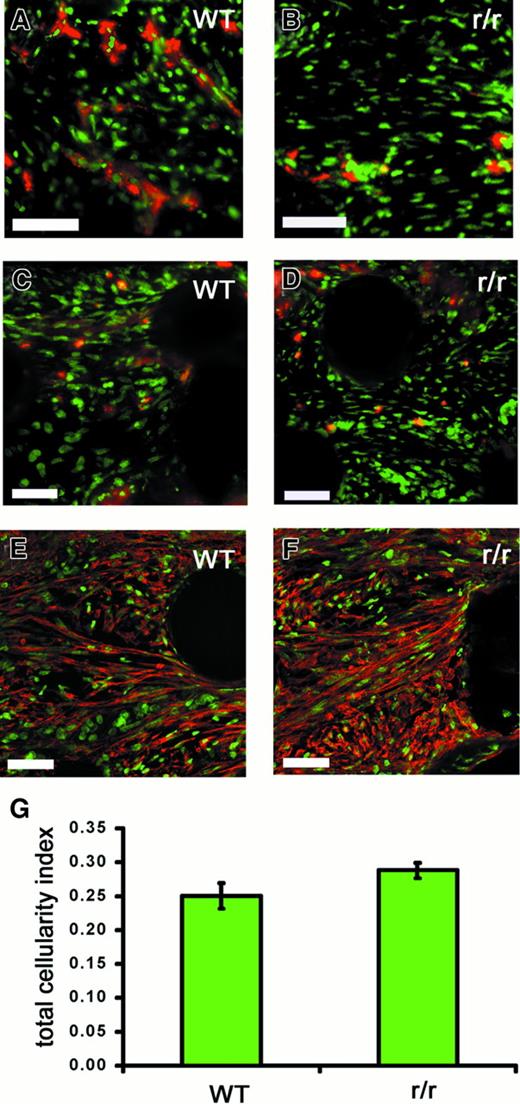

To examine whether the observed deficiency of angiogenesis in r/r implants could be simply due to the inability of cells in general to invade a noncleavable matrix, we performed a multicellular histologic analysis of WT and collagenase-resistant implants that had been treated with bFGF/VEGF (Figure 10). Although endothelial staining in the implants was clearly decreased in the r/r compared to WT (Figure 10A), this was not the case for other cell types examined. Similar numbers of heterophils, as indicated by staining for the chicken 75-kd gelatinase (Figure 10C,D), myofibroblasts, as indicated by staining for α-smooth muscle actin (Figure 10E,F), and macrophages (data not shown) were found in collagenase-resistant and WT implants. Finally, analysis of total nuclear staining in the implants revealed no difference in total cellularity (Figure 10G). Taken together, these data suggest that a collagenase-resistant matrix specifically impedes invasion of endothelial cells, and therefore blood vessel formation, but not the invasion of other cell types.

Collagenase-resistant implants exhibit a deficiency of endothelial cells but not other cell types.

WT or collagenase-resistant, r/r collagen at equal concentrations was copolymerized with buffer alone or bFGF/VEGF, prior to placement on the chick CAM. The embryos containing the collagen implants were incubated for 66 hours. Immunofluorescent detection of multiple cell types revealed a deficiency only of endothelial cells in collagenase-resistant (B,D,F) compared to WT (A,C,E) implants. Staining is shown for the endothelial cells with anti–von Willebrand factor (A,B), PMN heterophils with antichicken MMP-9 (C,D), or myofibroblasts with antismooth muscle actin (E,F). Bar indicates 50 μm. (G) Total cellularity was similar between collagenase-resistant and WT implants, as indicated by image analysis of total nuclear staining in the upper region of the implants. Data shown in bar graphs are the average of 5 independent samples ± SEM Mann-Whitney U test: n = 5, P > .05.

Collagenase-resistant implants exhibit a deficiency of endothelial cells but not other cell types.

WT or collagenase-resistant, r/r collagen at equal concentrations was copolymerized with buffer alone or bFGF/VEGF, prior to placement on the chick CAM. The embryos containing the collagen implants were incubated for 66 hours. Immunofluorescent detection of multiple cell types revealed a deficiency only of endothelial cells in collagenase-resistant (B,D,F) compared to WT (A,C,E) implants. Staining is shown for the endothelial cells with anti–von Willebrand factor (A,B), PMN heterophils with antichicken MMP-9 (C,D), or myofibroblasts with antismooth muscle actin (E,F). Bar indicates 50 μm. (G) Total cellularity was similar between collagenase-resistant and WT implants, as indicated by image analysis of total nuclear staining in the upper region of the implants. Data shown in bar graphs are the average of 5 independent samples ± SEM Mann-Whitney U test: n = 5, P > .05.

Discussion

Although a broad role has been established for the MMPs in angiogenesis, little direct evidence in vivo suggests that the cleavage of individual matrix components, such as collagen, is required during this process. Under experimental conditions in which a rapid, robust angiogenic effect was observed, we found that growth factor–induced vascularization was highly dependent on MMP activity. This dependence was indicated by the pronounced blockade of new vessel formation by both synthetic and natural inhibitors of MMPs. Several MMPs were detected in the implants and may contribute to the collagen remodeling that is required for angiogenesis. Furthermore, multiple cell types were identified in the newly vascularized collagen implants, raising the possibility that the MMPs necessary for blood vessel growth may derive from, or act through, a number of different nonendothelial cellular sources. Finally, our results suggests that cleavage at the specific triple-helical site of type I collagen must occur for the growth factor effect on blood vessel growth to be fully manifested. In the presence of a noncleavable collagen matrix, only endothelial cells, but not other cell types, were deficient in the implants. To our knowledge, growth factor–induced angiogenesis in vivo has not been shown previously to depend on such a specific matrix-remodeling event.

Because a multiplicity of pathways is thought to contribute to proteolytic remodeling during angiogenesis, a highly controlled in vivo model system of angiogenesis may be best suited to address the mechanism by which MMP inhibitors block blood vessel growth. Despite the fact that the chick embryo has been widely applied for studies of angiogenic stimulators and inhibitors, only recently was an assay developed25 that provides a relatively fast, quantitative measure of new blood vessel growth and eliminates the interpretive difficulties of assessing stimulatory or inhibitory effects on the preexisting vasculature within the CAM. We modified this assay system, which involves type I collagen polymerized around nylon meshes that are implanted on the CAM. Importantly, this system ensures that only newly formed blood vessels are quantitated, because the vessels are microscopically focused and scored only if they appear in the upper nylon mesh, a distance of 200 to 500 μm above the plane of the CAM with its dense, underlying network of preexisting vessels.

A histologic study of the engrafted collagen implants revealed that multiple cell types, in addition to endothelial cells, invaded the collagen during the incubation on the CAM. Perhaps not surprisingly, the cell types that were found have been previously implicated in angiogenesis in other contexts. A large number of myofibroblasts were observed; these represent the activated, contractile mesenchymal cells that are characteristic of dynamic tissues that are undergoing active remodeling.39 This population of cells may be important to the angiogenic milieu of the collagen implants because fibroblastic cells have been shown to be important sources of VEGF in angiogenic tissues in vivo.40 Two other cells types, macrophages and PMNs, both known to be intimately involved in angiogenesis, in part, through growth factor secretion,41,42 were also constituents of the collagen implants. It is not clear whether these cells appear coincident to the endothelial cells or whether they are major mediators of the angiogenesis we observe. Because a specific MMP activity (ie, cleavage of native collagen) appears to be necessary for angiogenesis, these infiltrating cells also may contribute to the enzymic content of angiogenic tissues, as macrophages, PMNs, and activated fibroblasts are well known producers of MMPs.43 44

A requirement for MMP activity in the induction of angiogenesis by bFGF and VEGF was demonstrated using 2 different types of MMP inhibitors: a synthetic, hydroxamate-based compound (BB3103) and TIMP-1, a natural MMP inhibitor. Based on the fact that both reagents are distinct but highly effective inhibitors of MMP activity27,45 and that natural inhibitors like the TIMPs have no known toxic or side effects, the most logical explanation for their similar inhibitory effects on angiogenesis is that they block MMP-mediated proteolysis. However, because BB-3103 and TIMP-1 can both block a broad range of MMPs,45 46 we cannot directly predict from these data which specific enzymes are the relevant targets in the observed inhibition of blood vessel growth. Selective inhibitors of individual MMPs are not yet available. Of note, we have detected in the implants both chicken MMP-2 and a chicken MMP-9–like enzyme that is associated with PMNs and at least 2 other MMPs, chicken MMP-13 and MMP-16. At least 3 of these 4 MMPs are candidates for the interstitial collagenolytic activity manifested in our angiogenesis system. We will be attempting to raise neutralizing (anticatalytic) antibodies specific to each of these enzymes, to test directly their functional role in angiogenesis. This will help circumvent the aforementioned lack of natural and synthetic MMP inhibitors that exclusively target individual MMPs.

An alternative approach to examining the role of MMP-mediated proteolysis in angiogenesis is to manipulate the enzyme substrate, as opposed to using enzyme inhibitors. Based on the substantial in vitro data in support of an important role for interstitial collagen in angiogenesis,47 we felt that type I collagen was an ideal candidate substrate to examine in vivo. Furthermore, a unique reagent, collagenase-resistant type I collagen, has been created and characterized22 that provides a means of testing whether the first cleavage in the extracellular degradation of type I collagen is essential for angiogenesis. Our results demonstrate that the full angiogenic effect cannot be manifested if this first proteolytic step is prevented.

The reduced vascularization of the implants composed of noncleavable collagen raises a number of provocative questions relating to the function of the triple-helical cleavage reaction and the more general dependence of angiogenesis on MMP activity. First, it remains an important issue whether “path clearing” is a major function of proteolysis during cell invasion in vivo.3 We did not observe a general decrease in total cellularity, however, between WT and r/r implants treated with growth factors (Figure 10). This suggests that cell invasion is not globally impaired by the presence of noncleavable collagen. Endothelial cells, however, were significantly reduced in r/r implants. Different cell types may exhibit varied proteolytic requirements for movement through extracellular matrix; keratinocytes, for example, have been shown to require the triple-helical cleavage for migration in vitro on a type I collagen matrix.48

Specific alterations to the extracellular matrix, such as the proteolytic cleavage of type I collagen and its subsequent unfolding, may also modulate both diffusible and matrix-associated cues to the invading endothelial cells and perhaps the supporting cell types. Evidence has been found that fragments of type I collagen are chemotactic for some of the cell types we identified.49,50The r/r collagen may generate only reduced levels of such fragments. The macromolecular structure of the collagen matrix may be crucial for delivering an orchestrated series of cues to cells, through direct activation of receptor tyrosine kinases51,52 and through integrin-mediated attachment and signaling.53-56 In fact, the presence of intact, fibrillar collagen versus denatured collagen significantly affects both of these pathways.51,52,57Therefore, balanced proteolysis of collagen may be of critical importance during cell invasion and vascular morphogenesis and may involve sequential attachment and loosening of matrix contacts in a directional manner,48 with appropriate signals being generated at each step. The r/r collagen would not undergo such balanced proteolysis.

Although basement membrane degradation has been postulated as a major function of MMPs during angiogenesis in vivo,36 our results suggests that specific proteolysis of interstitial collagen may also be a rate-limiting step. Future studies to address the role of MMPs in angiogenesis may be well served by accounting quantitatively not only for the enzyme but also the substrate. Such a complementary approach may yield more precise targets in the development of antiangiogenic agents.

We thank Drs Stephen M. Krane and Michael H. Byrne (Massachusetts General Hospital) for generously providing mouse collagens, Dr Steven R. Van Doren (University of Missouri) for N-TIMP-1, Dr Judith Abraham (Scios) for bFGF, and Dr Anne Eichmann (CNRS) for antibody 5H6. We also thank Wen-Hui Feng (UMIC, SUNY at Stony Brook) for her superb cryostat work.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA55852 and HL31950 (J.P.Q.), training grants T32-HL07195 (R.T.A.) and T32-HL07695 (D.Z.). The work also represents part of the doctoral thesis dissertation of M.S. conducted under the Molecular and Cellular Biology Graduate Program of SUNY at Stony Brook.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

James P. Quigley, Department of Vascular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 N Torrey Pines Rd/VB1, La Jolla, CA 92037; e-mail: jquigley@scripps.edu.