Abstract

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is characterized by the massive infiltration of secondary lymphoid organs with activated CD8+ T lymphocytes. While converging data indicated that these cells were HIV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) responsible for HIV spread limitation, direct evidence was lacking. Here, the presence of HIV-specific effector CTLs was demonstrated directly ex vivo in 15 of 24 microdissected splenic white pulps from an untreated patient and in 1 of 24 tonsil germinal centers from a second patient with incomplete viral suppression following bitherapy. These patients had plasma HIV RNA loads of 5900 and 820 copies per milliliter. The frequencies of HIV-1 DNA+ cells in their lymphoid organs were more than 1 in 50 and 1 in 175, respectively. Spliced viral messenger RNA (a marker for ongoing viral replication) was present in most immunocompetent structures tested. Conversely, CTL activity was not found in spleens from 2 patients under highly active antiretroviral therapy, with undetectable plasma viral load. These patients had much lower spleen DNA+ cell frequencies (1 in 2700 and 1 in 3800) and no white pulps containing spliced RNA. CTL effector activity as well as spliced viral messenger RNA were both concentrated in the white pulps and germinal centers. This colocalization indicates that viral replication in immunocompetent structures of secondary lymphoid organs triggers anti-HIV effector CTLs to these particular locations, providing clues to target therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

During the chronic phase of infection, antigenic stimulation drives human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) replication in vivo.1,2 Accordingly, HIV replication is mainly restricted to secondary lymphoid organs, which are the major sites of primary and secondary immune responses.3-11 Lymph nodes and tonsils have an organized structure with primary follicles, germinal centers (or secondary follicles) generated in response to antigens, surrounded by T-cell areas. The spleen is the major secondary lymphoid organ for the defense against bloodborne pathogens. It is divided into red pulp and white pulps. The latter comprises periarteriolar lymphoid sheaths—made of T lymphocytes and dendritic cells—and B-cell areas (primary follicles and germinal centers) that contain B lymphocytes, follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, and dendritic cells. Among these, the CD4+T-lymphocyte population contains the majority of HIV-infected cells in the lymphoid organ.12,13 Dendritic cells and macrophages are much less frequently infected,13 while FDCs are not productively infected by HIV but retain large amounts of virions at their surface.5,7,14 15

Sequencing of HIV from individual white pulps suggested bursts of local viral replication, but analysis of the viral quasi species showed that viral replication was strongly restricted.16-19The best candidates to limit viral spread are the HIV–specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Indeed, these cells are found in large numbers in clinical samples from infected patients18,20 and inhibit HIV replication in vitro21 by different mechanisms: direct lysis of infected cells or inhibition of viral replication by interleukin or chemokine secretion.22 After peaking at high levels during primary infection, the viral load decreases at a time when CTL responses are high, while HIV-specific antibodies are usually undetectable.23-26 The viral load then reaches a set point, which is predictive of the clinical outcome.27 In this context, some CTL responses were correlated with decreased viral loads and with a better prognosis.27-30 More recently, CD8+ T-cell depletion in simian immunodefiency virus (SIV)–infected macaques was shown to lead to an immediate rise of the viral load, further confirming the role of CD8+ T lymphocytes in limiting disease progression.31-33

At the site of HIV replication, ie, lymphoid organs, massive infiltration of clonally expanded CD8+ T cells is observed.17,34,35 These lymphocytes contain TiA1+ granules, indicating their cytotoxic effector potential, and have a memory phenotype, especially in the germinal centers.35 Individual white pulps from HIV patients were found to have a discrete distribution of T-cell clones characterized by their rearranged T-cell receptor β chain.17 Some of these sequences were found in most of the white pulps from a patient as well as in HIV-specific CTL lines derived from bulk spleen mononuclear cells (SMCs). This suggested indirectly the infiltration of individual white pulps by HIV-specific CTLs. In the present work, individual hyperplastic white pulps or germinal centers from spleens or tonsils were microdissected, and their cells assayed for CTL activity ex vivo just after surgery for therapeutic purposes. Data provide direct evidence of HIV-specific CTL activity in individual immunocompetent structures of secondary lymphoid organs. In parallel, viral spliced messenger RNA (mRNA) was polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–amplified to check whether HIV-producing cells colocalized in these structures with anti-HIV CTLs.

Materials and methods

Clinical specimens

Patients underwent surgery for the treatment of the clinical syndromes indicated in Table 1, and their spleens and tonsils were used according to the national ethical guidelines. Normal lymphoid organs were obtained from organ transplant donors at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital following national ethical guidelines. Lymphoid organs were immediately cut into small pieces and transported on ice in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Cergy-Pontoise, France). On the one hand, bulk mononuclear cells were obtained by mechanical and mild enzymatic dissociation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 20 U/mL collagenase VII (Sigma, St Quentin Fallavier, France) and 40 U/mL DNase I (Sigma) in 2% fetal calf serum for 30 minutes at room temperature, addition of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid to 10 mM and agitation for 5 minutes, and then separation by centrifugation over diatrizoate-Ficoll (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) as described.13 On the other hand, white pulps or germinal centers were dissected under a stereomicroscope (magnification 10 ×). Cell suspensions from these structures were then made by incubation in PBS containing collagenase VII and deoxyribonuclease (DNase) for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by mechanical dissociation by repeated pipetting through 1 mL Eppendorf pipette tips. A few days to several weeks before surgery, HLA typing was performed using a standard complement microcytotoxicity assay (Dr I. Theodorou, Laboratoire d'Immunologie cellulaire et tissulaire, Hôpital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France).

Chromium release test

Cytotoxicity was assessed using a 4-hour chromium release assay.17 Target cells were autologous or HLA-matched heterologous B-lymphoblastoid cell lines. They were infected with a mixture of recombinant vaccinia viruses, each at a multiplicity of infection of 5 plaque-forming units per cell, expressing cytoplasmic glycoprotein160, reverse transcriptase (RT), or gag of HIV-1 Lai (No. 3183, 4163, or 1144, respectively; Transgene, Strasbourg, France) for 18 hours before the assay. Control targets were infected with wild-type Copenhagen vaccinia virus (15 plaque-forming units per cell). Targets were then washed, incubated with 300 μCi (11 000 MBq) Na251CrO4 in 100 μL fetal calf serum (Amersham, Les Ulis, France) for 1 hour, and washed 3 times. Targets were added at 1000 cells per well to serial dilutions of cells from the white pulps or germinal centers in triplicate. Unlabeled targets infected with wild-type vaccinia virus were added to the assays (10 000 cells per well) to decrease the background. In some experiments, anticlass I major histocompatibility class (MHC) molecule monoclonal antibody w6/32, kindly given by Dr Pierre Langlade, Institut Pasteur, Paris, was added to the targets for 30 minutes before adding to the effectors, and during the assay, at a final dilution of 1:50. After 4 hours culture in 5% CO2 at 37°C, 50 μL of the supernatants was collected in Lumaplate 96 solid scintillation plates (Beckman, Groningen, Netherlands), and 10 μL of chlorine diluted 1:2 was added to inactivate the virus before drying and counting on a Microbeta counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). The percent specific release was calculated as follows: 100 × (test cpm − minimal release)/(maximal release − minimal release). Maximal and minimal chromium release were assessed in sextuplicate wells where chlorine or culture medium were added to the targets, respectively. The specific release of gag-pol-env–expressing targets was considered positive when it was more than 10% above the release of control targets for at least 2 consecutive effector:target ratios and showed a positive correlation with the effector:target ratio.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis of surface markers was done on cell suspensions. Immunostaining was performed using anti-CD3 (SK7) peridinin chlorophyll protein, anti-CD4 (SK3) fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC), anti-CD8 (Leu-2a) phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD25 (2A3) FITC, anti-CD38 (HB7) PE, anti–HLA-DR (L243) FITC (Becton Dickinson, Pont-de Claix, France), anti-CD19 (J4119) PC5, anti-CD45RA (ALB11) FITC, anti-CD45RO (UCHL1) FITC, and TiA1 (2G9) PE (Immunotech, Marseille, France), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For intracellular TiA1 staining, the cells were washed in PBS–bovine serum albumin 0.1% saponine and incubated with TiA1 for 20 minutes. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur instrument and analyzed with the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson).

Nucleic acid analysis

Total RNA and DNA were extracted from individual white pulps or germinal centers or cell pellets using Master Pure extraction kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI). Briefly, 2 μg transfer RNA (Sigma) was added to each sample as carrier, cells were lysed in the presence of proteinase K for 15 minutes, and the cell lysate was then split to purify either RNA or DNA according to the manufacturer's procedure. On each extract, several PCR amplifications were performed to detect proviruses, full-length viral RNA, and spliced RNA. To avoid contaminations, the reverse transcriptase (RT) and PCR steps of the amplifications were performed in one tube. LV13 oligonucleotide was used as primer for complementary DNA synthesis.16 For unspliced RNA and DNA, LV13 and LV15 primers were used in the first cycle while SK122/123 16 served as nested primers. Negative controls without RT were performed. For spliced RNA amplification, LV15 primer was replaced by LTR-SD: TCTCTCGACGCAGGACTCGGCTTG. Positive controls of DNA and RNA amplification were performed using the following CD3 gene-specific primers: first cycle, for DNA, CD3A: GCCTGGCTGTCCTCATCCTGGCTATC and CD3B: TGGCCTATGCCCTTTTGGGCTGCATTC,1 for RNA, CD3OUT5: GACATGGAACAGGGGAAGGG and CD3OUT3: GAGAAAGCCAGATATGGTGG; nested cycle, for both DNA and RNA, CD3IN5: CTTCTTCAAGGTACTTTGG and CD3IN3: ACTTCTGTAATACACTTGGAGTGG. The frequency of HIV DNA-containing cells was determined by limiting-dilution nested PCR as described,13 16 using noninfected B-lymphoblastoid cells as carriers.

Results

Phenotypic analysis of patient lymphoid organ bulk cell populations

Spleens from 3 patients and tonsils from 1 patient who underwent surgery for therapeutic reasons were collected (Table 1). The different populations present in bulk mononuclear cells from these lymphoid organs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Infiltration by CD3+CD8+ cells was found in untreated (patient B) and treated (patients C and R) HIV+ patient spleens, with a concomitant decrease in the proportion of B lymphocytes compared with normal organ donors (Table 2). In these 3 patients (Table 2), conversely to others (data not shown), the proportion of CD4+ T lymphocytes was not decreased when compared with controls. Patient R had the most important CD8+ T-cell infiltration, with signs of activation (elevated CD38 expression) in a significant proportion of these cells. However, in these bulk spleen cells, none of the patients had an elevated proportion of CD25, the interleukin-2 receptor α chain, a T-cell activation marker, and the high proportion of cells bearing TiA1, a marker of cytotoxic granules, was rather low compared with that observed in normal spleens. In parallel, phenotypic analysis was performed on a few microdissected splenic white pulps from patient B. About 23% to 32% of the cells from these white pulps were CD8+, most being CD45RO+, HLA-DR+(data not shown). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis could not be performed on microdissected structures from all of the patients, but these data indicate that phenotypic analysis of total splenocytes does not reflect the individual splenic white pulp populations.

Direct HIV-specific CTL effector activity in microdissected white pulps or germinal centers

Hyperplastic white pulps or germinal centers were microdissected from the spleen or the tonsil of the HIV+ patients. The cells were extracted by mechanical disruption and collagenase-DNase treatment (as in “Materials and methods”). From these structures, 0.02 × 106 to 4.1 × 106leukocytes were isolated (Table 1), which was enough to perform cytotoxicity assays. Target cells consisted of autologous or partly HLA-matched Epstein-Barr virus–transformed B-cell lines, because HLA typing of the patients was obtained before splenectomy. Due to the limited number of effector cells, CTL activity was tested on targets infected with a mixture of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gag, RT, or glycoprotein 160 genes of HIV-1 Lai. Control targets were infected with wild-type vaccinia virus.

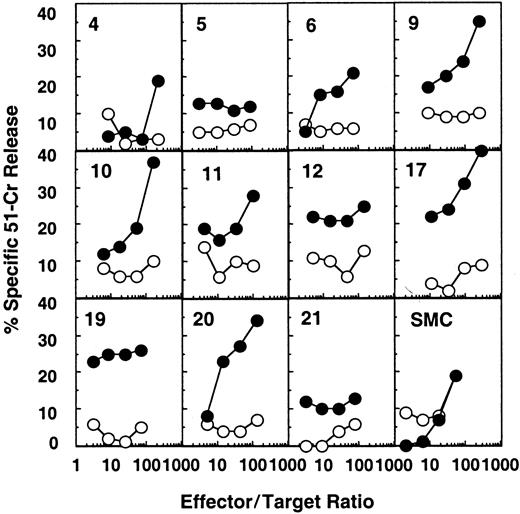

HIV-1–specific cytotoxic activity was detected ex vivo in most splenic white pulps from patient B, who was not receiving antiretroviral treatment and had a plasma viral load of 5900 copies per milliliter (Figure 1 and Table 1). Fifteen of 24 white pulps showed an HIV-specific cytotoxicity at more than one effector:target ratio (white pulps 2, 3, 6, 9-13, 17-20, 22-24, Figure1, Table 3, and not shown). Moreover, in some of these CTL-containing white pulps (ie, white pulps 2, 12, 18, 19, 22), the chromium release remained significantly positive (more than 10% of anti-HIV–specific lysis) even at an effector:target ratio of 10:1 or less, suggesting a high frequency of anti-HIV–specific CTLs in these structures.

Detection of HIV-specific CTL effectors ex vivo from individual white pulps from the spleen of patient B.

Target cells were autologous B-lymphoblastoid cells infected with either a mixture of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gag, pol, or env (●) or wild-type vaccinia (○). Results from 11 representative white pulps of the 24 tested and from bulk SMCs are shown.

Detection of HIV-specific CTL effectors ex vivo from individual white pulps from the spleen of patient B.

Target cells were autologous B-lymphoblastoid cells infected with either a mixture of recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gag, pol, or env (●) or wild-type vaccinia (○). Results from 11 representative white pulps of the 24 tested and from bulk SMCs are shown.

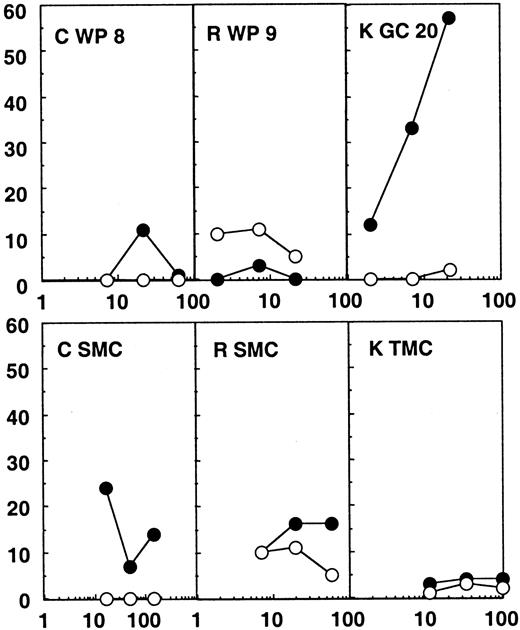

Twenty-four white pulps, microdissected from the spleen of patients C and R, were tested for CTL activity. These patients were efficiently treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), their plasma viral load being under the detection limit (Table 1). No CTL activity was found directly ex vivo from these structures (Figure2). A direct CTL activity was also detected in one tonsilar germinal center of 24 tested from patient K, who was treated with zidovudine (AZT) and didanosine (ddI) only and showed incomplete viral suppression and a plasma viral load of 820 copies per milliliter. In this particular germinal center (Figure 2), a 57% specific chromium release was obtained at an effector:target ratio of 22:1 against the HIV expressing targets, while wild-type infected targets were not recognized. MHC class I restriction could be demonstrated by blocking the CTL activity with anticlass I monoclonal antibodies (data not shown).

Chromium release assays from the lymphoid organs of patients C, R, and K.

Results from the bulk SMCs or TMCs and from one white pulp (WP) or germinal center (GC) of the 24 tested for each patient are shown. Partially compatible B-lymphoblastoid cell lines were infected with wild-type vaccinia (wt; ○) or recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gag, pol, and env (●) and used as targets. The HLA molecules shared between patient and target cells are shown in Table 1.

Chromium release assays from the lymphoid organs of patients C, R, and K.

Results from the bulk SMCs or TMCs and from one white pulp (WP) or germinal center (GC) of the 24 tested for each patient are shown. Partially compatible B-lymphoblastoid cell lines were infected with wild-type vaccinia (wt; ○) or recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing gag, pol, and env (●) and used as targets. The HLA molecules shared between patient and target cells are shown in Table 1.

Notably, no CTL activity was detected in bulk spleen or tonsil mononuclear cells in any of the patients (SMCs or TMCs, Figures 1 and2). Therefore, the CTL activity found in some of the immunocompetent structures was much higher than the global CTL activity found in the lymphoid organs. These results point to a concentration of anti-HIV–specific CTLs in many splenic white pulps from the untreated patient and in one of the germinal centers analyzed from the patient under AZT and ddI treatment, while in the patients under efficient triple therapy no CTL activity was detectable in the immunocompetent structures of the spleen.

Proviral DNA and HIV replication

HIV nucleic acids were detected in bulk mononuclear cells either by limiting dilution or in fixed number cell extracts and were detected in cells from individual white pulps or germinal centers. PCR allows detection of HIV-1 proviral DNA, while RT-PCR shows the presence of either unspliced RNA, which mostly represents virions trapped on FDCs in the germinal centers, or spliced RNA, which detects viral transcription.

HIV infiltration was analyzed by limiting-dilution PCR13 16 on bulk lymphoid organ cells isolated from the 4 patients. As shown in Table 4, the frequency of infected cells was 1 to 2 logs higher in the 2 patients with a detectable plasma viral load (patients B and K, > 1:50 and 1:175, respectively) than in the 2 others (patients C and R, 1:2700 and 1:3800, respectively). When analyzed in extracts from 2 × 105 splenic or tonsillar bulk mononuclear cells, proviral DNA and viral RNA were found in the lymphoid organs from the 4 patients irrespective of their plasma viral load; conversely, spliced RNA was not detected, indicating low levels of replication in all 4 patients (Table 4, bulk cells).

The presence of HIV RNA (spliced and unspliced) was analyzed in the white pulps of patient B tested for anti-HIV CTL activity (most of the cells were used for the CTL assay, and the remaining cells, ie, 6% of each white pulp, were tested by PCR and RT-PCR). Genomic (unspliced) RNA was detected in all 16 samples analyzed (Table3). Moreover, 5 of the white pulps showed evidence of ongoing viral replication, as determined by the amplification of spliced viral mRNA (ie, white pulps 4, 10, 11, 12, and 19). Of these 5 white pulps, 4 contained effector anti-HIV CTLs (Table3 and Figure 1).

Because the number of cells remaining for PCR after the CTL assay was limited, HIV-DNA was amplified from 5, 9, and 8 total white pulps from patients B, C, and R, respectively, as well as from 9 germinal centers from patient K's tonsil (Table 4). All the samples were positive except for 2 of 9 white pulps from patient C (Table 4), confirming the presence of HIV-infected cells in most of the immunocompetent structures of the secondary lymphoid organs.

The same white pulps or germinal centers were also screened for the presence of viral RNA and intracellular spliced mRNA. HIV-1 RNA was found in 5 of 5 white pulps from patient B, consistent with bulk cell data. Spliced RNA was found in 4 of 5 white pulps from this patient, in contrast to the negative result obtained with bulk cells (Table 4). Similar results were obtained for patient K (2 of 2 germinal centers contained both full-length and spliced viral RNA). However, in treated patients, while all the white pulps did contain HIV infected cells, no evidence of sustained viral replication was observed (Table 4, 0 of 4 and 0 of 5 positive white pulps for spliced RNA).

These data show that the frequency of cells bearing HIV proviral DNA was consistent with the level of plasma viremia. Moreover, cells containing replicating virus (spliced RNA) were found, as well as anti-HIV CTLs, concentrated in the white pulps or germinal centers of patients with detectable viremia. Patients under effective triple therapy showed neither CTL infiltration nor viral replication within their white pulps, consistent with an efficient control of viral replication.

Discussion

In this report, direct evidence of the HIV-specific lytic function of the CD8+ lymphocytes infiltrating single white pulps or germinal centers from infected patients is presented for the first time. Moreover, these cells were shown to colocalize with productively HIV-infected cells in the immunocompetent structures of secondary lymphoid organs. This had been suggested, but not demonstrated, by previous data using T-cell receptor sequence analysis in splenic white pulps or in situ observation of CD8+CD45RO+TiA+ cells in lymph node germinal centers.17,35 HIV-specific memory CTLs have been found in bulk spleen cells from infected patients,36 and SIV-specific memory CTLs have recently been observed in lymph nodes from experimentally infected macaques.37 However, their localization in the white pulps or germinal centers, where most of the viral replication takes place,12,35 was not studied. In another report, HIV epitope–specific CTLs expanded in vitro and genetically modified were reinfused in patients and were shown to migrate to the lymph nodes, adjacent to productively infected cells, in the parafollicular regions.38 These regions are contained in the immunocompetent structures that were microdissected in the present work. Here, the CTL activity was concentrated in the white pulps or germinal centers, because it was below detection levels in bulk mononuclear cells isolated from the same lymphoid organs. The presence of viral DNA or RNA was analyzed at the level of individual white pulps or germinal centers. Proviral DNA was detected in the tested white pulps from patients B and R, most of those from patient C, and all germinal centers tested from patient K, in accordance with previous results obtained in spleens or lymph nodes.11,16,17,35 Unspliced RNA was found in all of the immunocompetent structures from the 2 patients with detectable plasma viral loads, while it was rarely detected in the 2 other patients. Unspliced RNA is a sign that the white pulps were, or had been, the sites of viral replication. Indeed, most viral unspliced RNA represent viral particles retained on the FDC surfaces.15 Viral particles in splenic white pulps from patients B and K seemed more widespread than in the lymph node germinal centers from asymptomatic patients studied previously by in situ hybridization, who had detectable virus in only 15% to 30% of their germinal centers.35 However, the nested RT-PCR used here is much more sensitive than in situ hybridization, because it can detect as little as one infected cell.

While all the white pulps analyzed from patient B contained viral particles (Table 3), only 15 of 24 displayed HIV-specific CTL activity. The presence of HIV-producing cells was analyzed by PCR amplifying spliced viral mRNA in some of the pulps. It was detected in only 4 of 10 CTL+ white pulps. However, only a small fraction (about 6%) of each white pulp was available for PCR analysis after using cells for the CTL assay. Spliced RNA was thus analyzed in 5 total white pulps from patient B. Viral replication was detected in 4 of 5 white pulps, whereas it was undetectable in bulk lymphoid organ cells, suggesting that most of the immunocompetent structures of this spleen are the site of active viral replication despite the absence of detectable CTL activity in 9 of 24 pulps tested. This discrepancy between the detection of viral replication and CTL activity may have several explanations. First, the sensitivity of the chromium release assay is limited. Detection using MHC-peptide tetramers is more sensitive and has allowed finding SIV gag-specific CTLs in macaques and reinfused HIV-specific clones in patient secondary lymphoid organs.37,38 However, in natural HIV infection analyzed here, a dominant, highly represented CTL response directed against the single epitope presented in the tetramers may not be present at the very time of splenectomy. Lysis of target cells infected with 3 different recombinant viruses, expressing 3 widely recognized proteins, is expected to be more consistent. Moreover, T cells binding MHC-peptide tetramers can be nonfunctional.39,40 Second, the epitopes presented by the targets may be different from the variant epitopes presented by the cells of the patient. This might formally also be a possibility for the absence of effector CTL detection in the 2 HAART-treated patients, ie, mutants induced by therapy; however, 3 different whole proteins containing multiple epitopes were tested, and after stimulation in culture anti-HIV memory CTLs were detectable on the same target cells. Third, and more importantly, it is possible that some of the white pulps analyzed here contained recently developed germinal centers, where HIV replication, which mostly occurs in antigen-stimulated T cells, was identified by RT-PCR but still too weak to induce a CTL infiltration detectable using a chromium release assay.1,41 Indeed, HIV enters the immunocompetent structures of secondary lymphoid organs in the form of integrated proviral DNA in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Antigen-specific stimulation of these latently infected cells is necessary to initiate viral replication and HIV protein production.1 This in turn induces HLA class I–restricted HIV peptide presentation at the surface of infected cells, a prerequisite to local CTL infiltration and stimulation. Fourth, in immunocompetent structures analyzed totally for the presence of nucleic acid, without diverting most of the cells for a CTL assay, the presence of spliced RNA was consistent with the plasma viral load, the frequency of DNA-positive cells in the bulk cells, and the detection of CTLs directly ex vivo.

The detection of HIV-specific effector CTLs ex vivo in the white pulps and germinal centers from 2 patients is consistent with the detection of viral RNA in their plasma and with that of spliced RNA (replicating virus) in most of the immunocompetent structures of their secondary lymphoid organs. These patients were not treated by HAART at the time of surgery. Conversely, the 2 patients who had no detectable CTLs in their lymphoid organs had undetectable plasma viral loads as a result of HAART. Viral RNA (ie, viral particles) and proviral DNA were still detectable in their lymphoid organs, as reported for other patients42,43; however, if viral RNA was present in bulk SMCs, no evidence of viral replication was observed in the microdissected white pulps from these patients. It has been shown that several months after plasma viremia becomes undetectable under HAART, virions can still be detected by in situ hybridization on lymph node FDCs.35,44 A better correlation between plasma and lymphoid organ viral load is found when plasma RNA detection thresholds are lower (< 20 copies/mL) than in the tests used here45or when the frequency of infected cells in the lymphoid organs is measured.46 Here, the frequencies of HIV DNA+cells in the lymphoid organs were 1 to 2 logs lower in the patients treated with HAART than in the other patients with detectable plasma viral loads. Therefore, HAART resulted in undetectable plasma viremia, a decrease in lymphoid organ viral load, and a disappearance of local cytotoxic activity. Similar conclusions on the disappearance of CTL activity have been made in peripheral blood.29,30,39,47-49However, in lymph node germinal centers and in tonsils, increased numbers of CD8+ T cells were still found 3 months after viral replication was controlled in HIV-infected patients.35 50 Here CD8+ T cell infiltration was observed in the lymphoid organs from the 4 patients, but the effector function was no longer present when viral load, hence antigen production, was reduced by HAART.

In peripheral blood, CTL activity disappears shortly after viral load (ie, HIV antigens) is reduced to undetectable levels by HAART30,39,47 and is absent in some long-term nonprogressors harboring defective virus51: Chronic antigen stimulation is necessary for sustained effector CTL activity. This is probably also true at the microanatomic level in the white pulps and germinal centers.

In contrast to the activity usually observed after in vitro culture, the direct CTL activity in fresh individual white pulps or germinal centers represents in vivo clonally expanded activated CTLs responding to local HIV antigen production. Indeed, even if they were not systematically found in the same white pulps, CTL effectors and replicating virus were concentrated in these structures. Analysis of quasi species shows that HIV replicates locally in individual white pulps, but this replication is strongly limited19b(M. J. Dumaurier et al, unpublished data, June 2000). The data presented here confirm the major role of HIV-specific CTL effectors in this strong restriction of viral spread in vivo and can provide clues to target therapeutic intervention.

We thank Pr Jean-Pierre Clauvel and Jean-Gérard Guiller for support, Drs Valérie Pézo, Jean-François Desoutter, and Guislaine Carcelain for help, Dr Marie Paule Kieny from Transgene for vaccinia viruses, Dr Ioannis Theodorou and his team for HLA typing, Dr Pierre Langlade for w6/32 antibody, Drs Mireille Viguier and Marc Dalod for reading the manuscript, and Dr Rafick P. Sekaly for helpful discussion.

Supported by grants from the Institut Pasteur, the Agence Nationale de la Recherche contre le SIDA (ANRS), and Sidaction/Ensemble contre le SIDA (A.S.). M.J.D. was supported by an ANRS fellowship.

A.S. and M.-J.D. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Anne Hosmalin, Unité INSERM 445, Institut Cochin de Génétique Moléculaire, Bâtiment Gustave Roussy, 27 rue du Faubourg St Jacques, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: hosmalin@cochin.inserm.fr.