Abstract

HIV infection is associated with a high incidence of AIDS-related lymphomas (ARLs). Since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of AIDS-defining illnesses has decreased, leading to a significant improvement in survival of HIV-infected patients. The consequences of HAART use on ARL are under debate. This study compared the incidence and the characteristics of ARL before and after the use of HAART in a large population of HIV-infected patients in the French Hospital Database on HIV (FHDH) and particularly in 3 centers including 145 patients with proven lymphoma. Within the FHDH, the incidence of systemic ARL has decreased between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998, from 86.0 per 10 000 to 42.9 per 10 000 person-years (P < 10−30). The incidence of primary brain lymphoma has also fallen dramatically between the periods, from 27.8 per 10 000 to 9.7 per 10 000 person-years (P < 10−11). The analysis of 145 cases of ARL in 3 hospitals showed that known HIV history was longer in the second period than in the first period among patients with systemic ARL (98 versus 75 months; P < .01). Patients had a higher number of CD4 cells at diagnosis during the second period (191 versus 63/μL, P = 10−3). Survival of patients with systemic ARL also increased between the periods (from 6 to 20 months; P = .004). Therefore, the profile of ARL has changed since the era of HAART, with a lower incidence of systemic and brain ARL. The prognosis of systemic ARL has improved.

Introduction

HIV infection is associated with a high incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The risk of lymphomas is increased approximately 150- to 250-fold among HIV-infected patients compared with the general population.1 Lymphomas are categorized among the AIDS-defining conditions.2 Since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of opportunistic infections has decreased, so lymphoma is now by far the most lethal complication of AIDS.3 The risk factors for AIDS-related lymphomas (ARLs) are older age,4 severe immunodeficiency,5 and prolonged HIV infection.6

Most ARLs are high-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. This group comprises different pathologic subtypes of lymphomas, also occurring in immunocompetent patients, mostly represented by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and Burkitt lymphoma (BL).7-9 Before the use of HAART, relations between the types of ARL and the characteristics of HIV disease had been shown. Patients with DLBCL have a significantly higher rate of previous AIDS disease as well as a lower CD4 cell count at diagnosis of ARL than patients with BL.10,11 Moreover, 2 rare categories of ARL, such as plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity12 and primary effusion lymphoma,13 occur more specifically in HIV infection.

ARL displays a marked capacity to involve extranodal sites, in particular the central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and bone marrow. The most frequent extranodal localization is primary brain lymphomas (PBLs). These belong to the DLBCL category and are associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in almost all cases.14,15 PBL is associated with severe immunosuppression, a very low number of CD4 cells (less than 50/μL), and a poor median survival (4 months).7 Patients with systemic ARL have advanced clinical stages with frequent bone marrow or liver involvement and bulky tumor size at presentation, with a high level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). These systemic ARLs also have a poor prognosis.7

Since the wide use of HAART, the incidence of most AIDS-defining illnesses has decreased dramatically, leading to a much longer survival of patients.16,17 The incidence rates ofPneumocystis carinii pneumonia, cytomegalovirus infection, and Candida esophagitis during 1996 and 1997 declined from 27.4 per 100 person-years to 6.9 per 100 person-years.18Furthermore, the incidence of PBL has also been shown to decrease in several studies.18-20 The consequences of HAART use on systemic ARL are more controversial.20-26

Our goal was to analyze the evolution of the incidence and characteristics of ARL since the use of HAART in a large population of HIV-infected patients in the French Hospital Database on HIV (FHDH; for participants, see “”) and in an exhaustive cohort of patients.

Patients and methods

In the first part of the analysis, incidence trends were analyzed from the FHDH. This is a clinical epidemiologic network started in 1989 that includes, to date, epidemiologic information provided by 29 centers that are especially involved in the medical care of HIV-infected persons at 68 French university hospitals. To date, more than 80 000 patients with HIV infection are included in the FHDH. The current study includes all patients aged at least 15 years with an initial ARL episode during 2 periods (before and after the use of HAART). The first period chosen was 1993-1994 and the second period was 1997-1998. Numbers of person-years at risk for systemic ARL were 48 254 for the first period and 66 376 for the second period. Numbers of person-years at risk for PBL were 48 571 for the first period and 66 972 for the second period. An analysis of incidence stratified on CD4 count was performed among this population.

The second part of the analysis was based on an exhaustive analysis of cases with a review of patient charts. This was performed in 3 hospitals in Paris (Rothschild, Pitié-Salpétrière, and Pasteur hospitals). These 3 hospitals were chosen because they are major centers for the care of HIV-infected patients in Paris. Case lists for each of these 3 hospitals were collected from the FHDH. To be as exhaustive as possible, these lists were compared and when necessary completed by cases recorded in the pathology departments of these 3 hospitals and by clinicians. For each case, the clinical chart was reviewed to confirm the diagnosis and to collect data. All pathology reports were reviewed by 2 expert hematopathologists. Cases with no pathologic proof of ARL were excluded. However, 2 cases of PBL diagnosed on the basis of typical imaging features and a positive EBV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were retained.27 Cases occurring among patients who were not followed in these 3 hospitals were excluded. Data concerning demographics, clinical and biologic aspects of HIV infection, HIV treatment, ARL characterization, ARL treatment, and evolution were collected from the clinical chart. HIV viral load assays were available for 44 of 47 patients during the second period.

Comparisons between patients were analyzed with the Studentt test, Fisher exact test, Mann-Whitney test, or χ2 test when appropriate. Survival time was calculated from the diagnosis to death or to the date when the patient was last seen. Survival was estimated with Kaplan-Meier estimates. Comparisons of survival were analyzed by using the log-rank test. The significance level used was 5%. Statistical analysis used the Epi-Info (version 6) and SAS computer programs (version 6.12; Cary, NC).

Results

Incidence estimates from the FHDH

Among the FHDH cohort, the incidence of ARL fell between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998. The incidence of systemic ARL decreased from 86.0 per 10 000 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI], 77.7-94.3) during the first period to 42.9 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI, 38.0-47.9) during the second period (P < 10−30) (Table1). The decrease in incidence was more important for PBL: from 27.8 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI, 23.1-31.2) to 9.7 per 10 000 person-years (95% CI, 7.3-11.2) (P < 10−11) (Table2). The risk of both types of ARL did not change between the periods among patients with similar CD4 cell counts (Tables 1 and 2). In both periods, the incidence of systemic ARL was lowest among patients with a CD4 count greater than 350/μL (15.8 per 10 000) and highest among patients with a CD4 count lower than 50/μL (247.1 per 10 000). During the same periods, the incidence of PBL was 1.5 per 10 000 among patients whose CD4 count was greater than 350/μL and 96.9 per 10 000 among patients with a CD4 count lower than 50/μL. Meanwhile, the proportion of patients at risk of ARL with low CD4 cell counts (less than 200/μL) decreased between the periods, from 49.5% to 24.5%.

Characteristics of the patients in the 3 hospitals

The study population included 145 patients. The proportion of men was 91.7% (versus 74.6% in the FHDH). The median age of the whole population was 39 years (range, 23-74 years). The main transmission group was homosexual men (61%, versus 35.5% in the FHDH). The number of cases of ARL fell between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998, from 98 cases during the first period to 47 cases during the second period. Forty patients (28%) had PBL and 105 (72%) had systemic ARL. The number of cases of systemic ARL decreased from 63 to 42. The decrease in the number of cases was much greater for PBL than for systemic ARL. Thirty-five cases of PBL were observed during the first period compared with only 5 during the second period.

Comparison of characteristics of patients with systemic ARL between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998 in the 3 hospitals

Differences between the periods were analyzed separately for PBL and systemic ARL. Comparisons among patients with systemic ARL are shown in Table 3. No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed between the periods. Only 2 patients during the first period and 3 patients during the second period were diagnosed with HIV infection after the diagnosis of ARL was made. Among patients diagnosed with HIV before the occurrence of ARL, the natural history of HIV infection differed between the periods. The duration since the diagnosis of HIV infection was significantly longer during the second period than during the first period (median 98 versus 75 months; P = .014). The CD4 cell count was significantly higher in the second period than in the first period (median 191/μL versus 63 /μL; P = .002). During the second period, viral load was measured at diagnosis in 39 patients; the median viral load was 29 000 copies per liter. Four patients had a viral load below the detection limit. The proportions of patients who had had antiretroviral therapy before the diagnosis of ARL were similar in the 2 periods (84% and 72%; P = .181). However, duration since the first antiretroviral therapy was significantly longer during the second period than during the first period (median, 44 versus 31 months; P = .034). Sixty-four percent of patients during the second period had received HAART before the diagnosis of ARL. The mean time since the first prescription of HAART was 10 months.

Review of the pathology reports showed that among cases of systemic ARL, 72 were DLBCL (72.8%), 22 were BL (21.4%), 6 were polymorphic lymphoid proliferation (5.8%), and 2 cases could not be classified. CD4 cell count was significantly higher among cases of BL than among cases of DLBCL (median, 195/μL versus 66/μL;P = .005). The proportions of cases with extranodal localization did not differ between cases of BL and cases of DLBCL (81.8% and 77.3%; P = .87). The proportion of patients for whom ARL was the first AIDS disease was significantly higher among patients with BL than among patients with DLBCL (73% versus 49%;P = .05). The proportion of patients with DLBCL tended to decrease between the periods, from 79% to 63%, in comparison with cases of BL (P = .17).

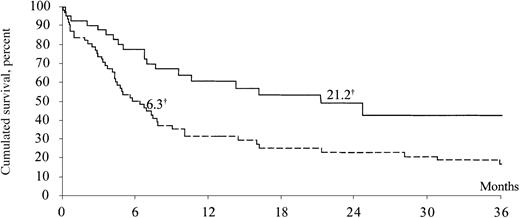

The proportion of patients with an extranodal localization of ARL tended to decrease between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998, from 84% to 69% (P = .067). Disease-stage distributions were similar in the 2 periods. A raised LDH level was observed in the same percentage of patients in the 2 periods (42%). Median survival increased significantly from 6.3 months in the first period to 21.2 months in the second period (P = .004) (Figure1). The treatment of systemic ARL during both periods was extremely heterogeneous. During the first period, 48 patients received various regimens of polychemotherapy (eg, CHOP, ACVBP), 3 patients received only corticosteroids, 1 patient received irradiation, and 5 patients had no treatment; 6 had missing data. During the second period, 33 patients received various regimens of polychemotherapy (eg, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone [CHOP]; adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, bleomycin, prednisone [ACVBP]; cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide [CDE]) and 3 patients did not have any specific treatment; 6 had missing data. Concerning the treatment of HIV infection during the course of ARL, the proportion of patients who received antiretroviral therapy increased greatly from 41% in the first period to 100% in the second period (P < 10−6). Among patients with a known cause of death, ARL was the main cause of death in 88% of cases in the first period and 86% in the second period.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival of patients with systemic AIDS-related lymphoma between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998 in 3 French hospitals.

Dotted line represents the 1993-1994 period (n = 63); solid line, 1997-1998 (n = 42), for 105 patients total; †, median survival (months). Log-rank test: P = .004.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival of patients with systemic AIDS-related lymphoma between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998 in 3 French hospitals.

Dotted line represents the 1993-1994 period (n = 63); solid line, 1997-1998 (n = 42), for 105 patients total; †, median survival (months). Log-rank test: P = .004.

Primary brain lymphoma

No change in demographic characteristics was noticed between 1993-1994 and 1997-1998 (Table 4). All cases of PBL were DLBCL in both periods. All patients with PBL had already been diagnosed with HIV infection before the diagnosis of ARL. The duration since diagnosis of HIV infection was significantly longer during the second period than during the first (111 versus 79 months; P = .023). PBL was the first AIDS-defining illness for 2 patients in the second period and 6 patients in the first period. Four of the 5 patients diagnosed with PBL during the second period had less than 20 CD4 cells/μL, and one had 229 CD4 cells/μL. All of them had a viral load of greater than 40 000 copies/L, and all had been treated with HAART. The median time since the beginning of antiretroviral treatment was 46 months in the second period versus 35 months in the first period (P = not significant). The treatment of PBL during the first period was heterogeneous, including irradiation (14 patients), irradiation and chemotherapy (2 patients), intravenous (IV) methotrexate (4 patients), corticoids (4 patients), and no treatment (3 patients); 8 had missing data. In the second period, treatment of PBL was IV methotrexate for 4 patients; the fifth patient did not receive any treatment. The median survival did not change significantly between the periods (2.2 and 2.6 months; data not shown).

Discussion

The incidence of systemic ARL has fallen from 86.0 per 10 000 person-years in 1993-1994 to 42.9 per 10 000 person-years in 1997-1998 (P < 10−30). This decrease has been particularly important for PBL, which has almost disappeared since the use of HAART. However, the incidence rates of systemic ARL and of PBL by strata of patients with similar CD4 cell counts did not decrease between the periods. It is the decrease in the proportion of patients with low CD4 counts (less than 200/μL) that may explain the diminution in the incidence of PBL and systemic ARL. Classic differences between PBL and systemic ARL have been confirmed, showing that patients with PBL have a longer duration of AIDS, a lower lymphocyte count, a lower CD4 count, and a shorter survival than patients with systemic ARL. Comparison of characteristics of cases of systemic ARL between the periods shows that HIV history was longer in the second period than in the first period. Patients had a higher number of CD4 cells at diagnosis during the second period. No significant change in pathologic distribution of cases was observed between the periods. Survival of patients with systemic ARL also increased significantly between the periods.

The first evidence of the efficacy of a protease inhibitor (ritonavir) in the treatment of HIV-infected patients was published in 1995.28 Reports on the efficacy of HAART were published in 1996,29 and guidelines concerning HAART use were published in 1997.30 Therefore, we chose to compare the period before this “discovery” (1993-1994) with the period following the publication of guidelines (1997-1998). Incidence trends were compared within the FHDH and exhaustively among all the patients with ARL during the 2 periods in 3 different hospitals. All of the charts of these patients were reviewed to limit reporting biases. The high proportions of men and of homosexual or bisexual transmission among these 3 hospitals reflect the characteristics of HIV epidemics in Paris. These 3 hospitals are major centers for up-to-date care of HIV-infected patients. Therefore, the trends we observe among these patients reflect well the recent changes in HIV infection therapy.

The overall incidence rates of PBL and systemic ARL decreased dramatically between the periods. However, after stratification on CD4 cell count, the incidences did not change between the periods. The proportion of patients with low CD4 count has greatly decreased between the periods. This diminution in the proportion of patients at high risk of lymphoma (low CD4 cell count) has led to a drastic decrease in the overall incidence of lymphoma. The changes in the CD4 count distribution among patients at risk between the periods also led to a higher median CD4 count among patients with lymphoma.

The diminution in incidence of systemic ARL observed in our population from 3 hospitals was confirmed in the FHDH, which is one of the most important cohorts of HIV-infected patients. Several studies have already tried to answer the question of the evolution of systemic ARL, but conclusions were controversial.20-26 A recent report from 23 prospective studies of HIV-infected patients also showed a significantly decreasing incidence of ARL (from 62 per 10 000 to 36 per 10 000 person-years; P < .0001). This decrease included both PBL and immunoblastic systemic ARL.20 Some other studies may have been limited by the choice of time periods too early after HAART20,21 or by a small number of cases.22 The study of the incidence of ARL among the patients followed in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study may have been limited because all patients had been diagnosed with HIV infection between 1984 and 1985, and therefore could not reflect the whole HIV-infected population.23 Our conclusions differ from those reported in recent articles in Blood.24,25However, the analysis of the incidence of systemic ARL reported by Matthews et al24 showed a nonsignificant decreasing trend from 72 per 10 000 to 32 per 10 000 person-years from 1991 to 1998. In their study, the number of incident cases since 1996 was probably too small to reach significant conclusions. The differences between our conclusions and those of Levine et al25 may be explained by differences in the studied populations.

A better survival estimate was found among patients with systemic ARL during the second period of our study. The increased survival we found may be explained by a different distribution of prognostic factors between these periods. Poor prognostic factors include poor performance status, prior AIDS disease, IB subtype, low CD4 cell count, longer duration since HIV infection, and international prognostic index.6,31,32 Indeed, the proportions of 2 well-known poor prognostic factors changed between the periods: CD4 cell count at diagnosis increased and the proportion of patients with a prior AIDS diagnosis decreased between the periods. Moreover, Matthews et al24 also showed an improvement in survival, although nonsignificant. Our results differ from those reported by Levine et al,25 who found no improvement in survival since 1982, but they also showed a lower median CD4 cell count since 1995 among their study population. Because the treatments of ARL were extremely heterogeneous in both periods, no specific interpretation can be deduced from the analysis of treatment. The literature does not support the hypothesis that supportive therapy of non-Hodgkin lymphoma has progressed significantly since 1993. In our series of patients, we do not have data on supportive therapy to reinforce this hypothesis. However, the proportion of patients who received antiretroviral therapy increased from 41% to 100% between the periods, and this may have an effect on survival.

Our study confirms a strong decrease in the incidence of PBL since the use of HAART. We chose to retain only biopsy-proven cases, except for 2 cases with both a typical imaging aspect and a positive EBV PCR result in the CSF. During the first period, many patients with probable PBL were excluded from the population because of the absence of proof of PBL. During the second period, no patient was excluded for this reason. Therefore, PBL incidence might be underestimated during the first period. It is noteworthy that Levine et al25 reported a steady incidence of PBL since 1982. Their report is the first to show no decrease in PBL incidence since the use of HAART, in contrast to several studies, including the large epidemiologic collaborative study that was reported recently.18-20 The restoration of immunity is probably the key explanation for the lower incidence of PBL since HAART. Restoration of the blood-brain barrier might also explain the lower incidence of PBL. The lower incidence of neurologic complications of AIDS might also limit the disruptions of this barrier and therefore might play a role in the decreasing incidence of PBL.

In conclusion, our study shows that the profile of ARL has changed dramatically since the era of HAART, with a drastic decrease in the incidence of PBL and a much lower incidence of systemic ARL. Comparison of characteristics of cases of systemic ARL shows a longer HIV infection duration in the second period than in the first period. Patients also had a higher CD4 cell count at ARL diagnosis. The prognosis of ARL has improved, with a median survival at least 3 times longer since HAART than before. The frequency of the association with EBV in the context of immune restoration must be further studied.

Clinical Epidemiology Group of the FHDH

Scientific committee:

Dr S. Alfandari, Dr F. Bastides, Dr E. Billaud, Dr A. Boibieux, Pr F. Boué, Pr F. Bricaire, D. Costagliola, Dr L. Cotte, Dr L. Cuzin, Pr F. Dabis, Dr S. Fournier, Dr J. Gasnault, Dr C. Gaud, Dr J. Gilquin, Dr S. Grabar, Dr D. Lacoste, Pr J. M. Lang, Dr H. Laurichesse, Pr C. Leport, M. Mary-Krause, Dr S. Matheron, Pr M. C. Meyohas, Dr C. Michelet, Dr J. Moreau, Dr G. Pialoux, Dr I. Poizot-Martin, Dr C. Pradier, Dr C. Rabaud, Pr E. Rouveix, Pr P. Saı̈ag, Pr D. Salmon-Ceron, Pr J. Soubeyrand, Dr H. Tissot-Dupont.

Dossier Médical Informatisé (DMI2) coordinating center:

French Ministry of Health (Dr B. Haury, S. Courtial-Destembert, G. Leblanc).

Statistical Data Analysis Centre:

INSERM SC4 (Dr S. Abgrall, Dr S. Benoliel, D. Costagliola, Dr S. Grabar, L. Lièvre, M. Mary-Krause).

Centre d' Information et de Soin sur l' Immunodeficience Humaine (CISIH):

Paris area: CISIH de Bichat-Claude Bernard (Hôpital Bichat-Claude Bernard: Dr S. Matheron, Pr J. P. Coulaud, Pr J. L. Vildé, Pr C. Leport, Pr P. Yeni, Pr E. Bouvet, Dr C. Gaudebout, Pr B. Crickx, Dr C. Picard-Dahan), CISIH de Paris-Centre (Hôpital Broussais: Pr L. Weiss, Dr D. Aureillard; GH Tarnier-Cochin: Pr D. Sicard, Pr D. Salmon; Hôpital Saint-Joseph: Dr J. Gilquin, Dr I. Auperin), CISIH de Paris-Ouest (Hôpital Necker Adultes: Dr J. P. Viard; Hôpital Laennec: Dr W. Lowenstein; Hôpital de l'Institut Pasteur), CISIH de Paris-Sud (Hôpital Antoine Béclère: Pr F. Boué, Dr R. Fior; Hôpital de Bicêtre: Dr C. Goujard, Dr C. Rousseau; Hôpital Henri Mondor; Hôpital Paul Brousse), CISIH de Paris-Est (Hôpital Rothschild: Pr W. Rozenbaum, Dr C. Maslo; Hôpital Saint-Antoine: Pr M. C. Meyohas, Dr J. L. Meynard, Dr O. Picard, N. Desplanque; Hôpital Tenon: Pr J. Cadranel, Pr C. Mayaud), CISIH de Pitié-Salpétrière (GH Pitié-Salpétrière: Pr F. Bricaire, Pr C. Katlama), CISIH de Saint-Louis (Hôpital Saint-Louis: Pr J. M. Decazes, Pr J. M. Molina, Dr L. Gerard; GH Lariboisière-Fernand Widal: Dr J. M. Salord, Dr Diermer), CISIH 92 (Hôpital Ambroise Paré: Dr C. Dupont, H. Berthé, Pr P. Saı̈ag; Hôpital Louis Mourier (Dr C. Michon, C. Chandemerle; Hôpital Raymond Poincaré: Dr P. de Truchis), CISIH 93 (Hôpital Avicenne: Dr M. Bentata, P. Berlureau; Hôpital Jean Verdier: J. Franchi, Dr V. Jeantils; Hôpital Delafontaine: Dr Mechali, B. Taverne).

Outside Paris area:

CISIH Auvergne-Loire (CHU de Clermont-Ferrand: Dr H. Laurichesse, Dr F. Gourdon; CHRU de Saint-Etienne: Pr F. Lucht, Dr A. Fresard); CISIH de Bourgogne-Franche Comté (CHRU de Besançon; CHRU de Dijon; CH de Belfort: Dr J. P. Faller, P. Eglinger); CISIH de Caen (CHRU de Caen: Pr C. Bazin, Dr R. Verdon), CISIH de Grenoble (CHU de Grenoble), CISIH de Lyon (Hôpital de la Croix-Rousse; Hôpital Edouard Herriot: Pr J. L. Touraine, Dr T. Saint-Marc; Hôtel-Dieu; CH de Lyon-Sud: Médecine Pénitentiaire), CISIH de Marseille (Hôpital de la Conception: Dr I. Ravaux, Dr H. Tissot-Dupont; Hôpital Houphouët-Boigny: Dr J. Moreau; Institut Paoli Calmettes; Hôpital Sainte-Marguerite: Pr J. A. Gastaut, Dr I. Poizot-Martin, Pr J. Soubeyrand, Dr F. Retornaz; Hotel-Dieu; CHG d'Aix-En-Provence; Centre Pénitentiaire des Baumettes; CH d'Arles; CH d'Avignon: Dr G. Lepeu; CH de Digne Les Bains: Dr P. Granet-Brunello; CH de Gap: Dr L. Pelissier, Dr J. P. Esterni; CH de Martigues: Dr M. Nezri, Dr Y. Ruer, CHI de Toulon), CISIH de Montpellier (CHU de Montpellier: Pr J. Reynes; CHG de Nı̂mes), CISIH de Nancy (Hôpital de Brabois: Pr T. May, Dr C. Rabaud), CISIH de Nantes (CHRU de Nantes: Pr F. Raffi, Dr M. F. Charonnat), CISIH de Nice (Hôpital Archet 1: Dr C. Pradier, Dr P. Pugliese; CHG Antibes Juan les Pins), CISIH de Rennes (CHU de Rennes: Pr C. Michelet, Dr C. Arvieux), CISIH de Rouen (CHRU de Rouen: Pr F. Caron, Dr Y. Debas), CISIH de Strasbourg (CHRU de Strasbourg: Pr J. M. Lang, Dr D. Rey, Dr P. Fraisse; CH de Mulhouse), CISIH de Toulouse (CHU Purpan: M. Perez, F. Balsarin, Pr E. Arlet-Suau, Dr M. F. Thiercelin Legrand; Hôpital la Grave; CHU Rangueil), CISIH de Tourcoing-Lille (CH Gustave Dron; CH de Tourcoing: Dr S. Alfandari, Dr Y. Yasdanpanah), CISIH de Tours (CHRU de Tours; CHU Trousseau).

Overseas:

CISIH de Guadeloupe (CHRU de Pointe-à-Pitre), CISIH de Guyane (CHG de Cayenne: Dr M. Sobesky, Dr R. Pradinaud), CISIH de Martinique (CHRU de Fort-de-France), CISIH de La Réunion (CHD Félix Guyon: Dr C. Gaud, Dr M. Contant).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Caroline Besson, Service d'Hématologie Adultes, Hôpital Necker, 149 rue de Sèvres, 75743 Paris Cédex 15, France; e-mail:caroline.besson@nck.ap-hop-paris.fr.