Abstract

G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) transduce the signal of a wide variety of chemokines, cytokines, neurotransmitters, hormones, odorants, and others to regulate the biologic homeostasis, including hematopoiesis and immunity. Here we report the molecular cloning of leukocyte-specific STAT-induced GPCR (LSSIG), which is a novel murine orphan GPCR with the highest homology to human GPR43. The mRNA expression of LSSIG was clearly induced in M1 leukemia cells during the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF)–induced differentiation to macrophages, and the induction was evidently signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3)–dependent. GPR43 expression was also strongly induced in HL-60 and U937 leukemia cells during the differentiation to monocytes. Further analysis showed that the expression of both LSSIG and GPR43 is highly restricted in hematopoietic tissues. Cytokine-stimulation induced LSSIG and GPR43 in bone marrow cells, and monocytes and neutrophils, respectively. These results suggest that LSSIG and GPR43 might play pivotal roles in differentiation and immune response of monocytes and granulocytes.

Introduction

G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) comprise the largest superfamily of transmembrane receptors in the human genome and couple to second messenger signaling cascade mechanism through G-proteins. Remarkably, they have been most targeted in pharmaceutical research.1,2 Human genome analysis indicated that, excluding sensory receptors, about 150 GPCRs are orphan receptors whose ligands have not yet been discovered.3

Murine M1 myeloid leukemia cells differentiate into macrophages upon stimulation of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) or interleukin-6 (IL-6). LIF and IL-6 bind gp130 and activate the JAK/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) pathway, where STAT3 plays a central role in transmitting the signals from the membrane to the nucleus.4 While several lines of evidence indicate that STAT3 activation is indispensable for the differentiation of M1 cells, the precise mechanisms have not been clarified.5 6

To identify the new molecules that would be induced in M1 cells by LIF stimulation, we have performed representational difference analysis (RDA).7,8 We have already cloned Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator9 and BATF17 using this system. Here we report a novel possible GPCR that was induced in a STAT3-dependent manner in LIF-stimulated M1 cells. As the expression of this gene was restricted in leukocytes, we named this gene leukocyte-specific STAT-induced GPCR (LSSIG). LSSIG and its possible human counterpart, GPR43,10 are similarly expressed in leucocytes, and their expression was enhanced by cytokine and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation, suggesting a possible role of these receptors in leukocyte activation and differentiation.

Study design

Cells and reagents

M1 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% horse serum. M1/Y705F was established as described previously.9 M1/STAT3ER was established by introduction of a retrovirus vector pMXneo/STAT3ER and subsequent selection by neomycin.11 Human peripheral blood was obtained from healthy adult volunteers. Monocytes were negatively selected using StemSep system (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada),12 and neutrophils were prepared by Mono-Poly resolving medium (Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan).13 IL-6 (50 ng/mL; Strathmann Biotec, Hannover, Germany), LIF (5 ng/mL; Strathmann Biotec), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (100 ng/mL; gift from Kirin Brewer, Gunma, Japan), interleukin-4 (20 ng/mL; Sigma, St Louis, MO), interleukin-8 (100 ng/mL) (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), interleukin-3 (5 ng/mL) (Genzyme), LPS (1 μg/mL) (Sigma), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (16 nM; Sigma), and 4-hydroxytamoxifen (2μM; Sigma) were used for the stimulation. Soluble IL-6 receptor (100 ng/mL; R&D, Minneapolis, MN) was added when cells were stimulated with IL-6. Six-week-old Std-ddY mice (Japan SLC) were used for preparing splenocytes, bone marrow cells, and peritoneal macrophages. For the collection of macrophages, the thioglycollate medium (Sigma) was injected into the peritoneal cavity of mice 4 days before harvesting. Approval was obtained from the review board of Nagoya University for this study. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

RDA and Northern blot analysis

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Two-step reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), and the data were analyzed by ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System (Foster City, CA). Sequences of forward and reverse primers for GPR43 are 5′ggctttccccgtgcagtac3′ and 5′ccagagctgcaatcactcca3′, respectively.

Results and discussion

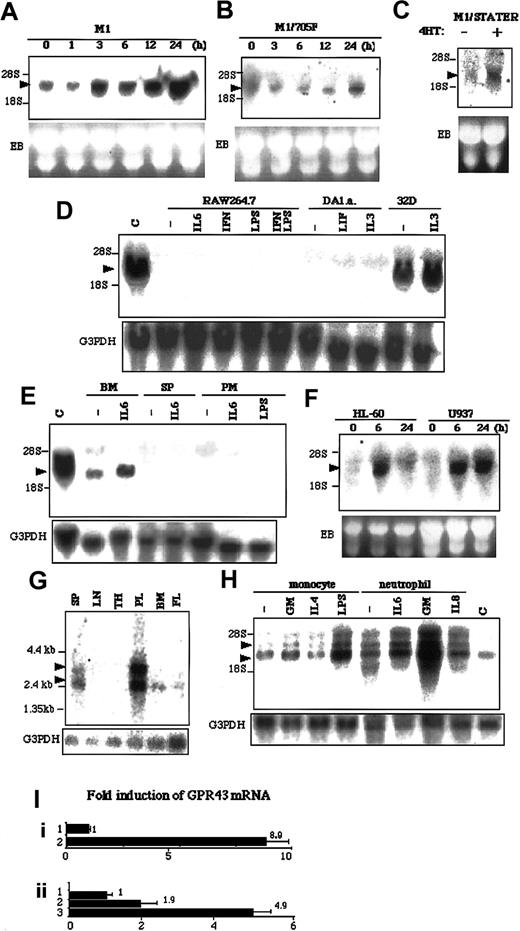

By applying RDA to LIF-simulated M1 cells, we cloned a novel gene, LSSIG, which encoded 330 amino acids (Genebank accession no. AF545043). Homology analysis showed that LSSIG shared 82% nucleotides identity and 85% amino acids identity with a human possible orphan GPCR, GPR 43 (Figure 1). To confirm that LSSIG is induced in M1 cells upon LIF-stimulation, we examined its expression by Northern blot analysis. LSSIG mRNA was induced 3 hours after the stimulation and increased until 48 hours (Figure2A and data not shown). Interferon γ (IFNγ), which also activates STAT3 in M1 cells, similarly induced the LSSIG expression (data not shown). To investigate whether the induction of LSSIG depends on STAT3 activation, we analyzed its induction in M1/Y705F cells that express dominant negative form of STAT3 (Y705F). In M1/Y705F (Figure 2B), the induction was obviously reduced. We also produced M1 cell lines that expressed STAT3 fused with estrogen receptor (M1/STAT3ER). STAT3ER is conditionally active when stimulated with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4HT).14 Stimulation of M1/STAT3ER with 4HT induced LSSIG (Figure 2C), while no induction was observed in M1 cells (data not shown). These data would strongly suggest that the induction of LSSIG is dependent on the activation of the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway.

Alignment of LSSIG deduced amino acid sequence with GPR43.

Shaded box residues indicate residues conserved between LSSIG and GPR43. Possible transmembrane (TM1-7) regions are underlined.

Alignment of LSSIG deduced amino acid sequence with GPR43.

Shaded box residues indicate residues conserved between LSSIG and GPR43. Possible transmembrane (TM1-7) regions are underlined.

mRNA expression of LSSIG and GPR43.

(A-H) Northern blot analysis. The membrane was hybridized with the probes of LSSIG (A-E) and GPR43 (F-H). M1 (A) and M1/Y705F (B) cells were stimulated with LIF for the indicated time. (C) M1/STAT3ER cells were stimulated with 4HT for 3 hours. (D) Several cell lines were stimulated for 3 hours with IL-6, interferon γ (IFNγ), LPS, IFNγ plus LPS, LIF, or IL-3. DA1.a and 32D cells were starved for cytokines for 5 hours and were stimulated. C: M1 cells stimulated with LIF for 24 hours as a control. (E) Murine hematopoietic tissues were stimulated for 3 hours. Bone marrow cells (BM), spleen cells (SP), and peritoneal macrophages (PM) were stimulated with IL-6 or LPS. C: M1 cells stimulated with LIF for 24 hours as a control. (F) HL-60 and U937 cells were stimulated with PMA for the indicated time. (G) Human tissue blot. SP, spleen; LN, lymph nodes; TH, thymus; PL, peripheral blood leukocytes; BM, bone marrow; FL, fetal liver. In each lane, 2 μg polyA+RNA was blotted. (H) Human monocytes and neutrophils were stimulated for 3 hours with GM-CSF (GM), IL-4, LPS, or IL-8. C: U937 cells were stimulated with PMA for 6 hours as a control. (The transcripts are indicated by arrowheads. EB indicates ethidium bromide staining of gel; G3PDH, the same membrane reblotted with the probe of G3PDH. Similar results were obtained in more than 3 independent experiments.) (I) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of GPR43 expression in U937 cells (i) and human monocytes (ii). (i) 1, nonstimulated; 2, stimulated with PMA for 24 hours. (ii) 1, nonstimulated; 2, stimulated with GM-CSF for 3 hours; 3, stimulated with LPS for 3 hours. Values were corrected by the data of RT-PCR for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase and represent means of 3 samples. The error bars represent the standard deviations.

mRNA expression of LSSIG and GPR43.

(A-H) Northern blot analysis. The membrane was hybridized with the probes of LSSIG (A-E) and GPR43 (F-H). M1 (A) and M1/Y705F (B) cells were stimulated with LIF for the indicated time. (C) M1/STAT3ER cells were stimulated with 4HT for 3 hours. (D) Several cell lines were stimulated for 3 hours with IL-6, interferon γ (IFNγ), LPS, IFNγ plus LPS, LIF, or IL-3. DA1.a and 32D cells were starved for cytokines for 5 hours and were stimulated. C: M1 cells stimulated with LIF for 24 hours as a control. (E) Murine hematopoietic tissues were stimulated for 3 hours. Bone marrow cells (BM), spleen cells (SP), and peritoneal macrophages (PM) were stimulated with IL-6 or LPS. C: M1 cells stimulated with LIF for 24 hours as a control. (F) HL-60 and U937 cells were stimulated with PMA for the indicated time. (G) Human tissue blot. SP, spleen; LN, lymph nodes; TH, thymus; PL, peripheral blood leukocytes; BM, bone marrow; FL, fetal liver. In each lane, 2 μg polyA+RNA was blotted. (H) Human monocytes and neutrophils were stimulated for 3 hours with GM-CSF (GM), IL-4, LPS, or IL-8. C: U937 cells were stimulated with PMA for 6 hours as a control. (The transcripts are indicated by arrowheads. EB indicates ethidium bromide staining of gel; G3PDH, the same membrane reblotted with the probe of G3PDH. Similar results were obtained in more than 3 independent experiments.) (I) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of GPR43 expression in U937 cells (i) and human monocytes (ii). (i) 1, nonstimulated; 2, stimulated with PMA for 24 hours. (ii) 1, nonstimulated; 2, stimulated with GM-CSF for 3 hours; 3, stimulated with LPS for 3 hours. Values were corrected by the data of RT-PCR for glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase and represent means of 3 samples. The error bars represent the standard deviations.

Then, we examined the expression of LSSIG in several murine hematopoietic cell lines. Although IL-3–dependent 32D myeloid cells expressed the abundant transcript of LSSIG, RAW264.7 macrophage cells and IL-3-and LIF-dependent DA1.a lymphoid cells did not express LSSIG, even if stimulated with cytokines or LPS (Figure 2D). Hence, the expression of LSSIG seemed highly cell-type specific. No expression of LSSIG was detected in murine lung, heart, skeletal muscle, brain, kidney, stomach, small intestine, liver, ovary, testis, uterus, placenta, fetus (E18), thymus, and lymph nodes (data not shown). As far as we examined, bone marrow cells expressed LSSIG, which was enhanced by the stimulation of IL-6. In contrast, spleen and peritoneal macrophage cells did not express it even if stimulated (Figure 2E). These results suggest that LSSIG would be expressed at certain stages of myeloid lineage other than lymphocytes and mature macrophages.

Although Sawzdargo et al identified GPR43, a possible human homolog of LSSIG, its expression and function have not yet been documented.10 We examined its expression in phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)–stimulated HL-60 human promyeloid leukemia cells and U937 promonocytic leukemia cells. These cells have been known to differentiate into monocytes/macrophages by PMA stimulation.15 16 As shown in Figure 2F, the expression of GPR43 was sharply induced 6 hours after stimulation in both cells. Together, these data further imply that LSSIG and GPR43 would be involved in the physiological process of differentiation to monocytes/macrophages and strongly support the idea that GPR43 is a human counterpart of LSSIG.

Consistent with this notion, GPR43 was strongly expressed in peripheral leukocytes and weakly in spleen cells, bone marrow cells and fetal liver, whereas no message was detected in lymph nodes and thymus (Figure 2G). Peripheral leukocytes expressed an extra larger transcript, which may be linked to cell maturation (Figure 2G). Then we isolated human monocytes and neutrophils and examined the expression of GPR43. Both nonstimulated cells expressed GPR43 at a high level (Figure2H). In monocytes, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and, especially, LPS enhanced the expression, whereas interleukin-4 (IL-4) did not induce it. (Figure 2H). In neutrophils, IL-6 and GM-CSF induced the expression, although the effect of GM-CSF was much stronger (Figure 2H). Furthermore, we performed quantitative RT-PCR analysis using GPR43-specific primers in U937 cells and monocytes. PCR analysis also demonstrated that the transcript of GPR43 increased by stimulation (Figure 2I). This profile of activation of leukocytes suggests the possibility that the expression of GPR43 might be enhanced in innate immunity.

The obvious induction of GPR43 by GM-CSF suggests that the activation not only of STAT3 but also of STAT5 might regulate it. On the other hand, STAT6, a signaling molecule downstream of IL-4 receptor, does not seem to induce it. Moreover, the induction of GPR43 by PMA and LPS implies that GPR43 is induced through a variety of signaling pathways.

Taken as a whole, we propose LSSIG and its human counterpart, GPR43, as initiates that would be involved in leukocyte differentiation and host defense. To our knowledge, LSSIG is the first GPCR whose expression was proven to be regulated by JAK/STAT3 pathway. Identifying their functional ligands could bring us a fascinating tool to regulate hematopoietic disorders.

We thank Dr Toshio Hirano for STAT3 plasmid, Dr Tetsuya Matsuguchi for RAW264.7 cells, Dr Masayuki Towatari for HL-60 and U937 cells, Dr Yasuhiko Miyata for helpful suggestions, and Misa Sato for technical assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 19, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1881.

Supported by Grant-in-Aids for Center of Excellence (COE) Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan and for Scientific Research of Japan Society for Promotion of Science.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Takashi Iwamoto, Radioisotope Research Center Medical Division, Nagoya University School of Medicine, 65 Tsurumai-cho, Showa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 466-8550, Japan; e-mail:iwamoto@med.nagoya-u.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal