Abstract

The CD95 receptor, a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, mediates signals for cell death on specific ligand or antibody engagement. It was hypothesized that interferon α (IFN-α) induces apoptosis through activation of the CD95-mediated pathway and that CD95 and ligands of the death domain may belong to the group of IFN-stimulated genes. Therefore, the effect of IFN-α on CD95-CD95L expression, on the release of TNF-α, and on TNF receptor 1 expression in an IFN-sensitive human Burkitt lymphoma cell line (Daudi) was investigated. After 5 days' incubation, apoptosis in 81% of IFN-α–treated Daudi cells was preceded by a release of TNF-α and an induction of CD95 receptor expression. Although supernatants of IFN-treated Daudi cells induced apoptosis of CD95-sensitive Jurkat cells, CD95L was undetectable on protein or on messenger RNA levels, and the weak initial expression of TNF receptor 1 increased only slightly during IFN treatment. Surprisingly, binding of TNF-α to CD95 was observed and confirmed by 3 different techniques—enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using immobilized CD95:Fc–immunoglobulin G, immunoprecipitation assay using CD95 receptor precipitates of Daudi cells, and binding of sodium iodide 125–TNF-α to Daudi cells, which was strongly stimulated by IFN-α and inhibited by CD95L, CD95:Fc, unlabeled TNF-α, and anti–TNF-α antibody. Preincubation of Daudi cells with antagonists of the CD95-mediated pathway resulted in an inhibition of IFN-α–mediated cell death. The present investigation shows that IFN-α induces autocrine cell suicide of Daudi cells by a cross-talk between the CD95 receptor and TNF-α. The CD95 receptor can be considered a third TNF receptor, in addition to p55 and p75.

Introduction

Numerous investigations have shown that growth inhibition and apoptosis are regulated by various oncogens and tumor suppressor genes.1 The bcl-2 proto-oncogene product is one of the most efficient inhibitors of apoptosis in different cell types.2 By analogy, 2 members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily, TNF receptor type 1 (p55) and APO-1/Fas (CD95), can be considered proapoptotic tumor suppressor genes that lead to cell death3-5 after activation by their ligands.6,7 In a similar way, these ligands (TNF and APO-1/Fas-ligand [CD95L]) represent related type 2 membrane glycoproteins. Defects in CD95-mediated cell death may be responsible for some auto-immune diseases and may play a role in ontogeny.8

An interaction of immunomodulating compounds with receptors and ligands of the death domain seem to be of high value in cancer treatment. Interferons (IFNs), the most prominent group of immunomodulating compounds, exert their pleiotropic biologic activities by the modulation of gene expression. Examples of well-characterized IFN-modulated genes and gene products are the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens and the c-myc and retinoblastoma genes.9-12 Enhancement of MHC antigens has been considered important in T-lymphocyte–mediated cytotoxicity.13IFN-α down-regulates the expression of c-myc and up-regulates the retinoblastoma gene in a Burkitt lymphoma cell line (Daudi), and it has been assumed that these genes are closely involved in IFN-induced growth inhibition.14-16 Recently, IFNs have been shown to enhance CD95 expression and to induce apoptosis in various cell systems. However, the activation of ligands of the death domain could not be observed in these experiments.17 18

IFN-α exerts antitumor activity in several types of neoplasm, including chronic myeloid leukemia,19 Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative disorder, hairy cell leukemia, and some solid tumors.20-23 The molecular mechanisms that lead to tumor regression during IFN treatment are not fully elucidated. We hypothesized that CD95 and ligands of the death domain may belong to the group of IFN-stimulated genes and that IFN-α might induce apoptosis through an up-regulation of receptors and ligands of the death domain. In the present study, we investigated whether the CD95 receptor/ligand system is involved in IFN-induced cell death and whether the CD95 receptor might be activated by cross-reactivity with TNF-α.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and IFN

IFN-sensitive Daudi cells were grown between 1 and 5 days in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL/Life Technologies, Paisley, United Kingdom) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco BRL). In addition, cells were incubated for up to 5 days in RPMI 1640 + 10% FCS containing 200 U/mL recombinant (rec) human IFN-α2a (Roferon-A; Hoffmann La Roche, Basel, Switzerland). IFN-resistant Daudi cells and the lymphoblastoid cell line Raji served as controls in the supernatant cytotoxicity assay and were grown under the same conditions. Cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD).

Cell growth, viability, and morphology

Cell growth was measured by counting cell numbers in a Bürker Türk hemocytometer (Assistent, Sondheim-Rhön, Germany). Cell viability was assessed by the trypan blue exclusion test. Counts were performed in triplicate. Cell morphology was evaluated by May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained cytocentrifuge cell preparations. Cells were evaluated as apoptotic according to the criteria introduced by Kerr et al,24 which included compaction of the nuclear chromatin, fragmentation of nuclei, condensation of the cytoplasm, and separation of the cell into apoptotic bodies.

Immunofluorescence analysis, monoclonal antibodies, and reagents

Purified antibodies.

Antihuman CD95L (clone NOK-1) was purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Antihuman TNF receptor p55 (clone MR 1-2) was obtained from Monosan (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Purified and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)–negative control antibodies and phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin were obtained from DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark). FITC-labeled antihuman CD95 (clone UB2) was obtained from Oncor (Gaithersburg, MD). The metalloproteinase inhibitor KB-R8301 was kindly provided by Kanebo Pharmaceuticals Research Center (Osaka, Japan).

Immunofluorescence labeling.

Cells (2 × 106) were incubated with suitable dilutions of unlabeled antihuman CD95L, antihuman TNF receptor p55, and appropriate control antibodies according to the manufacturers' instructions. For CD95L labeling, cells were pretreated with 10 μM metalloproteinase inhibitor KB-R8301.25 After 2 washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 2% FCS, secondary staining was performed with FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat antimouse Ig (An der Grub, Kaumberg, Austria). After they were washed, cells were analyzed on a Facscan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Detection of DNA strand breaks by TdT assay.

Quantification of apoptosis was performed by detection of DNA strand breaks using the TdT assay.26 Briefly, 2 × 106 cells were washed twice in PBS supplemented with 2% FCS and incubated with FITC-labeled antihuman CD95 (UB2) antibody or with FITC-conjugated mouse control antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature. After that, they were washed twice and fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS. Staining was performed by incubating the cells for 1 hour at 37°C with 0.5 nM biotinylated dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) and 100 U/mL terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Boehringer Mannheim) in appropriate buffer (0.2 M potassium cacodylate, 25 mM Tris-HCl, 2.5 mM CoCl2, and 0.25 mg/mL bovine serum albumin). Cells were then washed twice in PBS and resuspended in 100 μL 4 × saline sodium citrate buffer containing 2.5 μg/mL phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin. After 2 washes, cells were resuspended in 1 mL PBS. Cells exposed to the buffer but incubated without TdT-enzyme served as negative controls. Data were analyzed by the Facscan (Becton Dickinson) as before.

Caspase-3 assay.

Daudi cells were cultured in medium as before, without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α, for 5 minutes to 72 hours. Cells were then harvested, and the lysates were analyzed by a commercial caspase-3 (CPP32) Assay Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were read in a spectrophotometer at 405 nm.

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of RNA transcripts.

Daudi cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IFN-α (200 U/mL) for 4 hours, 20 hours, and 48 hours. As a control, Jurkat cells were cultured in the presence or absence of 5 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibody (Ancell, Bayport, MN) for 4 hours. At the indicated time points, cells were harvested and washed once with PBS. Total RNA was prepared using the RNAzol method, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Single-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg RNA in a 20-μL reaction mixture containing pd(N)6 random hexamer primers (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and 200 U Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (RT; Gibco BRL). Aliquots of 5μL cDNA were amplified in a Gene Amp PCR Thermal Cycler (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA) with 2.5 U Amplitaq DNA Polymerase (Perkin Elmer) diluted in the buffer supplied by the manufacturer and 50 pmol of forward and reverse oligonucleotides. Primers had the following sequences: CD95L (forward, 5′-GGGTCGACGGGATGTTTCAGCTCTTCCACCTAC-3′; reverse, 5′-GCTCTAGAACATTCCTCGGTGCCTGTAAC-3′); β-actin (forward, 5′-AGGCCGGCTTCGCGGGCGAC-3′; reverse, 5′-CTCGGGAGCCACACGCAGCTC-3′). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Supernatant cytotoxicity assay.

For the detection of CD95-induced killing, chromium 51 (51Cr)–labeled Jurkat cells were incubated with supernatants of IFN-α–treated Daudi and Raji cells. Jurkat cells were labeled with 51Cr (100 μCi) for 1 hour at 37°C, then washed and seeded (1 × 104 target cells) in the presence of 1 mL various supernatants. After 2 days of incubation at 37°C, 51Cr in supernatants was determined using a gamma counter. Percentage specific 51Cr release was calculated according to the formula: 100 × [(experimental cpm) − (spontaneous cpm)]/[(maximum cpm)−(spontaneous cpm)], where spontaneous cpm is the cpm of target cells incubated in media only and maximum cpm is cpm released in the presence of 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). For the blocking experiment, Jurkat cells (1 × 104 cells/mL) were cultured with supernatants of IFN-treated Daudi cells in the absence or presence of 100 ng/mL anti–TNF-α antibody (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Culture supernatants of Daudi cells were collected from day 1 to day 5 after incubation without or with IFN-α (200 U/mL). Supernatants were tested by commercial kits for soluble CD95L (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) and TNF-α (R&D Systems).

Competition experiments were performed using coated 96-well plates (Merck, Vienna, Austria). RecCD95:Fc-IgG (Alexis, San Diego, CA) or antihuman CD95L antibody (clone NOK-1) was bound to the plates using an anti-IgG:Fc undercoat (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Simultaneous competition was achieved by incubation of biotinylated TNF-α (R&D Systems) with either unlabeled recTNF-α (kindly provided by Boehringer Ingelheim, Vienna, Austria) or unlabeled recCD95L (Alexis). After 3-hour incubation at room temperature, the reaction was developed by subsequent incubations with streptavidin, horseradish peroxidase, and tetramethyl-benzidine (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL).

Immunoprecipitation, electrophoresis, and Western blotting.

In immunoprecipitation experiments, Daudi cells were cultured at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL in the absence or presence of 200 U/mL IFN-α for 24 hours. After stimulation, cells were washed and lysed in 1 mL ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM/L Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM/L NaCl, 1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 mM/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 mM/L Na3VO4, and 10% glycerol) at 4°C for 20 minutes. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifuging for 10 minutes at 12 000g at 4°C, and protein concentration was determined by performing a Bradford assay.

Supernatants (500 μg protein/sample) were precleared with protein G–agarose beads (Boehringer Mannheim) and incubated with 20 μg/mL antihuman CD95 antibody (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) or isotypic control antibody (DAKO) for 2 hours at 4°C. Protein-Ig complexes were captured by incubating for 3 hours with protein G–agarose followed by 3 washes in Ripa buffer. Immunoprecipitates were eluted in sample buffer and were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE, 12% acrylamide gel). Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) protein membrane.

After residual binding sites were blocked on the transfer membrane by incubating the membrane with 0.2% I-block/tris-buffered saline–tween (TBS-T) (50 mM/L Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM/L NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) for 18 hours at 4°C, the filter was incubated for 2 hours with anti–TNF-α antibody (Pharmingen) or anti-CD95 antibody (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). After washing in TBS-T, the filter was incubated for 2 hours with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated sheep antimouse Ig (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) and washed again. Antibody binding was visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Radiolabeling of recTNF-α.

RecTNF-α was labeled with sodium iodide 125 using standard techniques.27 Briefly, 100 μg TNF-α (1.1 nM), 2 mCi125I-NaI, and 5 μg lactoperoxidase were added in a vial, and the reaction mixture was slowly stirred at pH 7 (0.01 M balance phosphate buffer) for 10 minutes and thereafter subjected to preparative-gradient high-performance liquid chromatography (RP C18 column, MeCN gradient). The column eluent was passed through a scintillation radioactivity detector and a UV (280 nm) detector in series. The system was calibrated with unlabeled TNF-α and allowed the collection of pure radioiodinated TNF-α, separated from unlabeled TNF-α and from reagents and inorganic iodine species.125I–TNF-α was isolated in a 70% yield at a specific activity of 2000 Ci/mM. The 125I–TNF-α product fraction was stabilized by the addition of 2% human serum albumin and was analyzed by analytic high-performance liquid chromatography (same system as the preparative one), paper electrophoresis (zone electrophoresis on 3MM paper [Whatman Chemical, Clifton, NJ], 0.1 M barbital buffer, pH 8.6, field 300 V for 10 minutes), and trichloroacetic acid protein precipitation. Radiochemical purity was greater than 97% and remained stable for more than 14 days at −20°C.

Binding assay.

In saturation studies, Daudi cells (5 × 105 cells per tube) were incubated in assay buffer containing 50 mM/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 5 nM/L MgCl2 with increasing concentrations of125I–TNF-α (0.01-500 nM/L) in the absence (total binding) or the presence of unlabeled TNF-α (1 μM/L, nonspecific binding) for 60 minutes at 4°C. Displacement studies were performed with 2.5 ng/mL 125I–TNF-α without (total binding) or with (nonspecific binding) increasing concentrations of unlabeled TNF-α or recCD95L, and anti-TNF or recCD95:Fc antibodies. After incubation, the reaction mixture was diluted 1:10 with assay buffer (4°C) and centrifuged (5000g, 10 minutes, 4°C) to separate the membrane-bound from the free ligand. The resultant pellet was washed twice in buffer. Radioactivity of the samples was counted in a gamma counter and calculated according to Scatchard analysis.28

Enhancement and blocking of IFN-induced cell death.

Monoclonal antibodies and reagents—anti-CD95 antibody (clone SM 1/17 [IgG-1] and clone SM 1/23 [IgG-2b])—were purchased from Bender Med Systems (Vienna, Austria), the antihuman CD95 IgM antibody (clone CH-11) from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Antihuman TNF-α–neutralizing antibody and soluble TNF receptor 1 were obtained from R&D Systems. RecCD95:Fc-IgG was purchased from Alexis, interleukin converting enzyme (ICE)–inhibitor I was purchased from Calbiochem-Novabiochem (San Diego, CA), and the CPP32 inhibitor DEVD-CHO was obtained from Clontech.

Daudi cells (5 × 105/mL) were cultured with IFN-α (200 U/mL) in the presence of the following reagents: anti-CD95 IgG antibody, anti-CD95 IgM antibody, anti-CD95L antibody, anti–TNF-α antibody, soluble TNF receptor inhibitor (RI), ICE-inhibitor I, rec CD95:Fc-IgG or CPP32 inhibitor in 48-well culture dishes. All experiments were performed in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS. After 72-hour incubation, cells were harvested and prepared for the detection of apoptosis.

Results

Induction of apoptosis and CD95 expression in IFN-sensitive Daudi cells

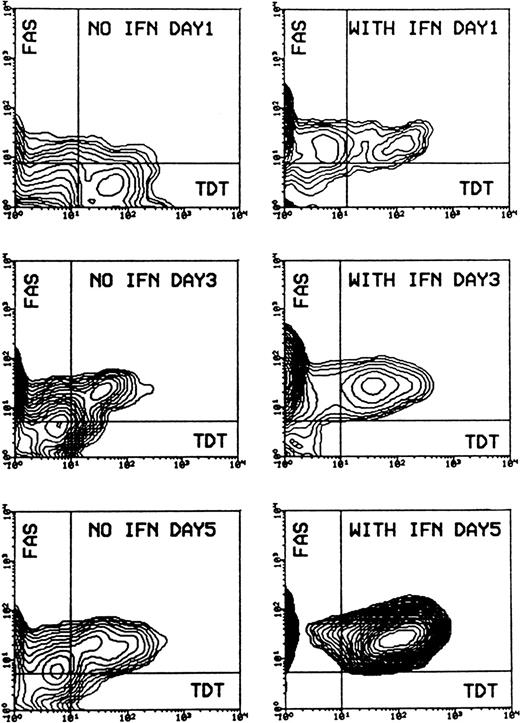

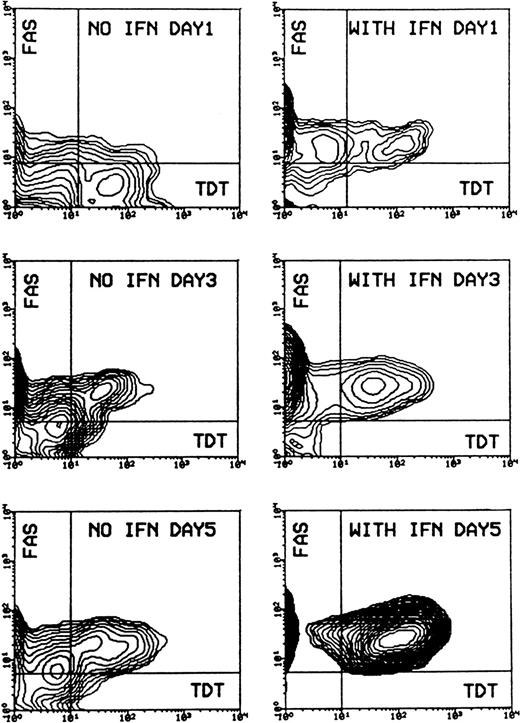

Evaluation of cell morphology and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis showed that IFN-α induced cell death in Daudi cells, beginning after 2 days of incubation and increasing to a mean value of 81% (SD ± 0.58%) apoptotic cells after 5 days, compared to a mean value of 11% (SD ± 4.7%) in the control experiment. Apoptosis was preceded by an enhanced expression of CD95 on Daudi cells after 1-day incubation. Receptor expression reached a maximum after 3 days and remained at this level for up to 5 days. Most of the CD95-expressing cells could be detected as apoptotic cells when double staining was applied. The percentage of CD95-TdT double-positive cells rose from a mean value of 14.8% (SD ± 4.7%) after 3 days of IFN-α treatment to a mean value of 83.6% (SD ± 9.3%) after 5 days (Figure 1).

Induction of apoptosis and expression of CD95 (FAS/APO-1) receptor in Daudi cells in the absence or presence of IFN-α.

Cells were incubated without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α for 1, 3, and 5 days. Cells were then subjected to double staining for Tdt-mediated dUTP-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL) and CD95 expression and flow cytometry analysis. The population of TUNEL+/CD95+ cells was gated in the analysis by the use of negative control antibodies. Data are representative of 1 of 4 experiments.

Induction of apoptosis and expression of CD95 (FAS/APO-1) receptor in Daudi cells in the absence or presence of IFN-α.

Cells were incubated without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α for 1, 3, and 5 days. Cells were then subjected to double staining for Tdt-mediated dUTP-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL) and CD95 expression and flow cytometry analysis. The population of TUNEL+/CD95+ cells was gated in the analysis by the use of negative control antibodies. Data are representative of 1 of 4 experiments.

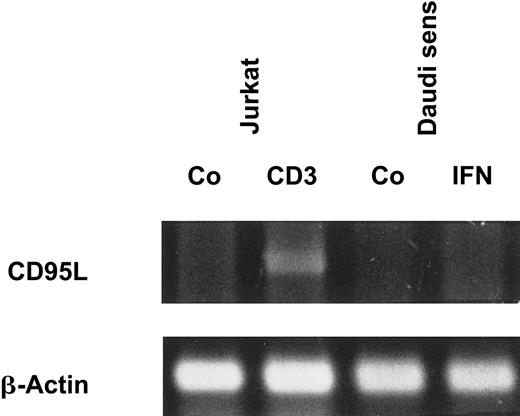

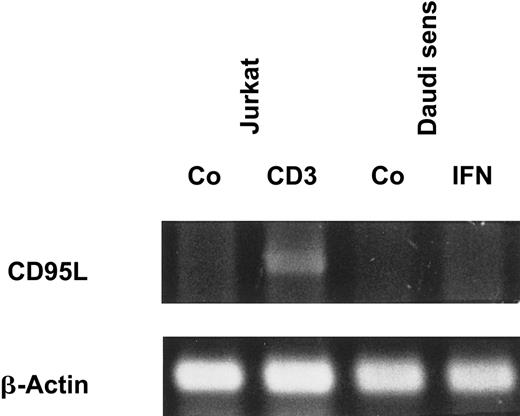

Because there was a strong correlation between IFN-α–induced apoptosis and CD95 expression, we investigated whether IFN-α also stimulates the production and release of CD95L. However, we could not detect CD95L on the cell surfaces of IFN-sensitive Daudi cells by flow cytometry (data not shown). Even after treatment of the cells with a metalloproteinase inhibitor, which is known to block the release of the protein from the cell surface, CD95L was not detectable. In addition, soluble CD95L was not detectable by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in supernatants of IFN-treated Daudi cells (data not shown). These results were confirmed by RT-PCR because messenger RNA (mRNA) encoding the CD95L could not be detected in Daudi cells after exposure to IFN-α (Figure2).

IFN-α does not induce CD95L mRNA expression.

Daudi cells were stimulated as indicated for 20 hours. Jurkat cells, which were cultured with medium or coated CD3 monoclonal antibody for 4 hours, were used as positive control (Co). mRNA levels of CD95L and β-actin were assessed by RT-PCR, and PCR products were visualized after electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel.

IFN-α does not induce CD95L mRNA expression.

Daudi cells were stimulated as indicated for 20 hours. Jurkat cells, which were cultured with medium or coated CD3 monoclonal antibody for 4 hours, were used as positive control (Co). mRNA levels of CD95L and β-actin were assessed by RT-PCR, and PCR products were visualized after electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel.

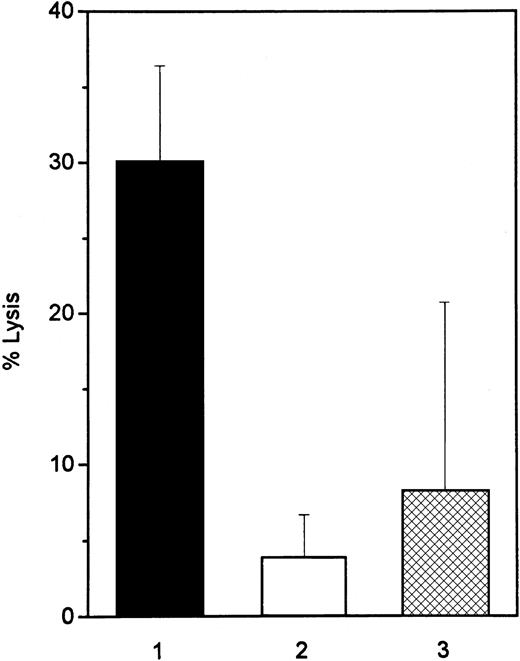

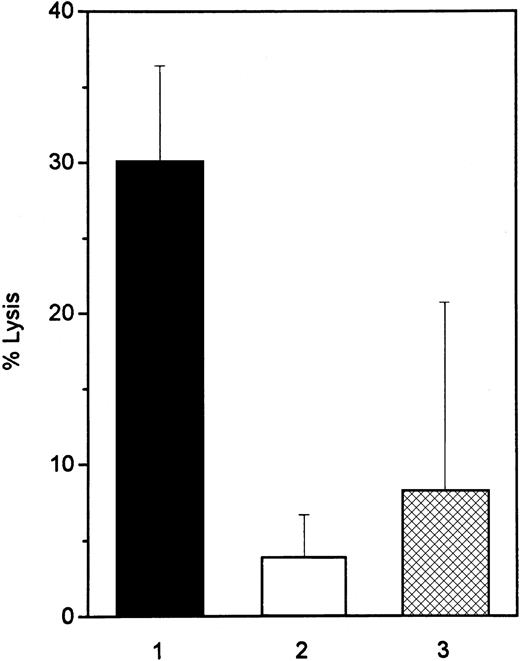

Cytotoxicity of IFN-treated Daudi supernatant

To examine whether a soluble protein in cell supernatants of IFN-treated Daudi cells acts as a ligand for the CD95 receptor, we used the CD95-sensitive T-cell line Jurkat as a target cell in a51Cr release bioassay. After 2-day incubation of Jurkat cells with the supernatants of IFN-treated Daudi cells, cell lysis was observed in 30% of the target cells. Blocking antibodies to TNF-α inhibited apoptosis of Jurkat cells, mediated by supernatants of IFN-treated Daudi cells, by 47% (mean value of morphologic analysis of 3 different experiments). Supernatants of the IFN-treated, IFN-resistant cell lines (IFN-resistant Daudi and Raji) lysed only 4% and 8% of the target cells, respectively, after 2-day culture (Figure3). Incubation of Jurkat cells with 200 U/mL IFN-α for 3 days did not induce apoptosis (data not shown). A direct effect of IFN-α on Jurkat cells could, therefore, be excluded.

CD95-dependent killing activity of IFN-treated Daudi and Raji cells.

The lytic activity of supernatants from 3-day IFN-α–treated Daudi (▪, IFN-sensitive, and ■, IFN-resistant) and Raji (▩) cells was determined in a 48-hour 51Cr-release assay. CD95-sensitive Jurkat cells were used as target cells. Data are representative of 4 experiments.

CD95-dependent killing activity of IFN-treated Daudi and Raji cells.

The lytic activity of supernatants from 3-day IFN-α–treated Daudi (▪, IFN-sensitive, and ■, IFN-resistant) and Raji (▩) cells was determined in a 48-hour 51Cr-release assay. CD95-sensitive Jurkat cells were used as target cells. Data are representative of 4 experiments.

IFN-α induces TNF-α release and caspase-3 activity

Because CD95L could be excluded as the causative ligand that induces cell death in CD95-sensitive Jurkat cells, supernatants of Daudi cells were analyzed for the presence of TNF-α. We observed that Daudi cells started to release measurable amounts of TNF-α after 3 hours of incubation with IFN-α, and the TNF-α level reached a peak after 48 hours. Beyond this time point, TNF-α levels dropped probably because of a large percentage of apoptotic cells (Figure4A). When these cells were incubated in RPMI as control without IFN-α, we observed only a slight increase of the TNF-α levels with cell overgrowth that was accompanied by an increase of apoptotic cells after 3 days. Daudi cells initially expressed little TNF receptor 1 (p55), but it increased slightly during exposure to IFN-α (Figure 4B). In addition, caspase-3 activity increased during incubation of the cells with IFN-α and showed 2 peak values. The first peak value reached a 1.7-fold increase after 15-minute incubation of the cells with IFN-α and dropped to baseline level after 3 hours. Caspase-3 activity started again to increase 48 hours after the increase of TNF levels and reached a second peak, a 3-fold increase, compared to the control activity after 72 hours. This second increase of caspase-3 activity was accompanied by the induction of apoptosis (Figure 4A).

TNF-α release and induction of caspase-3 activity and TNF receptor 1 expression during the exposure of Daudi cells to IFN-α.

(A) TNF-α concentration (pg/mL) was determined by ELISA in culture supernatants collected 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes and 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours after incubation with IFN-α (▪) or without IFN-α (▴). Caspase-3 activity was analyzed as described in “Materials and methods.” Daudi cells were treated with IFN-α at the same time points as for the ELISA. Uninduced cells were used as a control (shown as 100% of baseline [dotted line]). Caspase-3 activity is expressed as a percentage of optical density of the control cells (●). (B) Expression of TNF receptor 1 (p55) in absence or presence of IFN-α. Cells were incubated without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α as before. TNF receptor 1 expression was measured by flow cytometry applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics expressed by the D value.

TNF-α release and induction of caspase-3 activity and TNF receptor 1 expression during the exposure of Daudi cells to IFN-α.

(A) TNF-α concentration (pg/mL) was determined by ELISA in culture supernatants collected 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes and 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours after incubation with IFN-α (▪) or without IFN-α (▴). Caspase-3 activity was analyzed as described in “Materials and methods.” Daudi cells were treated with IFN-α at the same time points as for the ELISA. Uninduced cells were used as a control (shown as 100% of baseline [dotted line]). Caspase-3 activity is expressed as a percentage of optical density of the control cells (●). (B) Expression of TNF receptor 1 (p55) in absence or presence of IFN-α. Cells were incubated without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α as before. TNF receptor 1 expression was measured by flow cytometry applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics expressed by the D value.

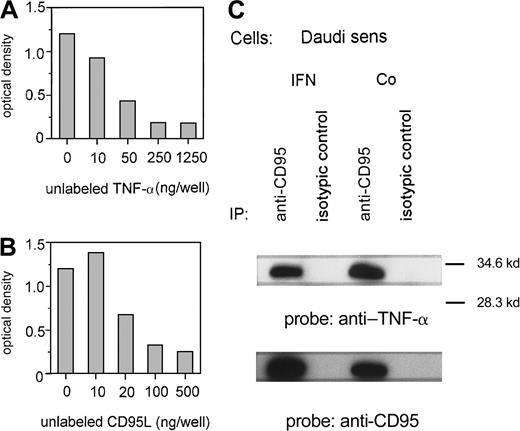

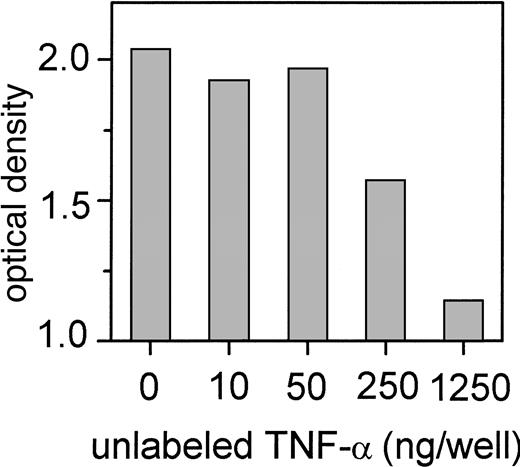

Binding of TNF-α to CD95

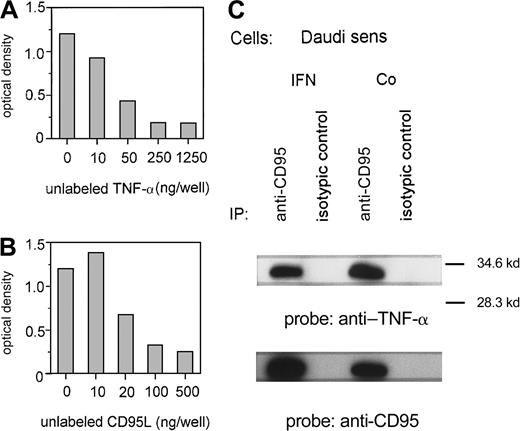

Because TNF-α was stimulated by IFN-α without a marked change of TNF receptor 1 expression, we investigated a potential interaction between TNF-α and the CD95 receptor. First, we proved the in vitro binding of TNF-α to CD95 using an ELISA technique with immobilized CD95:Fc-IgG. Increasing concentrations of unlabeled recTNF-α (Figure5A) or recCD95L (Figure 5B) can suppress the binding of labeled TNF-α to CD95. In addition, we demonstrated in an immunoprecipitation assay that TNF-α, which is released by IFN-sensitive Daudi cells after exposure to IFN-α, binds to the CD95 receptor. TNF-α was detected by an anti–TNF-α antibody on CD95 receptor precipitates of IFN-treated and untreated Daudi cells (Figure5C).

TNF-α and the CD95 receptor.

(A, B) Binding of TNF-α to immobilized recCD95:Fc determined by ELISA. Competition of binding of labeled TNF-α (50 ng/well) by various concentrations of unlabeled recTNF-α (A) or unlabeled recCD95L (B). Figure represents 1 of 3 experiments. (C) Untreated (Co) or IFN-α–treated (IFN) Daudi cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-CD95 antibody or isotypic control antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was probed with anti–TNF-α and reprobed with anti-CD95 antibody.

TNF-α and the CD95 receptor.

(A, B) Binding of TNF-α to immobilized recCD95:Fc determined by ELISA. Competition of binding of labeled TNF-α (50 ng/well) by various concentrations of unlabeled recTNF-α (A) or unlabeled recCD95L (B). Figure represents 1 of 3 experiments. (C) Untreated (Co) or IFN-α–treated (IFN) Daudi cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-CD95 antibody or isotypic control antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was probed with anti–TNF-α and reprobed with anti-CD95 antibody.

Specific binding of radiolabeled TNF-α to Daudi cells, enhancement by IFN-α

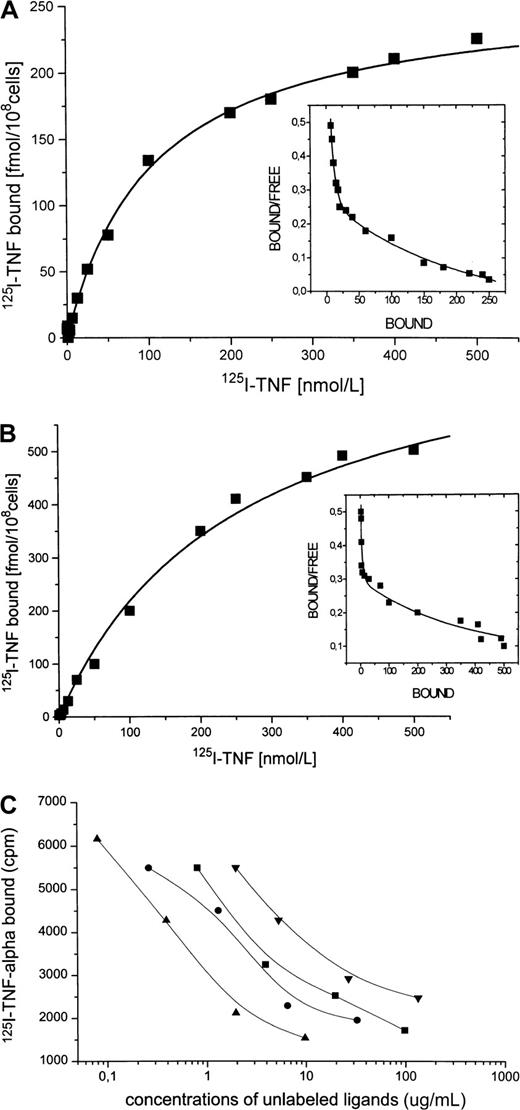

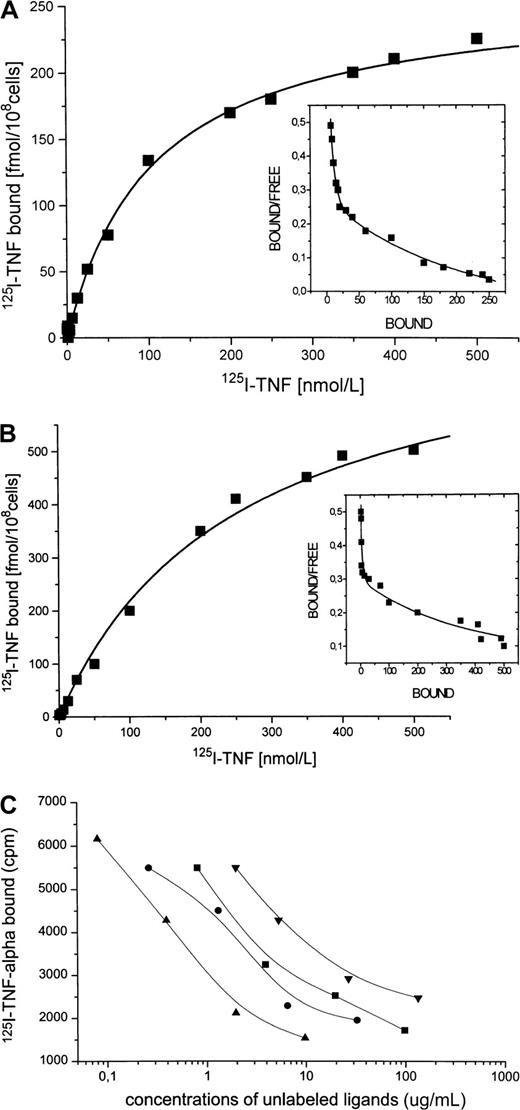

Because Daudi cells spontaneously express only small amounts of CD95 receptor and IFN-α has been shown to enhance CD95 receptor expression, we investigated whether IFN-α treatment also increases the number of binding sites for TNF-α. A representative saturation experiment of 125I–TNF-α binding to Daudi cells is shown in Figure 6A, which indicates 2 classes of specific binding sites with a maximal binding capacity (Bmax1) of 30 fmol/108 cells (Kd1 = 5 nM) for the high-affinity binding sites and of 250 fmol/108 cells (Kd2 = 110 nM) for the low-affinity binding sites. After incubation of the cells with IFN-α (Figure 6B), the high-affinity binding sites for TNF-α (Kd1 = 3 nM) were almost unchanged in number (Bmax1 = 25 fmol/108 cells), whereas the lower affinity sites (Kd2 = 120 nM) were markedly increased (Bmax2 = 550 fmol/108cells). Displacement of 125I–TNF-α binding to Daudi cells was strongly induced by recCD95L (IC50 = 1.0 μg/mL), by anti–TNF-α monoclonal antibody (IC50 = 4.2 μg/mL), by unlabeled TNF-α (IC50 = 7.4 μg/mL), and by the recCD95:Fc fragment (IC50 = 12.0 μg/mL) (Figure 6C), whereas recombinant erythropoietin did not inhibit the binding of 125I–TNF-α .

125I–TNF-α and Daudi cells.

(A) Binding of 125I–TNF-α to untreated Daudi cells. Specific binding (shown) was determined as total binding minus nonspecific binding. This experiment identifies 2 classes of specific binding sites with the binding capacities Bmax1 = 30 fmol/108 cells and Bmax2 = 250 fmol/108 cells with the correspondingKd1 of 5 nM and Kd2 of 110 nM. (B) Binding of 125I–TNF-α to Daudi cells after 1-day incubation with IFN-α. Binding capacity of the high-affinity site remained almost unchanged (Bmax1 = 25 fmol/108 cells, Kd1 = 3 nM), whereas Bmax2 of the low-affinity binding site increased to 550 fmol/108 cells with a correspondingKd2 of 120 nM. (C) Displacement of125I–TNF-α binding to Daudi cells. Incubation of IFN-treated Daudi cells with 125I–TNF-α (2.5 ng/mL) in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled recCD95L (▴, 0.08-9.75 μg/mL), or anti-TNF antibody (●, 0.26-32.5 μg/mL), or recTNF-α (▪, 0.8-97.5 μg/mL), or recCD95:Fc (▾, 1.1-133.1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 4°C.

125I–TNF-α and Daudi cells.

(A) Binding of 125I–TNF-α to untreated Daudi cells. Specific binding (shown) was determined as total binding minus nonspecific binding. This experiment identifies 2 classes of specific binding sites with the binding capacities Bmax1 = 30 fmol/108 cells and Bmax2 = 250 fmol/108 cells with the correspondingKd1 of 5 nM and Kd2 of 110 nM. (B) Binding of 125I–TNF-α to Daudi cells after 1-day incubation with IFN-α. Binding capacity of the high-affinity site remained almost unchanged (Bmax1 = 25 fmol/108 cells, Kd1 = 3 nM), whereas Bmax2 of the low-affinity binding site increased to 550 fmol/108 cells with a correspondingKd2 of 120 nM. (C) Displacement of125I–TNF-α binding to Daudi cells. Incubation of IFN-treated Daudi cells with 125I–TNF-α (2.5 ng/mL) in the presence of increasing concentrations of unlabeled recCD95L (▴, 0.08-9.75 μg/mL), or anti-TNF antibody (●, 0.26-32.5 μg/mL), or recTNF-α (▪, 0.8-97.5 μg/mL), or recCD95:Fc (▾, 1.1-133.1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 4°C.

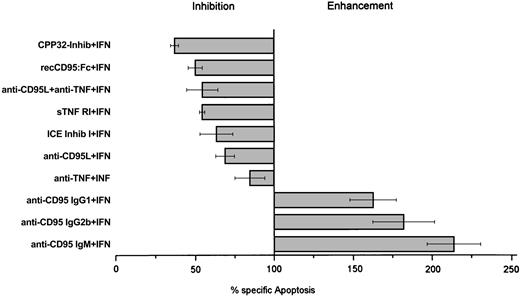

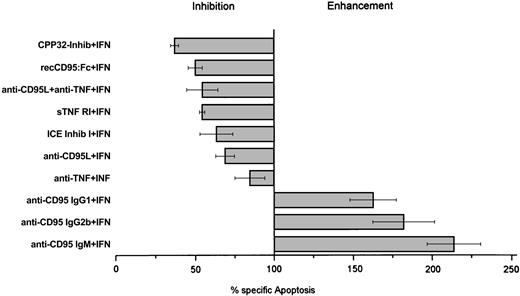

Enhancement and blocking of IFN-α–induced cell death

Coincubation of IFN-α and anti-CD95 antibodies (clones CH-11, SM 1/17, and SM 1/23) enhanced IFN-induced cell death by 50% to 100%, which provides further evidence for the fact that the CD95-mediated pathway is involved in IFN-induced cell death of Daudi cells (Figure7). In contrast, incubation of Daudi cells with these antibodies alone (without IFN) did not induce cell death (data not shown).

IFN-α–mediated apoptosis in Daudi cells.

Effect of CPP32-inhibitor (0.5 μM), recCD95:Fc (25 μg/mL), anti-CD95L antibody (5 μg/mL), anti–TNF-α antibody (100 ng/mL), sTNF RI (100 ng/mL), ICE-inhibitor I (100 nM), anti-CD95 IgG (5 μg/mL), and anti-CD95 IgM (100 ng/mL) antibodies on IFN-α–mediated apoptosis in Daudi cells. Inhibition and enhancement were calculated as reduction or increase of apoptosis compared to apoptosis of IFN-α–treated cells set as 100%. Cells were cultured for 3 days and collected, and percentage apoptosis was determined by morphology. Results represent median values from at least 4 experiments.

IFN-α–mediated apoptosis in Daudi cells.

Effect of CPP32-inhibitor (0.5 μM), recCD95:Fc (25 μg/mL), anti-CD95L antibody (5 μg/mL), anti–TNF-α antibody (100 ng/mL), sTNF RI (100 ng/mL), ICE-inhibitor I (100 nM), anti-CD95 IgG (5 μg/mL), and anti-CD95 IgM (100 ng/mL) antibodies on IFN-α–mediated apoptosis in Daudi cells. Inhibition and enhancement were calculated as reduction or increase of apoptosis compared to apoptosis of IFN-α–treated cells set as 100%. Cells were cultured for 3 days and collected, and percentage apoptosis was determined by morphology. Results represent median values from at least 4 experiments.

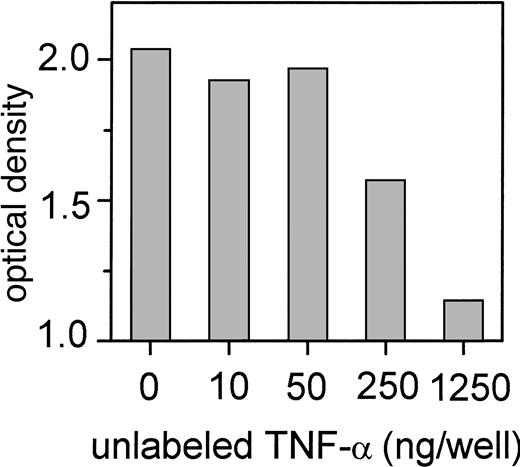

To further confirm our finding of the functional role of the CD95-mediated pathway and the cross-talk of TNF-α with the CD95 receptor during IFN-induced cell death, we incubated IFN-sensitive Daudi cells with 200 U/mL IFN-α and antagonists of the CD95/CD95L- and TNF-mediated apoptosis pathway. Neutralization of nearly 70% of IFN-induced apoptosis was seen when IFN-treated IFN-sensitive Daudi cells were incubated with the CPP32 inhibitor, which was the most efficient inhibitor. The recCD95:Fc fragment inhibited IFN-α–mediated apoptosis by 50% (Figure 7). A less pronounced effect was observed when soluble TNF receptor 1 (p55) or an antibody against TNF-α or the ICE inhibitor I was applied. Although there was no detectable CD95L production, an anti-CD95L antibody did also suppress IFN-induced apoptosis. Binding of anti-CD95L to TNF-α explains this phenomenon, as we demonstrated by ELISA (Figure8).

Binding of TNF-α to immobilized anti-CD95L antibody (clone NOK-1) determined by ELISA.

Competition of binding of labeled recTNF-α (50 ng/well) by various concentrations of unlabeled TNF-α.

Binding of TNF-α to immobilized anti-CD95L antibody (clone NOK-1) determined by ELISA.

Competition of binding of labeled recTNF-α (50 ng/well) by various concentrations of unlabeled TNF-α.

Discussion

The present investigation shows that cross-talking between TNF-α and the CD95 receptor occurs as part of the mechanism of IFN-α– induced autocrine cell suicide in Daudi cells. The CD95 receptor can be considered a third TNF receptor, in addition to p55 and p75. This finding is confirmed by our investigation applying 3 different techniques for binding studies: (1) by ELISA, showing a binding of TNF-α to an immobilized CD95:Fc fragment; (2) by an immunoprecipitation assay, with binding of TNF-α to CD95 receptor precipitates using lysates of Daudi cells; and (3) by the binding of radiolabeled TNF-α to Daudi cells, which is enhanced by IFN-α treatment and which could be efficiently inhibited by CD95L, CD95:Fc, unlabeled TNF-α, and anti-TNF antibody. Two types of TNF binding sites, low- and high-affinity binding sites, were detected by the radiolabeling of Daudi cells. Only the low-affinity TNF-α binding sites were markedly enhanced by IFN-α. The strong enhancement of low-affinity TNF-α binding sites corresponds with the strong induction of CD95 expression during exposure of the cells to IFN-α. In contrast, the weak initial expression of TNF receptor 1 increased only slightly during exposure to IFN-α—corresponding to high-affinity TNF-α binding sites that remained nearly uninfluenced by IFN-α. These findings suggest that the CD95 receptor acts as a low-affinity binding site for TNF-α. The present findings have recently been confirmed in a mouse model in which CD95 contributes to vaginal cell death observed during the estrus cycle and after estrogen deprivation.29 These authors demonstrated that vaginal cell death occurred after estrogen deprivation in CD95L-lacking gld mutant mice, whereas this phenomenon was not observed in TNF-α–deficient mice; in addition, they demonstrated that TNF-α, as it did in our experiments, binds to CD95.

Apoptotic cell death was preceded in our investigation by a strong release of TNF-α and a strong induction of CD95 expression during exposure of the cells to IFN-α. Nearly all CD95+ cells could be identified as apoptotic cells after 3 days of IFN-α treatment. CD95L does not play a role in IFN-induced apoptosis in Daudi cells. CD95L could not be detected in IFN-sensitive Daudi cells, neither on protein nor on an mRNA level, a finding that has also been observed during anti-μ–induced Daudi cell death.30Therefore, CD95L can be excluded as a trigger for the formation of the signaling cascade in the present model of apoptosis induction. Ligation of CD95 has been observed to cause clustering of receptors of the death domain, and it activates Fas-associated death domain (FADD) with a consecutive activation of caspase-8, caspase-9, and the effector caspases including caspase-3,31-34 which was also observed in our experiments when Daudi cells were exposed to IFN-α. Even though there was an increase of caspase-3 activity immediately after exposure of the cells to IFN-α that did not cause apoptosis, the second peak of caspase-3 activity correlated with the initiation of apoptosis. Because the increase of caspase-3 activity followed the rise of TNF-levels, it is very likely that increased caspase-3 activity is triggered by TNF-α.

Inhibition of IFN-α–mediated cell death by the preincubation of Daudi cells with recCD95:Fc-IgG, anti-TNF antibodies, soluble TNF receptor I (p55), ICE inhibitor, or CPP32 inhibitor—in addition to IFN-α—further supports our finding of the involvement of CD95, TNF-α, and caspase-3 in IFN-α–mediated cell death. It has already been shown that ICE is involved in CD95-mediated apoptosis and that both ICE inhibitor and CPP32 inhibitor can suppress CD95/CD95L-mediated apoptosis.35 ICE can process CPP32, which is located downstream in the signaling cascade. In accordance with a previous report, CPP32 inhibitor was more potent in the suppression of IFN-α–mediated cell death than ICE inhibitor in our study.36

The blockade of CD95 receptor/TNF-α–mediated apoptosis in our cell line did not fully inhibit IFN-α–mediated apoptosis, similar to the IFN-α–induced CD95/CD95L-mediated apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells.37 Besides CD95, other death receptors may have direct access to the caspase machinery. Recently the up-regulation of Bax expression by IFN-α in Daudi cells was shown.38Ectopic expression of Bax may induce apoptosis through the release of cytochrome c, which consecutively activates caspase- 3.39,40 The findings of insufficient inhibition of IFN-α–induced apoptosis, even after blockade of the caspase cascade, demonstrate that different caspase-independent pathways may exist that mediate the IFN-α–induced death signal.41

Similar to the mechanism during activation-induced cell death in which the engagement of T-cell receptor leads to an increased expression of CD95 and a release of CD95 ligand,7 in our experiments IFN-α acted as the inducer of CD95 expression and release of TNF-α. The model of CD95 receptor-mediated cell killing has been suggested as a major effector mechanism by which T cells eliminate hematopoietic cells in aplastic anemia.42 Elevated levels of TNF-α and IFN-α might induce CD95 expression on CD34+ marrow cells in aplastic anemia.43,44 There are some reports on the activation of CD95 expression on CD34+ cells during incubation with IFN-α in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, a phenomenon that does not occur with the same intensity in normal cells.17 18 Neither in aplastic anemia nor in chronic myeloid leukemia, a ligand for the CD95 receptor on hemopoietic cells could be identified. Our model of IFN-induced apoptosis, with the detection of cross-talk between CD95 receptor and TNF-α in the Daudi cell line, can therefore be considered part of the mechanism of action of IFN-α treatment. Moreover, this finding may be very important for new insights into the pathogenesis of various autoimmune disorders.

In conclusion, the present model of IFN-induced cell death demonstrates for the first time activation of an autocrine loop with the up-regulation of a receptor and a ligand of the death domain in IFN-sensitive Daudi cells. Surprisingly, and most important, we could not detect CD95L but found cross-talk between CD95 receptor and TNF-α during the exposure of Daudi cells to IFN-α.

We thank Dr Meir Wetzler (Roswell Park Cancer Center Institute, Buffalo, NY) for helpful discussion and technical advice about the immunoprecipitation assay, and we thank Dr G. R. Adolf (Boehringer Ingelheim, Vienna, Austria) for kindly providing the recTNF-α.

Supported by the Max Kade Foundation (New York, NY) and the Kommission Onkologie of the University of Vienna and by National Institutes of Health grants CA 55/64 and CA 16672 (M.A. and S.J.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Heinz Gisslinger, Department of Internal Medicine I, Division of Hematology and Blood Coagulation, Währinger Gürtel 18-20, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail:heinz.gisslinger@akh-wien.ac.at.

![Fig. 4. TNF-α release and induction of caspase-3 activity and TNF receptor 1 expression during the exposure of Daudi cells to IFN-α. / (A) TNF-α concentration (pg/mL) was determined by ELISA in culture supernatants collected 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes and 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours after incubation with IFN-α (▪) or without IFN-α (▴). Caspase-3 activity was analyzed as described in “Materials and methods.” Daudi cells were treated with IFN-α at the same time points as for the ELISA. Uninduced cells were used as a control (shown as 100% of baseline [dotted line]). Caspase-3 activity is expressed as a percentage of optical density of the control cells (●). (B) Expression of TNF receptor 1 (p55) in absence or presence of IFN-α. Cells were incubated without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α as before. TNF receptor 1 expression was measured by flow cytometry applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics expressed by the D value.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/9/10.1182_blood.v97.9.2791/6/m_h80910980004.jpeg?Expires=1765486019&Signature=oKz2P4c0feSEse0hu7yS5Obk-YBgQ2X7BDXr~CfUnAyYDFIf4hHPnXnnEuEhnx8x9kv50aSav7bW5mqCrLIJGIAsn8HF-6nT-5OuUux6xvf-mELQPBAuI69OcMKSMmBVB-81vVCHJIDbdhYmSGST8zBLW~-YDKUknG8ks9GfkehB6eYs~jrgLpepU4wWvNesJkxwAoyV-q8Ur0j6mKbf~pmkq0cUZaORxAv4VMW5sshoeFA9L09E5u4Kfm3IbYVPrgDHaSXs9b1fgqMzgnFYabKiErjQvx827BjaMBkT2N6ZeIJ5yML-fHxyz8MB4PnH1XfuRmxMBAaP2qtOt9TlbA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. TNF-α release and induction of caspase-3 activity and TNF receptor 1 expression during the exposure of Daudi cells to IFN-α. / (A) TNF-α concentration (pg/mL) was determined by ELISA in culture supernatants collected 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes and 3, 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours after incubation with IFN-α (▪) or without IFN-α (▴). Caspase-3 activity was analyzed as described in “Materials and methods.” Daudi cells were treated with IFN-α at the same time points as for the ELISA. Uninduced cells were used as a control (shown as 100% of baseline [dotted line]). Caspase-3 activity is expressed as a percentage of optical density of the control cells (●). (B) Expression of TNF receptor 1 (p55) in absence or presence of IFN-α. Cells were incubated without or with 200 U/mL IFN-α as before. TNF receptor 1 expression was measured by flow cytometry applying the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics expressed by the D value.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/97/9/10.1182_blood.v97.9.2791/6/m_h80910980004.jpeg?Expires=1765492484&Signature=VCdOs1XWplYGT2Q0ezRbN6FS0GAITl5gTVU37C7G-0zrtzF0tjbTjvf0TPxAQI8chUB7rQxM~RW4hmlG~tjGwYBWErRQH8R9oadQJZI5Lv~~9G388BXG1n5sOhqdhByWpEcLVQTryTfVWJe5I1raCT28Jot7zp~LW0m2ZS1IQ1b7YAexYmMDqwoZWACg2CIn800hBMTHYM7oGINN01M0N~lX09DMWWBHSPlV0505skOsvBkQWKt9nlWPaTjUOUFQgnDXaEoicQWh7JKJNxoR1xANVOQJZN7te5OSyYtX9W19ioPylJvg4ff8cVgRn8mv9IMVgDsu8o18xgnbGytRFg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)