The occurrence of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in 2 of 3 triplets provided a unique opportunity for the investigation of leukemogenesis and the natural history of ALL. The 2 leukemic triplets were monozygotic twins and shared an identical, acquiredTEL-AML1 genomic fusion sequence indicative of a single-cell origin in utero in one fetus followed by dissemination of clonal progeny to the comonozygotic twin by intraplacental transfer. In accord with this interpretation, clonotypic TEL-AML1 fusion sequences could be amplified from the archived neonatal blood spots of the leukemic twins. The blood spot of the third, healthy, dizygotic triplet was also fusion gene positive in a single segment, though at age 3 years, his blood was found negative by sensitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening for the genomic sequence and by reverse transcription–PCR. Leukemic cells in both twins had, in addition toTEL-AML1 fusion, a deletion of the normal, nonrearrangedTEL allele. However, this genetic change was found by fluorescence in situ hybridization to be subclonal in both twins. Furthermore, mapping of the genomic boundaries of TELdeletions using microsatellite markers indicated that they were individually distinct in the twins and therefore must have arisen as independent and secondary events, probably after birth. These data support a multihit temporal model for the pathogenesis of the common form of childhood leukemia.

Introduction

Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a biologically and clinically diverse cancer.1,2 The major subset (common ALL) has characteristics of B-cell precursors3; the most frequent chromosomal and molecular genetic abnormalities are hyperdiploidy4 andTEL-AML1 gene fusion, the latter generated by cryptic chromosomal translocation.5 6

TEL-AML1 has transcriptional repressor function in model systems,7,8 and it is assumed that this chimeric protein plays a key role in leukemogenesis. Until recently, however, it was unclear whether this fusion represents an initiating event in leukemogenesis and, if it does, when it occurs and what other complementary or secondary genetic changes are necessary. Studies of monozygotic twins with TEL-AML1–positive ALL have provided compelling evidence that this fusion gene can arise in utero,9,10 validated by the finding of clonotypicTEL-AML1 fusion sequences in the neonatal blood spots (Guthrie cards) from singleton children with ALL.11 Taken together with the concordance rate of ALL in identical twins (approximately 5%),9 these data then suggested a multistep model for the pathogenesis of ALL involving in utero initiation and at least one necessary postnatal secondary or promotional event.12 Deletions of the normal, nonrearranged TEL allele are frequent in patients with ALL with TEL-AML1 fusion13 14 suggesting that this could represent a common, though not exclusive, secondary event.

We describe here an unusual set of triplets in whom a monozygotic pair had ALL and their dizygotic twin brother was healthy. Leukemic cells of both identical twins at diagnosis had a TEL-AML1 fusion plus deletion of the nonrearranged TEL allele. Neonatal blood spots (Guthrie cards) were archived and retrievable on all 3 triplets, providing us with a unique opportunity to substantiate the proposed model for the natural history of ALL.

Study design

Pregnancy history and zygosity analysis

The pregnancy was uncomplicated, and there was no exposure to X irradiation. Blood mononuclear cell DNA from the triplets and their parents was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based methods for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotype15 16and microsatellite markers (9 loci in total) to determine zygosity. On this basis, triplets T1 and T2 were typed as monozygotic twins, and triplet T3 was typed as a dizygotic twin.

Clinical history

One of the triplets (T1) had no significant neonatal problems but, at the age of 21 months, was examined for a history of intermittent coryzal symptoms, pallor, and cough (unresponsive to oral antibiotics) over a 2-month period.

Subsequent blood film showed 65% blast cells and a white blood count of 31.4 × 109/L. Bone marrow aspirate showed 99% infiltration by L1 lymphoblasts, which, on routine cytogenetic examination, showed a 46 XY complement. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) identified an occult t(12;21) (see further below). The blasts were HLA DR+, CD19+, and CD10+ but were negative for myeloid markers. The patient was entered in the Medical Research Council ALL 97 therapeutic protocol.

In view of the triplet pregnancy, his 2 brothers were also tested for leukemia. Both had the same coryzal symptoms, but neither had been noted to be pale. Triplet 2 (T2) had a hemoglobin level of 10.3 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 14 × 109/L of which 36% were blasts, and a platelet count of 167 × 109/L. His marrow showed almost total replacement again by L1 lymphoblasts, and an occult t(12;21) was identified on interphase FISH. Blasts were CD10+ and CD19+. He was entered in the same treatment protocol as his brother. Triplet (T3) had a hemoglobin level of 11.2 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 11.2 × 109/L but with no blasts visible, and a platelet count of 201 × 109/L. His bone marrow was completely normal and showed no evidence of leukemic infiltration.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

FISH was carried out on cytogenetic preparation of bone marrow using the LSI TEL-AML1 dual-color probe (Vysis, Richmond, Surrey, United Kingdom) and the alpha satellite centromeric probe specific for chromosome 10 (Appligene-Oncor, Illkirch, France), hybridized according to manufacturers' instructions. The probe specific for TEL spanned exons 1 to 4 and was labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (green), and the second, which spannedAML1, was labeled with rhodamine (red). The translocation split the AML1 signal, moving 5′AML1onto the derived chromosome 12, whereas 3′AML1remained on the derived chromosome 21 and fused with the translocated 5′TEL. This TEL-AML1 fusion could be seen as a red–green (yellow) signal on the derived chromosome 21. Two hundred interphase cells were scored, and metaphases were examined wherever possible.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA from each triplet was extracted from bone marrow cells, and cDNA was generated from approximately 2 μg total RNA using random hexamers essentially as described.9 RT-PCR forTEL-AML1 and ABL control was performed as described therein.

Identification of TEL-AML1 genomic fusion sequences

Amplification of the genomic breakpoint fusion sequences for TEL/AML1 was performed by long-range PCR using conditions previously described17 and with single TEL primers in parallel combination with multi-AML1 primers, as reported for amplification of MLL-AF4 fusions18 (Figure1A).

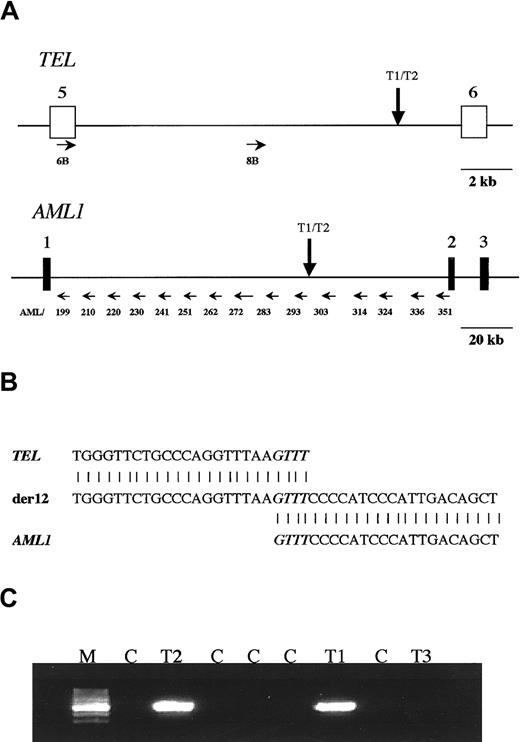

Analysis of TEL-AML1 translocation in a set of triplet twins.

(A) Scheme of TEL and AML1 genes showing where the primers anneal in both genes (small horizontal arrows). The vertical arrows show the map location of the breakpoint betweenTEL and AML1 shared by the 2 leukemic twins. (B) Sequence neighboring the TEL-AML1 breakpoint found in the twins. The normal TEL sequence is shown at the top, the sequence found in the patients is shown in the center, and theAML1 sequence is shown at the bottom. There is a 4-base homology between TEL and AML1 in the breakpoint, which is shown in italics. (C) PCR analysis of the TEL-AML1translocation on the blood DNA of the triplet twins. The predicted PCR product of 521 bp was amplified with primers A and E in twins T1 and T2 but not in twin T3 or any of the control DNA samples. M, marker; T1 and T2, affected twins; T3, healthy twin; C, negative control DNA samples.

Analysis of TEL-AML1 translocation in a set of triplet twins.

(A) Scheme of TEL and AML1 genes showing where the primers anneal in both genes (small horizontal arrows). The vertical arrows show the map location of the breakpoint betweenTEL and AML1 shared by the 2 leukemic twins. (B) Sequence neighboring the TEL-AML1 breakpoint found in the twins. The normal TEL sequence is shown at the top, the sequence found in the patients is shown in the center, and theAML1 sequence is shown at the bottom. There is a 4-base homology between TEL and AML1 in the breakpoint, which is shown in italics. (C) PCR analysis of the TEL-AML1translocation on the blood DNA of the triplet twins. The predicted PCR product of 521 bp was amplified with primers A and E in twins T1 and T2 but not in twin T3 or any of the control DNA samples. M, marker; T1 and T2, affected twins; T3, healthy twin; C, negative control DNA samples.

For TEL, TEL6B-CTCTCATCGGGAAGACCTGGCTTACATG; TEL8B-CCTACAGCAGGCAAGACACAGAATTTCCTC. For AML1 from the 5′ end of intron 1 (Figure 1A), AML199-GGACTCTGGCACCAACCAGCTATGG; AML210-GCAAGCAGTTACTTTCCTGGTCTGCCA; AML220-GGAAGGGCTGGTAGCTTTGGGTCC; AML 230-CTTGGCACCAATGTCCTCTTCACTCC; AML241-GCAGTAGGAGATGGTGTGTGGAACACC; AML251-CCTTCAGAGGGAGCACAGAAATGCC; AML262-CGAACACCGTGGAAGCTCTCTGATGT; AML272-GGTTTACTGCCCTGCTGTCCAGAGG; AML283-CAGATGAAGGAGAAGGTTGCTGTCCTAACA; AML293-ACCATCCTTTGACCTTGGCCTTGC; AML303-GAGGCCATGAGGGTGTGAATCAGG; AML314-CTACAAGGTGTAGAGGTGGCACAGGGTG; AML324-CTCTCTCAGTCAGTGTGAAGCAGGAGCC; AML336-CCAAGTGGAGCATCTGAAAATTGCGC; A ML351-AACGCCTCGCTCATCTTGCCTGG.

Primers TEL6B and TEL8B were used in combination with one primer of each primer of the AML1 set. PCR products were sequenced, and positive bands were identified by comparison with the known wild-type sequences of TEL and AML1 genes, deposited in the databases (GenBank; HSV61375 and HSV63313 for TEL andAF015262 HSA131498, AP000125, AP000173, AP000332 for AML1). The breakpoint sequence was obtained through restriction analysis by primer walking and sequencing.

Analysis of Guthrie blood spots

A novel set of TEL and AML1 primers was designed from sequences around the TEL-AML1 genomic breakpoint to analyze, by conventional or short-range PCR, DNA samples and Guthrie cards from the triplets, as previously described.11 The sequences were: primer A (AML1)-GTTAGCCCAACGATTGCGC; primer B (AML1)-GCCACCCATTTCATGATTGC; primer C (AML1)-CTGAGAATCTTGTGGAATGGAAGC; primer D (TEL1)-CCACACAGCTCTCTCTGTAACCATC; primer E (TEL1)-CATCTCCCACCAACACCAGG.

Positive clonotypic bands yielded from PCR reactions of the Guthrie spots were subsequently purified and sequenced with BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready reaction mix (Applied Biosystems, United Kingdom). Control samples for these tests were segments of Guthrie cards from patients without leukemia.

Molecular microsatellite mapping of 12p (TEL) deletions

Microsatellite mapping was performed essentially as described by Baccichet and Sinett19 using some additional established markers located on 12p. Primer pair sequences for markers D12S352, D12S94, D12S356, D12 S336, D12S77, D12S89, D12S98, D12S320, D12S269, D12S70, D12S310, D12S363, and D12S87 were obtained from the Human Genome Database and the primer DNA from OSWEL (University of Southampton, United Kingdom). DNA (7.5 ng) was subjected to PCR and electrophoresis exactly as described.19 The LOH score was positive if the relative intensity of one allele for an informative marker heterozygous at remission was lost or diminished in the same patient, either at presentation or at relapse.

Results and discussion

Cytogenetics and FISH

Cytogenetic analysis of leukemic blast cells at diagnosis revealed that most cells in T1 had a normal male karyotype. Using a centromeric probe specific for chromosome 10, FISH revealed that a small population (13%) of cells had trisomy 10. T2 had a normal karyotype and no evidence of trisomy 10 on FISH analysis. Both triplets with leukemia (T1, T2) had TEL-AML fusion demonstrable by both FISH (see further below) and RT-PCR, whereas the blood of T3 was RT-PCR–negative for TEL-AML1 mRNA (data not shown). A variable proportion of cells from both T1 and T2 had, in addition to TEL-AML1, a deletion of the other (nonrearranged) TEL allele (see further below).

Identification of genomic TEL-AML1 fusion sequence

Long-distance PCR with several combined primers fromTEL and AML1 genes (Figure 1A) was applied to the diagnostic DNA of T1 and yielded 2 bands (with primer pairs no. 8B, 303 and 314). These were sequenced and yielded a TEL sequence from one side and AML1 from the other. After restriction analysis and further sequencing of this amplicon, the breakpoint was identified in both genes. The breakpoint (Figure 1A) on theTEL side is located close to exon 6; on the AML1side, it is located on the intermediate cluster defined by Wiemels et al.17 As shown in Figure 1B, the resultant fusion gene has a 4-bp homology between TEL and AML1 genes at the breakpoint region. Two primers (primers A and E) were designed to amplify a patient-specific fragment of 521 bp, encompassing the breakpoint. These primers were also used to analyze the DNA from the other 2 triplets. Leukemic cell DNA from T2 shared the same breakpoint as that from T1, but the DNA derived from the normal blood cells of T3 failed to yield any amplifiable fragment (Figure 1C), as did the DNA controls.

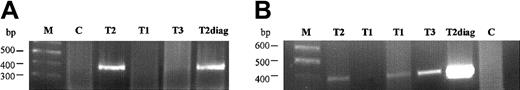

Analysis of Guthrie spots

We tested segments (approximately one eighth) of neonatal blood spots cut from the twins' archived Guthrie cards. Primers C and E were then used to amplify a 231-bp amplicon. The sensitivity of this PCR was first tested using dilutions prepared from the diagnostic (leukemic) DNA of T1 (from 100 ng to 1 pg DNA) and was determined to be 100 pg (data not shown). In screening slices from the blood spots, negative controls were used (nonleukemic samples), and the diagnostic DNA of T2 was used as a positive control for the PCR reaction (Figure2). A second combination of primers (primers B and D) was also tested on the Guthrie spots, with the positive control (leukemic) sample producing a 384-bp fragment (Figure2). From the independent PCR experiments, T1 had 4 positive segments (of 8 tested), T2 had 2 positive segments (of 8 tested), and T3 (the dizygotic, healthy triplet) had a single positive segment (out of 6 tested). By sequencing analysis, all the positive clonotypic bands were confirmed to be identical to the ones amplified from the diagnostic leukemic DNA from T1 and T2.

Analysis of fusion gene sequence in the Guthrie cards of the triplet twins on PCR reactions.

(A, B) First and second PCR reactions, with specific primers B and D amplifying a product of 384 bp. M, marker; T1 and T2, affected twins; T3, healthy twin; C, negative Guthrie controls; T2diag, twin 2 diagnostic DNA.

Analysis of fusion gene sequence in the Guthrie cards of the triplet twins on PCR reactions.

(A, B) First and second PCR reactions, with specific primers B and D amplifying a product of 384 bp. M, marker; T1 and T2, affected twins; T3, healthy twin; C, negative Guthrie controls; T2diag, twin 2 diagnostic DNA.

TEL deletions as secondary/independent and possibly postnatal events

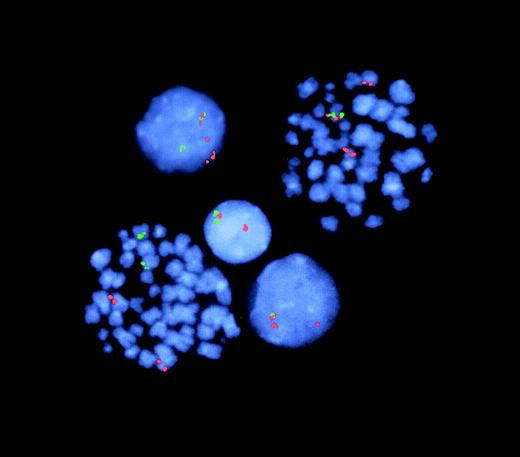

Deletions of the nonrearranged TEL allele are common in patients with ALL with t(12;21) TEL-AML1 fusion. FISH analysis of the leukemic twins' diagnostic samples with 2-colorTEL and AML1 probes produced the results illustrated for T1 in Figure 3. T1, whose disease and clinical symptoms were more advanced, had TELdeletions in most (87%) of cells with TEL-AML1. In T2, only 11% of cells with a TEL-AML1 detectable by FISH had a simultaneous loss of the normal TEL allele (data not shown).TEL deletions were, therefore, subclonal in both twin leukemic cell populations.

FISH analysis of TEL-AML1 fusion and TELdeletion.

Representative cells from T1 (2 metaphases, 3 interphases). The lower left-hand metaphase shows 2 normal signals each for TEL(green) and AML1 (red) with no fusion gene (juxtaposition of 2 colors)—ie, a normal, nonleukemic cell. The right-hand metaphase shows a red–green TEL-AML1 fusion plus the normal and the split AML1 signals. In this cell, the green TELsignal (for the nonrearranged TEL allele) is missing (ie, deleted) from the second chromosome 12. The lower interphase cell similarly has TEL-AML1 fusion plus TEL deletion. In contrast, the upper interphase cell has TEL-AML1 fusion but retains the second TEL (green) allele. The middle interphase cell has normal TEL and AML1 signals (note: in this latter, nonleukemic cell, one TEL and oneAML signal are in proximity but are not overlapping or fused).

FISH analysis of TEL-AML1 fusion and TELdeletion.

Representative cells from T1 (2 metaphases, 3 interphases). The lower left-hand metaphase shows 2 normal signals each for TEL(green) and AML1 (red) with no fusion gene (juxtaposition of 2 colors)—ie, a normal, nonleukemic cell. The right-hand metaphase shows a red–green TEL-AML1 fusion plus the normal and the split AML1 signals. In this cell, the green TELsignal (for the nonrearranged TEL allele) is missing (ie, deleted) from the second chromosome 12. The lower interphase cell similarly has TEL-AML1 fusion plus TEL deletion. In contrast, the upper interphase cell has TEL-AML1 fusion but retains the second TEL (green) allele. The middle interphase cell has normal TEL and AML1 signals (note: in this latter, nonleukemic cell, one TEL and oneAML signal are in proximity but are not overlapping or fused).

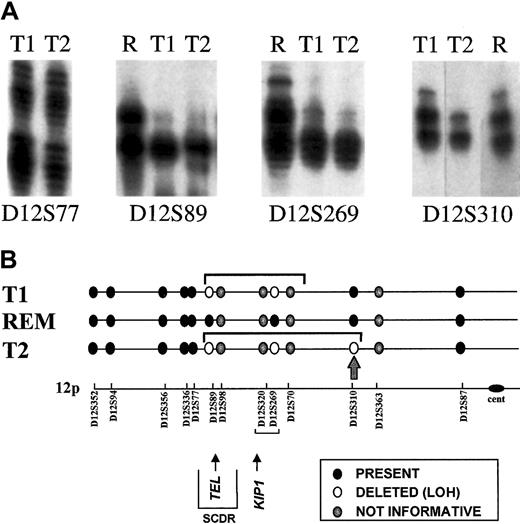

TEL gene deletions have variable breakpoints or boundaries, and these can be mapped using microsatellite markers for which the patient is constitutionally heterozygous.19 If, as the FISH data indicate, TEL deletions are secondary genetic events in the clonal evolution of leukemia, then they should be physically distinct genomic alterations rather than clonotypic and shared. We determined zygosity status for a series of microsatellite markers spanning a region of chromosome 12p (approximately 50 cM) and including the TEL gene. For this purpose, remission blood of the leukemic twins was used. Of 13 markers tested, 9 were informative (ie, heterozygous). Key data on 4 of the markers for the leukemic cells of monozygotic twins 1 and 2 are shown in Figure4A. Figure 4B provides a diagrammatic summary of all the data obtained. TEL deletions in leukemic cell DNA from T1 and T2 had indistinguishable telomeric boundaries (between D12S77 and D12S89) but differed in their centromeric boundaries. There was LOH for marker D12S310 in T2 DNA but not in T1 DNA (Figure 4B, arrow), indicating that T2 leukemic cells had a larger deletion than T1 leukemic cells, extending some considerable distance centromeric of the TEL gene itself. Although we cannot exclude that the more extensive TELdeletion in T2 evolved from the deletion in T1 through, for example, genetic instability, it is, in our view, more likely that these 2 TEL deletions were clonally distinct and arose as 2 separate, independent events in the twins' preleukemic subclones.

Analysis of TEL deletions.

(A) Detection of LOH on chromosome 12p. Allotypes at 4 informative markers are shown for each twin pair at diagnosis (T1, T2) and twin 2 at remission (R). Both twins retain heterozygosity of marker D12577 and show LOH at markers D12S89 Δ D12S269. Twin 1 retains heterozygosity at marker D12S310, but twin 2 shows LOH. Deleted alleles are not entirely diminished because of the subclonal deletion of 12p in the leukemic cells. (B) Schematic representation of chromosome 12p showing position of microsatellite markers. The LOH restricted to T2 is shown by the arrow at D12S310. SCDR shows the shortest commonly deleted region.30 REM, remission DNA analysis (no LOH control).

Analysis of TEL deletions.

(A) Detection of LOH on chromosome 12p. Allotypes at 4 informative markers are shown for each twin pair at diagnosis (T1, T2) and twin 2 at remission (R). Both twins retain heterozygosity of marker D12577 and show LOH at markers D12S89 Δ D12S269. Twin 1 retains heterozygosity at marker D12S310, but twin 2 shows LOH. Deleted alleles are not entirely diminished because of the subclonal deletion of 12p in the leukemic cells. (B) Schematic representation of chromosome 12p showing position of microsatellite markers. The LOH restricted to T2 is shown by the arrow at D12S310. SCDR shows the shortest commonly deleted region.30 REM, remission DNA analysis (no LOH control).

TEL-AML1 gene fusions, in common with other chimeric genes generated by chromosome translocations and illegitimate recombination,20,21 involve clustered but diverse intronic breakpoints.17,22,23 As a consequence each patient's leukemic cells have a unique breakpoint at the level of DNA sequence. The finding of a shared, clonotypic, but nonconstitutiveTEL-AML1 genomic fusion sequence in this pair of twins, as in other twins with concordant ALL,9,10 is then most plausibly interpreted as indicating an origin of the fusion gene in one cell in one fetus in utero, followed by dissemination of the clonal progeny of that cell to the co-twin through the blood and intraplacental anastomoses.24 This suggests thatTEL-AML1 fusion could be a prenatal, initiating event in ALL. This view finds strong experimental support in the demonstration that, for most singleton patients with TEL-AML1fusion-positive ALL in the 2- to 5-year age incidence peak, clonotypic fusion sequences are detectable by retrospective scrutiny (by genomic PCR) of their neonatal blood spots or Guthrie cards.11

In this unique triplet set in which the 2 monozygotic twins had ALL, we provide more support for this view by demonstrating that a clonotypic genomic TEL-AML1 sequence was shared by the diagnostic leukemic cells of the twins and present in their neonatal blood spots. To our surprise, we also found that the same bona fideTEL-AML1 sequence was amplifiable in the neonatal blood spot of the healthy dizygotic triplet. We cannot exclude that this resulted from chance cross-contamination during card collection or in the laboratory, though all concurrent controls were satisfactory. Assuming this was genuine, the presence of a few small preleukemic cells in the neonatal blood of the co-twin, who developed in a physically separate (dichorionic) placenta, may represent tracking of these cells through maternal blood. One report provides evidence that normal fetal cells enter and survive in the maternal circulation,25 and another shows concordance of leukemia in 2 monozygotic twins who had dual or dichorionic placentas.26 The dizygotic triplet (T3) remains healthy 2 years after the diagnosis of ALL in his twin brothers, and his blood has no detectable TEL-AML1 genomic or mRNA sequences. Although this negativity could reflect a dilution effect, it is also possible that preleukemic cells, if they were present in the circulation of T3 at birth, were subsequently eliminated immunologically as genetically foreign.

The concordance rate of ALL in twin children is considered to be approximately 1 in 20, or 5%.9 This indicates the necessity of postnatal exposure and secondary genetic event(s) in accord with the paradigm of multihit pathogenesis of leukemia and other cancers. Leukemic cells at diagnosis of ALL with TEL-AML1frequently have additional genetic abnormalities, the most common of which, as in the patients reported here, is deletion of the normal or nonrearranged TEL allele.13,14 Crucially, theTEL deletion scrutinized simultaneously withTEL-AML1 fusion by dual-color FISH was numerically subclonal in the leukemic cells of both monozygotic twins. Other descriptions ofTEL deletions by FISH in singleton patients with ALL suggest that this genetic abnormality is frequently restricted to a subclone of leukemic cells and, therefore, is most likely a secondary event.27-29 By microsatellite mapping of theTEL deletion boundaries, we provide evidence that the deletions in the leukemic cells of the twins are not the same. This provides evidence that the deletions most likely occurred as 2independent subclonal events. Although we cannot determine the timing of secondary TEL deletions, these data are most compatible with origin after separation of the twins' blood supply, (ie, after birth).

These data add to our understanding of the temporal sequence of molecular genetic events in the pathogenesis and natural history of childhood ALL.12 They leave unresolved a number of critical questions, including the minimal number of genetic events required (2 or more), the precise developmental timing of gene fusions and deletions, and the causal mechanisms involved.

We thank Simon Dearden, Michelle Ayres, Nick Telford, Mary Martineau, and Dr J. Wiemels for technical help and advice, and we thank Ms B. Deverson for assistance in preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by the specialized programs of the Leukaemia Research Fund, United Kingdom (M.F.G., A.M.F., G.R.J., C.J.H.), the PRAXIS XXI scholarship from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (A.T.M.), the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund (G.M.T., M.F.G.), and the Cancer Research Campaign (O.B.E.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mel F. Greaves, LRF Centre, Institute of Cancer Research, Chester Beatty Laboratories, 237 Fulham Rd, London SW3 6JB, United Kingdom; e-mail: m.greaves@icr.ac.uk.