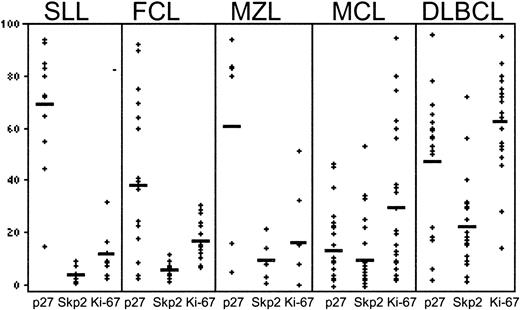

Reduced levels of p27Kip1 are frequent in human cancers and have been associated with poor prognosis. Skp2, a component of the Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex, has been implicated in p27Kip1 degradation. Increased Skp2 levels are seen in some solid tumors and are associated with reduced p27Kip1. We examined the expression of these proteins using single and double immunolabeling in a large series of lymphomas to determine if alterations in their relative levels are associated with changes in cell proliferation and lymphoma subgroups. We studied the expression of Skp2 in low-grade and aggressive B-cell lymphomas (n = 86) and compared them with p27Kip1 and the proliferation index (PI). Fifteen hematopoietic cell lines and peripheral blood lymphocytes were studied by Western blot analysis. In reactive tonsils, Skp2 expression was limited to proliferating germinal center and interfollicular cells. Skp2 expression in small lymphocytic lymphomas (SLLs) and follicular lymphomas (FCLs) was low (mean percentage of positive tumor cells, less than 20%) and was inversely correlated (r = −0.67;P < .0001) with p27Kip1 and positively correlated with the PI (r = 0.82;P < .005). By contrast, whereas most mantle cell lymphomas (MCLs) demonstrated low expression of p27Kip1 and Skp2, a subset (n = 6) expressed high Skp2 (exceeding 20%) with a high PI (exceeding 50%). Skp2 expression was highest in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (DLBCLs) (mean, 22%) and correlated with Ki-67 (r = 0.55;P < .005) but not with p27Kip1. Cytoplasmic Skp2 was seen in a subset of aggressive lymphomas. Our data provide evidence for p27Kip1 degradative function of Skp2 in low-grade lymphomas. The absence of this relationship in aggressive lymphomas suggests that other factors contribute to deregulation of p27Kip1 expression in these tumors.

Introduction

Reduced levels of p27Kip1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, are frequently observed in human cancers1-4 and are associated with aggressive tumor biology5 and poor patient prognosis.6-8 Low levels of the p27Kip1 protein are thought to contribute to malignant cell proliferation owing to its role as a negative regulator of the protein kinases cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (cdk2)/cyclin E and cdk2/cyclin A.9-11 Regulation of p27Kip1 occurs predominantly at the posttranscriptional and posttranslational level,12 through sequestration by either cyclin D1 or cyclin D3 and by phosphorylation and degradation via the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis pathway.11-15 Skp2, a member of the substrate-recognition subunit of Skp1-Cul1-F-box (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex, has been implicated in targeting p27Kip1for degradation.16 In cultured cells, Skp2 protein levels are cell-cycle regulated,17 showing an inverse pattern to that of p27Kip1protein.18 Skp2 overexpression can promote S-phase entry in serum-starved cells by inducing the accumulation of cyclin A, cyclin E,19 and cyclin A–cdk2 activation20 and phosphorylation-dependent degradation of p27Kip1.21 Skp2 has also been implicated in the ubiquitination of other cell-cycle regulatory proteins, including cyclin E and the transcription factor E2F-1.21,22Thus, deregulation of Skp2 may contribute to neoplastic transformation through accelerated p27Kip1 proteolysis. Furthermore, recent studies from our group and others,23,24 using colony-forming assays in soft agar and tumor formation in nude mice,23 have shown that Skp2 has oncogenic potential. Skp2 in cooperation withH-Ras can lead to malignant transformation of primary rodent fibroblasts. Transgenic mice expressing Skp2 targeted to T-lymphoid-lineage–developed T-cell lymphomas in cooperation with activated N-Ras.23 The observation that Skp2 can promote the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p27Kip1 led us to examine the relationship between the expression of Skp2 and p27Kip1 proteins in different categories of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) with different histologic grades and proliferative indices. Our studies demonstrate that Skp2 expression is strongly correlated with the proliferation index in reactive lymphoid tissues. These data provide evidence for the p27Kip1-degradative function of Skp2 in low-grade B-cell lymphomas but suggest the existence of other molecular abnormalities, in addition to Skp2, in the deregulation of p27Kip1expression in aggressive lymphomas.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Tumor specimens from NHLs and reactive lymphoid tissues, including chronic tonsillitis and lymphadenitis, were obtained from the surgical pathology files of the Department of Anatomic Pathology, Sunnybrook Women's College Health Sciences Centre (Toronto, ON, Canada) and the Department of Pathology, University of Utah School of Medicine (Salt Lake City) from 1995 to 1998. Tissues were formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded for histopathologic diagnosis and immunohistochemical study. NHL cases were classified according to the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms.25 This study was approved by the institutional review board of University of Utah.

Isolation and activation of peripheral blood lymphocytes

Peripheral blood was obtained by venipuncture from healthy volunteer donors. Peripheral blood lymphocytes were isolated by density-dependent cell separation on Ficoll as follows. In brief, peripheral blood of healthy donors was diluted in a 1:1 ratio with sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Two volumes of the blood were then laid onto 1 vol Ficoll (60%) and centrifuged at 1400 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature. Mononuclear cells were collected from the buffy coats. Monocytes were removed by plastic adherence on tissue culture–treated Petri dishes for 6 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. The remaining peripheral blood lymphocytes were then maintained under the same conditions as cell lines. Cells were activated by 1% phytohemagglutinin (GibCo BRL, Rockville, MD) and phorbol myristate acetate (5 ng/mL) for 20 hours before being harvested for Western blot analysis.

Cell cultures

Human malignant lymphoma cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) or from the laboratory of Dr N. Berinstein, University of Toronto (ON, Canada). All cell lines (Table1) were maintained in RPMI 1640 (GibCo BRL) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin mixture (GibCo BRL) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Cell lines derived from hematopoietic neoplasms

| Cell line . | Origin . |

|---|---|

| K562 | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| Jurkat | T–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| CEM-6 | T–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| HPB | T–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| Karpas 299 | Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma |

| L428 | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| NCEB | Mantle cell lymphoma |

| Ly-1 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| GM 607 | EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid |

| Karpas 422 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| Raji | Burkitt lymphoma |

| PB 697 | B–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| Nalm-6 | B–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| HH | Mycosis fungoides/Sezary |

| Hut78 | Cutaneous large T-cell lymphoma |

| Cell line . | Origin . |

|---|---|

| K562 | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| Jurkat | T–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| CEM-6 | T–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| HPB | T–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| Karpas 299 | Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma |

| L428 | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| NCEB | Mantle cell lymphoma |

| Ly-1 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| GM 607 | EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid |

| Karpas 422 | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

| Raji | Burkitt lymphoma |

| PB 697 | B–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| Nalm-6 | B–acute lymphoblastic lymphoma |

| HH | Mycosis fungoides/Sezary |

| Hut78 | Cutaneous large T-cell lymphoma |

EBV indicates Epstein-Barr virus.

Preparation of cell lysates and immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane–HCl], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1% triton-× 100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], and 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO). Fifteen micrograms of protein was resolved in a 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel by means of a BioRad (Hercules, CA ) mini-gel system. Separated proteins were then transferred onto a nitrocellulose film by means of a semidry transfer apparatus (BioRad). The following antibodies were used for immunoblot analysis: mouse monoclonal antibody against p27Kip1 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), polyclonal Skp2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), and monoclonal antibody 1 (MIB1; Novocastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom), which recognizes an epitope of the Ki-67 antigen. Protein bands were visualized by means of the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Because of significant differences in the molecular weights of p27Kip1 (27 kDa) and Skp2 (45 kDa), the same blot was reused after stripping, and signals were developed for an equal period of time. Densitometry was performed by means of the Molecular Dynamics Imaging system and ImageQuant 3.3 software (Amersham Biosciences, Sunnyvale, CA) to quantify relative amounts of protein detected on Western blots.

Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions

Cells were subfractionated as previously described,3 with minor modifications. In brief, cells at subconfluency conditions were collected and resuspended in hypertonic buffer supplemented with 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Chemical). After swelling in ice for 20 minutes, plasma membranes were disrupted by repeated pipetting. Cell breakage was assessed by microscopic observation. Samples were microcentrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C to collect cytoplasmic fractions (supernatant). The pellets were washed once with hypertonic buffer and resuspended in RIPA buffer. The nuclear fraction (supernatant) was recovered by microcentrifugation at top speed at 4°C for 10 minutes.

Immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting, 200 μg proteins in 500 μL RIPA buffer was mixed with 2 μg antibodies and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Immune complexes were collected on protein G-Agarose beads (GibCo BRL) and washed 5 times in lysis buffer.

Immunohistochemistry

Serial sections that were 5-μm thick were mounted on glass slides coated with 2% aminopropyltrioxysilane (APES; Sigma Chemical) in acetone. Sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanols. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by immersion in 0.3% methanolic peroxide for 15 minutes. Immunoreactivity of p27Kip1 was enhanced by microwaving by incubating the tissue sections for 10 minutes in 0.1 M citrate buffer. Expression of p27Kip1 protein was detected by incubating the tissue sections with a monoclonal antibody to p27Kip1 (Transduction Laboratories) diluted 1:500. The proliferation index was assessed by using an MIB1 monoclonal antibody (Novocastra) that recognizes a formalin-resistant epitope of the Ki-67 antigen. Skp2 protein expression was detected by incubating a monoclonal antibody to Skp2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:50 for 32 minutes. The sections were then incubated with a biotinylated peroxidase agent (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA). Antigen-antibody reactions were visualized with the chromogen diaminobenzadine. Normal mouse serum containing mixed immunoglobulins at a concentration approximating that of the primary antibody was used as a negative control. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. A normal tonsil was used as a positive control for all antibodies. Double immunohistochemistry was performed with the use of citrate buffer, pH 6.0, for 3 minutes. The primary antibody p27Kip1 was used at a dilution of 1:30 for 32 minutes and was detected with the use of diaminobenzadine. Antibody to Skp2 was used at a dilution of 1:10 for 32 minutes and blocked with levamisole for 16 minutes, after which the antigen-antibody reaction was visualized with the use of alkaline phosphatase red and was counterstained with hematoxylin.

Interpretation of immunohistochemical stains

The percentages of neoplastic cells expressing p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67 by immunohistochemical stains were assessed in each case by counting 400 cells from at least 3 different representative fields with the use of the 50 × or 100 × oil objectives. Distinct nuclear staining that was appreciably above background was considered positive. Expression of p27Kip1 and Skp2 by less than 20% of the total cell population was considered low, and expression exceeding 20% was considered high.23

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to present the distribution of the measured parameters. The Pearson rank correlation coefficient was used to describe correlation between Skp2 and p27Kip1; between Skp2 and Ki-67; and between p27Kip1 and Ki-67 expression. The 2-tailed Student t test was used to evaluate the significance of these correlations. P < .05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

Expression of Skp2 and p27Kip1 in cell lines derived from hematopoietic neoplasms

Western blot analysis of total cell lysates obtained from cell lines of myeloid, B-lymphoid, and T-lymphoid origin (Table1) demonstrated Skp2 protein expression in all cell lines. Negligible levels were detected in the Hodgkin-derived cell line L428 and the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell line Karpas 422. In comparison with p27Kip1 levels, which were abundantly expressed in most cell lines (10 of 15, 67%), the levels of Skp2 protein were low (Figure 1). Although quiescent peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) expressed high levels of p27Kip1 protein that decreased with activation, the levels of Skp2 protein were not detectable in either cell population.

Expression of Skp2 and p27Kip1 in PBLs and cell lines derived from hematopoietic neoplasms.

Quiescent PBLs express high levels of p27Kip1 that decrease upon activation with phytohemagglutinin (PHA). Levels of Skp2 protein expression show an inverse relationship to levels of p27Kip1 in 10 of 15 cell lines. Quiescent PBLs and their activated counterparts show the absence of Skp2 protein expression.

Expression of Skp2 and p27Kip1 in PBLs and cell lines derived from hematopoietic neoplasms.

Quiescent PBLs express high levels of p27Kip1 that decrease upon activation with phytohemagglutinin (PHA). Levels of Skp2 protein expression show an inverse relationship to levels of p27Kip1 in 10 of 15 cell lines. Quiescent PBLs and their activated counterparts show the absence of Skp2 protein expression.

Expression of Skp2 in reactive lymphoid tissue and non-Hodgkin lymphomas

We studied the expression of Skp2, p27Kip1, and Ki-67 in reactive tonsils and lymph nodes and in 86 B-lineage non-Hodgkin lymphomas composed of 12 cases of small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), 19 cases of follicular lymphoma (FCL), 6 cases of nodal marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), 29 cases of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and 20 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The results are presented in Figures2 and3 and summarized in Tables2 and 3. In reactive lymphoid tissues (Figure 2A), Skp2 was characteristically expressed in a subset of the proliferating germinal center (GC) cells and in rare interfollicular cells. This staining pattern was similar to that of Ki-67 but with significantly lower intensity. By contrast, strong p27Kip1 expression was seen in the quiescent cells of the follicular mantle zone and in interfollicular T lymphocytes, whereas only rare cells in the GC were positive.

Immunohistochemical analysis of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67 expression in reactive lymphoid tissues and malignant lymphoma.

(A) Follicular hyperplasia. Reactive lymph nodes (p27Kip1and Skp2). Expression of p27Kip1 is present in quiescent cells of the follicular mantle zones and interfollicular T lymphocytes. Scattered germinal center centroblasts and interfollicular immunoblasts express Skp2. This staining pattern is similar to that of Ki-67 (data not shown). (B) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/SLL (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Skp2 and Ki-67 expression highlights prolymphocytes and proliferation centers. (C) FCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). A section of low-grade FCL shows intense diffuse reactivity for p27Kip1 in neoplastic and reactive lymphoid cells. Only scattered germinal center cells express Skp2 and Ki-67 relative to p27Kip1. (D) MCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Scattered tumor cells show similar levels of Skp2, p27Kip1, and Ki-67 expression. (E) DLBCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Section of intermediate-grade DLBCL shows scattered tumor cells expressing p27Kip1. High levels of Skp2 and Ki-67 expression are seen in DLBCLs. The results show that the expression of Skp2 mirrors that of the proliferation marker Ki-67. (F) Double immunohistochemistry confirms the findings of single-immunolabeling studies. (Reactive lymph nodes shown for SLL/CLL, MZL, DLBCL.) Skp2+cells within proliferating germinal centers of a reactive lymph node are highlighted by the use of pink, whereas the p27Kip1-positive cells within the mantle zones are brown. In a case of SLL/CLL, Skp2+ cells (pink) highlight proliferating immunoblasts within the pseudo-proliferation growth centers. Most of the small neoplastic lymphocytes of SLL/CLL are p27Kip1 positive (brown). In MZL, Skp2+ cells (pink) highlight large centroblasts within a colonized follicle, whereas the surrounding small neoplastic and reactive lymphocytes are p27Kip1 positive (brown). A DLBCL with a high proliferative index shows many Skp2+ cells (pink), with only scattered small reactive lymphocytes and endothelial cells that express p27Kip1 (brown). Original magnification A, ×100; B-F, ×200.

Immunohistochemical analysis of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67 expression in reactive lymphoid tissues and malignant lymphoma.

(A) Follicular hyperplasia. Reactive lymph nodes (p27Kip1and Skp2). Expression of p27Kip1 is present in quiescent cells of the follicular mantle zones and interfollicular T lymphocytes. Scattered germinal center centroblasts and interfollicular immunoblasts express Skp2. This staining pattern is similar to that of Ki-67 (data not shown). (B) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/SLL (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Skp2 and Ki-67 expression highlights prolymphocytes and proliferation centers. (C) FCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). A section of low-grade FCL shows intense diffuse reactivity for p27Kip1 in neoplastic and reactive lymphoid cells. Only scattered germinal center cells express Skp2 and Ki-67 relative to p27Kip1. (D) MCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Scattered tumor cells show similar levels of Skp2, p27Kip1, and Ki-67 expression. (E) DLBCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Section of intermediate-grade DLBCL shows scattered tumor cells expressing p27Kip1. High levels of Skp2 and Ki-67 expression are seen in DLBCLs. The results show that the expression of Skp2 mirrors that of the proliferation marker Ki-67. (F) Double immunohistochemistry confirms the findings of single-immunolabeling studies. (Reactive lymph nodes shown for SLL/CLL, MZL, DLBCL.) Skp2+cells within proliferating germinal centers of a reactive lymph node are highlighted by the use of pink, whereas the p27Kip1-positive cells within the mantle zones are brown. In a case of SLL/CLL, Skp2+ cells (pink) highlight proliferating immunoblasts within the pseudo-proliferation growth centers. Most of the small neoplastic lymphocytes of SLL/CLL are p27Kip1 positive (brown). In MZL, Skp2+ cells (pink) highlight large centroblasts within a colonized follicle, whereas the surrounding small neoplastic and reactive lymphocytes are p27Kip1 positive (brown). A DLBCL with a high proliferative index shows many Skp2+ cells (pink), with only scattered small reactive lymphocytes and endothelial cells that express p27Kip1 (brown). Original magnification A, ×100; B-F, ×200.

Graphic representation of relationship between p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67 expression in malignant lymphoma.

Graphic representation of relationship between p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67 expression in malignant lymphoma.

Mean expression of Skp2, p27Kip1, and Ki-67 expression in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma

| Type of lymphoma . | Positive cells, mean (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p27 . | Skp2 . | Ki-67 . | |

| SLL/CLL | 69 | 4 | 12 |

| FCL | 36 | 6 | 17 |

| MZL | 61 | 10 | 21 |

| MCL | 11 | 9 | 28 |

| DLBCL | 49 | 25 | 63 |

| Type of lymphoma . | Positive cells, mean (%) . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p27 . | Skp2 . | Ki-67 . | |

| SLL/CLL | 69 | 4 | 12 |

| FCL | 36 | 6 | 17 |

| MZL | 61 | 10 | 21 |

| MCL | 11 | 9 | 28 |

| DLBCL | 49 | 25 | 63 |

Data from 86 cases of B-cell NHL are presented. There were 12 cases of SLL/CLL; 19 cases of FCL; 6 cases of MZL; 29 cases of MCL; and 20 cases of DLBCL.

Correlation coefficients for the relationship between Skp2 and p27Kip1 and for the relationship between Skp2 and Ki-67 expression in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma

| . | r . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| SLL/CLL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.75 | < .0000 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.85 | < .0057 |

| FCL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.56 | < .0003 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.65 | < .0000 |

| MZL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.89 | < .0231 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.48 | < .2310 |

| MCL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.29 | < .3838 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.91 | < .0015 |

| DLBCL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | 0.17 | < .0009 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.55 | < .0000 |

| . | r . | P . |

|---|---|---|

| SLL/CLL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.75 | < .0000 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.85 | < .0057 |

| FCL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.56 | < .0003 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.65 | < .0000 |

| MZL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.89 | < .0231 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.48 | < .2310 |

| MCL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | − 0.29 | < .3838 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.91 | < .0015 |

| DLBCL | ||

| Skp2, p27 | 0.17 | < .0009 |

| Skp2, Ki-67 | 0.55 | < .0000 |

See Table 2 footnote for numbers of cases.

In B-CLL/SLL, Skp2 expression was limited to prolymphocytes and paraimmunoblasts within the proliferation centers (Figure 2B). The mean Skp2 expression in 12 CLL/SLLs was 4% (Table 2). The p27Kip1 protein showed a staining pattern inverse to that of Skp2, with numerous neoplastic lymphocytes demonstrating intense expression (mean, 69%). A strong inverse relationship was seen between Skp2 expression and p27Kip1 expression (r = −0.75; P < .00001). There was also a strong positive correlation between Skp2 and the proliferation index as measured by Ki-67 expression (r = 0.85;P < .0057).

In FCL, Skp2 expression was seen in large centroblasts of the neoplastic follicles, whereas the majority of the small-cleaved cells were negative (Figure 2C). The mean Skp2 expression in FCL was 6% (range, 2% to 12%). The p27Kip1 expression was predominantly seen within nonneoplastic mantle zones and paracortical T cells. An inverse correlation was observed between Skp2 and p27Kip1 expression (r = −0.56;P < .0003), whereas a positive correlation was observed between Skp2 and Ki-67 (r = 0.65;P < .0001).

Of 6 patients with MZL, the mean Skp2 expression was 10%, with staining observed in large transformed centroblasts (data not shown). The mean p27Kip1 expression was high (61%), with most immunoreactivity observed within small neoplastic and reactive lymphocytes. Skp2 expression correlated inversely with p27Kip1 (r = −0.89; P < .01), but there was no significant correlation with Ki-67 (r = 0.48; P = .2).

As a group, MCLs had low levels of Skp2 expression (mean, 9%) (Figure2D); a poor negative correlation that was not statistically significant (r = −0.29) was observed between Skp2 and p27Kip1. Two distinct groups of MCLs however, were observed on the basis of Skp2 expression. In 23 of 29 cases (80%), the expression of Skp2 protein was low (mean, 4%), and poor correlation was seen with p27Kip1, although there was a strong positive correlation with proliferation. The remaining 6 cases of MCL (20%) demonstrated high Skp2 expression (mean, 28%), which was inversely correlated with p27Kip1. The mean Ki-67 in the 23 cases of MCL with low Skp2 was 16% (range, 2% to 35%), whereas the mean percentage of cells with Ki-67 expression in the 6 cases with high Skp2 was 64% (range, 51% to 85%). Three of the 6 MCLs with increased Skp2 had morphologic features of blastic mantle cell lymphoma and had proliferation indices of 54%, 72%, and 85%. The remaining 3 cases exhibited histology of typical MCL and demonstrated a PI exceeding 50%. As a group, a strong positive correlation existed between Skp2 and Ki-67 expression (r = 0.91; P < .0015) in MCL.

Skp2 levels exhibited the most variability among DLBCLs, with 11 cases showing low (less than 20%) expression while 9 cases demonstrated high (greater than 20%) expression (Figure 2E). The mean percentage of Skp2 expression (25%) did not correlate with p27Kip1(r = 0.17; P < .001) expression but did correlate with expression of Ki-67 (r = 0.55;P < .0001). Notably, cytoplasmic Skp2 was seen in a subset of the DLBCLs but not in the other lymphoma groups (data not shown).

Double immunolabeling was performed in a selected number of cases (Figure 2F). Skp2 expression, indicated by alkaline phosphatase (pink), and p27Kip1 expression, indicated by diaminobenzadine (brown), confirm the findings seen by single-immunohistochemical studies.

In all cases of NHLs analyzed, the percentage of cells expressing Skp2 never exceeded that of Ki-67. In the low-grade B-cell lymphomas, CLL/SLL, FCL, and MZL, the vast majority (92%) of cases showed lower than 10% Skp2 expression with high p27Kip1 expression, and a clear-cut inverse relationship was observed between the 2 proteins. Overall, the highest percentage of Skp2+ cells were seen in the DLBCL group (mean, 25%) as well as the blastic variants of MCL (mean, 64%).

Skp2 is expressed in the cytoplasm and complexes with p27Kip1

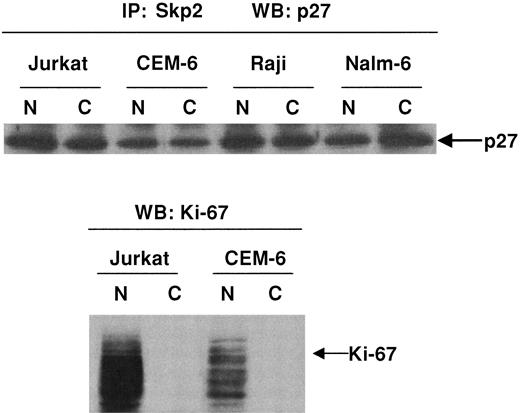

We observed cytoplasmic expression of Skp2 in 2 cases of DLBCLs by immunohistochemistry (data not shown). We sought to determine whether complexes of Skp2 and p27Kip1 were present in subcellular fractions of lymphoma cells. Figure4 demonstrates that immunoprecipitation of Jurkat, CEM-6, Raji, and Nalm-6 cells with anti-Skp2 followed by immunoblotting with p27Kip1 showed a physical relationship between the 2 proteins within both the nuclear and the cytoplasmic fractions. Western blot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions with an antibody against Ki-67, however, showed that its expression was restricted to the nuclear fractions.

Demonstration of p27Kip1/Skp2 complexes in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions.

Immunoprecipitation studies demonstrate p27Kip1/Skp2 complexes within nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Subcellular fractions of Jurkat, CEM-6, Raji, and Nalm-6 cells were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal antibody to Skp2 followed by Western blot analysis with anti-p27Kip1. Subcellular fractions analyzed with antibody to Ki-67 show that expression of this protein was restricted to nuclear fractions. Western blot analysis for p27Kip1, however, demonstrates in vitro complexes of p27Kip1/Skp2 within both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear fractions.

Demonstration of p27Kip1/Skp2 complexes in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions.

Immunoprecipitation studies demonstrate p27Kip1/Skp2 complexes within nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Subcellular fractions of Jurkat, CEM-6, Raji, and Nalm-6 cells were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal antibody to Skp2 followed by Western blot analysis with anti-p27Kip1. Subcellular fractions analyzed with antibody to Ki-67 show that expression of this protein was restricted to nuclear fractions. Western blot analysis for p27Kip1, however, demonstrates in vitro complexes of p27Kip1/Skp2 within both the cytoplasmic and the nuclear fractions.

Discussion

Reduced levels of p27Kip1 have been associated with malignant transformation and prognosis of a variety of cancers. The p27Kip1 can be down-regulated by several mechanisms. In addition to phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p27Kip1,26 an N-terminal proteolytic processing resulting in a reduced molecular mass of 22 kDa has also been described.27 The F-box protein Skp2 is a component of the ubiquitin protein ligases28,29 that play a critical role in the regulation of G0 to S phase progression.30 The targets of Skp2 include cell cycle proteins such as free cyclin E,18 cyclin D1,31 and p27Kip1.32 Recent studies have shown that Skp2 functions as an oncogene and induces lymphomagenesis in transgenic mice24 as well as malignant transformation of primary rodent fibroblasts.23

A comprehensive study of Skp2 expression in a large series of human malignant lymphoma cell lines and tissues has not been previously reported, although, during the preparation of this manuscript, Latres and coworkers24 reported that Skp2 expression in CLL and DLBCL correlated directly with grade. We have analyzed the expression pattern and levels of Skp2 in 15 hematopoietic cell lines, PBLs as well as a large series of B-lineage NHLs of varying histologic types and proliferation indices. All cell lines expressed Skp2 protein except for the Hodgkin-derived cell lines L428, which expressed negligible levels of both Skp2 and p27Kip.1Most of the cell lines (10 of 15; 67%) demonstrated abundant p27Kip1 protein levels while Skp2 levels were low. In contrast, quiescent PBLs expressed negligible levels of Skp2 even after mitogenic stimulation.

In keeping with the proposed role of Skp2 as a positive regulator of the G1/S transition, our results show that expression of Skp2 was limited largely to the nuclei of proliferating cells. In reactive lymphoid tissues, Skp2 expression was seen within proliferating GC cells and large transformed cells of the interfollicular areas. We found a strong inverse correlation between Skp2 and p27Kip1 expression, with an inverse topographical distribution of these 2 proteins within the reactive lymphoid tissues.

In NHLs, we observed increasing levels of Skp2 with increasing grades of NHL. Low-grade lymphomas (CLL, FCL, and MZL) and most MCLs showed low Skp2 expression (less than 20%). Nine (45%) of aggressive, intermediate-grade DLBCLs and all blastic variants of MCLs demonstrated high Skp2 expression (greater than 20%). Chiarle et al33attributed the low level of p27Kip1 expression in MCL to increased proteasome degradation. Other investigators have attributed the low p27Kip1 expression in MCL and other aggressive B-cell lymphomas to sequestration by cyclin D1 and cyclin D3.11,13 In this study, our aim was to determine whether Skp2 overexpression was associated with decreased p27Kip1expression in aggressive B-cell lymphomas. Our data indicate that in most MCLs, Skp2 expression was low and is thus not the sole determinant of p27Kip1 levels. In blastic MCL and other aggressive B-cell lymphomas, high Skp2 levels are associated with low p27Kip1 levels and may be indicative of ubiquitin-mediated degradation of this protein. In addition to ubiquitin-mediated degradation, other parallel modes of p27Kip1down-regulation have been described. Proteolytic processing of p27Kip127 resulting in a 22-kDa intermediate band may contribute to the reduced p27Kip1 expression in these neoplasms. Indeed, our immunoblot analysis of cell lysates of PBLs revealed a significant protein band of approximately 22 kDa (Figure 1). The absence of this lower-molecular–weight species in the lysates of lymphoma cell lines is of interest, and may be a reflection of the homogeneity of cells in different phases of the cell cycle in lymphoma cell lines relative to those of PBLs. Alternatively, the work of Yaroslavskiy et al34 suggests the presence of a 24-kDa variant p27Kip1 protein expressed in PBLs that is rapidly degraded via a proteasome-mediated mechanism.

Our data suggest that in a large subset of lymphomas, Skp2 may be responsible for the regulation of p27Kip1 levels. This was most evident in low-grade lymphomas, but in DLBCLs the correlation was not as strong. Thus, overexpression of Skp2 may represent an important mechanism in the deregulation of p27Kip1 that contributes to malignant transformation in NHLs. In a subset of lymphomas, high Skp2 protein was not correlated with increased proliferation, suggesting that elevated Skp2 levels are not due merely to increased proliferation and that modulation of Skp2 expression levels may contribute to malignant phenotype without affecting cell proliferation. This finding has also been observed in a subset of oral cancers.23 In those cases in which there was high p27Kip1 and high Skp2 expression, we can postulate that degradation of other proteins, such E2F,22 cyclin D1, B-Myb,35 and cyclin E,19 by Skp2 may be involved in neoplastic transformation.

Previous studies have shown that cytoplasmic displacement of p27Kip1 could potentially abrogate its function as a cdk inhibitor.3,13 Immunoprecipitation data provide support for the physical complexing of Skp2 and p27Kip that was observed in both the nuclear and the cytoplasmic subfractions of 4 cell lines. The significance of this is uncertain, however, since splice variants of Skp2 that result in cytoplasmic localization were found to render it inactive for ubiquitination and degradation of cyclin D1.31 These results suggest that abnormal cellular localization of Skp2 may provide an additional level of regulation of the F-box protein, resulting in deregulated ubiquitin-mediated control of cell cycle progression.

In conclusion, we show that Skp2 expression is strongly correlated with the proliferation index in reactive lymphoid tissues and is expressed primarily in proliferating germinal centers. Among malignant NHLs, low Skp2 protein expression was observed in SLL/CLL and FCL, and was positively correlated with the proliferation index but inversely correlated with p27Kip1 expression. Within aggressive B-cell lymphomas, including MCL and DLBCL, Skp2 levels positively correlated with the proliferation index but did not correlate with p27Kip1 expression. Our findings are in agreement with those reported by Chiarle et al36 and provide evidence for the p27Kip1-degradative function of Skp2 in low-grade B-cell lymphomas, but suggest the existence of other molecular abnormalities in addition to Skp2 in the deregulation of p27Kip1 expression in aggressive lymphomas.

Supported by a grant from the Sunnybrook Trust for Research to M.S.L. and grant CA 83984-01 from the National Institutes of Health to K.S.J.E.-J.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Megan S. Lim, Department of Pathology, University of Utah, 50 North Medical Dr, Rm A 565, Salt Lake City, UT 84132; email: megan.lim@path.utah.edu.

![Fig. 2. Immunohistochemical analysis of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67 expression in reactive lymphoid tissues and malignant lymphoma. / (A) Follicular hyperplasia. Reactive lymph nodes (p27Kip1and Skp2). Expression of p27Kip1 is present in quiescent cells of the follicular mantle zones and interfollicular T lymphocytes. Scattered germinal center centroblasts and interfollicular immunoblasts express Skp2. This staining pattern is similar to that of Ki-67 (data not shown). (B) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/SLL (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Skp2 and Ki-67 expression highlights prolymphocytes and proliferation centers. (C) FCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). A section of low-grade FCL shows intense diffuse reactivity for p27Kip1 in neoplastic and reactive lymphoid cells. Only scattered germinal center cells express Skp2 and Ki-67 relative to p27Kip1. (D) MCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Scattered tumor cells show similar levels of Skp2, p27Kip1, and Ki-67 expression. (E) DLBCL (H&E staining of p27Kip1, Skp2, and Ki-67). Section of intermediate-grade DLBCL shows scattered tumor cells expressing p27Kip1. High levels of Skp2 and Ki-67 expression are seen in DLBCLs. The results show that the expression of Skp2 mirrors that of the proliferation marker Ki-67. (F) Double immunohistochemistry confirms the findings of single-immunolabeling studies. (Reactive lymph nodes shown for SLL/CLL, MZL, DLBCL.) Skp2+cells within proliferating germinal centers of a reactive lymph node are highlighted by the use of pink, whereas the p27Kip1-positive cells within the mantle zones are brown. In a case of SLL/CLL, Skp2+ cells (pink) highlight proliferating immunoblasts within the pseudo-proliferation growth centers. Most of the small neoplastic lymphocytes of SLL/CLL are p27Kip1 positive (brown). In MZL, Skp2+ cells (pink) highlight large centroblasts within a colonized follicle, whereas the surrounding small neoplastic and reactive lymphocytes are p27Kip1 positive (brown). A DLBCL with a high proliferative index shows many Skp2+ cells (pink), with only scattered small reactive lymphocytes and endothelial cells that express p27Kip1 (brown). Original magnification A, ×100; B-F, ×200.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/100/8/10.1182_blood.v100.8.2950/4/m_h82023273002.jpeg?Expires=1765919360&Signature=GJJYJ9BFzToiIsblzIvVJuhVXUH1pKXiTSiH~MkmGg4bGqZsInmfAf17dP-jYGUp08qadHjr6fk~CjwVt0OqDJrTC~eXVUC7vgGA2rXlGmiqo0NOhGwZ~3bOZB16plzFUYrFxVkRW4nYZlQJcpINQ0TxDGhAigYYDUPXoB74vYGLsV~xlSGSl3mNpGfaqtIWedudx-9W4a7we5N4u1xXATOSZgdMmdTMoiqaC900mKGicPdI3KTHWJJ0lUr2WLn1IcdzvAX8ZK1flA~yvs5H-scrrXqOHyALGDEwJ~S5ZQRmQGqC4tzYs64m5I8pjy4V1ES0yroEMfHy3zQnUJJ9Dw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal