Previous studies in murine bone marrow transplantation (BMT) models using neutralizing anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antibodies or TNF receptor (TNFR)–deficient recipients have demonstrated that TNF can be involved in both graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and graft-versus-leukemia (GVL). TNF in these GVHD and GVL models was thought to be primarily produced by activated monocytes and macrophages, and the role of T cell–derived TNF was not determined. We used TNF−/− mice to study the specific role of TNF produced by donor T cells in a well-established parent-into-F1 hybrid model (C57BL/6J→C3FeB6F1/J). Recipients of TNF−/− T cells developed significantly less morbidity and mortality from GVHD than recipients of wild-type (wt) T cells. Histology of GVHD target organs revealed significantly less damage in thymus, small bowel, and large bowel, but not in liver or skin tissues from recipients of TNF−/− T cells. Recipients of TNF−/−T cells which were also inoculated with leukemia cells at the time of BMT showed increased mortality from leukemia when compared with recipients of wt cells. We found that TNF−/− T cells do not have intrinsic defects in vitro or in vivo in proliferation, IFN-γ production, or alloactivation. We could not detect TNF in the serum of our transplant recipients, suggesting that T cells contribute to GVHD and GVL via membrane-bound or locally released TNF.

Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is the original member of what is now known as the TNF superfamily. Signaling through 2 different receptors (TNFR1 or p55TNFR and TNFR2 or p75TNFR), it modulates complex events in malignant growth, infection, inflammation, and immunity. As a type I inflammatory cytokine, TNF has an important role in the pathophysiology of a variety of inflammatory diseases.1 The inhibition of TNF has emerged as an effective novel therapy for a number of autoimmune diseases.1-3 Although TNF can be expressed in a membrane-anchored form and secreted by activated T cells,4the specific role of T cell–derived TNF (as opposed to TNF derived from monocytes/macrophages or natural killer [NK] cells) in inflammatory disease models has been less well studied.

The role of TNF as an effector molecule of cytotoxic T cells is poorly defined. Although most of the cytolytic activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTL) can be accounted for by the classic pathways of perforin/granzyme and Fas/FasL, CTLs deficient for both pathways exhibit residual cytolytic activity,5 which has been ascribed to TNF in its membrane-anchored or secreted form.

TNF has been recognized as an important inflammatory cytokine of the “cytokine storm,” which is an important element in the pathogenesis of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).6 In murine BMT models, blockade of the TNF pathway with anti-TNF antibodies or by using TNF receptor-deficient recipients has resulted in diminished GVHD and graft-versus-leukemia (GVL).7-9 Serum TNF levels have been reported to be elevated in patients with acute GVHD and clinical trials have shown improvement of GVHD during treatment with anti-TNF antibodies.10 11

Previous murine studies demonstrated an important role for TNF in the development of GVHD and the GVL effect. It was presumed that most of the TNF responsible for GVHD and GVL activity was derived from host or donor monocytes/macrophages due to the pretransplantation conditioning regimen and GVHD, although the experiments using anti-TNF antibodies or TNF receptor–deficient recipients could not distinguish between different sources of TNF. In this study we decided to examine the specific role of donor T cell–derived TNF in GVHD, and GVL, which had not been addressed before.

Using wild-type (wt) and TNF−/− donor T cells in a well-established murine parent-into-F1 model of major histocompatibility (MHC) antigen-mismatched BMT, C57BL/6J (H-2b)-into-C3FeB6F1/J (H-2b/k), we found evidence for a significant contribution of donor T cell–derived TNF to morbidity and mortality from GVHD as well as to GVL activity.

Materials and methods

Cell line and antibodies

32Dp210 (H-2k) is a myeloid leukemia cell line derived from 32Dc13 cells (of C3H/HeJ mouse origin) that were transfected with the p210 bcr/abl oncogene.12Cell culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μM 2-Mercaptoethanol.

Antimurine CD16/CD32 Fc block (2.4G2) and fluorochrome-labeled antimurine CD3 (145-2C11), antimurine CD4 (RM4-5), antimurine CD8 (53-6.7), antimurine CD62L (MEL-14), antimurine CD122 (TM-B1), antimurine CD25 (PC61), antimurine Ly-9.1 (30C7), antimurine CD45R/B220 (RA3-6B2), antimurine CD90.2 (53-2.1), antimurine CD44 (IM7), antimurine TNF (MP6-XT22) and antimurine IFN-γ (XMG1.2) antibodies were obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Mice and BMT

Female C57BL/6J (“B6,” H-2b) and C3FeB6F1/J (“C3HxB6,” H-2b/k) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and female C57BL/6J.TNF−/−(“TNF−/−”) mice were kindly provided by the New York Branch of The Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research13 and used in BMT experiments between 8 and 10 weeks of age. BMT protocols were approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Bone marrow (BM) cells were removed aseptically from femurs and tibias. Donor BM was T-cell depleted by using anti–Thy-1.2 antibody and low–TOX-M rabbit complement (Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, Canada). Splenic T cells were obtained by purification over a nylon wool column. CD4+ T cells were obtained by further purification through negative selection with anti-CD8 antibodies (53-6.7) and anti-CD45R (RA3-6B2) coupled to microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Cells (5 × 106 BM cells with or without splenic T cells) were resuspended in Dulbecco modified essential medium and transplanted by tail-vein infusion into lethally irradiated recipients on day 0. Prior to transplantation, recipients received on day 0 1300 cGy total body irradiation (137Cs source) as a split dose with 3 hours between doses. Mice were housed in the specific pathogen-free facility of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in sterilized micro-isolator cages and received normal chow and autoclaved hyperchlorinated drinking water (pH 3.0).

Leukemia induction, assessment of leukemic death vs death from GVHD, and GVHD organ pathology

Animals received 2 × 104 32Dp210 cells intravenously in a separate injection on day 0 of BMT. Survival was monitored daily, and ear-tagged animals in coded cages were individually scored weekly for 5 clinical parameters (weight loss, hunched posture, decreased activity, fur ruffling, and skin lesions) on a scale from 0 to 2. A clinical GVHD score was generated by summation of the 5 criteria scores (0-10) as first described by Cooke et al.14 Every animal that died during the course of the experiment underwent autopsy and the cause of each death after BMT was determined as previously described15,19: (1) any spleen weight of more than 0.3 g (a previously determined cut-off point that never occurs with GVHD alone) or (2) a spleen weight of less than 0.3 g with evidence of leukemic infiltration on histopathology of the liver and spleen (obtained from every animal with a spleen weight of < 0.3 g and reviewed by veterinary pathologist Dr Hai Nguyen, Cornell University, New York, NY) were considered death from leukemia. In addition, the weekly determined GVHD scores correlated with death from GVHD. GVHD target organ pathology for bowel (terminal ileum and ascending colon), liver and skin (tongue and ear) was asessed by one individual (J.M.C. for liver and intestinal pathology, G.F.M. for cutaneous pathology) in a blinded fashion on formalin-preserved, paraffin-embedded and hematoxylin/eosin-stained histopathology sections with a semiquantitative scoring system. Briefly, bowel and liver were scored for 19 to 22 different parameters associated with GVHD as previously described16,17 and skin was evaluated for the number of dyskeratotic and apoptotic cells as previously published.18

Flow cytometric analysis, intracellular cytokine staining, and CFSE staining

Splenocytes were washed, incubated with CD16/CD32 Fc block, subsequently incubated with primary antibodies, washed, resuspended and analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). For intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were initially incubated in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) with irradiated (2000 cGy) allogeneic (C3HxB6) stimulator cells for 5 days, then harvested, and restimulated for 15 hours with either allogeneic or syngeneic irradiated stimulator cells (T-cell depleted, to reduce contamination with cytokine-expressing stimulator cells) in the presence of Brefeldin A (10 μg/mL; Sigma, St Louis, MO). Alternatively (in an attempt to measure cytokine production of in vivo preactivated cells), splenic donor T cells were harvested from recipients of allogeneic BMT (wt B6 TCD-BM + 2 × 106 splenic T cells into lethally irradiated C3HxB6) on day 14 and subsequently restimulated for 15 hours with irradiated (2000 cGy) syngeneic (B6) or allogeneic (C3HxB6) TCD stimulators. Subsequently, cells were washed, stained with primary (surface) fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies, fixed and permeabilized with the Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit (Pharmingen), and stained with secondary (intracellular cytokine) PE-conjugated antibody. Activated CD4+ memory cells were gated as CD4+, CD44+, and CD62L−; CD8+ memory cells were gated as CD8+, CD44+, CD122+. FACS analysis was carried out as described above. For CFSE staining, RBC-lysed splenocytes of B6 wt and TNF−/− background were positively selected with anti-CD5 microbeads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA), stained in 2.5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and 25 × 106 of stained cells were transplanted into allogeneic (C3HxB6) recipients. Splenocytes from these animals were harvested 72 hours later, stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for surface antigens and FACS analysis was carried out as above.

Proliferation assays

To measure proliferation in response to mitogen, RBC-lysed B6 splenocytes of wt or TNF−/− origin (3 individual animals per group) were incubated (in quadruplicates for each condition per animal) in 96-well plates at 2 × 105 cells per well in complete cell culture medium (as described above) ± 2.5 μg/mL Concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma) for 72 hours. For the last 20 hours of the incubation 1 μCi/well (0.037 MBq/well) of H-3-thymidine (NEN, Boston, MA) was added. Cells were harvested with a Filtermate 196 harvester (Packard, Meriden, CT), fixed with 70% Ethanol, and H-3-thymidine incorporation was measured on a Topcount NXT microscintillation counter (Packard, Meriden, CT) after the addition of scintillation fluid (“Microscint-20”; Packard). Fold increase over incubation with medium alone was calculated for each animal, and average and SE for 3 animals per group is shown. To measure proliferation in response to alloantigen, effector cells were prepared as described in the previous paragraph and incubated for 96 hours in the presence of allogeneic (C3HxB6) or syngeneic (B6) irradiated (2000 cGy) RBC-lysed splenocytes. The effector-to-stimulator ratio was 1:2. H-3-thymidine incorporation was measured as described before.

ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for serum IFN-γ and TNF levels was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions with 2 different assay kits from R&D (Minneapolis, MN) and Endogen (Woburn, MA), with similar results.

Statistics

Statistical analysis of GVHD scores, thymocyte and splenocyte number, and proliferation assays was performed with the nonparametric unpaired Mann-Whitney U test, whereas the Mantel-Cox log-rank test was used for survival data. A P value of .05 or less was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

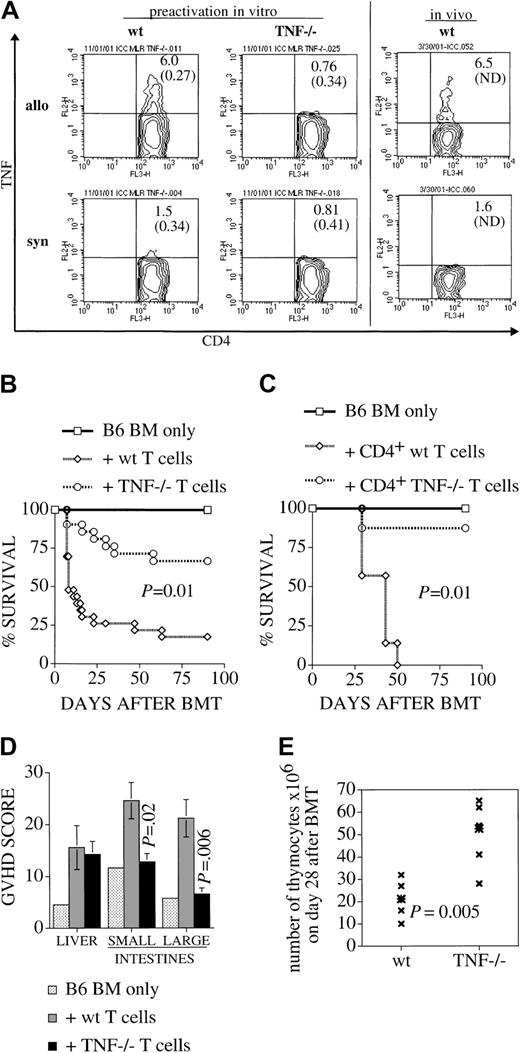

TNF is expressed upon alloactivation of wt but not TNF−/− T cells

We measured intracellular cytokine expression to examine whether TNF is expressed upon alloactivation of T cells. A significant percentage of activated memory CD4+ T cells, whether preactivated in an allogeneic MLR or in vivo as donor T cells in an allogeneic transplant, were found to express TNF during a 15-hour secondary coincubation with irradiated allogeneic stimulators (Figure1A). This number decreased to close to (isotype control) background, when the secondary coincubation was with syngeneic stimulators; remaining positive cells in this setting are due to the primary allogeneic stimulus. We also verified with this method the null status of our TNF−/− T cells: when used as effectors in this assay, they were unable to express TNF in response to allogeneic stimuli (Figure 1A; < 0.5% positive cells in this setting are likely to be due to some residual cytokine-secreting T cells in the TCD stimulator population). Similar results were obtained when the CD122+/CD44+ population of activated/memory CD8+ cells was gated (data not shown). The percentage of TNF-secreting activated/memory cells is in the typical range that we have shown previously in similar settings.19

Alloactivated wt (but not TNF−/−) T cells express TNF. TNF is required for maximum GVHD induction, and for target organ damage in thymus, small and large bowel, but not liver.

(A) B6 splenocytes of wt or TNF−/− origin (pooled from 4 animals per group) were coincubated in a primary MLR with irradiated allogeneic (C3HxB6) stimulator cells for 5 days, then harvested, and restimulated for 15 hours with allogeneic or syngeneic irradiated stimulator cells (T-cell depleted, to reduce contamination with cytokine expressing stimulator cells) in the presence of Brefeldin A. All cells (“allo” and “syn”) are initially stimulated with allogeneic stimulators for 5 days for technical reasons (syngeneic “stimulation” does not yield viable cells after 5 days). Only for overnight restimulation on day 5 are responder cells divided into allo- or syngeneic secondary stimulation in the presence of Brefeldin A. This explains the small remaining fraction of IFN-γ–expressing cells in the syngeneic control group. The 2 panels on the right side show a similar analysis of splenocytes that were harvested on day 14 after BMT (from recipients which had received allogeneic TCD-BM and T cells), and subsequently restimulated in vitro as described above. Cells were then stained for intracellular TNF. Populations shown are gated for CD4+, CD44+, and CD62L−. Percentages of TNF-expressing cells are indicated (followed by percentage of isotype-control positive cells in parentheses). One experiment representative of 4 separate experiments is shown. (B,C) Lethally irradiated C3HxB6 mice were given transplants of B6 TCD BM with or without the addition of (B) 2 × 106splenic T cells or (C) 1 × 106 purified splenic CD4+ T cells from B6 wt or TNF−/− mice. Survival from GVHD was monitored and plotted as a Kaplan-Meier curve. Groups consisted of 4 animals for the BM-only control group and 7 to 15 animals for the groups receiving T cells. (D-E) C3HxB6 recipients given transplants as described in (A) were killed on day 28 and organs were harvested. (D) Liver, small bowel, and large bowel were analyzed in a blinded fashion with a semiquantitative GVHD scoring system as described. Higher scores indicate more severe GVHD organ damage. (E) Thymi of the same animals were dispersed and total thymocyte number was recorded.

Alloactivated wt (but not TNF−/−) T cells express TNF. TNF is required for maximum GVHD induction, and for target organ damage in thymus, small and large bowel, but not liver.

(A) B6 splenocytes of wt or TNF−/− origin (pooled from 4 animals per group) were coincubated in a primary MLR with irradiated allogeneic (C3HxB6) stimulator cells for 5 days, then harvested, and restimulated for 15 hours with allogeneic or syngeneic irradiated stimulator cells (T-cell depleted, to reduce contamination with cytokine expressing stimulator cells) in the presence of Brefeldin A. All cells (“allo” and “syn”) are initially stimulated with allogeneic stimulators for 5 days for technical reasons (syngeneic “stimulation” does not yield viable cells after 5 days). Only for overnight restimulation on day 5 are responder cells divided into allo- or syngeneic secondary stimulation in the presence of Brefeldin A. This explains the small remaining fraction of IFN-γ–expressing cells in the syngeneic control group. The 2 panels on the right side show a similar analysis of splenocytes that were harvested on day 14 after BMT (from recipients which had received allogeneic TCD-BM and T cells), and subsequently restimulated in vitro as described above. Cells were then stained for intracellular TNF. Populations shown are gated for CD4+, CD44+, and CD62L−. Percentages of TNF-expressing cells are indicated (followed by percentage of isotype-control positive cells in parentheses). One experiment representative of 4 separate experiments is shown. (B,C) Lethally irradiated C3HxB6 mice were given transplants of B6 TCD BM with or without the addition of (B) 2 × 106splenic T cells or (C) 1 × 106 purified splenic CD4+ T cells from B6 wt or TNF−/− mice. Survival from GVHD was monitored and plotted as a Kaplan-Meier curve. Groups consisted of 4 animals for the BM-only control group and 7 to 15 animals for the groups receiving T cells. (D-E) C3HxB6 recipients given transplants as described in (A) were killed on day 28 and organs were harvested. (D) Liver, small bowel, and large bowel were analyzed in a blinded fashion with a semiquantitative GVHD scoring system as described. Higher scores indicate more severe GVHD organ damage. (E) Thymi of the same animals were dispersed and total thymocyte number was recorded.

Donor T cells and CD4+ T cells require TNF for maximum GVHD induction

To assess the importance of donor T cell–derived TNF in the development of GVHD, we used splenic T cells from TNF-deficient B6 mice (TNF−/−) as donor T cells in a well-established murine parent-into-F1 model (mismatched for MHC classes I and II): B6-into-C3HxB6. Lethally irradiated C3HxB6 recipients all received T cell–depleted (TCD) bone marrow (BM) from wt B6 mice and only the source of the donor T-cell inoculum (wt or TNF−/−) differed between groups. Recipients of wt T cells demonstrated greater morbidity (weight loss and clinical GVHD score) (data not shown) and significantly greater mortality than recipients of TNF−/−T cells (Figure 1B). Because we had previously shown that induction of GVHD in this model is modulated primarily by donor CD4+ T cells,19 we also tested the contribution of TNF to GVHD induced with a highly purified CD4+ donor cell inoculum (Figure 1C). Again, we saw a profound effect of donor T cell–derived TNF on mortality from GVHD. More than 80% of animals receiving TNF−/− cells survived past day 100, whereas all animals receiving wt CD 4 cells died of GVHD by day 50. This is in agreement with data from studies using TNF receptor–deficient recipients8 or administration of anti-TNF antibodies after BMT,7,9,17,20 which also showed a reduction of mortality from GVHD with blockade of the TNF pathway (in some studies this effect occurred only with higher radiation doses17 21). However, these studies were not able to determine the source of TNF that was responsible for induction of GVHD. It was thought that TNF is released mainly from damaged or activated host macrophages. Although our data do not exclude the possibility that host macrophage–derived TNF also contributes to the pathophysiology of GVHD, in our model we are able to show a major role of donor T cell–derived TNF, with experimental groups differing exclusively in TNF status of donor T cells.

Small and large bowel as well as thymus, but not liver, are target organs of TNF-mediated GVHD

To determine the contribution of TNF to specific GVHD-associated target organ pathology, recipients of wt and TNF−/− T cells were killed on day 28 after BMT and organs were harvested. When small bowel and large bowel histopathology was assessed with a semiquantitative score that has previously been validated in human and experimental GVHD,16,17 recipients of wt T cells had significant small and large bowel GVHD, whereas the intestinal GVHD scores in recipients of TNF−/− T cells were similar to those of controls, which had received only TCD-BM (Figure 1D). The total body irradiation that is administered to all animals (including controls) is responsible for some baseline histological damage, which is reflected in the low scores of control animals. These data suggest that donor T cell–derived TNF plays an important role in intestinal GVHD. Liver pathology on the other hand was not significantly different between animals receiving wt vs. TNF−/− cells. This pattern of target organ GVHD is consistent with observations by Piguet et al,22 Hattori et al7 and Cooke et al20 who administered monoclonal anti-TNF antibody and found amelioration of intestinal GVHD, whereas liver GVHD has been found to be mediated mostly through Fas/FasL.7,23 The use of antibodies in these studies resulted in blockade of any TNF/TNF receptor interaction, without discriminating between different sources of TNF, and could have resulted in a broader inhibition of TNF than in our studies. We and others24,25 have previously demonstrated that thymic GVHD is associated with a decrease in thymic cellularity. Here we found significantly higher thymic cellularity in recipients of TNF−/− T cells than in recipients of wt T cells (Figure 1E), indicating that TNF contributes to thymic GVHD. We also analyzed on day 28 after BMT skin GVHD in recipients of wt and TNF−/− cells and found levels of skin GVHD which did not significantly differ between groups (data not shown). This would suggest that donor T cell–derived TNF is not required for skin GVHD. Previous studies using anti-TNF antibodies found a decrease in skin GVHD7 22 and these results in combination with our data would suggest that the TNF which is involved in skin GVHD is not derived from donor T cells but other effector cells of donor or host origin. In conclusion, our data indicate the relevance of TNF originating from the donor T cell for overall mortality and morbidity, as well as for GVHD-associated intestinal and thymic pathology.

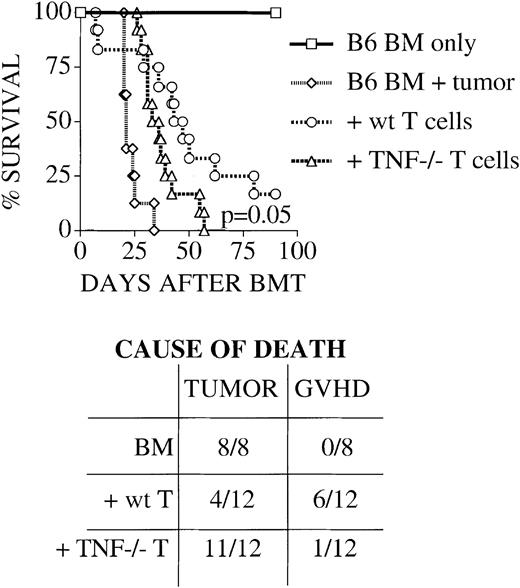

TNF is required for graft-versus-leukemia activity of donor T cells

In allogeneic BMT, donor T cells are not only the cause of GVHD, they are also important effectors of a graft-versus-leukemia effect.26 The perforin/granzyme and to a lesser degree the Fas/FasL pathway have been found by us and others to be important mediators of this effect.9,19 To test the relevance of TNF as an additional donor T cell effector pathway for graft-versus-leukemia activity, we inoculated BMT recipients at the time of transplantation with 32Dp210 cells (a murine leukemia cell line derived by transfection of the human bcr/abl oncogene into a murine myeloid cell line of H-2k background12) and monitored survival from leukemia and/or GVHD. We found that mice, which received bone marrow without the addition of T cells, succumbed rapidly to leukemia as expected (Figure 2). Recipients of wt T cells survived significantly longer, with most of the mortality due to GVHD and not leukemic death (see table insert in Figure 2). Recipients of TNF−/− T cells died significantly earlier than recipients of wt T cells and almost exclusively from leukemia, indicating that donor T cell–derived TNF is an important effector of graft-versus-tumor (GVT) activity. Previous studies using anti-TNF antibody had demonstrated increased leukemic relapse when this pathway was blocked, but again could not determine what the source of the TNF was.9,21 Hill et al21 also demonstrated an increased rate of leukemic death when donor T cells lacked the p55TNFR, suggesting that TNF signals via this receptor on donor T cells for optimal CTL generation. Our study suggests another, more direct mechanism for TNF-mediated GVL activity: Donor T cells use soluble or membrane-anchored TNF to exert their antileukemic activity.

TNF is required for maximum graft-versus leukemia activity of donor T cells.

Lethally irradiated C3HxB6 mice were given transplants as described in “Materials and methods” with B6 TCD BM with or without the addition of 2 × 106 splenic T cells from B6 wt or TNF−/− mice. Some animals also received 2 × 104 32Dp210 murine leukemia cells on day 0. Survival was monitored daily and cause of death is determined by necropsy as described in “Materials and methods.” Groups consisted of 4 (BM-only group) and 8 to 12 (all other groups) animals per group. Survival is plotted as a Kaplan-Meier curve. Recipients of wt T cells survive longer, and die mostly of GVHD, while recipients of bone marrow (BM) only and of BM + TNF−/− T cells succumb rapidly to tumor, indicating an important role for donor T cell–derived TNF in GVL activity.

TNF is required for maximum graft-versus leukemia activity of donor T cells.

Lethally irradiated C3HxB6 mice were given transplants as described in “Materials and methods” with B6 TCD BM with or without the addition of 2 × 106 splenic T cells from B6 wt or TNF−/− mice. Some animals also received 2 × 104 32Dp210 murine leukemia cells on day 0. Survival was monitored daily and cause of death is determined by necropsy as described in “Materials and methods.” Groups consisted of 4 (BM-only group) and 8 to 12 (all other groups) animals per group. Survival is plotted as a Kaplan-Meier curve. Recipients of wt T cells survive longer, and die mostly of GVHD, while recipients of bone marrow (BM) only and of BM + TNF−/− T cells succumb rapidly to tumor, indicating an important role for donor T cell–derived TNF in GVL activity.

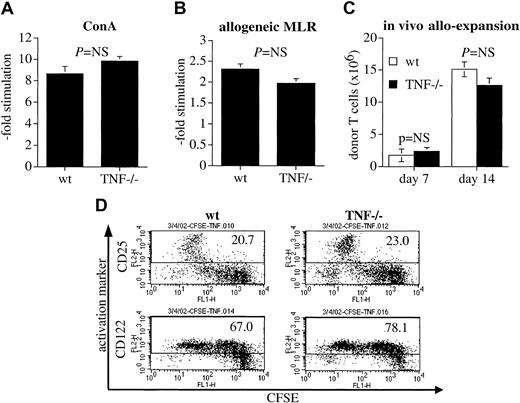

Decreased GVHD and GVL activity of TNF−/− T cells is not due to intrinsic defects in proliferation, activation, or IFN-γ secretion, but is likely due to lack of TNF as a local effector molecule utilized by T cells in target organs

The decreased ability of TNF−/− T cells to induce GVHD could be due to impaired proliferation of these alloreactive cells. To test this hypothesis, we compared the ability of TNF−/− T cells to proliferate in response to allogeneic stimulation in vitro and in vivo. TNF−/− T cells did not differ significantly in their ability to proliferate in response to ConA (Figure 3A) or in a 5-day MLR with irradiated allogeneic C3HxB6 stimulator cells (Figure 3B). Equally, when we compared the number of splenic T cells of donor origin on day 7 and day 14 in recipients of donor TCD-BM and T cells, we found no significant difference between animals that had received wt T cells and animals that had received TNF-deficient T cells (Figure 3C). To test for differences in activation status of TNF−/− T cells, we stained in vivo allo-activated CD8+ T cells (which were also CFSE stained so that their early divisions could be tracked) with CD25 and CD122 and found the same pattern of up-regulation of CD25 and CD122 over the course of the first divisions in both TNF−/− and wt cells (Figure 3D). Similar data were obtained in CD4+ T cells (not shown). Finally, we examined IFN-γ secretion in vitro on a per cell basis (Table1) as well as in vivo serum levels after BMT (Table 2).

TNF−/− T cells do not have intrinsic defects in their proliferative capability and ability to be alloactivated.

(A) Splenocytes were incubated in quadruplicate wells for 72 hours in the presence of ConA. Proliferation over the last 20 hours was measured by H-3-thymidine incorporation and is expressed as -fold increase over controls without ConA. The mean ± SE for 3 animals per group is shown. (B) Splenocytes from preimmunized B6 wt or TNF−/−animals were incubated for 96 hours in quadruplicate wells in the presence of allogeneic (C3HxB6) irradiated splenocytes as stimulators. Proliferation over the last 20 hours was measured by H-3-thymidine incorporation and is expressed as fold increase over incubation with irradiated syngeneic (B6) controls. The mean ± SE for one representative experiment (of 2 total) with 3 animals per group is shown. (C) C3HxB6 recipients of allogeneic (B6) TCD wt BM (5 × 106 cells) and wt or TNF−/− splenic T cells (2 × 106) were killed on days 7 and 14 after BMT. Total splenocytes were counted and donor T cells were determined by flow cytometry for Ly9.1 and CD3. The mean ± SE of one representative experiment (of 3 total) with 4 animals per group is shown. (D) C3HxB6 recipients were given transplants of TCD wt B6 BM and a high dose (25 × 106) of CFSE-stained wt or TNF−/− T cells. Spleens were harvested 72 hours later and multicolor flow cytometric analysis was performed. CD25 and CD 122 expression in CD8+ cells is shown. Percentages of CD25 and CD122-expressing cells are indicated. One experiment representative of 2 separate experiments is shown.

TNF−/− T cells do not have intrinsic defects in their proliferative capability and ability to be alloactivated.

(A) Splenocytes were incubated in quadruplicate wells for 72 hours in the presence of ConA. Proliferation over the last 20 hours was measured by H-3-thymidine incorporation and is expressed as -fold increase over controls without ConA. The mean ± SE for 3 animals per group is shown. (B) Splenocytes from preimmunized B6 wt or TNF−/−animals were incubated for 96 hours in quadruplicate wells in the presence of allogeneic (C3HxB6) irradiated splenocytes as stimulators. Proliferation over the last 20 hours was measured by H-3-thymidine incorporation and is expressed as fold increase over incubation with irradiated syngeneic (B6) controls. The mean ± SE for one representative experiment (of 2 total) with 3 animals per group is shown. (C) C3HxB6 recipients of allogeneic (B6) TCD wt BM (5 × 106 cells) and wt or TNF−/− splenic T cells (2 × 106) were killed on days 7 and 14 after BMT. Total splenocytes were counted and donor T cells were determined by flow cytometry for Ly9.1 and CD3. The mean ± SE of one representative experiment (of 3 total) with 4 animals per group is shown. (D) C3HxB6 recipients were given transplants of TCD wt B6 BM and a high dose (25 × 106) of CFSE-stained wt or TNF−/− T cells. Spleens were harvested 72 hours later and multicolor flow cytometric analysis was performed. CD25 and CD 122 expression in CD8+ cells is shown. Percentages of CD25 and CD122-expressing cells are indicated. One experiment representative of 2 separate experiments is shown.

Percentage of IFN- γ expressing wt and TNF−/− activated T cells in response to allo- or syngeneic stimulation (percentage positive for isotype control in parentheses)

| 2° stimulation . | wt T cells . | TNF−/− T cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allo . | Syn . | Allo . | Syn . | |

| CD4+/CD62L−/CD44+ | 3.5 (0.27) | 2.2 (0.34) | 5.8 (0.34) | 1.3 (0.41) |

| CD8+/CD122+/CD44+ | 7.0 (ND) | 2.4 (ND) | 9.7 (ND) | 2.0 (ND) |

| 2° stimulation . | wt T cells . | TNF−/− T cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allo . | Syn . | Allo . | Syn . | |

| CD4+/CD62L−/CD44+ | 3.5 (0.27) | 2.2 (0.34) | 5.8 (0.34) | 1.3 (0.41) |

| CD8+/CD122+/CD44+ | 7.0 (ND) | 2.4 (ND) | 9.7 (ND) | 2.0 (ND) |

ND indicates not done.

TNF and IFN- γ serum levels in murine BMT recipients, pg/mL ± SE

| . | BM only . | +wt allogeneic T cells . | +TNF−/− allogeneic T cells . | BM + wt syngeneic T cells . | BM + TNF−/− syngeneic T cells . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | |||||

| Day 7 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 |

| Day 14 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 |

| IFN-γ | |||||

| Day 7 | < 10 | 5512 ± 1583 | 7681 ± 552 | 356 ± 304 | 389 ± 287 |

| Day 14 | < 10 | 429 ± 87 | 466 ± 120 | ND | ND |

| . | BM only . | +wt allogeneic T cells . | +TNF−/− allogeneic T cells . | BM + wt syngeneic T cells . | BM + TNF−/− syngeneic T cells . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | |||||

| Day 7 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 |

| Day 14 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 | < 50 |

| IFN-γ | |||||

| Day 7 | < 10 | 5512 ± 1583 | 7681 ± 552 | 356 ± 304 | 389 ± 287 |

| Day 14 | < 10 | 429 ± 87 | 466 ± 120 | ND | ND |

ND indicates not done.

B6 splenocytes of wt or TNF−/− origin (pooled from 4 animals per group) were coincubated in a primary MLR with irradiated allogeneic (C3HxB6) stimulator cells for 5 days, then harvested, and restimulated for 15 hours with allogeneic or syngeneic irradiated stimulator cells (T-cell depleted, to reduce contamination with cytokine-expressing stimulator cells) in the presence of Brefeldin A. All cells (“allo” and “syn”) are initially stimulated with allogeneic stimulators for 5 days for technical reasons (syngeneic “stimulation” does not yield viable cells after 5 days). Only for overnight restimulation on day 5 are responder cells divided into allo- or syngeneic secondary stimulation in the presence of Brefeldin A. This explains the small remaining fraction of IFN-γ–expressing cells in the syngeneic control group. Data from one experiment representative of 4 separate experiments are shown.

On day 0, lethally irradiated C3HxB6 mice received 5 × 106 TCD BM cells with or without the addition of 2 × 106 T cells as indicated. Serum was obtained by cardiac bleed on days 7 and 14 after BMT from 3 or 4 animals per group, and ELISA for TNF and IFN-γ was performed in duplicate for each sample. Mean (± SE in parentheses) for one experiment representative of 3 total experiments is shown.

No significant differences between wt and TNF−/− T cells were observed. This confirms the original observations of Marino et al,13 who had reported a normal MLR in CD4 cells and normal antigen-induced cytokines in TNF−/− T cells. Taken together, these results largely exclude intrinsic defects in TNF−/− T cells (other than their inability to synthesize TNF) as a cause for their decreased ability to cause GVHD and to exert a GVL effect. In an attempt to further define the level of action of TNF in these processes, we measured serum TNF levels in recipients of allogeneic BMT (Table 2). Although TNF serum levels in some murine strain combinations17,20 and in some human studies27 have been found to be high after BMT (and predictive of GVHD), we have—with 2 different assays—not been able to find measurable TNF serum levels in any of our experimental groups (Table 2) (whereas TNF standards gave us expected levels of TNF, and IFN-γ serum levels were in the expected range). Serum cytokine levels are known to be dependent on conditioning regimen, time after transplantation, and strain combinations. Elevated serum TNF in murine BMT was detected by other groups17,20 using identical conditioning regimen and time points, but not the same strain combination, which might account for the variant outcome. Nonetheless, our results indicate that at least in our model, T cell–derived TNF contributes to GVHD and GVL locally and not via systemic levels. Future studies with recently developed TNF knock-out/membrane-bound TNF knock-in mice28 might be able to differentiate whether this action occurs via paracrine secreted TNF or via membrane-bound TNF on the T cell.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate for the first time a critical role for donor T cell–derived TNF in 2 core phenomena of the pathophysiology of BMT: it contributes to GVHD and GVL effect via a local pathway. Although previous data have indicated a role for TNF in GVHD and GVL, the demonstration of the donor T cell as a novel and highly relevant source of TNF and the evidence that its effect does not depend on serum level, but rather functions in a paracrine mode or as a membrane-bound molecule in T cell–target interactions contributes to the further delineation of the mechanism of GVHD and GVL and opens a field for further studies. This is particularly timely as the new TNF antagonists Etanercept and Infliximab are currently in clinical trials for the treatment of human GVHD and early positive results have been reported.29

We wish to thank Dr Michael Marino for TNF−/− mice; Dr Malcolm Moore, Dr Keith Elkon, and Dr Richard O'Reilly for helpful discussions; the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Research Animal Resource Center for skillful animal handling; and Dr Hai Nguyen for histopathological examination of tissue specimens. Jennifer Ongchin, Jeff Eng, Kartono Tjoe, Margot Campbell, and Alice Oliveira provided excellent technical assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 7, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2109.

Supported by grants HL69929 and HL72412 from the National Institutes of Health (M.R.M.v.d.B.), a Special Fellowship of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (C.S.), a Damon Runyon Scholar Award of the Cancer Research Fund, a scholarship of the V Foundation, and an award of the Wendy Will Case Cancer Fund (M.R.M.v.d.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Marcel R. M. van den Brink, Department of Medicine, Box 111, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York NY 10021; e-mail:m-van-den-brink@ski.mskcc.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal