To determine the mechanism of thalidomide's antimyeloma efficacy, we studied the drug's activity in our severe combined immunodeficiency-human (SCID-hu) host system for primary human myeloma. In this model, tumor cells interact with the human microenvironment to produce typical myeloma manifestations in the hosts, including stimulation of neoangiogenesis. Because mice are not able to metabolize thalidomide efficiently, SCID-hu mice received implants of fetal human liver fragments under the renal capsule in addition to subcutaneous implants of the fetal human bone. Myeloma cell growth in these mice was similar to their growth in hosts without liver implant, as assessed by change in levels of circulating human immunoglobulins and by histologic examinations. Thalidomide given daily by peritoneal injection significantly inhibited myeloma growth in 7 of 8 experiments, each with myeloma cells from a different patient, in hosts implanted with human liver. In contrast, thalidomide exerted an antimyeloma effect only in 1 of 10 mice without liver implants. Microvessel density in the untreated controls was higher than in thalidomide-responsive hosts but not different from nonresponsive ones. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by myeloma cells and by other cells in the human bone, determined immunohistochemically, was not affected by thalidomide treatment in any experiment. Our study suggests that thalidomide metabolism is required for its antimyeloma efficacy. Although response to thalidomide was strongly associated with decreased microvessel density, we were unable to conclude whether reduced microvessel density is a primary result of thalidomide's antiangiogenic activity or is secondary to a lessened tumor burden.

Introduction

Myeloma is a B-cell neoplasm characterized by clonal expansion of plasma cells in the hematopoietic bone marrow1 that is associated with neoangiogenesis2 and often with severe bone disease.3

Thalidomide is the first in a new class of drugs with activity even in most advanced cases of myeloma.4-8 Although its reintroduction into clinical use was motivated by its reported antiangiogenic activity,9 10 associating response to thalidomide treatment with antiangiogenic activity has not been possible, even though baseline microvessel density in patients with myeloma has prognostic significance. Thus, the mechanism of thalidomide's antitumor activity in myeloma is unclear.

Recent reports suggest that thalidomide inhibits myeloma cell growth in vitro directly, by inducing G1 growth arrest or by inducing apoptosis associated with activation of related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase,11 and indirectly by interfering with interaction of myeloma cells with their microenvironment.12 This latter observation is in accordance with reports demonstrating that thalidomide alters expression of various adhesion receptors on white blood cells in healthy volunteers and in marmosets.13-15In vivo thalidomide may also exert an antimyeloma effect through stimulation of antimyeloma immune responses by induction of natural killer (NK) cell–mediated myeloma cell lysis16 or by acting as a costimulatory signal to induce cytotoxic responses in T lymphocytes.17 The molecular targets of thalidomide are also not well understood; it has been shown to generate reactive oxygen species that damage DNA and may be responsible for the drug's teratogenic and antiangiogenic activity.18,19 Others have proposed that thalidomide specifically intercalates into DNA promoter regions of genes, such as insulinlike growth factor-1 and fibroblast growth factor-2, and interferes with the production of the growth factors involved in regulating integrin expression.20 The molecular form of thalidomide derivatives responsible for its antimyeloma efficacy, whether hydrolysis products or metabolites, is another unsolved dilemma.10,21 22

We have used the myelomatous severe combined immunodeficiency-human (SCID-hu) model to further investigate the antimyeloma efficacy of thalidomide. In the SCID-hu model, fresh human myeloma cells grow in, interact with, and depend on a human microenvironment, as well as produce typical myeloma manifestations.23-25 In addition to its similarity to clinical myeloma, the SCID-hu system offers the opportunity to determine the importance of metabolism to thalidomide's antimyeloma activity because mice are not able to metabolize thalidomide.26 27 To this end, we compared thalidomide's antimyeloma efficacy in myelomatous SCID-hu hosts that had received implants of pieces of human liver in addition to the human bone. Our results clearly demonstrate that the presence of human liver tissue markedly increases the drug's antimyeloma efficacy.

Materials and methods

Myeloma cells

Heparinized bone marrow aspirates were obtained from 10 patients with active myeloma, 3 patients with plasma cell leukemia, and one blood sample from a fourth patient with plasma cell leukemia, during scheduled clinic visits. A University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Institutional Review Board–approved signed informed consents were obtained and are kept on record. Pertinent patient information is provided in Table 1. The bone marrow samples were separated using Ficoll Hypaque centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The proportion of myeloma cells in the light-density cell fractions (specific gravity ≤ 1.077 g/mL) was determined using CD38/CD45 flow cytometry.28

Patient characteristics and use of tumor cells

| Patient . | Stage* . | Prior therapy . | Patient treated with thalidomide . | Isotype . | Specimen† . | Plasma cells (%)‡ . | Response to thalidomide1-153 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCID-hu B . | SCID-hu B+L . | |||||||

| 1 | IIA | Yes | Yes1-155 | IgG κ | BM | 21 | 102 | ND |

| 2 | IIIA | Yes | Not available | IgG κ | BM | 30 | 12 | ND |

| 3 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | κ light chain | BM1-154 | 38 | 97 | ND |

| 4 | IIIA | Yes | No | IgG λ | BM | 88 | 159 | ND |

| 5 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgG κ + κ | BM# | 56 | 82 | ND |

| 6 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgG κ | BM | 8 | 172 | ND |

| 7 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgA κ + κ | BM | 33 | 85 | 25 |

| 8 | III | Yes | Yes | IgG λ | BM1-154 | 90 | 118 | 115 |

| 9 | IIIB | Yes | Yes | IgA λ + λ | BM | 18 | 91 | 32 |

| 10 | IIIA | No | Yes | IgG λ + λ | BM | 20 | 96 | 42 |

| 11 | IIIA | Yes | No | IgA κ + κ | PB1-154 | 35 | ND | 0.4 |

| 12 | IIIA | No | No | IgG κ | BM | 29 | ND | 0.04 |

| 13 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgM κ | BM | 58 | ND | 56 |

| 14 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgA κ + κ | BM | 60 | ND | 0.001 |

| Patient . | Stage* . | Prior therapy . | Patient treated with thalidomide . | Isotype . | Specimen† . | Plasma cells (%)‡ . | Response to thalidomide1-153 . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCID-hu B . | SCID-hu B+L . | |||||||

| 1 | IIA | Yes | Yes1-155 | IgG κ | BM | 21 | 102 | ND |

| 2 | IIIA | Yes | Not available | IgG κ | BM | 30 | 12 | ND |

| 3 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | κ light chain | BM1-154 | 38 | 97 | ND |

| 4 | IIIA | Yes | No | IgG λ | BM | 88 | 159 | ND |

| 5 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgG κ + κ | BM# | 56 | 82 | ND |

| 6 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgG κ | BM | 8 | 172 | ND |

| 7 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgA κ + κ | BM | 33 | 85 | 25 |

| 8 | III | Yes | Yes | IgG λ | BM1-154 | 90 | 118 | 115 |

| 9 | IIIB | Yes | Yes | IgA λ + λ | BM | 18 | 91 | 32 |

| 10 | IIIA | No | Yes | IgG λ + λ | BM | 20 | 96 | 42 |

| 11 | IIIA | Yes | No | IgA κ + κ | PB1-154 | 35 | ND | 0.4 |

| 12 | IIIA | No | No | IgG κ | BM | 29 | ND | 0.04 |

| 13 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgM κ | BM | 58 | ND | 56 |

| 14 | IIIA | Yes | Yes | IgA κ + κ | BM | 60 | ND | 0.001 |

BM indicates bone marrow; PB, peripheral blood; and ND, experiment not done.

Stage at the time of study, according to the Durie-Salmon staging system.

Specimen used for inoculation into SCID-hu hosts.

Percent of plasma cells in inoculate, determined by CD38/CD45 flow cytometry.

Numbers represent percent change of final hIg in thalidomide-treated host compared to CMC-treated control hosts injected with myeloma cells from the same patient.

Patient has been treated with thalidomide before or after the current study.

Patient had high numbers of circulating plasma cells (plasma cell leukemia).

#Originally diagnosed with primary plasma cell leukemia.

SCID-hu host system

CB.17/Icr-SCID mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) and were housed and monitored in our animal facility. The UAMS Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental procedures and protocols. The human fetal bones and livers were obtained from Advanced Bioscience Resources (ABR; Alameda, CA). Specimens were retrieved from products of conceptions from induced second trimester abortions in compliance with state and federal regulations. Maternal consents were obtained and are kept on record by ABR. For the study, bone and liver tissues were obtained from multiple subjects. For each experiment in which liver was used, the bones and liver were from the same fetus. SCID mice were implanted with a piece of human bone (SCID-hu B hosts) as reported.23 When indicated, several (3-5) 1-mm3 pieces of human liver were implanted under the renal capsule of SCID-hu B mice (SCID-hu B+L hosts) using fine forceps. To approximate the peritoneal layers and to close the skin, 4-0 sutures (Davis and Geck, Wayne, NJ) were used. For each experiment, 2 to 8 × 106 bone marrow cells from one patient, containing 42% ± 25% plasma cells in 50 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were injected directly into the human bone of 2 to 4 SCID-hu hosts. Changes in levels of circulating human immunoglobulin (hIg) of the M-protein isotype were used as an indicator of myeloma growth. When hIg level reached 10 μg/mL or higher in 2 consecutive measurements, 2 mice injected with cells from the same patient were used for study. In 7 of 10 experiments with SCID-hu B hosts and in all experiments with SCID-hu B+L hosts, the host with the higher hIg levels, indicative of higher tumor burden, were selected for treatment, whereas the others served as controls.

Determination of viability and functionality of the implanted human liver

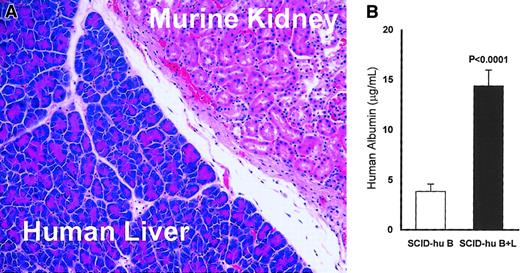

At the end of each experiment, the mice were killed and the liver-implanted kidneys were histologically examined to validate engraftment and viability of the liver tissue (Figure1A). To ascertain functionality of the implanted livers, we measured the level of human albumin in the serum of all experimental animals at the end of each experiment, using a human albumin–specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, TX).

Viability and activity of the implanted human liver in myelomatous SCID-hu hosts (SCID B+L).

(A) Representative section stained with hematoxylin and eosin shows the human liver tissue adjacent to the murine kidney at the end of experiment 11 (25 weeks after liver transplantation; original magnification × 200). Similar data were obtained for all hosts implanted with human liver. (B) Human albumin levels in the serum of SCID-hu B+L (n = 16) are significantly higher than in SCID-hu B (n = 18) mice (P < .0001). Error bars represent SEMs. Thalidomide had no effect on levels of human albumin in thalidomide-treated hosts (see “Results”).

Viability and activity of the implanted human liver in myelomatous SCID-hu hosts (SCID B+L).

(A) Representative section stained with hematoxylin and eosin shows the human liver tissue adjacent to the murine kidney at the end of experiment 11 (25 weeks after liver transplantation; original magnification × 200). Similar data were obtained for all hosts implanted with human liver. (B) Human albumin levels in the serum of SCID-hu B+L (n = 16) are significantly higher than in SCID-hu B (n = 18) mice (P < .0001). Error bars represent SEMs. Thalidomide had no effect on levels of human albumin in thalidomide-treated hosts (see “Results”).

Drug treatment

Thalidomide (kindly provided by Celgene, Warren, NJ) was emulsified in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose in PBS (CMC). Treatment consisted of daily intraperitoneal injections of 200 mg/kg10 29 emulsion, prepared weekly. This dose was well tolerated by the mice. For most experiments, treatment continued for 6 to 8 weeks, whereas in some cases the treatment period was extended as long as 17 weeks to test long-term effects of thalidomide on myeloma growth. Some experiments were terminated when control or nonresponding mice became sick due to high tumor burden. Control animals received CMC alone.

Determination of hIg levels

Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. Blood samples were obtained periodically by retro-orbital bleeding, and sera were prepared and stored at −20°C. The levels of human IgG, IgA, and κ and λ light chains were determined by ELISA as described.23 24 At the end of each experiment, all samples from that experiment were analyzed in the same assay to preclude interassay variability.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

The SCID-hu hosts were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane and killed by cervical dislocation. The tissues were fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for 24 hours. The human bones were further decalcified with 10% (wt/vol) EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), pH 7.0. The tissues and bones were embedded in paraffin for sectioning. Sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated with ethanol, rinsed in PBS, and stained as previously described.23 25 After antigen retrieval, sections were reacted with antibodies to human Ig (Dako, Carpinteria, CA), CD34 (Cell Marque, Austin, TX), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ), developed using an immunoperoxidase staining kit (Dako), and lightly counterstained with Mayer hematoxylin.

Evaluation of microvessel density

Microvessels, visualized by CD34 immunohistochemical staining, were counted in 5 nonoverlapping areas (0.5 mm2/area). Microvessel counts included both areas of tumor infiltration and regenerating bone marrow.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Effects of thalidomide on final hIg were analyzed using the 2-tailed nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. We also analyzed changes in hIg levels (ratio of final-pretreatment hIg levels of thalidomide versus CMC-treated animals) using the Student t test. Levels of human albumin and changes in microvessel density were compared using 2-tailed 2-sample and a paired Student t test, respectively.

Results

Myeloma cell growth in SCID-hu B and SCID-hu B+L mice

Bone marrow cells from 10 patients with myeloma and 3 patients with plasma cell leukemia, and one blood sample from a fourth patient with plasma cell leukemia were studied (Table 1). Light density cells were injected into the human bones of SCID-hu hosts and growth was characterized as previously described.23 24 Myeloma cells from all patients with medullary myeloma grew exclusively within the human bone marrow.

Tumor cells taken from patients with plasma cell leukemia grew also along the outer surface of the human bone, as previously reported.25 Although these cells are independent of the human bone marrow microenvironment, they still require elements of a human microenvironment such as the human vascular endothelial cells and other stromal cells detected in these tumors. As reported, myeloma growth was associated with increased osteoclastogenesis and angiogenesis and frequently with loss in bone density of the human bone. The osteoclasts and microvessels in the human bones were of human origin. The human livers in SCID-hu B+L mice did not contain myeloma cells, as evidenced immunohistochemically by the absence of cIg-expressing cells. The presence of the human liver did not affect tumor growth, dissemination, and manifestations as compared with SCID-hu B hosts inoculated with the same patients cells.

Viability and activity of the implanted human liver

Histologic examination of the human liver-implanted kidneys revealed intact, viable liver tissue adjacent to the murine kidney (Figure 1A). To determine if the human livers were active, the levels of circulating human albumin were measured by ELISA. The mean and median human albumin levels were 3.7- and 4.8-fold, respectively, higher in SCID-hu B+L hosts than in SCID-hu B hosts (P < .0001, Figure 1B). Thalidomide treatment did not affect human albumin levels in SCID-hu B (P < .8) nor in SCID-hu B+L (P < .9) mice.

Effect of thalidomide on myeloma cell growth

The antitumor efficacy of thalidomide was tested in 10 experiments using SCID-hu B mice inoculated with cells from patients 1 to 10 (Table1), and in 8 experiments with SCID-hu B+L mice inoculated with cells from patients 7 to 14 (Table 1). In 4 experiments cells from the same patients (7-10, Table 1) were used in both SCID-hu B and SCID-hu B+L to determine if the implanted liver had an impact on tumor growth, and as a direct comparison of thalidomide's antitumor activity. In all experiments, control mice were treated with CMC only.

Only 1 of the 10 myelomatous SCID-hu B hosts treated with thalidomide had a significant reduction in hIg levels compared to its matching control host (88% reduction, patient 2, Table 1).

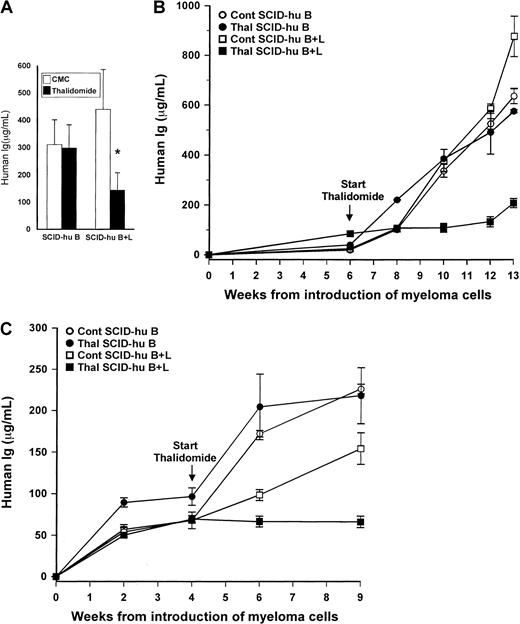

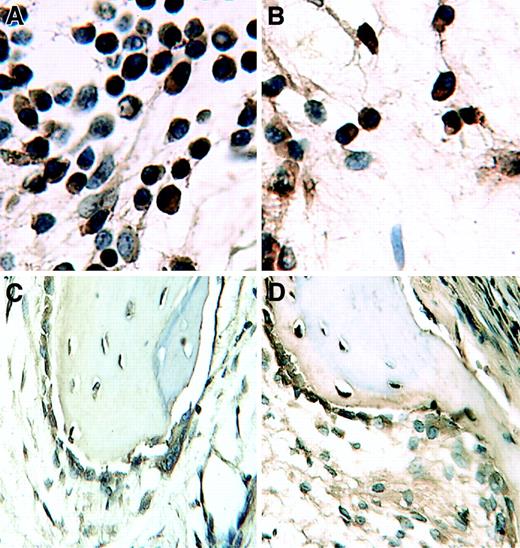

For this group as a whole, the mean hIg levels in thalidomide-treated mice increased from 80 ± 17 μg/mL at initiation of treatment to 298 ± 89 μg/mL, compared to an initial mean level of 97 ± 48 μg/mL and final mean of 311 ± 90 μg/mL for CMC-treated control mice (Figure 2A). The lack of response was evident also histologically, where there were no differences in tumor infiltration between treated and control SCID-hu B hosts (Figure 3A-B). Histologic sections of patient 2, who responded to thalidomide, were similar to those shown for SCID-hu B+L hosts. Thus, for the group as a whole, there was no statistically significant difference in the final-pretreatment ratio of hIg levels (P < .2) or in the final hIg levels of thalidomide-treated compared to CMC-treated control hosts (P < .9).

Contribution of human liver to myelomatous SCID-hu hosts' response to thalidomide.

(A) Final hIg levels (mean + SEM) in thalidomide- and CMC-treated myelomatous SCID-hu B (n = 10) and SCID-hy B+L (n = 8) mice. The asterisk denotes that the change in tumor burden in thalidomide-treated SCID-hu B+L hosts is significantly different from that in CMC-treated controls (P < .0009), whereas the difference in the final hIg levels between these 2 groups is significant at P < .05 (Mann-Whitney U test). The hIg levels in thalidomide- and CMC-treated control SCID-hu B mice were not significantly different. (B-C) Examples of 2 experiments demonstrating the effect of the presence of human liver tissue on myeloma growth and response to thalidomide in SCID-hu hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patients 9 (B) and 10 (C). Values are means ± SEM of replicate readings.

Contribution of human liver to myelomatous SCID-hu hosts' response to thalidomide.

(A) Final hIg levels (mean + SEM) in thalidomide- and CMC-treated myelomatous SCID-hu B (n = 10) and SCID-hy B+L (n = 8) mice. The asterisk denotes that the change in tumor burden in thalidomide-treated SCID-hu B+L hosts is significantly different from that in CMC-treated controls (P < .0009), whereas the difference in the final hIg levels between these 2 groups is significant at P < .05 (Mann-Whitney U test). The hIg levels in thalidomide- and CMC-treated control SCID-hu B mice were not significantly different. (B-C) Examples of 2 experiments demonstrating the effect of the presence of human liver tissue on myeloma growth and response to thalidomide in SCID-hu hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patients 9 (B) and 10 (C). Values are means ± SEM of replicate readings.

In contrast, thalidomide had a profound antimyeloma efficacy in SCID-hu B+L hosts. In 7 of the 8 experiments, thalidomide-treated hosts had at least a 40% lower final hIg level than the matching CMC-treated controls. Only in one of the experiments was the final hIg level of the thalidomide-treated host higher than that in its matching control (patient 8, Table 1). Whereas in the SCID-hu B+L group hIg levels in control animals increased from an initial mean of 41 ± 13 μg/mL to 439 ± 159 μg/mL, in thalidomide-treated hosts the initial and final levels were 97 ± 28 μg/mL and 143 ± 60 μg/mL, respectively (Figure 2A). For this group as a whole, both the differences in the ratios of final-pretreatment hIg levels (P < .0009) or in the final hIg levels (P < .05) between thalidomide-treated and CMC control mice were highly significant. Representative results of the effect of thalidomide on hIg levels in SCID-hu B and SCID-hu B+L hosts from 2 experiments are presented in Figure 2, panels B and C. Histologic evaluation of decalcified human bones from responsive SCID-hu B+L hosts are presented in Figure 3, panels C and D.

Thalidomide reduced myeloma tumor burden only in SCID-hu hosts implanted with human liver.

Sections (stained with hematoxylin and eosin) of decalcified human bones of CMC control (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patient 9. Note marked decrease in myeloma infiltration in the section from a host implanted with human liver (SCID-hu B+L, [D]) and no change in the section from SCID-hu B (B) compared with their respective CMC-treated (SCID-hu B+L, [C] and SCID-hu B, [A]) controls.

Thalidomide reduced myeloma tumor burden only in SCID-hu hosts implanted with human liver.

Sections (stained with hematoxylin and eosin) of decalcified human bones of CMC control (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patient 9. Note marked decrease in myeloma infiltration in the section from a host implanted with human liver (SCID-hu B+L, [D]) and no change in the section from SCID-hu B (B) compared with their respective CMC-treated (SCID-hu B+L, [C] and SCID-hu B, [A]) controls.

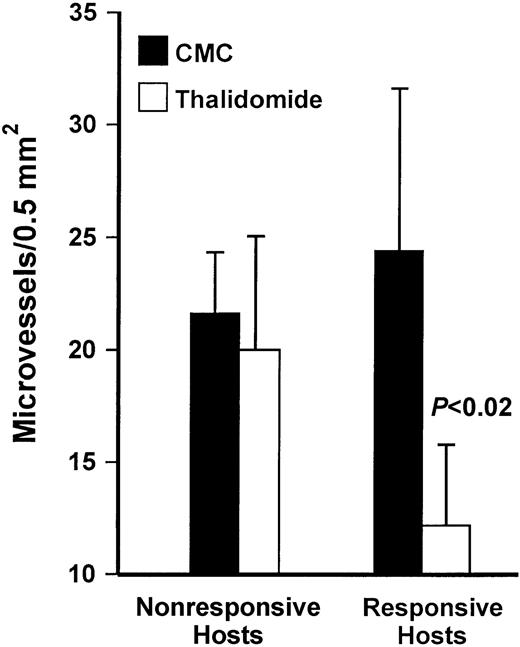

Effect of thalidomide on microvessel density in myeloma bearing SCID-hu hosts

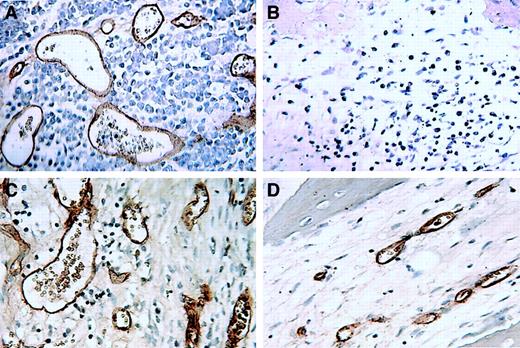

In contrast to nonmyelomatous human bones in SCID-hu mice, growth of primary myeloma cells in the human bone of SCID-hu hosts was associated with increased human microvessel formation that, as reported previously, originated from the implanted human bone.24Microvessel density varied widely between experiments using cells from different patients and within different areas of the human bone in the same experiment. Effects of thalidomide on the number of CD34-reactive microvessels are summarized in Figure 4. There were no differences in the number of microvessels in the human bones of nonresponsive thalidomide-treated hosts and CMC-treated controls. In responsive hosts, inhibition of myeloma growth was associated with reduction in tumor vessels (P < .02). As demonstrated in Figure 5, although microvessel density was reduced in responsive hosts, microvessels were still evident in areas with regenerating marrow and in areas with residual disease in most of the responsive hosts.

Response to thalidomide is associated with reduced microvessel density.

Values are means ± SEM for all responding (n = 7) and nonresponding (n = 7) hosts. In responsive thalidomide-treated hosts, microvessel density was significantly lower than in CMC-treated controls (P < .02). There was no difference in microvessel density between control and thalidomide-treated hosts among the nonresponders.

Response to thalidomide is associated with reduced microvessel density.

Values are means ± SEM for all responding (n = 7) and nonresponding (n = 7) hosts. In responsive thalidomide-treated hosts, microvessel density was significantly lower than in CMC-treated controls (P < .02). There was no difference in microvessel density between control and thalidomide-treated hosts among the nonresponders.

Microvessels in sections of decalcified human bones of thalidomide-responsive myelomatous SCID-hu B+L hosts.

(A-B) Patient 9; (C-D) patient 10. Microvessels in sections from CMC-treated (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) SCID-hu hosts were visualized using immunohistochemical staining for human CD34 expression.

Microvessels in sections of decalcified human bones of thalidomide-responsive myelomatous SCID-hu B+L hosts.

(A-B) Patient 9; (C-D) patient 10. Microvessels in sections from CMC-treated (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) SCID-hu hosts were visualized using immunohistochemical staining for human CD34 expression.

Effect of thalidomide on VEGF expression in myelomatous SCID-hu hosts

We examined whether response to thalidomide and reduced number of microvessels was associated with inhibition of VEGF and bFGF expression. We discerned no effect of thalidomide on cellular expression of VEGF; myeloma cells and other cells in the bone marrow microenvironment (eg, osteoclasts and osteoblasts), in sections of decalcified bones from untreated and responsive hosts, reacted similarly with monoclonal antibody to VEGF (Figure6). Immunohistochemistry for bFGF yielded very faint staining in all cases (not shown).

Response to thalidomide is not associated with reduction of VEGF expression.

Immunohistochemical staining for VEGF in sections of decalcified human bones of SCID-hu hosts showing equal expression in CMC-treated (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patient 13; panels A and B show myeloma cells; panels C and D are bone marrow stromal cells.

Response to thalidomide is not associated with reduction of VEGF expression.

Immunohistochemical staining for VEGF in sections of decalcified human bones of SCID-hu hosts showing equal expression in CMC-treated (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patient 13; panels A and B show myeloma cells; panels C and D are bone marrow stromal cells.

Discussion

We used the SCID-hu model for primary myeloma to study the antimyeloma activity of thalidomide. Specifically, we investigated if the presence of human liver, known to metabolize thalidomide, affects the drug's efficacy, and whether thalidomide's activity is related to its effects on angiogenesis.

The myelomatous SCID-hu model offers the first and only system for studying primary myeloma cells in a human bone marrow microenvironment. It mimics clinical myeloma by supporting myeloma cell growth and producing typical myeloma manifestations.23,24Interference with the supportive microenvironment reduces the ability of myeloma cells to grow and survive.25 In addition to reproducing clinical myeloma, the myelomatous SCID-hu model possesses additional characteristics that make it particularly suitable for studying the activity of thalidomide, that is, lack of a functional immune system, and the inability to metabolize thalidomide.26 27

We studied thalidomide effects in SCID-hu hosts with myeloma cells from 14 patients. Thalidomide exhibited antitumor efficacy in 7 of the 8 hosts implanted with a human liver compared to only 1 of 10 hosts without liver implants. In 3 experiments where thalidomide had antimyeloma efficacy in SCID-hu B+L, the drug did not elicit responses in SCID-hu B hosts. Whereas for technical reasons we did not measure thalidomide metabolites in SCID-hu B+L hosts, we have provided evidence that the human liver implants remained viable and active through the end of the experiments. Therefore, our results clearly demonstrate that the presence of a liver known to metabolize thalidomide has a major impact on the drug's antimyeloma activity, suggesting that thalidomide metabolism is an integral part of its efficacy. These observations concur with reports that in mice, thalidomide is not teratogenic,30 is unable to oxidize DNA,18,31and has no antitumor nor antiangiogenic effects in mice bearing several types of tumors.32-34 Others reported that thalidomide had an antiangiogenic effect in V2 carcinoma growing in rabbits,29 but that human or rabbit microsomes were required for in vitro inhibition of microvessel formation in a rat aorta system and for inhibiting proliferation of human aortic endothelial cells by thalidomide,26 supporting the notion that active metabolites of thalidomide are responsible, at least in part, for its antiangiogenic properties. None of these studies reports measurement of thalidomide metabolism or the presence of its metabolites. This is not to say that only thalidomide metabolites are responsible for its efficacy. In vitro experiments demonstrated that even in the absence of metabolism, high concentrations of thalidomide inhibited angiogenesis and tumor cell growth, and affected cytokine and chemokine expression in various cell types.17,11,12,19,35 36 Additionally, thalidomide hydrolysis products and its metabolites coexist in myeloma patients.

Response to thalidomide in our study was closely associated with reduced microvessel density. With one exception, the microvessel density in the human bones of treated nonresponsive SCID-hu hosts was not different from that in the controls and was lower in responsive hosts than in the controls. Recent published data show that lack of reduction in microvessel density in thalidomide-responsive myeloma patients reflects the balance between tumor regression and endothelial cell apoptosis,37 and if the rate of decline in tumor burden exceeds the rate of endothelial cell apoptosis, microvessels will still be present. We did not detect apoptotic vascular endothelial cells in bones of responsive hosts (data not shown). Therefore, our study did not allow us to distinguish between a primary antiangiogenic effect and a reduction of microvessel density secondary to a reduced tumor burden.

A recent in vitro study suggested that thalidomide might affect myeloma cell growth by inhibiting production of key cytokines such as VEGF in the myeloma microenvironment.12 We could not discern differences in VEGF expression by myeloma cells and other cells in the bone marrow microenvironment of responsive hosts, suggesting that VEGF is not a primary factor in thalidomide's antimyeloma activity.

In addition to its antiangiogenic activity, thalidomide may exert its antimyeloma activity via immunomodulatory functions.16,38Using CD45 flow cytometry, we did not detect circulating human hematopoietic cells in the SCID-hu hosts. Although SCID mice have functional NK cells,39 sections of myelomatous bones from responding SCID-hu hosts showed no histologic evidence of lymphoid infiltration.

In summary, our study shows that response to thalidomide is greatly enhanced in the SCID-hu hosts by the presence of human liver implants known to metabolize thalidomide. Although response to thalidomide was associated with reduced microvessel density, further research is warranted to determine the mechanism of thalidomide's antimyeloma activity.

We thank the faculty and staff of the Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy for their support and dedication to excellence in research and patient care. We also thank the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Office of Grants and Scientific Publications for editorial assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 8, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0939.

Supported by grant CA-55819 from the National Cancer Institute and in part by a grant from the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation and the McCarty Cancer Foundation (S.Y.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Shmuel Yaccoby, Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 W Markham, Slot 776, Little Rock, AR 72205; e-mail:yaccobyshmuel@uams.edu.

![Fig. 3. Thalidomide reduced myeloma tumor burden only in SCID-hu hosts implanted with human liver. / Sections (stained with hematoxylin and eosin) of decalcified human bones of CMC control (A,C) and thalidomide-treated (B,D) hosts inoculated with myeloma cells from patient 9. Note marked decrease in myeloma infiltration in the section from a host implanted with human liver (SCID-hu B+L, [D]) and no change in the section from SCID-hu B (B) compared with their respective CMC-treated (SCID-hu B+L, [C] and SCID-hu B, [A]) controls.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/12/10.1182_blood-2002-03-0939/5/m_h82323503003.jpeg?Expires=1766118241&Signature=UMbRx73TyaZ45WpJrgzGrudarCaXXksGLaVO~RKun2P6p~UqiZXD98h09vxvNR4RlpjaTjBlQH00NGLVmmMhQwJ3y54Hahk7rQ5p~VT2oruQuOaNZGfpjs6L19mszsprmdAfWHS9rIemZyu7ehYPbTvcclpqHKubtiZMQRNiyhlBDR3yvhzD3Yop4JGUSw7IBFTkLPjeRG5cP1HfdtdZsDfcf6Mg8pgagqZ6vl1KwMdACkbTRgJtLTWWuy24PDwPNnr-E8hPZSm9SkSbGTpD9K62y-lCVGgSodX-xNl2xfQIIlVUClepIte0fo3kE7a-WcvY-UlZF9jGWOSh8eG51A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal