Abstract

Tetramers of α- and β-spectrin heterodimers, linked by intermediary proteins to transmembrane proteins, stabilize the red blood cell cytoskeleton. Deficiencies of either α- or β-spectrin can result in severe hereditary spherocytosis (HS) or hereditary elliptocytosis (HE) in mice and humans. Four mouse mutations,sph, sphDem,sph2BC, and sphJ, affect the erythroid α-spectrin gene, Spna1, on chromosome 1 and cause severe HS and HE. Here we describe the molecular alterations in α-spectrin and their consequences insph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJerythrocytes. A splicing mutation, sph2BC initiates the skipping of exon 41 and premature protein termination before the site required for dimerization of α-spectrin with β-spectrin. A nonsense mutation in exon 52, sphJ eliminates the COOH-terminal 13 amino acids. Both defects result in instability of the red cell membrane and loss of membrane surface area. Insph2BC/sph2BC, barely perceptible levels of messenger RNA and consequent decreased synthesis of α-spectrin protein are primarily responsible for the resultant hemolysis. By contrast, sphJ/sphJmice synthesize the truncated α-spectrin in which the 13-terminal amino acids are deleted at higher levels than normal, but they cannot retain this mutant protein in the cytoskeleton. ThesphJdeletion is near the 4.1/actin-binding region at the junctional complex providing new evidence that this 13-amino acid segment at the COOH-terminus of α-spectrin is crucial to the stability of the junctional complex.

Introduction

Mice with mutations in genes encoding membrane skeletal proteins are important models for hereditary spherocytosis (HS).1 Gene mapping and disrupted protein levels2,3 identified the affected product and became the basis for the subsequent cloning and sequencing of α-spectrin(Spna1), β-spectrin (Spnb1), and ankyrin(Ank1) from mouse4-6 and human DNA.7-10 β-Spectrin is a pivotal protein that provides binding sites for ankyrin, the linker between spectrin and the transmembrane protein band 3; α-spectrin heterodimerization; tetramerization of heterodimers11; and 4.1, a protein that joins spectrin tetramers to the transmembrane protein glycophorin C at junctional complexes.12 Anchoring of the spectrin-based cytoskeleton to the transmembrane proteins band 3 and glycophorin C is essential for red blood cell stability. The nucleotide alterations described for the mouse beta spectrin(ja/ja),13 ankyrin(nb/nb),14 and α-spectrin(sph/sph,sphDem/sphDem)4 15mutations provide an explanation for the instability of red cells in these mutants and clues to the functional consequences of alterations in specific amino acids. Assessing functional effects of mutations in humans is more difficult because the secondary genetic diversity affects results, mutations are heterogeneous, and clinical severity may vary among patients with the same mutation.

The murine α-spectrin mutations sph,sph2BC, and sphJ result in severe HS, whereas sphDem is a unique model for hereditary elliptocytosis (HE).16α-Spectrin–deficient mice, such as ja/ja andnb/nb, have severe anemia, reticulocytosis, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and cardiomegaly.1 Mice with a complete lack of α-spectrin, unlike those with no β-spectrin,17 can live to adulthood,18 indicating a less critical role for α-spectrin than β-spectrin. The frequency of thrombosis and stroke, recently described consequences of murine severe hemolytic anemia, is higher (85%-100%) in α-spectrin–deficient mice than in eithernb/nb (15%) or neonatally transfused ja/jamice.19-21

As originally predicted, identification of the mutated site for each allele provides insight into the functional effects of regional alterations or complete ablation of specific cytoskeleton proteins. Murine mutations are maintained on the same genetic background, precluding any effects of modifier genes on their function. Elucidation of primary and secondary effects of the mutations can be performed in vitro and in vivo. The molecular defect in the sph allele is a single-base deletion in exon 11 of Spna1 that causes a frame-shift, a premature termination of α-spectrin mRNA, and an absence of protein.4 InsphDem, an intracisternal A particle element is inserted in intron 10 of the Spna1 gene; exon 11 is skipped with the in-frame deletion of 46 amino acids from the α-spectrin protein.16

Preparatory to further analyses at the cellular level, we have identified the molecular defects in the remaining 2 mutant α-spectrin HS alleles, sph2BC andsphJ, and have characterized functional differences in their red blood cells. Thesph2BC/sph2BC mice generate barely detectable levels of a truncated α-spectrin that lacks the β-spectrin dimerization site. Reticulocytes fromsphJ/sphJ, when compared to +/+, translate higher levels of a truncated α-spectrin lacking the 13 COOH-terminal amino acids. This protein, however, is not stably maintained in the membrane cytoskeleton. This finding enables us to identify a previously unsuspected functional role for this region of α-spectrin in cytoskeletal stabilization, possibly through the regulation of interactions between the spectrin tetramer and junctional complex proteins.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice heterozygous for the sph2BC andsphJ mutations were maintained congenic on both WB/Re (WB) and C57BL/6J (B6) backgrounds. F1 hybrid (WBB6F1)sph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ mice and their normalsph2BC/+, sphJ/+, and +/+ littermates were generated by mating heterozygous WB and B6 mice. Mice were housed and cared for according to Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) specifications.

RT-PCR and sequencing of α-spectrin

Normal phenylhydrazine-treated22 and mutant mice were transcardially perfused with cold 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco/BRL, Grand Island, NY). Total RNA from spleens was isolated using Trizol reagent (Gibco/BRL). Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed as previously described on total spleen RNA from +/+, sph2BC/sph2BC, and sphJ/sphJ mice.4,16Fragments were sequenced by the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method23 using M13 forward and reverse primers and T7 DNA polymerase (TaqFS; ABI, Foster City, CA). Sequence data were analyzed using the Sequencher DNA analysis software package (ABI).

Genomic PCR and sequencing

Isolation and PCR of genomic spleen DNA from +/+,sph2BC/+, andsph2BC/sph2BC mice were performed as previously described.4,16 Genomic PCR products were sequenced and analyzed as described above. Tail DNA PCR was performed in 2 reactions on genomic DNA from +/+,sph2BC/+, and sphJ/+ mice, as described by the manufacturer.24 For thesph2BC mutation, a common downstream primer was used (primer 54, 5′-GTCCTGTGGGTTTATGCCA-3′). Upstream primers detected either only the sph2BC allele (primer 52, 5′-TAGTGGAATCCTGGATAGT-3′) or the wild-type and thesph2BC alleles (primer 53, 5′-GTAGTGGAATCCTGGATAG-3′) of Spna1. ForsphJ, the upstream primer was common (primer 47, 5′-CTCTCACCCCGGAACAA-3′). Downstream primers detected either only thesphJ allele (primer 49, 5′-GTGAAGCCAACATAGTCT-3′) or both the wild-type and thesphJ alleles (primer 50, 5′-TGGTGAAGCCAACATAGTC-3′) of Spna1. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% SeaPlaque-GTG (FMC, Rockland, ME) agarose gels.

Northern blot analyses

Total RNA was extracted from reticulocytes, and spleens were retrieved from normal phenylhydrazine-treated and mutant mice as described above. Northern blot analyses on 5 μg total RNA were performed using the NorthernMax kit and BrightStar Plus membranes (Ambion, Austin, TX). Equivalency of RNA loading was verified by UV shadowing.25 Antisense RNA probe corresponding to nucleotides 7065 to 7322 of the murine erythroid α-spectrin cDNA sequence (GenBank accession no. AF093576) was produced and32P-labeled using the Lig'n'Scribe and StripEZ labeling kits and SP6 RNA polymerase (Ambion). Filters were hybridized at 65°C in NorthernMax hybridization buffer (Ambion). Final filter wash was at 65°C in 0.1 × SSC (sodium chloride/sodium citrate), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses

Red blood cell (RBC) ghosts were prepared from packed red blood cells as previously described.2 Equal amounts of ghost proteins were electrophoresed on 4% stacking/10% separating Laemmli sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels26 or on nongradient gels.27 Duplicate gels were run; one was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and the other transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA).28 Band intensities in Coomassie blue–stained gels were quantified using a Molecular Dynamics Densitometer and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Immunostaining was performed using the Alkaline Phosphatase Conjugate Substrate Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Immunoblots were probed with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to purified mouse erythroid spectrin that reacts equivalently to α- and β-spectrin.2

Osmotic gradient ektacytometry

Fresh blood samples were continuously mixed with a 4% polyvinylpyrrolidone solution of gradually increasing osmolality (60-600 mOsm). The deformability index was recorded as a function of osmolality at a constant applied shear stress of 170 dyne/cm2 using an ektacytometer (Bayer Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY).29

α-Spectrin incorporation into erythrocyte ghosts

Reticulocyte-rich blood was collected in hematocrit tubes from the intraorbital sinus of sphJ/sphJand phenylhydrazine-treated +/+ mice. The tubes were centrifuged in an Autocrit II (Fisher Scientific), and the white blood cell and plasma layers were discarded. Aliquots of 1 × 108 reticulocytes were incubated in 300 μL NCTC-109 (MA Bioproducts, Boston, MA) with 10% fetal calf serum (MA Bioproducts) at 37.5°C in 5% CO2 in air. Cells were labeled by incubation with 50 μCi [35S] methionine or [3H] leucine. Labeled amino acids were chased with 5 mg appropriate cold amino acid. Methionine and leucine were chosen because of the availability of high specific activity preparations and because α-spectrin contains equal molar percentages of each. Under the culture conditions used, incorporation of radiolabel into α-spectrin is continuous in normal and sphJ/sphJ reticulocytes for 70 minutes. Aliquots of cells were removed at various time points during labeling and cold chase. Whole-cell lysates were assayed by immunoprecipitation.30 Ghost proteins were separated on 3.5% Fairbanks SDS-PAGE gels.27 The α-spectrin band was cut from the dried gels and solubilized in NCS tissue solubilizer (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) and Omnifluor (NEN, Boston, MA),31 and the amount of [35S]- and [3H]-labeled α-spectrin was determined by scintillation counting in a Beckman spectrometer.

Results

Identification of the sph2BCmutation

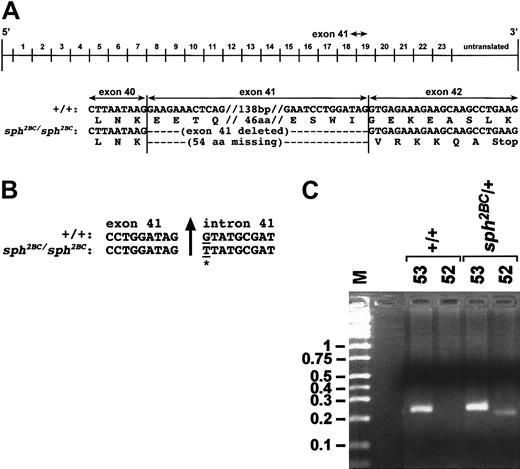

RT-PCR was used to identify the α-spectrin mutation in total RNA from sph2BC/sph2BC spleen. Comparison of cDNA sequence from +/+ andsph2BC/sph2BC mice indicated that exon 41 was absent in the α-spectrin mRNA of the latter (Figure1A). This 162-nucleotide (nt) deletion removes 54 amino acids (aa) from the α-spectrin protein, resulting in a frame-shift and subsequent premature protein termination. No other anomalies were found in the mutant α-spectrin cDNA sequence.

Mutation in sph2BC.

(A) Top, schematic representation of the Spna1 cDNA with numbers above the line corresponding to the repeats of 106 aa that comprise the α-spectrin protein. Exon numbering infers correspondence to the human. Arrow above the line shows the location of exon 41. Shown below the cDNA schematic is nucleotide (top) and amino acid (bottom) sequence of the +/+ andsph2BC/sph2BC cDNAs in the vicinity of the exon 41 skip. Double hatch marks (//) denote sequences not represented in the figure; numbers of base pairs (bp) and amino acids (aa) not represented are shown between the hatch marks. (B) α-Spectrin genomic sequence at the exon 41/intron 41 boundary obtained from spleen DNA of wild-type (+/+) andsph2BC/sph2BC mice. Upward arrow denotes exon 41/intron 41 boundary. The mutated base in thesph2BC allele is marked by an underline and an asterisk. (C) Representative genomic PCR of tail DNA from +/+ andsph2BC/+ mice. Lane M is marker; sizes in kb are shown on left. Lanes labeled 53: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (53 and 54) that amplify wild-type and mutant alleles of Spna1. Lanes labeled 52: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (52 and 54) designed to identify the G→T transition in the sph2BC allele. Genotype of mice is noted above each bracketed pair of reactions.

Mutation in sph2BC.

(A) Top, schematic representation of the Spna1 cDNA with numbers above the line corresponding to the repeats of 106 aa that comprise the α-spectrin protein. Exon numbering infers correspondence to the human. Arrow above the line shows the location of exon 41. Shown below the cDNA schematic is nucleotide (top) and amino acid (bottom) sequence of the +/+ andsph2BC/sph2BC cDNAs in the vicinity of the exon 41 skip. Double hatch marks (//) denote sequences not represented in the figure; numbers of base pairs (bp) and amino acids (aa) not represented are shown between the hatch marks. (B) α-Spectrin genomic sequence at the exon 41/intron 41 boundary obtained from spleen DNA of wild-type (+/+) andsph2BC/sph2BC mice. Upward arrow denotes exon 41/intron 41 boundary. The mutated base in thesph2BC allele is marked by an underline and an asterisk. (C) Representative genomic PCR of tail DNA from +/+ andsph2BC/+ mice. Lane M is marker; sizes in kb are shown on left. Lanes labeled 53: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (53 and 54) that amplify wild-type and mutant alleles of Spna1. Lanes labeled 52: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (52 and 54) designed to identify the G→T transition in the sph2BC allele. Genotype of mice is noted above each bracketed pair of reactions.

Amplification of genomic spleen DNA using exon 41–specific primers showed that exon 41 is present insph2BC/sph2BC mice (data not shown). This suggested a mutation within exon 41 or within flanking introns causes aberrant splicing and the skipping of exon 41 in the mature mRNA. Sequencing of exon 41 and intron 40 from genomic DNA revealed no discrepancies between normal and mutant sequences (data not shown). Sequencing of intron 41 revealed a G-to-T transition in the first base of intron 41 in the sph2BC allele ofSpna1 (Figure 1B). To confirm that this sequence anomaly is the sph2BC mutation, genomic PCR of tail DNA from +/+ and sph2BC/+ mice was performed. PCR with primers designed to identify normal and mutant α-spectrin alleles yields a product in +/+ and sph2BC/+ mice (lanes labeled 53, Figure 1C). Amplification with primers that identify the G-to-T transition is successful only insph2BC/+ mice (lanes labeled 52, Figure 1C). The size difference between the mutant (52) product and the control (53) product is owing to a difference in the length of a CA repeat in intron 41 between the wild-type and the sph2BC alleles of Spna1. Further PCR analyses demonstrated a decreased CA repeat length in the sphJ and wild-type C3HeBFeJ alleles of Spna1, the stock on whichsph2BC originated. This confirms that a change in CA repeat length is a polymorphism and not the actual mutation. No other alterations were detected. We concluded that the G-to-T transition is the sph2BC mutation.

Identification of the sphJmutation

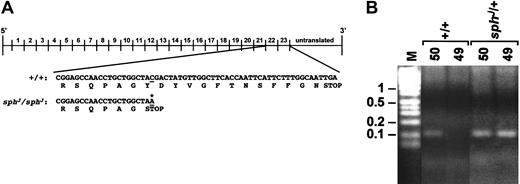

Identification of the sphJ mutation was performed in a similar manner. Analyses of cDNA sequences from +/+ andsphJ/sphJ mice identified a C-to-A transition in exon 52 of thesphJ/sphJ cDNA (Figure2A). This nonsense mutation converts a tyrosine to a stop codon, eliminating the COOH-terminal 13 aa from the protein.

Mutation in sphJ.

(A) Top, schematic representation of the Spna1 cDNA with numbers above the line corresponding to the repeats of 106 aa that comprise the α-spectrin protein. Shown below the cDNA schematic are nucleotide (top) and amino acid (bottom) sequence of the +/+ andsphJ/sphJ cDNAs. (B) Genomic PCR of tail DNA from +/+ and sphJ/+ mice. Lane M is marker; sizes in kb are shown on left. Lanes labeled 50: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (47 and 50) that amplify wild-type and mutant alleles of Spna1. Lanes labeled 50 and 49: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (47 and 49) designed to identify the C→A transition in thesphJ allele. Genotypes of mice are noted above each bracketed pair of reactions.

Mutation in sphJ.

(A) Top, schematic representation of the Spna1 cDNA with numbers above the line corresponding to the repeats of 106 aa that comprise the α-spectrin protein. Shown below the cDNA schematic are nucleotide (top) and amino acid (bottom) sequence of the +/+ andsphJ/sphJ cDNAs. (B) Genomic PCR of tail DNA from +/+ and sphJ/+ mice. Lane M is marker; sizes in kb are shown on left. Lanes labeled 50: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (47 and 50) that amplify wild-type and mutant alleles of Spna1. Lanes labeled 50 and 49: PCR products from a reaction containing primers (47 and 49) designed to identify the C→A transition in thesphJ allele. Genotypes of mice are noted above each bracketed pair of reactions.

The identity of the sphJ mutation was confirmed through genomic PCR of tail DNA from known +/+ andsphJ/+ mice. PCR with primers designed to identify normal and mutant α-spectrin alleles yields a product in +/+ and sphJ/+ mice (lane labeled 50, Figure 2B). Amplification with primers designed to identify the C-to-A transition is successful only in sphJ/+ mice (lanes labeled 49, Figure 2B). These data confirm that the C-to-A transition segregates with the sphJ mutation. The 13 aa deleted as the result of the sphJ mutation include neither the dimerization site nor the EF hands of α-spectrin. Nevertheless, it is clear from the extreme reticulocytosis and dramatically reduced red cell counts18that these 13 aa constitute an important functional domain and are critical to stabilize the cytoskeleton.

Effect of the mutations on RNA and protein levels

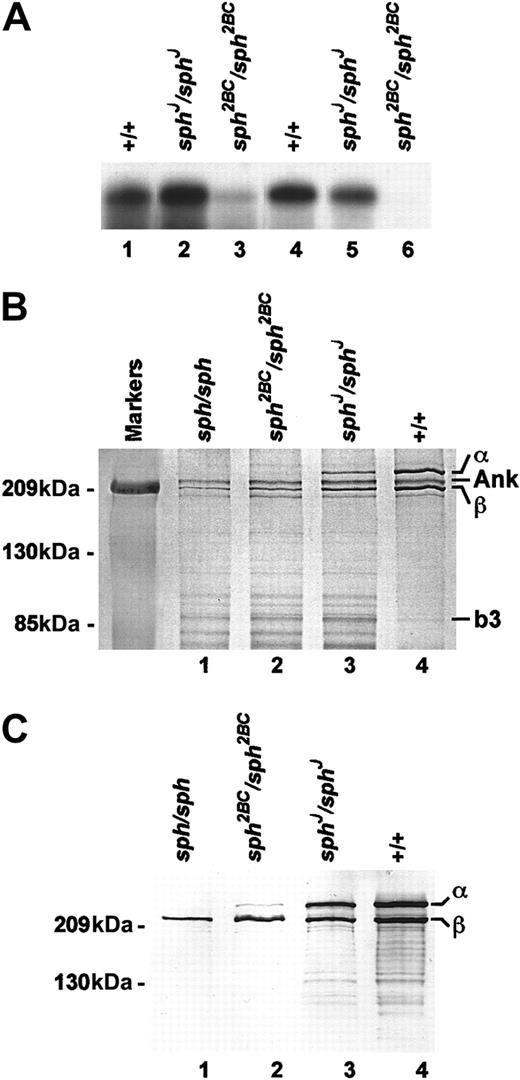

Previously, we showed that erythroid α-spectrin transcript levels in sph2BC/sph2BC spleen, the major site of red blood cell production in the mouse, and reticulocytes are decreased compared with +/+.2 Here we show that the deficiency of sph2BC/sph2BCα-spectrin mRNA is more pronounced in reticulocytes than spleen (Figure 3A), suggesting that the mutant form is unstable and degraded as erythroid precursors mature. By contrast, the erythroid α-spectrin mRNA levels are higher than normal in sphJ/sphJ spleens, though they, too, decrease during maturation. At steady state, α-spectrin insph2BC/sph2BC is not detectable on SDS-PAGE gels of reticulocyte ghosts by Coomassie blue staining, but it is reduced to 20% of normal insphJ/sphJ (Figure 3B). Other cytoskeletal proteins are deficient as well: α-spectrin–band 3 ratios of 0% and 7.7% of normal, β-spectrin–band 3 ratios of 8% and 14% of normal, and ankyrin–band 3 ratios of 20% and 25% of normal in sph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ, respectively (Table1). Immunoblot analyses of RBC ghosts with an antibody that reacts similarly to α- and β-spectrin confirm that α-spectrin is present insphJ/sphJ andsph2BC/sph2BC but not insph/sph (Figure 3C).

Downstream effects of mutations.

(A) Northern blots of total RNA from spleen (lanes 1-3) and reticulocytes (lanes 4-6) of +/+ (lanes 1,4),sphJ/sphJ (lanes 2,5), andsph2BC/sph2BC (lanes 3,6) mice. UV shadowing was used to check RNA loading. (B) Laemmli SDS-PAGE of RBC ghost proteins from +/+ (lane 4) and mutant (lanes 1-3) mice. Genotype of mice is indicated above each lane. Size markers are indicated on the left; relative positions of α-spectrin (α) ankyrin (ANK), β-spectrin (β), and band 3 (b3) are indicated on the right. Ratios of α, ANK, and β to b3 are provided in Table 1. (C) Immunoblot of RBC ghost proteins from +/+ (lane 4) and mutant (lanes 1-3) mice. Genotype of mice is indicated above each lane. Primary antibody (1:250 dilution) detects α and β spectrin equally. Size markers are indicated on the left; relative positions of α and β spectrin are indicated on the right.

Downstream effects of mutations.

(A) Northern blots of total RNA from spleen (lanes 1-3) and reticulocytes (lanes 4-6) of +/+ (lanes 1,4),sphJ/sphJ (lanes 2,5), andsph2BC/sph2BC (lanes 3,6) mice. UV shadowing was used to check RNA loading. (B) Laemmli SDS-PAGE of RBC ghost proteins from +/+ (lane 4) and mutant (lanes 1-3) mice. Genotype of mice is indicated above each lane. Size markers are indicated on the left; relative positions of α-spectrin (α) ankyrin (ANK), β-spectrin (β), and band 3 (b3) are indicated on the right. Ratios of α, ANK, and β to b3 are provided in Table 1. (C) Immunoblot of RBC ghost proteins from +/+ (lane 4) and mutant (lanes 1-3) mice. Genotype of mice is indicated above each lane. Primary antibody (1:250 dilution) detects α and β spectrin equally. Size markers are indicated on the left; relative positions of α and β spectrin are indicated on the right.

Ratios of α-spectrin, ankyrin, and β-spectrin in normal and mutant mice

| Genotype . | α:b3 . | ANK:b3 . | β:b3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBB6F1-sph/sph | 0 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| WBB6F1-sph2BC/sph2BC | 0 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| WBB6F1-sphJ/sphJ | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| WBB6F1-+/+ | 22.0 | 7.9 | 20.0 |

| Genotype . | α:b3 . | ANK:b3 . | β:b3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBB6F1-sph/sph | 0 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| WBB6F1-sph2BC/sph2BC | 0 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| WBB6F1-sphJ/sphJ | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.8 |

| WBB6F1-+/+ | 22.0 | 7.9 | 20.0 |

Values represent densitometry of α-spectrin (α), β-spectrin (β), ankyrin (ANK), and band 3 (b3) on SDS-PAGE (Figure3B).

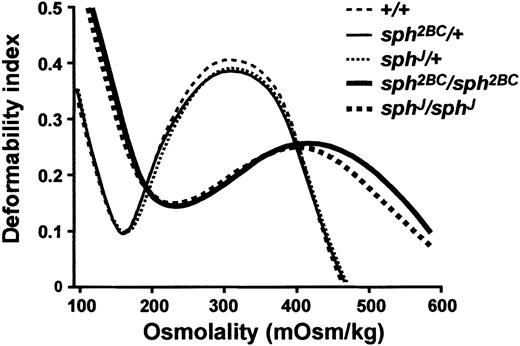

RBC deformability

The instability ofsph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ red blood cells is predicted by their severe microcytic anemia (RBC counts and hematocrits levels are less than 50% of normal) and extremely high levels of compensatory reticulocytosis (90%-95%).2 Heterozygous mice are phenotypically and hematologically normal. Osmotic deformability profiles of blood samples from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (sph2BC/+ andsphJ/+), and homozygous (sph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ) mice are shown in Figure4. The maximum value of the deformability index attained at physiologically relevant osmolality (DImax) is quantitatively related to the mean surface area of the cells.29 The osmolality at which the deformability index reaches a minimum in the hypotonic region of the gradient (Omin) is a measure of the osmotic fragility of the cells. RBCs from heterozygotes do not have significantly different osmotic deformability profiles than wild-type RBCs. In contrast, RBCs fromsph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ mice exhibit a profound decrease in surface area (decreased DImax) and a marked increase in osmotic fragility (increased Omin). The decrease in surface area is consistent with the marked fragmentation of the mutant RBCs seen on peripheral blood smears.32

Osmotic deformability profiles of RBCs from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (sph2BC/+ andsphJ/+), and homozygous (sph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ) mice.

Osmotic deformability profiles of RBCs from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (sph2BC/+ andsphJ/+), and homozygous (sph2BC/sph2BC andsphJ/sphJ) mice.

Membrane attachment ofsphJ/sphJspectrin

Previously, we showed that reticulocytes fromsphJ/sphJ mice synthesize de novo 1.5 times more β-spectrin and 6 times more α-spectrin than reticulocytes from normal mice. In addition, the newly synthesized α-spectrin is incorporated into thesphJ/sphJ membrane at a 6-fold higher rate than normal.30 Despite these observations, only 20% of the normal amount of α-spectrin is present in maturesphJ/sphJ erythrocyte ghosts at steady state. One possible explanation for this is thatsphJ spectrin binds to the membrane skeleton, but the binding is unstable, thereby allowing more rapid turnover of the bound mutant spectrin.

To investigate the possibility that sphJα-spectrin forms a less stable link to the membrane skeleton than normal α-spectrin, a double-label experiment was performed. The experiment was designed to allow [35S]-labeled α-spectrin to enter the soluble α-spectrin pool 30 minutes before the entry of [3H] α-spectrin, allowing us to monitor the displacement of bound [35S]-labeled α-spectrin by [3H]-labeled α-spectrin. Normal andsphJ/sphJ reticulocytes were incubated as follows: 15 minutes with [35S] methionine, 15 minutes with 5 mg/mL cold methionine, 15 minutes with [3H] leucine, and 120 minutes with cold methionine and leucine, 5 mg/mL each. Two washes in basic media were performed between each step.

The ratio of [3H]-to-[35S]–labeled α-spectrin in the membrane skeleton of +/+ andsphJ/sphJ reticulocytes at various times during the 120 minutes chase are shown in Figure5. Data for each time point are the average of 3 experiments and, by being presented as ratios, are internally normalized. It is important to note that the ratio of [3H]/[35S] in the total spectrin pool was the same (0.47) for each genotype at the beginning and at the end of the 120-minute chase. The fact that this ratio remained stable throughout the course of the chase indicates that the α-spectrin pool is relatively stable. As can be seen from the graph, the time required to reach half-equilibrium levels ([3H]/[35S] = 0.41) is 2.3 times faster in sphJ/sphJ than in +/+ cells, suggesting a more rapid turnover of the newly synthesized mutant α-spectrin compared with normal. This result is consistent with thesphJ α-spectrin skeleton link being less stable than normal.

Binding of α-spectrin tosphJ/sphJ and +/+ reticulocyte membranes.

Reticulocyte cultures from each were exposed sequentially for 15-minute intervals to [35S] methionine, unlabeled methionine, and [3H] leucine. During a 2-hour chase in unlabeled methionine and leucine, samples were removed, ghosts made, and the [3H]/[35S] ratios determined from gel-purified α-spectrin. Ratios presented are the averages of 3 experiments (P < .01).

Binding of α-spectrin tosphJ/sphJ and +/+ reticulocyte membranes.

Reticulocyte cultures from each were exposed sequentially for 15-minute intervals to [35S] methionine, unlabeled methionine, and [3H] leucine. During a 2-hour chase in unlabeled methionine and leucine, samples were removed, ghosts made, and the [3H]/[35S] ratios determined from gel-purified α-spectrin. Ratios presented are the averages of 3 experiments (P < .01).

Discussion

Three major conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, thesph2BC and sphJ mutations in Spna1 are molecularly and functionally distinct from each other and from a third severe HS-producing Spna1 mutation,sph, and from the HE-producing Spna1 mutation,sphDem. Second, the splice site mutation in intron 41 of sph2BC is responsible for exon skipping, premature termination, barely detectable protein, and membrane instability of the red cells. Third, the nonsense mutation insphJ that eliminates the C-terminal 0.5% of the protein leads to increased osmotic fragility as a result of the loss of cytoskeleton stability.

The sph2BC mutation is similar to the mutationsphDem in causing exon skipping in the mRNA, but the effects of the exon skip in the 2 mutants are different. InsphDem, the exon skip does not shift the reading frame, and it produces a mutant protein fully capable of incorporation into the cytoskeleton but defective in tetramerization.16In sph2BC, the exon skip introduces a frame-shift and premature termination, resulting in a truncated protein lacking sequences required for dimerization with β-spectrin and incorporation into the membrane; this truncated protein is likely rapidly degraded.33 The presence of the premature stop codon in sph2BC mRNA may activate the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway, leading to rapid turnover of the mutant mRNA.34-36 In this respect,sph2BC more closely resembles the sphmutation, a single base deletion that also leads to premature protein termination and rapid mRNA degradation.4

The location of the sph2BC mutation in murine α-spectrin is comparable to that of the HE-associated LELY mutations of human α-spectrin, a set of 3 linked mutations in exon 40, intron 45, and intron 46.37,38 The intron 45 mutation of αLELY also produces exon skipping,37 as do other mutations located farther 5′ in human α-spectrin, including the HE alleles αDayton, αOran, and αSt. Claude, and the HS allele αPrague.39-42

In contrast to the effects of the sph2BCmutation, the sphJ mutation does not eliminate the dimerization site of α-spectrin.33 In fact, dimerization and tetramerization of the sphJα-spectrin protein can occur, as evidenced by the steady state levels of cytoskeletal proteins prepared from equivalent numbers of +/+ and mutant reticulocytes (Figure 3B) and by a previous study documenting normal dimer-tetramer ratios insphJ/sphJ ghosts.16Despite these findings, sphJ/sphJα-spectrin is unstable in the membrane-bound cytoskeleton (Figure 5and Bodine et al2). The rapid uptake of the radiolabeled protein indicates sites are continuously made available for membrane binding. This would occur if the protein were degraded in situ or were unstably bound. Although we cannot distinguish between these alternatives conclusively, the equivalence of radioisotope in the total spectrin pool at 0 and at 120 minutes after incubation suggests that the pool of α-spectrin remains relatively steady. The more rapid increase of the [3H]/[35S] ratio insphJ/sphJ vs +/+ α-spectrin in the membrane is consistent with a less stable membrane α-spectrin linkage in the mutant. Regardless of the interpretation, the COOH-terminal 13 aa of α-spectrin appear to be critical to its stability in the membrane skeleton because the mature erythrocyte ghosts ofsphJ/sphJ animals contain only 20% of the normal α-spectrin complement.

Structural features of the missing 13 aa suggest ways in which they may contribute to the stability of α-spectrin in the membrane. Four of these 13 aa are potential sites for phosphorylation (2 tyrosines, 1 serine, 1 threonine), and their loss may destabilize binding. To date, only phosphorylation of β-spectrin has been documented in intact RBCs.43

The 13 C-terminal residues are separated from the EF hand motifs of α-spectrin33 by 60 aa; we believe this makes it unlikely that the deletion of these residues in the sphJprotein affects the function of the EF hands. The deleted residues are within the segment of the spectrin tetramer involved in junctional complex (JC) formation.44 To date, studies of interactions of spectrin with JC proteins such as protein 4.1, adducin, and F-actin have identified contact points on β-spectrin but not α-spectrin.44-47 However, several analyses of the spectrin/protein 4.1/actin interaction48-50 have indicated that isolated α- and β-spectrin chains interact with protein 4.1, protein 4.1–mediated binding of spectrin to actin requires the presence of both subunits of spectrin, and the region of β-spectrin that binds actin and protein 4.1 is closely associated with the carboxy terminus of α-spectrin. It is possible the 13 aa deleted insphJ represent a heretofore undiscovered binding site in α-spectrin for JC proteins. Based on the current knowledge of spectrin/JC interactions, we believe it is more likely that this region of α-spectrin is critical in stabilizing the configuration of β-spectrin to promote its binding to JC proteins. Without the interaction with the JC, the spectrin tetramer is tethered to the membrane solely through its ankyrin contacts, which may be insufficient in sphJ/sphJ for spectrin and overall cytoskeleton stability. Further analyses of thesphJ α-spectrin protein and of the 13 deleted amino acids could yield insight into the role of α-spectrin in JC formation and the mechanism through which spectrin stability is disrupted in sphJ/sphJ mice.

We thank reviewers Luanne Peters, Brian Soper, and Babette Gwynn at The Jackson Laboratory. We also thank our colleagues in Microchemical Services, partially supported by a National Cancer Institute core grant, for their excellent expertise.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 8, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0113.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL29305 (J.E.B.), R01 DK26263 (N.M.), NRSA F32 DK09482 (N.J.W.), and core grant CA34196.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Jane E. Barker, The Jackson Laboratory, 600 Main St, Bar Harbor, ME 04609; e-mail: jeb@jax.org.

![Fig. 5. Binding of α-spectrin tosphJ/sphJ and +/+ reticulocyte membranes. / Reticulocyte cultures from each were exposed sequentially for 15-minute intervals to [35S] methionine, unlabeled methionine, and [3H] leucine. During a 2-hour chase in unlabeled methionine and leucine, samples were removed, ghosts made, and the [3H]/[35S] ratios determined from gel-purified α-spectrin. Ratios presented are the averages of 3 experiments (P < .01).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/1/10.1182_blood-2002-01-0113/6/m_h80133590005.jpeg?Expires=1767769604&Signature=YQpHg4OO3aFKwJlEnF9PQFxUHUvm5euP8J2tc1vReav7jGzAmRbeZO2SxZidsrJ3iuaVPs9aFWabvaT82XNgidMi-mNV-qEmSEwK8TPo8CMuW4KCYCiYrpCiCGUKtEcJPRB7xtQJf7pX5LICCM4~9z76JEdLZ3dcgPtwvv5oa01GqhSzde1R6wRC95Cpgot4yDxGa2URjIGKLGDNwtEYyKeHODPt-tXEaBi~Xxvb9p~O-0O4BjOTQMKAQFJuIt2ClFJ3Y8lt-Mx~j-Umyvj78dgjfpo7LUzocRdXSB2-~5xhAVSJrhCOB4DC6KDiW9moXP0AkQMj1pOteYn5r4WhjQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal