Abstract

A consensus system for classification of mouse lymphoid neoplasms according to their histopathologic and genetic features has been an elusive target for investigators involved in understanding the pathogenesis of spontaneous cancers or modeling human hematopoietic diseases in mice. An international panel of scientists with expertise in mouse and human hematopathology joined with the hematopathology subcommittee of the Mouse Models for Human Cancers Consortium to develop criteria for definition and classification of these diseases together with a standardized nomenclature. The fundamental elements contributing to the scheme are clinical features, morphology, immunophenotype, and genetic characteristics. The resulting classification has numerous parallels to the World Health Organization classification of human lymphoid tumors while recognizing differences that may be species specific. The classification should facilitate communications about mouse models of human lymphoid diseases.

Introduction

A systematic classification of mouse hematopoietic neoplasms was first put forward by Dunn in 1954.1 In this assemblage, tumor types were related to presumed cells of origin, including undifferentiated cells, lymphocytes, granulocytes, “reticulum cells” Types A and B, plasmacytes, and tissue mast cells. Similar names for tumor types can be found in the 1966 Rappaport nomenclature for human hematopoietic tumors.2 Following the identification of T- and B-cell lymphocyte subsets in the 1970s, Pattengale and Taylor3revised the mouse classification scheme to generally parallel the 1974 Lukes-Collins proposal for human hematopoietic neoplasms.4 Within these frameworks, most tumors previously defined as of reticulum cell origin were recognized to correspond to B-cell lineage lymphomas. In 1994, Fredrickson et al5 used the human Kiel classification of 19816as modified in 19887 as the basis for a nomenclature. Among other features, it encompassed previously unrecognized subtypes of mouse B-cell lineage lymphoma, including splenic marginal zone lymphoma (SMZL).8 Most recently, the consensus nomenclatures for human hematopoietic tumors established by the 1995 Revised European-American Lymphoma9 and descendant 2001 World Health Organization (WHO) schemes10,11 were adopted as a model by investigators from the National Institutes of Health in an effort to develop a contemporaneous scheme for classification of mouse lymphoma and leukemia.12-14

The iterative nature of the lists and definitions of disease entities in the mouse derives from the increasingly well-supported presumption that carefully defined and validated model systems can provide fundamental insights into human disorders with attendant implications for prevention and intervention. The opportunities to extend this concept provided by manipulation of the mouse genome were recognized in the formation of the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium (MMHCC) by the United States National Cancer Institute (http://emice.nci.nih.gov). The Hematopathology Subcommittee of the MMHCC was given the charge of developing a consensus list of hematopoietic neoplasms with descriptions and criteria for diagnosis. The goal was to define disease entities that could be recognized by pathologists and related to human disorders where possible. To meet this challenge, gatherings of international experts in human and mouse hematopathology were convened. The result of their deliberations is a proposed classification of hematopoietic diseases that stratifies disorders according to cell lineage. The resulting major subgroups are, accordingly, lymphoid and nonlymphoid. The lymphoid disorders will be discussed here and the nonlymphoid in a separate article.48

General considerations for classification of lymphoid neoplasms of mice

Most of our present knowledge of mouse hematopoietic neoplasms is based on studies of such diseases in inbred and outbred mice occurring either spontaneously or following induction with irradiation, chemicals, or exogenous infection with murine leukemia viruses (MuLVs).3,5,8,15,16 There is considerable strain dependence of disease types and incidence, with much of the differences being genetically determined. Some of these variations are associated with expression of endogenous MuLV and virus-controlling genes,17,18 although infectious MuLVs are not required for induction or progression of many disorders. These considerations are not obviated for diseases developing in genetically engineered mice (GEM)19 but are likely of less importance. Although the range of lymphoid neoplasms seen in conventional mice is broad, it has been substantially extended through genetic engineering. Some of the newly recognized disorders in GEM recapitulate those of humans with greater or lesser levels of fidelity, whereas others appear not to. Indeed, some of the lymphomas and leukemias seen in GEM have never been seen previously as spontaneous lymphomas in mice. In this regard, it is important to remember that only a limited number of strains have been evaluated in a rigorous manner for the characteristics of spontaneous lymphomas. The information at hand that forms much of the basis for our proposals may thus not be representative of the full range of diseases that develop among unmanipulated mice.

A prominent goal of studying mouse tumors is to develop an understanding of pathogenesis that would provide opportunities for preventing or treating similar disorders of humans. It has, therefore, been important to determine whether diseases in the 2 species are true homologs and deserve identical names. We have found this case is often difficult to make. The reasons are multiple. Prominent among these reasons are fundamental differences between the species in the characteristics of primary and secondary lymphoid organs. Uniquely in mice, extramedullary hematopoiesis continues in the red pulp of the spleen throughout life, and the thymus persists well into adulthood. The splenic marginal zone of mice has also been shown to differ significantly from that in humans.20

An additional critical difference is that many modalities used to classify human lymphomas have been applied much less routinely or rigorously to studies of mouse tumors. Without these direct comparisons at hand, guesswork and wishful thinking provide insufficient grounds for identifying true parallels. Consequently, although the committee developed a set of recommendations to be used by pathologists and investigators diagnosing these diseases, these proposals will be altered and updated as additional information becomes available. The fundamental elements contributing to classification of lymphomas in the WHO classification are clinical features, morphology, immunophenotype, and genetic abnormalities. The committee concluded that the same types of information should be developed, when possible, in studies of mouse hematopoietic neoplasms.

Committee recommendations for approaches to diagnosing lymphoid neoplasms of mice are not presented here because of space constraints but are provided in supplementary material available on theBlood website; see the Supplemental Data link at the top of the online article. These recommendations should be reviewed in detail by those new to the field of mouse hematopathology studying either spontaneous or induced models of disease. The guidelines may also provide a helpful review for more established investigators. We anticipate that more uniform application of these approaches to diagnosis and classification by the hematopathology community will facilitate the characterization of lymphomas and leukemias and yield descriptions that can be more readily understood by all. The supplementary material provides approaches to necropsies, sample collection and storage, fixation and staining, as well as flow cytometric and molecular evaluations of tumor samples. Critical parameters for distinguishing reactive from malignant processes complete the online package. The terminology used in the textual material of the print version is based on the definitions provided in the supplementary information.

Comparative human and mouse classifications

The consensus recommendations of the Hematopathology Subcommittee of the MMHCC for classification of mouse lymphoid neoplasms follow the WHO classification in many respects but use distinct terminology when appropriate. Differences in the schemes have several origins that will be dealt with in describing each of the diseases.

Just as the classification of human lymphomas is a work in progress with the WHO scheme being just the most recent version, we view the proposed classification for mouse lymphoid neoplasms as a statement of where we are at present. The scheme presented in Figure1 will be revised as new data on established diseases, both human and mouse, become available and as new disorders are described.

Characteristics of lymphoma/leukemia types

Table 1 compares the features of the lymphoma/leukemia types and their relation to diseases in humans. Several conventions will be followed in the table. First, the phenotype of mature B-cell lymphomas will be given as sIg+ B220 [CD45R(B220)]+ CD19+ with the recognition that other markers may be useful in distinguishing distinct types. Second, the molecular characteristics of mature B-cell lymphomas, regardless of type, will be presented in Table 1 as if both heavy chain and both kappa light chain alleles have undergone rearrangements [IgH R/R, IgK R/R] with the recognition that only one allele of each may be rearranged and that lambda light chain may be rearranged and used in a subset of the neoplasms. In these diagnostic categories, the T-cell locus will be listed as unrearranged, indicating only the T-cell receptor locus (TCRβ G/G), with the recognition that the locus is rearranged in some B-lineage tumors. An expanded description of the occurrence of lymphomas of each diagnostic category is given in Table 5 of the supplementary material, and a more complete listing will be given at the MMHCC Web site (http://mmr.afs.apelon.com/heme/). Finally, although cytologic details are described, they pertain to the appearance of cells in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained tissue sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Representative cases of lymphoma types are shown in Figures 2-4.

Characteristics of lymphoma/leukemia types

| Cell type . | Features . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|---|

| B-cell neoplasms | ||

| Precursor B cell | ||

| Precursor B cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/ leukemia (Pre-B LBL) | Other nomenclature | Lymphoblastic lymphoma; lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous neoplasm of inbred mice. Frequent in some GEM and mice infected with acutely transforming MuLV | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, usually with extensive spread to liver, kidney, and lungs, sometimes to meninges with skull exostoses and hind limb paralysis; leukemic form in about one third of cases | |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Round or ovoid; chromatin fine | |

| Nucleoli | Variable, often single, central and prominent but sometimes small and multiple | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, sometimes starry sky because of apoptosis | |

| Phenotype | Immature B cell, sIg−B220+ CD19+ CD43± Ly6d (ThB)+, Tdt+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal precursor B cell, IgH G/R, IgK G/G | |

| Characteristic | High grade | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Bone marrow precursor B-cell lymphoblast | |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologically and cytologically indistinguishable from most pre-T LBL, BL, and BLL, but CD3− sIg− cytTdT+ | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma and leukemia. The use of the same name in the 2 species seems appropriate because of highly similar histologic, cytologic, phenotypic, and molecular features. | |

| Mature B cell | ||

| Small B-cell lymphoma | Other nomenclature | Small lymphocytic lymphoma; well-differentiated lymphocytic lymphoma |

| (SBL; Figure 2A) | Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous neoplasm of mice; not yet reported for GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly and, in more advanced cases, lymphadenopathy, sometimes with hepatomegaly; one third with blood phase but bone marrow involvement uncommon | |

| Cell size | Small, uniform size and round shape | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant, basophilic | |

| Nuclei | Round; clumped chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Inconspicuous | |

| Mitoses | Few | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIg+ B220+CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Low grade, but can be widespread and aggressive if in leukemic phase | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Small recirculating naive or memory B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Small T-cell lymphoma but sIg+ CD3− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | There are cytologic similarities to human chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL) but clear differences in organ involvement, histologic features, and immunophenotype. Human SLL of the B CLL type has 100% bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement. Histologically, human SLL exhibits occasional pseudo-follicles in some cases, a feature not seen in mice. Human SLL is IgD+, whereas mouse small B-cell lymphoma is not. Human CLL/SLL is considered a single disease in an individual patient, although clinically meaningful distinctions among patients can be made on the basis of genetic lesions and mutated IgV region sequences. In mice, SBL is a disease of secondary lymphoid tissues that may have a blood phase. These many differences led to the choice of a different name for the mouse small B-cell lymphoma. | |

| Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | Other nomenclature | None |

| (SMZL; Figure 2B-D) | Occurrence | Common in a few inbred congenic and recombinant inbred strains as well as some GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Large spleen, occasional splenic node involvement but other nodes and tissues usually negative | |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant, grayish to pale eosinophilic | |

| Nuclei | Round to ovoid; chromatin stippled to vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Not prominent | |

| Mitoses | Few | |

| Pattern | Initially restricted to the marginal zone; later invasive into white and red pulp | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Uniform, grayish to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, low grade initially with progression to high grade with centroblastic morphology and increases in mitotic figures | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Splenic marginal zone B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | None | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Mouse SMZL and human MZL of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type seen to clearly originate from cells of the marginal zone.8,38 39 In contrast, human SMZL may most often result from colonization of the marginal zone by follicular or mantle cell lymphoma rather than being a lymphoma derived from marginal zone B cells.38 Human splenic lymphomas with similarities to mouse SMZL have been observed (N.L.H., unpublished observations, August, 2000) but differed from those defined in the WHO classification as splenic MZL. SMZL is the only well-defined form of MZL in mice. Helicobacter-associated MALT accumulations have been reported but are not yet shown to be clonal.40 | |

| Follicular B-cell lymphoma (FBL; Figure 2E, F) | Other nomenclature | Centroblastic/centrocytic lymphoma; follicular lymphoma; follicular center cell lymphoma, small cell or mixed; reticulum cell sarcoma, type B; lymphoma-pleiomorphic |

| Occurrence | Most common spontaneous lymphoma in many commonly used inbred strains; occurs in some GEM | |

| Necropsy findings | Increasingly enlarged spleen with prominent white pulp that can be seen as white mottling or nodules representing individual enlarged follicles; sometimes nodular enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes; sometimes enlarged Peyer patches | |

| Cell size | Small or large | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant; large cells basophilic or eosinophilic | |

| Nuclei | Cleaved with clumped chromatin or noncleaved, round with vesicular chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Inconspicuous in cleaved cells or usually two prominent and attached to the nuclear membrane in round, noncleaved cells | |

| Mitoses | Variable; none among centrocytes but increasing with frequency of centroblasts | |

| Pattern | Diffuse within splenic white pulp; rare nodular areas in lymph nodes but usually diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+; infiltrating T cells can be numerous | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Low-grade, mixed cell populations resembling those of germinal center, including centrocytes, centroblasts, and immunoblasts; < 50% of cells are centroblasts or immunoblasts | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center B cells, but rarely seen in conjunction with clearly defined germinal centers | |

| Differential diagnosis | Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of centroblastic type at the lower end of centroblast frequency | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | The diagnosis of human follicular lymphoma is based on the recognition in lymph node of follicular structures generated by transformed B cells, follicular dendritic cells, and T cells. The B-cell component consists of a cell mixture with cytologic features of germinal center centrocytes and centroblasts. A diffuse variant of human follicular lymphoma has been described, but it is very rare.41 The cytology of the mouse lymphoma is similar to this variant in that follicular structures are not seen, and white pulp involvement is diffuse. Suggestions of follicular structure are seen rarely in lymph nodes. There is no published immunohistochemical documentation of follicular dendritic cells in the mouse lymphomas, although they occur in normal germinal centers of the mouse. Follicular lymphoma in humans is regularly associated with chromosomal translocations, most commonly t(14;18) involving BCL2, a genetic marker not found in a substantial series of mouse FBL (Pattengale PK, unpublished observations, August, 2000). | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) | ||

| Centroblastic (CB; Figure 3A) | Other nomenclature | Follicular center cell lymphoma, large cell; centroblastic lymphoma |

| Occurrence | Common in inbred strains; some GEM | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly and abdominal lymphadenopathy | |

| Cell size | Medium | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Round, vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, often 2 nucleoli adherent to the nuclear membrane | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Diffuse involvement of the splenic white pulp, progressive effacement of lymph node architecture; 50% or more of cells are centroblasts, less than 10% of cells are immunoblasts. | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center B cell but can also derive from splenic marginal zone B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | FBL and SMZL with high proportions of centroblasts and other types of DLBCL | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | DLBCL, centroblastic variant. In the mouse, this diagnosis has been associated with progression of FBL and SMZL, whereas others have been described simply as diffuse.42 The diagnosis has been made for lymphomas with more than 50% centroblasts in spleen. | |

| Immunoblastic | Other nomenclature | Immunoblastic lymphoma |

| (IB; Figure 3B) | Occurrence | Rare in most inbred strains and GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, extensive infiltration of nonlymphoid tissues | |

| Cell size | Large | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant | |

| Nuclei | Round; chromatin vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, magenta, often bar shaped, attached to nuclear membrane at one side | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse; numerous immunoblasts admixed with a high proportion of centroblasts | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+cytIg+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade; large noncohesive cells, many in apoptosis with a degree of starry sky | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center or postgerminal center B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Anaplastic plasmacytoma, other types of DLBCL | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | DLBCL-immunoblastic morphologic variant; the high proportion of immunoblasts seen in the human disease is rarely seen in mice. | |

| Histiocyte-associated | Other nomenclature | DLCL(HS) |

| (HA; Figure 3C) | Occurrence | Highly variable incidence in inbred strains and common in some GEM |

| | Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly greater than lymphadenopathy, frequent liver involvement with characteristic solid areas |

| Cell size | Large histiocytes (macrophages) admixed with centroblastic and immunoblastic B cells and variable numbers of smaller T cells; foreign body giant cells common | |

| Cytoplasm | Histiocytes abundant, eosinophilic, often vacuolated; scant for B cells | |

| Nuclei | Round, vesicular chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, as for other DLBCL | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Nodular, replacing splenic white and red pulp, often more diffuse in nodes; invasive around larger vessels and diffuse through sinusoids | |

| Phenotype | sIgM+ B220+CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R; some with clonal TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | Sheets of pink, vacuolated histiocytes varying from fusiform to round with substantial numbers of lymphocytes; > 50% of cells are histiocytes | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center or postgerminal center B cells | |

| Differential diagnosis | Other types of DLBCL | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Histiocyte-rich DLBCL would be closest, but the malignant B-cell population in humans is only 5% to 10% of all cells. The frequency of histiocytes is never more than 70% in the mouse. There are 2 histologically indistinguishable subsets of this disease in mice, one with clonal populations of T cells and one without.22In mice, there also appear to be cases of T-cell–rich DLBCL with few if any histiocytes.21 Macrophages are not considered to be neoplastic, but there is no convincing evidence for or against this possibility. | |

| Primary mediastinal (thymic) diffuse | Other nomenclature | None |

| large B-cell lymphoma (PM; Figure 3D) | Occurrence | C57BL/6 mice infected helper-free with the replication-defective MuLV responsible for MAIDS (H.C.M., S. Chattopadhyay, unpublished observations, May 7, 2002.) |

| Necropsy findings | Thymic enlargement, very rarely with enlarged parathymic nodes or with spleen or liver involvement | |

| Cell size | Medium to large | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant to moderate | |

| Nuclei | Round; fine to vesicular chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Partial or complete effacement of normal thymic architecture, beginning in medulla | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, B220+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Diffuse, starry sky | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Thymic B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Polyclonal MAIDS; thymic infiltration by DLBCL of nonthymic origin | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma is a possibility. Sclerosis, which is highly variable in the human disorder, is not seen in the mouse disease. | |

| Classic Burkitt lymphoma (BL; Figure 3E) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Frequent in some MYC transgenic mice | |

| Necropsy findings | Enlarged spleen, all nodes, and often thymus, usually severe | |

| Cell size | Medium/large, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Moderate | |

| Nuclei | Round; chromatin fine | |

| Nucleoli | Multiple, small, prominent | |

| Mitoses | Very numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, sheets of cells with extensive diffuse infiltration of lung, liver, and kidney | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center cells, perhaps founder cells, or postgerminal center B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologically similar to but often half again as large as precursor T cell or precursor B cell and most Burkittlike lymphoma but cytTdT−; MYC translocation or functional equivalent associated with characteristic morphology needed for diagnosis | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Burkitt lymphoma is human counterpart. Because the disease in mice is induced by a myctransgene,25 this disease may represent one of the closest morphologic and molecular parallels between mouse and human diseases. The cell of origin is unknown in either species but may be the small germinal center B-cell blast. | |

| Burkittlike lymphoma (including mature | Other nomenclature | Lymphoblastic lymphoma; DLCL(LL) |

| B-cell lymphomas with lymphoblastic | Occurrence | Frequent in some inbred strains |

| morphology) (BLL; Figure 3F) | Necropsy findings | Generalized lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Nuclei | Round to ovoid; chromatin, fine | |

| Nucleoli | Single, central, prominent or several small | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, sometimes starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, frequent leukemic phase | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center or postgerminal center B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Precursor T-cell and precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma but cytTdT−; also Burkitt lymphomas but no MYC translocation or functional equivalent | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Unknown. May be mouse specific. Structural changes inBcl6 in some cases. See general discussion on diffuse large cell lymphoma. | |

| Plasma cell neoplasm | ||

| Plasmacytoma (PCT; Figure 4A,B) | Other nomenclature | Plasma cell lymphoma |

| Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous tumor in certain inbred mice; readily induced with pristane given intraperitoneally in some inbred mice43 or by infection with acutely transforming retroviruses; appears at high frequency in some GEM | |

| Necropsy findings | Spontaneous disease with splenomegaly and/or lymphadenopathy; pristane-induced tumor appears in peritoneal granulomas; enlarged mesenteric and other nodes and Peyer patches in GEM; bone marrow involvement in v-abltransgenic mice | |

| Cell size | Generally medium-sized plasma cells | |

| Cytoplasm | Moderate, amphophilic, pyroninophilic | |

| Nuclei | Eccentric, round; chromatin, marginated, “clock face” in well-differentiated tumors | |

| Nucleoli | Variable | |

| Mitoses | Variable | |

| Pattern | Pristane-induced tumors with diffuse omental and serosal implants in granulomas exhibiting extensive histiocytosis, also diffuse in mesenteric lymph node, Peyer patches. Spontaneous PCT with splenic white pulp expansion and sometimes diffuse involvement of lymph nodes | |

| Phenotype | Secretory B cell, sIg−, cytIg+, CD138+, CD43±, Ly6D (ThB)+ | |

| Molecular | Immunoglobulin, clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R; T(12;15) in pristane induced43 | |

| Characteristic | Mixture of plasma cells and a few less mature forms. Rare bone marrow involvement | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Mature peripheral (nonbone marrow) plasma cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Severe reactive plasmacytosis | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Uncertain | |

| Extraosseous plasmacytoma (PCT-E) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous tumor in some inbred mice. High frequency in interleukin 6 transgenic mice44 | |

| Necropsy findings | Enlarged spleen and nodes | |

| Cell size | Medium to large plasma cells | |

| Cytoplasm | Small to moderate, amphophilic | |

| Nuclei | Eccentric, round; chromatin marginated in more mature cells to more dispersed in less mature cells | |

| Nucleoli | Variable | |

| Mitoses | Variable | |

| Pattern | Nodular to diffuse involvement of splenic white pulp; lymph nodes show spreading from origins in medullary cords | |

| Phenotype | Secretory B cell, sIg−; cytIg+; CD138+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R; commonly with t(12;15) | |

| Characteristic | Involvement of spleen and nodes rather than peritoneum | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Mature plasma cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Reactive plasmacytosis | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Extraosseous PCT | |

| Anaplastic plasmacytoma (PCT-A; | Other nomenclature | None |

| Figure 4C) | Occurrence | Reported rarely in inbred and GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly | |

| Cell size | Medium to large | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant | |

| Nuclei | Large, round; thick nuclear membrane | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, round, central | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Early secretory B cell, sIgdull; cIg+; CD138dull | |

| Molecular | Clonal mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Mixture of immunoblasts and plasmablasts with intermediate forms; more than 90% of cells are not mature plasma cells | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Mature peripheral (nonbone marrow) plasma cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Immunoblastic lymphoma with differentiation | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | DLCL is plasmablastic morphologic variant. | |

| B–natural killer cell lymphoma (BNKL) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Thymectomized (SL/Kh × AKR/Ms)F1only45 | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly | |

| Cell size | Large | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant, pale blue | |

| Nuclei | Indented | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, 2 to 4 | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | B220+CD5+ IgM+ CD11b+ CD16+NK1.1+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, diffuse with some starry sky appearance | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Unknown | |

| Differential diagnosis | T/NK lymphoma but sIg+CD3− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | None known | |

| T-cell neoplasms | ||

| Precursor T cell neoplasm | ||

| Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic | Other nomenclature | Thymoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma, thymic lymphoma |

| lymphoma/leukemia (Pre-T LBL; | Occurrence | Some inbred strains; many GEM. Most common tumor induced by viruses, chemicals, radiation |

| Figure 4D) | Necropsy findings | Enlarged thymus, variable splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Round; chromatin fine | |

| Nucleoli | Multiple, small/prominent; some with central, prominent nucleoli just as for pre-BLL | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Immature T cell, CD3+, CD4−/CD8− double negative, CD4+/CD8+ double positive, or CD4 or CD8 single positive, TCR+, cytTdT+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal T cell, TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, moderate starry sky, sheets of cells; perivascular infiltration of lung, liver, soft tissue | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Precursor intrathymic T cell but could derive from precursor cells in the bone marrow that home to thymus | |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologically indistinguishable from precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia but CD3+; also very similar to Burkittlike lymphomas but sIg− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma | |

| Mature T cell neoplasm | ||

| Small T-cell lymphoma (STL) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Rare in inbred strains | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, thymus not enlarged | |

| Cell size | Small | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant, basophilic | |

| Nuclei | Small; condensed chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Inconspicuous | |

| Mitoses | Few | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature T cell, CD3+, TCR+, CD4+ or CD8+, cytTdT− | |

| Molecular | Clonal T cell, TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | Low grade, resemble small mature lymphocytes | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Small recirculating T lymphocyte | |

| Differential diagnosis | Small B-cell lymphoma but CD3+ sIg− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | This lymphoma may be unique to the mouse. | |

| T–natural killer cell lymphoma | Other nomenclature | None |

| (TNKL; Figure 4E) | Occurrence | IL-15 transgenic only46 47 |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly | |

| Cell size | Medium to large | |

| Nuclei | Large, chromatin coarse | |

| Nucleoli | Multiple and prominent | |

| Mitoses | Numerous in marrow | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | CD3+, TCRα/β+, CD8±, DX5± | |

| Molecular | TCRβ in about 50% of cases46 or no rearrangements47 | |

| Characteristic | Diffuse infiltration of spleen, nodes, and liver | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Some similarities to T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia. In the mouse, origin is in the marrow, with blood disease evident before secondary involvement of lymphoid and other tissues. | |

| T-cell neoplasm, character undetermined | ||

| Large cell anaplastic lymphoma | Other nomenclature | None |

| (TLCA; Figure 4F) | Occurrence | Rare in inbred strains |

| Necropsy findings | Enlarged thymus, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy | |

| Cell size | Large, pleomorphic | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Large, round to irregular, vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Single, very large, irregular in shape | |

| Mitoses | Very numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, extensive starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Not known | |

| Molecular | Clonal T cell, TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, starry sky, sheets of cells; diffuse infiltration, lung, liver, soft tissue | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Immature or mature cell is not known as analyses of cytTdT have not been performed | |

| Differential diagnosis | None | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | None. Not comparable to human anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T/null. |

| Cell type . | Features . | Characteristics . |

|---|---|---|

| B-cell neoplasms | ||

| Precursor B cell | ||

| Precursor B cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/ leukemia (Pre-B LBL) | Other nomenclature | Lymphoblastic lymphoma; lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous neoplasm of inbred mice. Frequent in some GEM and mice infected with acutely transforming MuLV | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, usually with extensive spread to liver, kidney, and lungs, sometimes to meninges with skull exostoses and hind limb paralysis; leukemic form in about one third of cases | |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Round or ovoid; chromatin fine | |

| Nucleoli | Variable, often single, central and prominent but sometimes small and multiple | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, sometimes starry sky because of apoptosis | |

| Phenotype | Immature B cell, sIg−B220+ CD19+ CD43± Ly6d (ThB)+, Tdt+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal precursor B cell, IgH G/R, IgK G/G | |

| Characteristic | High grade | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Bone marrow precursor B-cell lymphoblast | |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologically and cytologically indistinguishable from most pre-T LBL, BL, and BLL, but CD3− sIg− cytTdT+ | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma and leukemia. The use of the same name in the 2 species seems appropriate because of highly similar histologic, cytologic, phenotypic, and molecular features. | |

| Mature B cell | ||

| Small B-cell lymphoma | Other nomenclature | Small lymphocytic lymphoma; well-differentiated lymphocytic lymphoma |

| (SBL; Figure 2A) | Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous neoplasm of mice; not yet reported for GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly and, in more advanced cases, lymphadenopathy, sometimes with hepatomegaly; one third with blood phase but bone marrow involvement uncommon | |

| Cell size | Small, uniform size and round shape | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant, basophilic | |

| Nuclei | Round; clumped chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Inconspicuous | |

| Mitoses | Few | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIg+ B220+CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Low grade, but can be widespread and aggressive if in leukemic phase | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Small recirculating naive or memory B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Small T-cell lymphoma but sIg+ CD3− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | There are cytologic similarities to human chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic leukemia (SLL) but clear differences in organ involvement, histologic features, and immunophenotype. Human SLL of the B CLL type has 100% bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement. Histologically, human SLL exhibits occasional pseudo-follicles in some cases, a feature not seen in mice. Human SLL is IgD+, whereas mouse small B-cell lymphoma is not. Human CLL/SLL is considered a single disease in an individual patient, although clinically meaningful distinctions among patients can be made on the basis of genetic lesions and mutated IgV region sequences. In mice, SBL is a disease of secondary lymphoid tissues that may have a blood phase. These many differences led to the choice of a different name for the mouse small B-cell lymphoma. | |

| Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | Other nomenclature | None |

| (SMZL; Figure 2B-D) | Occurrence | Common in a few inbred congenic and recombinant inbred strains as well as some GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Large spleen, occasional splenic node involvement but other nodes and tissues usually negative | |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant, grayish to pale eosinophilic | |

| Nuclei | Round to ovoid; chromatin stippled to vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Not prominent | |

| Mitoses | Few | |

| Pattern | Initially restricted to the marginal zone; later invasive into white and red pulp | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Uniform, grayish to pale eosinophilic cytoplasm, low grade initially with progression to high grade with centroblastic morphology and increases in mitotic figures | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Splenic marginal zone B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | None | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Mouse SMZL and human MZL of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type seen to clearly originate from cells of the marginal zone.8,38 39 In contrast, human SMZL may most often result from colonization of the marginal zone by follicular or mantle cell lymphoma rather than being a lymphoma derived from marginal zone B cells.38 Human splenic lymphomas with similarities to mouse SMZL have been observed (N.L.H., unpublished observations, August, 2000) but differed from those defined in the WHO classification as splenic MZL. SMZL is the only well-defined form of MZL in mice. Helicobacter-associated MALT accumulations have been reported but are not yet shown to be clonal.40 | |

| Follicular B-cell lymphoma (FBL; Figure 2E, F) | Other nomenclature | Centroblastic/centrocytic lymphoma; follicular lymphoma; follicular center cell lymphoma, small cell or mixed; reticulum cell sarcoma, type B; lymphoma-pleiomorphic |

| Occurrence | Most common spontaneous lymphoma in many commonly used inbred strains; occurs in some GEM | |

| Necropsy findings | Increasingly enlarged spleen with prominent white pulp that can be seen as white mottling or nodules representing individual enlarged follicles; sometimes nodular enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes; sometimes enlarged Peyer patches | |

| Cell size | Small or large | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant; large cells basophilic or eosinophilic | |

| Nuclei | Cleaved with clumped chromatin or noncleaved, round with vesicular chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Inconspicuous in cleaved cells or usually two prominent and attached to the nuclear membrane in round, noncleaved cells | |

| Mitoses | Variable; none among centrocytes but increasing with frequency of centroblasts | |

| Pattern | Diffuse within splenic white pulp; rare nodular areas in lymph nodes but usually diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+; infiltrating T cells can be numerous | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Low-grade, mixed cell populations resembling those of germinal center, including centrocytes, centroblasts, and immunoblasts; < 50% of cells are centroblasts or immunoblasts | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center B cells, but rarely seen in conjunction with clearly defined germinal centers | |

| Differential diagnosis | Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas of centroblastic type at the lower end of centroblast frequency | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | The diagnosis of human follicular lymphoma is based on the recognition in lymph node of follicular structures generated by transformed B cells, follicular dendritic cells, and T cells. The B-cell component consists of a cell mixture with cytologic features of germinal center centrocytes and centroblasts. A diffuse variant of human follicular lymphoma has been described, but it is very rare.41 The cytology of the mouse lymphoma is similar to this variant in that follicular structures are not seen, and white pulp involvement is diffuse. Suggestions of follicular structure are seen rarely in lymph nodes. There is no published immunohistochemical documentation of follicular dendritic cells in the mouse lymphomas, although they occur in normal germinal centers of the mouse. Follicular lymphoma in humans is regularly associated with chromosomal translocations, most commonly t(14;18) involving BCL2, a genetic marker not found in a substantial series of mouse FBL (Pattengale PK, unpublished observations, August, 2000). | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) | ||

| Centroblastic (CB; Figure 3A) | Other nomenclature | Follicular center cell lymphoma, large cell; centroblastic lymphoma |

| Occurrence | Common in inbred strains; some GEM | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly and abdominal lymphadenopathy | |

| Cell size | Medium | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Round, vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, often 2 nucleoli adherent to the nuclear membrane | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Diffuse involvement of the splenic white pulp, progressive effacement of lymph node architecture; 50% or more of cells are centroblasts, less than 10% of cells are immunoblasts. | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center B cell but can also derive from splenic marginal zone B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | FBL and SMZL with high proportions of centroblasts and other types of DLBCL | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | DLBCL, centroblastic variant. In the mouse, this diagnosis has been associated with progression of FBL and SMZL, whereas others have been described simply as diffuse.42 The diagnosis has been made for lymphomas with more than 50% centroblasts in spleen. | |

| Immunoblastic | Other nomenclature | Immunoblastic lymphoma |

| (IB; Figure 3B) | Occurrence | Rare in most inbred strains and GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, extensive infiltration of nonlymphoid tissues | |

| Cell size | Large | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant | |

| Nuclei | Round; chromatin vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, magenta, often bar shaped, attached to nuclear membrane at one side | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse; numerous immunoblasts admixed with a high proportion of centroblasts | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+cytIg+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade; large noncohesive cells, many in apoptosis with a degree of starry sky | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center or postgerminal center B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Anaplastic plasmacytoma, other types of DLBCL | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | DLBCL-immunoblastic morphologic variant; the high proportion of immunoblasts seen in the human disease is rarely seen in mice. | |

| Histiocyte-associated | Other nomenclature | DLCL(HS) |

| (HA; Figure 3C) | Occurrence | Highly variable incidence in inbred strains and common in some GEM |

| | Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly greater than lymphadenopathy, frequent liver involvement with characteristic solid areas |

| Cell size | Large histiocytes (macrophages) admixed with centroblastic and immunoblastic B cells and variable numbers of smaller T cells; foreign body giant cells common | |

| Cytoplasm | Histiocytes abundant, eosinophilic, often vacuolated; scant for B cells | |

| Nuclei | Round, vesicular chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, as for other DLBCL | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Nodular, replacing splenic white and red pulp, often more diffuse in nodes; invasive around larger vessels and diffuse through sinusoids | |

| Phenotype | sIgM+ B220+CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R; some with clonal TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | Sheets of pink, vacuolated histiocytes varying from fusiform to round with substantial numbers of lymphocytes; > 50% of cells are histiocytes | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center or postgerminal center B cells | |

| Differential diagnosis | Other types of DLBCL | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Histiocyte-rich DLBCL would be closest, but the malignant B-cell population in humans is only 5% to 10% of all cells. The frequency of histiocytes is never more than 70% in the mouse. There are 2 histologically indistinguishable subsets of this disease in mice, one with clonal populations of T cells and one without.22In mice, there also appear to be cases of T-cell–rich DLBCL with few if any histiocytes.21 Macrophages are not considered to be neoplastic, but there is no convincing evidence for or against this possibility. | |

| Primary mediastinal (thymic) diffuse | Other nomenclature | None |

| large B-cell lymphoma (PM; Figure 3D) | Occurrence | C57BL/6 mice infected helper-free with the replication-defective MuLV responsible for MAIDS (H.C.M., S. Chattopadhyay, unpublished observations, May 7, 2002.) |

| Necropsy findings | Thymic enlargement, very rarely with enlarged parathymic nodes or with spleen or liver involvement | |

| Cell size | Medium to large | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant to moderate | |

| Nuclei | Round; fine to vesicular chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Partial or complete effacement of normal thymic architecture, beginning in medulla | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, B220+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Diffuse, starry sky | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Thymic B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Polyclonal MAIDS; thymic infiltration by DLBCL of nonthymic origin | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma is a possibility. Sclerosis, which is highly variable in the human disorder, is not seen in the mouse disease. | |

| Classic Burkitt lymphoma (BL; Figure 3E) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Frequent in some MYC transgenic mice | |

| Necropsy findings | Enlarged spleen, all nodes, and often thymus, usually severe | |

| Cell size | Medium/large, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Moderate | |

| Nuclei | Round; chromatin fine | |

| Nucleoli | Multiple, small, prominent | |

| Mitoses | Very numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+ B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, sheets of cells with extensive diffuse infiltration of lung, liver, and kidney | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center cells, perhaps founder cells, or postgerminal center B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologically similar to but often half again as large as precursor T cell or precursor B cell and most Burkittlike lymphoma but cytTdT−; MYC translocation or functional equivalent associated with characteristic morphology needed for diagnosis | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Burkitt lymphoma is human counterpart. Because the disease in mice is induced by a myctransgene,25 this disease may represent one of the closest morphologic and molecular parallels between mouse and human diseases. The cell of origin is unknown in either species but may be the small germinal center B-cell blast. | |

| Burkittlike lymphoma (including mature | Other nomenclature | Lymphoblastic lymphoma; DLCL(LL) |

| B-cell lymphomas with lymphoblastic | Occurrence | Frequent in some inbred strains |

| morphology) (BLL; Figure 3F) | Necropsy findings | Generalized lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Nuclei | Round to ovoid; chromatin, fine | |

| Nucleoli | Single, central, prominent or several small | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, sometimes starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Mature B cell, sIgM+B220+ CD19+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, frequent leukemic phase | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Germinal center or postgerminal center B cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Precursor T-cell and precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma but cytTdT−; also Burkitt lymphomas but no MYC translocation or functional equivalent | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Unknown. May be mouse specific. Structural changes inBcl6 in some cases. See general discussion on diffuse large cell lymphoma. | |

| Plasma cell neoplasm | ||

| Plasmacytoma (PCT; Figure 4A,B) | Other nomenclature | Plasma cell lymphoma |

| Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous tumor in certain inbred mice; readily induced with pristane given intraperitoneally in some inbred mice43 or by infection with acutely transforming retroviruses; appears at high frequency in some GEM | |

| Necropsy findings | Spontaneous disease with splenomegaly and/or lymphadenopathy; pristane-induced tumor appears in peritoneal granulomas; enlarged mesenteric and other nodes and Peyer patches in GEM; bone marrow involvement in v-abltransgenic mice | |

| Cell size | Generally medium-sized plasma cells | |

| Cytoplasm | Moderate, amphophilic, pyroninophilic | |

| Nuclei | Eccentric, round; chromatin, marginated, “clock face” in well-differentiated tumors | |

| Nucleoli | Variable | |

| Mitoses | Variable | |

| Pattern | Pristane-induced tumors with diffuse omental and serosal implants in granulomas exhibiting extensive histiocytosis, also diffuse in mesenteric lymph node, Peyer patches. Spontaneous PCT with splenic white pulp expansion and sometimes diffuse involvement of lymph nodes | |

| Phenotype | Secretory B cell, sIg−, cytIg+, CD138+, CD43±, Ly6D (ThB)+ | |

| Molecular | Immunoglobulin, clonal, mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R; T(12;15) in pristane induced43 | |

| Characteristic | Mixture of plasma cells and a few less mature forms. Rare bone marrow involvement | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Mature peripheral (nonbone marrow) plasma cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Severe reactive plasmacytosis | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Uncertain | |

| Extraosseous plasmacytoma (PCT-E) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Uncommon spontaneous tumor in some inbred mice. High frequency in interleukin 6 transgenic mice44 | |

| Necropsy findings | Enlarged spleen and nodes | |

| Cell size | Medium to large plasma cells | |

| Cytoplasm | Small to moderate, amphophilic | |

| Nuclei | Eccentric, round; chromatin marginated in more mature cells to more dispersed in less mature cells | |

| Nucleoli | Variable | |

| Mitoses | Variable | |

| Pattern | Nodular to diffuse involvement of splenic white pulp; lymph nodes show spreading from origins in medullary cords | |

| Phenotype | Secretory B cell, sIg−; cytIg+; CD138+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R; commonly with t(12;15) | |

| Characteristic | Involvement of spleen and nodes rather than peritoneum | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Mature plasma cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Reactive plasmacytosis | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Extraosseous PCT | |

| Anaplastic plasmacytoma (PCT-A; | Other nomenclature | None |

| Figure 4C) | Occurrence | Reported rarely in inbred and GEM |

| Necropsy findings | Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly | |

| Cell size | Medium to large | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant | |

| Nuclei | Large, round; thick nuclear membrane | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, round, central | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Early secretory B cell, sIgdull; cIg+; CD138dull | |

| Molecular | Clonal mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | Mixture of immunoblasts and plasmablasts with intermediate forms; more than 90% of cells are not mature plasma cells | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Mature peripheral (nonbone marrow) plasma cell | |

| Differential diagnosis | Immunoblastic lymphoma with differentiation | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | DLCL is plasmablastic morphologic variant. | |

| B–natural killer cell lymphoma (BNKL) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Thymectomized (SL/Kh × AKR/Ms)F1only45 | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly | |

| Cell size | Large | |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant, pale blue | |

| Nuclei | Indented | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent, 2 to 4 | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | B220+CD5+ IgM+ CD11b+ CD16+NK1.1+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal mature B cell, IgH R/R, IgK R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, diffuse with some starry sky appearance | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Unknown | |

| Differential diagnosis | T/NK lymphoma but sIg+CD3− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | None known | |

| T-cell neoplasms | ||

| Precursor T cell neoplasm | ||

| Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic | Other nomenclature | Thymoma, lymphoblastic lymphoma, thymic lymphoma |

| lymphoma/leukemia (Pre-T LBL; | Occurrence | Some inbred strains; many GEM. Most common tumor induced by viruses, chemicals, radiation |

| Figure 4D) | Necropsy findings | Enlarged thymus, variable splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy |

| Cell size | Medium, uniform | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Round; chromatin fine | |

| Nucleoli | Multiple, small/prominent; some with central, prominent nucleoli just as for pre-BLL | |

| Mitoses | Numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Immature T cell, CD3+, CD4−/CD8− double negative, CD4+/CD8+ double positive, or CD4 or CD8 single positive, TCR+, cytTdT+ | |

| Molecular | Clonal T cell, TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, moderate starry sky, sheets of cells; perivascular infiltration of lung, liver, soft tissue | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Precursor intrathymic T cell but could derive from precursor cells in the bone marrow that home to thymus | |

| Differential diagnosis | Histologically indistinguishable from precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia but CD3+; also very similar to Burkittlike lymphomas but sIg− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma | |

| Mature T cell neoplasm | ||

| Small T-cell lymphoma (STL) | Other nomenclature | None |

| Occurrence | Rare in inbred strains | |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, thymus not enlarged | |

| Cell size | Small | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant, basophilic | |

| Nuclei | Small; condensed chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Inconspicuous | |

| Mitoses | Few | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | Mature T cell, CD3+, TCR+, CD4+ or CD8+, cytTdT− | |

| Molecular | Clonal T cell, TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | Low grade, resemble small mature lymphocytes | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Small recirculating T lymphocyte | |

| Differential diagnosis | Small B-cell lymphoma but CD3+ sIg− | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | This lymphoma may be unique to the mouse. | |

| T–natural killer cell lymphoma | Other nomenclature | None |

| (TNKL; Figure 4E) | Occurrence | IL-15 transgenic only46 47 |

| Necropsy findings | Splenomegaly, hepatomegaly | |

| Cell size | Medium to large | |

| Nuclei | Large, chromatin coarse | |

| Nucleoli | Multiple and prominent | |

| Mitoses | Numerous in marrow | |

| Pattern | Diffuse | |

| Phenotype | CD3+, TCRα/β+, CD8±, DX5± | |

| Molecular | TCRβ in about 50% of cases46 or no rearrangements47 | |

| Characteristic | Diffuse infiltration of spleen, nodes, and liver | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | Some similarities to T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia. In the mouse, origin is in the marrow, with blood disease evident before secondary involvement of lymphoid and other tissues. | |

| T-cell neoplasm, character undetermined | ||

| Large cell anaplastic lymphoma | Other nomenclature | None |

| (TLCA; Figure 4F) | Occurrence | Rare in inbred strains |

| Necropsy findings | Enlarged thymus, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy | |

| Cell size | Large, pleomorphic | |

| Cytoplasm | Scant | |

| Nuclei | Large, round to irregular, vesicular | |

| Nucleoli | Single, very large, irregular in shape | |

| Mitoses | Very numerous | |

| Pattern | Diffuse, extensive starry sky | |

| Phenotype | Not known | |

| Molecular | Clonal T cell, TCRβ R/R | |

| Characteristic | High grade, starry sky, sheets of cells; diffuse infiltration, lung, liver, soft tissue | |

| Presumed cell of origin | Immature or mature cell is not known as analyses of cytTdT have not been performed | |

| Differential diagnosis | None | |

| Human counterpart and commentary | None. Not comparable to human anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T/null. |

B-cell lymphomas.

(A) Small B-cell lymphoma. A uniform population of small, mature, round lymphocytes within an expanded white pulp with similar cells invading the red pulp (H&E, × 750). (B) Splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Widening of the marginal zone with medium-sized B cells containing prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm with no red pulp infiltration (H&E, × 400). (C) Advanced SMZL. Evidenced by invasion of the red pulp and compression of the white pulp (H&E, × 400). (D) Advanced SMZL. Centroblastlike cells with mitotic figures obliterating normal architecture. Cytoplasm is moderately extensive (H&E, × 750). (E) Follicular B-cell lymphoma. The pale zone represents loss of small dark lymphocytes in both the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS) and follicle and replacement with mixed centrocytes and centroblasts (H&E, × 150). (F) Follicular B-cell lymphoma. Mixed population of large centroblasts, cleaved centrocytes, and small lymphocytes with few immunoblasts (H&E, × 750).

B-cell lymphomas.

(A) Small B-cell lymphoma. A uniform population of small, mature, round lymphocytes within an expanded white pulp with similar cells invading the red pulp (H&E, × 750). (B) Splenic marginal zone lymphoma. Widening of the marginal zone with medium-sized B cells containing prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm with no red pulp infiltration (H&E, × 400). (C) Advanced SMZL. Evidenced by invasion of the red pulp and compression of the white pulp (H&E, × 400). (D) Advanced SMZL. Centroblastlike cells with mitotic figures obliterating normal architecture. Cytoplasm is moderately extensive (H&E, × 750). (E) Follicular B-cell lymphoma. The pale zone represents loss of small dark lymphocytes in both the periarteriolar lymphoid sheath (PALS) and follicle and replacement with mixed centrocytes and centroblasts (H&E, × 150). (F) Follicular B-cell lymphoma. Mixed population of large centroblasts, cleaved centrocytes, and small lymphocytes with few immunoblasts (H&E, × 750).

B-cell lymphomas.

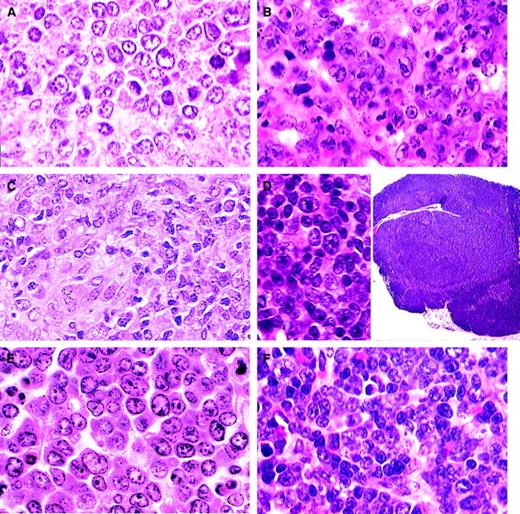

(A) DLBCL-centroblastic. A uniform population of large centroblasts with nuclear membrane-associated nucleoli has completely replaced normal splenic structure (H&E, × 750). (B) DLBCL-immunoblastic. A pleomorphic population of immunoblasts with large nucleoli as well as some centroblasts (H&E, × 750). (C) DLBCL-histiocyte associated. A pleomorphic population of large lymphoid cells with prominent area of histiocytic cells (lower left) (H&E, × 1000). (D) DLBCL-primary mediastinal (thymic). Tumor arising in the thymus composed of a mixed population of B220+ cells (inset; H&E, × 15) including immunoblasts (H&E, × 750). (E) Classic Burkitt lymphoma. Large cells with prominent nucleoli central or in peripheral areas of the nucleus. Apoptosis is a striking feature (H&E, × 1000). (F) Burkittlike lymphoma. Medium-sized cells with central nucleoli or stipple chromatin with moderate apoptosis (H&E, × 750).

B-cell lymphomas.

(A) DLBCL-centroblastic. A uniform population of large centroblasts with nuclear membrane-associated nucleoli has completely replaced normal splenic structure (H&E, × 750). (B) DLBCL-immunoblastic. A pleomorphic population of immunoblasts with large nucleoli as well as some centroblasts (H&E, × 750). (C) DLBCL-histiocyte associated. A pleomorphic population of large lymphoid cells with prominent area of histiocytic cells (lower left) (H&E, × 1000). (D) DLBCL-primary mediastinal (thymic). Tumor arising in the thymus composed of a mixed population of B220+ cells (inset; H&E, × 15) including immunoblasts (H&E, × 750). (E) Classic Burkitt lymphoma. Large cells with prominent nucleoli central or in peripheral areas of the nucleus. Apoptosis is a striking feature (H&E, × 1000). (F) Burkittlike lymphoma. Medium-sized cells with central nucleoli or stipple chromatin with moderate apoptosis (H&E, × 750).

Plasma cell and T-cell lymphomas.

(A) Plasmacytoma. Well-differentiated neoplasm with progression from large plasmablasts with prominent central nucleoli to mature plasma cells (H&E, × 750). (B) Plasmacytoma. Moderately differentiated with maturation of plasmablasts into plasma cells (H&E, × 750). (C) Anaplastic plasmacytoma. Large blast cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm (H&E, × 750). (D) Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Uniform population of medium-sized cells with central or small scattered nucleoli (H&E, × 1000). (E) T-natural killer cell leukemia. Mature small lymphocytes and some large immature lymphoblasts (H&E, × 750). (F) Large cell anaplastic T-cell lymphoma. Comprising mainly large anaplastic immunoblastlike cells with large nucleoli (H&E, × 750).

Plasma cell and T-cell lymphomas.

(A) Plasmacytoma. Well-differentiated neoplasm with progression from large plasmablasts with prominent central nucleoli to mature plasma cells (H&E, × 750). (B) Plasmacytoma. Moderately differentiated with maturation of plasmablasts into plasma cells (H&E, × 750). (C) Anaplastic plasmacytoma. Large blast cells with plentiful amphophilic cytoplasm (H&E, × 750). (D) Precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Uniform population of medium-sized cells with central or small scattered nucleoli (H&E, × 1000). (E) T-natural killer cell leukemia. Mature small lymphocytes and some large immature lymphoblasts (H&E, × 750). (F) Large cell anaplastic T-cell lymphoma. Comprising mainly large anaplastic immunoblastlike cells with large nucleoli (H&E, × 750).

Considerations specific to diffuse large B-cell lymphomas

Hypermutation of immunoglobulin variable region sequences indicates that human lymphomas of this type are of germinal center B-cell origin or have evidence of having passaged the germinal center. Careful studies among medical hematopathologists led to the conclusion that it is difficult to reproducibly distinguish morphologic variants designated centroblastic, immunoblastic, T-cell/histiocyte rich, and other subsets of this disorder defined in pre-WHO nomenclatures.9 The prospect that morphologic variants may in time be associated with specific genetic features defined by using complementary DNA microarray or other technologies led to the suggestion that use of the terminology for the variants remains optional.10 The mouse lymphomas may provide a stronger case for continuing with subset designations in view of highly distinctive morphologic and histologic features of several proposed types (Figure 3A-D). Until such time as these designations can be buttressed by criteria other than histologic appearance, it would seem prudent to keep the use of these morphologic subgroups optional.

There are aspects to distinguishing diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) from other entities in both humans and mice that deserve comment. First, human follicular lymphomas are defined by a combination of what, for purposes of discussion, can be termed cytologic and architectural features within lymph nodes. The cytologic range of these neoplasms comprises primarily centrocytes and centroblasts. The representation of centroblasts is variable, ranging from less than 5 per high-power field to solid sheets of blasts. The architectural hallmark of this disease is poorly defined follicular structures. The proportion of lymph nodes with follicular structures can vary from less than 25% to complete, the remaining areas being diffusely involved. Retention of follicular architecture may thus be said to be the signature distinction between human DLBCL of centroblastic type and follicular lymphomas comprising exclusively centroblasts.

In mice, the cytologic and architectural features that distinguish follicular from DLBCLs are distinct. First, mouse follicular tumors composed almost uniformly of centrocytes are extremely rare, and more evenly balanced populations of centrocytes and centroblasts tend to be the distinguishing feature (Figure 2E). Second, follicular lymphomas in mice usually arise in spleen rather than lymph nodes, meaning that the architectural-distinguishing features of the diseases are fundamentally different for the 2 species. The appearance of involved spleen is nodular at both the gross and microscopic levels with progressive expansion of multiple or all follicles in the white pulp leading to compression of the red pulp as well as the T-cell periarteriolar lymphocytic sheath. Progression may lead to lymphomas with an almost pure population of centroblasts that remain restricted to the white pulp or spread into the red pulp but with the follicular origin still evident. These are centroblastic lymphomas of follicular origin. For historical reasons, it is worth noting that Pattengale and Taylor3 defined follicular center cell lymphomas as small cell, large cell, and mixed. The large cell type corresponds to what we are here calling DLBCL.

Two other subtypes of centroblastic lymphoma have been observed. The first represents a progression of SMZL to a higher grade with clear anatomic evidence of its origins.8 The other type comprises centroblastic tumors for which an origin from the follicle or marginal zone cannot be inferred.

Recent studies have described clonal B-cell lymphomas with high proportions of nonclonal T cells.21 It has been suggested that these mouse tumors may be the equivalent of human T-cell–rich DLBCL, but the frequencies of T cells have not been determined by flow cytometry and may not reach the levels seen in the human disease.

Second, there are mouse lymphomas that are histologically indistinguishable from precursor B-cell and precursor T-cell lymphomas but comprise mature sIg+ B cells.22,23 In the veterinary literature, these lymphomas have been classified together with precursor neoplasms as lymphoblastic lymphoma. The fact that some lymphomas of this type derived from 2 different populations of mice exhibited structural alterations in BCL-6, the most common genetic abnormality of human DLBCL,24 originally was used to argue for their classification as DLBCL, despite their lymphoblastic appearance and the lack of human tumors with this combination of histologic and immunophenotypic features.22,23 With the more recent opportunity to study large numbers of cases of mouse Burkitt lymphoma (Figure 3E),25 it became apparent that a proportion of the sIg+ lymphoblastic tumors resembled mouse Burkitt lymphoma histologically while sharing a proliferative fraction approaching 100%. This finding suggests atypical Burkitt or Burkittlike as perhaps more appropriate terminology for these lymphomas (Figure 3F). In the WHO classification, however, this term is reserved for cases with nonclassical cytology despite proven or likely translocations activating MYC.10 MYC is not rearranged in a significant proportion of the mouse lymphomas of this type, weakening an argument for a change in classification terminology from DLBCL. Nevertheless, the common morphologic and behavioral features of mouse Burkitt lymphoma and mouse sIg+ “lymphoblastic” tumors suggest that they may share analogous pathogenesis. Therefore, we recommend that the term Burkittlike be applied to mature B-cell neoplasms with proliferative fractions approaching 100% even in the absence of MYC translocation. The term Burkitt lymphoma will be reserved for tumors with compatible morphology, phenotype, and MYC dysregulation because of translocation or genetic manipulation. This area is clearly one in which it can be anticipated that molecular profiling will be of great use in sorting out histologically similar mature B-cell lymphomas.

Finally, although the term plasmablastic lymphoma is used for a variant of human DLBCL, it is subsumed under plasma cell neoplasms in mice (Figure 4). The major reason for this decision is that most mouse plasmacytic lymphomas cover a range of cytologic features, ranging from mature monoclonal plasma cells to plasmablasts in varying proportions. The plasmablastic variant represents one extreme. Human plasmablastic lymphoma, by comparison, typically lacks mature plasma cells and can have a morphologic spectrum that ranges from immunoblastic to Burkitt lymphoma.

Borderlands of B-cell lymphoid neoplasia

Several diseases are recognized as occurring in unusual circumstances. One is found in association with 2 different mutations in a common signaling pathway, and a second is found in response to infection with a unique mixture of MuLVs. These are the diseases of mice homozygous for mutations of Fas or Fasl and mice with the retrovirus-induced immunodeficiency syndrome, MAIDS. These diseases are characterized in their early stages by greatly expanded polyclonal proliferations of lymphocytes that are ultimately replaced by monoclonal populations of B cells. Cells in the early stages of these chronic proliferative disorders do not transplant to immunocompetent or immunodeficient hosts, whereas those cells from late-stage animals can be transferred most readily to mice with impaired immunity. The cells that proliferate in the adoptive hosts are clearly lymphomas, but their presence in the original animal is not often apparent, as the expanded populations of nontransformed cells obscure their presence. The committee was hesitant to classify these lymphomas with those readily diagnosed in the primary host because there was no way to determine the stage of the tumor in the primary host or to know how passage in vivo may have influenced histologic appearance and phenotype. The difficulties associated with defining the MAIDS tumors as true lymphoma have been discussed.26 These disorders and their associations with lymphoma are important areas for further study.

Fas- and Fasl-deficient mice

Mice with mutations of Fas or Fasl develop massive lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly due to the polyclonal accumulation of TCRα/β+CD3+CD4−CD8−B220dull“double-negative” T cells.27 Later, up to 60% of mutants from 6 to 15 months of age have clonal populations of B cells (in spleen or lymph nodes) that are not discernible among the mass of double-negative T cells but can be uncovered by transplantation to immunodeficient hosts.28 The tumors are immunoglobulin class switched, but there are no MYC translocations. They also secrete immunoglobulin in the primary animal, on transplantation, and after adaption to tissue culture. The histologic features on transplantation were described as plasmacytoid lymphoma.28 Some humans with mutations in FAS have developed B-cell lymphomas of diverse types, suggesting analogous processes in mice and humans.29 30

Mice with MAIDS

Mice infected with the LP-BM5 mixture of MuLV develop a degree of splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy rivaled only by mice with mutations in Fas and Fasl.31,32Initially, germinal centers are very prominent with large numbers of plasma cells intermixed with centroblasts and increasing numbers of immunoblasts. The disease is initially polyclonal for both B and T cells,33,34 followed by the appearance of oligoclonal populations of B cells more often than of T cells around 8 weeks after infection.33 By 12 weeks, all mice have monoclonal populations of T or B cells that can be transplanted to immunodeficient hosts.35,36 In occasional mice, lymphomas can result in paralysis and death from invasion of the central nervous system.33 Under the proposed nomenclature, the transplants can be described as DLBCL. B-cell lineage lymphomas occur at high frequencies in patients with genetically determined, iatrogenic, or acquired immunodeficiencies such as AIDS,37 providing possible human parallels.

The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the United States government.

Supported in part with funds from the Mouse Models of Human Cancers Consortium, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, and by contract N01-CO56000 from the National Cancer Institute.

H.C.M.III and J.M.W. assisted in the organization of the pathology meeting and prepared the manuscript with assistance from the other authors listed alphabetically. The publication represents the consensus of the committee that included the authors, Robert D. Cardiff, Cory Brayton, James Downing, Hiroshi Hiai, Pier Paolo Pandolfi, Jules J. Berman, Mark S. Tuttle, and Archibald S. Perkins.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Herbert C. Morse III, 7 Center Dr, Rm 7/304, MSC 0760, Bethesda, MD 20892-0760; e-mail: hmorse@niaid.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal