To examine the role of the platelet adhesion molecule von Willebrand factor (vWf) in atherogenesis, vWf-deficient mice (vWf−/−) were bred with mice lacking the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR−/−) on a C57BL/6J background. LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were placed on a diet rich in saturated fat and cholesterol for different lengths of time. The atherogenic diet stimulated leukocyte rolling in the mesenteric venules in both genotypes, indicating an increase in P-selectin–mediated adhesion to the endothelium. After 8 weeks on the atherogenic diet, the fatty streaks formed in the aortic sinus of LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice of either sex were 40% smaller and contained fewer monocytes than those in LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice. After 22 weeks on the atherogenic diet (early fibrous plaque stage), the difference in lesion size in the aortic sinus persisted. Interestingly, the lesion distribution in the aortas of LDLR−/−vWf−/− animals was different from that of LDLR−/− vWf+/+ animals. In vWf-positive mice, half of all lesions were located at the branch points of the renal and mesenteric arteries, whereas lesions in this area were not as prominent in the vWf-negative mice. These results indicate that the absence of vWf primarily affects the regions of the aorta with disturbed flow that are prone to atherosclerosis. Thus, vWf may recruit platelets/leukocytes to the lesion in a flow-dependent manner or may be part of the mechano-transduction pathway regulating endothelial response to shear stress.

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (vWf) is a multimeric glycoprotein essential for thrombus formation at high shear stress.1 It is found in plasma, platelet α-granules, Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells, and the subendothelium.2 Even though the involvement of vWf in thrombus formation at the site of atherosclerotic plaque rupture is well established,3 the role of vWf in atherosclerotic lesion development is less clear. Several indications suggest that vWf may directly participate in plaque formation. First, Weibel-Palade bodies are found in great number at the sites of atherosclerotic lesions.4 Second, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and fluid mechanics, 2 factors involved in atherosclerotic lesion development, can induce Weibel-Palade body exocytosis.5,6Third, vWf expression is particularly prominent near branch points and bifurcations, areas prone to atherosclerotic lesion development.7 Fourth, platelets may contribute to the atherosclerotic process by releasing growth factors after their vWf-dependent interaction with a damaged endothelial surface.8,9 Experimental studies performed in pigs with von Willebrand disease (vWd), though supportive of a role for vWf in atherosclerosis,3 have not been conclusive because of the genetic heterogeneity existing among the animals.10

The recent generation of vWf-deficient mice has provided an opportunity to directly test the importance of vWf in atherosclerosis. Because mice are resistant to atherosclerosis, the vWf-deficient mice were first bred with an atherosclerosis-susceptible strain, the LDL receptor (LDLR)-deficient mice (LDLR−/−).11 When fed an atherogenic diet, LDLR−/− mice acquire widespread arterial lesions that progress from simple fatty streaks to complex fibrous plaques over an extended time frame.12 We thus developed a vWd model highly susceptible to atherosclerosis, and our results substantiate an important and complex role for vWf in atherosclerotic lesion development.

Materials and methods

Animals and diets

vWf−/−mice13 were backcrossed 4 times to C57BL/6J and then crossed with LDLR−/−mice on a C57BL/6J background (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Thus, the mice were 5 times backcrossed to the C57BL/6J strain and shared more than 98% of its genetic background. Littermates from the F2 generation of this intercross were genotyped by polymerase chain reaction for LDLR deficiency14 and by Southern blot analysis for vWf deficiency13 and were used to establish LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/− vWf−/− matings. The progeny of these mice were used in our study. Age-matched animals were fed a standard low-fat mouse chow diet containing 5% fat (wt/wt) (Prolab 3000; PMI Feeds, St Louis, MO). When they were 8 weeks old, mice were placed on an atherogenic diet (ICN Biomedicals; Aurora, OH) containing 1.25% (wt/wt) cholesterol, 17.84% (wt/wt) butter, 0.98% (wt/wt) corn oil, and 0.48% (wt/wt) sodium cholate. Experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Center for Blood Research.

Cholesterol determination

Mice were fasted overnight, and blood was collected through the retro-orbital venous plexus. Cholesterol concentrations in plasma were determined using an enzymatic assay kit (Cholesterol kit 352-50; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO).

Intravital microscopy

Mice were injected with 6 g rhodamine (0.2 mg/kg body weight), and a midline abdominal incision was made to expose the mesentery.15 Venules 100 to 200 μm in diameter were recorded for 3 minutes. The number of rolling leukocytes was determined by counting the number of cells passing through a perpendicular plane in 1 minute. Four to 5 vessels for each mouse were recorded, then averaged to determine the number of rolling leukocytes per minute.

Quantification of lesions

Lesions in the aortic sinuses and the aortas, collected between the subclavian and iliac branches, were measured as described.12 To quantify the lesions at the branch points of the renal and mesenteric arteries, arteries were identified and marked on the slide to which the aorta was mounted. Aortas were compared to determine the relative distance of renal and mesenteric arteries region from the top of the aorta (approximately 11 mm). For each measurement, a ruler was placed next to the aorta, and the top was designated as 0 mm. Aortas were stained with Sudan IV, and the surface area between 11 and 15 mm, corresponding to the region marked, was measured using a Leica (Deerfield, IL) Q500MC image analysis program.

Immunohistochemical and histologic analyses

Macrophages and smooth muscle cells in aortic sinus lesions were assessed as described,12 and calcium deposits were determined.16 To quantify cell density in the 8-week lesions, 4 sections for each mouse were stained with hematoxylin, and all nuclei in the lesion areas were counted by light microscopy and divided by the area of the lesion evaluated. We have estimated the number of leukocytes recruited per section by multiplying the density obtained by mean lesion size in that animal. To evaluate P-selectin expression in the lesions, frozen sections of the aortic sinus from mice on atherogenic diet for 4 weeks were fixed in cold acetone for 5 minutes and incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. Slides were then incubated with a goat serum blocking solution (Histostain-SP kit; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA) for 15 minutes, followed by incubation for 1 hour with a rabbit anti–human P-selectin antibody (1:50) that recognizes mouse P-selectin (kindly provided by Dr M. C. Berndt, Baker Medical Research Institute, Melbourne, Australia). A biotinylated second antibody, a horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate, and a substrate-chromogen mixture (Histostain-SP kit; Zymed Laboratories) were added sequentially to visualize the P-selectin.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM using the Studentt test analysis.

Results

Generation of mice with combined vWf and LDLR deficiencies

vWf-deficient mice were crossed with LDLR-deficient mice to generate LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice. Because the mice had been backcrossed 5 times to C57BL/6J and all study mice descended from the same grandparental breeding pair, the colony had minimal genetic variation apart from the vWf genotype. LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice responded similarly to the atherogenic diet, as demonstrated by similar body weights and comparable levels of cholesterol in the blood at all 3 observation times (Table1). Gender was not found to be a significant variable.

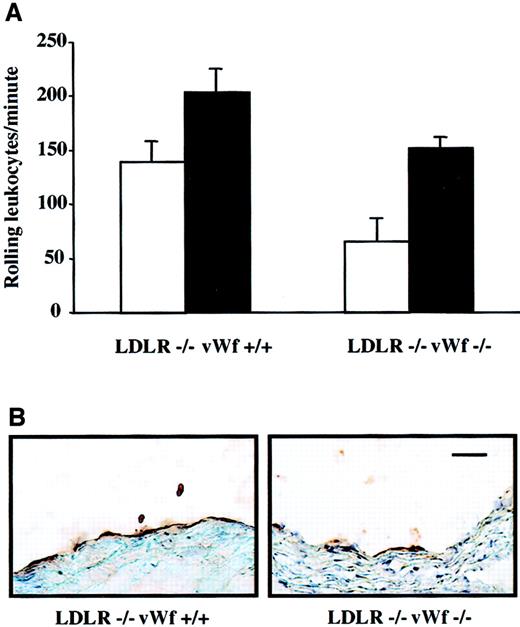

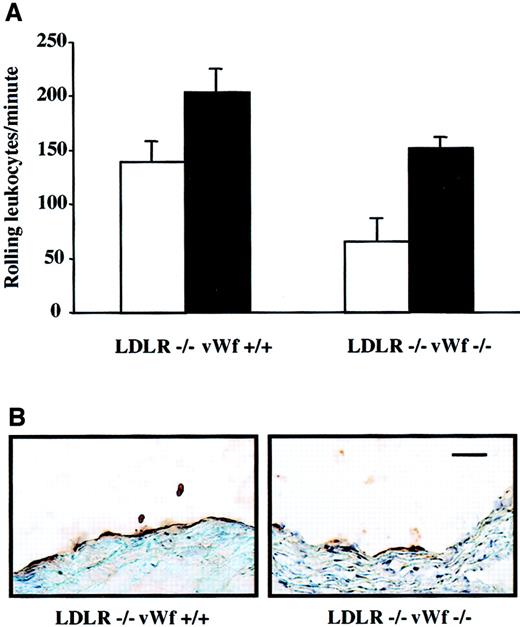

Diet-induced leukocyte rolling

In rabbits, it has been shown that a cholesterol-rich diet induces increased endothelial synthesis not only of vWf17 but also of other adhesion molecules such as P-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.18Because P-selectin is stored in the same storage granules as vWf and plays an important role in atherosclerosis,12,19 we were concerned that its expression on endothelium may be absent in vWf−/− mice. Our laboratory has shown previously that leukocyte rolling in the mesenteric venules of LDLR−/− mice on an atherogenic diet is dependent on P-selectin.12 Similarly, leukocyte rolling on a segment of carotid artery was recently shown to be P-selectin dependent.20 To investigate whether P-selectin expression was induced by the atherogenic diet in our model, we compared leukocyte rolling in LDLR−/− mice with or without vWf. They were fed either mouse chow or an atherogenic diet for 4 weeks and then subjected to intravital microscopy of the mesenteric venules. The atherogenic diet significantly increased the number of rolling leukocytes in both LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice in comparison with the mice maintained on mouse chow (Figure 1A). The number of rolling leukocytes was comparable in the 2 genotypes on the atherogenic diet, but on chow diet fewer leukocytes rolled in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice, as we have also observed in mice deficient in vWf only.21 It is likely that the atherogenic diet, containing cholic acid, increased P-selectin synthesis and direct plasma membrane deposition in both genotypes, making it less dependent on regulated secretion from Weibel-Palade bodies.21Immunohistochemical staining of the aortic sinus of these mice also showed the presence of P-selectin in both genotypes (Figure 1B), though there was less P-selectin in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice. Thus, the absence of vWf reduces, but does not eliminate, P-selectin expression on endothelium.

Effect of vWf deficiency on P-selectin expression.

(A) Leukocyte rolling in LDLR-deficient mice on an atherogenic diet. Four-week-old LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were fed either normal mouse chow (white bars) or atherogenic diet (black bars) for 4 weeks. Animals were injected with 6 g rhodamine, and the mesenteric venules were exposed. The number of leukocytes was quantified by counting the number of cells passing through a perpendicular plane per minute. The atherogenic diet significantly increased rolling in both LDLR−/−vWf+/+ (P = .03) and LDLR−/−vWf−/− (P = .0004) mice (n = 6-9). The number of rolling leukocytes was comparable in the 2 genotypes of mice on atherogenic diet (P = .1). (B) Immunohistochemical staining of the aortic sinus with an anti–P-selectin antibody. Sections were obtained from mice that were on an atherogenic diet for 4 weeks and were stained with a polyclonal antibody against P-selectin. Staining for P-selectin was weaker in mice lacking vWf. Immunohistochemical staining with a PECAM-specific antibody confirmed the integrity of the endothelial monolayer (not shown). Bar = 100 μm.

Effect of vWf deficiency on P-selectin expression.

(A) Leukocyte rolling in LDLR-deficient mice on an atherogenic diet. Four-week-old LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were fed either normal mouse chow (white bars) or atherogenic diet (black bars) for 4 weeks. Animals were injected with 6 g rhodamine, and the mesenteric venules were exposed. The number of leukocytes was quantified by counting the number of cells passing through a perpendicular plane per minute. The atherogenic diet significantly increased rolling in both LDLR−/−vWf+/+ (P = .03) and LDLR−/−vWf−/− (P = .0004) mice (n = 6-9). The number of rolling leukocytes was comparable in the 2 genotypes of mice on atherogenic diet (P = .1). (B) Immunohistochemical staining of the aortic sinus with an anti–P-selectin antibody. Sections were obtained from mice that were on an atherogenic diet for 4 weeks and were stained with a polyclonal antibody against P-selectin. Staining for P-selectin was weaker in mice lacking vWf. Immunohistochemical staining with a PECAM-specific antibody confirmed the integrity of the endothelial monolayer (not shown). Bar = 100 μm.

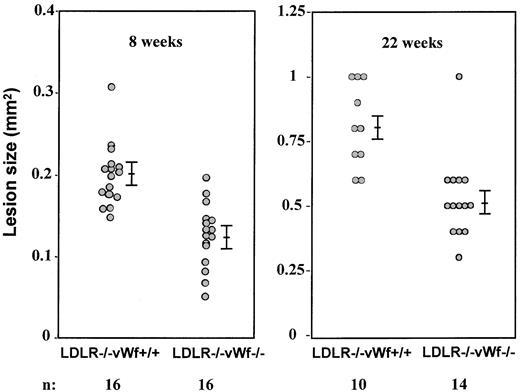

Effect of vWf deficiency on lesion size in the aortic sinus

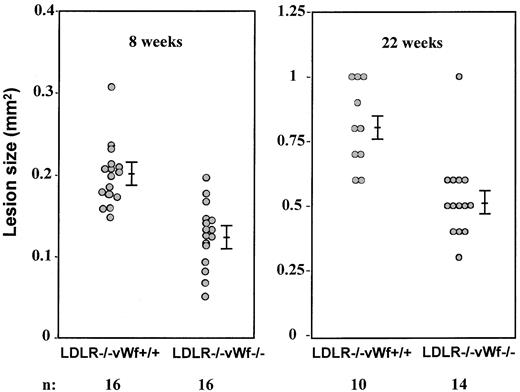

The aortic sinus has been a major focus for qualitative and quantitative studies of atherosclerosis in the mouse because this region is particularly prone to intimal lesion development, and the cusps of the valves provide a useful positional cue in comparative studies of sectioned tissues.22 To quantitatively examine the impact of vWf deficiency on the development of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic sinus, mean lesion areas were measured in oil red-O–stained tissue. All measurements presented in this study were performed blindly to the genotype of the animals. After 8 weeks on the diet, the fatty streak lesions in LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were 40% smaller than in the LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice (0.12 ± 0.01 mm2 vs 0.20 ± 0.01 mm2; n = 16;P = .002; Figure 2). When mean lesion areas of either male or female animals were evaluated, the difference between the LDLR−/−vWf+/+ and LDLR−/− vWf−/− mice was significant, indicating no gender differences in the role of vWf. In mice killed after 22 weeks on the diet, the difference in the early fibrous plaque lesions persisted between the 2 genotypes (0.81 ± 0.05 mm2 for vWf+/+ mice vs 0.53 ± 0.04 mm2 for vWf−/− mice; n = 10-14; P = .0004; Figure 2). However, at 37 weeks—the complex fibrous plaque lesion stage—the absence of vWf no longer affected lesion size (0.84 ± 0.03 mm2 vs 0.85 ± 0.02 mm2, respectively; P = 0.9; n = 10), indicating that vWf does not play an important role in smooth muscle cell recruitment/proliferation in the advanced atherosclerotic lesion.

Size comparison of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic sinus of LDLR-deficient mice with and without vWf.

Eight-week-old mice were put on an atherogenic diet for 8 or 22 weeks. Hearts were collected and processed, and oil red-O–positive lesions were measured. Mean values of 5 sections per mouse were compared. Bars represent standard error of the mean. Differences between LDLR−/− vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were significant at both time points.

Size comparison of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic sinus of LDLR-deficient mice with and without vWf.

Eight-week-old mice were put on an atherogenic diet for 8 or 22 weeks. Hearts were collected and processed, and oil red-O–positive lesions were measured. Mean values of 5 sections per mouse were compared. Bars represent standard error of the mean. Differences between LDLR−/− vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were significant at both time points.

Comparison of aortic sinus lesion composition in the LDLR-deficient mice with and without vWf

As expected for a fatty streak,8 12 the 8-week lesions in both genotypes were composed of CD11b+macrophages engorged with lipids (not shown). We counted the nuclei in hematoxylin-stained lesions at this stage and found that there was no difference in cell density between the 2 genotypes (2320 ± 152/mm2 in LDLR−/− vWf+/+ mice vs 2350 ± 192/mm2 in LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice;P = .7; n = 12-14). However, because the lesions were smaller in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice, the total number of macrophages recruited into the lesions was lower than that in LDLR−/− vWf+/+ mice (288 ± 24 per average lesion section in LDLR−/− vWf−/− mice vs 430 ± 33 in LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice; P = .002; n = 12-14). We found that there were no differences in percentage lesion area positive for α-actin staining in both genotypes after 22 weeks on diet (31% ± 4.9% for LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice vs 29% ± 2.9% for LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice; P = 0.8; n = 8-10). The proportion of smooth muscle cells increased only slightly in the 37-week lesions, remaining similar in the 2 genotypes (P = .6). Thus, the proportion of smooth muscle cells in the lesion was not influenced by vWf. However, after 22 weeks on the diet, fibrous plaque lesions in most of the LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice contained calcification (6 of 10 mice), whereas calcifications were rare in the lesions from LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice (2 of 15 mice). Therefore, the absence of vWf in LDLR−/− mice delayed calcification of the lesions. This difference in calcification persisted at 37 weeks with 80% of LDLR−/−vWf+/+ lesions calcified compared to 47% of LDLR−/−vWf−/− lesions (P < .002).

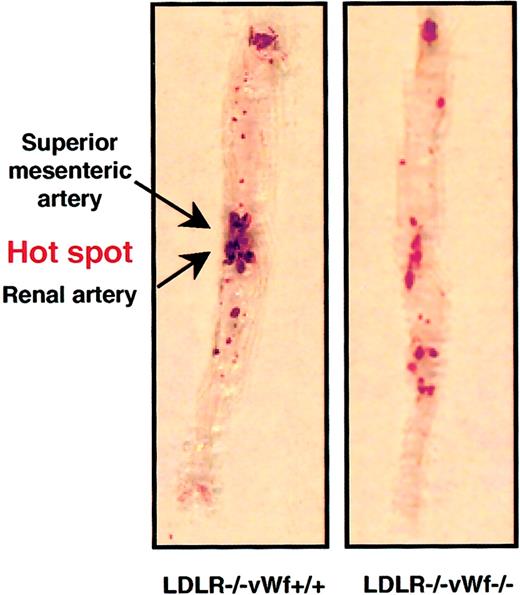

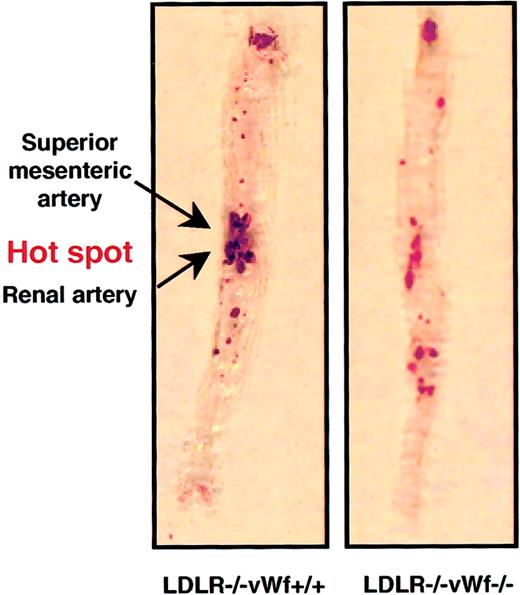

Lesion distribution in the entire aorta

The extent of atherosclerosis was also determined in a large segment of the aorta, from the subclavian branch to the iliac bifurcation. To quantify the lesions, aortas from LDLR−/− vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice were stained with Sudan IV to visualize lipid in the vessel. Unlike the protective effect of vWf deficiency on lesion development in the aortic sinus at 22 weeks (Figure 2), the percentage surface area occupied by the lesions in the rest of the aorta was comparable in the 2 genotypes (Figure3). This was surprising because the extent of lesion formation in the entire aorta usually correlates with lesion size in the aortic sinus,22 an observation also confirmed in all of our previous studies on the role of adhesion molecules in atherosclerosis.12,16 19 On closer inspection, we noticed a difference in the lesion distribution in the aortas between vWf-positive and -negative animals. There was a clear “hot spot” of lesion formation at the branch points of the renal and mesenteric arteries in LDLR−/− vWf+/+ mice. This hot spot was not as prominent relative to the rest of the aorta in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− animals (Figure 3). To evaluate this more objectively, an investigator blinded to the genotype of the animals determined the percentage of lesion located in this portion of the aorta. It was found that approximately half of the lesion areas in LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice were located in this hot spot region, whereas only one third of total lesion area was detected in the same region in LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice. The decreased level of atherosclerosis in the hot spot in the LDLR−/− vWf−/− mice was consistent between the animals—14 of 17 showed a lower percentage of lesions in this region than the mean 48.4% observed in LDLR −/−vWf +/+ mice. This difference in lesion localization was significant (Figure 3). Lesion distribution in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice appeared more diffuse and had a tendency toward an increase in lesion formation outside the hot spot area, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = .09). At 37 weeks, the lesions became prominent in both genotypes. Differences in their distribution could not be discerned because they were distributed uniformly throughout the aortas (50.6% in LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice and 44.3% in LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice;P = .34; n = 11-12). As in the aortic sinus region at this advanced stage, there were no significant differences between the 2 genotypes.

Distribution of atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta of LDLR−/− vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice.

Eight-week-old mice were fed an atherogenic diet for 22 weeks. Aortas were collected between the subclavian and iliac branches and stained with Sudan IV. The area between and around the superior mesenteric artery and renal artery, which is highly prone to lesion formation (see “Materials and methods”) is referred to as the hot spot. The percentage of coverage for LDLR−/− vWf−/− is 16 ± 2.6 and 15.2 ± 1.9, respectively; P = .79. The percentage of the lesion in the hot spot is 48.4 ± 5.4 and 33.7 ± 3.1, respectively; P = .02. Representative specimens from both genotypes are shown, and mean values from 16 to 17 animals of each genotype are given.

Distribution of atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta of LDLR−/− vWf+/+ and LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice.

Eight-week-old mice were fed an atherogenic diet for 22 weeks. Aortas were collected between the subclavian and iliac branches and stained with Sudan IV. The area between and around the superior mesenteric artery and renal artery, which is highly prone to lesion formation (see “Materials and methods”) is referred to as the hot spot. The percentage of coverage for LDLR−/− vWf−/− is 16 ± 2.6 and 15.2 ± 1.9, respectively; P = .79. The percentage of the lesion in the hot spot is 48.4 ± 5.4 and 33.7 ± 3.1, respectively; P = .02. Representative specimens from both genotypes are shown, and mean values from 16 to 17 animals of each genotype are given.

Discussion

A role for vWf in atherosclerosis has long been suspected but was difficult to prove because studies performed with pigs deficient in vWf yielded more questions than answers. The first experimental data suggested that the absence of vWf provided an atheroprotective effect in pigs.23,24 However, it was later shown that the atherogenic diet leads to a variable degree of hypercholesterolemia caused by a polymorphism in apolipoprotein B100,10,25making it difficult to draw a definitive conclusion about the involvement of vWf in atherosclerosis. In contrast, mice deficient in vWf represented a model with a defined genetic background and allowed us to show in the present study that the absence of vWf significantly delays the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in mice on the LDLR-deficient background. The absence of vWf seems to provide a protective effect mainly in regions of disturbed flow, which are highly prone to atherosclerotic lesion development.26,27 The regional importance of vWf for lesion growth distinguishes it from P-selectin, which impacts evenly on lesion development throughout the aorta.12 The slight defect in P-selectin expression in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice on atherogenic diet (Figure 1) could not account for the observed reduction in atherosclerosis. In fact, the protective effect provided by the absence of vWf was much stronger than that of P-selectin because the reduction in lesion size in P-selectin–deficient mice was gender dependent and was only prominent after 8 weeks on the atherogenic diet.12 Although the defect in regulated secretion of P-selectin observed in vWf−/− mice21 likely contributes to reduced atherosclerosis observed in the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice, vWf clearly fulfills additional function(s) in lesion growth. These will be discussed in more detail below.

In the LDLR−/−vWf−/− mice, the fatty streaks in the aortic sinus were smaller than in the LDLR−/−vWf+/+ mice because fewer monocytes were recruited. vWf could participate in the recruitment of monocytes directly or indirectly. Monocytes can adhere to the endothelium by various integrins, such as α4β1, on their surfaces. This integrin has been recently shown to play an important role in the initiation of the atherosclerotic lesion.28 Interestingly, the vWf propolypeptide is a ligand for α4β1.29 The vWf propolypeptide, which is also absent in the vWf-deficient mice, is processed from a large precursor of vWf and stored in the same granules as mature vWf.2 Thus, vWf may participate in the recruitment of monocytes directly through the vWf propolypeptide. vWf may also act indirectly by recruiting platelets9 that, in turn, may facilitate the recruitment of leukocytes.30,31The possibility also remains that the absence of vWf affects the shear stress responses of endothelium. Indeed, shear stress is a modulator of the endothelial cell phenotype.27,32,33 Shear stress regulates endothelial cell gene expression and is thought to be mediated by mechano-transducing receptors.34 vWf is part of the basement membrane to which endothelial cells adhere through their integrin receptors. Integrins can transduce mechanical stimuli to biochemical signals,35 and a blocking antibody to β3 integrin has been shown to affect the shear stress-induced vasodilatation of coronary arteries.36 Therefore, the absence of a major β3 ligand, in this case vWf, might affect the endothelial cell response to shear stress. Our laboratory is addressing the effect of β3 integrin deficiency on atherosclerotic lesion development and lesion distribution.

If vWf is not directly involved in the regulation of endothelial responses to flow, the observed protection seen in vWf−/− mice in early stages of atherosclerosis in regions of disturbed flow could be explained by the unusually flow-sensitive biology of vWf. First, at the molecular level, shear stress induces a conformational transition from globular to extended chain in vWf, as demonstrated by atomic force microscopy.37 This conformational change is likely to expose or mask binding sites for cellular adhesion receptors altering vWf adhesion properties. Second, at the endothelial expression level, laminar shear was shown to induce the secretion of vWf from Weibel-Palade bodies.6 Although this has not yet been examined, changes in shear stress, such as would occur under disturbed flow, may also have such an effect. Mechanosensitive stretch-activated Ca++ channels have been described,38 and, interestingly, Ca++ influx causes the release of Weibel-Palade bodies.39 Third, the cell-cell adhesion processes mediated by vWf are shear dependent. For example, we have shown recently that vWf released from activated endothelial cells in vivo recruited resting platelets to the endothelium in large numbers, preferentially under low shear stress (80-100 seconds−1),9 conditions likely occurring in areas of disturbed flow. This process may deliver platelets and with them leukocytes, specifically to these regions of the aorta. All these possibilities for a shear stress-dependent role of vWf in atherosclerosis are, of course, not mutually exclusive.

Thus, the role of vWf in atherosclerosis appears important but complex. vWf promotes monocyte, and likely platelet, recruitment at the most prominent sites of lesion development. Moreover, the role of vWf in atherosclerosis is not limited to lesion growth. In life-threatening moments, when plaque ruptures, it is only vWf that can form bonds strong enough to lead to a complete occlusion of the vessel,40 41 resulting in myocardial infarction.

We thank Dr Michael A. Gimbrone for critical reading of the manuscript, Lesley Cowan for assistance with its preparation, and Dr Michael C. Berndt for generously providing the rabbit anti–human P-selectin antibody. We also thank Dr Zhao Ming Dong and Allison A. Brown for their help with histologic and morphometric analyses.

Supported by grant R37 HL41002 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Note added in proof

We have now finished analyzing the role of vWf in atherosclerosis in a different mouse model, ie, mice deficient in apoE and fed normal chow. We observed remarkably similar results to those presented above with significant reduction in fibrofatty lesion size in the aortic sinus at 4 months of age (apoE−/−vWf+/+, 0.32 mm2; apoE−/−vWf−/−, 0.15 mm2; n = 10; P < .0001) but no reduction at the later time point of 15 months. Interestingly, at 15 months when lesions spread throughout the aorta, although the surface covered by the lesions was similar in the 2 genotypes (apoE−/−vWf+/+, 28.4 mm2; apoE−/−vWf−/−, 28.3 mm2), the percent lesion found in the “hot spot” was again significantly reduced by the absence of vWf (apoE−/−vWf+/+, 31.2 ± 6.1%; apoE−/−vWf−/−, 16.6 ± 1.6%, n = 11-13,P < .05). Lesions were slightly increased outside the hot spot area, P < .05. Thus, we are persuaded that vWf indeed plays a role in atherosclerotic lesion distribution. We thank Kennard Thomas for help with the analysis.

Author notes

Denisa D. Wagner, The Center for Blood Research, Harvard Medical School, 800 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:wagner@cbr.med.harvard.edu.