Mutations in the perforin gene have been described in some patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), but the role of perforin defects in the pathogenesis of HLH remains unclear. Four-color flow cytometric analysis was used to establish normal patterns of perforin expression for control subjects of all ages, and patterns of perforin staining in cytotoxic lymphocytes (natural killer [NK] cells, CD8+ T cells, CD56+ T cells) from patients with HLH and their family members were studied. Eleven unrelated HLH patients and 19 family members were analyzed prospectively. Four of the 7 patients with primary HLH showed lack of intracellular perforin in all cytotoxic cell types. All 4 patients showed mutations in the perforin gene. Their parents, obligate carriers of perforin mutations, had abnormal perforin-staining patterns. Analysis of cytotoxic cells from the other 3 patients with primary HLH and remaining family members had normal percentages of perforin-positive cytotoxic cells. On the other hand, the 4 patients with Epstein-Barr virus–associated HLH typically had depressed numbers of NK cells but markedly increased proportions of CD8+ T cells with perforin expression. Four-color flow cytometry provides diagnostic information that, in conjunction with evidence of reduced NK function, may speed the identification of life-threatening HLH in some families and direct further genetic studies of the syndrome.

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening immune disorder characterized by fever, massive hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, and, frequently, seizures.1Historically HLH has been categorized clinically as primary or secondary. The primary form, known as familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL), typically shows symptomatic presentation in infancy and has an autosomal-recessive inheritance. The secondary form is usually associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, and may become apparent at an older age.

Regardless of which form is suspected, therapy with immunosuppressive agents is addressed at the severity of symptoms (according to HLH-94 treatment protocol).2 In patients with FHL, bone marrow transplantation is highly recommended before central nervous system involvement advances. However, it has been extremely difficult to distinguish the primary and secondary forms of HLH by clinical symptoms, documented infection, or clinical course unless families have had more than one child with HLH. Even if the disease has been triggered by EBV, it may still be FHL.

Recently, mutations in the perforin gene have been described in some patients with HLH.3 This evidence suggests that defective or deficient perforin may be one of the causes of this disease. Perforin is a membranolytic protein that is expressed in the cytoplasmic granules of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells. Perforin is believed to be principally responsible for the translocation of granzyme B from cytotoxic cells into target cells; the granzyme B then migrates to the target cell nucleus to participate in triggering apoptosis.4 The roles of perforin in immune regulation still have not been well defined. However, it is easily conceivable that without perforin, cytotoxic T cells and NK cells show reduced or no cytolytic effect on target cells; this offers an explanation of why patients with HLH have markedly decreased or absent NK- cell function.

The objectives of our work were to validate a rapid technique for the measurement of perforin in cytotoxic human lymphocytes, to establish normal patterns of perforin staining in control subjects of different ages, and to study the pattern of perforin staining in HLH patients with and without mutation in the perforin genes, in their family members, and in patients with other disorders with life-threatening hemophagocytic complications.

Patients, materials, and methods

Pediatric control samples

To establish an age-dependent normal range, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid peripheral blood was obtained from residual complete blood count (CBC) samples from an outpatient clinic at Children's Hospital Medical Center in Cincinnati under an agreement approved by its Institutional Review Board (IRB). The samples were delivered anonymously, identified by the age and gender of the patient, and with the result of the CBC provided. Those samples with CBC or differential parameters outside of the normal range for age were excluded from the study and discarded. All samples were held at room temperature and processed within 24 hours of collection.

Patient and family member samples

Samples coming to the Children's Hospital Hematology/Oncology lab for NK-cell function testing to rule out HLH were screened for perforin expression when requested by the referring physician by prior telephone consultation. A diagnosis of HLH was either confirmed or dismissed in each case by the referring institution. EBV status was also obtained from the referring institution. For cases of confirmed familial or secondary HLH, samples from the family members were subsequently obtained after obtaining informed consent under an IRB-approved study of HLH family members that has been in effect since 1998.

Perforin staining

Whole blood was first surface stained with the following antibodies: T-cell receptor αβ (TCRαβ)–fluorescein isothiocyanate, CD8-PerCP (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA), and CD56-APC (Immunotech, Brea, CA) for 20 minutes at room temperature. Red cells were then lysed for 10 minutes with 2 mL of FACSlyse (BD Immunocytometry Systems) and washed. The resultant white cell pellet was then permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and stained with either phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated antiperforin or PE-conjugated mouse IgG2b (BD Pharmingen) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing, cells were resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Normal ranges for age-matched controls have been developed by studying 80 healthy individuals ranging from 1 month to 50 years of age, of which 41 were under 16 years of age.

Flow cytometric analysis

Samples were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The following gates were used to distinguish the 3 populations of interest: CD8+ T cells were defined as being TCRαβ+, CD8+, and CD56−; NK cells were defined as being TCRαβ− and CD56+; CD56+ T cells were defined as being TCRαβ+ and CD56+. All populations were also restricted to a lymphocyte gate based on forward versus side scatter. The perforin-positive region was set using an isotype-matched negative control, and the percent positive for each region was reported.

Detection of perforin mutation

DNA was prepared from EBV-infected cell lines using standard methods. The coding region of the perforin gene was polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified from exon 2 and exon 3. Primers used for amplification were as follows: for exon 2, forward (F2) 5′-CCCTTCCATGTGCCCTGATAATC-3′ and reverse (R2) 5′-AAGCAGCCTCCAAGT-TTGATTG-3′, and for exon 3, forward (F3) 5′-CCAGTCCTAGTTCTGCCCACTTAC-3′ and reverse (R3) 5′-GAACCCCTTCAGTCCAAGCATAC-3′. Direct DNA sequence analysis was performed using the ABI Prism 3700 Sequence Detection System (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with the same primer pairs used for PCR amplification.

Results

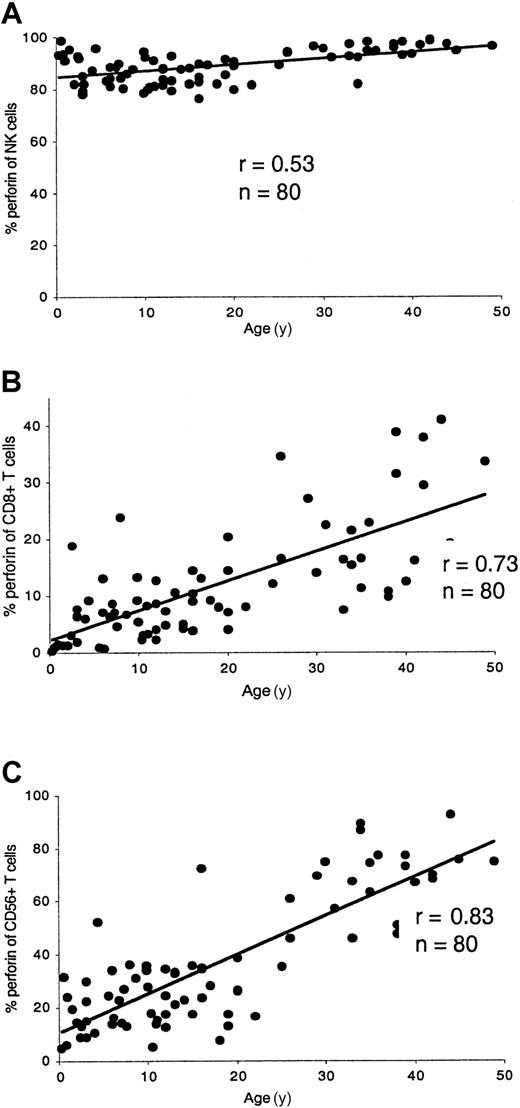

The technique described here has proved to be rapid and reproducible. The proportion of perforin-expressing cytotoxic lymphocytes was age related (Figure 1). The percentage of NK cells staining with antiperforin antibody was rather constant as age increased. In children (1-15 years) the proportion of perforin-expressing NK cells was 86% ± 5% compared to 92% ± 6% in adults (> 15 years). Perforin-containing CD8+ T cells increased with age. In young children, especially in infants, the proportion of perforin-expressing CD8+ T cells was very low. In children the perforin expression of CD8+ T cells was 7% ± 5% compared to 18% ± 10% in adults. Perforin-containing CD56+ T cells also increased with age. In children the proportion of CD56+ T cells expressing perforin was 23% ± 10% compared to 54% ± 23% in adult controls. A characteristic perforin-staining pattern for a healthy adult is shown in Figure 2A.

Age-related perforin expression in cytotoxic lymphocytes.

The percentage of perforin in NK cells (A) was rather constant as age increased. Perforin-containing CD8+ T cells (B) increased with age. In young children, especially in infants, the perforin content of CD8+ T cells was very low. Perforin-containing CD56+ T cells (C) also increased with age.

Age-related perforin expression in cytotoxic lymphocytes.

The percentage of perforin in NK cells (A) was rather constant as age increased. Perforin-containing CD8+ T cells (B) increased with age. In young children, especially in infants, the perforin content of CD8+ T cells was very low. Perforin-containing CD56+ T cells (C) also increased with age.

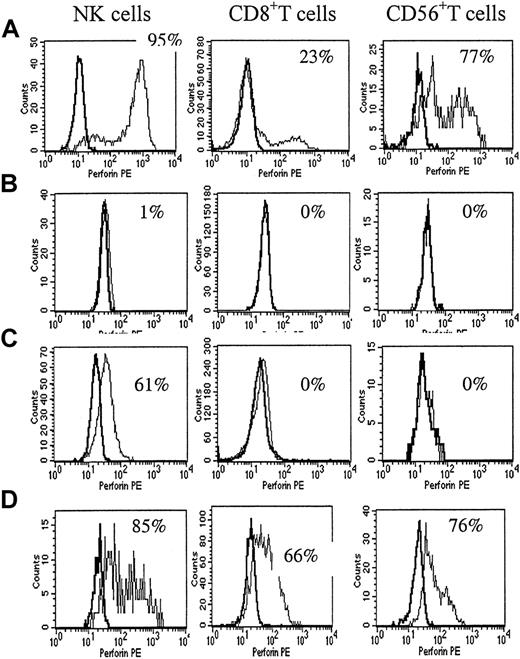

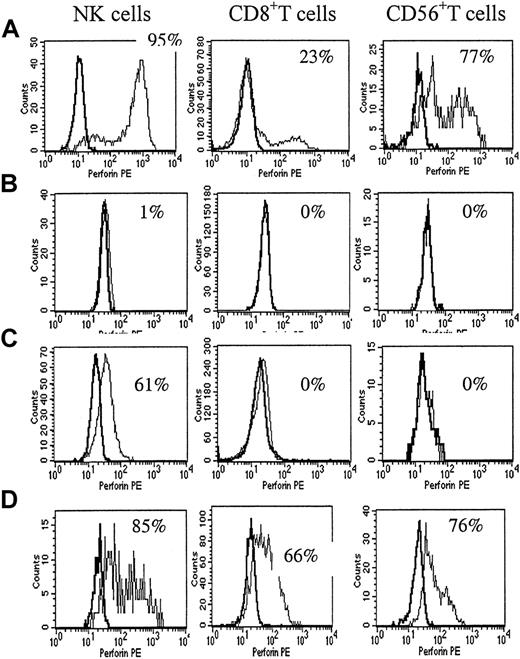

The perforin-staining pattern in a healthy control and in patients with HLH.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of perforin expression in blood cytotoxic cells from a healthy adult. A normal percentage of perforin expression in NK cells in adults was 92% ± 6%. In CD8+ T cells, it was 8% to 28% in adults. In CD56+ T cells, it was 30% to 77% in adults. (B) The most complete perforin deficiency was seen in patient P1 with primary HLH. The perforin-staining pattern showed no difference from the isotype control in all cell types. (C) The partial perforin deficiency was seen in patient P10 with primary HLH. The perforin positivity in NK cells was moderately decreased and the perforin positivity in CD8+ and CD56+ T cells was extremely decreased. (D) The percentage of NK cells in P3, a patient with EBV-associated HLH, was 3%, and NK function was extremely decreased. The perforin positivity was markedly increased in CD8+ and CD56+ T cells.

The perforin-staining pattern in a healthy control and in patients with HLH.

(A) Flow cytometric analysis of perforin expression in blood cytotoxic cells from a healthy adult. A normal percentage of perforin expression in NK cells in adults was 92% ± 6%. In CD8+ T cells, it was 8% to 28% in adults. In CD56+ T cells, it was 30% to 77% in adults. (B) The most complete perforin deficiency was seen in patient P1 with primary HLH. The perforin-staining pattern showed no difference from the isotype control in all cell types. (C) The partial perforin deficiency was seen in patient P10 with primary HLH. The perforin positivity in NK cells was moderately decreased and the perforin positivity in CD8+ and CD56+ T cells was extremely decreased. (D) The percentage of NK cells in P3, a patient with EBV-associated HLH, was 3%, and NK function was extremely decreased. The perforin positivity was markedly increased in CD8+ and CD56+ T cells.

Eleven unrelated HLH patients (7 patients with primary HLH and 4 patients with presumed EBV-associated HLH) and 19 family members were prospectively analyzed with this technique. All but one EBV-associated HLH patient demonstrated absent NK function against K562 targets.

Table 1 shows that 4 of the 7 patients with presumed primary HLH showed lack of intracellular perforin in all cytotoxic cell types (3 with complete and 1 with a partial defeciency). All 4 patients with partial or complete perforin deficiency showed missense or nonsense mutations. A typical example of complete perforin deficiency is shown in Figure 2B. Patient P10 showed a very low intensity of perforin staining (low mean channel fluorescence) in the NK cells (Figure 2C). Analysis of cytotoxic cells from the other 3 patients with presumed primary HLH had normal percentages of perforin-expressing cytotoxic cells for age.

Patients with EBV-associated HLH (Table2) were generally older at diagnosis and were more likely to have very low numbers of NK cells, and increased proportions of CD8+ T cells expressing perforin (Figure2D).

Table 3 lists other syndromes or diseases associated with hemophagocytic complications. A patient with Chediak-Higashi syndrome in accelerated phase showed values within the normal range for her age. On the other hand, a patient with X-linked lymphoproliferative disorder (XLP) showed a markedly increased proportion of perforin-expressing CD8+ T cells. A patient with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) and macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) showed decreased proportions of perforin-expressing cytotoxic cell types.

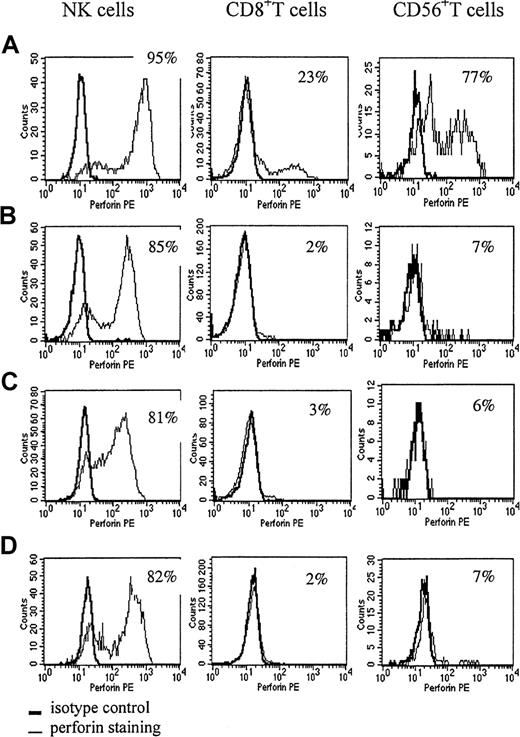

Table 4 lists parents and asymptomatic siblings of patients with primary HLH. The asymptomatic siblings of patients with primary HLH (F (family member) 18, F19, and F20) show extremely decreased NK function. All 3 unrelated siblings had low percentages of perforin-positive T cells; however, in infancy healthy controls also show low percentages of perforin-positive CD8+ T cells. All 3 asymptomatic siblings of HLH patients were proved not to have a perforin mutation. An investigation of 8 parents of patients with perforin deficiencies, who were documented to be carriers of a mutated allele, revealed that all but 1 parent had reduced perforin expression in at least one of the 3 cytotoxic cell types, with either a decreased proportion of perforin-expressing cells and/or decreased mean channel fluorescence compared to healthy adults. Most of the heterozygous carriers showed a slightly decreased percentage of perforin-positive NK cells and very low perforin expression in CD8+ and CD56+ T cells (Figure3B-C). A similar pattern was seen in a patient with JRA and MAS (Figure 3D). The father of patient P10, who is documented to be heterozygous for a mutated perforin gene, showed a reduced proportion of perforin-expressing NK cells. Parents without perforin mutations showed normal percentages of all perforin-positive cell types.

The perforin-staining pattern in 2 parents of patients with HLH and in a patient with hemophagocytic-associated complications.

A healthy adult control (A), a father with a single perforin mutation (B), the mother of patient P11, who had complete perforin deficiency (C), a patient with JRA and MAS (D). (B-C) The perforin positivity of these parents was markedly decreased in CD8+ T cells and CD56+ T cells. Perforin positivity in NK cells of these parents was slightly decreased and mean channel fluorescence was also low. The patient with JRA and MAS showed a similar pattern.

The perforin-staining pattern in 2 parents of patients with HLH and in a patient with hemophagocytic-associated complications.

A healthy adult control (A), a father with a single perforin mutation (B), the mother of patient P11, who had complete perforin deficiency (C), a patient with JRA and MAS (D). (B-C) The perforin positivity of these parents was markedly decreased in CD8+ T cells and CD56+ T cells. Perforin positivity in NK cells of these parents was slightly decreased and mean channel fluorescence was also low. The patient with JRA and MAS showed a similar pattern.

Discussion

HLH frequently occurs in children under 2 years of age as a familial autosomal-recessive disorder.5 To test the utility of intracellular perforin staining by flow cytometry as a means of rapidly identifying children with HLH associated with genetic defects in perforin, we first needed to establish normal ranges in this age group.

Perforin expression is mainly confined to NK cells,6CD8+ T cells,7 CD56+ T cells,8 γδ T cells9 and activated CD4 cells.10,11 In our study, we measured NK cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD56+ T cells. CD56+ T cells are unique extrathymically differentiated lymphocytes. They express both an NK receptor and TCR. CD56+ T cells mediate non–major histocompatibility complex–restricted cytotoxicity and are mostly located in the bone marrow and liver,12 where pathological changes frequently occur in HLH patients. The γδ T cells are mainly located in intestine, where significant symptoms are uncommon in HLH patients. To exclude contamination of CD8+ T cells and CD56+T cells with γδ T cells, we chose TCRαβ instead of CD3 as the costain. As there is a possibility of contamination of NK cells with γδ T cells, we measured NK cells using negativity for CD3 simultaneously. In retrospect, however, no differences in perforin expression between NK (TCRαβ−/CD56+) and NK (CD3−/CD56+) were detectable (unpublished data, August 2000).

Perforin expression in adult peripheral blood has been studied by several investigators.10,11,13 Rutella et al11showed that perforin positivity in NK cells (CD3−/CD56+ and/or CD16+) was 95%. Berthou et al13 reported perforin positivity in NK cells (CD3−/CD56+) to be 92%. Rukavina et al10 showed that perforin positivity in NK cells (CD56+ cells) was 91.2% in adult males and 77.7% in adult females. Our data agree with those data except for perforin positivity in adult females. This difference could be a result of differences in gating strategies. CD56+ cells include CD56+ T cells and NK cells, and if taken together may show lower proportions of perforin-expressing cells, especially in adult females, since some adult females have increased percentages of CD56+ T cells.

Perforin expression in peripheral blood from healthy children has been reported only by Rukavina et al.10 They found that the perforin positivity in NK cells (CD56+ cells) from children was very similar to that of adult males, and that the perforin positivity in CD8+ cells increased with age. Our data concur with these findings. However, Rukavina et al10reported that the average proportion of perforin-positive CD8+ T cells in children was 40%, which is much higher than our findings (7%). The discrepancy is difficult to explain, but may be due to the difference in numbers of specimens (n = 7 for Rukavina) or our selection method of normal samples. Our data for infants regarding the normal proportion of perforin-expressing CD8 cells (1%) are also lower than the cord blood data that was reported by Rukavina (5%),10 but similar to cord blood data published by Berthou (1%).13

We found that 4 of the 7 patients with primary HLH lacked intracellular perforin in all cytotoxic cell types. All of them showed biallelic mutations of the perforin gene. Two had an identical single homozygous nucleotide deletion that caused a frameshift and introduced a premature stop codon. This mutation has previously been reported in patients with HLH.3 In the 2 remaining patients, 4 missense mutations were identified, none of which have previously been reported.

Patients with EBV-associated HLH were generally older at diagnosis. Three of the 4 patients studied here showed low NK functional activity, even though the majority of the NK cells expressed perforin. Therefore, their low NK activity may be related to their low numbers of NK cells. Nagao et al reported that some healthy people show low NK activity and that low NK activity can be due to a low percentage of NK cells, not to functional abnormality.14 We do not know at this time why these patients had low numbers of NK cells during the acute phase of disease. One patient recovered a normal proportion of NK cells as well as normal NK activity when he cleared the EBV infection and was no longer symptomatic with HLH.

Patients with EBV-associated HLH also showed an increased proportion of perforin-expressing CD8+ T cells. Experimental in vitro studies have demonstrated that perforin expression in CD8+T cells is induced by several cytokines, including interleukin-2 (IL-2)15 and/or IL-12, or when the cells are costimulated using anti-CD3 antibody.16 In patients with EBV infection, EBV-specific CD8+ T cells are strikingly induced, and these EBV-specific CD8+ T cells express perforin.17Our preliminary data suggest that EBV-transformed B cell lines (autologous or allogeneic) are also effective in increasing the proportions of perforin-expressing CD8+ T cells in vitro. However, study of 4 healthy adolescents with primary EBV infection (infectious mononucleosis) showed that the subjects maintained normal percentages of NK cells and normal proportions of total perforin-positive CD8 T cells (unpublished data, March 2001). Thus, the mechanism of induction of perforin expression in CD8+ T cells in patients presenting with HLH requires further study. However, our preliminary results suggest that quantitation of NK cells and intracellular perforin staining of CD8+ T cells can potentially distinguish EBV-related HLH from primary HLH.

Studies of perforin from parents of patients with primary HLH have revealed that in all 4 families where the proband had perforin deficiency, the parents had abnormal perforin-staining patterns. The most common parental pattern was a normal percentage of perforin-positive NK cells (although mean channel fluorescent intensity was usually decreased), but a very decreased proportion of perforin-expressing CD8+ T and CD56+ T cells, similar to the profile observed in healthy infants. The ability of heterozygous carriers of PRF1 mutations to generate cytotoxic T cell responses remains to be defined.

We also had the opportunity to test NK function and perforin expression in cytotoxic cells obtained from infant siblings of patients who had died of HLH in the past. The samples (F18, F19, and F20) were submitted for these studies by their referring physicians in an effort to “screen” for possible HLH prior to onset of symptoms. In all 3 unrelated cases no prior information regarding the possibility of familial perforin defects was available. Our analyses showed that all the infants had normal proportions of perforin-positive cytotoxic cells for age but decreased NK function. Subsequent mutational analysis proved that none of these children carried mutations of the PRF1 gene. Since asymptomatic adult carriers of PRF1-negative HLH often have decreased NK function,18 these children may be carriers for the other gene(s) etiologic for HLH. Alternatively, they could be affected. Additional 8-month follow-up indicates that none have yet developed HLH.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that a flow cytometric assay examining 3 different cytotoxic cell populations constitutes a rapid and sensitive approach for detection of HLH patients and carriers of HLH secondary to perforin deficiency. As more cases of HLH are studied to define those with and without perforin mutations, it should be possible to analyze whether any features of the clinical phenotype are associated with perforin deficiency.

This technique appears to provide diagnostic information that, in conjunction with evidence of reduced NK function, may speed the identification of life-threatening HLH in some families and direct further genetic studies of the syndrome. We recommend that all patients with clinical criteria consistent with HLH be studied for NK number and function, as well as having perforin staining of T and NK cytotoxic cells carried out. This screening battery will help confirm the diagnosis of HLH for all patients (decreased or absent NK function) and is highly likely to identify the one third of patients with HLH due to perforin deficiency. In families where perforin deficiency has been documented and the perforin-staining pattern in an affected individual has been determined, this technique can be reliably applied to screen asymptomatic newborn siblings for HLH, in the event that parental mutational analysis of PRF1 has not already been done.

The authors are very grateful to all the participating families and physicians for their generous cooperation in this study and to David Lee, Sue Vergamini, Carol Moore, Terri Ellerhorst, and Darryl Hake for excellent technical support.

Supported by the Ryan Marrocco Memorial Fund, the Zachary Carter Fund for HLH Research, and a grant from the Histiocytosis Association of America.

Submitted May 3, 2001; accepted August 21, 2001.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Alexandra H. Filipovich, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Children's Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039; e-mail: filil0@chmcc.org.