Mouse models of human diseases have contributed immensely to our understanding of the function of genes and their mutations and to the disease phenotype. In some cases, the compatibility of human and mouse signal transduction interactions allows replacement of the mouse genes with their human counterparts. In those cases, disease-causing mutations from patients can be introduced into the mouse germ line allowing direct testing of the gene defect in vivo. Different genetic approaches have been used to create animal models of human diseases caused by gain-of-function mutations. Human transgenes have been bred onto its mouse homologue knock-out background,1 or the human gene has been used to directly replace its murine homologue (ie, knocked-in into the mouse gene locus).2 A necessary assumption of a functional mutant human gene in the mouse environment is the full compatibility of these genes in both species.

Using the transgenic approach, Yu et al3 have recently shown that the human erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) can rescue erythropoiesis and all other developmental defects associated with the mouse EpoR deficiency. The 80-kb human EpoR transgene recapitulated EpoR expression not only in hematopoietic tissues but also in other tissues known to express EpoR. The human EpoR–rescued mice exhibited normal hematologic parameters (including hematocrit) and normal numbers of erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow. However, Yu et al3 also concluded that mouse erythropoietin (Epo) and human EpoR are fully compatible in vivo and questioned earlier observations of others that murine Epo has reduced activity on human cells.4

We think that this conclusion is not warranted and provide the following evidence. We replaced the mouse EpoR gene with its human wild-type and mutant homologue in murine embryonic stem (ES) cells.2 Animals homozygous for the human wild-type human EpoR gene were slightly, but significantly, anemic compared to their littermates (average hematocrit, 45% vs 49%). Additionally, the animals homozygous for the human wild-type EpoR had lower levels of early erythroid progenitors in the bone marrow (in average 12 vs 19 erythroid colonies per 105 cells plated as assessed in semisolid media containing Epo) and smaller spleens before and after phenylhydrazine injection. These data are either compatible with a lower efficiency of in vivo interaction of mouse Epo with human EpoR as suggested by Nicolini et al4 or may be explained by a possible lower efficiency of interaction of the human EpoR with the mouse downstream signaling molecules. Nevertheless, these data prove that mouse and human Epo/EpoR signaling are functionally compatible but have quantitative differences in signaling molecule interactions.

The mutant human EpoR that we knocked-in into the mouse EpoR locus was cloned from a patient with primary familial and congenital polycythemia (PFCP).5 We have shown that mice heterozygous or homozygous for the truncated gain-of-function human EpoR were polycythemic and their erythroid progenitors had increased in vitro sensitivity to both mouse and human Epo.2 Interestingly, another animal model of truncated EpoR without apparent polycythemic phenotype in adults and with comparable in vitro responses of wild-type and mutant erythroid progenitors to Epo was later published by Zang et al.6 The reason for this discrepancy is not clear; in both cases the resulting truncated EpoR contained one tyrosine. However, it is possible that the mutant EpoR isolated from the subject with PFCP has different functional properties than the artificially truncated mouse EpoR used by Zang et al.6 The levels of expression of the mutant EpoR were comparable to the wild-type mouse EpoR in both studies; however, in our model the level of expression was achieved only after removal of the neomycin(neo)–selectable marker by crossing the mice to cre-transgenic mice (Figure1). The animals reported by Zang et al6 had the neo gene retained in the EpoR locus, albeit driven by a different promoter than that used by us.

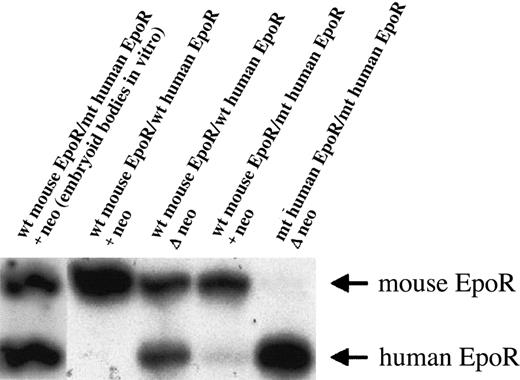

Expression of the human EpoR in the mouse EpoR locus.

Primer extension of reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) product was used to evaluate relative levels of mouse and human EpoR mRNAs, as described.2 The genotypes of ES cells (first lane) or mice (all other lanes) are indicated. The ES cells in the first lane were in vitro–differentiated into embryoid bodies in semisolid media with Epo.7 The cultures were harvested at day 9 of differentiation, and the cells were used as a template for RT-PCR. The presence of a neo-selectable marker did not suppress human EpoR gene expression in the mouse EpoR locus in vitro. In the other lanes, bone marrow cells were used as a template for RT-PCR. The retention of a neo cassette in the human EpoR gene generated a null or hypomorphic allele in vivo. The presence (+neo) or absence (Δ neo) of this selectable marker gene is displayed. wt indicates wild type; mt, mutant.

Expression of the human EpoR in the mouse EpoR locus.

Primer extension of reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) product was used to evaluate relative levels of mouse and human EpoR mRNAs, as described.2 The genotypes of ES cells (first lane) or mice (all other lanes) are indicated. The ES cells in the first lane were in vitro–differentiated into embryoid bodies in semisolid media with Epo.7 The cultures were harvested at day 9 of differentiation, and the cells were used as a template for RT-PCR. The presence of a neo-selectable marker did not suppress human EpoR gene expression in the mouse EpoR locus in vitro. In the other lanes, bone marrow cells were used as a template for RT-PCR. The retention of a neo cassette in the human EpoR gene generated a null or hypomorphic allele in vivo. The presence (+neo) or absence (Δ neo) of this selectable marker gene is displayed. wt indicates wild type; mt, mutant.

While these data indicate that the differences between mouse and human cellular environment exist, they do not undermine the usefulness of the mouse models of human diseases. Our objective, a comparison of disabled and reactivated gain-of-function Epo/EpoR signaling in different tissues through cre-mediated recombination, should help our understanding of the role of Epo signaling in nonerythroid tissues and elucidate the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in PFCP.

Equivalence of mouse and human erythropoietin/erythropoietin receptor signaling

Divoky et al have produced mice expressing the full-length and truncated human EPOR that exhibit mild anemia and polycythemia respectively.1-1 Based on comparisons with mice expressing endogenous erythropoietin receptor (Epor) or a truncated mouse Epor,1-2 they suggest that mouse and human EPO/EPOR signaling are compatible but are different quantitatively in their interactions. Such differences would have important implications for mouse models of human diseases based on human EPOR expression and signaling.

An explanation for differences in mice expressing human EPORmay not reflect different signaling interactions between human and mouse EPO/EPOR but rather the levels of EPORexpression. We found that a human EPOR transgene (80 kb) with expression comparable to the endogenous mouse Epor at all phases of development (yolk sac, fetal liver, and adult spleen and bone marrow)1-3 quantitatively rescues the mouseEpor null phenotype.1-4 Hemoglobin, hematopoietic progenitors (erythroid burst-forming unit, granulocyte macrophage colony-forming unit, granulocyte-erythrocyte-megakaryocyte-macrophage colony-forming unit), and response to anemic stress (reticulocyte count and hematocrit) are similar to control mice. No differences in spleen size were noted, and all animals exhibit an increase in spleen size upon phenylhydrazine treatment. Although higher levels ofEpo induction were detected in themEpor−/−hEPOR+ mice after phenylhydrazine treatment (2.5 that of control animals), hematologic parameters suggest that expression of this humanEPOR transgene behaves largely analogous to endogenous mouseEpor. This transgene also corrects the increased apoptosis associated with mEpor−/− fetal brain and heart development.1-5

The construction of the human EPOR gene by Divoky et al1-1 differ markedly from our human EPORtransgene. We previously carried out careful analysis of the humanEPOR proximal region and found that while much of the transcription activity is contained in a 15–base pair (bp) 5′ proximal promoter fragment, contributions can be seen from the more distal flanking regions.1-6 This is also observed in reporter gene experiments in transgenic mice for promoter fragments extending to 150-bp 5′ and 1778-bp 5′ (Z. Y. Liu, C. Liu, and C. T. Noguchi, unpublished data, 2002). Additional flanking sequences appear to be required to provide a high level of humanEPOR expression in vivo. For the intact humanEPOR transgene, we made more than 15 transgenic lines with low copy number using 3 different genomic fragments. The construct extending only 2 kb 5′ provides an appropriate but low level of tissue-specific EPOR expression, about an order of magnitude lower than the endogenous mEpor.1-7 A significantly higher level of expression on the order of the endogenous gene is observed with 2 other constructs containing longer 5′ regions. Both of these human EPOR gene fragments are able to rescue the mEpor−/− phenotype, and the 80-kb humanEPOR fragment was chosen for further study.1-3This transgene shows appropriate expression in a variety of tissues quantitatively comparable to endogenous mouse Epor,particularly in hematopoietic tissue.

Both the mouse and human proximal promoters contain requisite GATA-1 and SP1 binding sites and are homologous in this region.1-6,1-8 However, homology of the 5′ flanking region does not extend much beyond −60 bp 5′.1-9 To target the mouse locus, Divoky et al used a human EPOR gene fragment (DraI) extending to −550 bp 5′ fused to the 5′ flanking mouse Epor region at −300 bp (NaeI).1-1 This construct retains a species-specific upstream repetitive element that inhibits transcription of the mouse Epor,1-10 and the 550 bp proximal promoter fragment for human EpoR is considerably less than the 1778 bp fragment that resulted in the low level of transgene expression in vivo.1-7 Based on our studies of human EPOR gene expression, the differences in the 5′ region flanking the human EPOR genes used to produce the 2 mouse models are significant. Variations in human EPOR expression due to differences in background strain or site of gene integration are also possible. Careful quantification of EPOR during development and in adult mice would clarify if a lower level of humanEPOR expression in mice produced by Divoky et al accounts for the associated mild anemia without invoking differences between mouse and human EPO/EPOR signaling.

As another piece of evidence that mouse and human EPO/EPORsignaling are different, Divoky and Prchal point to the production of mice expressing truncated Epor with only a single cytoplasmic tyrosine at 343.1-1,1-2 After initial reports of a negative regulatory domain in the cytoplasmic tail of mouseEpor1-11 and humanEPOR,1-12 other truncated deletions in humanEPOR have been associated with polycythemia including the mutation constructed by Divoky et al.1-1 These mice express human EpoR with a truncated deletion just before tyrosine 410 and exhibit a polycythemia phenotype as predicted from the human condition. Interestingly, in addition to direct alteration ofEPO signaling, increased cell-surface expression via posttranslational mechanism(s) has been suggested for a truncatedEPOR associated primary familial and congenital polycythemia.1-13 Other mice expressing a truncated mouseEpoR were constructed by altering the endogenousEpor sequence 3′ of the HindIII site resulting in a truncated mouse Epor with a single cytoplasmic tyrosine that is about 2 dozen amino acids shorter than the Divoky and Prchal deletion.1-2 These mice exhibit largely constitutive erythropoiesis and are not polycythemic. While it is possible that these differences may be inherent in mouse versus humanEPOR, variation in erythrocytosis may also result from the extent or level of expression of the truncations.

Recapitulation of the human phenotype with the truncated humanEPOR by Divoky et al1-1 confirms the similarity ofEPO/EPOR signaling in mouse and human and the potential for using mouse models to understand EPO/EPOR interactions. The differences noted here among the EPOR mouse models illustrate the advantages and limitations of manipulating the mouse genome to alter phenotypic expression. When comparing model systems, careful analysis of gene construction in vivo, mouse strains, and possible integration sites are necessary to ensure comparable expression and analogous gene products. Note that while the original targeting construct for human EPOR by Divoky and Prchal was active in vitro, it was necessary to remove the neomycin (neo)-selectable marker from human EPOR intron 6 to obtain expression in vivo, although the neo gene remains 3′ flanking the endogenous mouse Epor produced by Zang et al.1-1 1-2 Variation in gene expression can become significant, particularly when the differences are small. While human and mouse EPO/EPOR signaling may not be equivalent, we do not see any evidence that they are significantly different in ourEPO/EPOR animal model.