Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were designed to target thebcr-abl oncogene, which causes chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and bcr-abl–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Chemically synthesized anti–bcr-abl siRNAs were selected using reporter gene constructs and were found to reduce bcr-abl mRNA up to 87% in bcr-abl–positive cell lines and in primary cells from CML patients. This mRNA reduction was specific for bcr-abl because c-abl and c-bcr mRNA levels remained unaffected. Furthermore, protein expression of BCR-ABL and of laminA/C was reduced by specific siRNAs up to 80% in bcr-abl–positive and normal CD34+ cells, respectively. Finally, anti–bcr-abl siRNA inhibited BCR-ABL–dependent, but not cytokine-dependent, proliferation in a bcr-abl–positive cell line. These data demonstrate that siRNA can specifically and efficiently interfere with the expression of an oncogenic fusion gene in hematopoietic cells.

Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) describes a highly conserved regulatory mechanism that mediates sequence-specific posttranscriptional gene silencing initiated by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA).1-3 The RNase III enzyme Dicer processes dsRNA into approximately 22-nucleotide (nt) small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)4 that serve as guide sequences to induce target-specific mRNA cleavage by the RNA-induced silencing complex RISC.5 In plants andCaenorhabditis elegans, RNAi may involve the amplification of dsRNA by an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP),6 and it enables systemic, long-term, and heritable gene silencing. In contrast, RNAi in Drosophila and mammals seems cell autonomous, transient, and nonheritable. Because exogenous application of siRNAs can efficiently trigger RNAi in mammalian cells,7,8 siRNAs are increasingly used in transient (co)transfection assays to modulate gene expression in mammalian cells, including human cells.9-12

Fusion transcripts encoding oncogenic proteins may represent potential targets for a tumor-specific RNAi approach. The Philadelphia (Ph) translocation t(9;22)(q34;q11) generates the bcr-abl fusion gene characteristic for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).13 Bcr-abl encodes a constitutively active cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase that is necessary and sufficient to induce and maintain leukemic transformation.14-16

We demonstrate that anti–bcr-abl siRNAs specifically inhibit bcr-abl mRNA expression in hematopoietic cell lines and primary CML cells. They reduce BCR-ABL protein expression and inhibit BCR-ABL–dependent, but not cytokine-dependent, cell proliferation. Therefore, anti–bcr-abl siRNAs may allow further analysis of BCR-ABL functions and, eventually, may lead to RNAi-based therapeutics.

Study design

siRNAs

Twenty-one–nucleotide single-stranded RNAs directed against the fusion sequence of bcr-abl were chemically synthesized (BioSpring, Frankfurt, Germany) (Figure 1A). The sense and antisense sequences were: b3a2_1, 5′-GCAGAGUUCAAAAGCCCUUdTdT-3′; b3a2_3, 5′-AGCAGAGUUCAAAAGCCCUdTdT-3′; and b3a2_1, 5′-AAGGGCUUUUGAACUCUGCdTdT-3′; b3a2_3, 5′-AGGGCUUUUGAACUCUGCUdTdT-3′, respectively. Control anti-GL2_ and invGL2_siRNAs targeting GL2-luciferase, anti–laminA/C siRNAs, and siRNA duplexes were generated as described by Elbashir et al.7

RNA interference in hematopoietic cells.

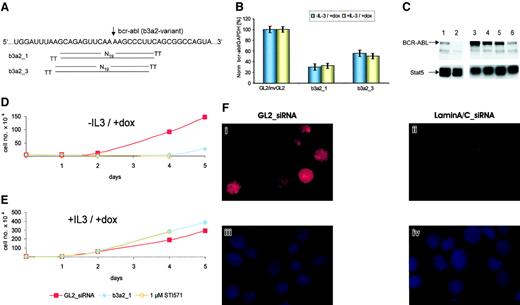

(A) Bcr-abl fusion sequence and schematic representation of b3a2_1 and b3a2_3 siRNAs shifted by only one nucleotide. TT indicates the deoxythymidine dimer as 3' overhang. The arrow marks the fusion between bcr (left) and abl (right) sequences of the b3a2–bcr-abl variant. (B) siRNA mediated the reduction of bcr-abl mRNA expression in TonB cells in the presence or absence of IL-3. Normalized bcr-abl/GAPDH mRNA levels were measured 24 hours after electroporation and are shown compared with control cells treated with GL2/invGL2 control siRNAs (100%). The data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot of TonB cells treated with doxycycline and siRNAs. TonB cells were induced to express BCR-ABL (lanes 1, 3-6) or not (lane 2) by the addition of doxycycline at 1 μg/mL. Cells were electroporated with b3a2_1 siRNA (lanes 4, 6) or control GL2_siRNA (lanes 3, 5) and were lysed 24 (lanes 3-4) and 60 hours (lanes 5-6) after electroporation, respectively. The upper panel shows an immunoblot with anti-BCR–specific antibodies, and the lower panel shows the same membrane reprobed with anti-Stat5 antibodies as loading control. (D-E) Effects of siRNAs on BCR-ABL–mediated (D) and IL-3–mediated (E) cell proliferation. TonB cells were either electroporated with control GL2_ (red squares) or b3a2_1 (blue-filled circles) siRNA or were left untreated in cultures containing 1 μM STI571 (orange open circles). Viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion during suspension cultures after the addition of doxycycline at 1 μg/mL without (D) or with (E) murine IL-3. Cell numbers of b3a2_1- and STI571-treated cells were nearly identical in the presence or absence of IL-3. (F) Inhibition of laminA/C protein expression by siRNAs in normal CD34+ cells. Normal CD34+cells were electroporated with control GL2_ (i,iii) or anti–laminA/C siRNAs (ii,iv). Panels i-ii show immunostaining of laminA/C, and panels iii-iv show nuclear chromatin staining with DAPI (4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-2HCl) stain.

RNA interference in hematopoietic cells.

(A) Bcr-abl fusion sequence and schematic representation of b3a2_1 and b3a2_3 siRNAs shifted by only one nucleotide. TT indicates the deoxythymidine dimer as 3' overhang. The arrow marks the fusion between bcr (left) and abl (right) sequences of the b3a2–bcr-abl variant. (B) siRNA mediated the reduction of bcr-abl mRNA expression in TonB cells in the presence or absence of IL-3. Normalized bcr-abl/GAPDH mRNA levels were measured 24 hours after electroporation and are shown compared with control cells treated with GL2/invGL2 control siRNAs (100%). The data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot of TonB cells treated with doxycycline and siRNAs. TonB cells were induced to express BCR-ABL (lanes 1, 3-6) or not (lane 2) by the addition of doxycycline at 1 μg/mL. Cells were electroporated with b3a2_1 siRNA (lanes 4, 6) or control GL2_siRNA (lanes 3, 5) and were lysed 24 (lanes 3-4) and 60 hours (lanes 5-6) after electroporation, respectively. The upper panel shows an immunoblot with anti-BCR–specific antibodies, and the lower panel shows the same membrane reprobed with anti-Stat5 antibodies as loading control. (D-E) Effects of siRNAs on BCR-ABL–mediated (D) and IL-3–mediated (E) cell proliferation. TonB cells were either electroporated with control GL2_ (red squares) or b3a2_1 (blue-filled circles) siRNA or were left untreated in cultures containing 1 μM STI571 (orange open circles). Viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion during suspension cultures after the addition of doxycycline at 1 μg/mL without (D) or with (E) murine IL-3. Cell numbers of b3a2_1- and STI571-treated cells were nearly identical in the presence or absence of IL-3. (F) Inhibition of laminA/C protein expression by siRNAs in normal CD34+ cells. Normal CD34+cells were electroporated with control GL2_ (i,iii) or anti–laminA/C siRNAs (ii,iv). Panels i-ii show immunostaining of laminA/C, and panels iii-iv show nuclear chromatin staining with DAPI (4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-2HCl) stain.

Transfection of hematopoietic cells

K562, murine TonB cells derived from the BaF3 cell line, and primary hematopoietic cells were cultured as described.17-19 Cells (1 × 106) were electroporated (330 V, 10 ms) in 100 μL RPMI 1640/10% fetal calf serum (FCS) containing 0.5 μg siRNA duplex in a 4-mm electroporation cuvette using an EPI 2500 gene pulser (Fischer, Heidelberg, Germany).

Real-time RT-PCR

Real-time Taqman reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed as described20 21 with the probes and primers: bcrFP, 5′-AGCACGGACAGACTCATGGG-3′; bcrRP, 5′-GCTGCCAGTCTCTGTCCTGC-3′; bcr-Taqman-probe, 5′-AGGGCCAGGTCCAGCTGGACCC-3′ covering the exon b5/b6 boundary; ablFP, 5′-GGCTGTCCTCGTCCTCCAG-3′; ablRP, 5′-TCAGACCCTGAGGCTCAAAGT-3′; abl-Taqman-probe, 5′-ATCTGGAAGAAGCCCTTCAGCGGC-3′ covering the exon 1a/2 boundary. RNA from murine TonB cells was digested with DNase I and analyzed using the probe and primers: GAPDHmu 5′, 5′-CAACAGGGTGGTGGACCTC-3′; GAPDHmu3′, 5′-GGGTGGTCCAGGGTTTCTTA-3′; and GAPDHmu-Taqman probe, 5′-TGGCCTACATGGCCTCCAAGGA-3′.

Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence microscopy

Cellular lysates from TonB cells were immunoblotted with polyclonal anti-bcr antibody (N-20) and polyclonal anti-Stat5 antibody (C-17) as described.18 To quantify transduction efficacy, laminA/C immunostaining was performed using a monoclonal anti–laminA/C antibody (sc-7292; all antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) as described.7

Primary normal and CML cells

Normal and CML CD34+ cells were purified to 95% or more, as described.19 Primary CD34+ cells or peripheral blood–derived mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) were cultured in X-VIVO/1% human serum albumin (HSA) with recombinant human stem cell factor (SCF; 100 ng/mL), Flt-3-ligand (100 ng/mL), and thrombopoietin (TPO; 20 ng/mL) before electroporation, and granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-3 (IL-3) (10 ng/mL each) were added thereafter. Methylcellulose colony assays were performed as described.19

Results and discussion

Selection of anti–bcr-abl siRNAs

Efficient siRNAs targeted against the b3a2-fusion sequence of bcr-abl were selected by cotransfection with a chimeric bcr-abl–enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP) reporter gene in HeLa cells. HeLa cells could be transfected up to 95% (data not shown). Of 4 chemically synthesized 21-nt siRNAs tested, b3a2_1 and b3a2_3 (Figure 1A) were the most efficient. They reduced the number of fluorescent cells (to 90%), bcr-abl-EGFP mRNA levels (to 87%), and fluorescence intensity per cell (up to 100-fold) 24 hours after transfection (data not shown). RNAi was specific because no reduction in fluorescence intensity was found with control siRNAs or when native EGFP without bcr-abl sequences was used as reporter. Furthermore, anti–b3a2–bcr-abl siRNA only reduced the b3a2-, but not the b2a2-, variant of a bcr-abl-EGFP reporter gene and vice versa (data not shown).

Effects of siRNAs in hematopoietic cell lines

The siRNAs b3a2_1 and b3a2_3 were tested in Ph+ K562 and TonB cells expressing bcr-abl under the control of a doxycycline-inducible promoter.17 Transfection efficacy was analyzed using the laminA/C system and reached approximately 80% in K562 cells (data not shown). After 24 and 48 hours, b3a2_1 and b3a2_3, but not control siRNAs, reduced bcr-abl mRNA levels up to 24.8% and 35.2% (b3a2_1) and 32.4% and 61% (b3a2_3), respectively (Tables 1 and2 and data not shown). Notably, c-bcr and c-abl mRNA levels remained unaffected, demonstrating the specificity of anti–bcr-abl siRNAs (Tables 1-2). Furthermore, b3a2_1 and b3a2_3 transiently reduced the number of viable K562 cells by 75% in suspension cultures 4 days after electroporation (data not shown).

Effects of anti-bcr-abl siRNAs on bcr-abl mRNA expression in bcr-abl-positive cells

| Cell sample/siRNA . | bcr-abl/GAPDH, % . | c-bcr/GAPDH, % . | c-abl/GAPDH, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| K562 cells | |||

| GL2 | 99.7 ± 2.1 | 82.0 ± 13 | 97.5 ± 2.5 |

| GL2_inv | 98.0 ± 2.1 | 116 ± 13 | 102 ± 2.5 |

| b3a2_1 | 24.8 ± 3.7 | 98.0 ± 2.5 | 95.0 ± 10 |

| b3a2_3 | 32.4 ± 1.2 | 99.5 ± 2.2 | 109 ± 1.5 |

| CML-PBMNCs | |||

| GL2 | 100 | ND | ND |

| b3a2_1 | |||

| No. 1 | 21 | ND | ND |

| No. 2 | 45 | ND | ND |

| No. 3 | 46 | ND | ND |

| No. 4 | 45 | ND | ND |

| CML-CD34+cells | |||

| GL2 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| b3a2_1 | |||

| No. 5 | 22 | 102 | 98 |

| No. 6 | 50 | 104 | 92 |

| Cell sample/siRNA . | bcr-abl/GAPDH, % . | c-bcr/GAPDH, % . | c-abl/GAPDH, % . |

|---|---|---|---|

| K562 cells | |||

| GL2 | 99.7 ± 2.1 | 82.0 ± 13 | 97.5 ± 2.5 |

| GL2_inv | 98.0 ± 2.1 | 116 ± 13 | 102 ± 2.5 |

| b3a2_1 | 24.8 ± 3.7 | 98.0 ± 2.5 | 95.0 ± 10 |

| b3a2_3 | 32.4 ± 1.2 | 99.5 ± 2.2 | 109 ± 1.5 |

| CML-PBMNCs | |||

| GL2 | 100 | ND | ND |

| b3a2_1 | |||

| No. 1 | 21 | ND | ND |

| No. 2 | 45 | ND | ND |

| No. 3 | 46 | ND | ND |

| No. 4 | 45 | ND | ND |

| CML-CD34+cells | |||

| GL2 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| b3a2_1 | |||

| No. 5 | 22 | 102 | 98 |

| No. 6 | 50 | 104 | 92 |

The data represent normalized bcr-abl, c-bcr, and c-abl values from K562 cells, primary PBMNCs, and purified CD34+ CML cells 24 hours after electroporation with the respective siRNAs. GL2-siRNA controls (GL2) for each patient were set at 100%. K562 data represent mean ± SD from 4 independent experiments.

ND indicates not done.

Effects of anti-bcr-abl siRNAs on colony formation of primary CML cells

| Cell sample/siRNA . | CFU-GM . | BFU-E . |

|---|---|---|

| CML-PBMNCs | ||

| No. 1 | ||

| GL2 | 7 | 15 |

| b3a2_1 | 7 | 13 |

| No. 2 | ||

| GL2 | 45 | 64 |

| b3a2_1 | 43 | 43 |

| No. 3 | ||

| GL2 | 5 | 2 |

| b3a2_1 | 3 | 1 |

| No. 4 | ||

| GL2 | 23 | 53 |

| b3a2_1 | 22 | 45 |

| CML-CD34+ cells | ||

| No. 5 | ||

| GL2 | 30 | 17 |

| b3a2_1 | 32 | 17 |

| No STI571 | 29 | 14 |

| 1 μM STI571 | 4 | 2 |

| No. 5 | ||

| GL2 | 139 | 62 |

| b3a2_1 | 132 | 68 |

| No. 6 | ||

| GL2 | 128 | 72 |

| b3a2_1 | 88 | 66 |

| Cell sample/siRNA . | CFU-GM . | BFU-E . |

|---|---|---|

| CML-PBMNCs | ||

| No. 1 | ||

| GL2 | 7 | 15 |

| b3a2_1 | 7 | 13 |

| No. 2 | ||

| GL2 | 45 | 64 |

| b3a2_1 | 43 | 43 |

| No. 3 | ||

| GL2 | 5 | 2 |

| b3a2_1 | 3 | 1 |

| No. 4 | ||

| GL2 | 23 | 53 |

| b3a2_1 | 22 | 45 |

| CML-CD34+ cells | ||

| No. 5 | ||

| GL2 | 30 | 17 |

| b3a2_1 | 32 | 17 |

| No STI571 | 29 | 14 |

| 1 μM STI571 | 4 | 2 |

| No. 5 | ||

| GL2 | 139 | 62 |

| b3a2_1 | 132 | 68 |

| No. 6 | ||

| GL2 | 128 | 72 |

| b3a2_1 | 88 | 66 |

Standard colony assays were performed with PBMNCs (patient samples 1-4) after electroporation with the respective siRNA. Purified CD34+ cells from patient sample 5 were initially cultured in standard colony assays, and the samples “No STI571” and “1 μM STI571” were not electroporated. The last 4 lanes show CD34+ cells (patient samples 5, 6) first grown in suspension culture for 3 days and then plated into standard colony assays. No viable cells were found after suspension culture in the presence of 1 μM STI571 after 3 days (patient sample 5).

CFU-GM indicates colony-forming unit granulocyte macrophage; and BFU-E, burst-forming unit erythroid.

Cultures of TonB cells with or without doxycycline and IL-3 allow separate studies of BCR-ABL– and IL-3–mediated cell proliferation, with factor-independent proliferation considered as a surrogate marker for cellular transformation. After electroporation with b3a2_1 siRNA, bcr-abl mRNA declined by approximately 70% independent of IL-3 (Figure1B). Furthermore, b3a2_1 siRNA reduced BCR-ABL protein expression by approximately 55%, as analyzed by immunoblotting and densitometry (Figure 1C). Finally, b3a2_1 siRNA reduced the number of viable TonB cells to an extent similar to that for the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in the absence, but not in the presence, of IL-3 (Figure 1D-E). Again, cultures of TonB cells treated with b3a2_1 resumed growth after 3 to 5 days in all conditions tested. In parental bcr-abl–negative BaF3 cells, siRNA had no effect on cell proliferation (data not shown).

siRNA activity in primary hematopoietic cells

siRNA efficacy in primary hematopoietic cells was first demonstrated in normal CD34+ cells using the laminA/C system. Anti–laminA/C siRNA reduced laminA/C protein expression by approximately 70% (Figure 1F). Next, electroporation of PBMNCs or purified CD34+ cells from 6 CML patients with b3a2_1 siRNA reduced bcr-abl mRNA levels by 50% to 79% compared with control siRNA (100%) (Table 1). Again, c-bcr and c-abl mRNA levels remained unchanged in both CML samples studied. When primary CML cells were transfected with b3a2_1 siRNA and grown in cytokine-supplemented liquid or semisolid cultures, no significant inhibition of cell proliferation or colony formation was observed (Table 2 and data not shown). In contrast, STI571 markedly reduced the number of viable cells in suspension cultures and the colony number derived from purified CD34+ cells, as shown in earlier studies22(Table 2 and data not shown).

Our data show gene suppression mediated by siRNA in normal and malignant hematopoietic cells. Specifically, siRNAs induced a specific but transient reduction of bcr-abl mRNA and protein expression, and an inhibition of BCR-ABL–mediated cell proliferation. As expected for mammalian cells,2,3,23 we found no evidence for transitive RNAi involving RdRP because anti–bcr-abl siRNAs did not affect c-bcr and c-abl mRNA levels. The markedly different effects of anti–bcr-abl siRNA and STI571 on CML cells in our study may be explained by the transient and nonheritable nature of RNAi in mammalian cells and the protein half-life of BCR-ABL. Alternatively, the inhibition of bcr-abl expression by siRNA or antisense sequences24 compared with blocking BCR-ABL kinase activity by STI571 may induce different phenotypes in cytokine-supplemented cultures of bcr-abl–positive cells.22,24 The molecular basis for these differences, and the kinetics of RNAi triggered by exogenous or endogenous expression of siRNAs,10 25 should be analyzed to better define the role of RNAi as scientific tools or potential therapeutics in human hematopoietic cells.

We thank George Daley (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA) for providing us with the TonB cell line used in this study. We thank Michael Morgan for critical reading of the manuscript and J. Deinhardt for help with the densitometric analysis.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 26, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1685.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Michaela Scherr or Matthias Eder, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Zentrum Innere Medizin, Abteilung Hämatologie und Onkologie, Carl-Neuberg Strasse 1, D-30625 Hannover, Germany; e-mail: m.scherr@t-online.de oreder.matthias@mh-hannover.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal